Confucius reborn

Wednesday | April 15, 2009 open printable version

open printable version

DB, in Hong Kong:

Fei Mu is a little-known name in the West, but on the evidence of even a few films, it’s clear that this mainland Chinese filmmaker was one of the finest working anywhere during the 1930s and 1940s. His best-known film, Spring in a Small Town (1948), was considered in the Maoist era an overliterary piece of sympathy for the bourgeoisie. Now things have changed. Many specialists today consider Spring in a Small Town the best Chinese film of all time. It’s an extraordinary work, anticipating Antonioni in its slow unfolding of an erotic situation, treated with a mixture of sympathy and austerity. It’s a great pity that the film isn’t available on good and subtitled DVD copies, though a digitally restored print was made in 2005.

Fei Mu is a little-known name in the West, but on the evidence of even a few films, it’s clear that this mainland Chinese filmmaker was one of the finest working anywhere during the 1930s and 1940s. His best-known film, Spring in a Small Town (1948), was considered in the Maoist era an overliterary piece of sympathy for the bourgeoisie. Now things have changed. Many specialists today consider Spring in a Small Town the best Chinese film of all time. It’s an extraordinary work, anticipating Antonioni in its slow unfolding of an erotic situation, treated with a mixture of sympathy and austerity. It’s a great pity that the film isn’t available on good and subtitled DVD copies, though a digitally restored print was made in 2005.

Two other Fei Mu films I’ve seen show the variety and flexibility of his craft. Onstage, Backstage (1936) is a drama of theatre life, and its fluid figure movement in depth recalls Renoir. Very different is the expressionistic allegory Nightmares in Spring Chamber (1937), an episode in the portmanteau film called Lianhua Symphony. Fei presents the Japanese invasion of China as the pursuit of an innocent girl through dark sets by a leering, frock-coated Japanese. Other surviving Fei works, such as Blood on Wolf Mountain (1936), are also held in high regard. After Mao’s revolution, Fei Mu moved to Hong Kong, where he died at the age of 45. He directed no films in the Crown Colony.

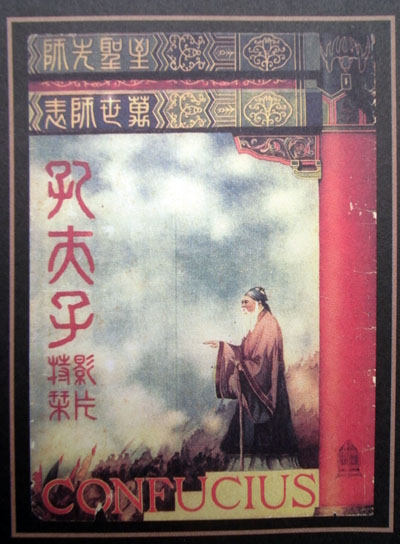

All this makes the discovery of a print of Confucius (1940) an event of capital importance. An anonymous individual donated a print to the Hong Kong Film Archive, which spent years restoring it in collaboration with L’Immagine Ritrovata of Bologna. In the donated print of Confucius, some portions of the soundtrack had liquefied, so some stretches are silent, and there are about nine minutes of fragments that have yet to be integrated.

At the premiere, a very useful booklet on the film’s restoration was given out, and moving introductory speeches were presented by Barbara Fei Ming-yee, the director’s daughter, and Serena Jin, daughter of the producer Jin Xinmin. The screening added electronic subtitles that not only translated the dialogue but identified each speaker—a helpful gesture for a film with many characters and a tangled intrigue.

I can’t comment on it as a representation of Confucius’ thought and life, although experts tell us that it is quite different from the elevated, almost sanctified portrayals that were known before. The plot dramatizes the ineffectuality of the sage’s ideals of civic virtue by showing how power players of his era ignored or undercut his teachings. Scenes from Confucius’ life alternate with scenes of political and military strategy, as warlords and statesmen debate tactics and, not incidentally, calculate how to eliminate Confucius. As Confucius migrates across China, he is unable to halt the continuous warfare among various factions. His disciples leave or die. Just before his death he has only his grandson to care for him. “A great educator, thinker, and philosopher,” Fei Mu writes in an essay, “Confucius was doomed a victim of the politics of his time.”

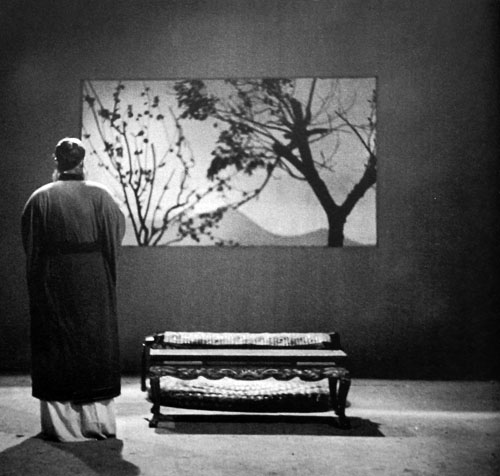

The film is slow-moving and hieratic. Some of the fragments show bits of violence, but the film as a whole relies on dialogue. Although some scenes unfold in natural exteriors, Fei Mu often employs theatrical tableaus, complete with painted landscapes; occasionally the actors cast shadows on the backdrops. The cutting is often axial, simply enlarging a chunk of space as actors declaim their dialogue. The nearly square Movietone frame enhances the symmetry of the compositions, which often feature a window or some other aperture.

Knowing the fluid style of Fei’s 1930s films, we can only regard this rigid, rather ceremonial look as a deliberate artistic choice. In this respect, the film recalls Eisenstein’s Alexander Nevsky and Mizoguchi’s Genroku Chushingura, films of that era aiming to treat a weighty historical subject with solemnity. In Confucius, Fei seems to have been rethinking the relation of cinema to theatre, a quest that preoccupied other directors of the period and that remains important today. Wong Ain-ling’s essay in the booklet aptly notes Rohmer’s Perceval le Gallois as a more recent parallel, and the film likewise has some of the feel of the Straub/ Huillet version of Von heute auf morgen (1997). As often happens, Fei Mu feels like a modern filmmaker.

Confucius was shown across China in 1940 and 1941, and a reedited version was released in 1948. Fei Mu was so upset by the new cut that he took out a newspaper ad denouncing it. Wong Ain-ling, who prepared the documentation for the festival presentation, and Sam Ho, the Archive Programmer, have concluded that this print is likely to have been the re-release version. Sam told me that the archive staff would be spending the next year researching how to integrate the fragments and supply a sense of the original’s design. The Archive is planning to screen that restoration at next year’s festival. Whatever the experts come up with, surely this is a discovery that will be discussed and enjoyed for many years.