Archive for December 2009

The ten-plus best films of … 1919

KT here, with some help from DB:

Two entries are enough to create a tradition. Once again, at a time of year when critics are picking their 10-best lists for 2009, we jump back ninety years and give our choices for 1919.

(For our 1917 list, see here, and here for 1918.)

I remarked in last year’s post that it was a bit difficult to come up with ten films, a result perhaps of accidents of preservation or slackening of activity by certain major filmmakers. There was no such problem for 1919, and films had to be bumped off the initial list to keep it to ten. (In fact, you’ll notice we didn’t quite manage to keep it to ten.) Since some people may take these lists as a guide to exploring the cinema of the teens, we’re adding some also-rans at the end, all very much worth watching.

With 1919, we’re approaching the decade when many of the most widely known silent classics were made. Some titles on this year’s list will be very familiar. Erich von Stroheim’s first film came out in 1919, as did Carl Dreyer’s. Ernst Lubitsch, always a prolific director, was particularly busy that year. Other titles are less well-known, still being largely the province of silent-film festivals and archival research.

Three, sadly, are not available on DVD, and some others have to be ordered from sources in their countries of origin. In this day of internet sales around the world, such orders are not difficult. You need, however, a multi-region DVD player.

Charles Chaplin had long since left his knockabout comedy behind and was making more controlled, poetic films by  this point. The Little Tramp was beloved around the world, and numerous impersonators were turning out films to cash in on his popularity. Sunnyside is his most highly regarded film of 1919, in large part because of a dream sequence in which the Tramp wakes up by a little bridge to find himself welcomed by a bevy of wispily dressed young ladies. The subsequent open-air dance displays Chaplin’s extraordinary ability to inject humor into such a scene without marring its lyricism. (The only DVD version currently available in the U.S. is a fuzzy copy.)

this point. The Little Tramp was beloved around the world, and numerous impersonators were turning out films to cash in on his popularity. Sunnyside is his most highly regarded film of 1919, in large part because of a dream sequence in which the Tramp wakes up by a little bridge to find himself welcomed by a bevy of wispily dressed young ladies. The subsequent open-air dance displays Chaplin’s extraordinary ability to inject humor into such a scene without marring its lyricism. (The only DVD version currently available in the U.S. is a fuzzy copy.)

Cecil B. De Mille had begun his series of high-society battle-of-the-sexes films by this point. Male and Female differs from the others in that it is based on a prominent literary source, The Admirable Crichton, J. M. Barrie’s successful 1902 play. The plot involved the butler of a wealthy British family. He becomes their leader when the pampered group is cast away on an unpopulated island. A romance develops between the spoiled daughter, Lady Mary (Gloria Swanson), and Crichton (Thomas Meighan).

De Mille spiced up the story with a fantasy scene based on William Ernest Henley’s popular poem of 1888, “I was a King in Babylon.” It dealt with reincarnation, one of several spiritualist fads of the period, which also included psychic contact with the dead and the fairy photographs that deluded Sir Arthur Conan Doyle. Crichton refers to the poem, leading into a scene of him as king in a Babylon. When a Christian slave girl rejects his advances, he orders her thrown to the lions. The scene providesa glimpse of the costume-epic style that De Mille would increasingly turn to as his career advanced.

Henley, by the way, is largely forgotten today, but another of his poems, “Invictus,” inspired Nelson Mandela and lends its name to the latest Clint Eastwood film.

D. W. Griffith released an impressive lineup of features in 1919, despite the fact that he was also acting as the producer for other directors. His output includes a charming set of pastoral stories A Romance of Happy Valley, True Heart Susie, and The Greatest Question; a belated war film, The Girl Who Stayed at Home; a Western, Scarlet Days; and a melodrama that ranks among his most admired films, Broken Blossoms. Griffith’s status within the industry was  reflected by the fact that this same year same the formation of United Artists as a company to distribute films by him and the other founders, Chaplin, Mary Pickford, and Douglas Fairbanks.

reflected by the fact that this same year same the formation of United Artists as a company to distribute films by him and the other founders, Chaplin, Mary Pickford, and Douglas Fairbanks.

Broken Blossoms owes its simplicity to the fact that Griffith was then making a series of films based on short stories. The title of Thomas Burke’s “The Chink and the Child” sounds offensive today, but it was an ironic reference to the epithet forced upon an idealistic young Chinese man who comes to London’s grim Limehouse district and becomes disillusioned. He falls in love with the delicate Lucy, abused by her violent, drunken father. These three form the main characters. Another Chinese man lusts after Lucy, but for once in Griffith’s work, the sexual threat to the innocent heroine takes second place to her abuse by her father. Lillian Gish and Richard Barthelmess convey the quiet resignation that at intervals gives way to Donald Crisp’s vicious outbursts.

Apart from the strong performances from the three leads, the film was perhaps the first to consistently use the “soft style” of cinematography, an approach that borrowed from a recently established trend in still photography. The hazy views of the Chinese setting in the opening and of the Limehouse docks later on would be enormously influential on films of the 1920s.

Raymond Longford is far and away the least known of the directors in this list. Films were increasingly being made in countries outside the U.S. and Europe, but few have survived. Longford’s The Sentimental Bloke is widely held to be the first major Australian film and perhaps the best of the silent era. Based on a verse poem using vernacular language and serialized from 1909 to 1915, it was set among working-class characters and filmed on location in an inner-city district of Sydney. It follows the reformation of the Bloke, a drinking, gambling man reformed by his love for Doreen. The film’s original intertitles, based on the poem and told in first person by the hero, were too colloquial for Americans to comprehend, and the film failed there, even after a new set of intertitles were substituted.

Raymond Longford is far and away the least known of the directors in this list. Films were increasingly being made in countries outside the U.S. and Europe, but few have survived. Longford’s The Sentimental Bloke is widely held to be the first major Australian film and perhaps the best of the silent era. Based on a verse poem using vernacular language and serialized from 1909 to 1915, it was set among working-class characters and filmed on location in an inner-city district of Sydney. It follows the reformation of the Bloke, a drinking, gambling man reformed by his love for Doreen. The film’s original intertitles, based on the poem and told in first person by the hero, were too colloquial for Americans to comprehend, and the film failed there, even after a new set of intertitles were substituted.

The Sentimental Bloke was restored in 2004 and this past April appeared in a DVD set prepared by the Australian National Film & Sound Archive. A supplementary disc includes historical material, information on the new musical accompaniment, and an interview with Longford. A book of historical essays is also included in the box, which is available directly from the DVD company Madman. (Note that although there is no region coding, it is in the PAL format.)

When I was studying film in graduate school, Ernst Lubitsch’s German period was known mainly for the 1919 historical epic Madame Dubarry. There was little known about the two comedies that came out that year, perhaps the most amusing and delightful of all his German films in this genre: Die Austernprinzessin (“The Oyster Princess,” though seldom called by that title) and Die Puppe (“The Doll,” also a little-used name).

It’s hard to choose which of these three is Lubitsch’s best for the year. Ironically Madame Dubarry isn’t watched much any more, and it’s not on the recent DVD set “Lubitsch in Berlin,” though the two comedies are. Complete prints are rare, due in part to censorship. (If the print you see ends with a close-up of the heroine’s head held up after she is executed, you’ve probably been watching a reasonably complete version.) It may seem a bit stodgy upon first viewing, but I warmed up to it during repeated screenings while researching my book on Lubitsch’s silent films. There are many excellent moments: the extended series of eyeline matches when Louis XV first sees Jeanne, the masterfully timed and staged long take when Choiseul refuses to let Jeanne accompany Louis’s coffin, and a meeting among the revolutionaries that ends as Jeanne reacts in horror to their bloodthirsty plans, backing dramatically into shadow in the background (below).

Given how different these films are, I’m going to declare a tie between Madame Dubarry and one of the comedies. Wonderful though The Oyster Princess is, I’m opting for Die Puppe (above). Its story-book opening and stylization are charming. The hilarious scenes in the doll workshop and the monastery full of greedy monks fill out the plot, making it considerably denser than that of Die Austernprinzessin.

As with Lubitsch, when I was first studying film and for many years thereafter, Swedish director Mauritz Stiller was known mainly for one film, Sir Arne’s Treasure (Herr Arnes Pengar), though an abridged version of The Saga of Gösta Berling also circulated. Sir Arne’s Treasure was assumed to be his masterpiece. The gradual rediscovery and restoration of other Stiller films from the 1910s has considerably broadened our view of him. Perhaps Sir Arne’s Treasure is not the solitary, towering masterpiece it was long thought to be. Still, it holds up well upon revisiting.

It is a period piece set in a small seaside community. A group of foreign men massacre most of a family, in search of their mythical riches. They are forced to remain in the village when the ship in which they are to sail becomes  icebound. The surviving daughter of the family unwittingly falls in love with one of the killers.

icebound. The surviving daughter of the family unwittingly falls in love with one of the killers.

Sir Arne’s Treasure was one of the films which gained the Swedish cinema of the 1910s the reputation for brilliantly exploiting natural landscapes. Few silent films have exploited actual winter settings so well. The actors are clearly working in genuine snow; one can sometimes see their breath fog as they speak. Atmospheric shots show the wind sweeping snow across the ice. Stiller uses the blank backgrounds created by the snow to create stark, simple compositions of dark figures and objects.

Kino’s DVD release uses a print from Svensk Filmindustri’s own archives. To my eye, the tinting used is too dark, especially since much of the action naturally takes place in the dark of the northern winter days. Deep blues somewhat obscure parts of the action. Still, the darkness adds to the brooding tone that pervades the story.

Erich von Stroheim’s first film, Blind Husbands, is the only one he completed that has come down to us in more or less its original version. As the director’s artistic ambitions expanded, his studios’ willingness to accommodate the growing  length and scope of his films diminished. His features of the 1920s were re-edited without his consent, most notoriously when the eight-hour naturalistic film Greed (1924) was released in a version that ran little more than two hours. For many the original remains at the top of the wish list for lost films to be recovered someday. (Number one on my list is Lubitsch’s Kiss Me Again, released in 1925 just before his masterpiece, Lady Windermere’s Fan.)

length and scope of his films diminished. His features of the 1920s were re-edited without his consent, most notoriously when the eight-hour naturalistic film Greed (1924) was released in a version that ran little more than two hours. For many the original remains at the top of the wish list for lost films to be recovered someday. (Number one on my list is Lubitsch’s Kiss Me Again, released in 1925 just before his masterpiece, Lady Windermere’s Fan.)

Blind Husbands is my favorite among von Stroheim’s films. It tells its story of sin and punishment with a lighter touch than his later films would. The director plays a would-be seducer of a neglected wife when the group converges in a village for a mountain-climbing vacation. Von Stroheim’s eye for striking compositions against the snow-clad landscapes and his skillful use of the inn’s hallways and doors to convey the characters’ shifting relationships show an already mature grasp of the art form. (See right, where the villain eyes the heroine in her room but is himself watched by the protective guide in the hallway between the rooms.)

Maurice Tourneur’s Victory runs a mere 63 minutes in its current version, but the original footage count suggests that what we have is substantially complete. That’s somewhat short for a feature by a major director at this point in history, but the simple, intense plot, based on a Joseph Conrad short story, benefits from the compression. The protagonist is a man who has escaped his past and lives as a virtual hermit on a South Seas island. Attracted despite himself, he befriends a young woman playing in a visiting orchestra and rescues her from the abuse of the orchestra’s owner and the lustful advances of the local hotel owner. Returning with the woman to his lonely island, he faces the intrusion of three thugs deceived by the vengeful hotel owner into thinking that the hero has riches hidden on his island.

By this point Tourneur has fully mastered the “rules” of classical continuity style and of three-point lighting. Many of the compositions in Victory look like they could have been made in the 1930s. When I first saw the film about thirty years ago, I found the earliest case of true over-the-shoulder shot/reverse shot that I had ever seen:

Since then, David has found an earlier one that sort of qualifies (maybe more on this in an upcoming entry), but this is a purer case.

Tourneur had also developed a distinctive approach to filming settings in long shot with framing elements within the mise-en-scene and figures silhouetted in the foreground (see top). In general the lighting is superb. Few Hollywood directors had reached this level of sophistication by 1919.

Victory has been released on DVD largely because it features Lon Chaney as one of the thugs. Image offers it paired it with another Chaney film. For some reason the titles are out of focus, but the rest of the film fortunately is in good condition and presents Tourneur’s visual style well.

DB’s picks:

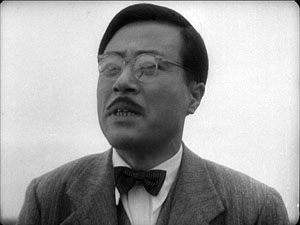

Carl Theodor Dreyer began his film career writing scripts at the powerful Danish studio Nordisk. When he started directing, however, World War I had destroyed Nordisk’s markets, and the American cinema was on the rise. Dreyer’s generation was the first to register the impact of the emerging Hollywood cinema, and he displayed his understanding of Griffithian technique in The President (Praesidenten).

The English title should probably be something like “The Head Magistrate” or “The Presiding Judge,” and the plot appropriately sets up a tension between justice and personal obligation. One of Nordisk’s favored genres was the “nobility film,” in which illicit passion plunges a wealthy man or woman into the lower depths of society. Dreyer gave the studio a nobility film squared, using flashbacks to show how two generations of men in a family have seduced working-class women. The present-day drama displays the crisis that ensues when a respected judge realizes that the woman to be tried for infanticide is his illegitimate daughter. Dreyer’s abiding concern for the exploitation of women under patriarchy begins in his very first film.

From the early 1910s, Danish films displayed a mastery of tableau staging and careful pacing. But The President bears the mark of American technique in its bold close-ups and reliance on editing to build up its scenes. (There are nearly 600 shots in the film, yielding a rate of about 8.8 seconds per shot—quite swift for a European film of the era.) Perhaps more important are Dreyer’s efforts to shove aside the heavy furnishings of bourgeois melodrama. Compare the overstuffed set of Hard-Bought Glitter (Dyrekobt Glimmer, 1911) to this daringly bare one, with its sweep of cameos.

In the late teens, other Danish directors were moving toward simpler settings, but The President carries this tendency to geometrical extremes. Dreyer’s walls, bare or starkly patterned, isolate the players’ gestures and heighten moments of stasis. The result is one of the most adventurously designed film of its time, and if some of its experiments do not quite come off, already we can see that impulse toward abstraction that would be given full rein ten years later in La Passion de Jeanne d’Arc. The all-region DVD from the Danish Film Institute provides a somewhat dark tinted copy with original intertitles and English translations.

Dreyer deeply admired Victor Sjöström, who had already given Swedish cinema some of its enduring masterpieces: Ingeborg Holm (1913), Terje Vigen (1917), The Girl from Stormycroft (1917), and The Outlaw and His Wife (1918). Sjöström would go on to make The Phantom Carriage (1921), The Scarlet Letter (1926), and The Wind (1928). Several other outstanding movies he signed remain little known; worth watching for are The Girl from Stormycroft (1917), Karin Ingmarsdotter (1920), and the deeply moving Mästerman (1920; look for this on our list next year). Among these unofficial classics Sons of Ingmar (Ingmarssönerna, 1919) stands out especially.

Dreyer deeply admired Victor Sjöström, who had already given Swedish cinema some of its enduring masterpieces: Ingeborg Holm (1913), Terje Vigen (1917), The Girl from Stormycroft (1917), and The Outlaw and His Wife (1918). Sjöström would go on to make The Phantom Carriage (1921), The Scarlet Letter (1926), and The Wind (1928). Several other outstanding movies he signed remain little known; worth watching for are The Girl from Stormycroft (1917), Karin Ingmarsdotter (1920), and the deeply moving Mästerman (1920; look for this on our list next year). Among these unofficial classics Sons of Ingmar (Ingmarssönerna, 1919) stands out especially.

A prologue shows lumbering, somewhat thick-headed Ingmar climbing a ladder to heaven, where generations of Ingmars sit in dignity around a massive meeting-room (see below). There his father tells him that he must find a wife. But Ingmar then explains that he once took a wife, with unhappy results. Some long flashbacks ensue, showing Ingmar forcing a young woman to marry him. The plot takes some doleful turns, with the result that the woman is sent to prison.

Running over two hours (and initially released in two parts), Sons of Ingmar has a fittingly lengthy climax that portrays the pains of reconciliation between a sensitive woman and an inarticulate man. In the film’s final scenes, Sjöström risks a delicate emotional modulation that would daunt a director today. Using Hollywood continuity cutting with a casual assurance, he relies on subtly timed cuts and changes of shot scale to trace the couple’s wavering guilts and hopes. These last scenes have a human-scale gravity that balances the weighty paternal authority of the heavenly sequences. In Theatre to Cinema our colleagues Lea Jacobs and Ben Brewster have written a penetrating analysis of the performances of Sjöström as Ingmar and Harriet Bossa as Brita.

Unhappily, we know of no video version of this wonderful film. It should be a top priority for DVD companies specializing in silent cinema.

Another 1919 candidate for ambitious DVD purveyors is Louis Feuillade’s great serial Tih Minh. It has been overshadowed by Fantômas (1913-1914), Les Vampires (1915-1916), and Judex (1917), but it has a playful charm of its own. It is, in a way, the anti-Vampires. Instead of chronicling the triumphs of an all-powerful secret society, this six-hour saga gives us a few ill-assorted conspirators who inevitably fail at every scheme they try. The plot is no less far-fetched than that of the earlier serial, but the twists are more comic than thrilling. (Which is not to say that we’re denied some astonishing real-time stunt work performed by the actors, as above.) The film’s genial tone assures us that nothing bad will happen to the poor girl Tih Minh, but the villains will get enjoyably harsh punishment. In the course of the adventure three couples are formed, the routines of provincial life are filled in with leisurely detail, and the whole thing ends with a big wedding.

Unlike the Paris-bound serials, Tih Minh allowed Feuillade to apply his elegant staging skills to natural landscapes. By now he was filming in Nice, and the chases and fistfights are enhanced by gorgeous mountains, vistas of water, and hairpin roads. More than one connoisseur has confessed to me that this is their favorite Feuillade serial, and it’s hard to disagree. I always find that viewers are carried away by its zestful tale of good people who come to a good end.

DB’s runner-ups: Perhaps not as fine as the above, but definitely of bizarre interest, are two Robert Reinert films from 1919. The title of Opium pretty much sums up this fevered movie. It includes sinister Asians, drug-addled doctors, a lions’ den, and Conrad Veidt in a suicide-haunted performance that makes his Cesare role in Caligari look underplayed (see right). Later in the same year Reinert gave us an even more overwrought tale, Nerven. This is a movie about collapse–the collapse of a community, of a business, and of the tormented minds of buttoned-up citizens. Reinert renders melodrama in images of controlled frenzy unlike any others I know from the period. Had his films been as widely seen as the official Expressionist classics, I think he would be much admired today. I analyze these two movies in Poetics of Cinema, and say a bit about them in this entry. A DVD of Nerven is available from the Munich Film Archive.

DB’s runner-ups: Perhaps not as fine as the above, but definitely of bizarre interest, are two Robert Reinert films from 1919. The title of Opium pretty much sums up this fevered movie. It includes sinister Asians, drug-addled doctors, a lions’ den, and Conrad Veidt in a suicide-haunted performance that makes his Cesare role in Caligari look underplayed (see right). Later in the same year Reinert gave us an even more overwrought tale, Nerven. This is a movie about collapse–the collapse of a community, of a business, and of the tormented minds of buttoned-up citizens. Reinert renders melodrama in images of controlled frenzy unlike any others I know from the period. Had his films been as widely seen as the official Expressionist classics, I think he would be much admired today. I analyze these two movies in Poetics of Cinema, and say a bit about them in this entry. A DVD of Nerven is available from the Munich Film Archive.

KT’s runners-up: I suppose that there will be some tongue-clicking over the fact that Abel Gance’s J’accuse! is not present in our list. There’s no doubt it’s historically important and influential, but it’s also heavy-handed and doesn’t add the leavening of humor to its melodrama, as some of the above films do. But it does deserve a mention in an overview of 1919. (I’ve posted about what I see as Gance’s limitations here.)

Last year I put Marshall Neilan’s Mary Pickford vehicle, Stella Maris, in the top ten. I’d be tempted to do the same with his (and her) Daddy-Long-Legs, but this year there’s a lot more competition. But it’s a charming film, and the great cinematographer Charles Rosher provides another series of beautiful images using the new three-point lighting system. It was the first Pickford film into Germany after the war and considerably influenced Lubitsch and other German directors.

Similarly, in a year with fewer major films, Victor Fleming’s When the Clouds Roll By, a wacky, inventive tale of superstition and psychological manipulation starring Douglas Fairbanks, would make the main list. David illustrated some of that inventiveness in his epic entry on Fairbanks.

Within a few years, compiling our 90-year picks will become increasingly difficult. Experimental cinema will blossom, as will animation. The Soviet Montage and German Expressionist movements will get started, and French Impressionism, still a minor trend in the late teens, will expand. Filmmakers like Murnau, Lang, Vidor, and Borzage will gain a higher profile, and more films by veteran directors like Ford will survive. Maybe we’ll have to expand the annual list even further. . . .

A very happy New Year to all our readers! Assuming we make it through the security lines, we shall be celebrating New Year’s Eve on a plane bound for Paris, where David will be doing a lecture series over the first few weeks of January. Paris is the world capital of cinema, at least as far as the diversity of films on offer goes, so we shall no doubt find occasion to blog while there.

Sons of Ingmar.

Projections on glass

Christa Bothwell, While You Are Sleeping (2007).

Db here:

I must be obsessive. Whenever I get into a museum, I see movies hovering over the exhibits. You want proof? Go here or here or here. Kristin has dabbled in such speculation too, here.

The most recent example came last week. My sister Darlene is recovering from surgery, and as an excursion she, Kristin, and I visited the magnificent Corning Glass Museum in the southeastern tier of New York state. I hadn’t been there since the 1950s, when I was a kid. The museum was flooded in 1972, but after successive, ever more ambitious restorations, it is now a landmark. Its dignified modernist façade houses a sensory extravaganza.

Glass as an artistic medium is usually associated with either well-designed practical objects, like bottles and glassware, or sculpture, as in the Studio Glass movement founded by Harvey Littleton, who worked right here at the University of Wisconsin—Madison. Beyond that, what I know about glass you can put in—well, a shot glass. So I was pleased to learn how glass art connects to some issues that interest me about the visual arts generally and film in particular.

Take illusionism. We’re familiar with the ways that the paintings of Dalí and Magritte use the rules of perspective to create hallucinatory landscapes. And we know about classic trompe l’oeil pictures like this seventeenth-century painted letterboard by Cornelis Gijbrechts.

But I didn’t expect to find trompe l’oeil in glass.

This is Cup in Cup (1986) by Ann (Wärff) Wolff . The spectral little cup is inscribed in the surface. Like all good trompe l’oeil, this is best seen from a single standpoint.

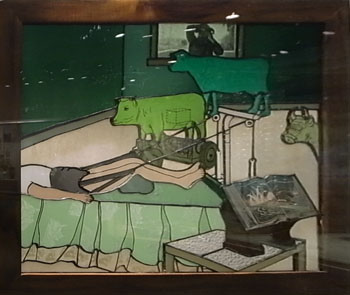

Glass is literally all around us, as the stuff of our windows. In a 1976 image, Richard Posner (no, not the judge) creates a film-like scene by leaving crucial information out of frame. Another Look at My Beef with the Government, from the “Picture Window” series, shows him in traction while cattle, and the artist himself outside the window, look on.

This is part of a series called “Picture Window.” The image pictures a window, and it gives us a window onto the scene, but the phrase also suggests that a window can itself be a picture. In this case, it’s Posner’s comment on serving as a conscientious objector during the Vietnam War.

There’s an ongoing debate about whether to consider glass a solid or a very viscous liquid, sort of the ultimate maple syrup. Its fluid qualities make it ideal for evoking movement. Swirls, waves, bursts, and sprouting capillaries are everywhere in the Corning collections. One of the best examples is Littleton’s now-classic Red/Amber Sliced Descending Form (1984).

The slickness of the surfaces lends a palpable wriggling to the snakelike forms of Dale Chihuly’s Cadmium Yellow-Orange Venetian #398 (1990).

Glass makes these coils glisten.

Chihuly was another Madisonian; a more cheerful twisty work graces our campus’s Kohl Center.

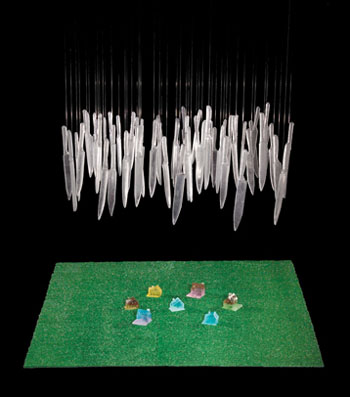

Another sort of movement: Silvia Levinson’s It’s Raining Knives (1996-2004) shows stalactite-like daggers bearing down on a suburban landscape. The slender wires suggest danger hanging by a thread, but they also evoke speed lines, as if the knives are caught in mid-flight.

Levinson is Argentine, and the piece responds to the dictatorship that displaced Juan Perón—during which many of her family vanished or were imprisoned. You can read more about the background to the piece here.

Finally, probably the most filmlike thing I saw: An impression of interrupted movement is combined with an old-fashioned superimposition in Christina Bothwell’s While You Are Sleeping, which surmounts this entry.

After four hours of dazzlement, I was re-persuaded that Eisenstein was right: All the arts are connected, in devious ways, to film.

The Museum has listed many of the items on exhibit, including illustrations, in various pages and pdf files here. Most of the shots here were taken by me, but the Littleton and the Levinson images come from the Museum website.

Coming soon: Our list of the best films of 1919.

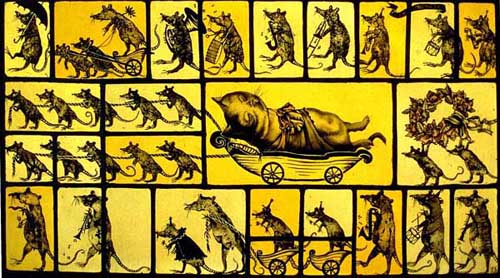

Judith Schaechter, Jazz Funeral for Didi (1994). Not in the Corning collection, but proto-cinematic in a Marey-and-Muybridge way. (And, I admit, reminiscent of Chris Ware.) See other lively Schaechter stained-glass work here and in her book Extra Virgin.

Robin Wood

DB here:

Robin Wood has just died. Kristin and I knew him a little; we recall a convivial dinner with Robin and Richard Lippe in New York during the 1970s. We knew him chiefly on the page, as a writer whom we valued enormously. I take this moment to acknowledge his death, to suggest his importance, and to praise his memory.

Today it’s hard to imagine the impact that Wood had on film criticism in the late 1960s and early 1970s. I first encountered his writing while I was in high school. I desperately wanted to know more about movies, but the nearest towns had no libraries. So I wrote to every film magazine I had heard of and said I was considering subscribing. Could they please send me a sample copy? The issues that came through included, most memorably, the Sarris “American Directors” issue of Film Culture and the Howard Hawks issue of Movie. Both changed me forever.

The Hawks issue contained Wood’s essay on Rio Bravo, a sort of draft for what would become one of his most important statements.

Hawks, like Shakespeare, is an artist earning his living in a popular, commercialized medium, producing work for the most diverse audiences in a wide variety of genres. Those who complain that he “compromises” by including “comic relief” and songs in Rio Bravo call to mind the eighteenth century critics who saw Shakespeare’s clowns as mere vulgar irrelevancies stuck in to please the “ignorant” masses. Had they been contemporaries of the first Elizabeth, they would doubtless have preferred Sir Philip Sydney (analogous evaluations are made quarterly in Sight and Sound). Hawks, like Shakespeare, uses his clowns and his songs for fundamentally serious purposes, integrating them in the thematic structure. His acceptance of the underlying conventions gives Rio Bravo, like Shakespeare’s plays, the timeless, universal quality of myth or fable.

Nearly every Wood virtue is already here. He takes it for granted that conventions are crucial to understanding and judging cinema. He refuses an evaluative split between high culture and popular culture. He insists that worthy films have serious thematic implications—in Rio Bravo, a link between self-respect and peer respect. He shows the film’s complexity through shrewd comparison (in the book on Hawks, High Noon will provide the telling contrast). And he gives the whole thing a polemical edge with the sideswipe at Sight and Sound, a target for many years to come.

But it was the books, in an apparently unending flow, that established Wood as a leading voice, and not only for me. I can’t convey the excitement that was ignited by Hitchcock’s Films (1965), Howard Hawks (1968), and Ingmar Bergman (1969), quickly followed by the monographs on Penn (1970) and Ray’s Apu Trilogy (1971). Nearly all books of film criticism were then simply collections of reviews. Wood’s stood as through-written, pondered over, carefully carpentered monographs, comparable to the best literary analysis. These studies showed, in incisive detail, what most auteur criticism simply proclaimed: great directors expressed their personal vision of life in and through cinema. Wood showed, scene by scene and sometimes shot by shot, that movies harbored layers of feeling and implication in their finest grain of detail. Without fanfare he introduced “close reading” to film criticism. Although never academic in the narrow sense, he took cinema as seriously as did critics of art or music or literature.

In fact, the word “serious,” a tonal center of the Rio Bravo essay, might be the keyword of his career. Partly that seriousness is intellectual. From the start Wood’s prose had a rectitude that was argumentative in the best sense. The Hitchcock book begins by imagining the best case one can make against the director; he then demolishes it piece by piece. The author does not try to woo us. He respects his reader enough to spell out his claims and to invite a skeptical reply. At last, we thought: An honest man.

The idea of seriousness took on a deeper import, one shaped by the indelible influence of F. R. Leavis. For Wood as for Leavis, great art inevitably grappled with the ultimate demands of living. Close analysis was nothing unless it revealed the author’s felt engagement with human values. This state of affairs imposed equally stringent obligations on the critic. Nothing could be farther from the snappy badinage and instant turnaround of Netwriting than Wood’s obstinate gravity. Flippancy and showing off had no place in serious criticism. Being a critic, analyzing and interpreting and judging, was a heavy responsibility, and every word had to be weighed. The very status of film as art, indeed the status of art itself, was at stake.

In a passage I cannot find on short notice, Wood once observed that a critic could not write “seriously” about Hou Hsiao-hsien’s Flowers of Shanghai after one viewing. Accordingly, not until he could study the film on DVD did he produce a characteristically penetrating essay. It’s a piece that anyone would be proud to sign, but Wood concludes:

I’m afraid the above analysis, in spelling things out, may have suggested that the film is more schematic than it actually is. Its “scheme” is in fact so subtly worked that it has taken me at least six complete viewings (together with more replays of individual scenes and moments than I can count) to disentangle it from all the detail of the realization. The above account is offered humbly, as a beginning.

This passion for nuance did not lead to a sort of scientific objectivity. The responsibility of criticism made writing inescapably personal. The critic responds to the work as a living being, as a “whole man alive”—a Leavis phrase that Wood was wont to quote. Personal Views, the title of Wood’s first collection of essays, signalled both the artistic visions expressed in the films he studied and the sincerity with which he advocated for or inveighed against a film, a trend, or a system of ideas.

I don’t know any critic whose intellectual and political horizons expanded as much as Wood’s did in the 1970s. Since criticism was for him a form of living, he took his readers along as he discovered structuralist theory (which he had once attacked), accepted some tenets of psychoanalytic theory, and launched ferocious attacks on patriarchy and capitalism. The same moral fervor that informed his 1960s writing became focused upon the political oppression of women, gays, the poor, and free thought. Now, he suggested, the apparent stability of “ordinary” life relied upon psychological and social repression. If one theme runs through his work—that of the precariousness of decent human relations in the face of disorder—it finds its late expression in his belief that conservative politics, in the name of maintaining order, is implacably bent upon destroying our kinship with others. In a sense, CineAction, the journal that he co-founded, was his latter-day Movie, a forum for his new commitment to criticism that promoted progressive social change.

The art he cared most about, I believe, laid bare the struggle between order and disorder. In his first book, he argues that Hitchcock shows comfortable “ordinary” people faced with a world coming to pieces. Across his career Wood ceaselessly questioned what exactly this normal order consists of. Coming out as a gay man, he devoted his finely meshed attention to reading films politically. Now those social forces that he once defined simply as threats to stability, such as the war in Bergman’s Shame, revealed themselves as products of warped political systems. The horror film presents disorder as a monstrous threat to bourgeois norms, yet it can become a powerful force in questioning those conceptions. For nearly four decades Wood recorded his efforts to grasp the concrete social implications behind the films he loved and those, increasingly from Hollywood, he found evasive and duplicitous. In all, complacent acceptance of the status quo was the enemy of the seriousness he prized. When he died he was at work on a study of Michael Haneke.

The seriousness of great artists, he came to believe, was inescapably political. Yet while this made him reevaluate Hawks and Hitchcock, it did not lead him to absolute repudiations. Always a believer in the validity of intuitive response, Wood would trust his sensibility more than the dictates of academic “frameworks” and theoretical systems. A 2004 set of notes on Ozu concludes:

These late Ozu films are detailed and highly intelligent critical studies in cultural change which ultimately defy the application of such terms as “progressive,” “regressive,” “conservative,” etc. . . . “Change” is not necessarily for the better (though our current culture is constantly telling us that of course it is) . . .—an obvious ploy of corporate capitalism, which depends upon the mystification for selling its products. If we gain new freedoms, we should also beware of casually casting off the past without asking ourselves what in it—what standards of seriousness, what beliefs, what aspects of our lives—might be worth preserving. I find all these thoughts in Ozu, incomparably expressed.

Through all the constant reappraisals of films, all the unsparing reconsiderations of his own judgments, one hears the same forthright, urgent voice. Leavis suggested that the good critic always asked, in effect, “This is so, isn’t it?” Wood’s writing consists of firm assertions accompanied by challenges to respond as an equal. The invitation is set out in an impassioned conversational cadence, complete with italics and appositional phrases. In search of clarity, Wood is prepared to argue and dissect forever; who else would produce not one but two books rethinking his defense of Hitchcock? Yet this brisk voice can also move us by its simplicity, as in the sentences concluding that little book on the Apu trilogy.

Suddenly the boy relaxes, and rushes forward into his father’s arms. The film ends with him seated on Apu’s shoulders as Apu walks away towards the future. In accepting the child, he has accepted life, has accepted the death of Aparna. Whether or not he is going back to become a great novelist is immaterial: he is going back to live.

Wood’s essay on Rio Bravo is in Movie no. 5 (undated, 1963?), 25-27. His “Flowers of Shanghai” appears in CineAction no. 56 (September 2001), 11-19. “Notes toward a Reading of Tokyo Twilight (Tokyo boshoku)” is in CineAction no. 63 (April 2004), 57-58.

For a wide-ranging and growing set of links to eulogies for Robin Wood, visit David Hudson at The Auteurs Daily and Catherine Grant at Film Studies for Free. A recent interview framed by enlightening commentary is Armen Svadjian’s 2006 tribute, “A Life in Film Criticism: Robin Wood at 75.” Wood’s 2008 list of the films he most valued is on the Criterion site here. D. K. Holm maintains an invaluable, continually updated bibliography of Wood’s writings here.

François Truffaut, Day for Night (1973).

Kurosawa’s early spring

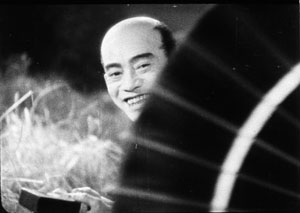

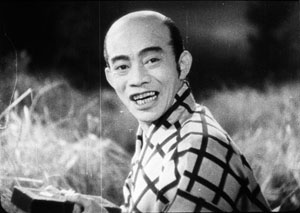

The Most Beautiful (1944).

For Donald Richie

DB here:

Cinephile communities aren’t free of peer pressure. Sometimes you must choose or be thought a waffler. In postwar France, the debate within the Cahiers du cinéma camp often came down to big dualities. Ford or Wyler? German Lang or American Lang? British Hitchcock or American Hitchcock? In the America of the 1960s and 1970s, we had our own forced choices, most notably Chaplin or Keaton?

This maneuver assumed that a simple pair of alternatives could profile your entire range of tastes. If you liked Chaplin, you probably favored sentiment, extroverted performance, and direction that was straightforward (“theatrical,” even crude). If you liked Keaton, you favored athleticism, the subordination of figure to landscape, cool detachment, and geometrically elegant compositions. One director risked bathos, the other coldness. The question wasn’t framed neutrally. My generation prided itself on having “discovered” the enigmatic Keaton, in the process demoting that self-congratulatory Tramp. Keaton never begged for our love.

Of course it was unfair. The forced duality ignored other important figures—Harold Lloyd most notably—and it asked for an unnatural rectitude of taste. Surely, a sensible soul would say, one can admire both, or all. But we weren’t sensible souls. Drawing up lists, defining in-groups and out-groups, expressing disdain for those who could not see: it was all a game cinephiles played, and it put personal taste squarely at the center of film conversation.

In the 1950s another big duality slipped into Paris-influenced film talk. Virtually nobody knew about Ozu, Shimizu, Gosho, Naruse, Shimazu, Yamanaka, et al., so two filmmakers had to stand in for the whole of Japanese cinema. Mizoguchi or Kurosawa?

A problematic auteur

For Cahiers the choice was clear. Mizoguchi was master of subtly shaping drama through the body’s relation to space, thanks to quiet depth compositions and modulations of the long take. In Japan, land of exquisite nuance, the dream of infinitely expressive mise-en-scene seemed to have come true.

There seemed to be nothing nuanced about Kurosawa, whose brash technique, overripe performances, and propulsive stories seemed disconcertingly “Western.” Sold, like Satyajit Ray, as a humanist from an exotic culture, he played into critics’ eternal admiration for significance. This director wanted to make profound statements about the bomb (I Live in Fear), the relativity of truth (Rashomon), the impersonality of modern society (Ikiru), and the complacency of power (High and Low, The Bad Sleep Well). Even his swordplay movies seemed moralizing, with the last line of Seven Samurai (“The victory belongs to these peasants. Not to us.”) summoning up a cheer for the little people. Kurosawa could thus be assigned to Sarris’s category of Strained Seriousness. “He’s the Japanese Huston,” said a friend at the time.

But there was no overlooking his cinematic gusto. He made “movie movies.” He flaunted deep-focus compositions, cunningly choppy editing, sinuous tracking shots (through forests, no less), dappled lighting, and abrupt addresses to the viewer, by a voice-over narrator or even a character in the story. He exploited long lenses and multiple-camera shooting at a period when such techniques were very rare, and he may have been the first director to use slow-motion for action scenes. Bergman, Fellini, and other international festival filmmakers of the 1950s didn’t display such delight in telling a story visually. If you liked this side of his work, you overlooked the weak philosophy. On the other hand, if you found the style too aggressive, it could seem mere calculation on the part of a man with something Important to say.

The case for the defense was made harder by the fact that he was a controversial figure at home as well. Japanese critics I met over the years expressed puzzlement about Western admiration for the director’s style. I was once on a panel in which an esteemed critic blamed Kurosawa for influencing Western directors like Leone and Peckinpah. His violence and showy slow-motion had helped turn modern cinema into a blunt spectacle. No wonder Lucas, Spielberg, Coppola, and Walter Hill have loved this macho filmmaker.

Today passions seem to have cooled, but I should confess that my own tastes remain rooted in my salad days (1960s-1970s). I could live happily on a desert island with only the films of Ozu and Mizoguchi. I’d argue forever that Japanese cinema of the 1920s through the 1960s is rivaled for sheer excellence only by the parallel output of the US and France. (For more on this matter, see my blog entry on Shimizu.) On Kurosawa, however, my feelings are mixed. I still find most of his official classics overbearing, and the last films seem to me flabby exercises. But there are remarkable moments in every movie. Overall, I’ve responded best to his swordplay adventures; Seven Samurai was the first film that showed me the power of the Asian action aesthetic. I think as well that his earliest work up through No Regrets for Our Youth (1946), along with the later High and Low and Red Beard, are extraordinary films. And, like Hitchcock and Welles, he is wonderfully teachable.

We don’t live on desert islands, and gradually we’re gaining easy access to the range of Japanese filmmaking of its great era. We can start to see beyond the fortified battlements set up by generations of critics. With so many points of entry into Japanese cinema, mighty opposites lose their starkness; polarities dissolve into the long tail. Nevertheless, personal tastes take you only so far, and objectively Kurosawa still looms large. Whatever your preferences, it’s important to study his place in film history and film art.

Gauging that place involves thinking outside some traditional conceptions of how films work. Like most ambitious Japanese directors, Kurosawa provides bursts of cinematic swagger. This six-shot passage from Rashomon revels in its own strangeness.

Here traditional over-the-shoulder shots submit to a brazen geometry. Out of an ABC film-school technique Kurosawa creates a cascade of visual rhymes and staccato swiveled glances. Yes, an ingenious critic could thematize this bravura passage. (“The symmetries put the central characters, each of whom asserts a different version of what happened, on the same visual and moral plane.”) Instead I’m inclined to think that the shots constitute a little thrust of “pure cinema,” a brusque cadenza that keeps our eyes, if not our hearts or minds, locked to the screen. From this angle, Kurosawa claims some attention as an inventor of, or at least tinkerer with, the disjunctive possibilities of film form.

His centenary arrives in 2010, and the occasion is celebrated by Criterion with a set of twenty-five DVDs. Most of these titles have already been available singly, and the discs lack all the bonus features we have come to admire from the company. Yet the crimson and jet-black box, the discreet rainbow array of slip cases, and the subtly varied design of the menus add up to a good object, like the latest iPod—something you want even if it means re-buying things you already have. There’s also a handsome picture book with notes by Stephen Prince on each film.

To viewers who need the assurance of cultural importance, this behemoth announces: You must know Kurosawa to be filmically literate. And that’s more or less true. Just as important, the inclusion of four rarities from his early years gives the collection a claim on every film enthusiast’s attention. One hopes that those titles will eventually appear separately, perhaps in an Eclipse edition. [See 15 May 2010 update at the end.] For now these copies of the wartime features are far better than the imports I’ve seen.

The Big Box makes it tempting to mount a career retrospective on this site, but that’s far beyond my capacity. Future blog entries may talk more of this complicated filmmaker, but for now I’ll confine my remarks to these early works. They offer plenty for us to enjoy.

Audacious propaganda

Although Kurosawa was only seven years younger than Ozu, he belongs to a distinctly different generation. Ozu directed his first film in 1927, at the ripe age of twenty-four. He grew up with the silent cinema and made masterful films in the early 1930s, during the long twilight of Japanese silent filmmaking. Kurosawa became an assistant director in the late 1930s. Although he evidently directed large stretches of Yamamoto Kajiro’s Horse (1941), he didn’t sign a feature as director until he was thirty-three. His closest contemporary, and a director whom some Japanese critics consider his superior, is Kinoshita Keisuke. Kinoshita was born in 1912 and his first feature, The Blossoming Port, was released in the same year as Kurosawa’s debut.

Kurosawa and Kinoshita began their careers making wartime propaganda. Their task was to display Japanese self-sacrifice and spiritual purity in stories of both the past and the present. In the Sanshiro Sugata films (1943, 1945), Kurosawa presents judo as an integral part of Japanese tradition and a path to enlightenment. Much of the external conflict is devoted to uniting martial arts (ju-jitsu, karate) under the rubric of the less aggressive but more powerful judo, and to showing how it can defeat American-style boxing. But the internal dimension is also important. Judo is a means of tempering character and accepting one’s proper place. Humble, unflagging devotion to one’s vocation becomes heroic.

The same quality can be found in The Most Beautiful (1944), a story of teenage girls working in a factory manufacturing lenses for binoculars and gunsights. Vignettes from the girls’ lives dramatize the need for cooperation and sacrifice, even as wartime demands for output threaten the girls’ health.

A more detached conception of the Japanese spirit underlies The Men Who Tread on the Tiger’s Tail (1945). This adaptation of a plot from Noh and Kabuki theatre shows officers escorting a general through enemy territory. Disguised as monks, the bodyguards are forced to bluff their way through a checkpoint. The situation is one of hieratic suspense, made more tonally complex by Kurosawa’s addition of the movie comedian Enoken. Enoken plays a dimwitted porter reacting to the charade played out by his betters. By dramatizing one of the most famous episodes in Japanese literature, Kurosawa was reasserting the tradition of devotion to duty and honor. The Men Who Tread on the Tiger’s Tail was released the same month that the atomic bomb fell on Hiroshima.

During earlier decades, Japanese cinema had created a complex tradition. In part, it conducted a sustained dialogue with Western cinema. Tokyo had access to a wide range of Hollywood movies, and directors studied American technique closely. Just as Ozu would not be Ozu without his early fondness for Lubitsch and Harold Lloyd, Mizoguchi learned a good deal from von Sternberg. Between 1938 and 1942, alongside German imports Tokyo theatres screened Fury, Only Angels Have Wings, The Sea Hawk, The Awful Truth, Angels with Dirty Faces, Boys Town, Young Tom Edison, Only Angels Have Wings, and many French titles. In 1942, with Hollywood films now banned, one could still see René Clair’s Le Million and À Nous la liberté—films that had been circulating in Japan since the early 1930s and could have served as models of flashy sound technique. It’s misleading to talk of Ozu as “purely Japanese” and Kurosawa as “Western”: All Japanese directors of the 1920s and 1930s were deeply acquainted with Western cinema, and American cinema in particular furnished a foundation for most local filmmaking.

Yet there are crucial differences. Japanese cinema welcomed extremes of stylistic experimentation that would have been rare in Western cinema. The 1920s swordplay films (chambara) pioneered rapid editing, handheld camerawork, and abstract pictorial design. (I supply some examples here.) Directors working in the contemporary-life mode (the gendai-geki) experimented similarly, often achieving remarkable visual effects and bold stylization. Mizoguchi and Ozu have become our emblems of this creative rigor and richness, but they are the peaks of what was a collective approach to filmic expression. Not every film was an experiment—indeed, most behave like Hollywood or European productions—but many ordinary movies, signed by unheralded directors, exhibit flashes of unpredictable imagination. This was the tradition of permanent innovation that directors of the Kurosawa-Kinoshita generation inherited.

As the war dragged on, however, Japanese studio productions lost much of their audacity. Production fell from over 400 films in 1939 to fewer than 100 in 1943. Censorship may have made filmmakers cautious about style as well as subject and theme. Most of the fifty-plus films I’ve been able to see from the period 1940-1945 are quite conservative aesthetically. Several of these seem to me quite good, but they rely on fairly standard Hollywood technique sprinkled with touches that had become markers of Japanese cinema (sustaining scenes in rather distant shots, using cuts rather than dissolves to shift scenes, and so on). Swordplay films become more severe and monumental. Even Mizoguchi’s Genroku Chushingura (1941-42) and Ozu’s There Was a Father (1942), superb as they are, are more elevated in tone than the directors’ earlier works.

Against this backdrop, Kurosawa’s films stand out; they are the most extroverted works I know in this period. Their innovations remain vivid; Sanshiro Sugata, for one, with its hierarchy of competitors, its rivalry among schools, and its visceral technique, may have invented the modern martial arts film. But we should also realize that these early films build upon the traditions already firmly established in Japanese cinema.

Playing with the passing moment

Consider transitions. Kurosawa is famous for his elaborate links between sequences, from the hard-edged wipes to swift imagistic associations. But we should recall that transitional passages offer moments of flashy style in American and European cinema of the 1920s and 1930s, and indeed right up to this day. (For examples, go here and here.) In the same year as Sanshiro, Kinoshita gave us this moment in Blossoming Port. A con artist is trying to bilk money from a town. He bows, leaving an empty frame.

Without a discernible cut, heads pop into the empty frame, rocking to and fro.

Another cut reveals that the people we see are in a boat tossing on the waves, and the conman’s partner is enjoying an outing with the locals. Kurosawa’s scene-changes—sites of what Stephen Prince has called “formal excess”—can be seen as prolonged, imaginative reworkings of this tricky-transition convention.

Japanese filmmakers were more willing to play with the expressive and “decorative” side of filmmaking than most of their Western peers. Directors created not only flashy transitions but moments of stylistic playfulness within scenes. Sometimes this just adds to the overall tone of comedy, as in this pretty passage in Heiroku’s Dream Story, another 1943 release. The hero, played by Enoken, is squatting and talking to a charming girl (Takamine Hideko). She twirls her parasol between them, and we get a straight-on cut that creates a moment of abstraction as the parasol glides across the frame in contrary directions. (The vertical pair of frames shows the cut.)

This decorative symmetry would be rare in Hollywood outside a Busby Berkeley number, but it enlivens the characters’ exchange in a way similar to the more dramatic Rashomon sequence. To borrow a phrase that Kepler applied to nature’s way with snowflakes, a filmmaker may seek to ornament a scene by “playing with the passing moment.”

Likewise, in The Blossoming Port, as an older woman recalls a romance of her youth, the natural sound fades out and the back-projection behind the carriage shifts from the seaside to urban imagery of the period she’s remembering.

The frank artifice of this shot shows that Japanese filmmakers were eager to let us enjoy the forms with which they were working.

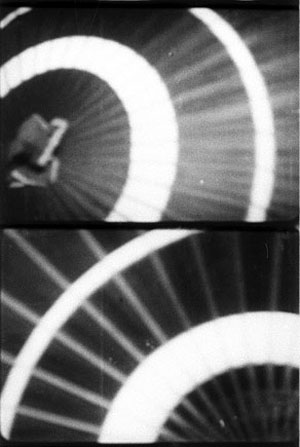

A similar explicitness about style can be seen in one of Kurosawa’s signature devices, the axial cut. This technique shifts the framings toward or away from the subject along the lens axis. If the shots are short enough, we sense a bump at the abrupt change of shot scale.

Kurosawa often uses this cutting to stress a momentary gesture or to prolong a moment of stasis. But it can structure a simple dialogue scene as well. In Sanshiro Sugata, the hero’s first conversation with Sayo takes place as they descend a stair toward a gateway. Kurosawa uses axial cuts to keep up with them as they move away from us down the steps. Illustrated with stills, this technique looks like a forward camera movement, but in fact these images come from separate shots.

The crux of the scene is Sayo’s revelation that the man Sanshiro must fight is her father, and instead of big close-ups to underscore his reaction, Kurosawa simply lets his hero halt while Sayo continues down the steps. The steady pattern of cut-ins to the characters’ backs makes Sayo’s sudden turn to the camera more vivid, and Sanshiro’s reaction is underplayed by not giving us direct access to his face.

An earlier entry traces theaxial cut back to silent film, when its jolting possibilities were exploited in Soviet montage cinema. Japanese directors also used the device often. Yamanaka Sadao, one of the most-praised directors of the 1930s, used axial cuts prominently in an early dialogue scene of Humanity and Paper Balloons (1937). The cuts are accentuated by low-height compositions that maintain the steep perspective of the street.

The technique gains more punch in Japanese swordplay films. Here is a percussive instance from Faithful Servant Naosuke (1939), four short shots yanking us inward in a way that Kurosawa would make his own.

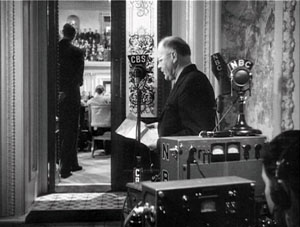

Tom Paulus reminds me that Capra films sometimes make use of this technique, as in this string of concentration cuts from Mr. Smith Goes to Washington (1939).

Interestingly, Mr. Smith ran on several Tokyo screens in October 1941; it may have been the last Hollywood feature to receive theatrical distribution before the attack on Pearl Harbor.

To say that Kurosawa adapts traditional devices doesn’t take away from his accomplishment. No artist starts from zero, and in commercial cinema, filmmakers commonly revise schemas already in circulation. So Kurosawa puts his own spin on the axial cut, not only by using it frequently, but also by varying it in the course of a film. Sanshiro Sugata 2 makes the axial shot-change a sort of internal norm, but then varies it: inward or outward, cuts or dissolves, how great a variation of scale? When Sanshiro leaves Sayo, the three phases of his departure are marked by simple repetition: each time he halts and looks back, she responds by bowing.

Like the Rashomon sequence, this shows Kurosawa’s fondness for permuting simple patterns. But there’s an expressive payoff too. The framings that make Sayo dwindle to a speck give the axial cuts the forlorn, lingering quality we usually associate with dissolves. In addition, for viewers who know Sanshiro 1, the scene calls to mind the staircase passage we’ve already seen. Their first extended encounter is paralleled by their last one.

Axial cuts are easier to handle when the subject is unmoving, or moving straight toward or away from the camera. What about other vectors of motion? In The Men Who Tread on the Tiger’s Tail, as the general’s bodyguards file out of the compound, they pass a line of soldiers in the foreground. Kurosawa combines concentration cuts with lateral cutting, so our men stalk leftward through the frame once, then again, then again, each time both closer to us and further along the row of soldiers.

Kurosawa revises other traditional techniques. You can find moments of extended stasis in swordplay films of earlier decades, and the technique surely owes something to the prolonged mie poses in Kabuki. But Kurosawa’s early films turn long pauses into living freeze-frames. Instead of using an optical effect, he simply asks his actors not to move! One combat in Sanshiro shows the audience caught in absolute stillness, staring at the result of Sanshiro’s throw. In Sanshiro 2, our hero and the boxer stand like statues in the prizefight ring until the American collapses. And in The Men Who Tread on the Tiger’s Tail, the groups gathered at the checkpoint are absolutely unmoving for nearly fifty seconds as Benkei leads them in prayer.

This shot’s tactful, reverential composition echoes a fairly standard image for showing loyal retainers; here’s an example from a 1910s version of Chushingura.

In sum, I think that for his “manly movies” Kurosawa sifted through the Japanese film tradition and pulled out the most vigorous techniques he could find, all the while recognizing that rapid pacing needs the foil of extreme immobility. He compiled a digest of many arresting visual schemas available to him, and then pushed them in fresh directions. He realized as well that he could apply this sharp-edged style to genres dealing with modern life.

A most stubborn young woman

Although we think of Kurosawa as a “masculine” director, two of his finest films center on women. The Most Beautiful and No Regrets for Our Youth can be thought of as propaganda, but this label shouldn’t put us off. Propaganda works partly because it taps deep-seated emotions, and I’d argue that the formulaic nature of a “social command” can allow filmmakers a chance at emotional and formal richness. Because the message can be taken for granted or read off the surface, an ambitious director can go to town—nuancing the presentation, complicating its implications, taking the clichéd message as an occasion for pushing formal experiment. (Which is one aspect of what the Soviet montage filmmakers did.)

The Most Beautiful, probably the best movie ever made about child labor, starts off as a doctrinaire effort. Before even the Toho logo fades in, a title declares: “Attack and Destroy the Enemy.” The first fifteen minutes are filled with pledges to help the war effort, work to meet an emergency quota, obey orders, display filial devotion, build noble character, and think constantly of how making flawless lenses saves soldiers’ lives. The rest of the movie focuses on the pain of doing all this. This story of patriotic affirmation is steeped in tears.

The film’s structure looks forward to the ensemble-based, threaded plotlines employed in Red Beard and Dodes’kaden. We follow various stories, if only briefly, as the teenage girls push themselves beyond the limits proposed by their overseers. The factory directors and the dormitory mother are barely characterized, so that the focus falls on the girls who have left their homes to serve their country. One looks out the window when a train passes; another walks sobbing across a garden made of heaps of earth from each girl’s native village. When one girl falls from a roof, she promises to keep working on crutches. Another hides the fact that she has a fever. In this movie, workers cry out “Mother!” in their sleep.

Sanshiro Sugata pulses with the exuberance of a young man’s body itching for constant movement. Kurosawa’s second film applies his muscular techniques to a static situation: Girls bent over machines. True, there are interludes of a marching and volleyball, the latter calling forth a standardized stretch of montage, but the director’s central task is to dynamize conversations. He finds a remarkable array of options. We get good old axial cutting, but there are also jump cuts (as if the action were too urgent to wait for dissolves), resourcefully simple staging (see this entry), abrupt close-ups, quick flashbacks, and judicious long takes jammed with actors.

Off on the right stand two tall girls frowning and looking down; their quarrel will burst out in a later scene.

The virtuosity here is quieter than in Sanshiro, largely because of the insistent threat of shame. A Hollywood film of the period might play up the triumphant achievement of the quota, but here this goal fades away. Instead, the plot is driven by a nearly desperate fear of failure. The men in charge offer bluff reassurance, but in a reprise of high-school nerves, the girls fret constantly about doing less than their mates. Their anxiety is translated into gesture-based performance—not through Western hysteria but through gestures of lowering the eyes, bowing the head, turning one’s back. The Most Beautiful has some of the greatest back-to-the-camera scenes in film history, and Kurosawa doesn’t hesitate to insert some of these moments in wide shots, creating a delicate emotional counterpoint. At one moment the girls are distracted by a passing airplane but their leader is sunk in thought; at another moment the girls challenge the leader while her accuser can’t face her.

The girls’ stories are woven around Watanabe, the section leader. Somewhat older than the others and nowhere near as spontaneous or joyous, she’s the emblem of unremitting self-sacrifice. If Sanshiro matures in the course of his films, learning the humbling responsibilities of becoming a supreme fighter, she comes to her more mundane task already grown up. Noël Burch has pointed out that Kurosawa’s protagonists are notably stubborn, and Watanabe offers a prime instance.

At the climax she has to search through thousands of lenses for a flawed one that she accidentally let through. Kurosawa forces us to watch her, exhausted from hours of work, hunched over her microscope and keeping awake by singing a patriotic song. One shot holds on her groggy efforts for over ninety seconds, so we register both the enormity of her task and her obstinate refusal to quit. This shot will be paralleled by the film’s final one, which lasts almost exactly as long, when she returns to her workbench. Now her concentration is broken, again and again, by quiet weeping. Kurosawa claims that when he made the film he knew Japan would lose the war.

The ending of The Most Beautiful calls to mind a moment in another Kinoshita film, again one released in the same year as Kurosawa’s. Army (1944) ends on a similarly ambivalent note, with a frantic mother pushing through a crowd cheering recruits marching off to war. Through cries of “Banzai!” she stumbles along to get a last glimpse of him, but soon her trembling figure is lost in the excitement. It isn’t exactly an exalted note on which to close a patriotic film.

A mother is central to Watanabe’s sacrifice in The Most Beautiful as well, and her plight reminds me of historian John Dower’s telling me that Japanese soldiers may have charged into battle shouting the name of the emperor, but many died murmuring, “Mother.”

Like other filmmakers, Kurosawa had to execute an about-face when the Americans came to occupy Japan. Along with Mizoguchi, Kinoshita, and most others, he began to make films that condemned the “feudal” forces that had led Japan to war and affirmed the need for liberalizing the society, not least with respect to women’s roles. Kurosawa’s contribution was No Regrets for Our Youth (1946), a survey of the 1930s and 1940s through the experience of a daughter of the middle class. At first she’s oblivious to the authoritarian threat and then, awakened to her social mission, she plunges into what we would now call the politics of everyday life. With the same verve that Kurosawa dramatized sacrifice for the motherland, he quickens a liberal fable of emerging political consciousness. Again, he finds ways of making propaganda deeply moving, while leaving his unique stamp on the project.

I hope to write about No Regrets and other Kurosawa titles in the future. But one implication should already be clear. Kurosawa remains on our agenda through his commitment to a mode of storytelling that pursues vigor without lapsing into the diffuse busyness of today’s spectacles. He stretches our senses through staccato action, yet he drills into other moments so implacably that we are forced to see deeper. He lifts certain Japanese and imported traditions to a new pitch, in the process often creating something indelible and enduring.

The point of departure for all things Kurosawa is Donald Richie’s Films of Akira Kurosawa, first published in 1965 and updated since. It was a trailblazing auteur study, written from deep knowledge of the films and many encounters with the director. Another indispensible source is Kurosawa’s Something Like an Autobiography (Knopf, 1982). Although it stops after the success of Rashomon, the book offers fascinating information about Kurosawa’s early life and first films. (“The Most Beautiful is not a major picture, but it is the one dearest to me.”) Information on the later films is collected in Bert Cardullo, Akira Kurosawa: Interviews (University Press of Mississippi, 2008). A biographical overview, with details on each film’s production, is provided in Stuart Galbraith IV, The Emperor and the Wolf (Faber, 2001).

For background on Japan’s wartime cinema, the central work is Peter B. High’s The Imperial Screen (University of Wisconsin Press, 2003). See also John Dower’s magnificent surveys of the war and the postwar period, War without Mercy (Pantheon, 1987) and Embracing Defeat (Norton, 2000).

Noël Burch argues that Kurosawa is best understood as working within a tradition of indigenous Japanese art; his pioneering To the Distant Observer (University of California Press, 1979) is available online here. Linking formal preoccupations to changing subjects and themes, Stephen Prince’s The Warrior’s Camera (Princeton University Press, 1999) argues that Kurosawa was forging heroic figures appropriate to developments in Japanese society. In Kurosawa: Film Studies and Japanese Cinema (Duke University Press, 2000), Mitsuhiro Yoshimoto puts the films in political contexts, while also considering how Kurosawa has been understood within the Western academy.

Critics have long recognized that Kurosawa’s formal inventiveness came with an impulse toward large statement. Brad Darrach reconciled the two tendencies in an overheated specimen of Timespeak:

Not since Sergei Eisenstein has a moviemaker set loose such a bedlam of elemental energies. He works with three cameras at once, makes telling use of telescopic lenses that drill deep into a scene, suck up all the action in sight and then spew it violently into the viewer’s face. But Kurosawa is far more than a master of movement. He is an ironist who knows how to pity. He is a moralist with a sense of humor. He is a realist who curses the darkness—and then lights a blowtorch.

This comes from “A Religion of Film,” a remarkable primer on the art cinema in its American spring. It was published in Time of 20 September 1963 and is available here. The same antinomy of stylist vs. moralist persists, with less complimentary results, in Tony Rayns’ obituary in Sight and Sound (October 1998), p. 3 and in Dave Kehr’s recent review of the Criterion boxed set.

I wrote about Kurosawa’s work in our textbook Film History: An Introduction (third edition, McGraw-Hill, 2009), pp. 234-235 and 388-390. My larger arguments about classic Japanese film can be found in Ozu and the Poetics of Cinema (online here) and in two articles in Poetics of Cinema (Routledge, 2008), “A Cinema of Flourishes: Decorative Style in 1920s and 1930s Japanese Film” and “Visual Style in Japanese Cinema, 1925-1945,” which analyzes some of the films I’ve considered here. I talk a little more about editing in Seven Samurai in this entry. In another I discuss how Kurosawa’s “humanism” fits into one 1950s ideological framework.

Yamanaka’s Humanity and Paper Balloons is available on DVD in the Eureka! series. For a cinematic homage to early Kurosawa, see Johnnie To’s Throw Down.

Thanks to Komatsu Hiroshi for supplying the date of Faithful Servant Naosuke. And as a PS, thanks to Luo Jin for pointing out a “slip of the finger”: the original post had Kurosawa older than Ozu!

PPS: 9 December: The Criterion site has just posted a reminiscence of Kurosawa by Donald Richie.

PPPS: 15 May 2010: Criterion has just announced that the four films discussed in this entry will be released as a separate collection on the Eclipse label.