French fortuities

Wednesday | January 13, 2010 open printable version

open printable version

DB here:

What is it about French doors and French books? I have no trouble opening a door in other countries, but here it’s hard to tell whether to push or pull. Yes, I know a door swings toward its hinged side, but sometimes the hinges seem hidden. Yes, there are often instructions on the door (POUSSEZ, TIREZ), but often there aren’t. And it’s not just me. French people ahead of me in a queue seem just as baffled. Yesterday, a kind lady helping me at the Bibliothèque Nationale made a mistake when opening her own office door. I also note that some doors have handwritten instructions (POUSSEZ, TIREZ) taped awkwardly to the glass. I’ve even seen one sporting a tired Post-It.

As for books, over the years I’ve fretted over a lack of coordination on two matters. First, in what direction will you print the book title on the spine? The French do it either way, top to bottom or bottom to top. Second, where does the table of contents go? Usually at the back, but not always.

Don’t get me wrong; this isn’t an anti-French diatribe. I’ve loved Paris since my first trip here in 1970. Some people come here to eat, to wander through a glorious city, to visit museums. I do some of those things too, but mostly I’ve come over the years to do research, explore bookshops, and to watch movies. It makes me boring company, I know—I don’t sit much in cafes reading newspapers and watching passersby—but it makes me happy. And Paris is about nothing if not happiness.

My first two lectures at the École Normale Supérieure seem to have gone reasonably well; I’ve got one more to give next Monday. At other times, while Kristin does Egyptological research in Berlin, I’ve done what I usually do in this city.

Landscapes and portraits

Eugene, or Eugène, Green is one of the most rigorously—some might say rigidly—formalist of contemporary filmmakers, and his moves are on display in La Réligieuse portugaise (The Portuguese Nun, 2009). It’s another movie about the making of a movie. Julie, a young Parisian with Portuguese roots, comes to Lisbon to shoot a film based on a seventeenth-century epistolary novel. Although the plot involves the passionate romance between a military officer and a nun, the project will apparently consist mostly of Julie’s voice-over and include only a couple of scenes showing her with the officer.

Green’s film exemplifies that process Dwight Macdonald described in Antonioni: the Talkies become the Walkies. Julie drifts around the city, meeting a little boy, a man contemplating suicide, and a nun. She returns at intervals to terraces that afford her a view of the gleaming city on the bay. Through a mysterious process, she comes to change her life and perhaps get a glimpse of what is holy about ordinary existence.

The first Green film I saw was Le Monde vivant (2003) and it’s still my favorite: a fable about medieval gallantry played out in a contemporary landscape, with knights and ladies and monsters wearing today’s casual clothes. I also like Le Pont des Arts (2004), though its resolute dedication to the values of High Art can put populists off.

Filming handsome women and beautiful men, Green subjects them to a regimen of geometrical framing and cutting. La Réligieuse portugaise opens with what seem to be standard establishing shots, but soon we realize that they present symmetrical pans across city views, and the shots are themselves embedded in an ABAB editing pattern. The opening not only sets up the location but announces, at one remove, the visual style.

Most noticeable is Green’s minimalist formula for a conversation. After seeing the actors in a full shot, often in profile, we get over-the-shoulder views. No surprise there, or in the tight ¾ singles that follow. But then we get straight-on facial close-ups, far more strictly patterned than comparable passages in, say, Demme’s Manchurian Candidate. Moreover, each line of dialogue is delivered whole in each shot; I didn’t detect any sound overlap at a cut. Each character is locked into his or her own image-sound module, and the scene strings these together.

The film’s trailer barely hints at the story but announces the modularity of Green dialogue. Like the opening, it introduces us to the visual scheme rather than the dramatic nexus.

Eventually you get used to these to-camera exchanges (the climactic one between Julie and the nun seems to last nearly a reel). So Green varies the format by supplying some other angles and even moments when characters turn from a scene to look enigmatically out at us—a sort of logical extension of the to-camera device. This could be a suffocating style, but I think that the prolonged landscape views give the movie a chance to breathe in a different rhythm. And Green has a certain humor about his cookie-cutter technique. He plays the director of the film, and his camera positions in that project never seem to replicate those in the movie we’re watching. Still, his crew is usually shot staring straight out at us.

The hieratic style seems to fit a movie which is, like Green’s others, about mysterious and even mystical forces inhabiting our world. Maybe the visual approach is too simple, and the plot’s quasi-resolution borders on the simplistic, but I’ve always liked films that apply strict structures to ordinary dramatic material in the hopes that something evocative will flash out. Ozu of course does this best, and in ways that Green may have picked up on; he’s usually compared to Bresson and Oliveira, but his dialogue patterns seem to owe a lot to the Japanese master. La Réligieuse portuguese is a little precious and unashamedly pretentious, but those qualities didn’t stop me from enjoying it.

Agora-phobia, apocalyptic visions, and dotty murders

I’d have welcomed a little Greenian simplicity and rigor in Agora, Alejandro Amenabar’s secular-humanist sword-and-sandal account of political and religious struggles in Alexandria in the early Christian era. It boasts the standard stuff: wailing pseudo-World-Music score, now-you-see-it-now-you-don’t cutting, glimpses of physiognomically challenged bystanders gaping at their betters, brawny heroes fighting for both Big Ideas and the love of a woman, swooping helicopterish CGI views of landscapes, handheld scenes of mass carnage, and overexplicit performances. Rachel Weisz reads her dialogue Special Delivery, often supplying two or three facial expressions per line.

She plays Hypatia, a philosopher-teacher who, in the movie’s version, anticipates the discovery of planetary orbits by a few hundred years. I’m all for a story centered on a smart scientist who happens to be a woman, and it’s a provocative dig at today’s fundamentalists to reverse costume-picture conventions and make early Christians the dogmatic oppressors. But Hypatia’s quest is literalized in a graphic motif that nobody can miss, and it’s embedded in a commonplace romantic tale of spurned lovers who don’t share her commitment to higher things, like the mathematics of conic sections. She is a political idealist surrounded by political opportunists, and the result can only be martyrdom. There are good middlebrow costume pictures, but Agora isn’t one of them.

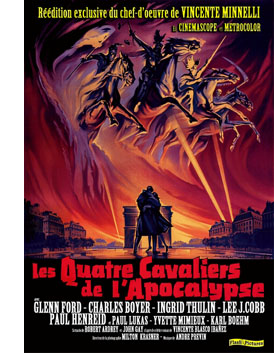

You want ersatz history done right, go to Hollywood. Minnelli’s 4 Horsemen of the Apocalypse (1962) updates the old Metro property from World War I to the Big War. I saw it on 16mm long ago, before I came to appreciate Minnelli, and didn’t want to give it a go on DVD, so I was happy to see a newish copy in 35mm at the Filmothèque in the Latin Quarter. The theatre was minuscule, and the lobby was crammed with viewers anxious to escape the cold (see above). But both the Red and the Blue screening rooms were cozy, and a front-row seat afforded me a perfect view.

You want ersatz history done right, go to Hollywood. Minnelli’s 4 Horsemen of the Apocalypse (1962) updates the old Metro property from World War I to the Big War. I saw it on 16mm long ago, before I came to appreciate Minnelli, and didn’t want to give it a go on DVD, so I was happy to see a newish copy in 35mm at the Filmothèque in the Latin Quarter. The theatre was minuscule, and the lobby was crammed with viewers anxious to escape the cold (see above). But both the Red and the Blue screening rooms were cozy, and a front-row seat afforded me a perfect view.

I found the first half-hour or so of 4 Horsemen to be freighted with fairly clunky exposition laying out family relations. The high point is Lee J. Cobbs’ characteristically scenery-gobbling performance as the patriarch, culminating in his crazed vision of the night riders in the sky during a thunderstorm. Once the plot moves to Paris and Julio (Glenn Ford) falls in love with Marguerite (a weakly dubbed Ingrid Thulin), the drama gets going. Julio starts as an It’s-not-my-fight hero who, unable to flee with the married woman he loves and sickened by the depredations of the Gestapo, becomes a Resistance conspirator.

In general, I thought that the old actors—Paul Heinreid, Paul Lukas, and Charles Boyer—gave the movie most of its body and pathos. In particular, Lukas and Boyer evoke each man’s sorrow at choosing the wrong path in history, both personal and political. 4 Horsemen, made when old Hollywood was in its death throes, still had a sheen that films would lose in a few years. The scenes in the Paris Métro are shot quite close with Panavision lenses, which enables Minnelli to avoid big establishing shots and create tight, clever alignments of Julio on the platform with his woman Resistance courier. These sequences have a concise precision that American cinema would soon lose. Granted, narrative point of view skips around awkwardly, perhaps because of cutting in post-production. We probably need more of the daughter , although that would have the unfortunate consequence of giving us more of Yvette Mimieux. Nonetheless, Amenabar could study how to present motifs by noting the casual way cigarettes and lighters thread through the plot.

4 Horsemen goes rewardingly wacko at certain points, particularly in the red-soaked montages that stretch 1940s stock footage to CinemaScope proportions. (Truffaut fiddled with the same distortions, more expressively, in Jules et Jim, released at almost exactly the same time). Unhappily, these sequences are nothing like as delirious as the climactic stretch of Some Came Running. In sum, for me, mid-range Minnelli; but that’s pretty good. If Tarantino didn’t watch this in preparation for Inglourious Basterds, he should have.

Cited in that same Tarantino movie is an Occupation classic I’d never seen: Clouzot’s first feature, L’Assassin habite au 21. Of course it was playing, thanks to the attention focused on Clouzot’s unfinished L’Enfer project. L’Assassin‘s opening sequence is a flamboyant piece of work, and it includes what might be the first appearance of that strange tracking shot we start to see in 1970s horror films. You know the shot, in which the framing oscillates between objective and subjective views, now exploring, now stalking. After this flashy start, L’Assassin devolves into black comedy, putting on display a gallery of murder suspects, all eccentrics and grotesques living in the same pension. (In a metacinematic jab, it’s the “Pension des Mimosas,” citing one of the most celebrated French films of the 1930s.) Not as sour and cynical as Le Corbeau, the movie has a mordant charm, which extends to the sneakily misleading title.

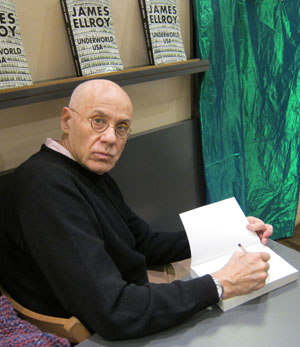

Finally, two lucky encounters. Between Four Horsemen and L’Assassin, I had a couple of hours so I slipped into a bookshop. Who should be there but James Ellroy, signing the French translation of Blood’s a Rover? Since I’m a fan, especially of the L.A. Quartet, I had to get an autographed copy. We chatted a little about his sentences, about his mother’s Wisconsin origins, and about filmmaker Ben Meade, some of whose work (Das Bus, Bazaar Bizarre) has involved Ellroy. While Ellroy signed books, he sang, “C’est si bon.”

Another encounter, this one a bit of a stretch. Tuesday I went to the Bibliothèque to reserve some scenarios of Louis Feuillade films. Wandering in the neighborhood, I came upon a tiny, appropriately named street. Not my guy, though they may have been related; this La Feuillade was a military officer of apparently mixed accomplishments. But I’ll take whatever fortuities I can get.