Jackhammers, parties, and markets

Sunday | March 29, 2009 open printable version

open printable version

DB here:

No matter how often you see this Ur-touristic view, it’s still spellbinding. Yes, I’m back at the Fragrant Harbor for the annual festival, front-loaded with Filmart, the film market. My 2008 report starts here, and the 2007 one starts here. Plenty of entries for those years; I’m not sure I’ll be able to roll out so many this time, but we’ll see.

Start with the first impressions. Massive building projects and new traffic-flow strategies have made the tip of the Kowloon peninsula even more pedestrian-unfriendly than last year. Grim underground passages take you in loops away from your destination. No more direct routes anywhere, it seems, and construction projects I’ve watched for years continue to be unfinished. From the twenty-first story of my hotel I can hear a jackhammer at street level.

A striking case: My hotel is rather close to a multiplex in West Kowloon, located in an upscale mall called Elements. (More on Elements in a later communiqué.) But around this trendy spot stretches a vast vacant lot.

Again, there’s a lot of pedestrian control, including barriers to keep you from crossing the street. Still, it’s not hard to find places where enterprising passersby, perhaps armed with blades, have broken on through to the other side.

Moreover, the Star Ferry to Wanchai still offers a pleasantly sustained ride and the usual spectacular views, even in the rain and mist that have enveloped my first days here.

Wanchai is the location of Filmart, set up in the Convention Centre, the mammoth swooping building seen at the top and bottom of this entry. As usual, Filmart was stuffed with seminars, screenings, and dealmaking, as well as the Asian Film Awards.

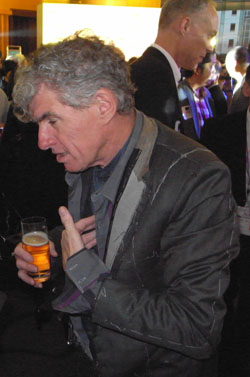

The opening of Filmart included a party, where you could find Chris Doyle, accompanied by a beer, rubbing shoulders with Stefan Borsos, editor of the German magazine CineAsia.

The party got stranger. This year’s festival logo is a dude in black tie with a black starburst head and a hollow look around the eyes. I thought he was only a graphic design until Karen Mok brought him onstage.

He seems a saucy fellow, at least judging from his hand gesture here.

Filmart opened with a screening of Derek Yee‘s new film Shinjuku Incident. Before the show, Yee, on left, lined up with his cast. You can recognize at least one of the ensemble, grinning as usual.

In the following days, I saw several good movies: More on them in the next post in a day or so. I also attended some sessions devoted to technology and marketing. The effects company Digital Magic sponsored a demonstration of various digital formats, of which the Red system seemed to me the best. Digital Magic also gave out cute Viewmaster-like toys promoting their work.

I learned things from this session and the one sponsored by Salon Films, but the main live event I hit was the Hong Kong Film New Action Forum, a day-long series of sessions about the future of Chinese film. The first item was a brief discussion moderated by director Gordon Chan (Beast Cop, Painted Skin; left). Two experts discussed the current status of CEPA, the Closer Economic Partnership Arrangement that allows Hong Kong productions to count as mainland ones for purposes of financing and distribution. Across the last few years, half or more of the top-grossing pictures, such as the Zhang Yimou costume epics and Peter Chan’s Warlords, have been CEPA-enabled coproductions. Other countries, such as Singapore, Japan, and Korea, are investing in such projects.

I learned things from this session and the one sponsored by Salon Films, but the main live event I hit was the Hong Kong Film New Action Forum, a day-long series of sessions about the future of Chinese film. The first item was a brief discussion moderated by director Gordon Chan (Beast Cop, Painted Skin; left). Two experts discussed the current status of CEPA, the Closer Economic Partnership Arrangement that allows Hong Kong productions to count as mainland ones for purposes of financing and distribution. Across the last few years, half or more of the top-grossing pictures, such as the Zhang Yimou costume epics and Peter Chan’s Warlords, have been CEPA-enabled coproductions. Other countries, such as Singapore, Japan, and Korea, are investing in such projects.

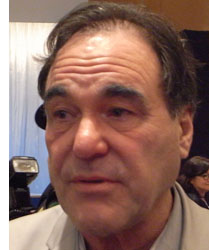

The other session I attended was more high-profile. Philip Chan, screenwriter and former cop, moderated a discussion among John Woo, Oliver Stone, Andrew Lau Wai-keung, and Feng Xiaogang. The Chinese directors talked about the market. Stone talked about creativity. This division of labor reminded me of what Bernard Shaw supposedly told a Hollywood producer: “The problem is that you are only interested in art, and I am only interested in money.”

Woo took the floor with a long discussion of making Red Cliff. He made the usual point about wanting to wed Chinese stories to Hollywood production values. Some other items:

Woo took the floor with a long discussion of making Red Cliff. He made the usual point about wanting to wed Chinese stories to Hollywood production values. Some other items:

*He built the project to have marketing appeal, designed both for Asian and western consumption. For instance, strong women appeal to female viewers in all countries. He claimed that one reason that Red Cliff broke attendance records in Japan was the support of women audiences.

*Woo also wanted to bring audiences in Hong Kong and China back to local films, away from Hollywood imports. Viewers, he claims, are bored with Hollywood’s formulas and want something fresh and authentic. But local audiences are getting tired of Chinese blockbusters too, so in Red Cliff Woo introduced humor along with Hollywood-level production values.

*He suggested that before making Red Cliff he had considered retiring. Now he’s planning more projects.

Lau and Feng likewise took up practical considerations. Lau said that filmmakers must go where the market leads. He suggested there was a period when Hong Kong filmmakers went to Hollywood, but now that route is risky. At the moment, the market is the Mainland, not the West. He was not rueful about his own experience in Hollywood (with The Flock), but he treated it as a chance to learn “a different set of rules. Every place has its own rules.” He also spoke of the unexpected success of Infernal Affairs, a “back-to-the-wall” effort that seemed risky in the market decline of the 2000s. No one expected the film to be so successful; the actors cut their asking prices to be in it.

Feng Xiaogang, Mainland director of Cell Phone and A World without Thieves, lived up to his reputation for stirring things up. Announcing that Hong Kong people “consider the Mainland a four-letter word,” he rattled off an account of the current PRC market. Feng indicated that a $20 million film can presently break even in the domestic market. This prospect interested me, because such benefits are rare in the history of movies. As film students know, the US used its big domestic market as a base to launch vast overseas distribution.

Box-office income is growing fast, but there aren’t enough screens. He claimed that there were about 4000 in the country, an absurdly small number for such a populous country. (Probably this figure counts only modern screens, not old or temporary ones.) The key, Feng suggested, was capitalizing the building of still more screens, especially in the 350 “small” cities. The government will subsidize theatre construction to some extent.

If 1000 more screens are added, Feng speculated that in five years the annual box-office receipts could hit 30 billion RMB. That’s about $4.5 billion, somewhat less than half of the 2007 US box-office take—but twice as much as the income in Japan for the same year. China is developing into a prepossessing market.

Finally, Oliver Stone confessed his love of Asian films, singling out their “iconic imagery” (Crouching Tiger, even Woo’s Face/Off) and lyricism (Ozu, Wong Kar-wai). His advice: Don’t withdraw from engagement with the West and “Make films that pop their eyeballs out.”

Finally, Oliver Stone confessed his love of Asian films, singling out their “iconic imagery” (Crouching Tiger, even Woo’s Face/Off) and lyricism (Ozu, Wong Kar-wai). His advice: Don’t withdraw from engagement with the West and “Make films that pop their eyeballs out.”

One theme I took away was the way in which regionalism continues to rule the Asian industries, a topic I raised in Planet Hong Kong and in late chapters of Film History: An Introduction. Who needs Western markets if the PRC market continues to swell and if other territories in the area hold up their end of financing, distribution, and the occasional regional hit? As far as mass-market cinema is concerned, we may be moving toward a bipolar world, with North America at one pole and Asia at the other. For an excellent, fact-filled analysis of the implications of this trend toward regionalism, see Darrell William Davis and Emilie Yueh-yu Yeh’s brand-new study, East Asian Screen Industries.

Soon, very soon, we go to the movies.

Screen Digest offers some slightly older statistics on the Mainland market here. For more recent information on Chinese exhibition in a worldwide context, see “Exhibition Breaks Revenue Record,” Screen Digest (September 2008), 274. The number of screens cited here is far greater, perhaps because it counts all the rural, unmodernized, or temporary venues. Karen Chu of the Hollywood Reporter sums up the New Action Forum event here.

Hong Kong Convention Centre.