That reminds me …

Wednesday | April 14, 2010 open printable version

open printable version

Enter the Frog Footman in Alice

Kristin here:

One film I can’t work up much enthusiasm about is everywhere, and another I very much want to see doesn’t seem to have a North American distributor. Luckily each reminds me of an older film that isn’t widely enough known. This seems like the perfect chance to point them out.

Recently the latest Screen International, in its new monthly format, arrived, with literally back-to-back reviews of the two films: Tim Burton’s Alice in Wonderland and Sylvain Chomet’s The Illusionist.

Let me say first off that Johnny Depp looks great in eyeliner, as in Pirates of the Caribbean. He looks positively grotesque with pink lips and raccoon eyes. Of course, grotesque could work well for Alice, especially as adapted by Burton. Yet the reviews suggest that the film is actually tamer than one would expect. Screen International’s Brent Simon calls Burton’s film: “A gorgeously mounted but fundamentally humdrum telling of Lewis Carroll’s fantasy novels” (March 2010 issue, p. 61). Variety’s Todd McCarthy makes a similar remark: “But for all its clever design, beguiling creatures and witty actors, the picture feels far more conventional than it should; it’s a Disney film illustrated by Burton, rather than a Burton film that happens to be released by Disney.”

Back in 1951 Disney did a fine version of Alice in Wonderland, one which does capture something of the lunacy of the original. It also benefited from the talent of some of the studios’ best artists, including Mary Blair. Always worth going back to.

But if one wants a truly surrealist, unconventional adaptation, I doubt if anything can top Jan Švankmajer’s feature Něco z Alenky, aka Alice. David and I saw it in a theater when it was released in the U.S. in 1988. It was my first exposure to the great Czech surrealist animator, and we gradually caught up with his earlier films. At the time it had a considerable success on the art-cinema circuit, though I’m not sure how well known it is among younger film fans.

Švankmajer had used both live-action, as in his morbid documentary The Ossuary (1970), and stop-motion animation of objects, as in his brilliant, dark look at human relations, Dimensions of Dialogue (1982). DVD anthologies of his shorts are available. Kino Video’s “The Collected Shorts” volume isn’t as complete as its name may imply. It’s missing several films including The Last Trick, his first but far from least film, and what may be his very best, Jabberwocky (1971), a non-narrative short incorporating Carroll themes. If you’ve got a Region 2 or multi-standard player, opt instead for “Jan Švankmajer: The Complete Short Films,” from the British Film Institute. It has a third disc with extras.

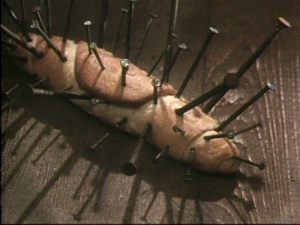

Alice is suffused with a marvelous imagination. Many of the characters are museum specimens. The White Rabbit begins as a stuffed creature in a Victorian glass case, freeing himself by pulling up the nails that keep him rigidly posed. Breadrolls sprout quills made of nails, and unnatural skeletons of creatures straight out of a Bosch painting creep about.

Švankmajer takes advantage of the mingling of two-dimensional figures based on playing cards and three-dimensional figures in ways that few adapters of Alice in Wonderland have managed, as when the White Rabbit passes the Queen of Hearts in a stage setting built of painted flats:

The Mad Hatter in Švankmajer’s film is definitely not Johnny Depp. He’s an antique wooden puppet of the sort that often crops up in the filmmaker’s work. He’s also not as loquacious as the chap in the book. The March Hare, who is definitely mad, steals the scene from him. Buttering a watch’s innards is a pure Švankmajerian gesture.

Alice was Švankmajer’s first feature film. In it he mixed live-action in with the stop-action more than in most of his shorts, presumably in part as a way to save money in making a much longer film. When Alice is full-size, she is played by a real girl, but when she shrinks she becomes a pixilated doll. It works well in this case, but the filmmaker depended more and more on live-action in his later features, like Faust (1994), with animated interludes becoming rarer and rarer. I found these features less entertaining and original and more heavy-handed in their social commentary. (The shorts contained vicious satire, but it was often rendered in bizarre, striking ways that made it palatable.) After thoroughly disliking Conspirators of Pleasure (1996), I gave up on his new films and stuck with the old ones. He’s making one now, called Surviving Life, which he apparently has said will be his last.

A final word on Alice. As should be obvious, this isn’t your charming adaptation for children, at least small ones. Alice points that out during the credits, “Now you will see a film made for children. Perhaps.” Most kids these days seem to be more hard-boiled than in my youth, but seeing this film at age 10 would have left me with nightmares. The White Rabbit, scarier than any fuzzy little bunny I’ve ever seen (including the one in Monty Python and the Holy Grail), runs around with scissors, quite willing to obey the Queen of Hearts’s order, “Off with her head!”; the little skeleton creatures crawl over Alice; and creepy glass eyes give staring life to inanimate objects like the Frog Footman or the sock that turns into the Caterpillar:

They tend to stare right out at us, too.

Tati on Parade

Most readers of this blog will be familiar with the great Jacques Tati. But it was news to me that he had left an unproduced screenplay, finished in the 1950s and now adapted by French animator Sylvain Chomet. Those who saw Chomet’s first feature, the 2D animated film The Triplets of Belleville (2003), probably noticed the occasional Tati homage lurking in the backgrounds and on the walls. Now Chomet’s admiration for Tati has emerged front and center in his second animated feature. The Illusionist‘s protagonist is modeled directly on Tati; he’s a old-fashioned magician eking out a living in the fading world of music-halls. (The Russian trailer has been posted here; apparently that’s the only footage on the internet so far.)

The Illusionist premiered at the Berlin Film Festival this year and met with a warm reception from critics. Writing in Screen International, Lisa Nesselson calls it “a delightfully bittersweet valentine to the music-hall tradition” and says that its animation “simply could not be better” (March, 2010 issue, p. 62). Leslie Felperin’s Variety reviews dubs it “a very happy marriage of Tati’s and Chomet’s distinctive artistic sensibilities.”

While we are waiting for an American distributor to pick up the film (ahem!), let me recommend Tati’s least-known feature. After his financial difficulties in the wake of Play Time‘s high budget and tepid box-office performance, the director set out to make Traffic, his last film featuring his M. Hulot character. Funding on this film collapsed midway through shooting, but Swedish TV stepped in and bailed the production out. Traffic came out in 1971, and in exchange for the assistance Tati made the 85-minute telefilm Parade (1974).

It has been available on French DVD (now out of print), but now the British Film Institute has released its own edition. The transfer isn’t the greatest, though it seems to be the same or similar to the French version. It smooths over the peculiarities of the original film. David and I saw it in 35mm in Brussels (where we also saw The Triplets of Belleville). It was obvious that while most of the film had been shot on somewhat fuzzy video in front of a live audience, some acts had been staged in a studio on crystal-clear 35mm. It was an oddly mixed format for an odd film. The BFI version also features optional English subtitles. Given the paucity of audible speech, they don’t seem vital.

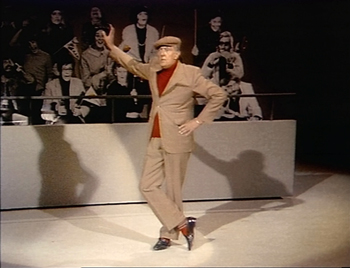

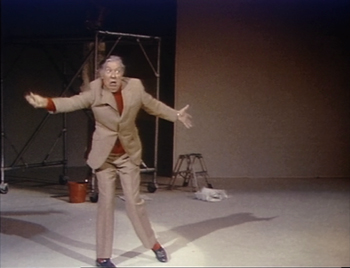

After the audience files in and takes their seats and an opening parade introduces the main acts, Tati steps forward as emcee and informs the spectators that they will be as much a part of the show as the performers onstage. Sure enough, the audience has been staged by Tati, accoutered in outrageous, colorful outfits and instructed to turn their heads back and forth rhythmically during his tennis routine or to bounce balloons around. Occasionally “ordinary” people from the stands step forward to challenge the acts onstage, trying and sometimes succeeding in out-doing them in magic or musical performances. The black-and-white life-size cutout people that had been used as extras in the backgrounds of scenes in Play Time return here as prominent members of the audience and even the stage acts. In the scene of Tati’s mime of a goalie (see below), the cutouts provide an unmoving backdrop to the action.

After the audience files in and takes their seats and an opening parade introduces the main acts, Tati steps forward as emcee and informs the spectators that they will be as much a part of the show as the performers onstage. Sure enough, the audience has been staged by Tati, accoutered in outrageous, colorful outfits and instructed to turn their heads back and forth rhythmically during his tennis routine or to bounce balloons around. Occasionally “ordinary” people from the stands step forward to challenge the acts onstage, trying and sometimes succeeding in out-doing them in magic or musical performances. The black-and-white life-size cutout people that had been used as extras in the backgrounds of scenes in Play Time return here as prominent members of the audience and even the stage acts. In the scene of Tati’s mime of a goalie (see below), the cutouts provide an unmoving backdrop to the action.

The BFI DVD includes a brief but informative booklet with essays by Philip Kemp and Jonathan Rosenbaum. As Kemp  points out, the acts out of which Tati built his film are, apart from himself, not much to boast about: “His colleagues’ juggling, acrobatics, and, literally, horseplay (much use is made of an upright piano that doubles as a vaulting-horse) are diverting but nothing special.” Yet that, I suspect, is part of the underlying strategy. The film is quite Tatiesque, despite its lack of M. Hulot or a real plot. The juxtaposition of the three separate spaces of the audience, the stage, and the carpenters’ shop directly abutting the performance space, allows the creation of the sort of visual jokes that Tati loves. It also permits a flow between roles, as when the “carpenters” emerge briefly to juggle with their brushes or to play their tools like xylophones before returning to work. All these performers are quite good, but really great acts would distract from the best act of all: Tati’s overflowing visual imagination.

points out, the acts out of which Tati built his film are, apart from himself, not much to boast about: “His colleagues’ juggling, acrobatics, and, literally, horseplay (much use is made of an upright piano that doubles as a vaulting-horse) are diverting but nothing special.” Yet that, I suspect, is part of the underlying strategy. The film is quite Tatiesque, despite its lack of M. Hulot or a real plot. The juxtaposition of the three separate spaces of the audience, the stage, and the carpenters’ shop directly abutting the performance space, allows the creation of the sort of visual jokes that Tati loves. It also permits a flow between roles, as when the “carpenters” emerge briefly to juggle with their brushes or to play their tools like xylophones before returning to work. All these performers are quite good, but really great acts would distract from the best act of all: Tati’s overflowing visual imagination.

Ultimately, though, the main boon of Parade was to preserve for posterity Tati’s famous series of sport-based pantomimes that he had developed in the 1930s, when he was a successful stage performer. He started off on the same music-hall stage that he celebrates in Parade and now, posthumously, in The Illusionist. Some of these mimes, such as the man-and-horse trick rider, the over-confident goalie, the over-the-hill boxer, or the disappointed fisherman (bottom) may have remained unchanged across Tati’s career. (After he became famous as a filmmaker and actor, he often had the chance to perform these brief skits on TV variety and talk shows.)

Horse-man

Goalie

Boxer between rounds

Tennis in slow motion

There’s one magic moment in these mimes, however, that Tati presumably updated. During the tennis match, he lapses briefly into slow motion. Not a slow motion achieved in the camera, which keeps running at normal speed. No, he mimes a player as seen in slow motion, quite convincingly and yet moving in ways that one wouldn’t consider possible for the human body. It’s hard to describe, but believe me, it’s amazing to watch.

Tati’s performances as the postman in Jour de fête or as Hulot in the four films featuring that character are usually not flashy. They’re designed to merge into the story and make the hero one of many amusing characters in an ensemble. But in Parade, with the pantomimes performed outside a narrative context and primarily against dark or blank white backgrounds, we can savor the man’s dazzling skill. His utter control of every gesture echoes his directorial mastery of every stylistic component of his films. In Parade, the moments when he tries to subdue a flapping fish before it escapes or when his head snaps back in reaction to an imaginary opponents’ blows are mindboggling in their precision. He was a great actor before he was a great filmmaker, and fortunately that early skill lingered long enough to be recorded.

Gone fishing