A serial for the unserious

Wednesday | July 14, 2010 open printable version

open printable version

Please silence your mobile phone during the film! Le Pied qui étreint 1: Le Micro bafouilleur sans fil (1916).

DB here, still in Yurrp:

Today the Cinémathèque Française will celebrate Bastille Day by showing one of the strangest movies the programmers could have picked–sort of the Monty Python’s Flying Circus of the 1910s.

Le Pied qui étreint (1916), directed by Jacques Feyder, is a four-part parody of the crime serial. The title translates as “The Clutching Foot,” and as if that weren’t a clear enough signal, Gaumont’s announcement in the trade press set the tone:

A sensational film in 1979 episodes–assembled in four installments without any dull spots.

The running conflict pits the plus-size inventor Clarin, his boy assistant, and his rich girlfriend Eliane against a ruthless, incompetent secret society modeled on Feuillade’s Vampires. The boss of the gang is a mysterious masked figure always wheeled around in a baby carriage with his feet sticking out in front. Gang members recognize each other by flashing an emblem of a bare foot painted on the soles of their shoes.

In the first episode, Clarin invents a wireless telephone, which causes him some embarrassment in movie theatres. Electricity is also on the mind of the Clutching Foot gang, who rewire Eliane’s house so that when she answers the phone she falls into spasms of shocks. Soon all the servants who try to grab her are splayed out on the floor, convulsing in synchronization. Fortunately Clarin and his assistant rescue all by judicious use of rubber gloves.

In “The Black Ray,” the gang devises a gadget that emits a beam that will turn a white person black. The device proves startlingly effective on Eliane, but again Clarin has a scientific solution, sending a current through her to revive her pale beauty. Part three involves the Chinese branch of the The Clutching Foot. They kidnap Eliane and lull her into languor by means of a sinister incense. But Clarin, disguised as a Chinese, rescues her, and his boy displays unexpected pistol skills by dispatching a dozen Chinese while eating a bun.

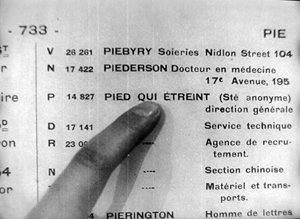

Feyder and his scriptwriters make merciless fun of the still-emerging serial conventions. Masked thugs break into a house, but passing citizens and policemen are completely indifferent. A mysterious message is sent to the heroine via paper airplane, which gets stuck in her hair. When some of the gang converge on Eliane’s parlor, they hide in different crannies and flash their foot-insignia all at once. The apparently unlimited resources of Zigomar and Fantomas are taken to their logical conclusion when the Clutching Foot team boasts of its resources in the city directory.

The iconic image of cops converging on crooks is pushed to a nutty limit.

The last installment is the most peculiar. The master of the Clutching Foot is revealed to be none other than Charlie Chaplin. This shameless effort to cash in on the star’s popularity makes him central to the episode. After a chase through a hotel, Chaplin escapes the cops, worms his way into Eliane’s affections, and winds up marrying her. The wedding feast features a lookalike for the star Max Linder as well as guests from other Gaumont films, including the child star Bout-de-Zan and Marcel Levèsque, a comic fixture in early Feuillade and memorable as the censorious concierge in Le Crime de Mr. Lange. The Charlot imitator is Georges Biscot, discovered by Feyder and soon to play many roles for Feuillade. The woman who slinks around in her leotard and makes with those Irma Vep eyes is Musidora herself. The jokey star walk-on is clearly not unique to our time.

The movie ventures into new territory at the end, when Charlot and Eliane retire to the bridal suite. For once the randy tramp gets some real action.

In a nice closing touch, the hotel staffer who collects shoes for cleaning writes the room number in chalk on Charlie’s boots–a recollection of the high-sign of his gang.

I haven’t mentioned other appeals, such as Chinese gangsters flung off a spinning weather vane, or the moment in the last installment when Clarin’s lad sets up a projector in the lab and, as if willing the whole movie to start over, screens the opening of the serial’s first part. Take that, Postmodernism!

It’s all a bit juvenile, but no harm in that. Sometimes, as Tsui Hark remarks, it’s fun to be stupid. And Le Pied qui étreint should remind us of something important. Too often we assume that parody is a sign that a form or genre is exhausted, that there’s nothing left to do but mock it. But that’s not always so. Parody needn’t announce decline or decadence. Parody is lurking everywhere, ready to spring out as soon as conventions are crystallizing. Irreverence, vulgarity, reflexivity, derangement, and dirty fun are wired into popular cinema from the very start.

For contemporary reactions to the film, which were a little stiff-lipped, see Henri Bousquet, “‘Le pied qui étreint,'” Cahiers de la Cinémathèque no. 40 (1984), 23-24. My quotation from the Gaumont ad is taken from this article. For a brief online comment and a nice production still, go here.

Thanks to Nicola, Francis, and Bruno, who reminded me that Feyder was a Belgian.

Marcel Levèsque, Kitty Hott, Biscot, and Musidora at the wedding feast.