Cinema in the world’s happiest place

Thursday | July 2, 2009 open printable version

open printable version

Bust of Carl Theodor Dreyer in the Dagmar Bio, the film theatre he once managed.

DB here:

Denmark was the first foreign country I ever visited. Having never been to Canada or Mexico, I took off in the early summer of 1970. Technically, I touched down in Reykjavik first because I was flying Icelandic Airlines, the Ryanair of its day. You flew Icelandic to get to Europe as cheaply as possible. Although a few people got off at Reykjavik, most of us sat patiently on the tarmac before heading off to Copenhagen.

Ever since that summer, when blinding light invaded my basement room at 4:00 AM, I’ve had a soft spot for Denmark. Ib Monty, then head of the Danish Film Archive, kindly screened for me all the Dreyers I hadn’t seen, and in spare moments I learned the joys of Copenhagen’s canals and restaurants. Six years later I would spend nearly another whole summer there watching the same Dreyer films on a flatbed viewer in the archive vaults, a somewhat renovated army fort. Many visits later, including a couple to the charming city of Aarhus, I’m still a fan of the Danes. They manage to be modest yet accomplished, hard-working yet hard-partying. They put cultural figures like composer Carl Nielsen on their currency. We’re told that they are the happiest people in the world. I don’t doubt it.

So it was with special pleasure that I returned to Copenhagen for two weeks in June. The second week was consumed by a day of talks and seminars at the University of Copenhagen and then by the convention of the Society for Cognitive Studies of the Moving Image. I’ve given two long-winded previews of the latter event, and I hope to have more coverage of it in a later entry. Today, a smorgasbord of other things Danish–without, alas, mention of H. C. Andersen, Vilhelm Hammershøi, or Victor Borge.

Chaos reigns, more or less

The organizers of our SCSMI event pulled off a coup: Not only were we shown Antichrist in Asta, one of the Danish Film Institute‘s fine theatres, but along came Lars von Trier to spend an hour talking about it afterward.

The film struck me as mid-level von Trier, not as good as The Idiots, The Kingdom, Dancer in the Dark, and The Boss of It All (though others would call me out for admiring this last). It lacks the element of game-playing that I enjoy in what von Trier calls his “mathematical” works, most famously The Five Obstructions. Instead, Antichrist provides perhaps the most unadulterated surge of emotion and mystical/ mythical implication to be found in all his work. It tries to be an intellectual horror film somewhat in the David Lynch mode, with a plaintive, roiling soundtrack and unearthly visions, including a fox snarling, “Chaos reigns!”

I was surprised that the elements so sensationalized by the press are pretty brief; snip out four brief shots and you’d have a ferocious but much less controversial movie. It starts as your basic two-handed psychodrama, with a couple tearing at each other. As in those other duologues Strindberg’s The Stronger and Bergman’s Persona, the film presents a fluctuating power struggle–the man trying to rule through cool rationality, the woman tapping depths of grief and repressed anger.

Yet the film goes beyond psychodrama into realms of history and myth. The grieving mother rises into demonic fury by getting in touch with witchcraft, the subject of her unfinished university thesis. Antichrist could thus be read as an exercise in misogyny or as a celebration of woman’s primal energies. (For what it’s worth, several women in our audience said they liked the film a lot.) Of course the whole thing looks very fine, with a stylized black-and-white prologue (some shots taken at 1000 frames per second), and the rest rendered in that dodging, wandering camera style von Trier and the brilliant cinematographer Antony Dod Mantle have made their own.

The entire Q & A with von Trier, moderated by Peter Schepelern, is available as an audio file on the SCSMI conference website, perhaps to be followed by a video record. Some excerpts:

Von Trier explained that the film came out of a period of prolonged depression. “I used this project to get out of bed [every day].” Yet it’s less personal than his other works, he thinks, because it lacks his usual interest in rules, obstacles, and formal play–“a little more messy.” And he feels that by not operating the camera, he lost some intimacy with actors.

Von Trier explained that the film came out of a period of prolonged depression. “I used this project to get out of bed [every day].” Yet it’s less personal than his other works, he thinks, because it lacks his usual interest in rules, obstacles, and formal play–“a little more messy.” And he feels that by not operating the camera, he lost some intimacy with actors.

The Antichrist project seems to have brought out a mystical side of von Trier that hasn’t been so prominent in his public image. Years ago he conceived a film in which Satan created the earth, but that dissolved. Certain elements of the film, especially the emblematic forest creatures–blackbird, deer, and fox–come from his interest in shamanism. He has, he claims, traveled in alternative worlds with animal guides. “Never trust the first fox you meet.”

Is it a horror film? At least it has sources in the genre. Uncharacteristically, von Trier prepared for the project by revisiting not only classic horror films he admired, The Exorcist, The Shining, and Carrie, but also The Ring and Dark Water. He was particularly influenced in his youth by Altered States, another venture into “fantasy travels.”

He commented on how his free-camera technique imposed certain constraints in sound work. If you execute a “time cut”–that is, cutting directly to a new scene starting on a shot of a character–you must alter the sound somehow; otherwise the audience is likely to think that the action is continuous. This got me thinking about how The Boss of It All violated that convention, when each continuity cut actually yields a different sound ambience because each of the many cameras is miked separately.

Why is the film dedicated to Tarkovsky? “It was a way of getting rid of psychology.”

“I do not work with the audience in mind. I make films I would like to see myself.”

The Last is not least

Last Friday night the filmmaking program at the University of Copenhagen gave out its student film awards. The crowd was large and boisterous, the atmosphere festive and tipsy. I was honored to present the prize for the best fiction film, which went to desidst (punning on De sidst, “The Last”). The three winning filmmakers, pictured above, were Sissel Marie tonn-Petersen, Niels Holst-Jensen, and Toke Westmark Steensen.

Before I read the result, though, I was confronted with some damaging evidence in a copy of Film History: An Introduction.

Peaking in the 1910s

During my first week in Copenhagen, I was viewing Danish films from 1911 to 1915. As long-time readers of this blog know, I’m fascinated by the films of the 1910s, and Denmark boasts some of the most sophisticated works of the time. Thomas Christensen and Mikael Brae of the Danish Film Archive kindly let me watch several films, mostly from the once-mighty Nordisk film company.

The most remarkable films I saw were Ekspeditricen (1911), Dyrekøbt Aere (“Hard-Won Honor,” 1911), and Under Blinkfyrets Straaler (“Under the Beam of the Lighthouse,” 1913). All three of these offer sophisticated examples of the dominant storytelling technique of that period, what has been called the tableau style.

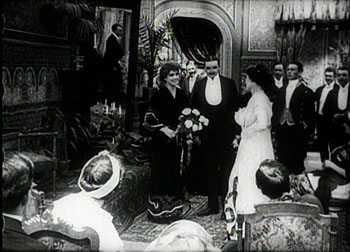

I can’t offer any visual analyses here, as I don’t have frame stills available in digital form, but here’s an example of the kind of thing I’m studying, taken from August Blom’s The Ballet Dancer (1911). Camilla (Asta Nielsen) has been seduced by Jean, a man-about-town, and she has come to sing for a society soirée at which Jean is present. But Jean is also carrying on an affair with the host’s wife.

The scene starts with the host Simon walking with his wife to the middle of the salon. Note the mirror in the upper area of the frame, just left of center.

She goes out frame right, and the host welcomes Camilla, bringing her to the central zone of the shot.

The hostess returns from off right to greet Camilla. Now we can see Camilla’s lover Jean in the mirror.

The hostess leaves the frame again, her husband settles into a chair, and Camilla starts to sing. But in the mirror we can see Jean bending over to kiss the hostess.

Soon Camilla notices Jean’s flirtation, and he straightens up.

Camilla interrupts her song, shouting and thrusting an accusing finger at the couple across the room.

I especially like the way in which Camilla’s finger points both at the offscreen couple and directly at her guilty lover’s reflection. If we haven’t noticed Jean’s infidelity yet, we certainly should now.

Today the same scene would be handled with lots of cutting and point-of-view framings, but the mirror allows Blom to pack a single long shot with simultaneous actions. (Mirrors were something of a signature device in Danish films of the period.) It’s a nice example of Charles Barr’s notion of gradation of emphasis, a principle that was at the heart of the intricate, sometimes exquisite ensemble staging we find so often in the 1910s.

Far from being a static, “theatrical” rendering of the action, the tableau technique looks forward to the deep-space stagings we associate with Welles and Wyler, as well as the distant long-take style of Theo Angelopoulos and Hou Hsiao-hsien. Studying film history is often our best way to understand the cinema of our moment, and perhaps of our future. At a more primal level, a week of prime examples of the tableau tradition gave me a fine dose of Danish happiness.

For background on the Society for Cognitive Studies of the Moving Image conference this year, try here and here. Earlier blog entries on this site have dealt with other aspects of 1910s cinema: director Yevgenii Bauer, tight staging in De Mille’s Kindling (1915), the emergence of classical film style around 1917, editing in William S. Hart movies, the years 1913 and 1918, and the triumph of Doug Fairbanks. I’ve proposed more complete accounts of 1910s staging strategies, and their impact on film history, in On the History of Film Style and Figures Traced in Light: On Cinematic Staging.

An excellent introduction to Danish cinema of this period is Ron Mottram’s 1988 Danish Cinema before Dreyer, a book which deserves to be reissued or put online. You can sample Danish 1910s films at the DFI archive database, where several clips are posted. Try these fragments: København ved nat (1910), Den frelsende Film (1916), and Kaerlighedsvalsen (1920). DVD versions of some 1910s classics, including The Ballet Dancer, can be ordered from the DFI Cinemateket shop; in the US, the titles are available for institutional purchase from Gartenberg Media. Everyone interested in silent cinema should own the Dreyer, Christensen, Psilander, and Asta Nielsen discs.