Archive for March 2010

From books to blogs to books

Kristin here:

This is a follow-up to David’s latest entry on the supposed death of film criticism.

![]() As academics rather than reviewers, we’ve tried to take advantage of the benefits offered by the Internet. In our pre-blogging days, David used his website to post articles. They came out faster than they would if submitted to a print journal, and they would reach a larger audience, at least in the short run. When we added a blog to the site, it became, as David wrote, “our own magazine.”

As academics rather than reviewers, we’ve tried to take advantage of the benefits offered by the Internet. In our pre-blogging days, David used his website to post articles. They came out faster than they would if submitted to a print journal, and they would reach a larger audience, at least in the short run. When we added a blog to the site, it became, as David wrote, “our own magazine.”

For a while putting a lot of entries no place but on the blog seemed fine. Our stat-counter tells us that a lot of the older entries get read. Either a teacher assigns them or someone finds an old link or discovers the blog for the first time through a new entry and then clicks around on a lot of the older pages. So it’s not as though the pieces disappear a few weeks or so after they’re written. The blog has become a large resource by now.

But what about the really long run? I tend to want to see my prose in print. It’s unlikely that the blog will completely crash, but what if it did happen? And what becomes of all the material on the blog in the distant (I hope) future when we’re not around to keep an eye on it?

Ironically, the internet has proved to be a good way of extending the life of our print books. David’s Ozu and the Poetics of Cinema went out of print, and now it’s online, improved with better pictures, many in color. My Exporting Entertainment was in print for such a short time that few knew I had written it; now it has found a home on the website. Now Planet Hong Kong is out of print as well. David plans to update it and post the new version on the website as well.

Ironically, just as we were contemplating the migration of our books from print to pixels, Rodney Powell, of the University of Chicago Press, inquired as to whether we would be interested in turning a selection of our blog entries into a book. It wouldn’t be necessary to take down the original entries, he assured us. We couldn’t have done that anyway, since our textbook Film Art has just added a feature that alerts teachers and students to relevant essays via URLs in the margins. But we agreed to such a collection, and we’ve just sent in the manuscript for copy-editing. The result, called Minding Movies, should be out next spring.

There hasn’t exactly been a stampede to collect blog entries as books, but some presses, including Chicago, are trying out this new genre. Profile Books has just published classicist Mary Beard’s It’s a Don’s Life, based on her blog of the same name. (I highly recommend her book, The Fires of Vesuvius.) Economists Gary S. Becker and Richard A. Posner’s Uncommon Sense (also the University of Chicago Press) culls items from The Becker-Posner Blog.

Apart from blog-based books, the University of Chicago Press has some more traditional books of film criticism in press. One is a collection of Dave Kehr’s reviews from his days with the Chicago Reader (1974-1986). In September it will also publish a book gathering writings by Jonathan Rosenbaum (some of which have also been posted on his website) called Goodbye Cinema, Hello Cinephilia: Film Culture in Transition. Chicago has announced a third volume of Roger Ebert’s Great Movies for October of this year. Although some of these pieces have been posted on the authors’ websites after their initial print publication, Minding Movies is unusual in that its entire contents, like those of the Becker-Posner book, were written designedly for the Internet.

Will people want books of blog material that’s available for free online? From our standpoint it seems odd. True, some people just don’t like reading anything longer than a few paragraphs on a computer screen. But choosing the entries to put into the book made us realize how big the blog has become over three and a half years. It’s not easy to just browse through.

This entry marks post number 320 on Observations on Film Art. We were able to include 31 of that total in the book, which will be around 96,000 words. The inescapable conclusion is that we have posted ten volumes’ worth of stuff on the blog. Whew!

Not that we would want to put everything on Observations on Film Art into print. There are a lot of relatively topical items like festival coverage and reports on lectures and conferences and DVD supplements. My piece on the “I Drink Your Milkshake” phenomenon brought us our single busiest day ever (over 20,000 page loads), but it dealt with a fad and certainly doesn’t deserve to go between the covers of a book. Still, quite a few of the entries do reflect research and analysis of the sort that we would ordinarily put into our articles.

Even before it ever occurred to us that we could put together a blog collection, colleagues had said, “Your stuff deserves to be published as a book.” Maybe that’s a sign of the lingering sense that print publication is still more serious than blogging. Another implication seems to be that, while pieces written to be posted online may be excellent and worthy of publication in any format, they also need to be rescued from the vastness that is the Internet. Yes, Google can help people find David’s entry on staging in There Will Be Blood in a flash. But if the reader doesn’t have any particular film or other specific topic in mind and just wants to see our best pieces, it’s not that easy.

Incidentally, “Hands (and faces) across the Table,” the There Will Be Blood piece, won’t be in the book. It contains too many pictures, which becomes more of a concern in print. There will be a few of the heavily illustrated entries in the book, but we had to balance those with others that don’t depend on images.

Whether books based on film and other media-related blogs will become a lasting genre has yet to be seen. Perhaps after a period of adjustment to the Internet as a venue for film criticism, we will return to the practice of the 1960s and 1970s, when Andrew Sarris, Pauline Kael, and other critics routinely saw their material collected as books. We might end up concluding that the Internet has not harmed books in the way that it has some newspapers and magazines.

If blog-based books do catch on, they will provide further counter-evidence to the notion that film criticism is dying out. If they don’t, the failure won’t prove that film criticism is dead, only that now it probably flourishes best online.

[March 22: Coincidentally, TV historian and critic Jason Mittell posted a related entry on his blog today. It’s entitled “Why a Book?” and ponders the pros and cons of publishing a scholarly book or putting the same material online. The piece doesn’t deal with the idea of a book collecting blog entries, but it touches on factors like long-range availability.]

Film criticism: Always declining, never quite falling

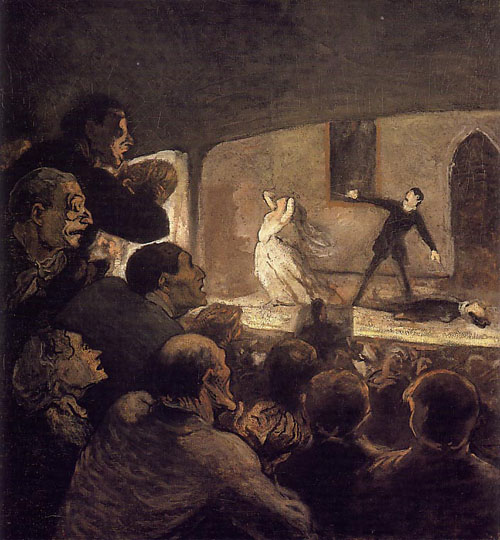

Daumier, Le mélodrame (1860-64)

DB here:

Before the Internets, did people fret as much about movie criticism as they do now? The dialogue has become as predictable as a minuet at Versailles.

Film criticism is dead.

No, it’s not! It’s alive and well on the Web.

Hah! Call that criticism? Nobody can be a movie critic unless they (a) write for print publication; (b) have been doing it for x years; (c) are a member of a critics’ professional society; and/ or (d) get paid for it.

Well, the track record of the official movie critics isn’t that great. Most of their writings are forgotten the minute they’re published.

Infinitely more awful is what you read on the Net. At least print critics kept up standards; there were gatekeepers (also called editors) and a literate public.

The result being….? When has a print critic of recent years equaled the greats of the past—Agee, Farber, Sarris, Kael?

Same thing goes for the Net. Blogs and websites don’t show me anything like that level of achievement. What I see is amateur hour.

Yeah? Well, bloggers and netwriters have passion!

But not a passion for using Spellcheck.

So if print criticism is so valuable, how come all those professional critics are getting fired?

Film criticism is dead.

Repeat as often as you like.

I thought I had watched this rondelay often enough from the wallflower section, but I got dragged onto the dance floor by Tom Doherty. In his piece for the Chronicle of Higher Education, Tom offered another eulogy for serious film criticism. Dead again, as Jim Emerson notes; killed by those wretched netizens.

To watch their backs and retain their 401(k)’s, most print critics have been forced into sleeping with the enemy. As a form of ancillary outreach, blogs, podcasts, and chat-room discussions have become a required part of the job description for print reviewers. Or maybe the print part of the gig is now the ancillary outreach.

Feeling the same heat, academic critics have also plunged into the brash new world. The film-studies panjandrum David Bordwell—think Knowles with chops in postmodern theory—runs one of the most closely watched blogs at David Bordwell’s Website on Cinema (http://davidbordwell.net/blog). The impact of the academic bloggers on Hollywood’s box-office gross is negligible (sorry, David), but the online work of the digital hordes is already making a substantial contribution to film scholarship—in the spirited parry and thrust of the dialogues, in the instant retrieval of past research, and in the factoid jackpots provided by the film databases.

I’m sure Tom means to be complimentary, but just to get mundane: No heat forced Kristin and me to the Web. I set up a bare-bones site in 2000, including a vitae and a statement about what studying film meant to me, because people were sometimes writing me asking for such information. Then, inspired by Philip Steadman’s stylish site extending the arguments in his book Vermeer’s Camera, I used mine to supplement my books, putting in corrections, second thoughts, and pictures. Then I began to write longish essays that build on things in the books.

When I retired in 2006, Kristin and I decided to recast the site as a supplement to our best-known book, Film Art: An Introduction. Our publisher McGraw-Hill funded an upgrade. But our efforts quickly went beyond spinning off the textbook. We treated Observations as our own magazine, with no pesky editors to tell us that a piece was too long or had too many stills. It offered a way to get our ideas out to a new audience, or maybe a bigger one. Just as important, after years spent writing books, I enjoy the recreation of writing shorter pieces. When you’re 62, sprints look better than marathons. Actually, because I’m a compulsive overwriter, some of my blog-sprints are like marathons.

Unhappily, none of this enhanced our 401(k)s.

Some other quibbles: Tom intended “panjandrum” as praise, but as many friends have pointed out, I’m probably the last person you’d associate with PoMo. I’m stuck in pre-post-modernism. Still, Tom is right on one point. My efforts to erode the box-office takings of Babel, The Departed, and The Dark Knight failed utterly. On the other hand, I may have considerably boosted Cloverfield’s first-dollar gross.

Nothing if not critical

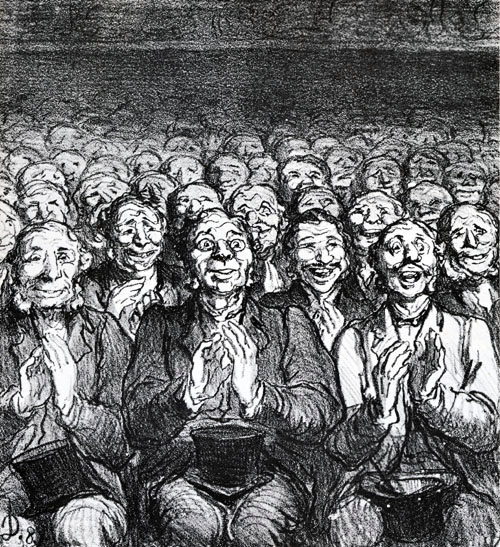

Daumier, Les critiques (1862)

Tom’s piece, its place of publication, the comments on it, and his reply to those comments invite me to revive some points I made around this season in 2008 and 2009. (Is it a rite of spring?)

Film criticism takes many forms. Tom identifies criticism with being paid to review movies that have just come out. This is a form of arts journalism, and like all journalism it is being squeezed by the decline in advertising revenue. So yes, print-based paid reviewing is waning.

But criticism includes more activities than rapid-response reviewing. It includes what we might call haute journalism, as practiced in literary quarterlies, film magazines like Cineaste and Cinema Scope, and even occasionally in the New York Review of Books (which just got around to noticing Sokurov’s 2005 The Sun). There’s also reseach-based criticism, published in specialized venues like Cinema Journal and in semi-specialized journals like Film Quarterly (which seems to be moving toward haute journalism). And of course academics have written whole volumes of film criticism—through-composed books, not collections of published reviews.

Each of these modes of criticism has its own conventions. I try to characterize them here. I think Tom should have made some of these distinctions, because it doesn’t help film culture to encourage readers of the Chronicle to limit their conception of criticism to what they get in The New Yorker or Salon.

Insofar as we think of criticism as evaluation, we need to distinguish between taste (preferences, educated or not) and criteria for excellence. I may like a film a lot, but that doesn’t make it good. For arguments, go here again. Criteria are intersubjective standards that we can discuss; taste is what you feel in your bones. A critical piece that merits serious thinking tends to appeal to criteria that readers can recognize, and dispute if they choose.

Enough with the love, already. My only real quarrel with Gerry Peary’s film For the Love of Movies is that it seems to place “love of cinema” at the center of the critical activity. But everybody loves film. The real question is: What does this love lead to? Gossip? Infighting and insults? A desire to take chances and watch films you might hate? A desire to stretch and nuance one’s viewing? An urge to learn something subtle about cinema more generally?

Opinions need balancing with information and ideas. The best critics wear their knowledge lightly, but it’s there. To be able to compare films delicately, to trace their historical antecedents, to explain the creative craft of cinema to non-specialists: the critical essay is an ideal vehicle for such information. The critic is, in this respect, a teacher.

Which means that the critic traffics in ideas too. A critic of lasting value offers a vision of cinema, of the arts more generally, of society or politics or something beyond the individual movie. For Sarris, the key idea was directorial authorship. For Parker Tyler, it was the idea that popular culture spasmodically threw up surrealistic material. For Farber it was the prospect that the studio system nurtured films, or moments, that hinted at speed, harshness, and darkness. Sontag clung to the hope that cinema could carry on the program of post-World-War-II modernism. For Ebert, what seems central is the belief that cinema can yield humane wisdom that forms a guide for living. Beyond our shores there were Arnheim, Bazin, Eisenstein (yes, he wrote film criticism), the Cahiers and Positif crews, and many more. Their powerful and provocative ideas yielded new ways to think about any movie.

Last year I moderated an Ebertfest panel consisting of a dozen or so critics. A student from the audience said he wanted to be a critic too. Instead of advising him to get into a more financially rewarding form of endeavor, like selling consumer electronics off the back of a truck, the panelists encouraged him. This form of altruism, in which you help people to become your competitor, is alarmingly common in the arts.

A moderator doesn’t get to talk much, so I couldn’t respond. What I wanted to say was: Forget about becoming a film critic. Become an intellectual, a person to whom ideas matter. Read in history, science, politics, and the arts generally. Develop your own ideas, and see what sparks they strike in relation to films.

Writing style is overrated. Many people think that good reviewing amounts to personal opinions whipped up in frothy prose. Perhaps the snazzy styles of Farber and Kael have led people to weight style too much. Granted, the Web has revealed that a lot of people are excellent writers, and without the Web they would probably never have found an audience. Although lively writing is always welcome, it gets heft and endurance through its arguments, and that comes back to ideas and information as much as opinion.

Hollywood, still declining

As often happens, a current controversy sends me backward, and to books. Ezra Goodman’s Fifty-Year Decline and Fall of Hollywood was published in the momentous year 1960, as was Beth Day’s This Was Hollywood. Both wrote finis to the glory days of American studio cinema. But if Day was nostalgic, Goodman was sour, and racy.

He worked as reporter, publicist, and reviewer, most notably for Time. By 1960, he must have felt he never needed an LA job again, so he castigates every specimen of Hollywoodite, from press agents to stars. Buddy Adler, who for a while ran production at Twentieth Century-Fox was no more than “a dutiful office boy.” Humphrey Bogart had “as a result of four marriages, innumerable bouts with the bottle, and a paucity of food and sleep developed what was described as a look of intelligent depravity. . . .”

Goodman includes a long chapter on film reviewers, which launches with a decidedly contemporary ring:

It has been said that there are sometimes more clichés in movie reviews than in the movies they are discussing. Sample review phrases: “sure-fire,” “stunning,” “taut with suspense,” “lavish and exciting,” “sumptuous,” “captures the imagination,” “moving,” “significant drama,” “sheer screen artistry,” “uncommonly good performance,” “dramatic urgency,” “enormous compulsion,” “spectacular finish,” and once in a while, “ineptly directed,” “singularly dull.”

Fifty years later, Goodman would have to add jaw-dropping, adrenalin-charged, mind-bending, hellish/ hellacious, resonance/ resonate, lush, dark, incredible, intensely personal, pitch-perfect, and our two all-purpose adjectives of praise, amazing and terrific. You’d think that we were staggering around astounded all the time.

Yet reading Fifty-Year Decline and Fall confirms my hunch that we have made progress. I would say that the best film writing in all registers–daily/ weekly reviewing, haute journalism, “think pieces,” personal essays, research studies, whether on the web or off– is much better today than it was in Goodman’s era. Then the New York Times had Bosley Crowther; now it has Dargis and Scott. Richard Schickel has hurt his reputation with some insulting remarks he made recently, but read his book on Fairbanks, His Picture in the Papers, or his scathing The Disney Version, and you’ll find a keen eye and a nonconformist intelligence. Riding above the oceanic fizz of infotainment, there are many sharp writers both journalistic and academic. Start clicking our link-list for examples.

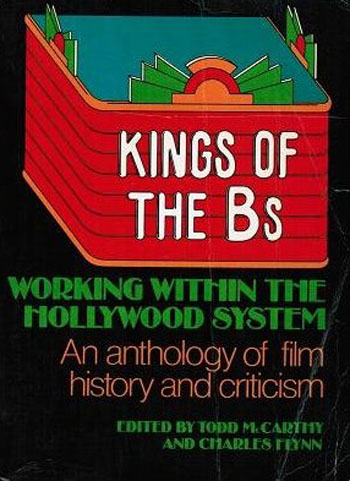

Which makes it all the more lamentable that two of our finest writers have lost their platform. Todd McCarthy’s work for Variety long exemplified the virtues I’ve itemized. He writes a brisk prose that isn’t showoffish. His reviews, often in a few deft words, situate the film historically; he’s one of those guys who has simply seen and read everything. He has as well a guiding idea of cinema—roughly, I think, the premise that straightforward classical storytelling is an inexhaustible resource—but he doesn’t deploy it as a bludgeon. McCarthy’s respect for studio history and the tradition of expressive narrative can be found in his and Charles Flynn’s indispensible collection Kings of the Bs (where you can see what a Republic budget sheet looked like) and in his biography of Howard Hawks. There are also his documentaries on filmmaking (e.g., Visions of Light) and film culture (Man of Cinema: Pierre Rissient), which allow him the leisure to probe subjects in depth.

Or consider Derek Elley. He is one of the most knowledgeable writers on Asian cinema, and his reviews skillfully tie a new film to a trend or earlier work by the same director. Few critics have his ability to supply a translation of a Chinese film’s original title, or to explain a crucial local custom. By dismissing McCarthy and Elley as contract writers, Variety has dealt a blow to informative, thoughtful film writing, whether you call it criticism or not.

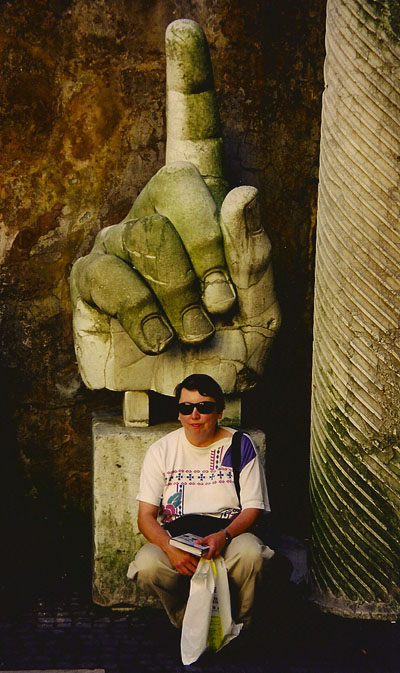

Daumier, One says that the Parisians. . . (1864)

Her design for living

Kristin in Rome, 1997, in front of a “recent” hand from a colossal statue of Constantine. The Amarna statuary fragments she studies are twice as old.

DB here:

Kristin is in the spotlight today, and why not? She’s too modest to boast about all the good things coming her way, but I have no shame.

First, our web tsarina Meg Hamel recently installed, in the column on the left, Kristin’s 1985 book Exporting Entertainment: America in the World Film Market 1907-1934. It was never really available in the US and went out of print fairly quickly. Vito Adriaensens of Antwerp kindly scanned it to pdf and made it available for us. So we make it available to you. More about Exporting Entertainment later.

Second, Kristin is not only a film historian but a scholar of ancient Egyptian art, specifically of the Amarna period. (These are the years of Akhenaten and Nefertiti and their highly unsuccessful experiment in monotheism.) Every year she goes to Egypt to participate in an expedition that maps and excavates the city of Amarna. In recent years she’s focused on statuary, about which she’s given papers and published articles. Now we’ve learned that she has won a Sylvan C. Coleman and Pamela Coleman Memorial Fellowship to work in the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s collection for a month during the next academic year. So at some point then we’ll both be blogging from NYC. Think of the RKO Radio tower sending our signals to a tiny world below.

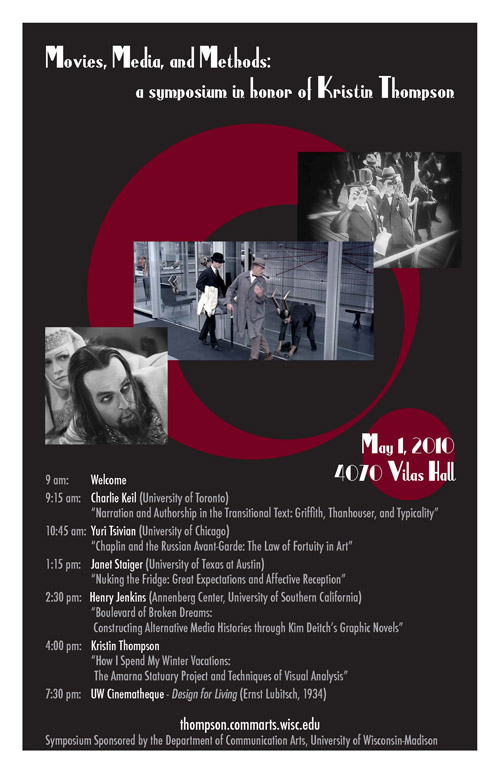

Third, she is about to turn 60, and in her honor the Communication Arts Department is sponsoring a day-long symposium. On 1 May we’ll be hosting Henry Jenkins, Charlie Keil, Janet Staiger, and Yuri Tsivian to give talks on topics related to her career interests. Kristin’s talk will survey her Egyptological work, with observations on how she has applied analytical methods she developed in her film research. You can get all the information about the event, as well as find places to stay in Madison, here.

Kristin came to Madison in 1973, a very good moment. Whatever you were interested in, from radical politics to chess to necromancy (there was a witchcraft paraphernalia shop off State Street), you could find plenty of people to obsess with you. Film was one such obsession.

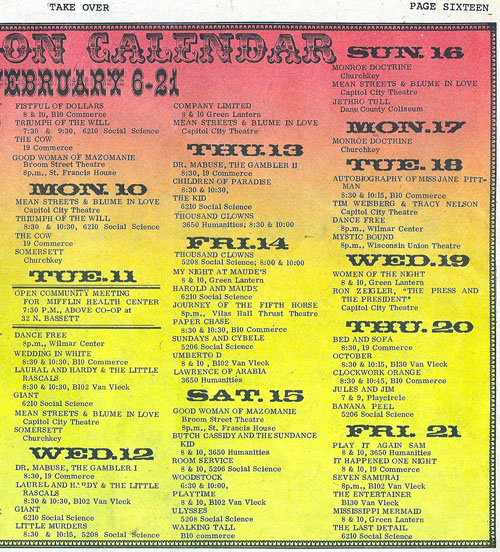

The campus boasted about twenty registered film societies, some screening several shows a week. Fertile Valley, the Green Lantern, Wisconsin Film Society, Hal 2000, and many others came and went, showing 16mm films in big classrooms in those days before home video. Without the internet, publicity was executed through posters stapled to kiosks, and the fight for space could get rough. Posters were torn down or set on fire; a charred kiosk was a common sight. Another trick was to call up distributors and cancel your rivals’ bookings. One film-club macher reported that a competitor had cut his brake-lines.

What could you see? A sample is above. What it doesn’t show is that in an earlier weekend of February of 1975, your menu included Take the Money and Run, The Lovers, Ray’s The Adversary, Page of Madness, Fritz the Cat, The Ruling Class, Dovzhenko’s Shors, Chaney’s Hunchback of Notre Dame, American Graffiti, Wedding in Blood, Pat and Mike, Camille, Yojimbo, Faces, Days and Nights in the Forest, King of Hearts (a perennial), Sahara, The Fox, Day of the Jackal, Dumbo, Investigation of a Citizen above Suspicion, Slaughterhouse-Five, Mean Streets, A Fistful of Dollars, Triumph of the Will, and The Cow. Not counting the films we were showing in our courses.

In addition, there was the Wisconsin Center for Film and Theater Research, recently endowed with thousands of prints of classic Warners, RKO, and Monogram titles. (There were also TV shows, thousands of document files, and nearly two million still photos.) When Kristin got here she immediately signed up to watch all those items she had been dying to see. She suggested that the Center needed flatbed viewers to do justice to the collection, and director Tino Balio promptly bought some. Those Steenbecks are still in use.

Out of the film societies and the WCFTR collection came The Velvet Light Trap, probably the most famous student film magazine in America. Today it’s an academic journal, though still edited by grad students. Back then it was more off-road, steered by cinephiles only loosely registered at the university. Using the documents and films in the WCFTR collection, they plunged into in-depth research into American studio cinema, and the result was a pioneering string of special-topics issues. When I go into a Parisian bookstore and say I’m from Madison, the owner’s eyes light up: Ah, oui, le Velvet Light Trap.

Out of the film societies and the WCFTR collection came The Velvet Light Trap, probably the most famous student film magazine in America. Today it’s an academic journal, though still edited by grad students. Back then it was more off-road, steered by cinephiles only loosely registered at the university. Using the documents and films in the WCFTR collection, they plunged into in-depth research into American studio cinema, and the result was a pioneering string of special-topics issues. When I go into a Parisian bookstore and say I’m from Madison, the owner’s eyes light up: Ah, oui, le Velvet Light Trap.

Above all there were the people. The department had only three film studies profs–Tino, Russell Merritt, and me–though eventually Jeanne Allen and Joe Anderson joined us. Posses of other experts were roaming the streets, running film societies, writing for The Daily Cardinal, authoring books, and editing the Light Trap. Who? Russell Campbell, John Davis, Susan Dalton, Tom Flinn, Tim Onosko, Gerry Perry, Danny Peary, Pat McGilligan, Mark Bergman, Sid Chatterjee, Richard Lippe, Harry Reed, Michael Wilmington, Joe McBride, Karyn Kay, Reid Rosefelt, Dean Kuehn, Samantha Coughlin, and Bill Banning. Most of these were undergraduates, but Maureen Turim and Diane Waldman and Douglas Gomery and Frank Scheide and Peter Lehman and Marilyn Campbell and Roxanne Glasberg and other grad students could be found hanging out with them. A great many of this crew went on to careers as writers, teachers, scholars, programmers, filmmakers, and film entrepreneurs.

Into the mix went film artists like Jim Benning, Bette Gordon, and Michelle Citron. There were film collectors too; one owned a 70mm print of 2001 and didn’t care that he could never screen it. ZAZ, aka the Zucker brothers and Jim Abrahams, were concocting Kentucky Fried Theater. Andrew Bergman had recently published We’re in the Money, and soon Werner Herzog would be in Plainfield waiting for Errol Morris to help him dig up Ed Gein’s grave. Set it all to the musical stylings of R. Cameron Monschein, who once led an orchestra the whole frenzied way through Intolerance. The 70s in Madison were more than disco and the oil embargo. (To catch up on some Mad City movie folk, go here.)

These young bravos worked with the same manic passion as today’s bloggers. The purpose wasn’t profit, but living in sin with the movies. Film society mavens drove to Chicago for 48-hour marathons mounted by distributors. Traditions and cults sprang up: Sam Fuller double features, noir weekends, hours of debates in programming committees. Why couldn’t Curtiz be seen as the equal of Hawks? Why weren’t more Siodmak Universals available for rental? Was Johnny Guitar the best movie ever made, or just one of the three best?

There was local pride as well. Nick Ray had come from Wisconsin, and so had Joseph Losey, not to mention Orson Welles (who claimed, however, that he was conceived in Buenos Aires and thus Latin American). During my job interview, Ray came to visit wearing an eye patch. It shifted from eye to eye as lighting conditions changed. When he showed a student how to set up a shot, he bent over the viewfinder and lifted the patch to peer in. Was he saving one eye just for shooting?

In the big world outside, modern film studies was emerging and incorporating theories coming from Paris and London. Partly in order to teach myself what was going on, I mounted courses centering on semiotics, structuralism, Russian Formalism, and Marxist/ feminist ideological critique.

Back in placid Iowa City, where Kristin got her MA in film studies and I my Ph.D., we grad students had seen our mission clearly. Steeped in theory, we pledged to make film studies something intellectually serious: a genuine research enterprise, not mere cinephilia. Madison was the perfect challenge. Here cinephilia was raised to the level of thermonuclear negotiation, backed with batteries of memos, scripts, and scenes from obscure B-pictures. Confronted with a maniacal film culture and a vast archive, Kristin and I realized that there was so much to know–so many films, so much historical context–that any theory might be killed by the right fact.

Watch a broad range of movies; look as closely as you can at the films and their proximate and pertinent contexts; build your generalizations with an eye on the details. Our aim became a mixture of analysis, historical research, and theories sensitively contoured to both. The noisy irreverence of Mad City, where a former SDS leader had just been elected mayor and city alders could be arrested for setting bonfires on Halloween, wouldn’t let you stay stuffy long.

Kristin’s work in film studies would be instantly recognizable to humanists studying the arts. Essentially, she tries to get to know a film as intimately as possible, in its formal dimensions–its use of plot and story, its manipulations of film technique. I suppose she’s best known for developing a perspective she called Neoformalism, an extension of ideas from the Russian Formalists. Armed with these theories, she has studied principles of narrative in Storytelling in the New Hollywood and Storytelling in Film and Television. She has probed film style in Herr Lubitsch Goes to Hollywood and her sections of The Classical Hollywood Cinema. And she has examined narrative and style together in her book on Eisenstein’s Ivan the Terrible and the essays in Breaking the Glass Armor.

Contrary to what commonsense understanding of “formalism” implies, she has always framed her questions about form and style in a historical context. She situates classic and contemporary Hollywood within changes in the film industry–the development of early storytelling out of theatre and literature, or current trends responding to franchises and tentpole films. For her, Lubitsch’s silent work links the older-style postwar German cinema and the more innovative techniques of Hollywood. She situates Tati, Ozu, Eisenstein, and other directors in the broad context of international developments, while keeping a focus on their unique uses of the film medium.

Perhaps her most ambitious accomplishment in this vein is her contribution to Film History: An Introduction. She wrote most of the book’s first half, and though I’m aware of the faults of my sections, I find hers splendid. After twenty years of research, she produced the most nuanced account we have yet seen of the international development of artistic trends in American and European silent film.

Kristin has also illuminated the history of the international film industry. Everybody knows that Hollywood dominates world film markets. The interesting question is: How did this happen? Exporting Entertainment provides some surprising answers by situating film traffic in the context of international trade and changing business strategies. One twist: the importance of the Latin American market. The book also opened up inquiry into “Film Europe,” a 1920s international trend that tried to block Hollywood’s power. In all, Exporting Entertainment led other researchers to pursue the question of film trade, and I was gratified to see that Sir David Puttnam’s diagnosis of the European film industry, Undeclared War, made use of Kristin’s research.

More recently, Kristin has turned her attention to the contemporary industry, the main result of which has been The Frodo Franchise, a study of how a tentpole trilogy and its ancillaries were made, marketed, and consumed. Her love of Tolkien and her respect for Peter Jackson’s desire to do LotR justice led her to study this massive enterprise as an example of moviemaking in the age of winning the weekend and satisfying fans on the internet. She maintains her Frodo Franchise blog on a wing of this site.

Most readers of this blog know Kristin as a film scholar. They may be surprised to learn that she also wrote a book on P. G. Wodehouse’s Bertie Wooster books. Wooster Proposes, Jeeves Disposes; or, Le Mot Juste is a remarkable piece of literary criticism. Here she shows how Wodehouse developed his own templates for plot structure and style. Again, the analysis is grounded in research–in this case, among Wodehouse’s papers. So assiduously did she plumb Plum that she became the official archivist of the Wodehouse estate. This is also, page for page, the funniest book she has yet written.

Her Egyptological work is no joke, though, and she has become one of the world’s experts on Amarna statues. She has published articles and given talks at the British Museum and other venues. Soon she’ll trek off for her ninth season at Amarna. There, joined by her collaborator, a curator at the Metropolitan, she’ll study the thousands of fragments that she’s registered in the workroom seen above. It’s preparation for a hefty tome on the statuary in the ancient city.

You can learn more about Kristin’s career here, in her own words. These are mine, and extravagant as they are, they don’t do justice to her searching intelligence, her persistent effort to answer hard questions, and her patience in putting up with my follies and delusions. You’d be welcome to visit her symposium and see her, and people who admire her, in action. While you’re here, you can watch a restored print of Design for Living, by one of her favorite directors, screening at our Cinematheque. In 35mm, of course. We can’t shame our heritage.

Poster design by Heather Heckman. Check out our Facebook page too.

Propinquities

Jinhee Choi, Centre Pompidou, January 2010.

Propinquity: Nearness, closeness, proximity: a. in space: Neighborhood 1460. b. in blood or relationship: Near or close kinship, late ME. c. in nature, belief, etc.: Similarity, affinity 1586. In time: Near approach, nearness 1646. —Oxford Universal Dictionary

DB here:

In any art, tools and tasks matter. From the first edition of Film Art (1979) to the present, our introduction to film aesthetics starts with an overview of film production. How is production organized within the commercial industry, or within a more artisanal mode? What freedom and constraints are afforded within the institutions of filmmaking? How does current technology support or limit what the filmmaker can do? And how do filmmakers explain what they’re doing—not just as personal proclivities but as rhetorical “framings” that lead us to think of their work in a particular way?

Some would call this approach “formalism,” but that label doesn’t capture it. Traditionally formalism refers to studying an artwork intrinsically, as a self-sufficient object. In this sense, our perspective is anti-formalist: We look outside the movie to the proximate conditions that shape its form, style, subjects, and themes.

More literary-minded film scholars have sometimes been impatient with this perspective. Yet in the history of painting and music, it has yielded real advances in our knowledge. It continues to do so in film studies too, as I learned when we came back from Yurrrp to find some books awaiting us. (Kristin has already remarked on the stacks of DVDs that had accumulated.) Among these were books that illustrate the continuing value of situating film artistry in its most immediate context: the creative circumstances, the norms and preferred practices operating within traditions, the rationales that artists offer for their choices. Even better, the books were written by friends, so we have both intellectual and personal propinquity. I have always wanted to use the word propinquity in a piece of writing.

Memories of Murder (Bong Joon-ho).

Jinhee Choi’s The South Korean Film Renaissance: Local Hitmakers, Gobal Provocateurs is a wide-ranging survey of what some have called the “next Hong Kong”–a popular cinema of brash impact and technical polish, on display in JSA, Beat, Dirty Carnival, My Sassy Girl, and the like. But unlike Hong Kong, South Korea has a strong arthouse presence too, typified by Hong Sang-soo’s exercises in parallel narratives and thirtysomething social awkwardness. Between these poles stands what local critics called the “well-made” commercial film, as exemplified by Bong Joon-ho’s Memories of Murder.

Choi, a professor at the University of Kent, mixes analysis of cultural and industrial trends with consideration of crucial genres (notably the “high school film”) and major auteurs. She is the first scholar I know to explain changes in the Korean film industry as emerging from a dynamic among critics, filmmakers, private funding, and government sponsorship. A must, I would say, for anyone interested in current Asian film.

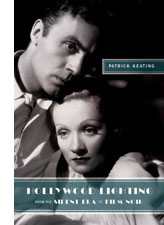

T-Men (Anthony Mann, cinematographer John Alton).

The South Korean Film Renaissance is matched by a work of equal subtlety, Patrick Keating’s Hollywood Lighting: From the Silent Era to Film Noir. Keating has an MFA in cinematography from USC, and his Ph. D. work concentrated on classical American cinema. His book captures the craft of the great studio cameramen, following not only what they said they were doing (in interviews and in the trade papers) but also what they actually did. He homes in on the contradictory demands facing artists who, they claimed over and over, had to serve the story. How do you claim artistry if your contribution is unnoticeable? This problem becomes acute with film noir, where the style is expected to come forward to a significant degree.

The South Korean Film Renaissance is matched by a work of equal subtlety, Patrick Keating’s Hollywood Lighting: From the Silent Era to Film Noir. Keating has an MFA in cinematography from USC, and his Ph. D. work concentrated on classical American cinema. His book captures the craft of the great studio cameramen, following not only what they said they were doing (in interviews and in the trade papers) but also what they actually did. He homes in on the contradictory demands facing artists who, they claimed over and over, had to serve the story. How do you claim artistry if your contribution is unnoticeable? This problem becomes acute with film noir, where the style is expected to come forward to a significant degree.

Keating scrutinizes the films with unprecedented care, tracing not only cameramen’s distinctive styles but showing that originality was always in tension with the conventional lighting demands of various genres and situtations. Many big names are here—John Seitz, Gregg Toland, John Alton—but the book also examines innovations coming from solid craftsmen like Arthur Lundin, who lit Girl Shy and other Harold Lloyd films. You won’t look at a studio movie the same way after you’ve digested Keating’s richly illustrated analyses.

Both Jinhee and Patrick were students here, and I directed the dissertations that eventually became these books. So of course I’m biased. But I think that any outside observer would agree that these monographs show the value of studying how film artistry and the film industry intertwine.

Blue (Krzysztof Kieslowski).

No less sensitive to the interplay of art and business is Patrick McGilligan’s Backstory 5: Interviews with Screenwriters of the 1990s. The collection is as illuminating as earlier installments have been. How could it not be, with career ruminations from Nora Ephron, John Hughes, David Koepp, Barry Levinson, John Sayles, et al.?

I’ve long found Pat’s Backstory volumes a treasury of information about Hollywood’s craft practices. Every conversation yields ideas about structure, style, and working methods. In this volume, for instance, Richard Lagravanese points out that scenes have become very short; with slower pacing in the studio days, scenes had time to breathe. And after claiming over and over that cinematic narration comes down to patterning story information, I was happy to read Tom Stoppard:

The whole art of movies and in plays is in the control of the flow of information to the audience. . . . how much information, when, how fast it comes. Certain things maybe have to be there three times.

In the studio days this last condition was called the Rule of Three: Say it once for the smart people, once for the average people, and once more for Slow Joe in the Back Row. Some things don’t change.

Pat McGilligan is also a Wisconsin alumnus, so to keep these notes from getting too incestuous, I’ll just mention that I know the distinguished musicologist David Neumeyer chiefly from his writing (though I have to confess I first met him when he visited . . . Madison). Along with coauthors James Buhler and Rob Deemer, David has published an excellent introduction to film sound. Hearing the Movies: Music and Sound in Film History is designed as a textbook, but it’s so well written that every movie lover would find it a pleasure to read.

Pat McGilligan is also a Wisconsin alumnus, so to keep these notes from getting too incestuous, I’ll just mention that I know the distinguished musicologist David Neumeyer chiefly from his writing (though I have to confess I first met him when he visited . . . Madison). Along with coauthors James Buhler and Rob Deemer, David has published an excellent introduction to film sound. Hearing the Movies: Music and Sound in Film History is designed as a textbook, but it’s so well written that every movie lover would find it a pleasure to read.

The examples run from the silent era (including Lady Windermere’s Fan, a favorite of this site) to Shadowlands, and while music is at the center of concern, speech and effects aren’t neglected. There’s a powerful analysis of the noises during one sequence of The Birds, and the authors pick a vivid example from Kieslowski’s Blue (above), in which Julie is shown listening to a man running through her apartment building; we never see the action that triggers her apprehension.

The authors provide a compact history of sound film technology, including many seldom-discussed topics. For instance, 1950s stereophonic film demanded bigger orchestras and more swelling scores, while separation among channels permitted scoring to be heavier, without muffling dialogue. Throughout, Neumayer and his coauthors balance concerns of form and style with business initiatives, such as the growth of the market for soundtrack albums and CDs (a topic first explored by another Wisconsite, Jeff Smith, in his dissertation book). Once more we can arrive at fine-grained explanations of why films look and sound as they do by examining the craft practices and industrial trends that bring movies into being.

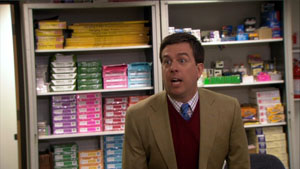

Watching back episodes of the American version of The Office recently, I’ve been struck by the premise it takes over from the UK original. This comedy of humors in Cubicle World is supposedly recorded in its entirety by an unseen film crew. I enjoy the clever way in which the show bends documentary techniques to the benefit of traditional fictional storytelling. The slightly rough handheld framings suggest authenticity, and the to-camera interviews permit maximal exposition by giving backstory or developing character or filling in missing action. The premise that an A and a B camera are capturing the doings at the Dunder Mifflin paper company permits classic shot/ reverse-shot cutting and matches on action.

The camera is uncannily prescient, always catching every gag and reaction shot; even private moments, like employees having sex, are glimpsed by these agile filmmakers. Above all, the camera coverage is more comprehensive than we can usually find in fly-on-the-wall filming. For instance, Dwight is preparing Michael for childbirth by mimicking a pregnant woman and Andy, behind him, tries to compete. Here are four successive shots, each one pretty funny.

Somehow the cameramen manage to supply a smooth cut-in to Andy, and that’s followed by a reaction shot, from a fresh angle, showing Jim watching. The range of viewpoints, implausible in a real filming situations, is often smoothed over by sound that overlaps the cuts, as in both documentary and fictional moviemaking. (See our essay on High School here to see how a genuine documentary uses these techniques.)

Of course I’m not faulting the makers of The Office for not rigidly imitating documentary conditions. Any such blend of fictional and nonfictional techniques will involve judgments about how far to go, as I indicate in an earlier post on Cloverfield. It’s just to acknowledge that TV visuals have their own conventions, and these can be creatively shaped for particular effects. We ought to expect that those conventions would encourage close analysis as easily as film traditions do. Jeremy Butler’s new book Television Style offers the best case I know for the claim that there is a distinct, and valuable, aesthetic of television.

Following his own study Television: Critical Methods and Applications (third edition, 2007) and paying homage to John Caldwell’s pioneering Televisuality, Butler gets down to the details of how various TV genres use sound and image. Butler’s conception of genres is admirably broad, considering dramas, sitcoms, soap operas, and commercials, each with its own range of audiovisual conventions and production practices. His discussion of types of television lighting complements Keating’s analysis; put these together and you have some real advances in our understanding of key differences and overlaps between film and video.

Kristin has met Jeremy, but I haven’t yet. In any case, Television Style shows that he’s a kindred spirit who’s made original contributions to this research tradition. Like Jinhee, Patrick, Pat, and David, he demonstrates that we can better grasp how media work if we study, patiently and in detail, the creative options open to film artists at specific points in history. He began thinking about these matters in 1979, as the photo attests.

Kristin has met Jeremy, but I haven’t yet. In any case, Television Style shows that he’s a kindred spirit who’s made original contributions to this research tradition. Like Jinhee, Patrick, Pat, and David, he demonstrates that we can better grasp how media work if we study, patiently and in detail, the creative options open to film artists at specific points in history. He began thinking about these matters in 1979, as the photo attests.

None of this is to say that artistic norms or industrial processes are cut off from the wider culture. Rather, as becomes very clear in all of these books, cultural developments are often filtered through just those norms and institutions.

For example, everybody knows that in classical studio cinema, women were usually lit differently from men. But Keating notices that often women’s lighting varies across a movie, depending on story situations. He goes on to make a subtler point: there was a greater range in lighting men’s faces. Men could be lit in more varied ways according to the changing mood of the action, while lighting on women was a compromise between two craft norms: let the lighting suit the story’s mood, and endow women with a glamorous look. The fluctuations in the imagery stem from adjusting cultural stereotypes to the demands of Hollywood’s stylistic conventions.

Careful studies like these, alert to fine-grained qualities in the films and the conditions that create them, can advance our understanding of how movies work. Pursuing these matters takes us beyond both the movie in isolation and generalizations about the broader culture; we’re led to examine the filmmaker’s tasks and tools.

Resurrection of the Little Match Girl (Jang Sun-woo, 2002).