Acting up

Thursday | February 26, 2009 open printable version

open printable version

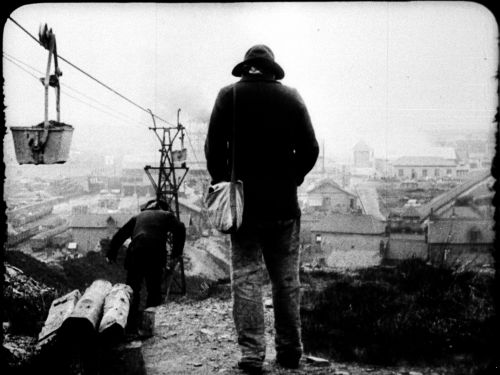

Germinal (1913).

DB here:

Film performance is notoriously difficult to analyze. We don’t lack zesty celebrations of actors; I think especially of Richard Schickel on Doug Fairbanks and Gary Giddins on Jack Benny and Bob Hope (praised in an earlier entry). But we have long found it difficult to penetrate actors’ secrets with the same precision that we bring to editing or framing or a film’s musical score.

Actors’ performances don’t offer themselves in neat slices, the way that shots come to us. There isn’t a firm notational system that lets us capture performances the way that scores can pick out important patterns in music.

Moreover, it’s hard to dissect something that seems so evanescent, so direct, and so natural. When we see someone smile on the bus or at a party, we react immediately and without any apparent thought. When someone smiles in a movie, we’re tempted to say that we respond just as directly. But then, what is acting? Just doing what comes naturally?

Acting is clearly an art and a craft. Not everyone can do it, and comparatively few do it well. So if there is a skill or a technique involved, surely acting goes beyond ordinary behavior. And if as in other arts there are creative choices involved, there is likely to be a menu of options to be chosen from. Some of those options are likely to be conventions sanctioned by tradition. How strongly, then, is acting conventionalized? If it’s conventionalized to some degree, we should be able to analyze it.

A small-scale debate has gone on for some years in film studies about whether film acting is heavily conventionalized, even coded. Advocates of the coding view point to the fact that acting styles vary in different places and change across time. What does Kabuki performance have in common with Method acting? It’s hard to claim that there is a universally realistic acting style that naturally represents human behavior. Against this, others have argued that even if there is no absolute and unchanging standard of realism, we can speak of more or less realistic aspects of performance. Some styles, like Method are just less artificial than others, like Kabuki—even if both are somewhat stylized with respect to realistic behavior.

My own view, explored in Poetics of Cinema, is that performance traditions streamline or stylize a common core of widely shared human behaviors. In everyday life, smiling expresses happiness and/or serves as a social signal of openness. We’re unlikely to find a distant culture in which smiling expresses rage. (Of course we can have an instance of smiling concealing rage, but that would acknowledge the difference between the two states.) Some acting traditions, like Kabuki, retain certain common behaviors like weeping or proud walking, but make them more dancelike. Other acting traditions stylize core behaviors in different ways–the mumble of the Method, or the comic double-take. The differences lie in what aspects of facial expressions, gestures, gait, and the like are on the tradition’s menu, and how they become “streamlined” for expressive purposes and spectatorial uptake.

In short, I’m a moderate constructivist about such matters. I agree that we have to learn to comprehend performances in different traditions. But our learning is fast and spontaneous, not at all like learning Morse code or English, because we already have strong hunches about what a frown or a wail might express. Frowning or wailing are likely to be contingent universals of human behavior. An intuition about the meaning of the performance guides us to recognize the more stylized aspects of the presentation. When Cesare coasts along walls in The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, we take that to be a stylized representation of the act of stalking. That construal relies on the hunch that he’s doing something we already understand–stalking–in an unusual way. Although sometimes we might have to revise our intuitions about the meaning, those intuitions serve as a point of departure. (Where do our intuitions ultimately come from? Short answer: The evolution of humans as a social species.) E. H. Gombrich put it well: “It is the meaning which leads us to the convention and not the convention which leads us to the meaning.”

Assunta Spina (1915).

The faculty and alumni of the Film Studies program here at Wisconsin keep in touch through a (closed) listserv, and thanks to Jonathan Frome we also have a wiki, to be found here. It’s just starting to fill up, mostly with ideas for teaching and examples of sample sequences to illustrate film techniques. But now the wiki has gained striking essays on acting from two scholars of early cinema.

Ben Brewster and Lea Jacobs’ book, Theatre to Cinema, took on the problem of what early feature films owed to the stage, and they concluded: Quite a lot. But instead of condemning this tradition as “uncinematic,” as most historians have, they showed that a highly engaging form of cinema arose by reshaping theatrical traditions. Specifically, Ben and Lea examined how “situational” plotting principles were carried into film, and they discussed film’s debt to the “pictorialist” drama of the nineteenth century. Many scholars had argued that melodramatic theatre was replaced by the Naturalist theatre, derived from the literary movement associated with Émile Zola. But Lea and Ben argued that a pictorialist conception of theatre and its modified form in early feature films cut across this distinction. A film that was avowedly Naturalist in plot or theme could maintain conventions of earlier forms.

Consequently, they argued that film acting of the period, even when it seemed to be moving toward greater realism, was still building on the stereotyped expressions, gestures, and attitudes of pictorialist theatre. Actors were called upon to execute vivid stage tableaus. Standard gestures had to be imbued with fresh emotional intensity, and actors were expected to move gracefully from one expressive picture to another.

Now Ben and Lea have extended their book’s argument in two in-depth studies posted on the UW wiki. Ben’s essay examines that great Capellani film Germinal (1913) and shows that it often perpetuates the poses and expressions of pictorialism, while also scaling them down. Lea tackles the work of the diva Francesca Bertini, including an analysis of the wonderful Assunta Spina (1915). Her piece is a companion to Ben’s. She writes:

While I do not doubt that the plot of Assunta Spina fits under the rubric of naturalism, and that the acting and staging of some scenes in the film also show the influence of naturalism in the theatre, it seems to me that Bertini’s technique (and incidentally that of [Asta] Nielsen as well) is more reminiscent of Bernhardt than it is of the Duse, and that the blocking and use of gesture in the film is largely governed by what Brewster and I have discussed in terms of “pictorialism” in acting.

By considering 1910s performance as a modification of theatrical poses, attitudes, and staging conventions, Jacobs and Brewster are led to remarkably detailed analyses. They have studied the conventions of acting at that period, and because they are alert to standard bits of business, so they are able to show fine points of performance that we would ordinarily miss.

They’re also able to hold the realism/ artifice dispute in suspension by concentrating on particular historical traditions. They shrewdly note that as acting styles change, the newer one is likely to be praised as more realistic than the styles it supplants. In turn, that style will be considered artificial when a still newer one comes along. For this reason, Method acting may seem less realistic and more artfully contrived today than it did in the 1950s.

Apart from the subtle discussion of acting styles, one merit of these essays is that they recognize how films can take bits and pieces of different traditions and modify them for particular ends. I’m sympathetic to this perspective. For instance, I still think that many of today’s Hollywood films, despite their contemporary look and feel, draw on principles of narration and plot structure that we can find in classic American studio cinema.

In addition, you ought to visit the site to see how detailed their analyses are and how extensively they draw on frame stills. Indeed, one reason they published these pieces online was that no academic film journal could have accommodated so many illustrations. So much the better for us. The frames, taken from 35mm prints with a Nikon lens and negative film, are among the most beautiful you’ll find on the Internets. I swiped some here.

Sangue bleu (1914).

The quotation from E. H. Gombrich comes from his essay “Image and Code: Scope and Limits of Conventionalism in Pictorial Representation,” in The Image and the Eye: Further Studies in the Psychology of Pictorial Representation (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1982), 289.

Kristin has written a couple of blog entries concentrating on performance, here and here.