The ROW strikes again

Wednesday | October 7, 2009 open printable version

open printable version

The Time that Remains.

Kristin here:

Last year I remarked on how festivals like Vancouver are increasingly showing films from countries that have barely contributed to world cinema until recently. Not surprisingly, the trend continues. Yesterday I saw The Search (dir. Pema Tseden), the second feature to by made in Tibet by a team of Tibetans. (The first was also by Tseden.) It’s strongly reminiscent of Kiarostami’s best-known films, with a small film team traveling through the countryside trying to cast a movie based on a classic indigenous opera.

So far, however, most of the films I’ve seen have been from more established filmmaking regions.

Latin America

Latin American cinema continues to grow beyond Mexico, Brazil, and Peru, largely thanks to European co-productions and occasionally co-productions between countries within the region. For me, the first day of the festival concentrated on Latin America.

The first stop was Peru, with the surprise winner of this year’s Golden Bear at Berlin, Claudia Llosa’s The Milk of Sorrow. The plot concerns Fausta, a young woman whose mother, pregnant with her, was raped and tortured during era of the government’s war against the Shining Path insurgents (1980s-1990s).

Haunted by a fear of being raped herself, Fausta imitates a trick that a woman supposedly employed to fend off attackers. She places a potato in her vagina, hoping that the protruding shoots will repel a would-be rapist. Her terror of leaving home alone limits her freedom, though she manages to take a job as a maid to an eccentric female pianist. Her plight is ironically emphasized by the fact that her uncle is a wedding coordinator, and there are several scenes involving outgoing young women who are attuned to modern life and eager to marry.

The Milk of Sorrow is beautifully shot, with a minimal plot that proceeds at a languorous pace. It fits very much into the art cinema destined primarily for festival and big-city screenings.

Two other two films of the day were distinctly more reminiscent of Hollywood in their pacing and strong plots. Sebastián Silva’s The Maid has a familiar plot, the repressed character who needs to learn to enjoy life and other people. Raquel has served the same family for decades and become obsessed about her own little domain of power, pampering one child she adores, annoying another, and running the household to suit herself. Eventually, when an outgoing second maid is hired, Raquel is surprised to find herself with a friend and begins to come out of her shell.

Two other two films of the day were distinctly more reminiscent of Hollywood in their pacing and strong plots. Sebastián Silva’s The Maid has a familiar plot, the repressed character who needs to learn to enjoy life and other people. Raquel has served the same family for decades and become obsessed about her own little domain of power, pampering one child she adores, annoying another, and running the household to suit herself. Eventually, when an outgoing second maid is hired, Raquel is surprised to find herself with a friend and begins to come out of her shell.

Stylistically there’s nothing of great interest. As with so many films these days, it was shot in real locales, mostly the interior of one large house, and so consists mostly of medium shots and lots of panning. It’s essentially an actor’s film, though, and I could easily imagine it being remade in English as a vehicle for someone like Meryl Streep. It effortlessly balances drama and humor and is continually entertaining. It also features the only unequivocally upbeat ending among the films I’m discussing here, which no doubt says something either about the state of the world or about what filmmakers assume festival programmers look for.

Equally skillful but miles away in tone is the Mexican feature Backyard, by Carlos Carrera. Focusing on the astonishingly frequent rape, torture, and murder of women in Juàrez, the film follows a lone female detective in a police force which refuses to arrest or prosecute any of the perpetrators. (Above, she is confronted with hundreds of photos of the dead and missing.) The reasons behind both the numerous murders and official indifference turns out to be a combination of circumstances: at least one serial killer with the means to pay off the police, the executive of a Japanese factory that doesn’t want bad publicity, and random abusive husbands and young punks who take advantage of the situation to dump their victims in the desert with impunity.

The story is handled in taut classical fashion, intercutting between the detective’s investigations and the story of one young factory girl factory who eventually becomes a victim. This is the stuff of CSI and other crime shows, but all based on a horrific real-life situation that goes beyond what any mainstream drama would dare to show and that continues to this day right, as the title emphasizes, in America’s backyard.

One of the best films we’ve seen so far is Lucrecia Martel’s third feature, The Headless Woman. Although I had admired her visually gorgeous La ciénaga (2001), I found it a bit obvious in its use of the central swamp metaphor to characterize the upper-middle class. The Headless Woman, though, is the epitome of subtlety, with the plot being a puzzle with easily missed clues doled out sparingly. (The Variety review considerably mis-describes what happens, and I suspect others do as well.)

The opening is simple enough, with some boys playing in a dry concrete canal. Nearby, Veró, the woman of the title, helps her sister Josefina shoo a group of noisy kids into one car, while Veró takes off alone in the other. In a remarkable long take, she drives until the car lurches, causing her to bump her head on the windshield. Rather than cutting to what Veró hit, the camera stays with her as she sits, dazed. After a long pause she drives on, and a new framing allows us to briefly glimpse a large dead dog on the road in the distance. Soon the heroine stops and gets out of the car, walking out of focus as we stay in the car and the first heavy drops of a storm strike the windshield (below). One hint: even the exact moment when the rain starts becomes a clue to unraveling the action to come.

The rest of the film stays with Veró, who is present onscreen or off in every scene. We watch her uncertainty, caused by a concussion, but those around her barely notice, attributing her memory loss to tiredness or illness. Eventually Veró tells her husband that she thinks she has killed someone on the road. It would be unfair to reveal more, since experiencing the twists and implications of the plot should be up to the viewer.

Stylistically the film develops on Martel’s characteristic technique of shooting largely in tight shots filmed with highly selective focus. Often one must search for the one significant character. At other times, the camera lingers on Veró’s face, glancing vaguely around with a slight, defensive smile, pretending that nothing is wrong, as more significant actions by the other characters occur out of focus in the background. Often children swarm around, placing the thin thread of the central drama in the context of insignificant gestures of everyday life but making the clues all the harder to notice.

So well hidden is the plot that many viewers will mistakenly decide that it’s a film where nothing much happens. Those who engage with it will discover quite the opposite. But be warned, only a very alert viewer could figure out the plot correctly on a single viewing. I’ll admit I missed a crucial remark on the first pass.

(See also Jim Emerson’s take on The Headless Woman.)

The Middle East

Ahmad Abdalla behind the camera shooting Heliopolis.

David and I both saw Heliopolis, he because it’s a network narrative and I because it’s an interesting district of Cairo that I know only slightly. Egypt may in the past have been the main supplier of mainstream entertainment movies for the Middle East, but Heliopolis is very much an indie, made by first-time director Ahmad Abdalla with a tiny crew shooting on location for a mere two weeks.

In a rare move for this kind of narrative, the characters from the various plotlines barely intersect. Instead, Heliopolis itself is the focus. It’s a suburb near the airport that tourists drive through on their way to the central city but seldom visit. Once an enclave of foreigners, it is now is one of the main districts for middle- and upper-middle-class Egyptians. The beauty of the old buildings, some now shells and threatened with demolition, contrasts with an increasingly westernized youth culture on the streets. Similarly the characters, all with their own aspirations, suffer disappointments in the end, creating a bittersweet tone that becomes generalized to the district.

Lebanon, the Israeli film that won the top prize at the Venice Film Festival, tells a compressed story set during the first day of the Israeli-Lebanon war. It centers on a four-man team in a tank, all going into real combat for the first time. Director Samuel Maoz confines his camera to the interior of the tank for nearly all of the action, limiting our knowledge to the characters’ viewpoints (above). What we see of the war appears through the crosshairs of the mens’ scopes, though the director does not cue us to identify consistently with any of the individual team members.

The increasingly fetid interior of the tank becomes tangibly apparent as the men’s stubbly faces gleam with sweat and grime. At intervals Maoz cuts to grotesquely lyrical details of the tank’s surfaces, with oil oozing into dials or down the walls and filthy liquid on the floor rippling with the machine’s vibrations.

Many of the conventions of the men-at-war film are present, including the young man being killed just as his message assuring his parents of his safety is delivered and the novice gunner who fails to fire when he should but then kills an innocent passerby. But such conventions are renewed through the claustrophobia of the setting and the refusal to hold back in showing the confusion, terror, and savagery of war. Only the opening and closing shots, whether consciously or not an echo of Dovzhenko, offer a hint of peace.

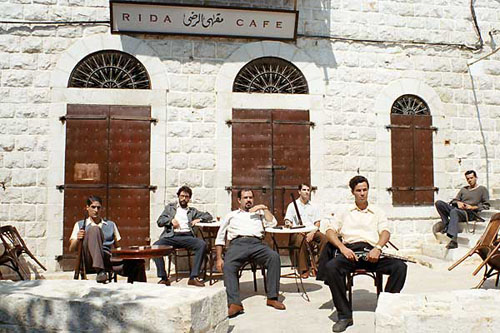

As an admirer of Elia Suleiman’s Divine Intervention, I anticipated most seeing his new film, The Time that Remains: Chronicle of a Present Absentee. It did not disappoint, though it is less ingratiating than the earlier film. Where Divine Intervention is largely based on subtle, ironic comedy played out primarily in Tati-esque long shots, The Time that Remains mixes long stretches of pure drama with the irony. I’ve read tepid reviews that reflect a lack of patience in figuring out what Suleiman was up to this time.

There are no Arrafat-face balloons flying over Jerusalem or fantasy ninja-revenge scenes here. Instead, apparently working with a larger budget, Suleiman ambitiously sets parts of his film in 1948 and other key years of the struggle between Palestinians and Israelis. His father appears as a constant participant in that struggle (seen in dark trousers in the frame at the top). The child Elia shows up partway through and becomes a silent witness to much of this. (As in Divine Intervention, the director plays himself but never speaks.) He acts more as a sympathizer than as an active participant in the conflict, going into exile as a young man and, as we know returning at intervals to make films that comment on the political situation. Hence the “present absentee” of the title.

The older scenes include staged skirmishes and chases, with genuine suspense, before the film settles into the modern era and the humorous, sometimes blackly humorous, life of Suleiman’s aging family and neighbors. As the earlier film dealt with his father’s final illness, the new one lingers over his mother’s.

Despite the drama, there are some characteristically hilarious moments. An unarmed Palestinian man takes out his garbage and paces during a cellphone conversation, ignoring all the while an enormous tank whose gun-turret swivels to cover his every move from a few feet away. Young Palestinians dance to loud music, seen through the glass walls of a discotheque. An Israeli jeep stops outside, vainly trying to make a curfew warning heard over the din, and the soldiers inside unwittingly start bobbing their heads slightly in time to the music.

We’re off to another day of film-viewing and will post again soon.

The Headless Woman.