Bugs: The secret history

Wednesday | January 7, 2009 open printable version

open printable version

DB here:

One of the many penalties of watching movies on TV is the prevalence of bugs.

This is the nickname adopted by media makers for those little channel logos and watermarks that hop onto your screen. Sometimes these translucent signatures surface at intervals, to minimally satisfy FCC channel identification demands. Others let you know the movie you’re watching, or will be later.

But just as often the bugs just squat in a corner forever, teasing your eye away from the movie. Bugs are to the 2000s what editing and time-compressing were to earlier eras. “Movies, uncut,” boasts the IFC bug. But not unspoiled.

Bugs are bad enough when they are hovering in a black vacuum, made forlorn by letterboxing.

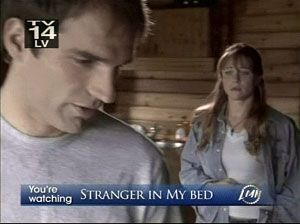

But they really jump into competition when they take up part of the image. How can you watch what actors are doing when there’s something faintly readable floating up from below?

I find it impossible not to look at a bug occasionally. In dark shots, sometimes it’s the most visible thing on the screen. Even in bright shots I stare at it. Maybe I’m hoping that it will be different this time. Yet when it changes, as it does on the Lifetime channel, I watch it more attentively, which only makes me more annoyed.

It’s like the mesmeric spell of Time Code, ticking away the movie’s life, and yours.

I’m not the first to complain. An eloquent manifesto, originally called Squash the Bugs, dates back to 2000, when the infestation was starting. Several other souls participated in the movement.

We know why bugs are swarming all over TV. Somebody better dressed than you or me is worried that we will be recording A Christmas Story or Smokey and the Bandit or Stranger in My Bed. We might even try to sell copies, or post a clip online. In principle, the bug is a badge of ownership, warning that we could be prosecuted. In practice, nobody expects to sue every user, so bugs help spread the brand. It’s like putting a designer logo on a shirt, making you a walking ad. Who wouldn’t want their bug, microscopic as it is, all over YouTube (which of course tacks on its own bug)?

But like everything else that we take for granted, bugs aren’t new. In their earlier form, they’re rather likable.

Silent but deadly

Movie bugs go back to the first years of cinema, when producers were no less worried about media piracy than they are today. Between 1895 and 1915, films circulated very freely around the world, and enterprising crooks happily duped originals and passed them off as their own productions. To block this, filmmakers tried to find ways to keep their trademarks on the film.

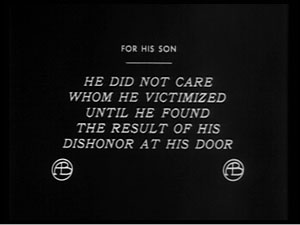

The obvious step was to put the trademark in the intertitles, and many companies did. Here is one for For His Son, a 1912 Griffith film from American Biograph. (What did the protagonist do for his son? He created a soft drink called Dopocoke, which turns the college boy into a hopeless addict.) Note the handsome AB insignia.

But of course a pirate could simply replace such original titles with ones of his own. The next logical step was to incorporate the trademark into the images, which couldn’t be replaced. Without the technology to create near-invisible superimpositions, the filmmakers took the obvious course.

They put the company logo into the set.

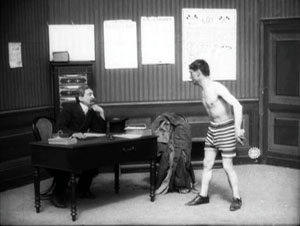

The AB circle typically appeared as a wall decoration. Biograph characters loved to furnish their surroundings to highlight this motif, preferring to put it at eye level and frame center. The logo could be found in unexpected places, like movie theatres (Those Awful Hats, 1908), and it could brighten the dreariest hovel (What Shall We Do with Our Old?, 1911).

The plaque’s popularity stretched back to Civil War days (In the Border States, 1910), and even in medieval times a king might mount the stylish AB on a brick wall (The Sealed Room, 1909).

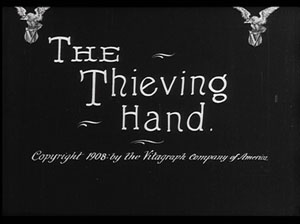

Not to be outdone, Biograph’s competitor, the Vitagraph company, had a beautiful soaring eagle logo, which conveniently furnished a striking V graphic.

Judging from the evidence of this 1908 film, however, Vitagraph had a sideline in manufacturing safes.

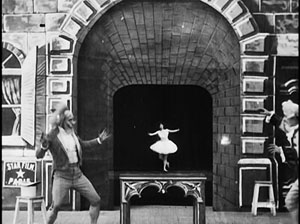

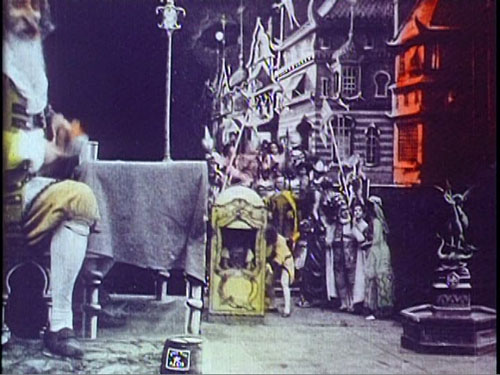

The practice of building the trademark into the mise-en-scene seems to have begun in France. Georges Méliès, whose fantasy films were popular around the world, took measures to counter piracy early. You can see his Star-Film logo on the building stone in the left corner of this frame from La Danseuse microscopique (1902). Shift it to the right corner and we’d have a modern-day bug.

At the very top of this entry is a frame from Le Voyage de Gulliver à Lilliput et chez les géants (1902). There Méliès attached the Star-Film seal to the barrel sitting just left of center.

At the very top of this entry is a frame from Le Voyage de Gulliver à Lilliput et chez les géants (1902). There Méliès attached the Star-Film seal to the barrel sitting just left of center.

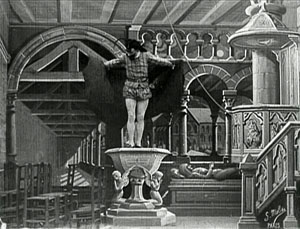

But Méliès didn’t always shove his imprimatur to the edge of the frame. In Le Tonnerre de Jupiter (1903) it sits just below the eagle that Zeus bestrides.

In the earlier Diable au convent (1899), Méliès exercised another option, simply signing his image as if it were a painting. To a large extent, it was.

Léon Gaumont had two marques, each enclosed in a chrysanthemum ring. The most famous one is a majestic Gaumont, but an alternative, ELGE (that is, LG), haunts Alice Guy’s Billet de banque (1907). First, in a café, the logo is attached to a table, and later it’s a decorative baseboard in a police station.

In Guy’s Le Frotteur (1907), Gaumont simiply stuck its logo to a chair leg.

Then there’s the Pathé Frères rooster.

Easy enough to embed that, you’d think. Just have a rooster stroll through a shot now and then—not only barnyard scenes, but ones set in a courtroom or a factory. Still, roosters are pretty accessible to any film pirate, so Pathé went the more ordinary route of weaving its logo into the set.

An insistent example comes in The Physician of the Castle (1907), possibly the source for Griffith’s The Lonely Villa (1908) and Lois Weber/ Phillips Smalley’s Suspense (1913). The plot is sort of a 1907 Panic Room. The logo is initially a plaque in the parlor of the castle, visible just behind the kneeling doctor.

An identical plaque is perched in nearly the same spot on the wall of the doctor’s own parlor, as we can tell when his family is besieged by the invading tramps.

The tramps pass through another room, where the trademark stands proudly on another wall, on screen right.

And when the wife tries to phone the husband for help, we get an insert that shows the Pathé cock nearly perched on her shoulder.

Why do I find the old bugs charming and the new ones annoying? I suppose it’s partly because the old ones were hand-crafted, not the result of keyboard twiddling. They are tangible. They are part of the scene’s space. Hard to see on DVD, the embedded marques are striking in 35mm projection, and spotting them is part of the pleasure of early film. Moreover, the filmmakers intended them to be there, or at least they accepted the need for them. But what director today is happy when the Sundance bug creeps into her compositions?

The old bugs seem to have gone extinct around 1912, but they will cling to their films. They bear witness to filmmaking of a specific time, and they anticipate problems that persist today. In tackling the threat of piracy, the old bugs seem at once naïve and intelligent. I see them as a rational solution to a hard problem, narrative consistency be damned. Today’s bugs, floating on top of the story world, seem more like corporate tattoos or graffiti. They don’t exist within the action, so you could argue that they are less disruptive. But they become a different sort of distraction, hovering halfway between the story world and the space of viewing. Bugs are spectres haunting the film.

On rare occasions, a modern add-on can be appropriate. In a Méliès film on the recent Flicker Alley set, L’Oracle de Delphes (1903), some TV agency has clapped its own digital bug into the lower right corner. It really is about beetle-size, and it dares to be a single eye looking back at you. That icon adds a touch of peculiarity not out of keeping with the Méliès aesthetic.

You can argue that this smirch on the image is a minor sacrilege. But I suspect that the Master of Montreuil would have grinned in approval.

For more on bugs, aka DOGS (Digital Onscreen Graphics), see Wikipedia. Thanks to Jason Mittell for helping me name these pests. And all hail Turner Classic Movies for keeping its bugs to a minimum.

The Sunbeam (Griffith, American Biograph, 1912).

PS 19 January 2009: “Subliminal” bugs: I had hoped to include a frame illustrating the anti-piracy stamp used on current 35mm releases, but couldn’t find one quickly. This mark consists of a tight pattern of dots resembling a character in Braille. The stamp would presumably be copied if someone shot off the screen or ran the film through a telecine. How effective these bugs are at tracing pirate copies I can’t say, but you can detect them, especially in bright scenes; I usually notice one every third reel or so, just left of the center of the frame. I’ll keep looking for a frame and try to add one to this entry.

John Powers alerted me to the fact that even Michael Snow’s Région Centrale got the bug treatment when it was telecast on Italy’s RAI 3 TV. Thanks to John for this scary example.

P.P.S. 24 January 2009: On the Internets, ask and ye shall receive. Olli Sulopuisto wrote to link me to the Wikipedia entry explaining the domino dots, known as CAPs. The entry includes an illustration. Olli also contributed to Jim Emerson‘s scanners blog, which contains good commentary on CAPs from Jim and his readers.

P.P.P.S. 29 May 2013: Can anti-piracy bugs be integrated into the movie or TV show? Yes!