Beyond praise 2: More DVD supplements that really tell you something

Thursday | March 26, 2009 open printable version

open printable version

Kristin here-

In September of 2007 I posted the first “Beyond praise” entry, the idea being that I would recommends DVD supplements that didn’t just contain a lot of participants in the filmmaking process gushing about how wonderful their colleagues were. Such supplements would reveal something about the filmmaking process, and perhaps something about the publicizing and exhibition as well.

I intended to make this a regular feature of the blog, so it’s high time to post a follow-up entry. These comments don’t necessarily deal with very recent releases. Some are a few years old by now. Still, I’ve just caught up with them, and they haven’t lost their interest for film buffs, teachers, and students.

Collateral (“Two-disc Special Edition,” DreamWorks Video)

The making-of, “City of Night: The Making of Collateral,” is short by current standards, at about 39 minutes. It’s dense with information, though. Indeed, David and I were inspired by it, along with the account of the film’s making in American Cinematographer, to add a case study on the film’s production to Film Art. The 9th edition, coming in December, will start with this case study and how the aesthetic decisions made by the filmmakers affected the final film. (One of the book’s users suggested this idea, and we think the result improves the opening chapter.)

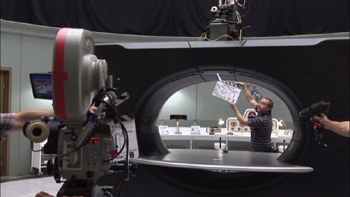

Michael Mann wanted to capture the unique glow of Los Angeles at night, caused by the bright lights of its flat grid being reflected by the atmosphere over the city. To do so, he employed digital cameras for most scenes. The documentary shows how the cameras allowed filming almost entirely with ambient light. (See illustration below.) Fill light was added subtly by innovative flexible panels Velcro-ed onto the interior of the cab that forms a major setting for the action. One suspenseful scene near the end was filmed in a darkened office, with the actors becoming completely black silhouettes against the lights of the city outside the windows. For those who may not be familiar with professional-level digital filming, this making-of offers a succinct introduction. Collateral remains one of the best films shot primarily with digital cameras, and it makes a good case for the new technology for those who may doubt that it can ever be as effective as 35mm film.

“City of Night” also has the best demonstration I’ve seen of the use of multiple cameras to shoot a big action scene, detailing how the spectacular taxi crash was planned and executed. (But see also the 3:10 to Yuma description below.) There’s an interesting segment on the music, where composer James Newton Howard talks about composing the music for the extended climactic chase in “three movements.”

There’re also some rehearsal footage and other minor supplements, but the main documentary is far and away the most informative. It could be quite useful for teaching cinematography.

Hellboy (“2-Disc Special Edition,” Columbia Tristar Home Entertainment) and Hellboy II: The Golden Army (“3-Disc Special Edition,” Universal Studios Home Entertainment)

Guillermo del Toro being the geeky fanboy that he is, the supplements for the two Hellboy films are lengthy and full of solid information. The first film was made on a smaller budget, as was its main making-of, “Hellboy: The Seeds of Creation.” Essentially it alternates candid footage captured on working sets, which is really more decorative than informative, with interviews and segments on specific topics. There’s a little of everything one would expect for an effects-heavy film: bits on maquettes, set models, testing of stunts, animatronic figures, and so on. Cinematographer Guillermo Navarro talks briefly about lighting tests for Hellboy, accompanied by such beautiful images as the one above, imitating the vivid, high-contrast look of the original comic.

The making-of contains nice little segments that superimpose a digital double on raw footage (at about 29:30 minutes), a good illustration of building a CG figure by adding musculature to a wire-frame base (70 min.), and a more detailed treatment of ADR than most supplements offer.

The making-of for the sequel, “Hellboy: In Service of the Demon,” is more extensive and was evidently planned  more thoroughly. One early scene has del Toro seated on the floor having a decidedly informal meeting with his design staff. It’s clearly a real, working meeting, not one staged for the camera. The director has some intelligent things to say about the monsters he wants from his team (“No aliens!”), and his voice continues over shots of the designs that the people sitting with him came up with. There’s a great deal of material on the design and construction of the famously large number of demons, 32 in all, as well as on-set demonstrations of how the elaborate costumes are worked by the actors inside them and by remote control.

more thoroughly. One early scene has del Toro seated on the floor having a decidedly informal meeting with his design staff. It’s clearly a real, working meeting, not one staged for the camera. The director has some intelligent things to say about the monsters he wants from his team (“No aliens!”), and his voice continues over shots of the designs that the people sitting with him came up with. There’s a great deal of material on the design and construction of the famously large number of demons, 32 in all, as well as on-set demonstrations of how the elaborate costumes are worked by the actors inside them and by remote control.

Highlights: a good explanation of how points of control are added to CGI creatures and function to create the final image; another on how motion-control is used for special effects; a view of a video-assist playback. Particularly impressive is the lengthy scene in which we watch the make-up for the Angel of Death being designed and applied while actor Doug Jones talks intelligently about the make-up and the character.

The supplement is long, about two and a half hours, but I think I’d choose it, or at least big portions of it, if I wanted to teach about special effects to an introductory class. Like Peter Jackson, GDT is a big advocate of using practical effects whenever possible and resorting to CGI only when they aren’t possible. As a result, this making-of demonstrates an unusually wide range of kinds of effects. It’s also entertaining, clear, and has interviews with most of the principals involved in each kind of task.

3:10 to Yuma (Lionsgate)

The supplements for James Mangold’s Western (the sound mixing of which David blogged about here) are less lavish but still of interest. There’s a section on how the four major sets were constructed on location rather than in sound stages. One detailed segment shows a camera rig for moving with a stagecoach and the practical special effects used for the scene in which the coach is  flipped over. I learned, for example, that “crash cam” is the name for the metal cylinder used for the camera most likely to get hit by the flipping vehicle-a device also on view in the Collateral supplements. The crash scene is particularly well done, showing the shooting with multiple cameras and then immediately the crash as edited.

flipped over. I learned, for example, that “crash cam” is the name for the metal cylinder used for the camera most likely to get hit by the flipping vehicle-a device also on view in the Collateral supplements. The crash scene is particularly well done, showing the shooting with multiple cameras and then immediately the crash as edited.

There are bits of out-of-the-way but fascinating information here. For example, there are companies that rent old trains for film production. There are also guns that shoot dust capsules (left) into the set to simulate bullet impacts and other bits of flying debris. Apart from the main documentary, there’s a six-minute segment, “An Epic Explored,” where Mangold talks about making a Western in a period when the genre is out of fashion, and a brief history of “Outlaws, Gangs and Posses” that could be useful for background information on Westerns in general.

The Golden Compass (“New Line 2-Disc Platinum Series,” New Line Home Entertainment)

I was interested in The Golden Compass from its inception, since it was New Line’s intended replacement for The Lord of the Rings as the studio’s prestige franchise. That didn’t work, of course. (I wrote about how New Line copied its Rings strategies in promoting The Golden Compass here and about why the film succeeded abroad but not in the U.S. here.)

As an admirer of Philip Pullman’s His Dark Materials trilogy, I was also curious about how well the lengthy, complicated first novel could be adapted for the screen. My impression upon seeing the film was that the first half raced along, presenting essentially a brief summary of each scene and trying to cram in exposition about the huge number of characters and plot points retained from the novel. The second half calmed down and was more successful in its rendering of events.

The Golden Compass was a failure from New Line’s point of view-and that of parent company Time Warner, which used that failure as an excuse to fold the semi-independent studio into Warner Bros. It made about $372 million internationally, but the overseas take was $302 million of that total. That money stayed with the foreign distributors, who had helped finance the film through pre-sales of rights. That and its reported $180 million budget meant that New Line lost a bundle.

The DVD supplements reflect nothing of these problems. They’re distinctly better than the lackluster titles of the individual segments suggest. There’s a nice section on the novel, with Pullman saying some interesting things. “The Adaptation” mostly depends on interviews with director Chris Weitz and producer Mark Ordesky. Throughout the supplements, Weitz, who was relatively inexperienced when he took on the epic production, is not only modest but downright self-deprecating-sort of the opposite of too much praise. (“The fact of the matter is that there have been hundreds of people working on this just as hard as I have, and this is not the kind of film that really fits in with a kind of an auteur theory of filmmaking.”) Perhaps the director will feel more confident on his next project, the sequel to Twilight.

The makers of the supplements chose an effective tactic of choosing one major item in each category to concentrate on, rather than trying to cover every aspect of casting, design, and so on.

“Finding Lyra Belaqua” seemed to promise the usual uninformative gushing about how wonderful Dakota Blue Richards was in the lead role. In fact it’s quite an interesting account of how open casting calls work. The casting team have calls in multiple towns, where enthusiastic little girls in the queues explain their fascination with the project. The casting of Richards must have become pretty likely at some point, since the documentarists followed the young actress and her mother through a string of call-backs and the tense process of whittling the short-list down.

The “Daemons” section spends minimal time on explaining the concepts and instead concentrates on the design, the creation of maquettes for CGI work, and the necessary but rather silly use of stuffed animals on the set to stand in for the daemons. The section on how Freddie Highmore had to dub in Pantalaimon’s dialogue in ADR while watching unrendered computer images of his character is particularly interesting.

Again, a fairly lengthy session devoted to the design and making of “The Alethiometer” (15 minutes on a single prop) is not simply devoted to explaining what it is. Instead, it gives a real sense of the elaborate process of seeking real-world models, finding experts create for each type of part needed, and making the prototype. The section on production design focuses on the use of conflicting shapes as motifs throughout the film: circles for Oxford, Lyra, and the Alethiometer, ovals for Mrs. Coulter and the Magisterium. These show up in vehicles, sets, and props:

Other segments are similarly clever and informative: on how costumes affected the way the actors had to walk; on the steps used to create the entirely CGI-based armored-bear battle; on the music’s use of exotic instruments to characterize the various imaginary ethnic groups. There’s even a segment on the Cannes press-junket launch, with a brief interview with a junket producer-something I certainly haven’t seen in a supplement before.

I had hoped to be able to recommend the supplements for Across the Universe. Julie Taymor’s musical is so imaginative and appealing that one would expect some clever and original making-ofs as well. Unfortunately most of the five brief documentaries fall into the mutual-praise trap (“Everyone wants to work with her!”). “Stars of Tomorrow” is 27 minutes of guff about how the young actors were cast and how wonderfully they fit their roles. “Moving across the Universe,” on the choreography, is pretty good-but only 9 minutes long. The best things in the supplements are the clips from the film. Watch it, skip the extras.