Archive for March 2010

Foreground, background, playground

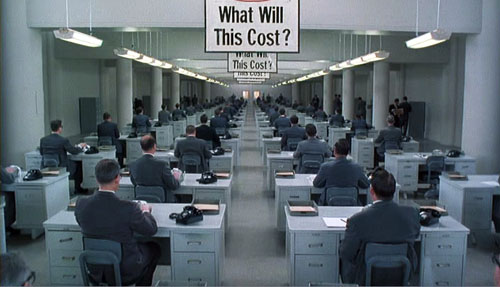

The Devil and Miss Jones (1941); The Hudsucker Proxy (1994)

DB here:

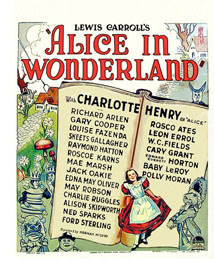

I’ve been waiting for thirty years for Alice in Wonderland. No, not the theatrical release of Tim Burton’s version. That interests me only mildly. I’m referring to the DVD release of the 1933 Paramount picture. I saw it on TV as a kid, and remembered it only dimly. But it bobbed up on my horizon in the summer of 1981 when I was doing research on our book The Classical Hollywood Cinema.

I was in the old Academy library in Los Angeles studying the emergence of certain compositional schemas. I can’t recall what put me on the track, but I requested the shooting script of Alice. What came was Farciot Edouart’s copy, over six hundred pages teeming with sketches for each shot. And a lot of those shots had a startling similarity to good old Citizen Kane.

I was in the old Academy library in Los Angeles studying the emergence of certain compositional schemas. I can’t recall what put me on the track, but I requested the shooting script of Alice. What came was Farciot Edouart’s copy, over six hundred pages teeming with sketches for each shot. And a lot of those shots had a startling similarity to good old Citizen Kane.

I was reluctant to attribute pioneering spirit to director Norman Z. McLeod. Instead, I realized that these images’ somewhat freaky look owed more to one of the strangest talents in Hollywood history.

I tried to see Alice in Wonderland, but I couldn’t track down a print. So for years I’ve been waiting to find if it confirmed what I saw on those typescript pages. In the meantime, for the CHC book and thereafter, I’ve bided my time, sporadically looking in on the career of one of Hollywood’s most eccentric creators. He’s the subject of a new web essay I’ve just posted here (or click on the top item under “Essays” on the left sidebar). Today’s blog entry is a teaser trailer for that.

Deep thinkers

It’s commonplace now to say that Citizen Kane (1941) pioneered vigorous depth imagery, both through staging and cinematography. Many of the film’s shots set a big head or object in the foreground against a dramatically important element in the distance, both kept in fairly good focus. But where did this image schema come from?

The standard answer used to be: The genius of Gregg Toland and Orson Welles. In the 1980s, however, I wanted to explore the possibility that something like the deep-focus look had been a minor option on the Hollywood menu for some time. Once you look, it’s not hard to find Kane-ish images in 1920s studio films, from Greed (1924) to A Woman of Affairs (1929).

During the 1930s, William Wyler cultivated such imagery in some films shot with Toland, such as Dead End (1937), and some films shot by other DPs, such as Jezebel (1938). In turn, Toland had undertaken comparable depth experiments in films with other directors. Moreover, yet other directors, notably John Ford, had used this sort of imagery in films shot by Toland and others, such as George Barnes, Toland’s mentor. There are plenty of non-auteur instances too. (See my post on 1933 Columbia films.) We also find similar imagery in films from outside America. Here’s a stunner from Eisenstein’s Bezhin Meadow (banned 1937).

You see how complicated it gets.

What I concluded in Chapter 27 of CHC was that Toland and Welles didn’t invent the depth technique. They fine-tuned it and popularized it. Their predecessors, in the US and elsewhere, had staged the action in aggressive depth and used many of the same compositional layouts. But the wide-angle lenses then in use couldn’t always maintain crisp focus in both planes (below, American Madness, 1932).

Welles and Toland found ways to keep both close and far-off planes in sharp focus. They deployed arc lamps, coated lenses, and faster film stock. Although it wasn’t publicized at the time, we now know that some of the most famous “deep-focus” shots were also accomplished through back-projection, matte work, double exposure, and other special effects, not through straight photography. Again, though, this tactic was anticipated in earlier films. One of my favorite examples comes from a matte shot in Mr. Moto’s Gamble (1935).

Menzies seems to have planned for similar fakery. In the script for Alice in Wonderland we find: “CLOSE UP, leg of mutton. The room and characters in the background are on a transparency.”

The flashy depth compositions of the 1920s and 1930s were typically one-off effects, used to heighten a particular moment. Welles and Toland pushed further by making the depth look central to Kane’s overall design and by featuring such imagery in fixed long takes. The prominence of Kane may have encouraged several 1940s filmmakers, such as Anthony Mann, to make the depth schema part of their repertoire. But as the style was diffused across the industry, the hard-edged foregrounds became absorbed into dominant patterns of cutting and spatial breakdown. The static long takes of Kane remained a rare option, perhaps because they dwelt on their own virtuosity.

Digging up films made around the time of Kane, I found many filmmakers experimenting with the look that Toland and Welles highlighted. You can see touches of it in The Maltese Falcon (1941) and All That Money Can Buy (1941). Above all, there are two remarkable movies directed by, of all people, Sam Wood. Our Town (1940) turns Wilder’s play (itself surprisingly melancholy) into a Caligariesque exercise.

Several shots anticipate the low-slung depth, bulging foregrounds and all, that became the hallmark of Citizen Kane a year later.

Our Town also uses postproduction techniques that yield depth-of-field effects you couldn’t get in camera.

Perhaps even more startling is Wood’s Kings Row (1942), with deep-focus imagery that occasionally rivals Kane‘s.

From the evidence I was encountering, it seemed that Welles and Toland’s accomplishment was to synthesize and push further some deep-space schemas that were already circulating in ambitious Hollywood circles. Connecting some dots, I realized that one of the earliest champions of aggressive imagery in general, not just big foregrounds and deep backgrounds, was William Cameron Menzies.

Menzies frenzies

Menzies started out as an art director, most famously for United Artists. He designed sets for Mary Pickford’s Rosita (1923, directed by Lubitsch) and several Fairbanks films, notably The Thief of Bagdad (1924). He won the first Academy Award for set design and went on to a noteworthy career—most famously as production designer for Gone with the Wind (1939). He also directed films, such as Things to Come (1936) and Invaders from Mars (1953). Most significant for my purposes, he was production designer for Our Town, Kings Row, and three other films of the early 1940s directed by Sam Wood. And he designed the 1933 Alice in Wonderland. The drawings I saw in Edouart’s script were by Menzies or his assistants.

Menzies was one of the chief importers of German Expressionist visuals to the US. Although his early efforts leaned toward Art Nouveau effects, by the end of the 1920s he was cultivating a dark, contorted look keyed to the harsh geometry of city landscapes.

Since the late 1920s, Menzies had explored the possibility of steep depth compositions. He didn’t usually employ a big foreground, but he did favor overwhelming perspective–either abnormally centered or abnormally decentered. Here is his sketch for Roland West’s Alibi (1929) and the shot from the finished film.

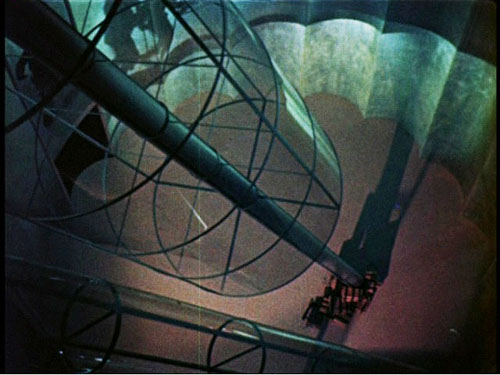

Menzies loved slashing diagonals created by architectural edges and worm’s-eye viewpoints. The harrowing opening of Things to Come is full of such flashy imagery.

Menzies calmed his style down for GWTW, although the sequences he directed bear traces of his inclinations. And in his work for other directors he managed to slip in a few odd shots. Here, for instance, is a typically maniacal central perspective view from H. C. Potter’s Mr. Lucky (1943). Squint at this image and you’ll see that it’s weirdly symmetrical across both horizontal and vertical axes.

When he met Sam Wood, it seems, Menzies found a director ready to let his imagination roam further. In these collaborations, we get depth shots à la Welles and Toland, but also skewed perspectives. Pride of the Yankees (1943/44) searches for ways to make a baseball stadium look like a Lissitzky abstraction.

Menzies subjects the partisans of For Whom the Bell Tolls (1944) to his sharp diagonals as well.

Alice, we hardly knew ye

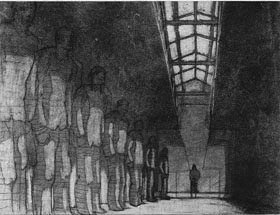

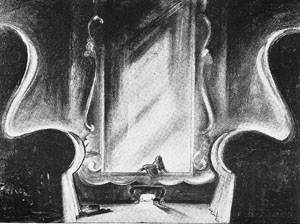

What then of Alice in Wonderland? Back in the early 1980s, I wasn’t permitted to photocopy or photograph script pages. Here is one of the few sketches I later found for the film. Alice crawls into the mirror with looming armchairs in the foreground.

Surely, I thought, the film would be an early example of the depth aesthetic that would be developed by Welles, Wyler, and Wood/ Menzies. Alas, the film has nothing like those imperious armchairs.

In fact, Alice proves a huge disappointment on the pictorial front. Menzies expended all his ingenuity on the special effects, coordinated by Paramount master Farciot Edouart. Although the spfx are not in the league of that other big 1933 effects-film King Kong, they are pretty solid for the time. It’s just that this remains a painfully arch, flatly filmed exercise.

But I look on the bright side. Menzies created some memorable movies, both on his own and with other directors. (Of his directed films, not only Things to Come but Address Unknown, 1944, remain of interest today.) Perhaps most important, his stylistic boldness may have encouraged other filmmakers to try something fresh. Most immediately there is Since You Went Away (1944), a big Selznick production that bears traces of the Menzies touch.

More broadly, Menzies represents a strand in American cinema that never really disappeared. His frantic Piranesian perspectives, canting the camera and filling the frame with grids, whorls, and cylinders, are still in use. And his head-on, wide-angle grotesquerie looks ahead to the Coen brothers. This shot of a department-store manager in The Devil and Miss Jones (1941) could come from any of their films.

Menzies’ films, though mostly not celebrated as classics, gave American cinema the permission to be peculiar. Meet me in the sidebar for a closer look at one of Hollywood’s most eccentric creators. Special thanks to Meg Hamel for going beyond the call of duty in posting that essay.

Invaders from Mars (1953); Shutter Island (2010).

Hopscotching through history

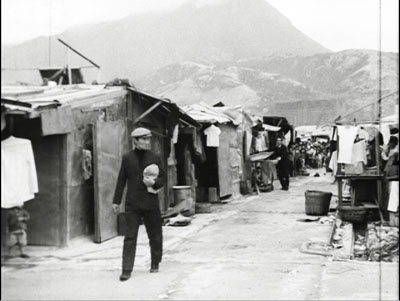

Temple Street, Hong Kong.

DB here:

Thanks to the Film Festival and screenings at the Film Archive, I’ve skipped gratefully through nearly a hundred years of local film history.

The Roast Duck legend, cooked at last?

First things, or rather first films, first. Last year local authorities declared 2009 to be the centenary of Hong Kong cinema. The long-standing claim (repeated in my Planet Hong Kong) was that To Steal a Roast Duck, aka The Trip of the Roast Duck, was made in 1909 and was the first locally produced fiction film. The controversy arose because the claim was based on later recollections of filmmakers. No fiction films from that era survived. We had no contemporary evidence that the Roast Duck was made in that year or that it was the first anything. Perhaps it wasn’t even made at all? In a blog entry last year, I summed up the arguments.

Now, thanks to the persistence of Frank Bren and Law Kar, we can come to more reliable conclusions. At a conference in December, scholars from around the world gathered at the Hong Kong Film Archive to discuss early Chinese cinema. One of the results was further revelations about the territory’s first film.

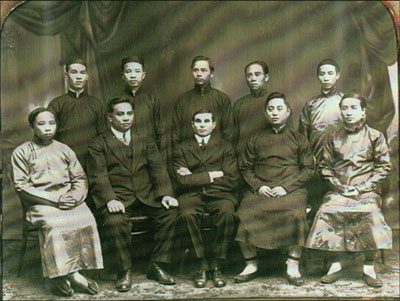

We know that at some point the Ukrainian-American entrepreneur Benjamin Brodsky came to Hong Kong and set up a film unit. (The picture above shows him surrounded by nine Chinese co-directors of the company he founded in November 1914.) An earlier Brodsky company made Roast Duck, among other films. But when?

At the conference Law Kar announced the discovery of a 1914 Moving Picture World interview with Roland Van Velzer, a photographer recruited from New York by Brodsky. During his stay in what he called “that queer land” of Hong Kong, Van Velzer shot four films in 1914.

We did a first native drama, entitled “The Defamation of Choung Chow.” With my experience and guidance the picture turned out well and when shown in public proved to be a wonderful drawing card. . . . The reason of its great popularity was because it was a Chinese piece entirely. . . . We made three other subjects during my stay there. These were: “The Haunted Pot,” The Sanpan Man’s Dream” and “The Trip of the Roast Duck,” the latter a rough “chase” picture. All of these pictures had phenomenal runs at the native theaters.

According to Van Velzer, then, the first film, made and shown in 1914, was what is now known as Chuang Tzi Tests His Wife. Roast Duck was evidently the fourth film made by the team that year.

Brodsky is significant not merely because he supported talent in producing the colony’s first fictional films. He also made long documentaries about China and Japan that played in the US. He seems to have been a colorful guy. In his barnstorming circus days, he once purged a lion with castor oil. Full details are here in an article by Bren and Kar. In the meantime, we can look forward to a more plausible centenary of Hong Kong film in 2014.

Social conscience, modern stylings

The Story of a Discharged Prisoner.

Hop ahead to the 1960s. Although the local language of Hong Kong is Cantonese, movies in Mandarin rule the market, with Shaw Brothers providing gaudily colored costume pictures, musicals, romantic dramas and comedies, and of course rather violent swordplay exercises. By contrast films made by Cantonese companies under tiny budgets look threadbare. Yet a few filmmakers tried to make Cantonese cinema more vigorous and innovative, and the most influential was Patrick Lung Kong.

Lung Kong was born in 1935, and by the time he was thirty he had performed in virtually every production role, from screenwriting and producing to publicity and distribution. Well-known as an actor since 1958, he graduated to directing in1966 with Prince of Broadcasters. His second film, The Story of a Discharged Prisoner (1967) was a landmark in local cinema, expressing sympathy for an ex-convict who tries to avoid being pulled back into crime. Lung Kong goes on to make many of the socially critical films of the period: Teddy Girls (1969), Hiroshima 28 (1974), and Mitra (1976). He ceased directing in 1981 but continued to work as an actor and distributor. He now lives in New York City, but he came back for the retrospective that the Film Archive has mounted.

I had seen some Lung Kong films in earlier visits to Hong Kong, but the retrospective will allow us to assess his career as a whole. Virtually none of his films are available on DVD, and none, as far as I know, with English subtitles. Particularly important, apart from the works I’ve mentioned, are his heavily censored film about a plague striking Hong Kong, Yesterday Today Tomorrow (1970) and the bitter domestic drama Pei Shih (1972).

When he started in the industry, he says, “I ran into these acquaintances who taunted me by saying how I was trying my hand at making Cantonese chaan pin [shabby films]. That was very insulting to the film profession in general…so I promised myself to go in and change things when the opportunity arose.” For him, change meant both modernizing Cantonese film technique and tackling social problems.

Lung Kong’s cinema, all agree, has a strong moralizing bent. He focuses on social problems—juvenile delinquency, nuclear war, prostitution, the exploitation of women in marriage. The films mix sensationalism, partly as audience bait, and social criticism. The Story of a Discharged Prisoner, reimagined by Tsui Hark and John Woo as A Better Tomorrow (1986), is at once a gangster tale and a harsh comment on the poverty that drives men to crime. Lung himself, armed with calisthenic eyebrows, plays the police officer hounding the protagonist. The Prince of Broadcasters begins as a pointed critique of popular culture, where schoolgirls fasten obsessively on a playboy radio personality. The film devolves into a more traditional thwarted-lovers plot when the protagonist reforms through his (mostly) chaste relationship with a wealthy girl.

Lung Kong’s cinema, all agree, has a strong moralizing bent. He focuses on social problems—juvenile delinquency, nuclear war, prostitution, the exploitation of women in marriage. The films mix sensationalism, partly as audience bait, and social criticism. The Story of a Discharged Prisoner, reimagined by Tsui Hark and John Woo as A Better Tomorrow (1986), is at once a gangster tale and a harsh comment on the poverty that drives men to crime. Lung himself, armed with calisthenic eyebrows, plays the police officer hounding the protagonist. The Prince of Broadcasters begins as a pointed critique of popular culture, where schoolgirls fasten obsessively on a playboy radio personality. The film devolves into a more traditional thwarted-lovers plot when the protagonist reforms through his (mostly) chaste relationship with a wealthy girl.

Lung’s film style is self-consciously 1960s modern, with zooms, calculated compositions, and handheld passages. He cuts fast, avoids dissolves, and offers fairly complex traveling shots. Looking at the cheap sets and listening to the awkward sound (including snippets of classical music and The Great Escape grabbed from LPs), one becomes aware of what a Cantonese director of the day was up against. So if the technique seems at times forced, you can at least admire Lung’s attempt to give his films a contemporary gloss.

The films were of crucial importance for local culture of the 1960s and have had continuing influence on younger directors. A very informative book of essays and interviews, produced to the usual handsome standards of the Film Archive, is in Chinese but includes a disk with a digital pdf of English translations. Two of the texts can be found here.

Jean Christophe in Macau

Another hop. I know nothing about Louis Fei, except that he was the brother of Fei Mu, whom I’ll be talking about in an upcoming entry. Romance in the Boudoir (1960) recasts the core situation of Fei Mu’s masterpiece Spring in a Small Town (1948). The situation, drawn from Romain Rolland’s novel Jean Christophe, is simple: A woman in a loveless marriage is visited by her former lover. In this version, her husband is a miserly doctor who wants the lover, Qin, to help him get a hospital post. Qin’s presence in the household rekindles the old romance and the couple hover on the edge of adultery.

Romance in the Boudoir is a bold piece of work. It opens with a prologue showing husband and wife trudging through Macau, utterly distant from each other. On the soundtrack we hear a woman singing about marriage as a prison. When Qin arrives, a parallel sequence traces him from the harbor to the household as a male vocalist sings of his weariness and broken heart. These melodic soliloquies will be evoked later in the film, when Qin and Suxuan stretch out by the fireplace and start to sing as the camera circles them.

Louis Fei makes maximal use of the house set, letting the vast staircase dominate the action on both floors. Repeated setups from the top of the stairs show the bannister cutting diagonally into the frame, pointing like an arrow to the climactic moment at the front door in the distance. Over everything hovers erotic tension, lasting several minutes during one scene when the former lovers tentatively touch one another before recoiling and then drawing toward one another again. If the doctor is somewhat caricatural, the portrayals of the wife and lover show a great subtlety, and the use of props, notably a glass of milk, is nicely modulated. This film shows how comparative large budgets enabled the Mandarin-language companies to make films of a high production standard, both in script and execution.

Dragons on fire

Now jump to 2010. Dante Lam is the hot new action director on the local scene, after the success of Beast Stalker (2008) and The Sniper (2009). Actually, like most overnight successes, he’s been at it awhile. He made an admirer of me with Jiang Hu: The Triad Zone (2000), which has one of the most graceful passages of graphic cutting (involving a red umbrella) that I’ve seen in recent Hong Kong film.

He’s back with the first big action film of the season, tagged with the barely adequate English title Fire of Conscience. The action scenes are better than the plot, which is better than the eternal impassivity of Leon Lai, a pictorial cipher in nearly every role he assumes. Still, you have to reckon with a film that includes not only a thrilling car chase, a truly scary gunfight in a restaurant, and grenades tossed around pretty casually but also a pregnant woman locked in a car slowly filling with carbon monoxide. The topper comes in the very last few shots, which provide as gruesome a flashback image as I’ve seen in quite some time and justifies the key line, “Save for revenge, what else is there?”

Visually, Fire of Conscience never surpasses the bravado of the black-and-white CGI opening, during which the camera coasts through a snapshot of action and lets clues float and scatter around the frozen characters. (It’s admittedly gimmicky, but more hypnotic than the comparable Watchmen opening.) Still, it’s exciting genre fare. What hath Ben Brodsky wrought?

Photo of Brodsky and colleagues by courtesy of Mr. Ronald Borden. The interview with R. F. Van Velzer was published in Hugh Hoffman, “Film Conditions in China,” Moving Picture World (25 July 1914), 577. Thanks to Frank Bren and Law Kar for this information, and to Tony Slide for calling attention to the article. The quotation from Lung Kong is from Clarence Tsui, “Scenes of the Crime,” South China Morning Post (22 March 2010), C1.

Patrick Lung Kong, with Sam Ho of the Hong Kong Film Archive.

The spy who came in from the typhoon

Every year I buy a used paperback of John le Carré’s The Honourable Schoolboy (1977) and take it to Hong Kong with me, to be left for someone else when I pack up to leave. One year I left a copy, then returned the following year to the same hotel. The desk clerk remembered my name and ran to the back room, where last year’s copy had been carefully retained.

During my first trip in spring of 1995, I found The Honourable Schoolboy remaindered in a Silvercord bookshop that has long since vanished. Reading the novel while I encountered HK for the first time was an exhilarating experience because, of course, the story is set there. Le Carré aficionados know that it’s the second in the Quest for Karla trilogy launched by Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy and completed by Smiley’s People. In this middle installment, we see how the mole who infiltrated the highest reaches of British intelligence wrecked the spy setup in the Crown Colony. A youngish agent, Jerry Westerby, is sent there to pursue the possibility that a member of Hong Kong’s business elite might be representing Soviet interests. Eventually, since this is Hong Kong, opium and the People’s Republic push their way into the picture.

The particular enjoyment I get from this novel during my visits owes a lot to its evocation of a city in the seventies that remains recognizable today.

Star Heights was the newest and tallest apartment block in the Midlevels, built on the round, and by night jammed like a huge lighted pencil into the soft darkness of the Peak. A winding causeway led to it, but the only pavement was a line of curbstone six inches wide between the causeway and the cliff. At Star Heights, pedestrians were in bad taste.

Yet the pleasures go far beyond acute observation of local detail. Everything that makes le Carré a splendid storyteller appears at full stretch in The Honourable Schoolboy.

The novel shows how intelligence missions, no matter how carefully planned, spin out of control because of human frailties, administrative rivalries, budget cuts, and political expediency. Sound familiar in the America of today? Like its mates in the Karla trilogy, the book begins on the periphery of the action, filling in secondary characters before building patiently towards a widely-ramifying plot. Le Carré manipulates point of view in a way that few novelists can manage, giving us a sense of circles of power made up of unnamed observers commenting on things they don’t understand. Here are the opening sentences of the first three paragraphs.

Afterward, in the dusty little corners where London’s secret servants drink together, there was argument about where the Dolphin case history should really begin. One crowd, led by a blimpish fellow in charge of microphone transcription, went so far as to claim that the fitting date was some sixty years ago. . . .

To less-flowery minds, the true genesis was Haydon’s unmasking by George Smiley and Smiley’s consequent appointment as caretaker chief of the betrayed service, which occurred in the late November of 1973.

One scholarly soul, a researcher of some sort—in the jargon, a “burrower”—even insisted, in his cups, upon January 26, 1841, as the natural date, when a certain Captain Elliott of the Royal Navy took a landing party to a fog-laden rock called Hong Kong at the mouth of the Pearl River and a few days later proclaimed it a British colony.

Our unidentified chronicler has the omniscience of an urbane insider. This is institutional memory as rumor, half-baked opinion, and shreds of fact, flavored with a touch of sarcasm. At the same time, this first page is a call to adventure. You can’t miss the rumble of kettledrums and thunder in the distance. This story will unfold in a spacious, even leisurely, manner, but will be no less suspenseful for that.

A page along we read:

The debate continues wherever old comrades meet, though the name of Jerry Westerby, understandably, is seldom mentioned. Occasionally, it is true, somebody does, out of foolhardiness or sentiment or plain forgetfulness, dredge it up, and there is atmosphere for a moment; but it passes. Only the other day. . . .

The worrisome chord is struck in a single word: understandably: At this point we understand no such thing, but five hundred pages later we will. Only then will this passage, reread, deliver its full charge of pathos.

Our chronicler’s tradecraft is impeccable. Most narratives consist of taking someone from one place to another and having him or her talk to somebody else. This poses several problems: (a) creating a vivid scene of character interchange; (b) using that interchange to summon up past events with clarity; and (c) pushing the story forward by having us understand what is gleaned from the conversation. Le Carré’s masterwork in this regard is probably Smiley’s People, which is almost Jamesian in suggesting that nearly all the important action is over, and what matters is how it has changed people’s lives. But The Honourable Schoolboy solves the problem no less deftly. Today’s spy novel would be unlikely to devote twenty pages to the questioning of the slightly gaga Reverend Hibbert, served tea by his scowling daughter. Yet it is a whole short story in itself.

Like other le Carré novels of the period, The Honourable Schoolboy displays an almost Dickensian relish in human variety. Every character is a little magnified, endowed not only with memorable tags, speeches, and bits of behavior but a pervasive attitude toward life that shifts our perspective on the main action. It’s as if the stolidity and self-containment of spymaster George Smiley calls forth extravagance in the portrayal of nearly all his staff. Connie Sachs, the bubbling, arthritic Soviet expert who carries her dog with her everywhere; de Salis, the Chinese specialist who tugs his hair and writhes as he reports; Fawn, Smiley’s devoted little bodyguard, who will grin while he breaks a man’s arms—the characters have something that most of today’s novelists, committed to the mundane, fail to give us: eccentric vitality.

The characters’ colliding attitudes emerge most starkly in a situation in which le Carré rules supreme. That is the administrative meeting. No writer I know is better at tracing the ripples of jealousy, showoffishness, toadying, and side-switching set loose when rather colorless men (it is always men) sit around a table and struggle for bureaucratic power. Le Carré is especially good on American arrogance.

One of the quiet men used the work name Murphy. Murphy was so fair he was nearly albino. Taking a folder from the rosewood table, Murphy began reading from it aloud with great respect in his voice. He held each page singly between his clean fingers.

Lest it be thought from these books, and from le Carré’s outrage against the Iraq war, that he is a reflexive anti-American, it should be said that he is no less severe with the Brits. One of his most scathing nonfiction pieces is his introduction to The Philby Conspiracy, where he denounces English snobbery and complacency for facilitating the real-life counterspying that formed the basis of his trilogy. Throughout his work, le Carré asks whether decency and kindness can survive the cynicism and compromises of a life built on deceit. Whether anyone, schoolboy or not, can retain honor in the Great Game is the central question of his Hong Kong novel.

Le Carré manages to show the bureaucrats’ tabletop swordplay as at once petty, springing from vanity and professional spite, and momentous. The world, or at least some big part of it, really is at stake. By the end of The Honourable Schoolboy, Westerby is at the end of his rope and he contemplates the betrayals and innocent deaths at which he has connived. Through his bitter disillusionment, we see an apocalypse.

As he gazed through the rear window of the car, it seemed to him that the very world that he was moving through had also been abandoned. The street markets were deserted, the pavements, even the doorways. Above them the Peak loomed fruitfully, its crocodile spine daubed by a ragged moon.

It’s the Colony’s last day, he decided: Peking has made its proverbial telephone call. “Get out, party over.” The last hotel was closing; he saw the empty Rolls-Royces lying like scrap around the harbour, and the last blue-rinse round-eye matron, laden with her tax-free furs and jewellery, tottering up the gangway of the last cruise ship; the last China-watcher frantically feeding his last miscalculations into the shredder; the looted shops, the empty city waiting like a carcass for the hordes. For a moment it was all one vanishing world; here, Phnom Penh, Saigon, London—a world on loan, with the creditors standing at the door and Jerry himself, in some unfathomable way, a part of the debt that was owed.

The end of empire has seldom been evoked so chillingly, and any day now the creditors whom Jerry imagines, moving toward hypermodernization, will be calling for payment.

The first and last novels in the trilogy became BBC adaptations, and they’re watchable, largely because of Alec Guinness as Smiley. They were shot in 16mm, largely on location, and the visual drabness fits the atmosphere of the books. (See the opening of Tinker, Tailor here.) It was evidently beyond the BBC’s budget to film The Honourable Schoolboy in Hong Kong, Cambodia, and Thailand, or plausible facsimiles thereof.

The first and last novels in the trilogy became BBC adaptations, and they’re watchable, largely because of Alec Guinness as Smiley. They were shot in 16mm, largely on location, and the visual drabness fits the atmosphere of the books. (See the opening of Tinker, Tailor here.) It was evidently beyond the BBC’s budget to film The Honourable Schoolboy in Hong Kong, Cambodia, and Thailand, or plausible facsimiles thereof.

There is a BBC radio version, but I still hope for a film adaptation some day. The story can stand independently of the trilogy, and with its multiple viewpoints, sympathetic protagonist, geopolitical themes, vivid settings, and side trips to Southeast Asian theatres of war, it could in respectful hands make for a strong feature.

In the meantime, we have the book. Granting my special fondness for its locale, I still think it one of the great novels—not great “genre” novels, but just great novels—of the century just past.

Dragons on your doorstep

DB here:

Once more, Hong Kong. Still a spellbinding place, although the municipality is doing whatever it can to force pedestrians underground and surrender the streets to cars. Even a dragon has to wait for the pedestrian light. And now, thanks to the sandstorms in China, the air is thick with pollution. I have taken defensive measures. My students probably wished I’d worn one of these more often.

Yes, that is the Boy Scout logo behind me. Why? Answer here.

I’ve already seen a few films at the Hong Kong International Film Festival, but I’ll try as usual to fold my viewings into a few thematically related entries. In the meantime, amateur reportage and celebrity gawking take over. I’m surface-skimming, I grant you, but it’s quite a surface.

For some years now, the festival has meshed with Filmart, the regional film market and trade show, and the Asian Film Awards. So you need badges.

For most of this week, the big events take place at the Hong Kong Convention Centre.

The opening reception for the festival offered all the glitter you can ask for, literally, when a cascade of sparkling paper showered down on the group photo of the organizers.

Among those present: Tang Wei, star of Lust, Caution and featured alongside Jacky Cheung in Ivy Ho’s festival-opener Crossing Hennessy.

Then there was Lisa Lu, radiant as ever. She was a wonderful star in Shaws’ golden age and continues to visit the festival annually, while sustaining her acting career.

Clara Law, director of one of the opening films, Like a Dream, embraces Lisa while Nansun Shi, herself a legendary and still central Hong Kong producer, looks on.

Filmart this year teemed with mainland Chinese media firms, but the classic Hong Kong companies also put in their appearance.

It’s reassuring to see that Wong Jing, the brains behind Naked Killer and Naked Weapon, hasn’t abandoned his old ways.

New regional enterprises are emerging. Patrick Frater and Steven Cremin, old Asian hands, have created FilmBusinessAsia as a resource of news, industry analysis, and in-depth information. Based in Hong Kong, they are ably teamed with Business Development Executive Gurjeet Chima, who speaks five languages.

Anyone interested in Asian film will find their information-packed website a must.

Two more entrepreneurs are Joey Leung and Linh La of Terracotta Distribution, a London-based outfit with an already impressive library. I met them through King Wei-chu, on the right, a programmer for Montreal’s FantAsia.

Three-dimensional film and TV were all over Filmart. Take a look at a 3D setup using the Red HD camera.

What a contraption! To shoot Potemkin, Napoleon, and a host of other 1920s films, you just needed a Debrie Parvo, that model of Style Moderne design.

Still, 3D television seems more or less ready for prime time. Can you tell the difference between reality and a 3D image?

Also at the Convention Centre was the Asian Film Awards ceremony, which whizzed by in two hours. On the red carpet runway you could see some celebrities, such as Wai Ying-hung, a Shaw Brothers ingenue and kung-fu warrior from the 1980s who would win for best supporting actress in Ho Yuhang‘s At the End of Daybreak.

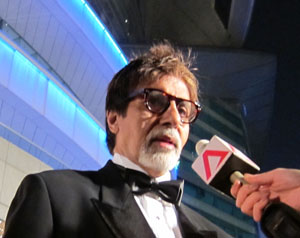

Among the slinky models and standard-issue teen idols on the red carpet, a note of dignity was struck by Amitabh Bachchan, who got a lifetime achievement award. He might as well officially change his name to Megastar Amitabh Bachchan.

For a complete rundown on the award winners, you can go here. We wrote about three of them in earlier blog entries: Bong Joon-ho‘s Mother (best picture, best actress, best screenplay), Ho Yuhang‘s At the End of Daybreak (best newcomer, best supporting actress) and Chris Chong‘s Karaoke (best editing). Among the nominees, we also wrote about Love Exposure, About Elly (I really wish it had won something), Cow, Air Doll, and Breathless. I was particularly struck by the cheers and whoops the audience gave Wang Xueqi of Bodyguards and Assassins, which I caught up with today. He’s an actor of gravity, who unlike most Hong Kong performers believes that less (hamming) is more (engrossing).

With the big launching events over, we can get down to the real business: Watching movies and discovering some sublimity in them. More entries, as usual, to come.