Archive for 2009

(50) Days of summer (movies), Part 1

Ponyo on a Cliff by the Sea.

DB here:

Travel took me out of Madison for half of June and nearly all of July. While overseas, I saw only one recent US release. So I caught the American Summer Movies in two gulps–over a couple of weeks early on and over the last month or so. In all, exactly 50 days? Well, were there exactly 50 first dates in that movie?

Herewith, comments on a batch of titles. There are spoilers sprinkled throughout, but most of what I say won’t harm your encounter with the film. Because all my remarks amounted to an even longer blog than usual, I’ve broken it into two parts. The next installment, coming up in a few days, talks about The Taking of Pelham 123, Public Enemies, and Inglourious Basterds.

My summer movies were bracketed by two animated pictures. Up is to my mind the most mature Pixar film yet. It has all the virtues we associate with this studio: quick but not frantic pacing, expert handling of resonant motifs, technical brilliance (especially in its depiction of settings), and one-off gags. The poker-playing dogs had me laughing out loud. But as we’ve argued in other blogs (here and here and here), the Pixar team likes to set itself tough challenges. First there is the technical challenge of 3-D, which is easily surmounted. The 3-D effects get more pronounced once the plot lands in South America. More important, I think, is the challenge of representing the emotion of sorrow.

Another movie would have organized its plot around the kid, Russell, and let him meet the elderly Carl in the course of his adventures. That way, Carl would emerge as a merely touching secondary character. But by focusing point of view around Carl’s life, showing his marriage and widowhood, Pete Docter and his team have tackled one of the hardest problems of classic moviemaking. How do you render pure sentiment without becoming sentimental?

The protagonist’s portrait is surprisingly hard-edged. Carl is tightly wound even in his youth, unlike the exuberant and extroverted Ellie. Yet the couple seems to have no friends throughout their marriage, and it becomes easy to see how Carl could will himself into crabby isolation after her death. Thanks to the choice of viewpoint, Carl becomes no mere crank but a truly empathetic figure.

This is fragile stuff, and Docter handles it with tact. Many movies want you to cry at the end, but Up daringly invites you to indulge in its first ten minutes. It then spends the rest of its running time brightening your mood, so that the title could describe the film’s emotional trajectory. It’s one of my two favorite new movies I saw this summer.

Just a few days ago Kristin and I saw Ponyo on a Cliff by the Sea. We’ve been Miyazaki fans since Totoro, and have especially admired Kiki’s Delivery Service and Spirited Away. As with this last and with Howl’s Moving Castle, I have a hard time figuring out the premises of the plot. What rules govern Ponyo’s transformations? Why can’t she become a real girl, exactly? And then why is she permitted to? The well-timed interventions of her mother, like the Witch’s change of heart in Howl, seems a way out of plot difficulties, and as often happens in Miyazaki the plot resolution seems rushed in comparison with the leisurely development of characters’ relationships.

But as usual I was won over by the effortless virtuosity of the imagery and the weird conviction suffusing Miyazaki’s concept of nature. As in Spirited Away, animation becomes animistic. The sea is bursting with hidden forces: goldfish with extraordinary powers of group effort, waves that turn into blue fish, and bubbles as solid and slippery as balloons. Nobody but Miyazaki could imagine the quasi-Wagnerian scale of Ponyo’s race, atop gigantic fish-waves, to catch up with Sosuke and his mother fleeing in their car.

These shots burst with more dynamic shifts of mass and scale than I’ve felt in any official 3-D picture.

Sometimes Nature is scary. Although nothing here is as traumatic as Spirited Away‘s transformation of parents into swine, the tsunami scenes induce genuine awe at nature’s exuberant destructiveness. There follows a reassuring calm. Ponyo and Sosuke glide along the flood waters while ancient creatures zigzag in the depths, and the townspeople quietly accept that their homes have been engulfed. Ponyo is a gentle movie, aimed (as Miyazaki explains here) at a younger audience than was his recent work. It’s suffused with simple human affection, seen in acts of spontaneous generosity. What American movie could include a moment when Ponyo, fish become girl, offers a nursing mother a sandwich to help her make milk for her baby? Again, sentiment without sentimentality. Ponyo offers more evidence that whatever the disappointments we may find in live-action movies, we are living in a golden age of animation.

Am I just being perverse in finding Transformers 2: Revenge of the Fallen not as abysmal as others have? Don’t get me wrong. It is not what you’d call good. It is rushed and overblown. What other movie accompanies its opening company logos with gnashing sound effects? Its plot is even more preposterous than the first one’s. Its performers bear that sheen of meretriciousness that fills nearly every Michael Bay project. It is also lazy in its plotting. Worse, I couldn’t really make out the design of the ‘bots. It’s not that the cutting is abnormally swift (a mere 3.0 seconds ASL, about the same as in Up and slower than that in The Hurt Locker). The problem is that the digital camera is swirling around the damn things so fast as they take shape that you can’t get a fix on what they actually look like. All those spinning wheels and dangling carburetors ought to be worth a glance.

But still….For non-Transformers shots Michael Bay at least puts his camera on a tripod, which these days counts as a plus with me. And a minibot humps the heroine’s leg. And John Turturro is in it. Would he grace a movie that signals the fall of Western Civilization?

In a similar vein but more satisfying was District 9. Its “racial subtext” is as perfunctory and confused as such weighty hidden meanings usually are, and anyhow whatever political points the movie wants to make drift out of view halfway through. Moreover, its “documentary immediacy” is inconsistent: despite footage marked as coming from surveillance and TV cameras, we have unimpeded access to all plot matters. But here the Bumpicam probably allows for cheaper CGI, and as a run-around-shooting-things movie, it needs to keep things simple.

In a similar vein but more satisfying was District 9. Its “racial subtext” is as perfunctory and confused as such weighty hidden meanings usually are, and anyhow whatever political points the movie wants to make drift out of view halfway through. Moreover, its “documentary immediacy” is inconsistent: despite footage marked as coming from surveillance and TV cameras, we have unimpeded access to all plot matters. But here the Bumpicam probably allows for cheaper CGI, and as a run-around-shooting-things movie, it needs to keep things simple.

I found the smash-and-grab look far more distracting in The Hurt Locker. Kathryn Bigelow has directed several first-rate movies, notably Near Dark (where she used a tripod), Blue Steel (ditto), and Point Break (tripod mostly). On this project, she seemed to me to be doing more conventional work. There are the titles telling us that time is running out (“16 Days Left”). There’s classic redundancy of characterization, as when we’re told that James is a hot dogger–“He’s reckless!” “You’re a wild man!”–as we watch him be all that he can be, and more. There’s the hapless kid who is so near to the end of his tour that you know he’s a marked man. There are even aching slow-mo replays of explosions bowling guys to the camera. What if war films gave up this convention and just showed bombs going off and bodies hurled around as fast as in reality? Might war look a little less picturesque?

The camera is locked down for these iconic slow-mo shots, but most of the scenes are handled in heat-seeking pans, artful misframings, chopped-off zooms, and would-be snapfocusing that can’t find something to fasten on. The editing plucks out bits of local color and sprinkles in some glimpses of onlookers that tend to turn them into props. I’ve tried to show elsewhere that this trend in rough-hewn technique nonetheless adheres to the conventions of classical style: establishing/ reestablishing shots, eyelines, reactions, and close-ups to underscore story points. Even wavering rack-focus can still orient us to the action quite clearly.

The question is what the harsher surface adds, especially when it’s so pervasive. Habituation is one of the best-proven phenomena in psychology, and movies like this seem to prove that it works. After the first few minutes, we’ve adapted to any visceral punch that the Unsteadicam hopes to provide. Maybe it serves to ratchet up suspense? Doubtful. A director would have to be a real duffer to dissipate suspense in a movie about dismantling an explosive device. The trick is to do something different, as in bomb-disposal movies like the Chinese Old Fish and the British Small Back Room.

Still, the plot is decently engaging, and there’s a taut, unpredictable siege in the desert. That long sequence displays a disciplined interplay of optical viewpoints, a sense of constantly revised tactics, a new aspect of James’s leadership style, and nice details about sharing juice boxes. In another era, The Hurt Locker would have been a studio picture in the vein of Anthony Mann’s bleak Men in War. I suppose it shows that yesterday’s genre film, executed with conviction and a certain edginess, can become today’s art movie.

Speaking of suspense: I thought that the setup to A Perfect Getaway was reasonably engrossing. There was some clever self-referential teasing: our hero’s a screenwriter, and there’s talk of a “second-act twist.” And it was mostly shot on a tripod. I hoped that director-writer David Twohy would have the courage to stick with its initial premise and be Deliverance in Hawaii. But sure enough, the things that smelled like red herrings were red herrings, and the reversal that you feared comes to pass in one of those point-of-view switcheroos that movies now indulge in. Come to think of it, that was the second-act twist. But I did like the strategically placed telemarketer call.

We’re evidently allotted one crossover indie movie per summer, a fact acknowledged in the title of this year’s hit. (500) Days of Summer, which really needs its parentheses not just because everybody now overuses them (there’s even a blog confessing it), but because its strategy is to disarm you with its knowing cuteness. It is so self-consciously winning your teeth will ache. It’s a twentysomething romance of the sort usually called “bittersweet.” The guy’s after love and the girl withholds commitment. Guaranteed result: emotional roller coastering, because we’ve seen her flighty sort before in kooky-girl figures like Petulia. There’s a fantasy musical number with a touch of animation, an avuncular narrating voice sliding in and out, a shuffled time scheme sorted out for us with a sort of daily odometer reading, and pop-culture references including retro ones to The Graduate and Ringo Starr. Everybody smiles a lot, and when they’re not smiling they’re crinkling up their faces.

(500) Days plays by the book. Tom and Summer work for a greeting-card company, a satiric target only a little harder to hit than the Pentagon. As in the movies mentioned above, the cutting is intent on making sure we see everybody deliver every syllable. (What ever happened to offscreen dialogue? Did TV kill it?) (Sorry about the parentheses.) The four-part script layout is as neat as embroidery: the first kiss at the photocopiers comes at 24:00, the splitup comes at 47:00, Tom delivers his diatribe against the lies about love at about 72:00, and the epilogue, with its fatal final line, finishes at 90:00. Yet I’m not curmudgeon enough to despise a movie so desperate to be liked, and at last I found a film whose narration clicks along in syncopation with my little tally counter.

The real indie film I admired in my fifty days was Ramin Bahrani’s Goodbye Solo, or Good Bye Solo as the credit title has it. Kristin and I have registered our admiration for Bahrani’s films here and here on this site, and his latest is no less modest, well-crafted, and affecting. A Senegalese emigre cab driver befriends an enigmatic old man who at the start of the film offers him $1000 to pick him up on October 20 and drive him to Blowing Rock Mountain. Solo infers that William is planning a suicide and so starts to intervene in his life. His involvement with William gets intertwined with his family problems and his hopes of becoming an airline attendant.

Goodbye Solo exemplifies the “character-driven” movie. Solo is sunny, quick-witted, and socially adroit; his audition for the airline managers shows him as an ideal employee. William is just the opposite–morose, aggrieved, profoundly unhappy. The treatment is observational, with lengthy shots (an average of over twelve seconds) capturing dialogue and slowly shifting character response.

The characters change, but Bahrani and his co-screenwriter Bahareh Azimi, wary of quick fixes, don’t push this too far. It would be easy to make William soften more, even eventually make him likeable, and to keep Solo an indefatigable force for optimism. Instead, if William accepts more of Solo’s ministrations, it’s largely due to his passivity, not a fundamental change of heart. Meanwhile, Solo becomes more anxious and pessimistic, shedding some of that casual charm that captivated us in the opening. Neither executes that neat character arc that Hollywood tends to favor and that’s visible in Up and (500) Days of Summer.

The characters change, but Bahrani and his co-screenwriter Bahareh Azimi, wary of quick fixes, don’t push this too far. It would be easy to make William soften more, even eventually make him likeable, and to keep Solo an indefatigable force for optimism. Instead, if William accepts more of Solo’s ministrations, it’s largely due to his passivity, not a fundamental change of heart. Meanwhile, Solo becomes more anxious and pessimistic, shedding some of that casual charm that captivated us in the opening. Neither executes that neat character arc that Hollywood tends to favor and that’s visible in Up and (500) Days of Summer.

Bahrani’s hatred of cliché obliges him to make his story events mundane and equivocal. As in Man Push Cart and Chop Shop, the plot emerges from variations in routine, a lesson well-taught by European festival cinema of the 1950s. But when you have a stubborn, taciturn character like William, and you’re restricted to another character’s range of knowledge, it’s hard to give the film a forward propulsion. You have a deadline, but no momentum. So plot dynamics arise from Solo’s relation to his wife and daughter, his career goals, and above all his investigation of William’s past–his search for what could drive the man to suicide. And this investigation turns on conveniently discovered clues.

Someday I must do a blog entry on tokens in narratives. Any plot of some complexity seems to need physical objects that encapsulate dramatic forces, spread out information, or become emotion-laden motifs. The photograph is probably the most traditional one, but notes, diaries, rings, and so on are useful too. In Goodbye Solo, William’s tokens move the drama of disclosure forward, and it’s possible to object to the film’s reliance on so many of them.

The problem Bahrani faces is that the film has to give us personal information about William while retaining tact and respect for characters’ integrity. For William to open up into a Tarantino-style confession would tear the movie apart; even a quiet moment of sobbing vulnerability is too indiscreet here. The film needs its tokens, however awkward they may seem as narrative devices, to keep faith with its people.

Staying a little outside the characters, allowing them to retain some private motives, is exactly what (500) Days of Summer doesn’t attempt. Bahrani’s discretion extends to the very last scene. The title becomes a line that someone should speak but doesn’t. Up till now, the quietly precise images have been shot by a camera locked down, but atop a mountain the camera leaves its tripod and supplies some mildly shaky imagery. And now it fits. It’s not just that the drama has reached an emotional pitch. The camera is simply buffeted by the wind. Once more Bahrani lets his world do its work.

You can read about our summer film-related travel here and here and here and here and here.

Overwhelmed by all the material on Pixar and Up, I merely point to two encyclopedic experts: the ever independent-minded Mike Barrier and the always-informative Bill Desowitz, who offers information on Pixar’s approach to 3-D here. For Ponyo background and an interview with Miyazaki, turn again to Bill D, here; he provides a transcript of a conversation between Miyazaki and John Lasseter here. A fat book of Miyazaki interviews and essays has just been published, and it includes some incendiary stuff, such as “Everything that Mr. Tezuka [Osamu, the ‘god of animation’] talked about or emphasized was wrong” (197).

The parentheses in (500) Days of Summer are explained by screenwriter Scott Neustadter at Jeff Goldsmith’s Creative Writing podcast.

Roger Ebert has reviewed nearly all these films and as always he has sensitive things to say, particularly on Goodbye Solo. He’s been championing Bahrani’s films for many years and he offers a warm career appreciation here.

Goodbye Solo.

Archie types meet archetypes

DB here:

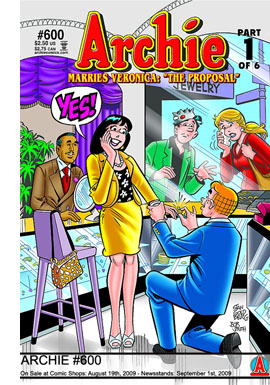

You heard about it in May, but the proof arrived in comic-book stores just lately. Archie has proposed to Veronica. At the midpoint of issue #600, he goes down on bended knee in Spiffany’s and pops the question.

The rest of the issue is devoted to other characters’ reactions. Mr. Lodge, at first outraged, says that Archie must come to work for him. Jughead is judgmental but ultimately forgiving, in his droopy-eyed way. Archie’s parents are delighted. Even Reggie shows a dash of gallantry. All of Riverdale is buzzing, but over the joyous news hangs a cloud of worry.

What about Betty?

She accidentally witnessed the proposal and at first broke down uncontrollably. Later we see her as surprisingly stoic—until she gets a phone call from Veronica (cruel? compassionate?) asking her to be maid of honor. The installment ends with Betty forlornly telling Veronica, “You—you won.”

She accidentally witnessed the proposal and at first broke down uncontrollably. Later we see her as surprisingly stoic—until she gets a phone call from Veronica (cruel? compassionate?) asking her to be maid of honor. The installment ends with Betty forlornly telling Veronica, “You—you won.”

DON’T MISS THE STORY THE WORLD HAS BEEN WAITING MORE THAN 60 YEARS TO READ! we read on the last page. Part Two, “The Wedding,” will follow next month, with four more parts after that. Archie Comics Publications has promised future episodes in which Arch and Ronnie procreate.

On her blog, Veronica is more or less gloating. Betty seems to have come to terms. On her blog she wrote:

What can I say? It is so sad.

Xoxoxoxo

Bets

Still, Betty suggests she feels the sting of mockery, and we can expect more pain in her future. Fan reaction has been far more furious. Mackenzie writes:

ARCHIE SHOULD HAVE MARRIED BETTY!! I MAY ONLY BE 10 BUT HE MUST MARRY BETTY. HOW COULD HE BE SO STUPID. I THINK HE IS TRYING TO BE RICH. POOR POOR BETTY.

One devotee, proprietor of a comics shop, sold his copy of Archie #1 in protest, and the $38,000 it fetched has not assuaged his discontent.

Like all boys I knew, I preferred Betty to Veronica. So I join in the mourning, and not just because it promises a sad married life for Arch. This upheaval threatens to destroy the Riverdale we loved. Betty working in a shop in Manhattan, Reggie in Atlanta selling cars, Moose running a burger joint in Staten Island: All dismally realistic options for today’s grads, but that’s small consolation. And what about Miss Grundy and Mr. Weatherbee and Pop Tate? Have we no cares for them?

In this crisis, panic is understandable. Yet I believe that older heads have a duty to assume leadership and calm the younger, more tempestuous spirits. A careful reading—well, okay, just a simple reading—of fateful issue #600 gives us a glimmer of hope. It also illustrates how a very old narrative convention can be revamped in popular culture.

A man of many parts

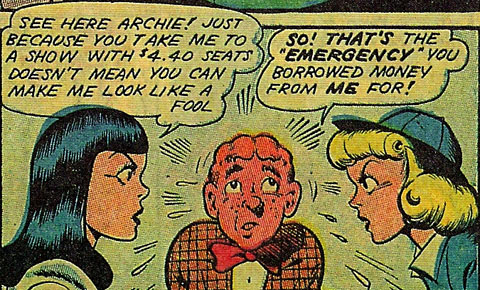

My acquaintance with the Archie series goes back to the mid-1950s. The books had already moved from the 1940s caricatural portrayal of Riverdale’s residents (above) to a more streamlined look reminiscent of Hergé’s clear line style.

Eventually the visual style would become still more minimal, offering little shading or detail and relying on a smaller repertoire of facial types, expressions, and gestures.

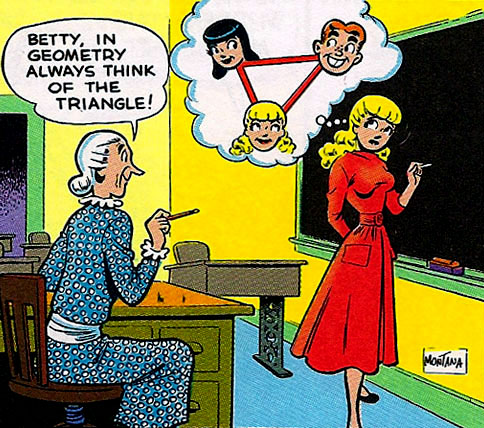

What I didn’t know then was that the first series artist, Bob Montana, was a gifted storyteller who made shrewd use of the graphic shorthand that adds so much to comics. In “Double Date” (#7, 1944), the issue that established the Eternal Triangle, Archie has wound up taking both girls to the same play. Of course neither knows that her rival is there. Archie escorts each one into the theatre and then races between Veronica in the orchestra and Betty in a distant balcony. Montana crisply renders Archie and Betty climbing past ushers to the nosebleed seats. Interestingly, this stack of panels must be read from bottom to top.

Archie races downstairs to check in with Veronica, and the swirl of his descent wraps inside the circular frame like baseball stitching. A horizontal stripe using the vertical panels’ green tone demarcates the movement between floors.

Once Betty discovers Archie’s perfidy, she stalks off, and Montana combines the two earlier framings, circle and square, yellow and green, in showing their zigzag descent.

Morover, in a story based on symmetries, each girl’s discovery of Archie’s perfidy is given a canted deep-focus framing that Orson Welles might have liked.

I wish I could find this sort of pictorial ingenuity in Archie #600, but like most of the 1950s and 1960s entries I’ve reread, this one is all about story. And fairly comedy-free story at that. Years ago boys like me followed Archie, but I suspect that now the prime readership is tween girls, so the romance-based pathos of Betty’s suffering may hit its target audience. Still, what the issue lacks in graphic sophistication may be made up for in its use of a narrative device that has become salient in popular culture, including movies.

The road not taken

In Poetics of Cinema I included an article called “Film Futures.” Originally a paper for a 2001 conference, it sought to analyze an emerging trend in filmic storytelling that has its roots in folktales and popular literature. That is the device of the hypothetical future.

The most famous example in literature probably remains A Christmas Carol, in which a ghost confronts Scrooge with a harrowing vision of his fate if he does not mend his ways. Dickens’ story showed how an alternative-future plot could be motivated by the supernatural, still a common way to show an alternative course of events. Later writers would rely on hallucination or science-fiction premises, such as time travel that allows a return to a point of choice. At various periods, films have drawn on these principles, from The Love of Sunya (1927) to Back to the Future II (1989). There are unmotivated instances of alternative futures as well in plays by J. B. Priestley, novels by Allen Drury, and art-comics by Chris Ware.

The central premise of this device goes back further. Many folktales from various cultures present brothers halting at a crossroads. Each brother picks a different road, and the plot is built out of their contrasting fates. Sometimes each road is marked with an enigmatic prediction about what will happen further along. O. Henry picked up the motif in his audacious 1903 story “Roads of Destiny,” which presents a single protagonist hypothetically taking each path in turn. His fate catches up with him whether he chooses one road or the other or just returns home.

In my essay I explore how the idea of forking-path futures was revived on film in Kieslowski’s Blind Chance (1987), Tykwer’s Run Lola Run (1998), Peter Howitt’s Sliding Doors (1998), and Wai Ka-fai’s Too Many Ways to Be No. 1 (1997). The essay aims to show how this plot formula, so apparently free-form, relies on a set of firm conventions. For example, in principle the character might have an indefinitely large set of fates, but the first parallel universe presented sets the premises–characters, issues, and the like–that will be varied in the other alternatives. The conventions, I argue, allow the filmmakers to establish a surprisingly narrow set of options, but this trains us to notice fine-grained differences.

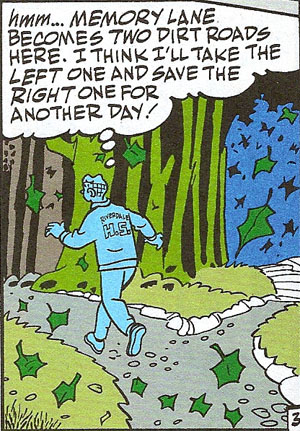

Archie’s proposal to Veronica, we learn, takes place in just such an alternative future. The present time of the narrative in issue #600 is the night of Archie’s last high-school rock concert. But Archie, facing the need to apply to college, goes out for a walk. He arrives at Memory Lane. Instead of walking down the lane—that is, into the past—he walks in the opposite direction, into the future. Suddenly he’s encountering his parents on the night of his graduation from college. A title intervenes.

Stop the presses! Did Mr. Andrews say Archie was graduating from COLLEGE? What happened to HIGH SCHOOL? By walking up Memory Lane, has Archie walked into his own FUTURE?

In short, yes. Everything we encounter from here on takes place four years after the initial scenes. Archie’s proposal and Betty’s fraught response are set in the future, as presumably will be the wedding and the eventual birth of Archie’s and Veronica’s children.

Already, then, there’s a way to set things right in Riverdale. That’s to change the future, to treat it as only one possible line of action. And in taking Archie up Memory Lane our plotters have relied on the folk archetype I’ve just mentioned.

This is quite a tease. The motif of pairs that we saw in “Double Date” returns with a vengeance. (A propos, it’s announced on the Internets that Archie and Veronica will have twins.) More important, the presence of a second road suggests that Archie has another future, one in which he doesn’t propose to Veronica. This device allows Arch to retreat at any time back along Memory Lane, and then back to the choice-point. Maybe there he will take the “right” road and eventually choose Betty? And is it an accident that the road on the left, drawing him toward marriage to Veronica, takes him into a gloomy forest, while the other one, paved in white stones, leads to a blue sky?

So the narrative leaves an escape hatch: Arch could retreat to this fork. Or he might even decide that he doesn’t want to know his other fate. In which case he could go back down Memory Lane, pass the point he entered, go further back in time, and return to his high school days, putting college—Archie a history major?—into a fuzzy future. But plot it yourself. Or follow the developments through the next five months.

Archie #600 may be offering its young readers a tutorial in understanding alternative-future plots–hence the redundant explanations in the panel quoted above. Historically,though, it’s behind the curve; the recent vogue for forking-path plots seems to have passed. Why did such plots become more common around the turn of the last century? We might invoke Steven Johnson’s argument, in Everything Bad Is Good for You, that audiences got smarter, so narratives became more complicated. Other students of “puzzle films” want to trace such narrative hijinks to postmodernity; no surprise there.

My own explanations can be found in the essay, where I look to factors like modern media’s intense demand for novelty, the quick spread (and exhaustion) of narrative innovations, and most specifically the conventions of storytelling established in things like branching-tree video games and the Choose Your Own Adventure books. Whatever the causes, at any point in history, very old narrative techniques lie waiting to be dusted off and given a fresh polish in the popular arts. Even Archie, going on seventy and still technically a bachelor, can get a makeover.

Archie Comic Publications has its website here. The story “Double Date” is reprinted in Charles Phillips, Archie: His First 50 Years (New York: Artabras, 1991), 34-44. An early published version of my “Film Futures” piece is here via library access, but the revised and expanded version in Poetics of Cinema is preferable. The “choice-of-roads” device is N122.0.1 in Stith Thompson’s Motif-Index of Folk Literature. It is discussed in Archetypes and Motifs in Folklore and Literature: A Handbook, ed. Jane Garry and Hasan El-Shamy (Armonk, NY: M. E. Sharpe, 2005), 333-341.

P.S. 14 August 2010: Archie’s multiple futures were only the beginning of a major rebranding effort.

P.P.S. 23 January 2017: Turns out that Forking-Paths Archie was a turning-point for both the hero and the company. See this fascinating Vulture story.

Has 3-D already failed?

Kristin here–

Years ago, James Cameron announced that his upcoming film, Avatar, would only be released to theaters capable of showing it in 3-D. Since then, he has proselytized fervently at trade shows and fan cons, hoping that Avatar would be such a blockbuster that exhibitors would finally decide to make that expensive leap and invest to convert their auditoriums to add 3-D.

Many commentators seemed to assume that Cameron’s saying such a thing would make it so. Here’s what Popular Mechanics opined only a little over a year ago:

Cameron’s insistence on 3-D projection will likely force the industry to ramp up the installation of 3-D technology dramatically. “Cameron is going to be able to bully theaters into compliance,” says former Premiere magazine critic Glenn Kenny. “He’s got the clout, and he’s got the mojo to do it. Everybody is going to want his next film.”

Avatar will need about 4,000 screens for a 3-D-only release, estimates Doug Darrow, manager of DLP brand and marketing at Texas Instruments, which makes the chips that power theatrical 3-D projectors. Of course, once the Avatar-inspired infrastructure is in place, other 3-D-only releases will follow.

The problems with conversion are manifest. Number one is the expense. 3-D systems are digital, so first the theater owner must convert from 35mm projectors to digital. 3-D is an add-on system that entails additional expenditure. A digital conversion alone costs over $100,000, about five times the cost of a 35mm platter projector. Right now most “D” theaters have 2K projection, but 4K is gradually being introduced for both shooting and showing. (Che and District 9 were shot mostly on 4K.) What theater owner wants to buy an expensive projector that will be obsolete within a few years? And what was supposed to be the breakthrough year for 3-D sees us at what may be the bottom of a huge financial crisis. It has slowed down an already laggardly process.

Among commentators, there’s apparently a lot of support for Cameron’s position. This year, coverage of Avatar has been considerable and has mostly echoed his prediction that this is the future of cinema. Geeks who tend to love special-effects-heavy sci fi and fantasy films also tend to long for all of those films to be 3-D. Star Wars and The Lord of the Rings cannot be converted into 3-D fast enough for them. They run websites to express their fervor and to report every new technical innovation and every rumor about a future film perhaps being made in 3-D.

I’ll admit that the signs that 3-D is finally going to become a routine and frequent method for making and exhibiting films are clearer than ever this year. More theater chains are announcing conversion to digital projection after years of resistance. More films in 3-D, and good films, are appearing, like Coraline and Up. And I have to admit that I enjoyed Monsters vs. Aliens more than its tepid reviews had suggested I might.

But there are negative signs as well. Perhaps most notably, the major proponents of 3-D, after years of berating the exhibition wing of the industry for its slow adoption of digital and 3-D technology, are still berating it. Jeffrey Katzenberg, who had announced that all Dreamworks Animation features would henceforth be made in 3-D, is one such complainer. Cameron is another. As of now, roughly 320 of the U.K.’s 3600 screen are digital—which doesn’t entail that all have 3-D capacity. In the U.S. it’s 2500 out of 38,000.

These days, a major blockbuster may open on 4000 screens or more. Given Avatar’s massive budget, rumored at $237 million (not counting prints and advertising), Twentieth Century Fox couldn’t settle for showing only in 3-D, even if every properly equipped screen in the country showed it.

The recent theatrical free previews of scenes from Avatar in 3-D have renewed the claims that this approach is the future. Yet some commentators are cautious about that claim. The Guardian quotes Louise Tutt, deputy editor of Screen International: “It seems a little overambitious,” she says. “A little over-enthusiastic. I mean, take a film like 4 Months, 3 Weeks and 2 Days – who needs to see that in 3-D? So no, I don’t believe it will happen.” She sighs. “But then who am I to contradict James Cameron?”

Cameron is a mighty force for change, no doubt. The Abyss and Terminator 2 introduced the sort of morphing technology that made digital effects a reality. But oddly, there aren’t a lot of other directors quite that gung-ho about 3-D. They’re willing to praise it and suggest that they may make films in 3-D, but they don’t go around to trade shows pressuring exhibitors to convert their theaters.

Peter Jackson, for example, keeps hinting at such a possibility. Apparently his team is testing the new Red camera’s 3-D model with an eye to using it in the remake of The Dambusters. That’s slated to be produced by Jackson and directed by Christian Rivers. But if Jackson were as enthusiastic about the process as Cameron, wouldn’t The Lovely Bones be in 3-D? Steven Spielberg hasn’t been pushing 3-D, although there are rumors about the Tintin films being 3-D. But rumors and expressed interest don’t influence exhibitors reluctant to invest in upgrading theaters on the basis of the still-limited 3-D product that’s out there so far. Where’s Ridley Scott in this debate? Well, to be fair, he called the Avatar footage “phenomenal,” but I don’t see him making 3-D movies and demanding that they play only in properly equipped theaters. Where’s Tim Burton? Even George Lucas, Mr. Digital Technology, who keeps saying that Star Wars will be converted to 3-D, doesn’t have Cameron’s zeal.

Retro-fitting movies is hugely expensive, by the way. One of the few retro-fitted titles, Tim Burton’s The Nightmare before Christmas, has taken to returning annually, as if to remind us of that fact.

Even Pixar, which has said it will henceforth make all its films in 3-D, has been strangely low-key about its current project of re-doing the first two Toy Story films in 3-D and re-releasing them as a lead-up to the premiere of the third film, planned in 3D from the start. (This year the first two will be shown at the Venice film festival, which has added a 3-D prize.) Presumably they are content to provide both 3-D and 2-D prints.

We’re also not seeing a lot of directors in other countries clamoring for the option of making their movies in 3-D. Hollywood may dominate world cinema in terms of screen time occupied and tickets sold, but there are still thousands of movies made elsewhere each year.

There are still few enough theaters in the U.S. capable of showing 3-D movies that films end up with truncated runs. Coraline perhaps suffered most from being taken off screens while it still had commercial potential and before word of mouth had time to help it gain the audiences it deserved. The release of the partially 3-D Imax version of Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince was delayed by the fact that Transformers 2 was still occupying Imax theaters. I can’t help but wonder if there are some studio executives who look at this situation and, without announcing it to the world, decide that the films they’re about to greenlight will be made in 2-D. Plenty of those theaters to go around. (Well, not for all the independent films jostling each other in the market, but that’s another blog topic.)

Cameron has bowed to the inevitable and is allowing Avatar to play in both 3-D and 2-D theaters. It seems obvious that it will still take years before a film can go out into the world without 2-D 35mm prints being included in its distribution.

During those years, there’s the potential that 3-D will lose its luster for audiences. One of the main arguments always rolled out in favor of conversion is that theaters can charge more for 3-D screenings. Proportionately, theaters that show a film in 3-D will take in more at the box-office because they charge in the range of $3 more per ticket than do theaters offering the same title in a flat version.

But what happens when, say, half the films playing at any given time in a city are in 3-D? Will moviegoers decide that the $3 isn’t really worth it? Even now, would they pay $3 extra to see The Proposal or Julie & Julia in 3-D? The kinds of films that seem as if they call out for 3-D are far from being the only kinds people want to see. Films like these already make money on their own, unassisted by fancy technology.

Then there’s the fact that the extra $3 is not simply profit. There has to be an employee handing out the glasses, though sometimes the ticketseller does that. And those glasses in themselves cost money. Some will get damaged. When David and I saw Monsters vs. Aliens, there was a woman with a child, perhaps four years old, in front of us in the concession line. She handed both pairs of glasses to the kid while she dealt with paying for the refreshments. He had his fingers all over the lenses, of course.

If a theater is using the RealD 3-D system, it’s no big deal if kids with sticky fingers get hold of the glasses. They are so cheap as to be disposable, if the theater doesn’t want to bother collecting and re-using them. Problem is, the theater has to buy or rent a special silver screen to project on. The Dolby 3D system doesn’t require a special screen, but its glasses cost a whopping $50 apiece as of 2007. In Dolby theaters, you’ll find tense ushers waiting outside, making absolutely sure everyone returns theirs for washing and re-use.

[September 9: A Dolby representative informs me that the cost of the company’s glasses is currently $27.50, well as this information:

- The Dolby 3D glasses are high-performance, eco-friendly passive glasses that require no batteries or charging and can be reused hundreds of times without sacrificing image quality.

- The environmentally friendly and reusable glasses can be used repeatedly, significantly reducing the cost down to cents per pair per screening for exhibitors.

Thanks, Erin.]

No doubt 3-D enthusiasts would object that someday the system will be so routine that we’ll all have our own glasses and bring them along. That would cut the expenses to the theater, to be sure. But remember, different 3-D systems require different kinds of glasses. Are audiences willing to collect one of each and keep track of which they need to take along when they head for the theater—especially those $50 ones? (“Check the theaters listings, honey. Is it RealD or Dolby tonight?”) And there are more competitors entering the market, with their own glasses.

Is current audience enthusiasm permanent?

As usual, the studios take box-office figures to equal enthusiasm on the part of fans. In public, at least, they don’t speculate as to whether 3-D might again be, as it was in the 1950s, a mere fad or a specialized taste. But because spectators are willing to pay extra now because 3-D is still a novelty, does that mean they’ll maintain that attitude once 3-D is common?

Maybe not. And maybe even now not all filmgoers care. Some even dislike 3-D.

One vocal critic is Roger Ebert. His “D-Minus for 3-D” blog entry is an eloquent takedown of the technique on aesthetic grounds. He just doesn’t like watching movies in 3-D:

One vocal critic is Roger Ebert. His “D-Minus for 3-D” blog entry is an eloquent takedown of the technique on aesthetic grounds. He just doesn’t like watching movies in 3-D:

In my review of the 3-D “Journey to the Center of the Earth,” I wrote that I wished I had seen it in 2-D: “Since there’s that part of me with a certain weakness for movies like this, it’s possible I would have liked it more. It would have looked brighter and clearer, and the photography wouldn’t have been cluttered up with all the leaping and gnashing of teeth.” “Journey” will be released on 2-D on DVD, and I am actually planning to watch it that way, to see the movie inside the distracting technique. I expect to feel considerably more affection for it.

Ask yourself this question: Have you ever watched a 2-D movie and wished it were in 3-D? Remember that boulder rolling behind Indiana Jones in “Raiders of the Lost Ark?” Better in 3-D? No, it would have been worse. Would have been a tragedy.

He refutes the widespread argument in favor of realism:

There is a mistaken belief that 3-D is “realistic.” Not at all. In real life we perceive in three dimensions, yes, but we do not perceive parts of our vision dislodging themselves from the rest and leaping at us. Nor do such things, such as arrows, cannonballs or fists, move so slowly that we can perceive them actually in motion. If a cannonball approached that slowly, it would be rolling on the ground.

It’s true that the “coming at you!” effects in 3-D movies are disruptive. I remember the 3-D in Bwana Beowulf, excuse me, Beowulf primarily for those weapons thrusting out of the screen or the gratuitous overhead tracks past beams looking down toward the distant floor. More interesting, though, is that fact that although I saw Coraline and Up in 3-D, I remember them in 2-D. Those films didn’t throw spears at the spectator or otherwise seek to pierce that fourth wall with their props. Of course as I was watching, I noticed that the mise-en-scene had layers of depth and the figures a rounded look, but apparently my life-long movie habits filtered those aspects out as the films entered my memory. I look forward to seeing both films again on DVD, and given the fact that home-theater 3-D is still in its very early stages, I’ll probably see them flat. Fine with me.

Yes, Coraline was carefully designed with 3-D effects in mind, playing with skewed perspective to characterize the two worlds the heroine moves between. But as David showed by reproducing a frame here on our merely 2-D blog, the same motifs worked without the glasses. They’re quite similar, in fact, to the forced or distorted perspective used in German films of the 1920s.

We saw District 9 this week. No 3-D, and I for one am glad about that.

On August 26, TheOneRing.net, the premiere Tolkien site on the internet (for both novels and films), pointed to the current results of its ongoing poll. They asked, “Should the Hobbit films be in 3-D?” Many of the fans who frequent TORN do so because of the films. They have heard rumors over the years, mainly hints dropped by Peter Jackson, that The Hobbit might be made in 3-D. So what is their reaction as reflected by the poll? As of August 26, 55% say no, 13% say emphatically no (“Ugh … 3-D?”), 13% are sitting on the fence, and 13% say yes.

[Aug. 29: For some reason the poll “Should the Hobbit films be in 3-D?” has disappeared from TORN. It has been replaced by a discussion of the poll results on a discussion thread in the Message Boards.]

TORN subsequently checked with director Guillermo del Toro, who reassured them, “I can safely say that, as of this moment, there are absolutely NO conversations about doing the HOBBIT films in 3D.”

Of course, my title, “Has 3-D already failed?” was meant to be provocative. Its answer depends on how one defines success. If you’re Jeffrey Katzenberg and want every theater in the world now showing 35mm films to convert to digital 3-D, then the answer is probably yes. That goal is unlikely to be met within the next few decades, by which time the equipment now being installed will almost certainly have been replaced by something else.

Right now, the big proliferation is in tiny personal screens, iPod Touches, cell phones, portable gaming devices. Will teenagers allow themselves to look dorky by sitting with 3-D glasses staring at their phones? 3-D has the effect of making films that won’t play well on the very devices that studio heads would love to see playing their movies. So far, it is a remarkably inadaptable technology to try and force on people whose movie-playing gadgets change every few years. The big break-through, home-video 3-D, is aimed at a machine that people are supposedly abandoning in favor of other screens. 3-D movies on your computer? So much for inviting pals over for a sociable evening of popcorn and a movie in your impressive home theater.

Maybe Hollywood will forge ahead, despite all the obstacles I’ve mentioned. But it also seems possible that the powers that be will decide that 3-D has reached a saturation point, or nearly so. 3-D films are now a regular but very minority product in Hollywood. They justify their existence by bringing in more at the box-office than do 2-D versions of the same films. Maybe the films that wouldn’t really benefit from 3-D, like Julie & Julia, will continue to be made in 2-D. 3-D is an add-on to a digital projector, so theaters can remove it to show 2-D films. Or a multiplex might reserve two or three of its theaters for 3-D and use the rest for traditional screenings.

If that more modest goal is the one many Hollywood studios are aiming at, then no, 3-D hasn’t failed. But as for 3-D being the one technology that will “save” the movies from competition from games, iTunes, and TV, I remain skeptical. Given the banner year that Hollywood is having, I echo Daffy Duck in The Scarlet Pumpernickel when after his lover picks him up and, crying “Save me,” races from her forced marriage, he says,“So what’s to save?”

[September 17: On the occasion of the 3D Entertainment Summit, Variety has posted an article on the subject. It deals mainly with the losses of revenue from the fact that there are too many 3-D films jostling for too few equipped screens, saying that the format “is in danger of becoming a victim of its own success.”]

Now leaving from platform 1

From a Facebook post by Tahereh

To all my friends:

What can I reply to Hossein? He’s pursuing me so avidly, but you know he isnt really a prime catch. No education, no house. If it werent for the earthquake, I wouldnt give him a second look. But he does interest me a little—he’s made me lose track of my lines so many times!

Oh no, now he’s chasing me across the field. What can I tell him? BRB!

DB here:

Many people in the film industry hold media studies in disdain, and often the feeling is mutual. Filmmakers recoil from the abstrusities of Big Theory, and academics often consider filmmakers gearheads (just before wagging their fingers and warning us about the Intentional Fallacy). But scholars like Rick Altman, John Caldwell, Janet Staiger, Kristin, and me, and younger folks like Patrick Keating and Ben Wright have been trying to study filmmakers’ creative choices in concrete ways. Some of us even ask filmmakers what they were trying to do.

So it’s heartening to see movement in the other direction. For quite a while academically trained filmmakers like James Schamus and Todd Haynes have brought ideas from their university studies into their films. Recently Reid Rosefelt composed an enlightening blog entry on Kathryn Bigelow’s intellectual side. Now some terms and ideas are being spread even more widely across the industry.

For example, in a recent Entertainment Weekly story about why women viewers like horror, we read:

One of the most consistent tropes of the genre is the character whom filmmakers call ”the final girl” — the survivor.

Actually, it was Carol Clover, scholar of horror movies and Scandinavian epics, who came up with the “final girl” nickname in her book Men, Women, and Chainsaws. Going back to the EW sentence, you notice that academics helped popularize the term genre too, which you seldom find in Hollywood’s patter before the 1970s. And the very word trope smells of classrooms and chalkdust.

Even more striking is a recent Variety article entitled, “Transmedia Storytelling Is Future of Biz.” Peter Caranicas explains that it involves “developing a piece of intellectual property across multiple media platforms.” The Star Wars franchise is the major modern instance, as Caranicas explains.

What Lucas did went several steps beyond old-style character licensing and brand extensions. He created a unified body of work with an extensive backstory and mythology, and he determinedly guarded its canon [another academic term—DB] while simultaneously opening up peripheral parts of his universe to exploration by other contributors.

One of my former students assures me that Kristin and I used the term “transmedia” back in the 1990s, but we have no memory of doing so. More relevantly, Liz Rosenthal reminds us that Peter Greenaway was pushing the concept in 1993. “If the cinema intends to survive, it has to make a pact and a relationship with concepts of interactivity and it has to see itself as only part of a multimedia cultural adventure.”

In any case, the person who brought the concept of transmedia storytelling to the forefront of media studies, and thus industry parlance, was another Wisconsin student, Henry Jenkins. Henry has made the concept part of his broader research into how modern media connect with audiences, particularly fan audiences. In his 1992 essay on Twin Peaks, he was already exploring how fans used the still-emerging internet to respond to a range of ancillary texts around Lynch’s TV series. You can get a quick acquaintance with his most recent ideas in this 2007 blog essay. For me, his argument emerged most vividly in a talk he gave at Madison some years ago. The lecture became the chapter “Searching for the Origami Unicorn” in his book Convergence Culture. For his more recent thinking, you can check his current course syllabus, which includes reading and web references, in the 11 August entry here.

The platform-shifting that Caranicas describes is planned and executed at the creative end, moving the story world calculatedly across media. These, dubbed by Jenkins “commercial extensions,” differ from “grassroots extensions,” which are created by audience members without the permission, or even the knowledge, of the creators. The commercial extensions are what I’ll be considering here.

From aggregator Movie MMORPG:

Welcome to a sophisticated world teetering on the edge of decadence. Get hammered on Italian cocktails. Fight your way out of a hospital jammed with nymphos. Cheat on your wife. Seduce a married man. Wander through the streets and stare at gushing water. Have you got what it takes to survive a day in LaNotteCity? You’ll get hooked, since the endgame is always inconclusive!

As it’s currently discussed, transmedia storytelling has two uncontroversial components and one rare but intriguing one.

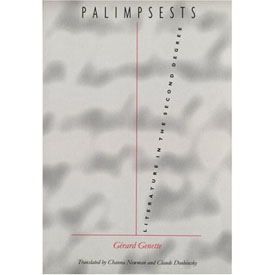

First, the term implies that a story is spread among a series of discrete “texts.” This “hypernarrative” idea was explored with taxonomic zeal by Gérard Genette in his 1982 book Palimpsests. His taxonomy of storytelling is worth considering a little here because he anticipated several possibilities we’re seeing now. Many of his categories have parallels in cinema, but I’ll stick to his domain, literature.

First, the term implies that a story is spread among a series of discrete “texts.” This “hypernarrative” idea was explored with taxonomic zeal by Gérard Genette in his 1982 book Palimpsests. His taxonomy of storytelling is worth considering a little here because he anticipated several possibilities we’re seeing now. Many of his categories have parallels in cinema, but I’ll stick to his domain, literature.

Novels and short stories feed off other novels and short stories. Obvious examples are parodies, pastiches, sequels, and continuations (sequels not written by the original author). Genette also considers what he calls the “transposition,” a very roomy category that’s of particular interest to us.

Transpositions are things like translations, rewritings, and literary adaptations, as when a novel becomes a play. A transposition also occurs when the original text is pruned or compressed, as in abridged versions of Don Quixote or Moby-Dick. At the other quantitative extreme is what Genette calls augmentation. Here, the derivative work expands the original, either in style (three sentences replace one) or narrative material (extra scenes or plots).

Yet another sort of transposition occurs when the story events in the original are rendered through alternative literary techniques. Charles Lamb retells Ulysses’ adventures in a different order than Homer does, and someone could rewrite the events of Madame Bovary in first person, from Charles’ point of view. When Genette was writing, he had to reach for some esoteric examples, but nowadays we have others. Alice Randall’s The Wind Done Gone (2001) retells Gone with the Wind from the point of view of a slave on Tara. The novel Wicked is a large-scale example, as is Tom Stoppard’s Rosenkrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead.

All these examples of hypernarrative operate within a single medium. The second condition of transmedia storytelling is, of course, that it crosses media. Genette considers drama and written literature to be all part of the same medium, but if you don’t, then novels turned into plays, like Les Miserables, would count as transfers across media.

In this sense, transmedia storytelling is very, very old. The Bible, the Homeric epics, the Bhagvad-gita, and many other classic stories have been rendered in plays and the visual arts across centuries. There are paintings portraying episodes in mythology and Shakespeare plays. More recently, film, radio, and television have created their own versions of literary or dramatic or operatic works. The whole area of what we now call adaptation is a matter of stories passed among media.

What makes this traditional idea sexy? I think it’s a third, less common component that Henry has spotlighted. Some transmedia narratives create a more complex overall experience than that provided by any text alone. This can be accomplished by spreading characters and plot twists among the different texts. If you haven’t tracked the story world on different platforms, you have an imperfect grasp of it.

I can follow Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes stories well without seeing The Seven Percent Solution or The Private Life of Sherlock Holmes. These pastiches/continuations are clearly side excursions, enjoyable or not in themselves and perhaps illuminating some aspects of the original tales. But according to Henry, we can’t appreciate the Matrix trilogy unless we understand that key story events have taken place in the videogame, the comic books, and the short films gathered in The Animatrix. The Kid in The Matrix Reloaded makes cryptic reference to finding Neo by fate, but only those who have watched the short devoted to him knows what that means. If Sherlock pastiches are parasites, the texts around The Matrix exist in symbiosis, giving as much as they take.

This strategy differentiates the new transmedia storytelling from your typical franchise. In most film franchises, the same characters play out their fixed roles in different movies, or comic books, or TV shows. You need not consume all to understand one. But Henry envisages the possibility of creating a whole that is greater than its parts, a vast narrative experience that doesn’t end when the book’s last page is turned or the theatre lights come up. His idea seems to be echoed in Will Wright’s suggestion:

It’s a fractal deployment of intellectual property. Instead of picking one format, you’re designing for one mega-platform. . . . We’ve been talking about this kind of synergy for years, but it’s finally happening.

Stimulating as this prospect is, it remains rare. The Matrix is perhaps the best example, but Henry suggests that it’s also an extreme instance: “For the casual consumer, The Matrix asked too much. For the hard-core fan, it provided too little” (p. 126). More common is a Genette-style transposition, in which the core text—usually the movie—is given offshoots and roundabouts that lead back to it. As I understand it, the Star Wars novels operate under the injunction that although they can take a story situation as the basis for a new plot, in the end that plot has to leave the films’ story arc unchanged. Similarly, websites with puzzles, games, clues, and other supplementary material tend to be subordinate to the film, planting hints and foreshadowings (The Blair Witch Project, Memento). Alternatively, the A. I. website provided a largely independent story world that impinged on the movie’s action only slightly.

The “immersive” ancillaries seem on the whole designed less to complete or complicate the film than to cement loyalty to the property, and even recruit fans to participate in marketing. It’s enhanced synergy, upgraded brand loyalty.

For the most part Hollywood is thinking pragmatically, adopting Lucas’ strategy of spinning off ancillaries in ways that respect the hardcore fans’ appreciation of the esoterica in the property. Caranicas quotes Jeff Gomez, an entrepreneur in transmedia storytelling, saying that for most of his clients “we make sure the universe of the film maintains its integrity as it’s expanded and implemented across multiple platforms.” It would seem to be a strategy of expanding and enriching fan following, and consequent purchases.

As best I can tell, then, in borrowing this academic idea, the industry is taking the radical edge off. But is that surprising?

Excerpt from www.ballsup.net

What a bloody week. Just now had a chance to update things. Fact is, it’s me last post. Luckily I let that cellphone drop and grabbed the satchel just before it fell into the Thames. Me and the crew are now packing for Bimini, ready for living large but in a rush becuz Big Chris may be looking for us. Hang on, must upload now, someone’s knocking at me d

Henry’s chapter in Convergence Culture grants that “relatively few, if any, franchises achieve the full aesthetic potential of transmedia storytelling—yet” (p. 97). Perhaps that hopeful “yet” will be fulfilled outside Hollywood? In the realm of the avant-garde, Matthew Barney has elaborated his own private mythology, dispersed among artifacts and hard-to-see films. In this he followed Joseph Beuys and Salvador Dalí. But you could argue that these artists really weren’t telling an overarching story. They were creating secular cults, full of arcana that only the pious initiates of Gallery Culture could grasp.

What about something more accessible? This month in Filmmaker magazine, Lance Weiler has suggested that indie filmmakers embrace the concept of transmedia storytelling (though he doesn’t use the term). Weiler argues that the explosion of digital technology has so transformed narrative that the filmmaker has to keep up. Instead of creating a script, with its genre formulas and three-act layout, the filmmaker should generate a bible, which plots an ensemble of characters and events that spills across film, websites, mobile communication, Twitter, gaming, and other platforms. The filmmaker designs “timelines, interaction trees, and flow charts” as well as “story bridges that provide seamless flow across devices and screens.”

Weiler doesn’t offer any specific examples apart from his Head Trauma, a horror feature accompanied by an alternate reality game that involved mobile and online access. You can watch his account of the “evolution of storytelling” here, where he and Ted Hope speculate about transmedia storytelling as offering economic help to filmmakers, reclaiming authorship from corporations, and promoting new relations with the audience.

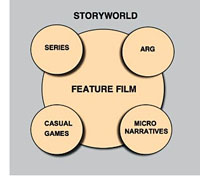

Hope and Weiler raise many fascinating questions about the prospects for multiplatform storytelling. At times, though, it seems that they accept the studio strategy of putting the film at the center of a multimedia ensemble. The diagram accompanying Weiler’s article illustrates that. It’s hard to think outside the franchise model, even if we want to denounce Hollywood for being stuck in an outdated commitment to the theatrical feature as foundational “content.”

Hope and Weiler raise many fascinating questions about the prospects for multiplatform storytelling. At times, though, it seems that they accept the studio strategy of putting the film at the center of a multimedia ensemble. The diagram accompanying Weiler’s article illustrates that. It’s hard to think outside the franchise model, even if we want to denounce Hollywood for being stuck in an outdated commitment to the theatrical feature as foundational “content.”

We should welcome experimentation, so I wish Hope, Weiler, and other creators well. But I think we ought to recognize some problems with expanding story worlds in these directions.

For one thing, most Hollywood and indie films aren’t particularly good. Perhaps it’s best to let most storyworlds molder away. Does every horror movie need a zigzag trail of web pages? Do you want a diary of Daredevil’s down time? Do you want to look at the Flickr page of the family in Little Miss Sunshine? Do you want to receive Tweets from Juno? Pursued to the max, transmedia storytelling could be as alternately dull and maddening as your own life.

Sure, somebody might go for it. Kristin points out, though, that people who would be motivated to follow up on all the transmedia bits of a spreadeagled narrative are people who would identify themselves as part of a fandom. There aren’t that many films/franchises that generate profoundly devoted fans on a large scale: The Matrix, Twilight, Harry Potter, The Lord of the Rings, Star Wars, Star Trek, maybe The Prisoner. These items are a tiny portion of the total number of films and TV series produced. It’s hard to imagine an ordinary feature, let alone an independent film, being able to motivate people to track down all these tributary narratives. There could be a lot of expensive flops if people tried to promote such things.

Consider a deeper point. Transmedia storytelling in the radical sense is posited as an active, participatory experience. Henry suggests that fans will race home from the multiplex to study up on iconography in The Matrix. Weiler’s article is accompanied by a hierarchy that lists “layers of interactivity.” The most superficial is “Passive Viewing,” defined as “Sit back and watch.” (Here Weiler parts company with Henry, who doesn’t consider ordinary viewing passive.) Further along are layers involving social networking, playing games, discussing or interacting with characters, finding hidden content, and even creating elements of the story world.

But it seems to me that film viewing is already an active, participatory experience. It requires attention, a degree of concentration, memory, anticipation, and a host of story-understanding skills. Even the simplest story gears up our minds. We may not notice this happening because our skills are so well-practiced; but skills they are. More complicated stories demand that we play a sort of mental game with the film. Trying to guess Hitchcock or Buñuel’s next twist can engross you deeply. And the very genre of puzzle films trades on brain strain, demanding that the film be watched many times (buy the DVD) for its narrational stratagems to be exposed. Films are interactive in the way a board game is: each move blocks certain possibilities, another anticipates what you’re going to do (mentally).

Moreover, how the ancillary texts add to the film is a crucial matter. No narrative is absolutely complete; the whole of any tale is never told. At the least, some intervals of time go missing, characters drift in and out of our ken, and things happen offscreen. Henry Jenkins suggests that gaps in the core text can be filled by the ancillary texts generated by fan fiction or the creators. But many films thrive by virtue of their gaps. In Psycho, just when did Marion decide to steal the bank’s money? There are the open endings, which leave the story action suspended. There are the uncertainties about motivation. In Anatomy of a Murder, did Lieutenant Manion kill his wife’s rapist in cold blood? Likewise, being locked to a certain character’s range of knowledge is the source of powerful emotional effects. We want to make the discoveries along with the character, be he Philip Marlowe or Travis Bickle.

The human imagination abhors a vacuum, I suppose, but many art works exploit that impulse by letting us play with alternative hypotheses about causes and outcomes. We don’t need the creators to close those hypotheses down. Indeed, you can argue that one of the contributions of independent film has been the possibility of pushing the audience toward accepting plots that don’t fit clear-cut norms. That innovation shrinks if we can run home to get background material online. By following the franchise logic, indie films risk giving up mystery.

At this point someone usually says that interactive storytelling allows the filmmaker to surrender some control to the viewer, who is empowered to choose her own adventure. This notion is worth a long blog entry in itself, so I’ll simply assert without proof: Storytelling is crucially all about control. It sometimes obliges the viewer to take adventures she could not imagine. Storytelling is artistic tyranny, and not always benevolent.

Another drawback to shifting a story among platforms: art works gain strength by having firm boundaries. A movie’s opening deserves to be treated as a distinct portal, a privileged point of access, a punctual moment at which we can take a breath and plunge into the story world. Likewise, the closing ought to be palpable, even if it’s a diminuendo or an unresolved chord. The special thrill of beginning and ending can be vitiated if we come to see the first shots as just continuations of the webisode, and closing images as something to be stitched to more stuff unfolding online. There’s a reason that pictures have frames.

Another drawback to shifting a story among platforms: art works gain strength by having firm boundaries. A movie’s opening deserves to be treated as a distinct portal, a privileged point of access, a punctual moment at which we can take a breath and plunge into the story world. Likewise, the closing ought to be palpable, even if it’s a diminuendo or an unresolved chord. The special thrill of beginning and ending can be vitiated if we come to see the first shots as just continuations of the webisode, and closing images as something to be stitched to more stuff unfolding online. There’s a reason that pictures have frames.

In between opening and closing, the order in which we get story information is crucial to our experience of the story world. Suspense, curiosity, surprise, and concern for characters—all are created by the sequencing of story action programmed into the movie. It’s significant, I think, that proponents of hardcore multiplatform storytelling don’t tend to describe the ups and downs of that experience across the narrative. The meanderings of multimedia browsing can’t be described with the confidence we can ascribe to a film’s developing organization. Facing multiple points of access, no two consumers are likely to encounter story information in the same order. If I start a novel at chapter one, and you start it at chapter ten, we simply haven’t experienced the art work the same way. This isn’t to say, of course, that each of us has an identical experience of a movie. It’s just that our individual experiences of the film overlap to an extent that allows us to talk about the patterning of the story under our eyes.

In correspondence with me, Henry suggests that transmedia storytelling may work best with television because of the serialized format; different people hop aboard at different points. I’d add that television’s installment-based storytelling, operating in the lived time of the audience, allows time for viewers to explore or create media offshoots. The installment-based nature of serial TV poses intriguing aesthetic problems of continuity, coherence, and memory. (See Jason Mittell’s essay on this matter.) For films, however, which are typically designed to be consumed in one sitting, multiple points of entry will tend to make plot patterns less clearly profiled.

If transmedia storytelling is difficult to apprehend for the viewer, it also makes critical analysis and evaluation much more difficult. How might we analyze overarching patterns of multiplatform plotting in The Matrix? True, one can itemize the inputs and decipher the citations, but it’s very hard to show how they work together, how they unfold, what it all adds up to—except to note that different people will encounter information bits at different times and with different states of knowledge.

Gap-filling isn’t the only rationale for spreading the story across platforms, of course. Parallel worlds can be built, secondary characters can be promoted, the story can be presented through a minor character’s eyes. If these ancillary stories become not parasitic but symbiotic, we expect them to engage us on their own terms, and this requires creativity of an extraordinarily high order.

Henry Jenkins suggests that for big-budget projects, this means finding unusually gifted collaborators. In the indie sector, the obstacles are even more considerable. Whether the result is Wendy and Lucy or Goodbye Solo, creating a first-rate feature-length movie takes tremendous talent, sweat, and resourcefulness. It is immensely harder to create a story universe that sustains the same intensity and quality across platforms. True, you can sprinkle clues and cryptic references among websites and YouTube shorts. The formulas of genre (horror, mystery) help you generate shock effects and mystification in teaser trailers. Appeal to stock characterization helps you mount a “realistic” Second Life life. But building a vast, sturdy world teeming with distinctive characters, unpredictable plotting, and human resonance is an immense task.

We await our multimedia Balzac. In the meantime, maybe indie filmmakers should settle for trying to be Chekhov.

http://tinyurl.com/scarkiller

Debbie, sorry 2 hav left SOOOO suddenlike. am @ Gila flats = cactus + varmnts. LOL with Blankethead!!! :-/

Uncl Ethan

Thanks to Henry Jenkins for comments on this entry. He recommends that interested readers have a look at Geoffrey Long’s 2007 MA thesis on the Jim Henson company, available, along with many other MIT projects, here. Thanks also to Kristin and Jeff Smith for suggestions, and to Janet Staiger for correcting my memory and calling attention to Dennis Bound’s book on “transmedia poetics” as applied to Perry Mason.

PS 11 Sept: Henry Jenkins has responded to my entry, with the first of three installments starting here.