Archive for May 2009

The postman has rung more than twice

Optical Vacuum.

DB here:

While I try to whip up seven lectures for the Bruges Summer Film College and a couple more for the University of Copenhagen and our June Society for Cognitive Studies of the Moving Image confab, I offer some quick notes on notable DVDs and books lugged to our door by our mailman.

When machines film better than they know

Snow blankets a terrace and the furniture on it. A bottle jerks back and forth on a pavement. Christmas lights blink on and off. Everything looks desolate. What people we see scuttle across washed-out landscapes, play mahjongg in stammering gestures, and toil in computer labs under glaring fluorescent lights. What planet are we on?

These images are available to any of us. For two years Dariusz Kowalski trawled through sites like www.opentopia.com for surveillance-camera footage. He chose only material from hidden cameras. He added nothing except some slow motion (“otherwise it would be too fast”) and a voice-over commentary from artist Stephen Mathewson reading passages from a year’s diary. The result was a fifty-five minute assemblage film called Optical Vacuum (2008), which I saw and admired in Hong Kong back in April.

Sometimes the diary account intersects with what we see: Mathewson talks of washing his laundry/ shots of a Laundromat. More often, the voice drifts off on its own. Optical Vacuum isn’t an effort to make a film essay or to create a complex audiovisual dynamic. Mathewson’s diary provides an intimacy that the footage lacks, but I think the film would stand up strongly without it.

As a flow of impersonal views, usually from a distant perch, the footage creates a bleak beauty.

Occasionally a human operator has commanded the camera to focus on something, usually a woman.

But most often the camera is just mindlessly recording.

In the process, the surveillance camera reinvents avant-garde film—not just the barely inflected fields of Structural cinema, but also the time compression and melting glimpses, the reflections and superimpositions, the transient ghosts and brutal geometry we find in silent experimental work by Richter, Vertov, and others. These stupid cameras can’t help turning reality into something else. They don’t know any better.

Optical Vacuum, along with other pieces by Kowalski, can be found on a PAL uncoded DVD from the extraordinary Austrian collective sixpack. The handsomely mounted Index release is available here, and elsewhere on the Net.

Dragons and tigers in the Udine sun

Italian festivals of specialized cinema are mounted with incomparable flair–lots of screenings, panels, interviews, book sales, and of course outstanding food. Most famous are Pordenone’s festival of silent cinema and Bologna’s Cinema Ritrovato. But for admirers of Asian cinema, just as important is the Udine Far East Film event, which completed its eleventh installment on 2 May.

Italian festivals of specialized cinema are mounted with incomparable flair–lots of screenings, panels, interviews, book sales, and of course outstanding food. Most famous are Pordenone’s festival of silent cinema and Bologna’s Cinema Ritrovato. But for admirers of Asian cinema, just as important is the Udine Far East Film event, which completed its eleventh installment on 2 May.

Alas, I’ve never been. In its earliest years it overlapped with the Hong Kong film festival; more recently, my commitments elsewhere, such as Ebertfest, have kept me away. But I have followed this celebration of Asian cinema at a distance through its remarkable publications.

The Udine event concentrates on popular cinema, mostly recent releases that are unlikely to come to US theatres or video stores. You can see films from Japan, Korea, and China but also from Thailand, Malaysia, and the Philippines. This year’s highlights include regional hits like Cape no. 7, Beast Stalker, Departures, and Ip Man as well as obscure and delirious items like Love Exposure and The Forbidden Legend: Sex and Chopsticks. Many screenings are European premieres.

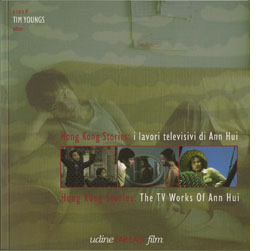

The programmers also mount adventurous retrospectives of rare items. One year it was a survey of the work of Patrick Tam, still too little known among Asian aficionados. This year the retrospective was devoted to Ann Hui’s TV films, which are among her best work. These films, shot in 16mm and broadcast in the 1970s, were strong meat for a culture unused to social criticism in its popular media. Hui’s dramas showed police corruption, the sex trade, abandoned children, and drug addiction. The episodes were researched and scripted under great time pressure, and Hui was allotted two weeks for shooting and post-production. “We were experts at shooting in the streets on the sly.” The stories’ concern for ordinary people and their problems has resurfaced again in The Way We Are (2008) and Night and Fog (2009).

The Hui volume is a model of the profuse documentation the Far East festival provides. Several concise essays, all in both English and Italian, enhance appreciation of the films. Contributors Law Kar, Shu Kei, and editor Tim Youngs do a fine job of situating Hui’s TV work in its context, and a lengthy interview with the director explores her working methods and intentions. There’s also valuable filmographic information about the episodes (four of them available on DVD).

The Hui volume is a model of the profuse documentation the Far East festival provides. Several concise essays, all in both English and Italian, enhance appreciation of the films. Contributors Law Kar, Shu Kei, and editor Tim Youngs do a fine job of situating Hui’s TV work in its context, and a lengthy interview with the director explores her working methods and intentions. There’s also valuable filmographic information about the episodes (four of them available on DVD).

As if this weren’t enough, the Udine event publishes a mammoth catalogue called Nickelodeon. Each year it’s a treasure chest of enthusiastically presented information. This time around, surveys of 2008 developments in all the major countries are accompanied by Roger Garcia‘s special section on the history of Thai action cinema. A vast section of reviews of the films to be shown rounds out this gift to the Asian cinephile. (A little of this material is available at the Udine site.) There is no coordinated effort to sell the books to the public, but if you want to purchase them, try writing to the festival directors at cec@cecudine.org.

So a tip of the hat to the dedicated Udine team, headed by Sabrina Baracetti, and a signal to you that if you have the time and the money to go, you would surely have a hell of a week. (Note that professors and students are offered lodging for some nights.) Who knows? A director might show up to put the audience in a movie, as Johnnie To once did. Even if you can’t make the trip, the quality of the publications makes them indispensible for research and enjoyable reading.

Rabbits from a hat

It’s tiresome to hear novelists kvetching that film adaptations mangle their work. So it’s a pleasure to read Christopher Priest’s brisk account of how his novel The Prestige became a film. In The Magic: The Story of a Film Priest takes us through the whole process, but this isn’t the usual behind-the-scenes tour. He never visited the set or met the principals. Instead we get the viewpoint of a writer living in East Sussex, following the production through agents’ correspondence and the gossip frothing up on Google Alerts.

It’s tiresome to hear novelists kvetching that film adaptations mangle their work. So it’s a pleasure to read Christopher Priest’s brisk account of how his novel The Prestige became a film. In The Magic: The Story of a Film Priest takes us through the whole process, but this isn’t the usual behind-the-scenes tour. He never visited the set or met the principals. Instead we get the viewpoint of a writer living in East Sussex, following the production through agents’ correspondence and the gossip frothing up on Google Alerts.

Priest is a lively writer, and he is frank about the ups and downs of the process. Initially he is happy that Nolan acquired the rights because the novel, a cunningly designed piece of misdirection, seems ideal for the director of Memento. But he confesses disappointment when the Prestige project is sidetracked by Batman Begins (“overlong, simplistic, and dull”). When the production gets under way, there are more swerves in the road. Given an early script, Priest admires the craftsmanship of Jonathan Nolan. But then he’s baffled that Christopher Nolan is saying two inconsistent things: that the film is completely different from the book, and that reading the book will spoil the film. Then again, during a press preview in Leicester Square, Priest succumbs to the film’s intricacies. “It has one of the most complicated and sophisticated narrative structures ever seen in an entertainment film.”

The story of the production ends here, but Priest goes on for about fifty pages to analyze the film in considerable detail. He dwells on the opening, which has no equivalent in his novel, and praises it for its fluent shifts among different points in story time. He appraises various aspects of the film, and he doesn’t stint criticisms. He notes that the Nolans stripped off his contemporary story, crucially altered the roles of the women, and turned his elusive mysteries into plot-driven secrets. Yet he concludes:

There is hardly a line of dialogue or moment of action in the film that can be traced back word-for-word, yet the whole thing is faithful to the novel in spirit, in story and in effect. I have differences with the screenplay in places, but none of those detracts from my general impression that it is a classic film adaptation of an existing novel, one which intending screenwriters would do well to study alongside the novel. (157).

Priest is a former movie critic (for the sturdy old British Film Institute publication Film) and an astute observer of what happens in a shot and on a soundtrack. He contacted me after my March blog entry discussing micro-repetitions in The Prestige and told me of The Magic. I ordered a copy pronto, and I’m glad I did. If you want to give your mail carrier a bit more job security, go to this page and click on GrimGrin Studio.

Forgotten but not gone: more archival gems on DVD

Kristin here-

We don’t make a practice of regularly reviewing DVDs here, but when a special release comes along that makes historically important, hard-to-see films available, we like to point it out. David spotlighted the new Criterion set of Shimizu Hiroshi films, and this week it’s Lotte Reiniger and Belgian experimental silents.

The lady with the flying scissors

Up until recently, the name Lotte Reiniger meant little to most people. Some were aware that she, rather than Walt Disney, had made the first animated feature film, The Adventures of Prince Achmed (1926). Some had been lucky enough to see a few of her shorts, created with a delicate silhouette technique using hinged, cut-out puppets. She had pioneered the approach in the late 1910s and continued to use it in much the same way up to her last films in the 1960s and 1970s.

Now, however, in another of the marvelous revelations that DVDs have made possible, we are in the process of having virtually all of Reiniger’s surviving work become available over a short stretch of time.

Early this year the British Film Institute released a two-disc set, “Lotte Reiniger: The Fairy Tale Films.” It concentrates on a series of thirteen films Reiniger and her husband Carl Koch made for television during an intensely productive period in 1954-55.

Two of these, Aladdin and the Magic Lamp and The Magic Horse, recycle footage from The Adventures of Prince Achmed, the elaborateness and delicacy of which stand out. Yet the rest of the series, though clearly made on a lower budget and remarkably quickly, are consistently excellent, with considerable detail of gesture and a great deal of wit (as in Thumbelina, right).

The rest of the program includes the 1922 Cinderella (left) which is Reiniger at her prime-though the detail of  one of the stepsisters slicing off part of her foot to make it fit in the tiny slipper may be a bit grim for some children. The Death-Feigning Chinaman (1928) is a fascinating item, a sequence cut from Prince Achmed and released as a free-standing tale. Reiniger made The Golden Goose (1944) in Berlin late in the war, as she cared for her ailing mother. It was not edited into a silent version until 1963, with a soundtrack being added for TV in 1988. It’s a real treasure that belies the grim circumstances of its making.

one of the stepsisters slicing off part of her foot to make it fit in the tiny slipper may be a bit grim for some children. The Death-Feigning Chinaman (1928) is a fascinating item, a sequence cut from Prince Achmed and released as a free-standing tale. Reiniger made The Golden Goose (1944) in Berlin late in the war, as she cared for her ailing mother. It was not edited into a silent version until 1963, with a soundtrack being added for TV in 1988. It’s a real treasure that belies the grim circumstances of its making.

The material following chronologically after the thirteen television episodes consists of three films. One, The Little Chimney Sweep, is the only disappointment in the program. It’s a revised, abridged version of a film from 1934, and the voiceover narration and truncated action downplay the subtle touches and charm that characterize all the other films. Fortunately the original survives and will be presented in the DVD program of the musical films.

The other two films are in color. I had never seen a color Reiniger film, but both are lovely, like old-fashioned children’s book-illustrations come to life. Jack and the Beanstalk (see image above) is the more polished of the two. Here black silhouette figures move amid brightly colored, stylized landscapes. It doesn’t sound like it should work, but it does. The Frog Prince is more what one would expect, with hinged colored puppets replacing the dark silhouettes. The result is highly engaging, though the lack of expression in the characters, which works so well for the dark silhouettes, might become too apparent in a film lasting more than a few minutes.

Wonderful though it is to have this big dose of Reiniger made available, I wish that the BFI had organized its presentation more helpfully. For a start, there’s no indication that this set is part of an ongoing series that will eventually make most of the filmmaker’s work available. No reference to that fact that the BFI already put out The Adventures of Prince Achmed in 2001, accompanied by an hour-long documentary, Lotte Reiniger: Homage to the Inventor of the Silhouette Film, directed by Katja Raganelli (which isn’t is also on the American disc released by Milestone). No announcement that a set of Reiniger’s music-based animated shorts is due out later this year or that the second set of GPO advertising shorts also due soon will include some Reiniger works (The Tocher and The H.P.O.), though brief references to that future release are buried in a couple of the program notes. (The two Reiniger films are already available on a British DVD called The GPO Story.) Only diligent trawling about the internet reveals such things. There’s a good summary of the situation in the DVD Times review of the fairy-tales set.

The program notes are fairly informative if you want plot synopses, but they provide virtually no historical context. There’s no general introduction to the program or the overall series, just a brief biographical note on Reiniger and notes on the individual films. I would have appreciated some information on the 1954 television series for which many of the films in the set were made.

Speaking of plot synopses, the notes for The Death-Feigning Chinaman miss a key narrative point. The title character, Ping Pong, gets drunk and starts eating a cooked fish that a young couple give him. The description continues, “Ping Pong eats a little of the fish, then tramples it in a drunken rage and falls down in a stupor.” This is a key moment, since his apparent death launches a snowballing accumulation of confusion, confession, and near execution. What actually happens is that Ping Pong chokes on a bone while eating the fish, and it paralyzes him. At the climax, an insect lands on his nose, he sneezes, the bone flies out of his mouth, and he emerges from his “death.”

Another instance of disorganization comes with a charming little color film, The Frog Prince, from 1961. It  was originally creates as an interlude in a stage pantomime, and on the disc it is presented silent. The program note comments, “No evidence of a soundtrack survives, and indeed sound seems unbefitting for a pantomime interlude. Although surprisingly, the aperture format of this mute positive print is 1:1.375 with an unused soundtrack area.” Yet the short documentary included in the set, The Art of Lotte Reiniger, includes The Frog Prince in its entirety, accompanied by lively and quite appropriate orchestral music. Given that Reiniger’s own production company made this film and she participated in its creation, it seems highly probable that the music used in the documentary was either the intended accompaniment for the film or at least considered suitable for it. A case of the right hand not knowing what the left is doing when this package was being put together, I guess.

was originally creates as an interlude in a stage pantomime, and on the disc it is presented silent. The program note comments, “No evidence of a soundtrack survives, and indeed sound seems unbefitting for a pantomime interlude. Although surprisingly, the aperture format of this mute positive print is 1:1.375 with an unused soundtrack area.” Yet the short documentary included in the set, The Art of Lotte Reiniger, includes The Frog Prince in its entirety, accompanied by lively and quite appropriate orchestral music. Given that Reiniger’s own production company made this film and she participated in its creation, it seems highly probable that the music used in the documentary was either the intended accompaniment for the film or at least considered suitable for it. A case of the right hand not knowing what the left is doing when this package was being put together, I guess.

The Art of Lotte Reiniger is a fascinating little film, despite the rocky sound quality of the surviving print. The filmmaker shows off her storyboards and puppets, but the really amazing thing is watching how quickly she cuts the silhouettes, freehand, out of black paper.

For those who read German and want as full a dose of Reiniger as possible, an 8-disc box is already available, including Prince Achmed, the fairy-tale and music shorts, and a two-disc set called “Dr. Dolittle & Archivschatze” (Dr. Dolittle and archive treasures).

Animation historian William Moritz provides a biographical note and filmography for Reiniger here. It or something like it would have been a helpful introduction to the DVD booklet.

“This is not a pipe,” the movie

As of February of this year, I have been visiting the Cinémathèque royale de Belgique/the Koninklijk Film Archief, or, unofficially, the Royal Film Archive of Belgium, for thirty years now. (David made his first visit there in 1982.) It has been a tremendous resource for us, and its staff, especially current archive director Gabrielle Claes, have invariably been generous and welcoming.

Being a government-supported institution in a bilingual country, the Archive renders all texts in French and Flemish, from the monthly screening schedules to the subtitles that sprawl across the bottoms of frames. Now, as part of a renovation of the screening venue and museum space, the Royal Film Archive has abandoned all that verbiage and officially renamed itself the Cinematek. That’s not a real word in any language, but it conveys more or less the same thing in French, Flemish, and English. I suspect that the epic subtitles will remain. For full details of the new facility and programming, go here.

Before the name change, the archive had started a DVD series awkwardly entitled “filmarchief dvd’s – les dvd de la cinémathèque.” These are collections of archival films mostly relating to Belgium, and a lot of them are documentaries. The series includes an excellent new two-disc set, “Avant-Garde 1927-1937.” (The archive also publishes modern films, mostly in Flemish.) It’s in fact a trilingual release, with the subtitle “Surréalisme et expérimentation dans la cinéma belge/Surealisme en experiment in de Belgische cinema/Surrealism and experiment in Belgian cinema.” The text of the detailed accompanying booklet is in all three languages, and the discs also offer options for subtitles in any of the three. The producers have taken great care with the music, commissioning Belgian musicians to compose and perform modernist chamber-orchestra scores. These vary considerably, effectively matching the tone and style of each film. The design of the packaging is practical and sturdy: it’s a small hard-cover book with the pages containing the text and the discs fastened onto the endpages.

Belgian silent experimental cinema might sound a bit obscure, but recall that the country had a pretty prominent role in the Surrealist movement, mostly famously with painter René Magritte. Categorizing all the films on these discs as Surrealist is a bit of a stretch. Some fit that designation, but others are more like city symphonies and political documentaries, and a couple defy definition. But if the label attracts more attention, all the better. Henri Storck and Charles Dekeukeleire, the filmmakers whose works dominate the set, are major filmmakers, and the two shorts that fill out the discs are of historical interest–and genuinely Surrealist.

Storck has long been better remembered than Dekeukeleire. He helped form the national film archive in the late 1930s, and he went from experimental cinema in the 1920s to become a prominent documentarist for the rest of his career. His collaboration with Joris Ivens, Misère au Borinage (1933), is a classic in the genre.

Disc One

Storck dominates the first disc with four titles. his Images d’Ostende (1929) is a quiet study of the seaside resort town where the filmmaker was born. It’s a lovely debut, revealing his eye for composition and  feeling for nature. There’s nothing Surrealist about it. It’s closer to some of the more familiar lyrical studies of the era, like Ivens’ Rain. The accompanying music is modernist with a 1920s feel; a soprano voice weaves subtly through the instrumentation.

feeling for nature. There’s nothing Surrealist about it. It’s closer to some of the more familiar lyrical studies of the era, like Ivens’ Rain. The accompanying music is modernist with a 1920s feel; a soprano voice weaves subtly through the instrumentation.

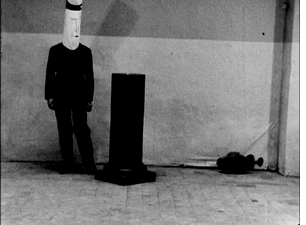

The second film, Pour vos beaux yeux (1929), is a fiction film and definitely Surrealist. The story is minimal. A man finds a false eye lying on the ground. He visits a prosthetics shop, makes plans involving maps, and contemplates the eye on a pedestal while wearing a peculiar cylindrical mask (left). Eventually he wraps the eye in a box and attempts to mail the package.

The program notes claim that Storck could not have seen Un chien andalou when he made Pour vos beaux  yeux. That’s difficult to believe, given that the film seems almost to be an elaborate riff on that film’s eyeball-slitting shot. There are definite references to Ballet mécanique, and the seashells that line the desk where the protagonist wraps the package recall Germaine Dullac’s La coquille et le clergyman.

yeux. That’s difficult to believe, given that the film seems almost to be an elaborate riff on that film’s eyeball-slitting shot. There are definite references to Ballet mécanique, and the seashells that line the desk where the protagonist wraps the package recall Germaine Dullac’s La coquille et le clergyman.

Storck had obviously seen Eisenstein films as well, including October. Histoire du soldat inconnu (1932) is made up of footage from 1928, when an anti-war treaty had been signed. The filmmaker uses intellectual montage to make the point that militarism and the institutions that support it are clearly going to make mincemeat of the treaty’s ideals. The approach is pretty simple, juxtaposing marching soldiers with religious processions. At that point in film history, it was probably still a pretty novel idea that one could cut from a pompous politician speaking to a small dog yapping. By now it looks pretty heavy-handed.

Indeed, the next film in the program, Sur les bords de la caméra (also 1932, also incorporating found footage from 1928) uses the same technique with more restraint. It reminded me a little of Bruce Conner’s A Movie, where odd juxtapositions gradually come to seem more sinister and finally disastrous. Scenes of groups exercising, religious processions, shots in traffic and in prison, all add up to a suggestion that a whole population is voluntarily doing regimented things controlled by the police and other authorities.

On my first visit to the Royal Film Archive back in 1979, one of the titles on my to-see list was Impatience, an experimental film by Charles Dekeukeleire. I had seen a reference to it in the British-Swiss journal of film art, Close-Up. Jacques Ledoux, director of the archive, was delighted that anyone should want to see a film by this nearly forgotten director. He urged me to see Deukeukeleire’s other experimental films, all made in the 1920s and early 1930s before he, too, moved into documentary work.

I saw Combate de boxe (1927), made when Dekeukeleire was only 22. Combining negative and positive footage, hand-held camera, rapid montage, masks–pretty much all the devices of the European avant-garde of the day–he strove to give the subjective impressions of the two combatants in the ring. That’s the first of four Dekeukeleire films in this set. It’s an impressive film by a very young, talented man–but not one that suggests the highly original artist that he would soon become.

The last film on disc one skips forward to 1932, when Dekeukeleire made Visions de Lourdes. Beginning with conventionally beautiful mountain vistas, the film slowly moves toward the area around the sacred grotto and finally to shots within the grotto itself. There are shots of shop-windows full of Lourdes souvenirs (including candy made with holy water from the shrine), but these come in fairly late, avoiding a blatant focus on the commercialization of the site and the notion that those hoping to be healed of illness and deformity are being exploited.

Clearly Dekeukeleire has a more original sense of composition than does Storck. There is a motif of old women selling candles that the filmmaker turns into a series of shots that look like something out of Eisenstein’s Mexican footage–which of course Dekeukeleire could not have seen. (See the image at the bottom, which has enough gap framing to impress even David.) The film is critical of the church, but subtly so–and perhaps mainly because we’ve been cued to take it that way, especially in this case by the dissonant music. I wonder if, in a different context and with a cheerier soundtrack, some of the devout might actually take it as a serious tribute to the healing powers of the saint. They would be mistaken, I think, but the film is understated enough that I think it’s possible.

Disc Two

Dekeukeleire’s two masterpieces, however, were made between these Combat de boxe and Visions de Lourdes. Impatience (1928) is an abstract film that hints maddeningly at a possible narrative situation that never develops. Instead, shots of  four “personnages,” a woman, a motorcycle, a mountainous landscape, and three abstract blocks are edited together. None of these elements is every seen in a shot with any of the others. Rapid montage, vertiginous views against blank backgrounds, upside-down framings, and ruthless, unvarying stretches of repetition make this one of the most challenging, opaque films of its era.

four “personnages,” a woman, a motorcycle, a mountainous landscape, and three abstract blocks are edited together. None of these elements is every seen in a shot with any of the others. Rapid montage, vertiginous views against blank backgrounds, upside-down framings, and ruthless, unvarying stretches of repetition make this one of the most challenging, opaque films of its era.

Perhaps in the wake of post-World War II experimental cinema, where spectator frustration and the denial of conventional beauty and entertainment are often part of a film’s intent (Michael Snow’s Wavelength comes to mind), we are better equipped to understand a film like Impatience, which in its day baffled most reviewers and audiences. Indeed, now Impatience is widely considered to be the best of Dekeukeleire’s avant-garde films.

I think that’s partly because one can at least classify it as an abstract film. For me, his next and longest experimental work, Histoire de detéctive (1929), is even more daring. It purports to present a story in which a  detective named T is hired by Mrs. Jonathan to investigate why her husband has been behaving in a peculiar fashion. T uses a movie camera to record Mr. Jonathan’s actions, and what we see purports to be the results. But, as a title points out, sometimes conditions made T’s filming impossible. What we see are scraps of scenes rather than coherent, continuous footage. The narrative deliberately depends extensively on lengthy intertitles and inserted documents, while the images suggest little in the way of narrative–as when repeated shots show Jonathan lingering on a bridge in the tourist town of Bruges while the intertitles list all the famous sights that he didn’t see (left).

detective named T is hired by Mrs. Jonathan to investigate why her husband has been behaving in a peculiar fashion. T uses a movie camera to record Mr. Jonathan’s actions, and what we see purports to be the results. But, as a title points out, sometimes conditions made T’s filming impossible. What we see are scraps of scenes rather than coherent, continuous footage. The narrative deliberately depends extensively on lengthy intertitles and inserted documents, while the images suggest little in the way of narrative–as when repeated shots show Jonathan lingering on a bridge in the tourist town of Bruges while the intertitles list all the famous sights that he didn’t see (left).

Histoire de détective flew in the face of all contemporary assumptions about the “cinematic” lying in images with as few intertitles as possible. It was audacious in ways that annoyed critics, and its considerable humor went right past most of them. Dekeukeleire apparently realized that his distinctive brand of experimentation had virtually no audience, and he turned to documentaries.

For some reason this program does not include his Witte Vlam (1930), a short Vertovian drama about a protest march broken up by police. It’s not Surrealistic, but no less so than some of the other films included here.

The two final films in the set are by directors who only made one film each. Both refer to Louis Feuillade’s  work, suggesting that his serials, though a decade old and more by the end of the 1920s, retained their hold on the Surrealist imagination.

work, suggesting that his serials, though a decade old and more by the end of the 1920s, retained their hold on the Surrealist imagination.

Henri d’Urself’s La perle (1929), is quite self-consciously a Surrealist work about a young man who keeps trying to buy and deliver a pearl necklace to his beloved, only to give it away to a lovely thief who tries to steal it from his hotel room. The thief is only one of several women lurking in the hotel corridors, all dressed in skin-tight body suits that recalls those worn by Musidora in her immortal role as villainess Irma Vep in Les Vampyrs. In true Surrealist fashion, although the hero enters a jewelry shop in a bustling street of a large city, he exits the building directly into country scene (right).

The last and latest of the films in the set is Ernst Moerman’s Monsieur Fantômas (1937), an intermittently  amusing homage to the super-villain of Feuillade’s 1913 serial. Traveling the globe in search of his true love, Fantômas (left, imitating his famous pose from the film’s posters) apparently commits a murder and is investigated by Juve, Feuillade’s clever but perpetually thwarted opponent. Filming on virtually no budget, Moerman set his action mainly on a beach and in an old cloister, thus allowing him to add some of the anti-religious touches so beloved of the Surrealists.

amusing homage to the super-villain of Feuillade’s 1913 serial. Traveling the globe in search of his true love, Fantômas (left, imitating his famous pose from the film’s posters) apparently commits a murder and is investigated by Juve, Feuillade’s clever but perpetually thwarted opponent. Filming on virtually no budget, Moerman set his action mainly on a beach and in an old cloister, thus allowing him to add some of the anti-religious touches so beloved of the Surrealists.

A bit of six-degrees-of-separation trivia: Fantômas is played by Jean Michel, the future father of French actor-singer Johnny Hallyday, who stars in Vengeance, the Hong Kong film by David’s friend Johnnie To that’s playing at Cannes this year.

The Belgian avant-garde cinema of this era is not a little backwater that merits a quick look only by specialists. Storck’s and particularly Dekeukeleire’s works are as sophisticated and challenging as almost anything that was going on in experimental filmmaking of the era, though the latter’s films were so idiosyncratic that they had no noticeable influence.

Back in 1979, when I learned about Dekeukeleire, I was so impressed that I sought to bring him some attention. I wrote an article, “(Re)Discovering Charles Dekeukeleire.” As the title suggests, Dekeukeleire hadn’t fallen into obscurity but had languished there from the beginning. Unfairly so, as I argued in the article, which was published in the Fall/Winter 1980-81 issue of the Millennium Film Journal. With this new DVD set making his and his colleagues work more accessible, I am inspired to revive my old article, which helps explain, I hope, some of what seems to me so original and daring about his early films, particularly Impatience and Histoire de detétective. The piece was written in the pre-digital age, and scanned .pdfs would probably be scarcely readable. So I plan to retype the thing and post it in the articles section of David’s website as soon as possible. [June 4: Done! Now available here.]

I hope that now devotees of animation and experimental cinema will seek out both these DVD sets. The Belgian one is in the PAL format, but without region coding. The Reiniger is also PAL, region 2 coding.

[May 23: Thanks to Harvey Deneroff for a correction concerning the American DVD of Prince Achmed.]

Pierced by poetry

DB here:

If I had a time machine, I’d zip over to Japan between 1924 and 1940. I’d trade a year of my life here and now for a year there and then.

Why? First, because the world I see in the movies of that period holds an irresistible fascination for me. I’d like to walk through Ginza, take a train to a spa, wander through Asakusa, have tea at the Imperial Hotel, hike around the temples of Kyoto. Second, if I could go back, I could see all the films I will never see—the lost Ozus and Mizoguchis, of course, but also the films we don’t even know are important.

For Japanese cinema in the 1920s and 1930s was one of the triumphs of world cinema. That era produced not only the two directors who are arguably the very greatest but also a host of talents you can’t really call “lesser.” The bench had depth in every position.

There are good reasons for this burst of genius. Quantity affects quality, but not the way snobs think: The more movies a country makes, the more good ones you’re likely to get. Although Japan had only a little more than half the US population, before 1940 it turned out about as many features as America did.In 1936, both countries released about 530 domestic productions.

The Japanese directors who started in the 1920s had, like Ford and Walsh in their salad days, to feed this audience. We tend to forget that even exalted figures entered the industry as high-volume producers. Mizoguchi averaged about ten releases per year in his first three years, Ozu about six. Everyone’s pace slowed with the coming of sound, but the sheer volume of movies pouring from studios big and small reminds us that young directors had plenty of opportunities to hone their skills.

Probably the most startling instance is Shimizu Hiroshi. In a career that ran from 1924 to 1959, he’s credited with directing 163 films. The earliest one of his that I’ve seen is Seven Seas Part I; this 1931 feature was his seventy-fifth. “Next year,” he remarked in 1935, “I’m going to make only three films the way the company wants me to, and in exchange I can make two films that I want. I want a little more time. I’m too busy right now.” As things turned out, he signed seven films in 1936.

The great bulk of his work, 139 titles, falls before 1946. Fewer than two dozen of these seem to survive. With only about 17% of the films available, we have to keep our generalizations modest. Who knows what we would find in Love-Crazed Blade (1924) or Flaming Sky (1927) or Duck Woman (1929)? Shimizu contributed to a series, the “Boss’s Son” or “Young Master” films, of which only his first, The Boss’s Son at College (1933) seems to survive. What would we find in The Boss’s Son’s Youthful Innocence (1935) or The Boss’s Son Is a Millionaire (1936)?

Luckily, we’ve wound up with some extraordinary movies, not a clunker among the ones I’ve seen. If only a smattering of 1930s and 1940s titles is available, we should be happy that it was this smattering. Shimizu had concerns in common with Naruse Mikio and Ozu Yasujiro, but he established his own world, a rich tone, and a simple but subtle visual idiom. Along the way, he created some of the most heart-rending films in world cinema.

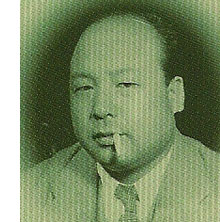

From the city to the spa

Shochiku talent at Izu hotspring, July 1928: Ozu Yasujiro (left), Shimizu Hiroshi (third from left), and screenwriters Fushimi Akira and Noda Kogo. Ozu and Shimizu were 23 years old.

Once more, all hail Criterion. TheTravels with Hiroshi Shimizu DVD collection released this spring includes Japanese Girls at the Harbor (1933), Mr. Thank You (1936), The Masseurs and a Woman (1938), and Ornamental Hairpin (1940). They were previously released on an expensive Japanese set (with English subtitles), but Criterion’s Eclipse series offers them at a more reasonable price, along with brief but helpful notes in English by Michael Koresky.

The collection’s title highlights the image of Shimizu that emerged in the 1980s. The films that struck Western critics then were typically shot outside the usual big cities (Tokyo, Kyoto, Osaka), in the mountains and seaside towns of the Izu peninsula. John Gillett’s 1988 National Film Theatre program, the first extensive survey of Shimizu’s work outside Japan, was entitled “Travelling Man.” Not only did Shimizu take his crew on the road, thanks to the expansion of the railway system, but he also exploited what became known as his signature technique: lengthy tracking shots down a road, following characters walking toward us.

Like Ozu, Shimizu worked in modern-day genres (gendai-geki), from slapstick comedies to college sports films. Most of what survives from before 1936 are social dramas of families, friendship, and fallen women. Seven Seas (1931-1932) deals with class conflicts, as a poor girl marries into a rich family and discovers that her husband is a bounder. Eclipse (1934) centers on the failure of young people from the countryside to succeed in a recession-hit Tokyo. The title of Hero of Tokyo (1935) is ironic, in that the stepson who abides by a mother held in disgrace by her other children, winds up destroying her last scrap of respectability. In Japanese Girls at the Harbor, two schoolgirls are driven apart by one’s passion for a young man. After a violent confrontation, she becomes a prostitute and her estranged friend winds up marrying him.

The Shochiku studio deliberately pursued a female market, and these tales of family intrigue and endlessly suffering mothers, wives, and daughters offer obvious figures of sympathy. Less predictably, the films simmer with criticism of modernizing Japan. They focus on the corruption of the upper classes, the collapse of traditions in the countryside, and the uprooting of the extended family.

Most significantly, Shimizu’s films indicate quite explicitly that Japan’s growing prosperity in the 1910s and 1920s was built on the backs of the rural poor, particularly the young women who flocked to textile mills, city shops, and brothels. Like many films of his contemporaries, Shimizu’s urban films mix sentiment and comedy with a harsh appraisal of social tendencies. I’d bet that we’d find both qualities in his Stekki garu (1929), a film apparently about the current craze for “walking stick girls,” women whom men hire to accompany them on strolls.

The manager Kido Shiro summed up the Shochiku spirit in the formula “smiles mixed with tears.” Ozu offered this blend in films like I Was Born, But… (1932) and Passing Fancy (1933), but there are precious few smiles in Shimizu’s surviving early thirties output. Then he took to the road.

In his films of travel Shimizu still offered social criticism, but he leavened it with off-center comedy. Indeed, he intensified Kido’s mandate: In Mr. Thank You, jaunty jazz and Latin American music accompany moments of sheer pathos. Now as well Shimizu’s intricate plotting, driven by the chance meetings and startling revelations of melodrama, could relax. Films like Mr. Thank You (1936), Star Athlete (1937), and The Masseurs and a Woman (1938) are expanded anecdotes, strings of situations that accumulate in casual fashion. Dramas emerge fleetingly, on the road or in hot-springs inns. The films tend to be brief, flowing toward abrupt, muted epiphanies in the manner of a short story. These movies make you ask whether 60-75 minutes might not be the ideal length for a movie.

In his films of travel Shimizu still offered social criticism, but he leavened it with off-center comedy. Indeed, he intensified Kido’s mandate: In Mr. Thank You, jaunty jazz and Latin American music accompany moments of sheer pathos. Now as well Shimizu’s intricate plotting, driven by the chance meetings and startling revelations of melodrama, could relax. Films like Mr. Thank You (1936), Star Athlete (1937), and The Masseurs and a Woman (1938) are expanded anecdotes, strings of situations that accumulate in casual fashion. Dramas emerge fleetingly, on the road or in hot-springs inns. The films tend to be brief, flowing toward abrupt, muted epiphanies in the manner of a short story. These movies make you ask whether 60-75 minutes might not be the ideal length for a movie.

The easygoing plots echo the movies’ production process. Shimizu wasn’t an obsessive planner. Whereas Ozu sketched every shot and checked the composition through the camera, Shimizu wrote minimal screenplays and seldom budged from his chair, even when the camera was traveling. He shot quickly, making up dialogue as needed and giving actors the most cursory direction imaginable. (“Run.”) Yet this wasn’t a high-pressure situation. Some days, uncertain about what to do, Shimizu would shut down the shoot and take people swimming.

Tears and smiles

I don’t want to leave the impression that Shimizu was careless; below I’ll try to show that he set himself some powerful storytelling problems. And his relaxed manner yielded a unique mixture of traditional drama and more vagrant appeals. Take Mr. Thank You, my pick for the crown of the Criterion set.

It’s a road movie, although the trip runs only twenty miles. A rickety bus winds through the mountains around the Kawazu region of Izu, an area of hot springs and tiny villages. The handsome, kindly young driver is known only as Mr. Thank You (Arigato-san) because whenever he forces walkers off the road he waves and calls his thanks. He has earned the devotion of people in the region, who entrust him with messages and duties on their behalf. On this particular day, his bus is carrying a stuffy real-estate agent; a wisecracking moga (modern girl); and a young girl whose mother is accompanying her to Tokyo, where she is to be sold into prostitution. Other passengers—wedding guests, lonely old men—get on and off in the course of the trip.

The bus stops often, and the encounters give us vignettes of the deteriorating life of the countryside. We hear of the magic attractions of Tokyo, reported by a prosperous woman about to get married. A Korean woman working on road construction asks Mr. Thank You to visit her parents’ grave, reminding us that this oppressed minority has contributed its sweat to the new Japan. Counterbalancing these stabs of pure feeling are simple running gags, such as one involving rude auto drivers who insist on passing the bus. And across the trip, the fate of the girl draws ever closer.

The moga (evidently a hooker) becomes our raisonneur, commenting on everyone’s motives, denouncing hypocrisies, flirting with Mr. Thank You, and eventually offering advice on how to save a life. Shimizu fills his film with talk and music, but in quieter moments imagery takes over: shimmering valleys below zigzag mountain roads, tunnels and forests and glimpses of steep paths along which road workers trudge. Within the bus, point-of-view is channeled fluidly. At one point we watch the moga watching the driver watching the girl. The climax of the action is simply omitted, yielding a quick, upbeat coda. In sum, Mr. Thank You radiates the cheerful, compassionate resilience of its namesake.

The mixture of tears and smiles is present as well in The Masseurs and a Woman. In Japan, blind people traditionally have taken up the trade of massage. So we start on the road, tracking back from two masseurs feeling their way along. The gags start immediately, with one praising the view, but poignancy comes just as fast: “It’s a great feeling to pass people who can see.” And again a gag undercuts it: “I bumped into some horses and dogs, though.” Shimizu sets up his brand of incidental suspense—uncertainty about matters of no dramatic moment—when the two begin to guess how many people are advancing to them. Eight and a half? We wait and, when the shot comes, we quickly count to check.

This seesawing between humor and pathos defines the tone of the whole film. Once the men arrive at the inn, we’re introduced to several guests, and a notably piecemeal plot: an aborted romance, a mysterious theft, and the attraction of one masseur toward an enigmatic woman. On the light side, students who tease the blind get extreme massage makeovers, reducing them to hobbling the next morning in a parody of the blind men’s halting gait. Shimizu assures their humiliation by head-on shots of modern girls hiking into the midst of them. And of course the blind-guy jokes multiply when several masseurs are trying to navigate a room or a street. Again, the film is over before you know it, leaving that Shimizu tang of chance encounters and what-if possibilities.

Blind masseurs play a minor role in another spa movie, Ornamental Hairpin (1941), but an almost-begun romance is there as well. Two women, Okiku and Emi, pass through an inn, and after they’ve left Emi’s hairpin jabs a young soldier’s foot. He will spend the rest of the story recovering his ability to walk. Emi returns to the inn and joins its summer guests: a cranky professor, a grandfather and his two pesky grandsons, and a married couple.

“Pierced by poetry,” says Nanmura casually about his wound, but the professor extrapolates on the phrase, trying to weave a romantic plot out of the accident. Shimizu declines to share the fantasy. A bit like Tati’s M. Hulot’s Holiday, the film is threaded with mundane vacation routines that become running gags, overwhelming what we expect to shape up as a courtship.

Bronzing in the sun and helping Nanmura recover his ability to walk, Emi comes to believe that she has found happiness. She has fled Tokyo and wants to start fresh. But her past, either as wife or kept woman, is kept vague. In two remarkable scenes, one a phone conversation and the other a dialogue with Okiku, her situation is sketched. We start to fear that her man will even come looking for her.

But these bits of conventional plotting are drop away among prolonged scenes of spa gossip and lazy pastimes. The most suspenseful sequences are devoted to Nanmura’s gradual recovery—a sort of deadline, since when he walks again, he will leave. If ever a climax refused to arrive, it’s during the last ten minutes or so of Ornamental Hairpin. The moments of pathos or conflict we would ordinarily see are skipped over, and the surroundings of “minor” scenes become infused with regret.

Shimizu’s ramblings through Izu didn’t lead him to abandon his probing of urban anomie, as we can see in Forget Love for Now (1937). (This must be one of the great Anglicized Japanese titles. I rank it with Blackmail Is My Life and Go, Go, Second-Time Virgin.) And at the same time he consolidated that talent for which he was best known in his lifetime: the exploration of childhood. Children in the Wind (1937), Four Seasons of Children (1939), and Introspection Tower (1941) offer unsentimental portrayal of boys’ rituals and their tenacity in the face of hardship. Shimizu founded an orphanage after the war, and he employed some of his charges in postwar films like Children of the Beehive (1948). Shochiku’s second boxed set, also with English subtitles, gives us the first three I’ve mentioned, plus the schoolteacher drama Nobuko (1940).

East meets West, and North meets South

Ornamental Hairpin.

Japanese film studios differed from their American counterparts in encouraging directors to cultivate individual styles. Kido supposedly fired Naruse by saying, “We don’t need two Ozus.” While Shimizu is not as daring or meticulous a stylist as Ozu, he managed to cultivate a visual approach that, however straightforward, was capable of delicate refinements.

In general, the Shimizus we have conform to trends in Japanese films of his period. His silent films from the years 1931-1935 adhere broadly to the Shochiku house style, using plenty of cuts and single framings of individuals. Most of the surviving silents have average shot lengths between 5 and 6 seconds, completely normal for both Japanese and US silent movies.

More remarkable is the number of dialogue titles, which make up between 24% and 44% of all shots. This would be exceptional for an American film of the 1920s. Other Japanese films, particularly Mizoguchi’s, are heavy with intertitles, but Shimizu took the trend somewhat farther. The preponderance of dialogue titles may owe something to the presence of both American and a few Japanese talking pictures at the time, which justified more spoken lines. In addition, at this period the influence of the benshi, the vocal accompanist to silent films, was waning, and the movies were becoming more self-sufficient in their narration. The hundreds of titles flashing by in Shimizu’s films would specify the scene’s action and curb the benshi’s urge to improvise.

Shimizu’s silent films that survive also contain several instances of a technique I’ve called the “dissolve in place.” The camera setup remains fixed, but one or more dissolves convey the changes in the space across a period of time. It’s commonly used to show long periods; in A Hero of Tokyo, the family’s growing poverty is shown through dissolves that gradually remove the furniture they’re been forced to sell. The technique can be seen in American silent films, a major source for most Japanese directors. Here’s a lovely example from Frank Borzage’s Lucky Star (1929), as the partly paralyzed Tim struggles to climb onto his crutches.

Shimizu often goes a little further by matching the figures precisely across a dissolve. In The Boss’s Son at College, the hero comes home but then sneaks out in his bare feet, and the dissolves concentrate on the reversal of movement, first upstairs, then down.

Again, this device was used by other Japanese directors, even Ozu in some early works, but Shimizu seems to have clung to it longer than most.

In general, Shimizu’s silent films don’t borrow his pal Ozu’s more idiosyncratic techniques. Shimizu doesn’t employ intermediate spaces to link scenes, or create elaborately disruptive transitions, or embed characters in 360-degree shooting space. Sometimes he offers mismatched eyelines in reverse shots, but these don’t usually cultivate the graphically exact alignment we find in Ozu’s editing. Still, Shimizu does often construct a scene’s space in a distinctive way.

For one thing, he will stage many scenes in long shot or even extreme long shot. Within that sort of shot, he’s often drawn to deep perspective, often with a central vanishing point. This is most apparent as a visual motif throughout The Boss’s Son at College.

More interestingly, his fascination with perpendicular depth governs staging and cutting. Imagine a line stretched straight out from the camera lens. By 1935 this lens axis has become Shimizu’s lifeline, his equivalent of the surveyor’s level. Rather than filling the foreground with a big figure or a face or prop, and rather than spreading his depth items wide across the background, he will pack the most important people along the center axis, like crystals growing out from a string. Here are instances from Japanese Girls at the Harbor and Eclipse.

Shimizu’s co-workers have testified that he cared little for the 180-degree rule. Like many Japanese filmmakers, he played fast and loose with it. Instead of an axis running between the characters, he was more concerned with the axis of the lens itself. He often respects that by cutting from one shot to a point (along the axis) 180 degrees opposite.

He also respects the lens axis by cutting straight in and out. In Hero of Tokyo, the mother learns that her husband has pulled a swindle and fled; then the officials leave her alone with her children. Shimizu simply enlarges and shrinks her systematically along the axis. He takes us to the other side of the group for the climax, when her birth children pull away from her stepson. We see no other camera positions in the scene.

This patterning is less abrasive than it might appear because intertitles are sandwiched in among these shots. It’s an intriguing strategy for thrifty filmmaking, since it requires only a rudimentary set, but it also offers a simple way to inflect the drama. Similar axial cuts, though not cushioned by titles, can be found in the shooting scene of Japanese Girls at the Harbor (which may owe something to French and Soviet cutting experiments of the period).

The depth stretching out from the camera lens is crosscut by another plane, perpendicular to it. This plane is often a patterned surface—windows, grillwork, a bedstead. Again, instead of Mizoguchi’s or Ozu’s angular foregrounds, we have an east-west axis slicing through the shot. The frames become boxes, and the characters play out their dramas within the cells of a grid, as in Seven Seas Part II and Japanese Girls at the Port.

Here again, Shimizu is relying on a device that other directors were using at the time. Many compositions of the 1930s play peekaboo with characters and setting. Here’s a flamboyant example from First Steps Ashore (Shimazu Yasujiro, 1932).

So instead of defining space through exaggerated foregrounds, plunging diagonals, or curvilinear edges, Shimizu goes Cartesian on us. His most distinctive layouts rely on two dimensions, one running straight into depth, the other running left to right. The result is a discreet, foursquare style well-suited to concise storytelling (and presumably, to turning out films quickly). Shimizu’s peers indulged in flashier shots, but his persistent choices yield a quiet variant of that continuity system that was already the lingua franca of world cinema.

Hitting the road

What about the sound films? Many Shimizu films still rely on distant planes of depth, as in this shot from Children of the Wind, when, after the father’s arrest, the boys’ buddies arrive at a far-off vantage point.

Interiors will sometimes be given the axial-cutting treatment, as in this passage from Ornamental Hairpin.

And now the crosscut horizontal plane often gets actualized as rooms gliding by the lens in lateral tracking shots. But in general, interior scenes in this 1941 film aren’t as strictly organized as in the silent films. This corresponds to a general move toward more orthodox technique in Japanese films of the period.

Something more original happens in the outdoor traveling shots. Now Shimizu’s beloved camera axis finds tangible expression in the highway. His much-vaunted tracking shots up and down the road translate the silent films’ axial depth into forward and backward movement, and characters, again organized in relation to the axis, are presented with a new simplicity and directness. Rather than being a one-off device, the road shots seem to be a development of the Cartesian coordinates that Shimizu has experimented with in the interior spaces of his silent films.

Star Athlete offers some remarkable examples of the push-pull effects built around the axis—tracking back from advancing characters, or tracking toward retreating ones. But Shimizu’s most thoroughgoing exploration of the camera axis in transit takes place in Mr. Thank You. The first thirteen shots lay out a stylistic matrix, with variants dropped in to prepare us for more compact expression later.

Shot 1: A long shot of the bus approaching.

Shots 2-4: We get the bus’s point of view of the road, with road workers in view; head-on shot of the driver calling “Thank you!” as the men step back; and the bus’s pov of the road receding, with the workers resuming. Dissolve to:

Shots 5-7: Bus’s pov of horsecart ahead; reverse angle of driver calling, “Thank you!”; bus’s pov of cart receding. Dissolve to:

Shots 8-9: Bus’s pov of men toting wood; we hear, “Thank you!” as we dissolve to bus’s pov of men receding. Dissolve to:

Shots 10-11: Bus’s pov of women carrying bundles; we hear, “Thank you!” as we dissolve to bus’s pov of women receding. Dissolve to:

Shot 12: Bus’s pov of chickens in road. They scatter as we get closer.

Shot 13: Long shot of bus going into the distance as we hear, “Thank you!”

The cycles move from three-shot clusters to two-shot clusters to a single shot, and a gag at that. (This driver even thanks poultry for traffic courtesy.) As another touch, Shimizu’s prized dissolves-in-place are recalled when the pedestrians approached from the back transform themselves into figures dwindling into the distance.

The same insistence on rectilinear framing takes place on the bus. Using 180-degree reversals, Shimizu creates a remarkable variety of shot scales in the cramped space of a real vehicle, always obeying his self-imposed geometry–facing either forward or backward.

As the trip gains emotional intensity, Shimizu will vary his treatment of these principles. For example, the middle section’s emphasis on forward movement will be counterbalanced near the end by a string of shots of passengers already off the bus, passing into the distance as we roll away.

In Shimizu, compact storytelling is matched by a pictorial strictness that doesn’t seem forced or stiff. After all, people do tend to line up to face one another in depth, and roads and buses do seem to run in two directions. Poetry in language demands strictures of meter, rhythm, rime, and the like, for these can pressurize expressive energies. Shimizu’s films present a disciplined lyricism: powerfully oblique emotions are shaped by simple but rich techniques of storytelling and style.

Most of my information about Shimizu’s work habits comes from essays and interviews in Shimizu Hiroshi: 101st Anniversary, ed. Li Cheuk-to (Hong Kong: Hong Kong International Film Festival, 2004). For more on Shimizu’s surviving silent films, see William Drew’s penetrating essay in Midnight Eye. Alexander Jacoby offers a sympathetic career overview atSenses of Cinema. For a filmography, see Jacoby’s A Critical Handbook of Japanese Film Directors: From the Silent Era to the Present Day Stone Bridge, 2008). Isolde Standish reviews Shochiku’s studio policies in Chapter 1 of her A New History of Japanese Cinema: A Century of Narrative Film (Continuum, 2005).

Noël Burch was one of the first Western writers to appreciate Shimizu’s artistry. His indispensible 1979 book To the Distant Observer: Form and Meaning in the Japanese Cinema is available in its entirety here. The Shimizu chapter, concentrating mainly on Star Athlete, starts here. I offer discussions of stylistic trends in Japanese cinema in Ozu and the Poetics of Cinema (Princeton University Press, 1988), available in toto here, and in two essays in Poetics of Cinema (Routledge, 2008), 337-395.

You can find passionate conversations about Shimizu and the release of these DVDs at the Criterion Forum. See especially the comments of Michael Kerpan.

Take my film, please

Kristin here–

As I mentioned in our main entry about Ebertfest, Nina Paley’s animated feature, Sita Sings the Blues, was one of the highlights of the festival. Afterward I had the privilege of moderating the onstage discussion with the director and University of Illinois film professor Richard Leskovsky, who has a special interest in animation.

Sita has not had a regular theatrical release, though Nina has made it available to theaters, festivals, and everyone with access to a high-speed internet link-up. She gives it for free to anyone who wants it, believing that people who see it will pass the word along and that as the film becomes more well-known, it will become more valuable as well. Income should flow in. Nina is confident, some might say cocky about this. The thing is, she may be right. Sita is a terrific film, and I can well imagine a ground-swell of interest gradually building. Indeed, it’s happening already. Here I am, blogging about it, and others are as well. Non-bloggers are emailing their friends. Festivals have booked it up to the end of this year and beyond.

Roger Ebert found Sita early on, and his program notes were also his online review, which begins:

I got a DVD in the mail, an animated film titled “Sita Sings the Blues.” It was a version of the epic Indian tale of Ramayana set to the 1920’s jazz vocals of Annette Hanshaw. Uh, huh. I carefully filed it with other movies I will watch when they introduce the 8-day week. Then I was told I must see it.

I began. I was enchanted. I was swept away. I was smiling from one end of the film to the other. It is astonishingly original. It brings together four entirely separate elements and combines them into a great whimsical chord.

The four elements are: a sketchily animated account of the breakup of Nina’s marriage; the tale of Rama and Sita from the Indian epic, the Ramayana; musical numbers that all borrow recordings of Ms Hanshaw; and three shadow-puppet narrators who try, not always successfully, to recall the details of the Ramayana and its background history. As Roger says, somehow all this achieves complete unity.

The timing of the Ebertfest screening was fortuitous. Within the next few weeks, the DVD release is due. Of course, you can already watch it online and/or burn your own DVD. But for those who can’t or don’t want to, you can buy the DVD package, complete with what is described on the film’s website as a predownloaded copy of the film.

As Roger’s review says, Nina is a hometown girl. She started out doing comic strips and then made some  animated shorts before progressing to Sita, her first feature. Her father taught at the University of Illinois. Her mother was an administrator there. Both have supported her in the making and distribution of Sita, and both were present throughout the festival.

animated shorts before progressing to Sita, her first feature. Her father taught at the University of Illinois. Her mother was an administrator there. Both have supported her in the making and distribution of Sita, and both were present throughout the festival.

Here’s a transcript of our conversation (that’s Nina at the far left, Richard, and me). Applause, laughter, and a fast-talking film director at times defeated my efforts to catch every word of my recording, so some details have been lost.

KT: I know you want to talk about how you’ve been getting the film out to the public, but I’d like to start off by talking about the film itself, which is fascinating. I think we can start with the computer animation. A lot of people think that you were pushing a lot of buttons and somehow the computer was generating the images. But obviously you were generating them yourself by painting and collage and so forth. Could you just start with the process of what you did before you put this material into the computer and then what you did afterwards?

NP: Well, there are a whole bunch of different styles and techniques used in the film. The style of the musical numbers, actually I drew that in Flash using a lot of really simple tools, so the perfect circles have a smoothness that you don’t get by hand. By the way, I want to mention that what you saw was not 35mm. You saw HD-cam, and there are actually 35mm prints of this, and seeing it here was very strange. It was unusually solid, rock solid, a little bit troublingly solid, although that is the ideal that film technology has been striving for. But 35mm prints have all these scratches and splices, and grain and a kind of warmth that moves around, which is almost like a kind of very desirable filter that really warms up the film. So watching it in 35mm is different. I was noticing how computery it looked on the HD projection at this particular size, because I was looking for imperfections that simply weren’t there.

But anyway, yeah, I did some paintings on parchment paper. To me, some things were simple, because I only had me working on the animation, and I used as many computer shortcuts as I possibly could. Most of the technique was what’s called “cut-outs,” so I made pieces of things, moved them around, and the computer does what’s called “tweening.” [i.e., in-betweening, filling in the frames between key points] There’s a little bit of full animation in there. It would take a long time to say everything that I did.

KT: Yeah, but every bit of that visual material was something that you put into the computer in some fashion, so that-

NP: The computer didn’t draw it, that’s for sure. I drew it, whether I started with paper or drawing on a little [digital] graphics tablet or eventually I got what’s called a Cintiq, which is a monitor you can draw on. You can draw straight into a program through the monitor, and so what’s on the monitor-it tricks you into thinking you’re actually drawing on the screen, but it went through both my hand and the computer.

KT: Is this the kind of thing you teach? Do your students learn how to do this kind of animation?

NP: No. I’d love to teach this. A lot of the students are just not [inaudible]. So right now I’m teaching visual storytelling, which is a much more basic class, and I taught something called “classic film and video” for a while at Parsons [School of Design]. I actually really like to teach artists. I’m teaching people who already know what they want to say and already have a voice and just need a little bit of technical-it’s slightly faster if they ask me rather than reading a manual. I learned by reading manuals.

RL: It struck me that you’re a woman artist making an animated feature, and actually one of the very first animated features, done ten years before Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, was Lotte Reiniger’s The Adventures of Prince Ahmed, which also deals with Eastern myths. You actually did a little bit of the cut-out animation there, too, with the shadow-puppets. That brings a nice circularity-

NP: Well, hopefully this isn’t the last one!

KT: Was that the silent film that you referred to in your film?

NP: I still haven’t seen that film. First of all, everything has influenced me, because everything influences everything else. Culture [inaudible] language, so there’s a language of cell phones, a language of animation that comes from every piece of animation that’s been shared ever. So even if I haven’t been directly influenced by something, I haven’t seen the actual film, I will have been indirectly influenced by it simply keeping my eyes open.

RL: All the Annette Hanshaw songs are accompanied with the Flash animation, but it looked like there was a couple of different styles of Indian art represented there, from different periods. Tell us a little bit about what the choice was.

NP: The Ramayana is thousands of years old, and it also covers an enormous chunk of geography. It’s very popular not just in India but also in Cambodia, Thailand, Polynesia, Indonesia, this huge swath of South and Southeast Asia-parts of China. So there’s just this enormous range of art styles that have come up around it, and the styles I used in the film were influenced by just a tiny, tiny sample of that. Obviously shadow puppets. The designs were derived from puppets from Indonesia, Korea, Thailand, Malaysia, and also India. There’s a whole slew of paintings. There’s lots of Ramayana paintings that were actually commissioned by Muslim [inaudible] who had money. There were collages of these traditional arts. Everything went into the hopper, all going into my head Everything goes in there, grinds up, and comes out.

KT: Traditionally in animation the entire soundtrack is done first, which is not the way it’s done in regular live-action filmmaking, but of course it’s virtually impossible to synchronize cartoons if you have someone doing the voices after the animation is done. So could you tell us a little about the soundtrack and how much of it you had ready by the time you started the visuals?

NP: Well, I should say, the whole production, it’s not like I had everything ready when I started the visuals. The way you’re supposed to make a film, first you’re supposed to write a treatment, and then you’re supposed to write a script, and then you’re supposed to, if it’s animation, have everything designed and do breakdowns and storyboards and this and that, and then at the very end you animate it.

I didn’t have to do that, because it was just me working and it was with a computer. So I came up with things as I was going along. The whole structure of the story was there, because the Ramayana is this very well-established story that’s been told billions of times. I knew that story. I also had the songs, so the first thing that I synchronized and edited was the songs. As I was working on those, I was figuring out how the rest of the film was going to come together. The [inaudible] part of the film was the three narrators, who were just friends of mine who I convinced to go into a recording studio, and I asked some questions about the Ramayana. They were all very busy and went, “Oh, I should have read more before.” The conversation that they had was actually quite typical, because I had so many conversations with so many Indians, who-it was just uncanny, they really captured the twenty-first century zeitgeist of Ramayana, I guess.

RL: That intermission was a bit daring.

NP: I should mention that the 35mm print, depending on where you see it, it has surround sound and the HD only has stereo. If you see it on 35mm, depending on what speaker you’re near, you’ll hear different complete conversations coming out of each. Some of those conversations are extremely funny. I recommend the left rear speaker. There will be Will Franken, who’s a distribution executive, talking about unsellable the film is. And there are people on the front right speaking Hindi. I think they’re saying, “I thought this was a children’s film.”

So, yes, intermission. Old American musicals had intermissions. I was watching some of them while I was working on the film, and sure enough, two-thirds of the way through, intermission comes up. Bollywood films still have intermissions-a three- or four-hour-long Bollywood film has a little gap. So it was a tribute to both old American musical films and all Bollywood films. When I showed the film in Livingston, New Jersey to an audience of primarily Indian-Americans, during intermission they just left for 15 minutes. And they missed my favorite part of the film, which is the part that comes a minute after the intermission.

Nina’s favorite part, shortly after the intermission

KT: I can second that statement about the 35mm, because I was lucky enough to see this film three weeks ago in 35mm at the Wisconsin Film Festival, and it’s a different experience. I’ve enjoyed both of them, but I think there are definite advantages to 35.

It’s actually much easier for most people to see this film on a computer screen or television, because you chose a very unusual way to disseminate the film to the public. Can you talk a little about that?

NP: Why, yes, I can! You can see this film for free online if you go to sitasingstheblues.com and follow a variety of links and get the film. You can get everything from a streaming version from New York Public Television to a 200 gigabyte file from which you can make your own 35mm print if you have $30,000 to download it. Briefly, every file I have for the film is either online now or it’s going to go online. It’s a completely decentralized distribution model. People have compared it to Radiohead’s [inaudible] English model [for their “In Rainbows” album, 2007], but that’s different, because that relied on a single, central location where you got the audio, and it was tracked. It was simply what you decided to pay.

Mine is totally decentralized. I shouldn’t even call it “mine” anymore. It’s yours. This film belongs to you and everybody else in the world. The audience, you and the rest of the world is actually the distributor of the film. So I’m not maintaining a server or host or anything like that. Everyone else is. We put it on archive.org, a fabulous website, and encourage people to BitTorrent it and share it. That’s what’s happening, and we hope people do it more. There’s also broadcast versions, which you can download. If anyone here is from a television station, you can broadcast this for free.

Which begs the question, why is Nina Paley giving her work away for free? Doesn’t she want to get money? The answer is yes, I want to get money, and I believe that I will get money. I think I am getting money from this, because the more people share the film, the more valuable the film becomes. I have told people after screenings that they can get the film for free online, but I have some DVDs which I sell for twenty bucks, and here for twenty-five bucks-the Virginia is still remodeling, so this is for the Virginia.

I should also mention regarding DVDs that we, my mom-Oh, I should mention my mom! Sorry, I[inaudible] my parents, of course, who gave me the gift of life and all that, but my mom, who gave Sita Sings the Blues the gift of being its festival-relations manager, which is a huge, huge job. For those who don’t know, my mom was the main administrator of the math department of the University of Illinois and is a spreadsheet master and business-communications master and stuff like that and has been just essential to the film having such a successful festival life. So, thank you, mom! [Applause]

Anyway, I have made thousands of festival screeners so that festivals will have something to preview, and we’re down to the last 35, or at least we were this morning, and we handed them to the people in the Virginia, and that’s it for DVDs until a few weeks from now I’ll have the new purchasable DVD edition available.

RL: Will there be special features?

NP: Because the film is free, people can subtitle it freely, and the new one will have some subtitles. There’s gonna be more subtitles online. It’s been translated into French and Hebrew and Spanish and Italian and pirate. [applause and laugher covers a stretch of speech] The thing is, the film is now half-way. It will just continue growing, so whatever the DVD is, it’s just snatched off the stuff we have as of this week. So it’ll be the film, it’ll be a bonus feature called Fetch, a film I made, it’ll be some subtitles, I think there’ll be a couple different audio options.

It’ll be a very nice package, because basically what I’m selling is packaging for the film. If you have a computer, you’ve got your own packaging. You just download it. But many people just the same want an actual printed package. There’ll be two editions. There’s the artist’s edition, a limited edition of 4,999 DVDs, because for every five thousand DVDs I sell, I have to pay the licensers more money. You may think that’s too bad, and it’s OK if the other DVD distributors pay the licensers more money, but I [inaudible] paid $5,000 in order to decriminalize the film, so that I wouldn’t go to jail.

Jean Paley from the audience: Fifty thousand!

NP: Fifty thousand, yeah. Fifty thousand dollars is enough.

KT: Which is for the song rights.

NP: Yes. Those old songs. I cannot thank Roger enough for writing about this film. Also, after he wrote about it on his blog, my colleague, a professor of copyright law here, said, “Does he know about the copyright issue of the songs?” The film uses old songs that were written and performed in the late 1920s. Had they been from 1923, they would be in public domain now. When they were written, they were supposed to be in public domain in the 1980s, but there have been these continuous, retroactive copyright extensions, so they may never enter the public domain.

NP: Yes. Those old songs. I cannot thank Roger enough for writing about this film. Also, after he wrote about it on his blog, my colleague, a professor of copyright law here, said, “Does he know about the copyright issue of the songs?” The film uses old songs that were written and performed in the late 1920s. Had they been from 1923, they would be in public domain now. When they were written, they were supposed to be in public domain in the 1980s, but there have been these continuous, retroactive copyright extensions, so they may never enter the public domain.