No coincidence, no story

Thursday | August 26, 2010 open printable version

open printable version

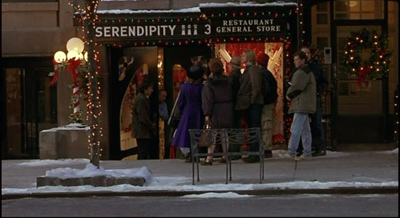

Serendipity.

DB here:

I’ve been thinking about coincidences lately. Watching Hong Kong movies can do that to you.

Hong Kong vs. Hollywood?

Initial D; I Corrupt All Cops.

In Initial D (2005, Andrew Lau Wai-keung and Alan Mak Siu-fai, script by Felix Chong Man-keung), the protagonist Takumi is dazedly in love with the seductive schoolgirl Natsuki. Takumi’s pal Itsuki is out with another girl when he spots Natsuki riding out of a “love hotel” with an older man. Itsuki tells his pal. This leads to a major crisis, in which Takumi’s faith in Natsuki is shaken.

Then there’s I Corrupt All Cops (2009) from the indefatigable writer-director-producer-actor Wong Jing. (Many wish he were far more fatigable.) Unicorn, a corrupt, brutal police officer, has just been savagely beaten by gamblers who once were his allies. He staggers to a street stall and nearly collapses, spitting blood into his congee. Then he glimpses his girlfriend getting out of a rich man’s car. In the next scene, when he visits her apartment, he finds his boss, the even more corrupt cop Lak, in her bed. His realization that he can trust no one pushes him to join the police anti-corruption unit.

True, the coincidences play different roles in the two movies. In Initial D, there might be an innocent explanation for Natsuki’s visit to the hotel. Perhaps Takumi’s friend even mistook another girl for her. So we may be inclined to suspend our judgment and wait for more information about whether she’s actually being unfaithful. In I Corrupt All Cops, Unicorn’s suspicions about his girlfriend’s disloyalty are immediately confirmed; instead of suspense, we get surprise, in the form of the revelation of who her lover is.

But in each case, a major plot movement is triggered by sheer accident. Itsuki wasn’t spying on Natsugi’s assignation; he was trying to talk his date into the love hotel. Unicorn wasn’t suspicious of his girlfriend, he just happened to be across the street when she came home. Each coincidence is also a matter of timing: Had either man come a few minutes later to the location, he wouldn’t have learned the big secret. In retrospect, we are likely to think that the screenplays of Inital D and I Corrupt All Cops are using chance rather than causality to move their action forward.

Granted, Hong Kong films are generally weak in plot construction. Even the lauded films of Wong Kar-wai are built out of casual encounters and unpredictable turns of events. The old Chinese maxim “No coincidence, no story” might seem to give accidental revelations a high place in this cinema. But Hong Kong films aren’t outstanding offenders. When you start to look, you find that films in different traditions are no less committed to coincidence. After all, Rick in Casablanca notices the vast implausibility of what’s just happened: “Of all the gin joints in all the towns in all the world, she walks into mine.”

One precept of Hollywood screenwriting has been that coincidences are permissible when you’re setting up the narrative. Indeed, they’re often necessary: Circumstances have to come together in some way to launch an extended action. A sudden rainstom brings boy and girl together under the same awning, creating the cute meet, and things can build from there.

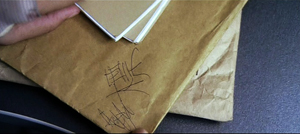

But, the Hollywood wisdom goes, don’t use a coincidence to develop or resolve the plot. Consider another Hong Kong film, Infernal Affairs (2006, directed by Lau and Mak, with script by Chong). Chan the undercover cop has come in from the cold. While officer Lau is out of his office, Chan is poking idly around Lau’s desk. There he finds the envelope on which Chan himself once scribbled a correction.

That envelope was in the hands of the gang that Chan joined. If Lau has that envelope, he must be the triad mole in the police force. This recognition triggers the film’s climax: Chan flees police headquarters and sets out to unmask Lau’s treachery.

You would think that if Hollywood filmmakers were anxious to avoid such a timely accident, the Infernal Affairs remake known as The Departed (directed by Martin Scorsese, script by William Monahan) would find another way for Billy Costigan to discover that Colin Sullivan is the mole. But no. Billy notices the telltale envelope sticking out from a pile of papers on Sullivan’s desk.

The different ways the two films drive the discovery home to the audience merit a closer look than I can spare here. My point is that the handy coincidence of the police mole leaving this damning clue for his adversary to find is used without apology in the Hollywood movie. And like its counterpart, the scene sets off the movie’s climax. You could even argue that Infernal Affairs supports its revelation a little better. Billy accidentally glimpses the crucial envelope, but Chan is actively browsing Lau’s desk, perhaps because after years spent among triads he doesn’t trust anyone .

So you have to wonder. Maybe filmmakers in many traditions have accepted the Chinese maxim. Moreover, contrivance of this sort doesn’t seem to damage a film’s reputation. (Many critics considered The Departed one of the very best US films of 2006.) More generally, we seldom feel such coincidences to be arbitrary or forced. Maybe screenwriters and directors have found ways to mask the coincidental tenor of such scenes.

As with our earlier Inception entry, we’re in the realm of motivation.

The roots of coincidence

Most story actions result from characters’ choices, purposes, reactions, plans, and the like. These factors create patterns of cause and effect. Chan/Billy didn’t just mosey into Lau/ Colin’s office: He came in because he thought it was safe to break his cover. We accordingly worry for him because we know, as he doesn’t, that he’s far from safe.

Everyone seems agreed that a plot can’t replace all causal connections with a string of coincidences. If everything happens by convenient accident, then we can’t form any expectations about what will happen next. And without expectations, our cognitive and emotional engagement with the story is likely to be slight. Moreover, designing a story packed with coincidences isn’t that hard. Children do it all the time. But most artistic traditions thrive on their constraints. If anything at all can happen to advance or conclude your plot, you’re playing tennis without a net. The interesting challenge for a storyteller in traditional forms is to create a pattern of incidents that arouses our curiosity, builds up suspense, and presents surprises that turn out to be, in retrospect, cunningly prepared for—all the while playing on our emotions.

Yet, and again: No coincidence, no story. Sometimes, the plot’s forward momentum needs encounters and discoveries not planned by the characters. So how can these convenient accidents be made to serve narrative craft?

Well, what is a coincidence anyway? At the least, it’s a matter of converging incidents, as the name implies; but surely it involves more.

I wake up one morning and ask, “I wonder what my sisters are up to? I haven’t heard from them in a while.” Nothing important is happening in the family, no health crises or upcoming reunions. I just wonder how the girls are. So I reach for the phone, but before I can dial I get a call from Diane (the Texas sister). I say, “What a coincidence! I was just going to call you.”

This sort of thing happens. But not all the time. Not even most of the time. The thousands of things that flit through our day almost never match up so nicely. And we don’t notice it when they don’t match up, because we don’t expect them to. The non-coincidences of everyday life go unregistered because they’re so pervasive.

On those rare occasions when things do sync up, we notice. In The Evolution of God, Robert Wright puts it well:

It makes sense that human brains would naturally seize on strange, surprising things, since the predictable things have already been absorbed into the expectations that guide them through the world; news of the strange and surprising may signal that some amendment of our expectations is warranted.

We usually attribute such coincidences to chance. But humans aren’t very good at thinking about chance. If the coincidence seems meaningful, as many do, we’re always tempted to consider it the result of some secret force. Did I send out invisible thought-waves that Diane somehow picked up? Did fate, or God, make her call me? In general, when we notice patterns, we look for causes. The phone-call convergence is a pretty minimal pattern, but even there we might be tempted to find a cause.

I hang up on Diane and the phone rings immediately. It’s Darlene (the peripatetic sister). “I was just trying to call you, David, but the line was busy.” This is getting weird. The pattern heightens and may prompt a stronger impulse to search for causes. Do we three siblings mind-meld in some mysterious fashion? (If so, though, why do we need phones?) It’s just a coincidence, highly improbable but, out of all the times we three think about one another and make phone calls, not impossible.

I believe that narrative artists in all media are practical psychologists. They trigger and exploit and heighten our ordinary ways of making sense of the world. Philosophers and statisticians have sophisticated ways of thinking about chance, but they needed special training to get beyond our folk psychology. Artists take us as we are.

Stories can use coincidences because we accept them. They are the sorts of things that sometimes happen, and so, as Aristotle argued, they are fit subjects for plot-making.

The poet’s task is to speak not of events which have occurred, but of the kind of events which could occur, and are possible by the standards of probability or necessity (Poetics, Chapter 9).

Here Aristotle points to two sorts of possible events. There are events that we expect to happen as a necessary result of earlier events; this corresponds to some notion of causality. Then there are events that are merely probable—things that are likely to happen.

But how likely is my call from Diane and the followup from Darlene? Aren’t these examples of what Aristotle dismisses as “the arbitrary and fortuitous”? Not necessarily, because for Aristotle too the storyteller is a practical psychologist. Things that seem unlikely, he says, can be motivated by reference to people’s beliefs or to the fact that improbable things are likely to happen occasionally.

Irrationalities should be referred to “what people say,” or shown not to be irrational (since it is likely that some things should occur contrary to likelihood) (Poetics, Chapter 25).

In sum, how do you motivate a coincidence? Aristotle recommends two tactics, which I could use if I were writing a story featuring the felicitous phone calls. People say that members of a family have a special affinity that can cross time and space. And anyhow, stranger things have happened.

Narrative norms

SPL.

Aristotle suggests a third motivational tactic as well. He says that unlikely things may be resolved “by reference to the requirements of poetry.” Poetry here refers to any verbal artform, just as poet refers to the maker of literary works in general. So what are the “requirements” of storytelling?

Most minimally, a plot needs an inciting incident. If I were a fictional character, my lucky phone calls might kick off a plot in which my sisters and I, feeling a new and mysterious bond, set out on road trips to meet somewhere. The telephone contrivance would correspond to the Hollywood dictum that coincidences are permissible at the outset of the plot.

Many commentators on Aristotle take his mention of poetic “requirements” to involve more specific conventions, especially those of different genres. We’ve long known that certain kinds of art works permit things that would be forbidden in other kinds. A children’s movie is unlikely to show chainsaw dismemberings, unless Eli Roth has been given a producing deal at Pixar. This idea of genre fitness or decorum has implications for coincidences too.

Clearly, coincidences flourish in comedy. The innocent young man trapped in a lady’s boudoir will have to hide under the bed because her husband bursts in at an awkward moment. In the long chase sequence through old Hong Kong in Project A (1983), Jackie Chan keeps bumping into his superior officer. Sometimes Jackie is set back by the encounter, but once the officer inadvertently rescues him. David Lodge writes: “Audiences of comedy will accept an improbable coincidence for the sake of the fun it generates.” His novel Small World culminates in a pile-up of coincidences in which an airline check-in clerk happens to give the heroine a copy of The Faerie Queene at the precise moment she needs to check a literary reference.

This is all highly implausible, but it seemed to me that by this stage of the novel it was almost a case of the more coincidences the merrier, provided they did not defy common sense, and the idea of someone wanting information about a classic Renaissance poem getting it from an airline Information desk was so piquant that the audience would be ready to suspend their disbelief.

Melodrama is another genre that relies on coincidences, particularly those that bring bad luck. (Think of Rock Hudson’s cliff-edge fall in All that Heaven Allows.) Likewise, I think that the revelations of the incriminating envelopes in Infernal Affairs and The Departed are partly motivated by genre conventions. In undercover tales, the detectives have to be alert for any physical items that might betray them or offer clues. So the envelopes are something that the hypersensitive narc could plausibly fasten onto. (Why the envelopes are left lying around in the first place is another part of the story, which I’ll come to.) Similarly, Initial D is partly a teenage romance, and we know that such films require an obstacle to happiness; that’s what Itsuki’s accidental discovery provides.

There’s another “requirement” of poetic art that can motivate coincidence, and it cuts across different genres. In Wilson Yip Wai-sun’s SPL (2005), a brutal martial-arts fight in a nightclub ends with the gangland chief Wong Po hurling Inspector Ma through a window far above the street.

Down below in a waiting car are Wong Po’s wife and baby son, the only things in life he loves.

Care to have a guess where Ma lands?

This is a coincidence motivated by poetic justice: The brutal Wong Po has inadvertently killed his wife and child. Serves him right!

As we might expect, Aristotle anticipated poetic justice too. He remarked that there was a special sense of fitness when the statue of a murdered man toppled over on his killer.

Three dimensions of narrative

Casablanca.

In an essay in Poetics of Cinema I argued that we can think of any narrative as having three dimensions: the story world, the macrostructure of the plot, and the narration–the flow of information as it’s presented, moment by moment, in the film. Each of these dimensions can motivate coincidence, and each answers to what Aristotle calls “requirements” specific to narrative art.

Say you want two characters to meet without making a rendezvous. One way is to establish that each has a routine. Jack stops for coffee at Starbuck’s every morning on the way to work; so does Jill. Sooner or later, it’s plausible that they will run into each other. The appeal to routine is probably behind the unlucky coincidence in I Corrupt All Cops. After being beaten, Unicorn staggers to the food stall across from his girlfriend’s apartment house–evidently on his way to call on her.

Another sort of story-world motivation involves characterization. In Initial D, it’s not implausible that the randy Itsuki would be hanging around outside a love hotel. Given his personality, he’s more likely to see Takumi there than other, more upright characters would be. In Infernal Affairs, Lau is a cautious mole, but he has no reason to hide the telltale dossier because he thinks it would be meaningless to anyone else. (Lau can’t know that Chan is the one who scribbled the corrected spelling on the envelope.) Lau’s studied nonchalance lets him stack papers on his desk without concern that this one is particularly revelatory.

Coincidence can also be motivated by the overall plot structure. If you start your film by alternating scenes showing two characters living their lives separately, you make it easier for your audience to accept what might otherwise seem a chance meeting between them later. After all, if they aren’t going to have some interaction, why are they both in this story? Sleepless in Seattle provides a clear-cut instance, although here the conventions of the romantic comedy genre also insist that the couple will get together. (Vera Chytilová’s Something Different of 1963 shrewdly defeats the expectation aroused by this sort of alternating construction.)

Likewise, a flashback structure can motivate coincidences. If we’ve seen the outcome of an action, even implausible events leading up to it can seem more natural. At the start of The Big Clock (1945) we see a hunted man hiding in a vast clock mechanism that surmounts a skyscraper.

In a long flashback, we see what led up to Stroud’s plight. Fired from his magazine job, he meets up with a blonde woman who takes him bar-hopping. They wind up in her apartment, but she hurries him out just as his boss Janoth comes in. Stroud watches Janoth go into the woman’s apartment.

The encounter isn’t wholly accidental. We know, as Stroud does not, that the woman is Janoth’s mistress, and she knows Janoth is coming to visit her. Nonetheless, what happens next leads to Stroud’s being fingered for murder. Stroud has pretty bad luck, but the opening frame story of his flight retroactively motivates his presence at the crime scene; we wouldn’t have the clock scene unless it proceeded, as Aristotle might say, by necessity from something pretty serious. The order of presentation coaxes us to accept whatever led up to the opening situation.

The story world and the plot macrostructure can do only so much. Sometimes coincidences need more fine-grained motivation. Here’s where narration, the patterned flow of information, comes in. If a cowardly cowboy is just about to leave the saloon when the bullying gunfighter enters, it can seem less stage-managed if we show, beforehand, the gunfighter riding into town with his minions. It doesn’t make the encounter more plausible in the story world, but it prepares us to find it more plausible: the two paths seem to converge. Here crosscutting accomplishes on the small scale what alternating scenes can do for macrostructure.

An even simpler tactic is to have someone announce that what’s happening is extremely unlikely. Lodge points out the audacity of Henry James in The Ambassadors when he presents a major moment through a character who reflects, “It was too prodigious, a chance in a million. . . ” This is the equivalent of Rick’s comment about Ilsa dropping into his gin joint. A frank admission of a coincidence can pull you through.

It was meant to be

Many of these motivating factors can work together with a more sweeping one. Recall that we’re sometimes tempted to consider everyday coincidence the result, or sign, of forces larger than we can comprehend–God, karma, fate, the Sibling Affinity Frequency. A narrative can motivate its coincidences by suggesting that they are working out an elusive but powerful pattern. Somehow, coincidence is just the hand of destiny. The French film known in English as Happenstance (2000) provides an example, but so does Serendipity (2001).

Jonathan and Sara meet cute in Manhattan, but mishaps separate them. They never learn each other’s identity. Years later, Sara is in San Francisco living with a musician, while Jonathan is about to get married. Vaguely dissatisfied and fretful, Sara returns to Manhattan to find Jonathan. Meanwhile, just before his marriage, he sets out to find her. Each one thinks that recapturing the love that flared up in one magical night would be worth one last effort.

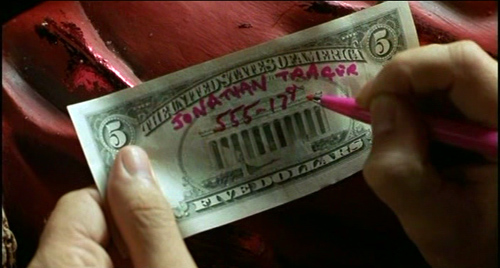

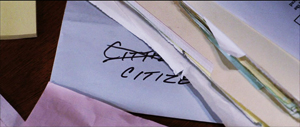

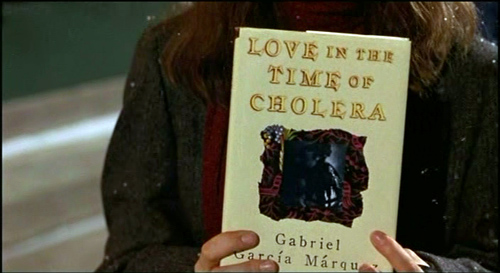

How do they find one another? Clues, plus coincidences. Jonathan starts to track Sara through a sales receipt for gloves she bought when they first bumped into each other. Sara returns to the Waldorf and visits “their” café in hope of finding some connection to Jonathan. But a lot of luck is involved too. Jonathan confirms Sara’s location thanks to her inscription in a used copy of Love in the Time of Cholera–a copy that his fiancée gives him, no less. By chance she bought Sara’s copy. Correspondingly, Sara finds the $5 bill Jonathan signed years before in her friend’s purse. Her friend got it as change at the café. The characters take purposive action, but they achieve their goals through coincidences.

These coincidences are simply outrageous. How can we motivate them? At the beginning of their magical night Sara announces that she believes that happy accidents are in fact controlled by fate. If she and Jonathan are meant to be together, things will arrange themselves the right way. She tells him this as they have coffee in her favorite café, Serendipity.

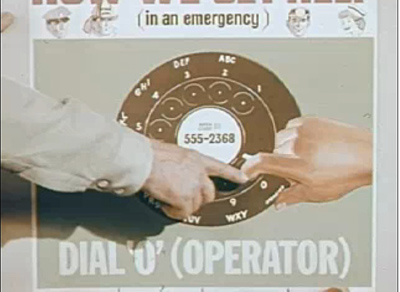

So Sara mounts some tests of their cosmic compatibility. She insists they leave the café separately: if they’re destined to remeet they will. Jonathan leaves his scarf behind, and she finds it, so they’re back together. She writes her contact information on a scrap of paper, but it blows away. “Fate’s telling us to back off,” Sara warns. Jonathan writes his phone number on the fiver, but she then pays for something with it, saying that if it returns to her, she’ll call him. In exchange, she’ll write her information in the Márquez novel and give it to a used bookshop; if he finds it, he can call her. Finally, at the Waldorf Astoria, each one is to get in a separate elevator car, pick a floor, and see if they’re in synch. It’s this test that leads him, through problems of timing, to lose her.

What motivates the cascade of coincidences, then, is the film’s starkly announced theme. In love, favorable coincidence is just serendipity; the film puts its operating procedure in Sarah’s mouth. To make your coincidences seem plausible, then, make your movie explicitly about how coincidences can be read as destiny.

But the theme doesn’t work on its own. Several of our other principles of motivation help out. For one thing we have Aristotle’s notion of common opinion: “What people say” about true love is that a couple is somehow meant for each other. In addition, of course, this is a romantic comedy, a kind of film that depends on separating and uniting lovers. We’d be very surprised, not to say disappointed, if these two didn’t wind up together. Genre helps motivate the way coincidences help out the couple.

Perhaps most interestingly, the “requirements of art” in Hollywood dramaturgy include a symmetrical play with motifs and character traits. Each lover is given a token—$5 bill, Márquez novel—and certain locales gain significance through repetition (Bloomingdale’s, the Waldorf, Serendipity, the skating rink). At the start of the film, Sara is the romantic, while Jonathan is more pragmatic. After a few years as a psychotherapist, however, she no longer trusts in fate. But by searching for her, Jonathan becomes a passionate believer in signs, reading everything around him as a possible trace of her presence. His pursuit of a love that defies likelihood moves his friend, the journalist Dean, to write a hypothetical obituary:

Even in certain defeat the courageous Trager secretly clung to the belief that life is not merely a series of meaningless accidents or coincidences. Uh-uh. But rather it’s a tapestry of events that culminate in an exquisite, sublime plan.

That plan is worked out through a traditional plot symmetry. Sara had found Jonathan’s scarf in the café at the start. At the climax, he discovers her jacket on a bench overlooking the ice rink where they shared their first date. (She had gone back there in a nostalgic mood earlier in the day.) Now, coming back for her jacket, she reunites with Jonathan. Hollywood’s use of tokens and props to develop the drama fits nicely with the theme of fate’s good offices. You could say that the vicissitudes of destiny are recruited to motivate some principles of classical plot construction.

Time out

You may dislike all the films I’m mentioning (Serendipity?! That’s a movie for wimps!). But my purpose here isn’t evaluative. I want to explore some principles that are used to make stories hang together, more or less. The same principles are present in what we sometimes call art films, from Bicycle Thieves to The Headless Woman. Coincidences abound in these movies, often motivated as the randomness of life, or n-degrees-of-separation, or mysterious larger forces that create correspondences (Paris nous appartient, the Three Colors trilogy of Kieslowski). Appeal to realism, to folk psychology, to genre, to thematic significance, and to formal unity can be found in virtually all narrative cinema. Here as elsewhere, I’m just trying to make such principles explicit and study how they work.

In thinking about those principles, I’m struck by one more way in which narratives need coincidences. What makes a story intriguing, or even worth paying attention to?

Here’s a story. I got up this morning, had breakfast with Kristin, went to school to take some frame enlargements from Hong Kong films, and dropped off the slides at a lab before coming home. Technically, it’s a story, but you yawned halfway through. To be engaging, stories need a remarkable situation or twist—a lover betrayed, a man pursued for a crime he didn’t commit, a cop discovering that his savior is his worst enemy, people who meet and fall in love and then lose one another.

We need, in short, something out of the ordinary. Coincidences, popping out from the bland backdrop of everyday life, can provide an uncommon event. At the start of a plot, they launch the action. At intervals, and with the proper motivation, they can be invoked if they liven things up. The effect may go back to the strangeness that Robert Wright suggests that we’re always on the lookout for.

Granted, the effect of motivation is to make coincidences seem less strange than they might otherwise seem. Most of these factors work to give the coincidences a sort of causal boost. Itsuki sees Natsuki because he’s at the love hotel, Chan/ Billy notices the envelope because he’s an alert cop, Jonathan and Sara get together again because they follow up clues and try really hard and anyhow an unseen hand (causally) shapes their fate, and so on. The coincidences are often covered by a causal alibi. That suggests that what’s most coincidental in these situations is timing.

Most movie coincidences run on tight schedules. A few moments later, Itsuki wouldn’t have seen Natsuki leave the love hotel; Unicorn wouldn’t have caught his wife with his boss; Chan/ Billy wouldn’t have found the telltale envelope; and so on. As the film unrolls, we want our extraordinary events tied to close shaves, barely missed messages, and revelations taking place under a ticking clock.

Every moment in filmic storytelling seems to bristle with possibilities of convergence and revelation. The sort of actions that make stories interesting are even more gripping if they take place under time pressure. Very often, if a key event had happened slightly earlier or later, there would have been no coincidence. And movies, unrolling at a pace to which we all submit, are well-suited to arouse our interest with turns of events that might, just barely, have been very different. Perhaps we accept the power of good or bad timing because, to recall Aristotle, “people often think” things like this: If I had missed that train, I would never have met my soul mate. . . .

Clearly, though, timing is a tale for another occasion.

My thanks to Ben Brewster for discussing these ideas with me and reminding me of the Chinese adage. That precept is briefly discussed in Kam-ming Wong, “‘No Coincidence, No Story’: The Esthetics of Serendipity in Chinese Fiction,” International Readings in Theory, History and Philosophy of Culture (St. Petersburg, Russia: EIDOS, 2003), Vol.16, 180-97.

My references to the Poetics come from Stephen Halliwell’s edition, The Poetics of Aristotle: Translation and Commentary (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1987), pp. 40, 42, and 63. My extracts from David Lodge’s The Art of Fiction (New York: Viking, 1993) are from his section on coincidence, pp. 149-153.

Hilary P. Dannenberg’s book, Coincidence and Counterfactuality: Plotting Time and Space in Narrative Fiction (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2008) includes many intriguing ideas about coincidence. Her focus is the “coincidence plot” in which people realize they’re related to one another. Some of her arguments are presented in more compact form in her article, “A Poetics of Coincidence in Narrative Fiction,” Poetics Today 25: 3 (Fall 2004), pp. 399-436.

P.S. 31 September: In a study of The Pledge, film scholar Gary Bettinson has a valuable discussion of how coincidence can be motivated to resolve a plot. It’s available here.

Serendipity.