Archive for May 2010

It takes all kinds

Kristin here—

How many directors are there whose bad reviews just make you more eager to see their new films? I’m not at Cannes and haven’t seen Jean-Luc Godard’s Film socialisme. But I’ve read some negative reviews, mainly those by Roger Ebert and Todd McCarthy. Now I’m really hoping that Film socialisme shows up at the Vancouver International Film Festival this year. (Please, Mr. Franey? I promise to blog about it.)

As you can tell from my writings, I’m no pointy-headed intellectual who won’t watch anything without subtitles. I love much of Godard’s work and have analyzed two films from early in what a lot of people see as his late, obscurantist period (Tout va bien and Sauve qui peut (la vie) in Breaking the Glass Armor). But I also love popular cinema. If I made a top-ten-films list for 1982, both Mad Max II (aka The Road Warrior) and Passion (left and below) would be on it.

Of course, those are old films by most people’s standards. Godard’s films have gotten much more opaque since I wrote those essays. I wouldn’t dare to write about King Lear or Hélas pour moi. That’s partly because I don’t speak French, though a French friend of ours has assured us that that doesn’t help much. Here Godard thwarts the non-French-speaker further by not translating the dialogue. Variety‘s Jordan Mintzer describes the subtitles that appear in the film: “To add fuel to the fire, the English subtitles of “Film Socialism” do not perform their normal duties: Rather than translating the dialogue, they’re works of art in themselves, truncating or abstracting what’s spoken onscreen into the helmer’s infamous word assemblies (for example, “Do you want my opinion?” becomes “Aids Tools,” while a discussion about history and race is transformed into “German Jew Black”).” Mintzer’s review provides a long description of the film; he mentions how baffling it is but doesn’t offer any real value judgments on it. Like other reviews, though, it piques my interest in the film.

Since Godard has increasingly moved into video essays, I’ve not kept as close track of him. But I always look forward to seeing his occasional new features on the big screen. The man has a mysterious knack for making beautiful images out of the mundane. How could a shot of a distant airplane leaving a jet-trail across a blue sky be dramatic? Godard manages it in the first shot of Passion. (I won’t show a frame from that shot, since it depends on the passage of time for its effect.) His soundtracks are dense and playful. Every few years the man cobbles together an incomprehensible plot based on rather tired political ideas and turns out something so visually striking that it might as well be an experimental film. I’m willing to watch and listen hard without assuming that I’m obliged to strain to find a message. McCarthy comments, “More personally, I have become increasingly convinced that this is not a man whose views on anything do I want to take seriously. […]” Did we take his views all that seriously back when he was a Maoist? I didn’t, but La Chinoise is a terrific film.

That’s not my point, though. As Ebert’s and McCarthy’s reviews both mention there are devotees of Godard who will most likely enjoy and defend Film socialisme. Ebert: “I have not the slightest doubt it will all be explained by some of his defenders, or should I say disciples.” McCarthy says that Godard is one of an “ivory tower group whose work regularly turns up at festivals, is received with enthusiasm by the usual suspects and then is promptly ignored by everyone other than an easily identifiable inner circle of European and American acolytes.” (McCarthy’s review is entitled “Band of Insiders.”)

I’m not sure what’s wrong with being devoted to Godard, even to the point of defending films that may be obscure or even maddening. I personally haven’t enjoyed his more recent theatrical releases like Forever Mozart and Éloge pour l’amour as much as his earlier work, but they’re still better than most Hollywood, independent, and foreign art-house films. The man is pushing 80 and not likely to change, so live and let us acolytes live.

Not coming to a theater remotely near you

I’m not here to defend Godard—not yet, anyway. But on May 19, Roger posted an essay calling for more “Real Movies” to be made, essentially narratives based on psychologically intriguing characters in situations with which we can empathize. He doesn’t say so, but I suspect this idea was inspired in part by his reaction to Film socialisme. His examples of real movies are some of the films he’s enjoyed this year at Cannes. I haven’t seen those, either, but I’ve read enough of Roger’s writings and been to Ebertfest often enough to know he loves U. S. indie films like Frozen River and Goodbye Solo. Excellent films with fascinating characters, but they and most of the foreign-language films that get released in the U.S. play mostly at festivals and in art-houses, both of which tend to be confined to cities and college towns. I’m sure that such character-driven films would be more likely than Film socialisme to get booked into art-houses, but they wouldn’t wean Hollywood from its tentpole ways.

Even the films that play festivals and arouse great emotion and admiration in the audiences will seldom break through into the mainstream. There simply aren’t enough of those art-houses.

As with many of Roger’s posts, “A Campaign for Real Movies” has aroused comments from people complaining about the lack of an art-house within driving distance of where they live. Jeremy Chapman remarked:

But Roger, if they did that (“Real Movies”), then I’d return to the cinema. And those in charge of the movie industry have proven again and again that they don’t wish to see me there. They’d rather show regurgitated nonsense to people so desperate for some distraction from their lives that they’ll go even though they know that they’re watching rubbish.

If any of these films you mention play nearby, then I shall see them. But they won’t. Instead I’ll have the option of Avatar II or some remake of a movie that was quite good enough (or not) the first time it was made. I love the movies, but I’m so over the movie industry (at least in the US).

Talking to regulars at Ebertfest, one hears time and again that some of them journey across several states to have a quick, intense immersion in films that haven’t played near their homes. Similarly, many who post comments on Roger’s essays refer to having been limited to seeing indie and foreign films on DVDs or downloads from Netflix.

I completely sympathize with that problem. Even with Sundance’s six-screen multiplex and the University of Wisconsin’s Cinematheque series and Wisconsin Film Festival, most of the movies David and I see at events like Vancouver or Hong Kong don’t play here. Sundance has to book pop films on some of its screens to allow them to bring art films to the others. Right now Iron Man 2 and Sex in the City 2 are playing there, alongside The Secret in Their Eyes and Letters to Juliet. If that’s what it takes to keep the place going, then so be it.

I completely sympathize with that problem. Even with Sundance’s six-screen multiplex and the University of Wisconsin’s Cinematheque series and Wisconsin Film Festival, most of the movies David and I see at events like Vancouver or Hong Kong don’t play here. Sundance has to book pop films on some of its screens to allow them to bring art films to the others. Right now Iron Man 2 and Sex in the City 2 are playing there, alongside The Secret in Their Eyes and Letters to Juliet. If that’s what it takes to keep the place going, then so be it.

However much people decry the crassness of Hollywood—and there’s plenty of it to go around—or denounce audiences who only go to the latest CGI spectacle, the simple fact is that the market rules. Indeed, if there were a truly free market, we probably would see far fewer indie and foreign-language films. Film festivals are supported largely by sponsors, and the films they show are often wholly or partially subsidized by national governments. The festival circuit has long since become the primary market for a range of films that otherwise never reach audiences.

That may sound terrible to some, but consider the other arts. Some presses only publish books they hope will be best-sellers, while poetry and other specialist literature is relegated to small presses whose output doesn’t show up in Barnes & Noble. That’s very unlikely to change. Amazon and other online sales have been a shot in the arm for small presses, just as Netflix has made it far easier for people to see films they probably would not otherwise have access to. (Our plumber told me the other day that he had been watching a bunch of recent German films downloaded from Netflix. Well, that’s Madison, as we say; high educational level per capita. But most people have the same option, if they wish.)

Art-houses are scarce in small cities and towns, but such places are not likely to have opera houses either, or galleries with shows of major modern artists, or bookstores which offer 125,000 titles. (As I recall, that’s what Borders claimed to have when it first opened in Madison. Now they seem to be working on that many varieties of coffee.) Opera or ballet lovers are used to traveling to cities where they can see productions, and serious Wagner buffs aim to make the pilgrimage to Bayreuth at least once in their lives.

David and I are lucky. It’s vital to our work to keep up on world cinema, so now and then we travel to festivals and wallow in movies for a week or two. Quite a few civilians plan their vacations around such events, too. We’ve run into people in Vancouver who say they save up days off and take them during the festival. Naturally not everyone can do that, but not everybody can see the current Matisse exhibition in Chicago (closes June 20) or the recent lauded production of Shostakovich’s eccentric opera The Nose at the Metropolitan. I really wish I had seen The Nose, but I don’t really expect the production to play the Overture Center here.

To some people, film festivals might sound like rare events that inevitably take place far away, like the south of France. Those are the festivals that lure in the stars and get widespread coverage. But there are thousands of lesser-known festivals around the world, dedicated to every genre and length and nationality of cinema. For those who like to see old movies on the big screen, Italy offers two such festivals, Le Giornate del Cinema Muto (silent cinema) and Il Cinema Ritrovato (restored prints and retrospectives from nearly the entire span of cinema history; this year’s schedule should be posted soon). Last month in Los Angeles, Turner Classic Movies successfully launched its own festival of, yes, the classics. Ebertfest itself began with the laudable goal of bringing undeservedly overlooked films to small-city audiences, specifically Urbana-Champaign, Illinois. It was and is a great idea, and it would be wonderful if more towns in “fly-over country” had such festivals.

The films we don’t see

Usually when someone calls for more support of independent or foreign films, there seems to be an implicit assumption that all those films are deserving of support, invariably more so than Hollywood crowd-pleasers. If a filmmaker wants to make a film, he or she should be able to, right? But proportionately, there must be as many bad indie films as bad Hollywood films. Maybe more, because there are always lots of first-time filmmakers willing to max out their credit cards or put pressure on friends and relatives to “invest” in their project. There’s also far less of a barrier to entry, especially in the age of DYI technology.

True, the indie films we see seem better. By the time most of us see an indie film in an art cinema, it has been through a pitiless winnowing process. Sundance and other festivals reject all but a relatively small number of submitted films. A small number of those get picked up by a significant distributor. A small number of those are successful enough in the New York and LA markets to get booked into the art-house circuit and reach places like Madison. Yes, some worthy films get far less exposure than they deserve. But many more films that would give indies a bad name mercifully get relegated to direct-to-DVD, late-night cable, or worse. On the other hand, most mainstream films, no matter how dire their quality, get released to theaters. Their budgets are just too big to allow their producers to quietly slip them into the vault and forget about them.

The winnowing process for art-house fare happens on an international level as well. A prestige festival like Cannes dictates that a film they show cannot have had a festival screening or theatrical release outside its country of origin. Programmers for other festivals come to Cannes and cherry-pick the films they like for their own festivals. Toronto has come to serve a similar purpose, especially for North American festivals. Some films fall by the wayside, but the good ones attract a lot of programmers. These films show up at just about every festival. By the way, that kind of saturation booking of the year’s art-cinema favorites at many festivals means that the distributors are more and more often supplying digital copies of films to the second-tier events. Going to festivals is no longer a guarantee that you’ll be seeing a 35mm print projected in optimal conditions. At the 2009 Vancouver festival, I watched Elia Suleiman’s The Time that Remains twice, because it was a good 35mm print and I suspected that I’d never have another chance to see it that way.

To each film its proper venue

There’s no way that every deserving film will reach everyone who might admire it. Condemning the crowds who frequent the blockbusters won’t help open new screens to offbeat fare. If someone loves Avatar, as long as they keep their cell phones off, refrain from talking, and don’t rustle their candy-wrappers too loudly, as far I’m concerned they can go on believing that this is the best the cinema has to offer. Simply showing these audiences a film like A Serious Man, say, or Precious isn’t going to change their minds about what sort of cinema they prefer. To break through decades of viewing habits, such people would need to learn new ones, which takes time and effort. People’s tastes can be educated, but the odds are usually against it actually happening.

Finally, in defending art cinema against mainstream multiplex fare, commentators often cite Avatar or Transformers or the latest example of Hollywood’s venality and audience’s herd-like movie-going patterns. Yet every year major studio films come out that get four stars or thumbs up or green tomatoes. Last year, we had Cloudy with a Chance of Meatballs, Up, Inglourious Basterds, Coraline, and a few others that were well worth the price of a ticket. All of them did fairly well at the box-office while playing in multiplexes. Some readers might substitute other titles for the ones I’ve mentioned, but to deny that Hollywood is bringing us anything worth watching seems blinkered. As I said in 1999 at the end of Storytelling in the New Hollywood, where I criticized some aspects of recent filmmaking practices, “In recent years, more than ever, we need good cinema wherever we find it, and Hollywood continues to be one of its main sources.”

Ultimately my point is that in this stage in cinema history, international filmmaking has settled into a defined group of levels or modes. Hollywood gives us multiplex blockbusters and more modest genre items like horror films and comedies. They bring us the animated features that are among the gems of any year’s releases. Then there are the independent films and the foreign-language ones which together form festival/art-house fare. There are also the experimental films, which play in festivals and museums. The institutions that show all these sorts of films have similarly gelled into specialized kinds of venues suited to each type. A broad range of films is still being made. There are some few really good films in each category made each year. The question is not how many worthy films are getting made but how much trouble it takes to see them.

None of the current types of institutions is likely to change on its own. What will make a difference is the growing possibilities of distribution via the internet. Filmmakers who get turned down by film festivals can produce, promote, and sell their movies via DVD or downloads. True, recouping expenses that way is so far a dubious proposition; it’s probably easier to get into Sundance than to do that. As I mentioned, digital projection may make some festivals less attractive to die-hard film-on-film cinephiles. On the other hand, in some towns opera-lovers who can’t get to the big city now can see a digital broadcast of a major production each week at their local multiplex. Not as exciting as a trip to the city to see it live, but a lot cheaper and hence within the reach of a lot more people’s means. All sorts of other digital developments will change movie viewing in ways we can’t yet imagine.

_______________

Jim Emerson has been covering the Film socialisme battle of the reviews on Scanners, with quotes and links to the ones I mentioned and more. He also demonstrates that people have been baffled by Godard since Breathless, with reviews that “are, incredibly, the same ones he’s been getting his entire career — based in part on assumptions that Godard means to communicate something but is either too damned perverse or inept to do so. Instead, the guy keeps making making these crazy, confounded, chopped-up, mixed-up, indecipherable movies! Possibly just to torture us.” He offers as evidence quotes from New York Times reviews over the decades.

Eric Kohn gauges the controversy and offers a tentative defense of the film on indieWIRE.

For our reports on various festivals, see the categories on the right. We discuss Godard’s compositions, late and early, here and his cutting here.

Beyond praise 3: Yet more DVD supplements that really tell you something

Darby O’Gill and the Little People (1959)

Kristin here–

Every now and then I discuss a few DVD supplements that teachers might find useful for their classes, though they might be of interest to others as well. Previous installments can be read here and here.

Darby O’Gill and the Little People (Walt Disney Video)

Yes, you read that right. I can’t claim credit for having discovered this disc’s excellent supplement, “Little People, Big Effects.” Shortly after the second “Beyond praise” entry, Dan Reynolds, who teaches at the University of California Santa Barbara, wrote to recommend it.

Darby O’Gill was one of the few Disney live-action films I missed when I was growing up in the 1950s. I acquired the disc and started by watching the feature. I must say that this is one weird movie.

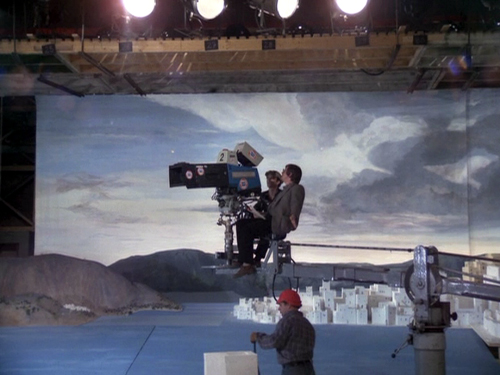

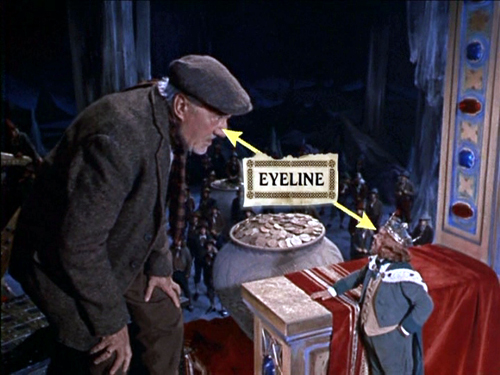

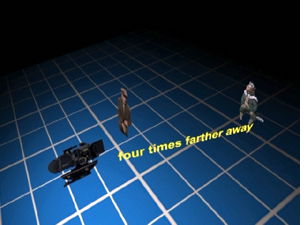

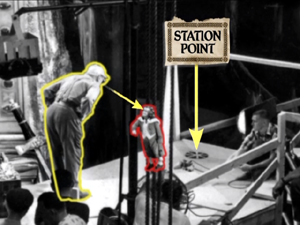

The “little people” of the title are leprechauns, and the special effects used to make them look small are mostly achieved through forced- perspective techniques. In less than eleven minutes, this supplement demonstrates the use of glass paintings, mattes, false perspective, and even a revived Schüfftan process, most famously used for Metropolis, where scale is manipulated by shooting into an angled, partially transparent mirror. Careful calculations allow for over-sized sets in the background to be lined up precisely with normal-scale ones in the foreground, so that the foreground person looks much larger then the background one. Since the two characters, here Darby and King Brian, are supposed to be conversing face-to-face, a manipulation of eyelines, a term we use a lot in Film Art, is necessary. (Despite what my spell-check keeps trying to tell me, “eyeline” is one word in the movie business, as demonstrated above.) In explaining how the actors knew where to look in the shot illustrated at the top, the film shows that “station points” were placed on the floor so that the characters’ eyelines would seem to match up (below). These days actors alone against blue or green screens often have to look at tennis balls to make the direction of their gaze match correctly.)

Clearly some behind-the-scenes footage was made during the production of Darby O’Gill, and this is incorporated into a documentary that includes interviews with master effects expert Peter Ellenshaw, who died in 2007. Ellenshaw worked as a matte painter on half the British classics of the 1930s and 1940s, including Black Narcissus (which has perhaps the greatest matte paintings ever). He then moved to Hollywood in 1950 and began a string of films with Disney that won him an Oscar for Mary Poppins. It’s good to have even these short clips of him demonstrating and discussing his work.

“Little People, Big Effects” should give students (and just about anyone else) a better grasp of perspective and its importance in the representation of depth on a flat screen. I would definitely show it as part of a study of cinematography. If a fifty-year-old film seems a bit out of date, point out to students that, as the narrator mentions, exactly the same techniques were used in many scenes of The Lord of the Rings to make the hobbits and dwarves look small. Similar demonstrations are provided in the supplements to the extended DVD version of The Fellowship of the Ring (Disc 1, “Visual Effects: Scale”).

Elijah Wood sits further from the camera than Ian McKellen in order to make him appear as small as a hobbit

Zodiac (“2-Disc Director’s Cut,” Paramount)

At the end of my first “Beyond praise” entry, I complained about the lack of supplements on the initial DVD release of Zodiac. Then, after the two-disc set with the supplements appeared in early 2008, I forgot to include it in the second entry. Better late than never, so I’m tackling it here. (The supplements are apparently the same for the Blu-ray set.)

As the “DVD Talk” review says. “The self-congratulatory praise is kept to a minimum.”

The main supplement is a 53-minute film called “Deciphering Zodiac.” It’s a good, objective, chronological summary of the film’s production. A lot of talking heads are included, such as the producer, scriptwriter, set decorator. That’s usually a good sign, since it shows that care was taken with the making-of and that enough of the crew members are participating that the account will probably be rounded. There’s a 15-minute making-of specifically on “The Visual Effects of Zodiac.”

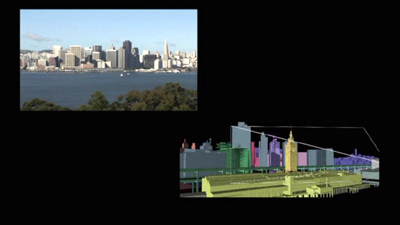

Zodiac was primarily shot on professional-level digital cameras, apart from the slow-motion shots, which still need to be done on 35mm due to limitations of the digital technology. Hence there’s a lot of information here on digital techniques. Most of these techniques are used in ways that aren’t necessarily obvious to the viewer. If you want to show students some material on digital effects, this might be a good choice, since it avoids the flashy, obvious effects that so many fantasy and sci-fi DVD supplements concentrate on.

“Deciphering Zodiac” has shots showing the digital camera attached to an elaborate rig around a car, which was used to follow moving cars, including the famous opening tracking shot along a suburban street. The video-assist monitor is often visible in the shots.

One change that digital filming has made in production has been the frequent use of “digital dailies” rather than dailies on film. (Dailies are the unedited takes just as they come from the camera(s); directors and other key creative people typically watch them at the end of each day.) Several scenes of the “Deciphering” documentary show raw shots and are labeled as digital dailies, something which doesn’t seem to be a common feature of supplements. It’s pretty obvious that the shot of Jake Gyllenhaal below would need to be manipulated in post-production. There’s also informative coverage of the methods used to match location and studio-shot footage, particularly for the scene where the killer shoots a taxi driver.

The visual effects documentary has good explanations of the early shot of a rapid move across the bay toward San Francisco as it looked in the period when the film’s action begins, a shot that was done entirely digitally.

Now that so many best-lists for the decade have included Zodiac, it seems to be an official modern classic. Perhaps a somewhat more dignified way of teaching special effects than using a Transformers movie.

The Dark Knight (Two-Disc Special Edition, Warner Home Video)

The supplements for The Dark Knight make a nice contrast with those for Zodiac. Here the makers of a spectacular action movie avoided digital special effects to a surprising extent. Instead they used practical effects, that is, effects accomplished via physical means while shooting rather than those done in post-production via laboratory or digital manipulation. Digital technology was used, of course, but often for rather modest tasks in planning and in erasure of unwanted elements. It’s also interesting as the first 35mm fiction feature to be shot partially on Imax cameras.

The main supplement is “Gotham Uncovered.” It begins by showing how the Imax camera was initially tested on a single action scene shot on location in Chicago. The results led to additional Imax scenes being added to the film. The advantages of Imax—primarily a huge gain in visual quality due to the larger size of the individual frames—are shown to be balanced against the camera’s limitations. The camera is much larger, making handheld shots difficult. It holds only three minutes of film and has a shallower depth of field. While interesting, this first section is surprisingly lacking in actual footage of the filming, often depending on still photos. We tend to assume that in this day and age, the making-of is taken into account from early on in a production. It’s surprising how often that turns out not to be the case.

A five-minute segment, “The Sound of Anarchy,” shows Hans Zimmer sitting at a computer and talking about the modernist, dissonant music for the Joker character. It’s mildly informative.

“The Chase” is perhaps the most useful section of the making-of. The decision was made to shoot the scene on Lower Wacker in Chicago. Here digital effects were kept to a minimum, with multiple cameras mounted on vehicles like the motorcycle below. These were special smaller Imax cameras. Only four such cameras existed at the time, though an accident reduced that to three!

One big moment in the chase has the Batmobile crashing into a garbage truck. Again, rather than resorting to digital effects, the crew built miniatures of the two vehicles and the set. The decision was also made to shoot a crash of an 18-wheeler on LaSalle Street using a real truck on location, and the scenes showing the practice sessions for this reveal the kind of planning that goes into the big action scenes that are so common in films these days.

A multi-vehicle crash scene was done with several cameras, which is common practice for unrepeatable actions. (Even on a big-budget film like this, no one would want to crash more than one Lamborghini.) The cameras often show up in each other’s shots, and the supplement shows the resulting footage and how CGI is later used to erase them—again, a very common use of digital tools. Here a camera on a crane is visible at the center left in the original footage of the crash:

In one scene, the Joker walks out of a hospital, which explodes behind him. A prime candidate for digital effects, one would think. Instead, the filmmakers opted to have a demolition company destroy a real building. CGI was used to plan the scene:

A shorter supplement, “The Evolution of the Knight,” deals mostly with the design process for Batman’s suit and the Batpod. Again the emphasis is on bringing reality into the filming. It’s pointed out that while much of Batman Returns was shot on sound stages, the team decided to try and shoot the sequel in the city streets as much as possible.

Beware of these

I have to admit, one reason that this series appears so rarely is that for every DVD with useful supplements that I find, there are two or three uninformative ones that I have to sit through–or at least sample. In addition to recommendations, let me warn you away from some of the ones I switched off.

I had expected the Slumdog Millionaire DVD extras to be interesting, given the mixture of digital and 35mm shooting, the location work, and so on. But obviously the filmmakers had no idea that the film would be a success, so they seem to have done little behind-the-scenes shooting as they made it. The result is a not terribly informative, bare-bones 18-minute making-of.

Supplements as praise-fests have not gone away. Musicals seem especially to bring them out. “Get Aboard! The Band Wagon” provides 36 minutes of mutual admiration. In “From Stage to Screen: The History of Chicago,” Chita Rivera unintentionally achieves a parody of the gushing movie star who lauds everyone she worked with.

David and I just watched Cloudy with a Chance of Meatballs. I had liked it when I saw it in first run, and predictably, David enjoyed it, too. It’s a clever, well-scripted, well-animated film. We hoped to learn something from its supplements, but the making-of seems to be aimed at children, and young ones at that. The co-directors and some of the other filmmakers look distinctly embarrassed to be participating, partly because a lame comparison of making a film to mashing food together forms a running motif. A pity, since the movie deserves better. As reviewers keep pointing out, the best animated films these days are made for adults as much as for children.

DER GOLEM: Revisiting a classic

Kristin here:

In 2009, Il Giornate del Cinema Muto, the silent-film festival held each year in Pordenone, Italy, launched a new series. “Il canone rivisitato/The Canon Revisited” addressed the fact that many rare and often obscure silent films are made available through restoration each year, and yet many young enthusiasts who have started attending the festival have seldom had the chance to see the classics on the big screen with musical accompaniment. The opening group of films proved highly successful, and “Il canone rivisitato 2” will be presented this year, when Il Giornate will run October 2 to 9.

Part of the point of the series is to have historians re-evaluate these classics and examine how well they live up to their status as part of the film canon. Last year I contributed a program note on Paul Wegener and Karl Boese’s 1920 German Expressionist film Der Golem. This year I’ve written about Danish director Benjamin Christensen’s 1916 thriller Hævnens Nat (Night of Revenge, released in the U.S. in 1917 as Blind Justice), which will be shown this year, and rightly so.

When I went back and reread my Golem notes to remind myself what sort of coverage is needed, I decided that the text I wrote then might be of wider interest to those who weren’t at the festival last year. Thanks to Paolo Cherchi Usai, one of the festival’s founders and organizers, for permission to revise my brief essay as a blog entry. I’ve changed it minimally and taken the opportunity to add illustrations. Here’s what I said at the time:

Der Golem is a classic film—doubly so.

First, it has long nestled comfortably within the list of titles that make up the German Expressionist movement of the 1920s. Teachers of survey history courses are more likely to show Das Cabinet des Dr. Caligari (which premiered in early 1920) but a serious enthusiast will make it a point to see Der Golem (which appeared later the same year) as well.

From the start, reviewers recognized Der Golem as Expressionist. In 1921 the New York Times’ critic wrote, “Resembling somewhat the curious constructions of THE CABINET OF DR. CALIGARI, the settings may be called expressionistic, but to the common man they are best described as expressive, for it is their eloquence that characterizes them” (George Pratt’s Spellbound in Darkness, p. 362). In 1930, Paul Rotha’s The Film Till Now, the most ambitious world history of cinema in English to date, appeared. Highly influential in establishing the canon of classics, Rotha adored Weimar cinema, including Der Golem.

In 1936, the Museum of Modern Art obtained a large number of notable European films. The core collection of the young archive contained such prestigious titles as Caligari, Battleship Potemkin, Metropolis, and Der Golem. These films soon became part of the museum’s 35mm and 16mm circulating programs. With MOMA’s sanction as historically important classics, they remained the most widely accessible older films available to researchers and students alike for many decades.

There is, however, a second, largely separate audience: monster-movie fans. Starting in the 1950s, German Expressionist films were promoted as horror fare by Forrest J. Ackerman in his magazine Famous Monsters of Filmland. In 1967 Carlos Clarens included Der Golem in his An Illustrated History of the Horror Film. Really dedicated horror devotees pride themselves on their expertise across a wide variety of films, including foreign and silent ones. Der Golem became a certified horror classic.

In the 1950s and 1960s, companies offering public-domain 8mm and 16mm copies for sale enabled both film-studies departments and movie buffs to start their own film libraries. Ultimately home video made previously rare silent classics easily obtainable—including a restored Golem from the Friedrich Wilhelm Murnau-Stiftung, with new tinting and a musical score, on DVD. Such a presentation reconfirms the film’s status as a classic.

But what sort of classic is it? An undying masterpiece that one must see immediately? A film one should definitely watch someday if the chance arises? On the occasion of Der Golem being presented on the big screen with live musical accompaniment, we have a chance to specify what distinguishes it from its fellow exemplars of Expressionism.

I suspect that horror-film fans won’t feel that a reevaluation is necessary. Der Golem is a forerunner of Frankenstein and hence an important early contribution to the genre. It’s a striking film to look at and obscure enough to impress one’s friends during a late-night program in the home theater.

But for film historians returning to Der Golem in the early twenty-first century, after nearly ninety years of taking it for granted, what is there to say?

Some would deny that Der Golem is truly Expressionistic. If one has a very narrow view of the style, insisting that only films with flat, jagged, Caligari-style sets qualify for membership in the movement, then Der Golem doesn’t pass muster. Neither do Nosferatu, Die Nibelungen, Waxworks, and a lot of other films typically put into the Expressionist category.

Some would deny that Der Golem is truly Expressionistic. If one has a very narrow view of the style, insisting that only films with flat, jagged, Caligari-style sets qualify for membership in the movement, then Der Golem doesn’t pass muster. Neither do Nosferatu, Die Nibelungen, Waxworks, and a lot of other films typically put into the Expressionist category.

It’s a subject susceptible to endless debate. To avoid that, it’s helpful to accept historian Jean Mitry’s simple, useful distinction between graphic expressionism, with flat, jagged sets, and plastic expressionism, with a more volumetric, architectural stylization. If Caligari introduced us to graphic Expressionism in 1920, Der Golem did the same for plastic Expressionism later that year.

For me, seeing Der Golem again doesn’t much affect its status as an historically important component of the German Expressionist movement. It’s not the most likeable or entertaining of the group. Caligari has more suspense and daring and black humor. Die Nibelungen has a stately blend of ornamental richness with a modernist austerity of overall composition, as well as a narrative that sinks gradually into nihilism in a peculiarly Weimarian way.

Moreover, Der Golem’s narrative has its problems. None of the characters is particularly sympathetic. Petty deceits and jealousies ultimately are what allow the Golem to run amok. The narrative momentum built up in the first half of  the film is inexplicably vitiated for a stretch. Initially the emperor’s threat to expel Prague’s Jews from the ghetto drives Rabbi Löw to his dangerous scheme of creating the Golem to save his people. Yet after the creation scene, the dramatic highpoint that ends the first half, we see the magically animated statue chopping wood and performing other household tasks that make his presence seem almost inconsequential. The imperial threat has to be revved up again to get the Golem-as-savior plot going again.

the film is inexplicably vitiated for a stretch. Initially the emperor’s threat to expel Prague’s Jews from the ghetto drives Rabbi Löw to his dangerous scheme of creating the Golem to save his people. Yet after the creation scene, the dramatic highpoint that ends the first half, we see the magically animated statue chopping wood and performing other household tasks that make his presence seem almost inconsequential. The imperial threat has to be revved up again to get the Golem-as-savior plot going again.

But putting aside Der Golem’s minor weaknesses, it has marvelous moments that summon up what cinematic Expressionism could be: the opening shot, which instantly signals the film’s style (below); the black, jagged hinges that meander crazily across the door of the room where Löw sculpts the Golem; the juxtaposition of the Golem with a Christian statue as he stomps across the crooked little bridge returning from the palace (at top).

Hans Poelzig was perhaps the greatest architect to design Expressionist film sets. He designed only three films, and Der  Golem is the most important of them. Once the monster has been created, Poelzig visually equates the lumpy, writhing towers and walls of the ghetto and the clay from which the Golem is fashioned. The sense that sets and actors’ performances constitute a formal, even material whole became one of the basic tactics of Expressionism in cinema.

Golem is the most important of them. Once the monster has been created, Poelzig visually equates the lumpy, writhing towers and walls of the ghetto and the clay from which the Golem is fashioned. The sense that sets and actors’ performances constitute a formal, even material whole became one of the basic tactics of Expressionism in cinema.

Speaking of performances: A lot of the actors in German Expressionist films were movie or stage stars who didn’t specialize in Expressionism. There were, however, occasional roles that preserve the techniques the great actors of the Expressionist theater. There’s Fritz Kortner in Hintertreppe and Schatten. There’s Ernst Deutsch, who acted in only two Expressionist films, as the protagonist in the stylistically radical Von morgens bis Mitternacht (out this month on DVD) and as the rabbi’s assistant in Der Golem.

Just watching his eyes and brows during his scenes in this film conveys something of the experimental edge that Expressionism had when it was fresh—before its films had become canonized classics.

Watching a movie, page by page

The Ghost Writer (above); The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo (below).

DB here:

Aristotle said, quite reasonably, that every plot has a beginning, a middle, and an end. But that doesn’t mean that every plot consists of three acts. Aristotle doesn’t mention act divisions in the Poetics for the good reason that classical Greek plays didn’t have them. The three-act play is just one convention that emerged in the history of storytelling.

As early as 20 BCE Horace was suggesting, “Let no play be either shorter or longer than five acts.” Influenced by this edict, Renaissance editors and playwrights adhered to five acts for many years. We have, of course, plays in two acts (Alan Ayckbourn’s Norman Conquest cycle) and four acts (Pygmalion, The Admirable Crichton, many of Chekhov’s). TV dramas are routinely divided into a teaser and four acts, broken up by commercials. All of those plots have beginnings, middles, and ends, so it’s silly to think that only the three-act structure can fulfill Aristotle’s dictum.

As early as the seventeenth century, the Spanish playwright Lope de Vega recommended three acts as best. In Europe, the format came into its own during the nineteenth century, evidently dislodging the five-act one. One reason may have been that three parts are architecturally simple, sturdy, and easily visualized. Around 1820 Hegel remarked: “Three such acts for every kind of drama is the number that will adapt itself most readily to intelligible theory.” What such a theory might look like was sketched by Lope, who anticipates modern advice manuals.

In the first act set forth the case. In the second weave together the events, in such wise that until the middle of the third act one may hardly guess the outcome. Always trick expectancy.

So proponents of the three-act screenplay formula should revise their pedigree. They’re actually pushing the Lope-Hegel tradition—which admittedly sounds less impressive than dropping the name of Aristotle.

Three acts, more or less

Despite the historical misunderstandings, there’s some reason to think that Hollywood screenwriters, and now filmmakers across the world, have followed a rough three-“act” scheme. Where they got this idea and when it started is still hard to say, but it’s been at the core of nearly every screenplay manual since the 1980s. Kristin and I have looked at this format from an academic perspective, and our views are outlined briefly on this site here and here and here. For more detailed arguments you can read her Storytelling in the New Hollywood and Storytelling in Film and Television and my The Way Hollywood Tells It.

In those places we’ve argued that Hollywood feature films tend to fall into chunks of 20-30 minutes. As a result a movie may display three parts, or four, or more (if the film is very long) or even two (if it’s unusually short). When the film has four parts, it tends to split the long second act that the manuals recommend into two.

A four-parter usually goes like this. A Setup lays down the circumstances and establishes the primary characters’ goals. The Complicating Action is a sort of counter-setup, modifying the original goals or creating new ones. At about the midpoint, there emerges a Development section characterized by delays, subplots, and backstory. There follows the Climax, which resolves the action by decisively achieving or failing to achieve the protagonist’s goals. The film typically ends with a brief Epilogue that establishes a settled state, happy or unhappy. Each of these sections is demarcated by a turning point—a moment of crisis, usually involving an unforeseen twist or a major decision by the protagonist.

Two recent films, The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo and The Ghost Writer, offer good examples of how the four-part template governs plot structure. I won’t walk through each one here, but both seem to me to adhere quite closely to this model. Today I’m more curious about the original novels. We know that books are routinely reshaped for movie treatment. Is there a sense in which the plot structure of the originals fits the film formula?

Fiction as film

I ask because some fiction writers have come to believe in the enduring power of the three-act structure for all narratives. In The Weekend Novelist (1994), Robert J. Ray recommends that aspiring writers use it (although he breaks Act II into two parts around the midpoint). He finds the pattern enacted in his book’s primary model, the novel The Accidental Tourist. “We’re working with the structure of [Anne] Tyler’s Tourist because it is classical, three acts” (142). This, Ray claims, follows “Aristotle’s dictum of beginning, middle, and end” (141). Ray makes a comparable suggestion in The Weekend Novelist Writes a Mystery (1998), naming the three parts Setup, Complication, and Resolution; a midpoint again splits “Act II.1” from “Act II.2.”

Ray’s are the earliest instances I’ve found of explicitly applying screenwriting structure to prose fiction. Later ones would include Stephen Greenleaf’s 1996 article “A Mystery in Three Acts” and James Scott Bell’s 2004 book Plot and Structure. Bell argues somewhat grimly that life itself has three acts: childhood, “the middle where we spend most of our time,” and “a last act that wraps everything up” (23). Ridley Pearson, in the 2007 article “Getting Your Act(s) Together,” tells us that the “three-act structure, handed down to us from the ancient Greeks [!], is one that’s proven successful for thousands of years” (67). “Name a film or book you think rises above others, and chances are, if you go back and study it, the story line will fit into this form” (85). Brenda Janowitz recommends plotting a Harlequin romance as if it were a movie like Mean Girls.

But screenwriting adepts will notice one thing that these advisors neglect: the lengths of the parts. The book that popularized the three-act structure in film circles was Syd Field’s Screenplay of 1979. Not only did he lay out the template, but he indicated running times for each section. Act 1 should last about thirty minutes, Act 2 sixty minutes, and act three about thirty. Assuming that one minute of screen time equals a page of the screenplay, that means that a two-hour movie should run about 120 pages. Field’s metric proved very influential, with script readers, producers, and writers all striving to find plot points at twenty-five minutes and ninety minutes.

To be strictly parallel, then, a “three-act novel” should be divisible into parts having a page ratio of 1:2:1. The only manual I know that is willing to bite this bullet is Writing Fiction for Dummies (2009). (The title has a catchy ambiguity, no?) According to the authors, Act 1 takes up the first quarter of the book, Act 2 the middle half, and Act 3 the last quarter (p. 147).

In the film versions of The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo and The Ghost Writer, the segments and timings fit the four-part model fairly neatly. (Try it yourself, in the theatre or when the films come out on DVD.) But what happens when we look at published books? Will we find what Ray found in The Accidental Tourist—conformity to the formula? Are practicing novelists using the template? Are the timings, or rather the page-counts, of the books congruent with the film model?

First I’ll consider Robert Harris’ novel The Ghost, the source of The Ghost Writer. The next section looks at Stieg Larsson’s The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo. If you want to avoid spoilers, skim and skip accordingly.

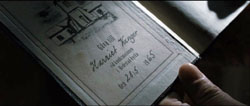

Ghost writers in the sky

The opening chapters of The Ghost introduce the unnamed narrator, a professional writer who is on the verge of breaking up with his girlfriend. Hired to ghost-write ex-Prime Minister Adam Lang’s memoirs, he is replacing Lang’s aide McAra, who drowned under mysterious circumstances. The Ghost takes the job just as news media are floating the charge that Lang helped the US ship British citizens to black sites to be tortured. The Ghost travels to join Lang, who is staying in America with his secretary Amelia and his wife Ruth. At his hotel, the Ghost encounters a surly British man who asks him pointed questions about Lang. This setup lays out the affair between Amelia and Lang, Ruth’s sexual jealousy, and the mounting political pressure on Lang, along with the sinister Brit in the bar. The section ends on p. 83 of the 335-page Gallery paperback edition, almost exactly one-quarter of the book.

The complicating action arrives when the Ghost’s first sit-down with Lang the next day is interrupted by the announcement that Rycart, former Foreign Secretary in Lang’s government, has asked the Hague to investigate the PM for war crimes. Under pressure from protestors, Lang decides to go to Washington for appearances’ sake. In the meantime, the Ghost discovers a set of clues McAra has left behind: photos of Adam in his Cambridge days, records and news reports of his party activities, and a mysterious phone number that turns out to be Rycart’s. All this creates a counter-setup. There is something foul afoot.

The Ghost ruminates constantly on McAra, a writer who has become something of a ghost haunting his successor. Soon the digital file of McAra’s draft of the memoir vanishes from the Ghost’s email. Most fundamentally, he discovers that in the first interview Lang has lied to him about how he got into politics.

That was when I realized I had a fundamental problem with our former prime minister. He was not a psychologically credible character. In the flesh, or on the screen, playing the part of a statesman, he seemed to have a strong personality. But somehow, when one sat down to think about him, he vanished. This made it impossible for me to do my job. . . . I simply couldn’t make him up (162).

At this point the protagonist decides on a new goal: to investigate on his own. This transforms his official assignment, and it happens on p. 163—quite close to the midpont of the book.

The development section is filled out with the usual delays, false leads, counter-maneuvers, and backstory. The Ghost’s investigation brings him to an interrogation of an old man who suspects foul play in McAra’s death, a sexual encounter with Ruth, a meeting with a professor with apparent CIA connections, and a suspicious vehicle in the vicinity. The turning point comes with another decision. “The more I considered it, the more obvious it seemed that there was only one course of action open to me.” The Ghost phones Rycart and flies to New York to meet him. This passage concludes on p. 256.

The climax sporadically unravels the clues McAra has left behind. In their meeting Rycart and the Ghost conclude that Lang was recruited by Professor Emmett during their Cambridge days and became a US puppet. Rycart has taped his exchange with the Ghost and uses that to force him to return to confront Lang. On Lang’s private plane, the Ghost accuses him but Lang’s denials are disconcertingly sincere. On disembarking, he is killed by a suicide bomber—the crusty Brit who blames Lang for the death of his son in Iraq. Although he’s haunted by dreams of a drowning McAra (“You go on without me. . .”), the Ghost plows ahead with Lang’s now-posthumous memoirs. All seems to have been settled until the book launch, when the Ghost discovers another way to interpret the evidence. He returns home to check McAra’s manuscript, where he finds a coded message identifying Ruth as the one recruited by Emmett; she was the mole. This revelation that the first solution was wrong, a detective-story device going back at least to Trent’s Last Case of 1913, arrives on p. 330.

An epilogue of only five pages reports that the Ghost is on the run. If anything happens to him, his former girlfriend will publish his story. “Am I supposed to be pleased that you are reading this, or not? Pleased, of course, to speak at last in my own voice. Disappointed, obviously, that it probably means I’m dead.”

The result conforms fairly strongly to the triple ratio: Act 1 runs 83 pages, Act 2 runs 173 pages, Act 3 runs 79 pages. Using the four-part template, we get 83/80/93/74, with a five-page epilogue.

Not perfect symmetry, but that’s hardly to be expected. Novelists stretch or compress as needed, and they can make scene boundaries a little fuzzier than what we find in films. For such reasons, other analysts might shift my breakpoints a few pages fore or aft. In addition, many films make the climax section somewhat shorter than the others, so we won’t always get perfect symmetry in novels either. Still, The Ghost offers a reasonably close approximation to the sort of plot template that we find in many commercial movies.

Double duty

Stieg Larsson’s The Girl Who Played with Fire provides a somewhat different sort of plot. We have two protagonists and three lines of action—two mysteries plus a search for revenge—or rather four, if you count the prospect of a romance between the protagonists. The book is also much longer than The Ghost, running 644 pages in the Vintage paperback edition I have. You might therefore expect more large-scale parts. But . . . .

The setup lays out the three major lines of action. Journalist Mikael Blomkvist, misled by an informant, publishes a false news story about the dealings of the businessman Wennerström. After Blomkvist is sentenced to prison, the second line of action kicks in: Henrik Vanger asks him to find what happened to his brother’s granddaughter Harriet. Meanwhile the neopunk hacker Lisbeth Salander is introduced as a security analyst researching Blomkvist for Vanger. By p. 138 Blomkvist has decided to accept the Vanger assignment. This section is not far from being a quarter of the text, and it corresponds to a major break, the end of Part 1 (“Incentive”).

The next large-scale section complicates things on two levels. It plunges Blomkvist into the details of Vanger family history and Harriet’s disappearance, and it brings Lisbeth Salander’s life to a point of crisis. We learn her past as an orphan and a denizen of the streets and hacker subculture, living under the thumb of her guardian Bjurman. This section is rather long, about 150 pages, because it has to establish Lisbeth as a dual protagonist and show her stratagems for escaping Bjurman’s sexual exploitation. Blomkvist must also serve his short prison time in this segment.

I’d argue that the plot’s midpoint occurs on page 323, halfway through the book. Chapter 16 begins:

After six months of fruitless cogitation, the case of Harriet Vanger cracked open. In the first week of June, Blomkvist uncovered three totally new pieces of the puzzle. Two of them he found himself. The third he had help with.

These revelations propel Blomkvist into a lengthy investigation of serial murders, which requires him to hire Lisbeth as his research assistant. While the two follow up clues, they start an affair.

On p. 477, it seems to me, the climax begins. The investigation has cast suspicion on Martin Vanger, Harriet’s brother. Blomkvist hears Martin returning home. “That somehow brought matters to a head.” Blomkvist goes out to confront him. Two pages later Martin shows him into the basement. “Blomkvist had opened the door to hell.” Now scenes of Lisbeth’s research and return to the village alternate with scenes showing Blomkvist at the mercy of Martin in his torture chamber.

Because the central plot involves two mysteries, the climax is extended. I’d argue that the two mysteries, the serial killings and Harriet’s disappearance, are solved by page 560 or so. But there remains the matter of Blomkvist’s revenge on the plutocrat Wennerström, who had tricked him into printing a phony story.

That dangling plotline is tied up in the next chunk (pp. 562-628), which forms in effect a second climax. Thanks to Lisbeth’s research, Blomkvist and his partners prepare to publish an expose of Wennerström’s crimes in Millennium. The evening that Blomkvist goes on TV, public opinion shifts decisively in his favor, and as the translation has it, “Blomkvist’s appearance marked a turning point.” He has won, and so has Lisbeth, who has drained money from Wennerström’s offshore accounts.

The sixteen-page epilogue tells us that Wennerström, facing disgrace and jail, kills himself. By now the two protagonists have struggled up from below. Blomkvist redeems his reputation and becomes the toast of journalism. Lisbeth, poor and victimized by men, becomes independent and enjoys her stolen fortune. There remains only the question: Will the two unite romantically? A final scene replies with a very old plot devices that’s one of Larsson’s favorites: a chance encounter that triggers a misunderstanding.

So I’m proposing a 138-page setup, a 150-page Complicating Action, and a 154-page Development. If you consider my two climaxes a single stretch, you have a 149-page climax section. That makes the big parts roughly equal, with a tailpiece of 16 pages. Even though The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo has nearly twice the page-count of The Ghost and crams in two protagonists and several plotlines, it displays the symmetry we find in the more compact book. The chief difference is between a comparatively short climax and a protracted one—the same difference we often find in classically constructed films. For these novels, and I suspect many others, the three-act/ four-part template provides a solid architecture for the plot.

Miracles, critical fantasies, or just tradition?

I won’t try to align the parts articulated in the novels with those we find in the finished films. The congruences are fairly close, once you grant that both films compress scenes and lop off characters and plotlines that are developed in the novels. Instead, I want to close by asking some questions.

Would novelists admit to consciously adopting this structure? If they don’t, or if we think it’s implausible that they would, we’re confronted with the charge that we’re simply projecting this structure onto the books. Are we and the writers of manuals shoehorning these plots into the three-act/ four-part format? Could we come up with equally persuasive patterns if we set out looking for seven or seventeen or seventy “acts”?

To take the last question first: Probably not. I think my analyses carve the films and books at the joints, more or less. One reason I like Kristin’s analytical method is that it hinges on characters’ goals and their pivotal decisions or reactions. These tend to be emphatic, well-articulated moments in the plot; a lot, as we say, depends on them.

True, there is some room to argue about which ones might be most far-reaching. You can propose alternatives, and I can change my mind. But the rival candidates for goals and decisions and major turning points aren’t likely to be radically different. We agree on most structural conventions, and our differences tend to be fine-grained, not gross.

Still, this sort of analysis arouses skepticism, and rightly so. How can writers and filmmakers achieve this neat structure without conscious planning? Can you follow the rules without doing so deliberately? Kristin offers an explanation that emphasizes the intuitive search for proportion in the creative process. She invokes Vivaldi concerti, medieval altarpieces, daily comic strips, and even the Great Pyramid at Giza as examples of balance among parts in both high and popular arts.

The evident use of proportions in many narrative films provides one more indication of the enduring classicism of the mainstream Hollywood system. Presumably what practitioners have intuitively assumed to be the optimum range of lengths for each part was discovered early on. It has been passed down the generations of filmmakers as a result of the simple fact that most practitioners gain their basic skills by watching a great number of movies (Storytelling in the New Hollywood, 44).

I think that there’s still a lot to learn about these templates. How are they disseminated among filmmakers? Why are we unaware of these parts while watching the film? They don’t stand out like chapter divisions in a novel. Or do we sense them subliminally? And how widespread are they? Do we find them in classic studio cinema of the 1920s through the 1950s? (Kristin thinks so, as do most writers of screenplay manuals.) Do we find them in films from other cultures and periods? If so, perhaps filmmakers elsewhere have found them to be reliable ways to engage viewers. Possibly these models were spread with the circulation of American movies.

I’ll provide my own epilogue by noting that the novelists’ borrowing of screenplay structures is a recent instance of a long-term process: the “cinefication” of other media. Today we call successful novels “tentpoles” or “blockbusters” or “locomotives,” and we say they’re “released” rather than “published.” What used to be called a series of novels is now likely to be called a franchise. It may be that many novelists have absorbed the lessons of screenplay manuals. If you wanted your book to be bought by a producer, why not make it like a film beforehand?

More abstractly, we have artistic transfer and technical influence. For a long time critics have argued that literary modernists like Faulkner and Hemingway, along with more popular genre writers, have tried for “cinematic” styles and have sought to imitate the “camera eye” in their narration. Today perhaps we see a structural influence as well: rules of film plotting mapped onto prose fiction. The next page-turner you read may have been engineered to flow across your eyes at the brisk pace of a Hollywood movie.

Several of my references to classical theorizing about act divisions are taken from Oscar Lee Brownstein and Darlene M. Daubert, eds., Analytical Sourcebook of Concepts in Dramatic Theory (Westport, CT: Greenwood, 1981). For more on classical Greek drama’s structure, go here. You can read a brief summary of the history of act divisions in western drama here.

On the three-act screenplay structure as applied to independent films, see J. J. Murphy’s You and Me and Memento and Fargo. See also J. J.’s independent cinema blog.

Stephen Greenleaf’s “A Mystery in Three Acts” appeared in The Writer 109, 4 (April 1996). Ridley Pearson’s article “Getting Your Act(s) Together” appeared in Writer’s Digest 87, 2 (April 2007), 67-69, 85. For another application of three-act structure to the novel, go here. The author claims that “movies rather than books are easier to analyze in that the main plot points are visual.”

On The Ghost Writer, a useful interview with Robert Harris is here. An entry on Creative Loafing points out ambiguities and vague spots in the movie’s plot. A January 2008 draft of the script, which incorporates voice-over narration, is available here.

The most influential account of how American novelists adapted cinematic techniques is Claude-Edmonde Magny’s Age of the American Novel: The Film Aesthetic of Fiction between the Two Wars. See also Keith Cohen’s Film and Fiction: The Dynamics of Exchange.

The Ghost Writer.