Archive for April 2009

Yes, we like it here at the Wisconsin Film Festival

Kristin here-

David has gone halfway around the world to attend a film festival and will be reporting more on what he sees in Hong Kong. But in Madison we have the Wisconsin Film Festival going on now, and there’s plenty to watch here as well, even if it’s only for four days rather than two weeks.

So far I have seen four films in two days and plan to see five more before the festival ends tomorrow night. That means that so far I’ve sat through the short festival prologue film that announces its sponsors four times. Each year we have a different little prologue film. This year director Meg Hamel and her team found a snappy promotional film for Wisconsin that looks like it was made in the late 1950s or early 1960s. Its slogan is “We like it here!” and it features not only our famous dairy and other farm products but also things which are fast disappearing from local industry–like cars and tractors. I’m not sure how I’ll feel about this little film after watching it nine times, but so far it’s amusing.

And our Wisconsin products have followed David to Hong Kong. Shopping for breakfast items in a local grocery store, he found some familiar fare:

We’ve served many a Johnsonville brat during our annual Labor Day cook-out. They look pretty good compared with the pale Chinese version juxtaposed in the photo. And a product from even closer to home, Bagels Forever bagels, which set up shop here in Madison a few years after we did:

Of course, we have Hong Kong imports here as well. I’ve got a ticket to see Johnnie To’s Sparrow tonight.

So far I’ve seen some excellent films. Agnès Varda’s The Beaches of Agnès was a salubrious way to start. It’s an autobiography of sorts, built around visits to the various seaside locales that have played a big part in her life, from childhood visits to the resorts of Belgium to an escape to Corsica to the fishing village that featured in her first film, the 1954 short feature La Pointe-courte to Venice in Los Angeles. Not that her tale is told chronologically. There are numerous diversions, such as meetings with the children who appeared in that first film, now grown old. There are clips from her films and encounters with friends. Varda even managed to get the notoriously camera-shy Chris Marker to participate, though he appears only as a large cat cut-out, and his voice has been altered. (See below.)

Naturally there are passages concerning Varda’s late husband, Jacques Demy, including some candid on-set photos and footage of a very young Catherine Deneuve in costume. We see Varda strolling around an exhibition of her photographs of French movie stars and mourning their deaths, having at 80 outlived most of them. It’s a rambling film and yet somehow all hangs together, with self-deprecating humor, nostalgia, wacky juxtapositions, and moving moments as the director visits old haunts and friends. It was a real crowd-pleaser at the screening I attended, and deservedly so.

Ken Jacobs’ 2006 experimental feature, Razzle Dazzle: The Lost World was a must. Like Tom, Tom, the Piper’s Son, Jacobs’ most famous film, this one takes an early Edison short and plays with it. Parts of the image get  enlarged, frozen, played in slow motion, and colored. Here Jacobs is working not on an optical printer but on a computer, using a single shot that is a view of a large rotating swing full of merrymakers. The result is a movement back and forth between abstract images, representational ones, and combinations where we must struggle to see glimpses of bodies, signs, and walls. I found this theme-and-variations portion of the film to be a bit overlong, with some computer graphics seemingly used simply because they were possible. But there are extraordinary moments. The scene of the swing takes place in daytime, but in the middle section suddenly blackness, superimposed rain, and the sound of thunder transform the scene into a frightening nighttime storm through which the giant swing is dimly visible,continuing to carry its occupants on swoops and glides through the dark. Another passage, illustrated here, manages to suggest a flickering nitrate fire–another frightening moment in a different way.

enlarged, frozen, played in slow motion, and colored. Here Jacobs is working not on an optical printer but on a computer, using a single shot that is a view of a large rotating swing full of merrymakers. The result is a movement back and forth between abstract images, representational ones, and combinations where we must struggle to see glimpses of bodies, signs, and walls. I found this theme-and-variations portion of the film to be a bit overlong, with some computer graphics seemingly used simply because they were possible. But there are extraordinary moments. The scene of the swing takes place in daytime, but in the middle section suddenly blackness, superimposed rain, and the sound of thunder transform the scene into a frightening nighttime storm through which the giant swing is dimly visible,continuing to carry its occupants on swoops and glides through the dark. Another passage, illustrated here, manages to suggest a flickering nitrate fire–another frightening moment in a different way.

The more interesting parts of the film for me were manipulations of stereoscope-card images. By quickly alternating the right and left photos on the cards, Jacobs creates some remarkable effects of apparent motion. (David discussed a similar effect last year in his comments on Capitalism: Child Labor.) Even with only two camera positions represented on the cards, at times an illusion of continuous movement is created, especially in a dramatic shot of ocean waves. There are portions of the image where the water seems to be flowing right to left in an unstopping stream. In other shots the camera seems to be gliding in an arc around the subjects. Jacobs has been doing a lot of experimentation with creating an appearance of 3D using only regular film equipment and still photos, and I for one would have liked to see more of the stereoscope cards and a little less of the play with the Edison shot. But that’s just a quibble. It’s a fascinating film, well worth seeing.

A late addition to the program was the foreign-language Oscar winner Departures. Steve Jarchow, one of the heads of Regent Entertainment, is a Madison native, and he appeared after the film for a lively question-and-answer session. Regent has other forthcoming films in the festival’s schedule, including Tokyo Sonata, which we blogged about from the Palm Springs International Film Festival.

David will probably have something to say about Departures, which he saw last week in a theater in Hong Kong. (He warned us all to bring our tissues, since it’s a good, old-fashioned Shochiku tear-jerker, albeit with many amusing touches.) Steve’s answers to questions put to him by Emeritus Professor Tino Balio and the audience were equally interesting. At a time when Hollywood studios are closing down their art-film niche divisions and foreign-language cinema seems an endangered species, Steve’s company is providing a healthy counter-force. A relatively small firm, it can thrive on titles that bring in a few million dollars–chicken feed by studio standards. Apart from foreign-language titles, Regent is catering to the gay and lesbian market, both for films and television programming. Steve also re-confirmed something that we know well: that Madison is a great town for art cinema, one of the best outside the big metropolitan areas.

From Steven’s Q&A I went off to see Goodbye Solo, Ramin Bahrani’s fifth film, and his third since coming to  wider public attention with Man Push Cart. Roger Ebert has been a champion of Bahrani’s work, and we’ll be seeing his previous feature, Chop Shop, at Ebertfest in a few weeks.

wider public attention with Man Push Cart. Roger Ebert has been a champion of Bahrani’s work, and we’ll be seeing his previous feature, Chop Shop, at Ebertfest in a few weeks.

Goodbye Solo is set in Bahrani’s hometown, Winston-Salem, North Carolina. It deals with a genial Senegalese cab-driver who decides to befriend a prickly white man who he suspects intends to commit suicide. Beautifully shot, the film is to Winston-Salem what Collateral is to Los Angeles, and the final scene in the autumnal Great Smoky Mountains is gorgeous. It’s a moving tale, and one which manages to be emotionally uplifting without falling into the trap of solving all its characters’ problems and becoming a feel-good film.

For those in the Madison area, the festival continues today and tomorrow.

Love isn’t all you need

Pat and Mike.

DB still in HK:

Last week the Hong Kong International Film Festival hosted Gerry Peary’s For the Love of Movies: The Story of American Film Criticism. It’s a lively and thoughtful survey, interspersing interviews with contemporary critics with a chronological account that runs from Frank E. Woods to Harry Knowles. It goes into particular depth on the controversies around Pauline Kael and Andrew Sarris, but it even spares some kind words for Bosley Crowther.

Some valuable points are made concisely. Peary indicates that the alternative weeklies of the 1970s and 1980s were seedbeds for critics who moved into more mainstream venues like Entertainment Weekly. I also liked the emphasis on fanzines, which too often get forgotten as precedents for internet writing. In all, For the Love of Movies offers a concise, entertaining account of mass-market movie criticism, and I think a lot of universities would want to use it in film and journalism courses.

I should declare a personal connection here. I’ve known Gerry since 1973, when I came to teach at the University of Wisconsin—Madison. Like me, he was finishing a dissertation: he was writing a history of the gangster films made before Little Caesar. We spent good lunches together at the Fish Store. Gerry was one of the moving spirits of Madison movie culture—running a film society, writing and editing for the student paper, working with John Davis, Susan Dalton, Tim Onosko, and Tom Flinn on The Velvet Light Trap. I knew I’d come to the right place when somebody would drop by my office to talk about last night’s screening of Underworld or Steamboat ‘Round the Bend.

I should declare a personal connection here. I’ve known Gerry since 1973, when I came to teach at the University of Wisconsin—Madison. Like me, he was finishing a dissertation: he was writing a history of the gangster films made before Little Caesar. We spent good lunches together at the Fish Store. Gerry was one of the moving spirits of Madison movie culture—running a film society, writing and editing for the student paper, working with John Davis, Susan Dalton, Tim Onosko, and Tom Flinn on The Velvet Light Trap. I knew I’d come to the right place when somebody would drop by my office to talk about last night’s screening of Underworld or Steamboat ‘Round the Bend.

Like many of our generation, Gerry became a mixture of critic and academic. He taught at several colleges, wrote for The Boston Phoenix, and published books, notably Women and the Cinema: A Critical Anthology (1977) and The Modern American Novel and the Movies (1977). Most recently he’s edited collections of interviews with Tarantino and John Ford. He has moved smoothly into online publishing with a packed and wide-ranging website.

Gerry’s documentary comes along at a parlous time, of course. Most of the footage was taken before the wave of downsizings that lopped reviewers off newspaper staffs, but already tremors were registered in some interviewees’ remarks. Apart from this topical interest, the film set me thinking: Is love of movies enough to make someone a good critic? It’s a necessary condition, surely, but is it sufficient?

Gerry’s film includes the inevitable question: What movie imbued each critic with a passion for cinema? I have to say that I have never found this an interesting question, or at least any more interesting when asked of a professional critic than of an ordinary cinephile. Watching Gerry’s documentary made me think that everybody has such formative experiences, and nearly everybody loves movies. But what sets a critic apart?

Elsewhere, I’ve argued that a piece of critical writing ideally should offer ideas, information, and opinion—served up in decent, preferably absorbing prose. This is a counsel of perfection, but I think the formula ideas + information + opinion + good or great writing isn’t a bad one.

You really can’t write about the arts without having some opinion at the center of your work. Too often, though, a critic’s opinions come down simply to evaluations. Evaluation is important, but it has several facets, as I’ve tried to suggest here. And other sorts of opinions can also drive an argument. You can have an opinion about the film’s place in history, or its contribution to a trend, or its most original moments. Opinions like these allow you to build an argument, drawing on evidence or examples in or around the movie in question. Several of our blog entries on this site are opinion-driven, but not necessarily evaluations of the movies.

Most people think that film criticism is largely a matter of stating evaluations of a film, based either in criteria or personal taste, and putting those evaluations into user-friendly prose. If that’s all a critic does, why not find bloggers who can do the same, and maybe better and surely cheaper than print-based critics? We all judge the movies we see, and the world teems with arresting writers, so with the Internet why do we need professional critics? We all love movies, and many of us want to show our love by writing about them.

In other words, the problem may be that film criticism, in both print and the net, is currently short on information and ideas. Not many writers bother to put films into historical context, to analyze particular sequences, to supply production information that would be relevant to appreciating the movies. Above all, not many have genuine ideas—not statements of judgments, but notions about how movies work, how they achieve artistic value, how they speak to larger concerns. The One Big Idea that most critics have is that movies reflect their times. This, I’ve suggested at painful length, is no idea at all.

Once upon a time, critics were driven by ideas. The earliest critics, like Frank Woods and Rudolf Arnheim, were struggling to define the particular strengths of this new art form. Later writers like André Bazin and the Cahiers crew tried to answer tough idea-based questions. What is distinctive about sound cinema? How can films creatively adapt novels and plays? What are the dominant “rules” of filmmaking ? (And how might they be broken?) What constitutes a cinematic modernism worthy of that in other arts? You could argue that without Bazin and his younger protégés, we literally couldn’t see the artistry in the elegant staging of a film like George Cukor’s Pat and Mike. Manny Farber, celebrated for his bebop writing style, also floated wider ideas about how the Hollywood industry’s demand for a flow of product could yield unpredictable, febrile results.

One of the reasons that Sarris and Kael mattered, as Gerry’s documentary points out, was that they represented alternative ideas of cinema. Sarris wanted to show, in the vein of Cahiers, that film was an expressive medium comparable in richness and scope to the other arts. One way to do that (not the only way) was to show that artists had mastered said medium. Kael, perhaps anticipating trends in Cultural Studies, argued that cinema’s importance lay in being opposed to high art and part of a raucous, occasionally vulgar popular culture. This dispute isn’t only a matter of taste or jockeying for power: It is genuinely about something bigger than the individual movie.

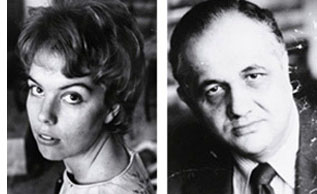

During the Q & A, it emerged that at the same period critics’ ideas had an impact on filmmaking. Sarris’s promotion of the director as prime creator, with a bardic voice and a personal vision, was quickly taken up by Hollywood. Now every film is “a film by….” or “ a … film”: auteur theory shows up in the credits. Similarly, the concept of film noir was constructed by French critics and imported to the US by Paul Schrader. Suddenly, unheralded films like The Big Combo popped up on the radar. Today viewers routinely talk about film noir, and filmmakers produce “neo-noirs.” It seems to me as well that Hollywood became somewhat more sensitive to representation of women after Molly Haskell (here, alongside Sarris) had brought feminist ideas to bear on the American studio tradition, avoiding simple celebration or denunciation. Film criticism had a robust impact on the industry when it trafficked in ideas.

During the Q & A, it emerged that at the same period critics’ ideas had an impact on filmmaking. Sarris’s promotion of the director as prime creator, with a bardic voice and a personal vision, was quickly taken up by Hollywood. Now every film is “a film by….” or “ a … film”: auteur theory shows up in the credits. Similarly, the concept of film noir was constructed by French critics and imported to the US by Paul Schrader. Suddenly, unheralded films like The Big Combo popped up on the radar. Today viewers routinely talk about film noir, and filmmakers produce “neo-noirs.” It seems to me as well that Hollywood became somewhat more sensitive to representation of women after Molly Haskell (here, alongside Sarris) had brought feminist ideas to bear on the American studio tradition, avoiding simple celebration or denunciation. Film criticism had a robust impact on the industry when it trafficked in ideas.

You can argue that these are old examples. What new ideas are forthcoming from mainstream film criticism? In the Q & A Gerry, like the rest of us, couldn’t come up with many. On reflection, I wonder if the rise of academic film studies forced ideas to migrate to the specialized journals and the Routledge monograph. These ideas also had a different ambit—sometimes not particularly focused on cinema, or on aesthetics, or on creative problem-solving.

Of course ideas don’t move on their own. A more concrete way to put this is that bright, conceptually oriented young people who in an earlier era would have become journalistic critics became professors instead. The division of labor, it seems, was to aim Film Studies at an increasingly esoteric elite, and let film reviewers address the masses. It’s an unhappy state of affairs that we still confront: recondite interpretations in the university, snap evaluations in the newspapers. You can also argue that print reviewers, by becoming less idea-driven, paved the way for DIY criticism on the net.

What about information, the other ingredient I mentioned? If we think of film criticism as a part of arts journalism, we have to admit that most of it can’t compare to the educational depth offered by the best criticism of music, dance, or the visual arts. You can learn more from Richard Taruskin on a Rimsky performance or Robert Hughes on a Goya show than you can learn about cinema from almost any critic I can think of. These writers bring a lifetime of study to their work, and they can invoke relevant comparisons, sharp examples, and quick analytical probes that illuminate the work at hand. Even academically trained film reviewers don’t take the occasion to teach.

Most of the print criticism I’ve seen today is remarkably uninformative about the range and depth of the art form, its traditions and capacities. Perhaps editors think that film isn’t worthy of in-depth writing, or perhaps their readers would resist. As if to recall the battles that Woods, Arnheim and others were fighting, cinema is still not taken seriously as an art form by the general public or even, I regret to say, by most academics.

Yet other aspects of information could be relevant. Close analysis offers us information about how the parts work together, how details cohere and motifs get transformed. For an example of how analysis can be brought into a newspaper’s columns, see Manohla Dargis on one scene in Zodiac.

I’d also be inclined to see description—close, detailed, loving or devastating—as providing information. It’s no small thing to capture the sensuous surface of an artwork, as Susan Sontag put it. Good critics seek to evoke the tone or tempo of a film, its atmosphere and center of gravity. We tend to think that this is a matter of literary style, but it’s quite possible that sheer style is overrated. (Yes, I’m thinking of Agee.) Thanks to our old friends adjective and metaphor, even a less-than-great writer can inform us of what a film looks and sounds like.

I’d also be inclined to see description—close, detailed, loving or devastating—as providing information. It’s no small thing to capture the sensuous surface of an artwork, as Susan Sontag put it. Good critics seek to evoke the tone or tempo of a film, its atmosphere and center of gravity. We tend to think that this is a matter of literary style, but it’s quite possible that sheer style is overrated. (Yes, I’m thinking of Agee.) Thanks to our old friends adjective and metaphor, even a less-than-great writer can inform us of what a film looks and sounds like.

In any event, I’m coming to the view that the greatest criticism combines all the elements I’ve mentioned. As so often in life, love isn’t always enough.

Gerry’s documentary doesn’t distinguish between critics and reviewers, but we probably should. Reviewers typically give us opinions and a smattering of information (plot situations, or production background culled from presskits), wrapped up in a writing style that aims for quick consumption. Today anybody with a web connection can be a reviewer.

Exemplary critics try for more: analysis and interpretation, ideas and information, lucidity and nuance. Such critics are as rare now as they have ever been. Far from being threatened by the Internet, however, they have more opportunities to nourish film culture than ever before.

The Big Combo.

PS 4 April (HK time): Thanks to Justin Mory for correcting a name error in the original post!

The movie looks back at us

DB, still at the Hong Kong International Film Festival:

Abbas Kiarostami has the widest octave range of any filmmaker I know.

His humane dramas of Iranian life, from The Traveller to The Wind Will Carry Us, have justly won acclaim on the arthouse circuit. He has written scripts as well, some—like the under-seen The Journey (1994)—that are as compelling as a psychological thriller. He can conjure suspense out of the simplest acts, such as whether an adult will rip up a child’s copybook (Where Is the Friend’s Home?) or whether a four-year-old boy locked in with his baby brother can figure out how to turn off a stove (The Key). Indeed, I think that one of the great accomplishments of much modern Iranian cinema, with Kiarostomi in the vanguard, has been to reintroduce classic dramatic suspense into arthouse moviemaking.

But at times Kiarostami has moved to an opposite pole, that of extreme minimalism and “dedramatization.” The drift toward a hard-edged structure was there in Ten (2002), which gave us one of his drive-through dramas—people conversing in the front seat of a car—but in severe permutational form (different drivers, different passengers). Rigor was pushed to an extreme in Five Dedicated to Ozu (2003): Five lengthy shots of water landscapes, each many minutes long, taken at different times of day. The biggest dramatic action was the ducks walking through the frame. With Kiarostami, it seems, we cinephiles can have it all—Hitchcock and James Benning in the same filmmaker.

Now Shirin (aka My Sweet Shirin, 2008) marks another highly original exploration. I don’t expect to see a better film for quite some time.

After a credit sequence presenting the classic tale Khosrow and Shirin in a swift series of drawings, the film severs sound from image. What we hear over the next 85 minutes is an enactment of the tale, with actors, music, and effects. But we don’t see it at all. What we see are about 200 shots of female viewers, usually in single close-ups, with occasionally some men visible behind or on the screen edge. The women are looking more or less straight at the camera, and we infer that they’re reacting to the drama as we hear it.

That’s it. The closest analogy is probably to the celebrated sequence in Vivre sa vie, in which the prostitute played by Anna Karina weeps while watching La Passion de Jeanne d’Arc. Come to think of it, the really close analogy is Dreyer’s film itself, which almost never presents Jeanne and her judges in the same shot, locking her into a suffocating zone of her own.

Of course things aren’t as simple as I’ve suggested. For one thing, what is the nature of this spectacle? Is it a play? The thunderous sound effects, sweeping score, and close miking of the actors don’t suggest a theatrical production. So is it a film? True, some light spatters on the edge of the women’s chadors, as if from a projector behind them, but no light seems to be reflected from the screen. In any case, what’s the source of the occasional dripping water we hear from the right sound channel? The tale is derealized but it remains as vivid on the soundtrack as the faces are on the image track. What the women watch is, it seems, a composite, neither theatrical nor cinematic—a heightened idea of an audiovisual spectacle.

Moreover, there are the faces. We see some more than once, but new ones are introduced throughout. Spatially, they float pretty free; only occasionally do we get a sense of where the women are sitting in relation to one another. All are stunningly beautiful, whether young or old. We get an encyclopedia of expressions—neutral, alert, concentrated, bemused, amused, pained, anxious. During a battle scene, faces turn away, eyes lower, and hands shift nervously. The best person to review this movie is probably Paul Ekman, world expert on the nuances of facial signaling.

The weeping starts, by my count, about thirty-eight minutes in, during a rain scene uniting the two lovers Shirin and Khosrow. Thereafter, tears run down cheeks, along jaws and mouths, down necks and nostrils. The film is an almost absurdly pure experiment in facial empathy. It arouses us us by our sense of the story unfolding elsewhere, somewhere behind us, enhanced by lyrical vocalise and brusque sound effects, but above all by these eloquent expressions. It’s a feast for our mirror neurons. If you’re interested in reaction shots, you have to recall Dreyer remarking that “The human face is a landscape that you can never tire of exploring.”

I once asked Kiarostami how he got the remarkable performances in shot/ reverse-shot that we see in films like Through the Olive Trees and The Taste of Cherry. He said that he simply filmed one actor saying all his lines and giving all his reactions, then filmed the other. Often the two actors were never present at the same time, especially when he shot the car sequences. This montage-based approach, creating a synthetic space simply by cutting, has been taken to an extreme in Shirin, where the soundtrack supplies the reverse shot we never see. We’re told that Kiarostami filmed his female actors here reacting to dots on a board above the camera! Indeed, Kiarostami claims he decided on the Shirin story after filming the faces. Despite that, Shirin becomes one of the great ensemble pieces of screen acting, although the actors almost never share a real time and space. (Take that, green-screen wizards!) Like Godard, Kiarostami has been busy reinventing the Kuleshov effect (perhaps by way of Bresson).

This catalogue of female reactions to a tale of spiritual love reminds us that for all the centrality of men to his cinema, Kiarostami has also portrayed Iranian women as decisive, if sometimes mysterious, individuals. Women stubbornly go their own way in Through the Olive Trees and Ten. The premises of Shirin were sketched in his short, “Where Is My Romeo?” in Chacun son cinema (2007), in which women watch a screening of Romeo and Juliet. But the sentiments of that episode are given a dose of stringency here, particularly in one line Shirin utters: “Damn this man’s game that they call love!”

One last note: Kiarostami built movie production into the plot of Through the Olive Trees. Now he has given us the first fiction film I know about the reception of a movie, or at least a heightened idea of a movie. What we see, in all these concerned, fascinated faces and hands that flutter to the face, is what we spectators look like—from the point of view of a film.

For more on the production background, see the lengthy interview with Kiarostami here.