Archive for September 2010

The buddy system

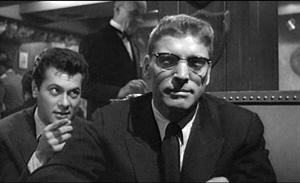

Sweet Smell of Success.

DB here:

Many of our friends write books, and what are friends for if not occasionally to promote each other’s books? Here’s an armload of titles, most of them recently published. They’re so good that even if the authors weren’t our friends and colleagues, I’d still recommend them.

James Naremore has made major contributions to film studies since his fine monograph on Psycho, published way back in 1973. That book remains one of the most sensitive analyses of this much-discussed movie. Now he has another monograph, on the stealth classic Sweet Smell of Success. When I was coming up, Alexander Mackendrick wasn’t much appreciated, and this movie slipped under the radar. More recently it has emerged as one of the model films of the 1950s, and not just for James Wong Howe’s spectacular location cinematography. It’s a very brutal story, with Tony Curtis playing against type as venal press agent Sidney Falco and Burt Lancaster as J. J. Hunsecker, a monstrously vindictive newspaper columnist.

Jim’s book provides a scene-by-scene commentary but also more general analysis of production circumstances and directorial technique. An enlightening instance is what Mackendrick called “the ricochet”—when character A talks to character B but is aiming at character C. This allows the filmmaker great flexibility in framing and cutting, often showing C’s reactions while we hear the dialogue offscreen. In the shots surmounting this blog, Sidney is needling J. J. by asking the Senator if he approves of capital punishment. Jim’s book joins his work on Welles, Kubrick, and film noir as part of a subtle reassessment of American postwar cinema.

With the current revival of interest in André Bazin’s film theory, it’s fruitful to look again at the “classical” theoretical tradition in which he participated. “Classical” here refers to the very long period before the emergence of semiotic and psychoanalytic theories of cinema in the 1960s. The newer theories have somewhat beclouded our recognition of how imaginative and wide-ranging the old folks were. In Doubting Vision: Film and the Revelationist Tradition, Malcolm Turvey scrutinizes four thinkers who saw film as having the power to show us things beyond (or above, or below) surface reality. In the spirit of analytic philosophy, Turvey carefully lays out the positions of Béla Balázs, Jean Epstein, Siegfried Kracauer, and Dziga Vertov before asking whether their claims hold up.

With the current revival of interest in André Bazin’s film theory, it’s fruitful to look again at the “classical” theoretical tradition in which he participated. “Classical” here refers to the very long period before the emergence of semiotic and psychoanalytic theories of cinema in the 1960s. The newer theories have somewhat beclouded our recognition of how imaginative and wide-ranging the old folks were. In Doubting Vision: Film and the Revelationist Tradition, Malcolm Turvey scrutinizes four thinkers who saw film as having the power to show us things beyond (or above, or below) surface reality. In the spirit of analytic philosophy, Turvey carefully lays out the positions of Béla Balázs, Jean Epstein, Siegfried Kracauer, and Dziga Vertov before asking whether their claims hold up.

I’m not giving much away by revealing that Malcolm thinks the revelationist tendency has its problems. But his purpose isn’t simply to reject the position. He treats it as an instance of what he calls “visual skepticism,” the idea that we ought to treat our ordinary intake of the world as something suspect. This idea, Malcolm argues, is central to modernism in the visual arts. He extends his critique of visual skepticism to more recent theorists as well, notably Gilles Deleuze, and he shows how his own ideas apply to films by Hitchcock, Brakhage, and other directors. Malcolm’s book is a model of theoretical clarity and probity, and a stimulating read as well.

Skepticism of another sort is central to Carl Plantinga’s Rhetoric and Representation in Nonfiction Film. One result of semiotic theory was to question whether a film could ever adequately represent reality. If a movie is only an assembly, however complex, of conventional signs, it can’t give us access to something out there. Even a documentary, some theorists argued, had no privileged access to the real world, let alone to general truths. “Every film is a fiction film” was a refrain often heard at the time. Carl tackles this assumption head-on by carefully arguing that just because a documentary is selective, or biased, or rhetorical, that doesn’t mean that it can’t affirm true propositions about our social lives.

Like Malcolm, Carl brings a philosopher’s training in conceptual analysis to debates about the ultimate objectivity of any documentary. In adopting a position of “critical realism” opposed to skepticism, Carl examines the realistic status of images and sounds, the way documentaries are structured, and filmmakers’ use of technique. He shows, convincingly to my mind, that a documentary may offer an opinion and still be objective and reliable to a significant degree. Carl’s 1997 book went out of print before it could be published in paperback. He has enterprisingly reissued it as a print-on-demand volume, and it’s available here.

To take film theory in another direction, there’s Evolution, Literature, and Film, edited by Brian Boyd, Joseph Carroll, and Jonathan Gottschall. As a wider audience has become aware of the power of neo-Darwinian thinking, more and more scholars have been arguing that evolutionary theory can shed light on aesthetics. The most visible effort recently is Denis Dutton’s The Art Instinct.

To take film theory in another direction, there’s Evolution, Literature, and Film, edited by Brian Boyd, Joseph Carroll, and Jonathan Gottschall. As a wider audience has become aware of the power of neo-Darwinian thinking, more and more scholars have been arguing that evolutionary theory can shed light on aesthetics. The most visible effort recently is Denis Dutton’s The Art Instinct.

For some years Brian, Joe, and Jonathan have been in the forefront of this trend, with many books and articles to their credit. Their anthology pulls together broad essays on biology, evolutionary psychology, and cultural evolution before turning to art as a whole and then focusing on literature and cinema. There are also pieces displaying evolutionary interpretations of particular works, and a finale that provides examples of quantitative studies of genre, gender variation, and sexuality, including an article called “Slash Fiction and Human Mating Psychology.”

Among the film contributors are other friends like Joe Anderson, a pioneer in this domain with his 1996 book The Reality of Illusion, and Murray Smith, who provides an acute piece called “Darwin and the Directors: Film, Emotion, and the Face in the Age of Evolution.” There are also essays of mine, drawn from Poetics of Cinema. In all, this book presents a persuasive case for an empirical, broadly naturalistic approach to the arts.

By the way, the same team is involved with an annual, The Evolutionary Review, edited by Alice Andrews and Joe Carroll. Its first issue offers articles on Facebook, musical chills, women as erotic objects in film, and Art Spigelman’s In the Shadow of No Towers (by Brian Boyd).

Some books emerge from conferences, and Tom Paulus and Rob King’s Slapstick Comedy is a good instance. Based on “(Another) Slapstick Symposium,” held at the Royal Film Archive of Belgium in 2006, the anthology brings together a host of experts who look back at madcap comedy in American silent film. There are essays on particular creators—Griffith, Sennett, Fatty, and Chaplin, inevitably—as well as pieces on slapstick parodies of other movies and the genre’s relation to modernity, also inevitably. Tom Gunning offers a fine analysis of Lloyd’s Get Out and Get Under (1920), concentrating on a complex string of gags around an automobile. The collection gathers work by some of the outstanding scholars of silent film while also, of course, making you want to see these crazy movies again.

You also want to see all the movies lovingly evoked by Gary Giddins in Warning Shadows: Home Alone with Classic Cinema. As indicated in another blog entry, I find Giddins one of the best appreciative critics we’ve ever had. Any essay, indeed almost any sentence, cries out to be quoted. Here he is on Edward G. Robinson:

You also want to see all the movies lovingly evoked by Gary Giddins in Warning Shadows: Home Alone with Classic Cinema. As indicated in another blog entry, I find Giddins one of the best appreciative critics we’ve ever had. Any essay, indeed almost any sentence, cries out to be quoted. Here he is on Edward G. Robinson:

His round, thick-lipped, putty face could brighten like paternal sunshine or shut down in implacable contempt or stall with crafty desperation or pontificate with ingenuous wisdom; his short, stumpy, erect frame could sport a tailor-made as smartly as Cary Grant.

Some of the pieces in Giddins’ latest collection were designed to accompany DVDs, but they will outlast this evaporation-prone genre. Other reviews come from the New York Sun, which gave him freedom to mix and match his subjects: Young Mr. Lincoln and Lust for Life (both biopics), Lady and the Tramp and Miyazaki movies. The collection opens with Giddins’ thoughts on how changes in film exhibition, from nickelodeons to digital screens, have altered our relationship with the movies. This isn’t just nostalgia, because his survey allows him to celebrate the power of DVD to exhume forgotten titles. The standards for a film classic, he notes, “are gentler and more flexible” than those in appraising other arts. “The passing decades are a boon to the appreciation of stylistic nuance that gives certain melodramas and genre pieces the heft of individuality.”

Who was Segundo de Chomón? In the 1970s, I kept finding that films I thought were by Méliès turned out to bear this mysterious signature. You imagine a man in a cape and a floppy hat. Photographs show someone a little less operatic, but with a superb mustache. Today he’s far from a mystery, although many of his movies can’t be fully identified. Several scholars have followed his trail, none more thoroughly than Joan M. Minguet Batllori in Segundo de Chomón: The Cinema of Fascination.

Chomón started as a cinema man-of-all-work in Barcelona, translating film titles, distributing copies, and producing films for Pathé. After moving to Paris in 1905, he continued working for the company and established his fame with trick films. He returned to Barcelona to create a production company, but that failed. On he went to Italy, where he specialized in visual effects, most famously for Cabiria (1914).

In his Parisian Pathé years, he was in charge of all the studio’s trick films, which included not only stop-motion, superimpositions, and other effects but also marionettes and animation. Joan argues that he was a prime exponent of the “cinema of attractions,” Tom Gunning’s term for that early mode of filmmaking which aims to startle and enchant the audience. A famous instance is Kiriki, acrobats japonais (1907), which shows gravity-defying stunts.

Chomón accomplished this by shooting from straight down, filming the performers on the floor. They had to simulate leaps and flips as they rolled along each other’s bodies, and then they had to slip perfectly into position. This English edition of Joan’s book on Chomón, full of information and providing a “provisional filmography” along with many pages of gorgeous color images, will be available soon here.

We recently noted the anniversary of our book on classic studio cinema, a 1985 project in which we bypassed talking about exhibition. That part of the industry has been a scholarly growth area in the years since, and one of the newest yields is Epics, Spectacles, and Blockbusters: A Hollywood History, by Sheldon Hall and Steve Neale. It’s a chronological account of Big Movies, from the earliest features to the digital era, and it concentrates on how such films have been marketed and shown. It explains how exhibition changed across the decades, and how we got the phenomenon of the “roadshow” movie, the film shown selectively (only certain cities), at intervals (perhaps only one matinee and one evening screening), and at more or less fixed prices. My middle-aged readers will remember roadshow releases like The Sound of Music (1965), although there were many before and even a few since.

We recently noted the anniversary of our book on classic studio cinema, a 1985 project in which we bypassed talking about exhibition. That part of the industry has been a scholarly growth area in the years since, and one of the newest yields is Epics, Spectacles, and Blockbusters: A Hollywood History, by Sheldon Hall and Steve Neale. It’s a chronological account of Big Movies, from the earliest features to the digital era, and it concentrates on how such films have been marketed and shown. It explains how exhibition changed across the decades, and how we got the phenomenon of the “roadshow” movie, the film shown selectively (only certain cities), at intervals (perhaps only one matinee and one evening screening), and at more or less fixed prices. My middle-aged readers will remember roadshow releases like The Sound of Music (1965), although there were many before and even a few since.

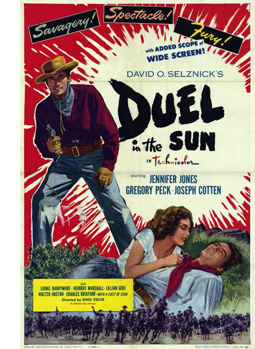

Sheldon and Steve trace in unprecedented detail the cycles of blockbusters that have run throughout American cinema. In the process they refreshingly redefine the very idea. We don’t usually think of The Best Years of Our Lives as a Big Movie, but it runs three hours and was considered a “special” production, comparable to the more obvious sprawl of Duel in the Sun. The authors bring the story up to date by considering today’s event movies as a “Cinema of Spectacular Situations.” Yes, that category includes comic-book films, Inception, and, of course, the 3D sagas that may finally be wearing out their welcome. (My editorializing, not theirs.)

Japanese cinema is endlessly fascinating in all its eras; I’d argue that in toto it’s one of the three greatest national cinemas in film history. The postwar period is exceptionally interesting because of the American occupation (1945-1951) and its effects on Japanese film culture. This period has already provoked one of the best books we have on Japanese cinema, Kyoko Hirano’s Mr. Smith Goes to Tokyo, and it finds a worthy accompaniment in Hiroshi Kitamura’s Screening Enlightenment: Hollywood and the Cultural Reconstruction of Defeated Japan. Kyoko focused on how US policy shaped domestic filmmaking, while Hiroshi asks how the Occupation helped American studios penetrate the local market.

Over six hundred Hollywood movies poured into Japan during the period, and Hiroshi traces how local tastemakers as well as U.S. policymakers drew audiences to them. Young Japanese learned about the Academy Awards, assembled in movie-study clubs to discuss what they were seeing, and were urged to consider even a gangster tale like Cry of the City (1950) as demonstrating the humanistic side of democracy. A center of this activity was Eiga no tomo (“Friends of the Movies”), a magazine that went beyond entertainment news and tried to reshape the tastes of young people. In sharp prose and vivid evidence, Hiroshi captures the ways in which American cinema promised to help heal a devastated country.

The Danish Directors, by Mette Hjort and Ib Bondebjerg, has become a standard companion to the most successful “small cinema” on the European scene. Now it has a successor in The Danish Directors 2: Dialogues on the New Danish Fictional Cinema, edited by Mette, Eva Jorholt, and Eva Novrup Redvall. Once again, we get lengthy, in-depth interviews covering the value of film education, the vagaries of funding, and filmmakers’ creative decision-making. Lone Scherfig, Christoffer Boe, Per Fly, Paprika Steen, and many other major figures are included. (Disclosure: The editors were kind enough to dedicate the book to me.)

The Danish Directors, by Mette Hjort and Ib Bondebjerg, has become a standard companion to the most successful “small cinema” on the European scene. Now it has a successor in The Danish Directors 2: Dialogues on the New Danish Fictional Cinema, edited by Mette, Eva Jorholt, and Eva Novrup Redvall. Once again, we get lengthy, in-depth interviews covering the value of film education, the vagaries of funding, and filmmakers’ creative decision-making. Lone Scherfig, Christoffer Boe, Per Fly, Paprika Steen, and many other major figures are included. (Disclosure: The editors were kind enough to dedicate the book to me.)

While the first volume is a rich storehouse of information on Danish film in “the Dogma era,” the newest volume shows how directors (some of whom made Dogma projects) have gone beyond it. In preparing 1:1, a film about Danes and Arab immigrants living in a housing project, Annette K. Olesen had a full script but concealed it from the non-professional cast. After getting the performers comfortable with ordinary situations, she began staging scenes while encouraging improvisation. Screenwriter Kim Fupz Aakeson incorporated the improvised material into revisions of the script.

By contrast, the prolific director-screenwriter Anders Thomas Jensen (Adam’s Apples, The Green Butchers), relies on strong structure, with lean expositions and sharply defined climaxes. He appreciates clean filming technique too.

It’s easy to make something that’s ugly and handheld, but you have to take telling stories with images seriously. You have to take the language of film seriously. Many Danish directors have started doing this in recent years and it’s wonderful, because there was a time when everything looked Dogma-like and I found myself thinking, “It’s got to stop now.”

To those who think that Danish cinema is at risk of becoming a cinema of cozy liberal reassurance, this collection offers many salutary signs. Every director speaks of the need to keep innovating, to push ahead provocatively. Simon Staho, whose Day and Night seems to me one of the most adventurous Danish films of recent years, aims at utter purity: “My task is to figure out how to add as little as possible to the black screen. The damned problem is that you have to add image and sound!”

What makes all these books exciting to me is a willingness to test ideas–sometimes very general ones–about cinema and the wider world by examining film as a distinctive art form. Even the most conceptual books on this week’s shelf are firmly rooted in the particular choices that creators make and the concrete ways that viewers respond.

Next stop: Vancouver International Film Festival. Whoopee!

Day and Night.

What makes Hollywood run?

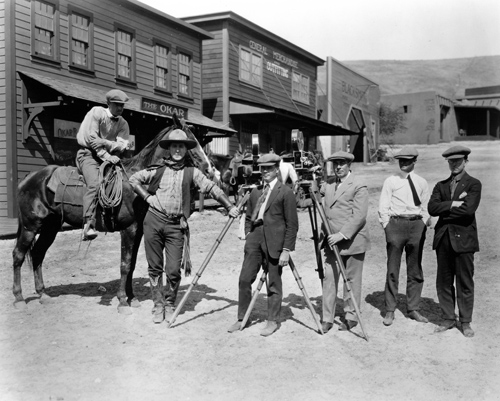

William S. Hart and crew at Inceville, 1910s.

DB here:

For decades most people had a sketchy idea of The Hollywood Studio Film. Boy meets girl, glamorous close-ups, spectacular dance numbers or battle scenes, happy endings, fade-out on the clinch. But even if such clichés were accurate, they didn’t cut very deep or capture a lot of other things about the movies. Could we go farther and, suspending judgments pro or con the Dream Factory, characterize U. S. studio filmmaking as an artistic tradition worth studying in depth? Could we explain how it came to be a distinctive tradition, and how that tradition was maintained?

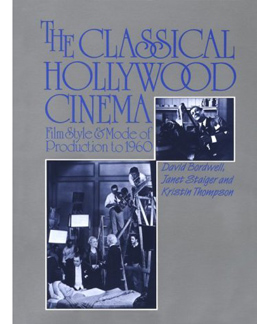

In 1985 Routledge and Kegan Paul of London published The Classical Hollywood Cinema: Film Style and Mode of Production to 1960. Kristin, Janet Staiger, and I wrote it. Since it’s rare for an academic film book to remain in print for twenty-five years, we thought we’d take the occasion of its anniversary to think about it again. Those thoughts can be found in the adjacent web essay, where we three discuss what we tried to do in the book, spiced with comments about areas of disagreement and more recent thoughts. This blog entry is just a teaser.

A touch of classical

John Arnold, a Bell & Howell camera, and Renée Adorée in 1927.

The prospect of analyzing Hollywood as offering a distinctive approach to cinematic storytelling emerged slowly. The earliest generations of film historians tended to talk about the emergence of film techniques in a rather general way. For example, historians were likely to trace the development of editing as a general expressive resource, appearing in all sorts of movies. While they recognized that, say, the Soviet filmmakers made unusual uses of this technique, writers still tended to think of editing as either a fundamental film technique or a very specific one—e.g., Eisenstein’s personal approach to editing.

An alternative approach was to understand the history of film as an art as a stream of cinematic traditions, or modes of representation, within which filmmakers worked. From this angle, there was a Hollywood or “standard” or “mainstream” conception of editing, and this didn’t exhaust all the creative possibilities of the technique. But it went beyond the inclinations of any particular director. People had long recognized that there were group styles, like German Expressionism and Italian Neorealism, but it took longer to start to think of mainstream moviemaking as, in a sense, a very broad and fairly diverse group style.

In the late 1940s André Bazin and his contemporaries started to point out that different sorts of films had standardized their forms and styles quite considerably. Bazin attributed the success of Hollywood cinema to what he called “the genius of the system.” In my view, his phrase referred not to the studio system as a business enterprise but rather to an artistic tradition based on solid genres and a standardized approach to cinematic narration. This artistic system, he suggested, had influenced other cinemas, creating a sort of international film language.

The idea that there was a dominant filmmaking style, tied to American studio moviemaking, was developed in more depth during the 1960s and 1970s. Christian Metz’s Grande Syntagmatique of narrative film pointed toward alternative technical choices available in the “ordinary film.” Raymond Bellour’s analysis of The Birds, The Big Sleep, and other films pointed to a fundamental dynamic of repetition and difference governing American studio cinema. Somewhat in the manner of Roland Barthes’ S/z, Thierry Kuntzel’s essays explored M and The Most Dangerous Game looking for underlying representational processes that were characteristic of studio films. From a somewhat different angle, in the book Praxis du cinema and later essays Noël Burch traced out a dominant set of techniques that formed what he would eventually call the “Institutional Mode of Representation.” The Cahiers du cinéma critics famously posited different categories of filmic construction, each one tied to the representation of ideology. In English, Raymond Durgnat was an early advocate of studying what he called the “ancienne vague,” the conventional filmmaking that young directors were rebelling against.

The trend was given a new thrust by the British journal Screen, which disseminated the idea of a “classical narrative cinema,” a mode of representation characterized by distinctive dynamics of story, style, and ideology. Perhaps the most emblematic article of this sort was Stephen Heath’s in-depth analysis of Touch of Evil. Over the same years a new generation of film historians was studying early cinema with unprecedented care, and they too were finding a variety of modes of representation at work in filmmaking of the pre-1920 era.

The effect was to relativize our understanding of Hollywood. Mainstream U. S. commercial filmmaking wasn’t the cinema, merely one branch of film history, one way of making movies. Breaking a scene into a coherent set of shots, to take the earlier example, wasn’t Editing as such. It was one creative choice, although it had become the dominant one. And what made Hollywood’s brand of coherence the only option? Eisenstein, Resnais, Godard, and other filmmakers explored unorthodox alternatives.

Nearly all of the influential research programs of the period emphasized the film as a “text.” This wasn’t surprising, since several of the writers were working with concepts derived from literary semiotics and structuralism. At the same period, other scholars were developing ideas about Hollywood as a business enterprise. Douglas Gomery, Tino Balio, and a few others were showing that the studio system was just that—a system of industrial practices with its own strategies of organization and conduct. But most of those business studies did not touch on the way the movies looked and sounded, or the way they told their stories.

Could the two strains of research be integrated? Could one go more deeply into the films and extract some pervasive principles of construction? And could one go beyond the films and show how those principles of style and story connected to the film industry?

The prospect of integrating these various aspects—and, naturally, of finding out new things—intrigued us.

Secrets of the system

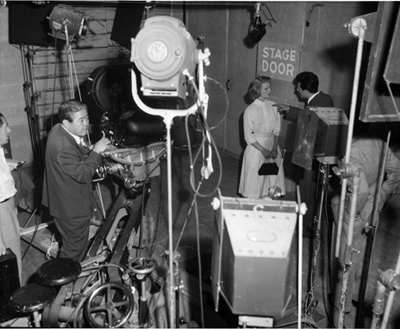

Main Street to Broadway (1953, MGM release). Cinematographer James Wong Howe on left.

The overall layout of CHC tried to answer these questions while weaving together a historical overview. Part One, written by me, provided a model or ideal type of a classical film, in its narrative and stylistic construction. Part Two, by Janet, outlined the development of the Hollywood mode of production until 1930. In Park Three, Kristin traced the origins and crystallization of the style, from 1909 to 1928. Part Four included chapters by all three authors on the role of technology in standardizing and altering classical procedures during the silent and early sound era. In Part Five Janet resumed her account of the mode of production, tracing changes from 1930 to 1960. The technology thread was brought up to date in Part Six, where I discussed deep-focus cinematography, Technicolor, and the emergence of widescreen cinema. Part seven, which Janet and I wrote together, pointed out implications of the study and suggested how Hollywood compared with alternative modes of film practice.

Clearly, CHC was several books in one. Janet could easily have written a free-standing account of the mode of production. Kristin could have done a book on silent film technique and technology. I could have focused on style and form, using sound-era technologies as test cases. The point of interspersing all these studies (and creating a slightly cumbersome string of authorial tags within sections) was to trace interdependences. For instance, Kristin examined the emerging stylistic standardization in the 1910s. Janet showed how that standardization was facilitated by a systematic division of labor and hierarchy of control, centered around the continuity script. At the same time, the organization of work was designed to permit novelties in the finished product, a process of differentiation that is important in any entertainment business.

Moreover, once the stylistic menu was standardized, it reinforced and sometimes reshaped the mode of production. At every turn we found these mutual pressures, a mostly stable cycle among tools, artistic techniques, and business practices. Once the studios became established, they needed to outsource the development of new lighting equipment, camera supports, microphones, make-up, and other tools. A supply sector grew up, carrying names like Eastman, Bell & Howell, Mole-Richardson, Western Electric, and Max Factor. But the suppliers had to learn that they couldn’t innovate ad libitum. The filmmakers laid down conditions for what would work onscreen and what would fit into efficient craft routines. In turn, the routines could be adjusted if a new tool yielded artistic advantages. And the whole process was complicated by an element of trial and error. The film community often couldn’t say in advance what would work; it could only react to what the supply firms could provide.

Moreover, once the stylistic menu was standardized, it reinforced and sometimes reshaped the mode of production. At every turn we found these mutual pressures, a mostly stable cycle among tools, artistic techniques, and business practices. Once the studios became established, they needed to outsource the development of new lighting equipment, camera supports, microphones, make-up, and other tools. A supply sector grew up, carrying names like Eastman, Bell & Howell, Mole-Richardson, Western Electric, and Max Factor. But the suppliers had to learn that they couldn’t innovate ad libitum. The filmmakers laid down conditions for what would work onscreen and what would fit into efficient craft routines. In turn, the routines could be adjusted if a new tool yielded artistic advantages. And the whole process was complicated by an element of trial and error. The film community often couldn’t say in advance what would work; it could only react to what the supply firms could provide.

In the late 1920s, for instance, sound recording made the camera heavier than the tripods of the silent era could bear. Supply firms engineered “camera carriages” that could wheel the beast from setup to setup. But this development occurred soon after filmmakers had noticed the expressive advantages of the “unleashed camera” in German films and some American ones. So the camera carriage became a dolly, redesigned to permit moving the camera while filming. It’s not that there weren’t moving-camera shots before, of course, but with the camera permanently on a mobile base, tracking and reframing shots could play a bigger role in a scene’s visual texture. Similarly, studio demands for ways of representing actors’ faces in close-ups forced Technicolor engineers back to their drawing boards again and again. Once the problem of rendering faces pleasant in color was solved, filmmakers could then redesign their sets and adjust their make-up to suit the vibrant three-strip process. And the interaction of work, tools, and style triggered larger cycles of activity. The need to pool information about stylistic demands and technological possibilities helped foster the growth of professional associations and the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences.

This give-and-take among the studios, the supply sector, and the stylistic norms had never been discussed before, and we couldn’t have done justice to it in separately published books. Nor could isolated studies have easily traced how industrial discourses—the articles in trade journals, the communication among the major players—helped weld the mode of production to artistic choices about filmic storytelling.

The Classical Hollywood Cinema was generously reviewed, in terms that made us feel our hard work had been worth it. Books we’ve written since haven’t been so widely acclaimed. (Nothing like peaking young.) We’re grateful to the reviewers who praised the book, and to the teachers and students who have strengthened their biceps by picking it up to read. Of course there are others who don’t consider the project worthwhile; the TLS reviewer called it “sludge.” Probably nothing we say in the accompanying essay will persuade those readers to take a second look. Without responding to all the criticisms the book received (that would take a book in itself), our accompanying essay tries to position this 1985 project within our current lines of thinking.

We studied how Hollywood routinized its work, but that doesn’t mean that we think division of labor is always alienating. It may produce a much better outcome than do the efforts of a solitary individual. For us, that’s what happened during this rewarding exercise in collaboration.

Our thinking was shaped by many sources; here are some of them.

For André Bazin on “the genius of the system,” see “La Politique des auteurs,” in The New Wave, ed. Peter Graham (New York: Doubleday, 1968), pp. 143, 154, and “The Evolution of the Language of Cinema,” in What Is Cinema? ed. and trans. Hugh Gray (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1967), pp. 23-40. Christian Metz explains the Grande Syntagmatique of the image track in “Problems of Denotation in the Fiction Film,” Film Language, trans. Michael Taylor (New York: Oxford University Press, 1974), 108-146. Raymond Bellour’s essays of the period are available in The Analysis of Film. Thierry Kuntzel’s essay on The Most Dangerous Game was translated into English as “The Film-Work 2,” Camera Obscura no. 5 (1980), 7-68. An important gathering of essays in this line of inquiry is Dominique Noguez, ed., Cinéma: Théorie, lectures (Paris: Klincksieck, 1973).

Noël Burch’s early ideas are set out in Theory of Film Practice, trans. Helen R. Lane (New York: Prager, 1973). Even more important to our project was Noël Burch and Jorge Dana, “Propositions,” Afterimage no. 5 (Spring 1974), 40-66, and Burch’s To the Distant Observer: Form and Meaning in Japanese Film (London: Scolar Press, 1979), available online here.

Raymond Durgnat’s series, “Images of the Mind,” deserves to be republished, preferably online. The most relevant installments for this entry are “Throwaway Movies,” Films and Filming 14, 10 (July 1968), 5-10; “Part Two,” Films and Filming 14, 11 (August 1968), 13-17; and “The Impossible Takes a Little Longer,” Films and Filming 14, 12 September 1968), 13-16. Stephen Heath’s analysis of Touch of Evil may be found in “Film and System: Terms of Analysis,” Screen 16, 1 (Spring 1975), 91-113 and 16, 2 (Summer 1975), 91-113.

Barry Salt’s Film Style and Technology: History and Analysis (London: Starword, 1983) works in comparable areas to CHC, though without our interest in industry-based sources of stability and change. The newest edition is here.

Tino Balio’s courses and his collection The American Film Industry (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1976) had a substantial influence on us. He has been a wonderful friend and guide for us all since the 1970s. Our friendship with Douglas Gomery dates from our early days in Madison. Many conversations, along with his teaching in our program, shaped our thinking. A good summing up his of decades of work on the business and economics of Hollywood is The Hollywood Studio System: A History (London: British Film Institute, 2008).

Some of the stylistic traditions discussed in this entry are discussed in my On the History of Film Style. Several blog entries on this site fill in more details; click on the category “Hollywood: Artistic traditions.”

PS 26 September 2010: Douglas Gomery reminds me that the idea of sampling Hollywood films in an unbiased fashion–one feature of our method in CHC–was suggested to us by Marilyn Moon, economist extraordinaire. I’m happy to thank Marilyn, along with Joanne Cantor and Douglas himself, who helped us devise a sampling procedure.

Actors and set for Blondie Johnson (Warners, 1933).

Bond vs. Chan: Jackie shows how it’s done

DB here:

During the 1990s several critics began to notice that filmmakers were doing something odd with action scenes.

Directors were consciously, even joyously, sacrificing clarity. When two characters were punching it out, the framing didn’t make it easy to know who was hitting whom, and how. Changes in angle and shot scale were sometimes so abrupt that you had little time to adjust. The cutting pace was so quick that you couldn’t entirely register the movement in shot A before shot B replaced it. Sometimes the spatial layout of the fight was confusing as well: too many close views, too few master shots. Later, the return of handheld shooting made many action scenes even more illegible, blurring and smearing them to the point that sound (as in the Bourne films) had to specify that a body has hit a window or a hand has busted a bottle. Now we have Sylvester Stallone’s The Expendables, which might be a new summit in overbusy, incoherent, inconsequential action.

I wrote about this trend back in the 1990s, and I’ve returned to it on occasion since. Other writers, notably Todd McCarthy of Variety, noticed it too. He referred to the full-throttle editing and “frequently incoherent staging” on display in Armageddon (1998): “Bay’s visual presentation is so frantic and chaotic that one often can’t tell which ship or characters are being shown, or where things are in relation to one another.”

A decade later comes Peter DeBruge’s review of the “muddled execution” of The Expendables: Staging simultaneous fights “might’ve worked had the editors assembled all that footage in such a way that we could tell where characters are in relation to one another or what’s going on.”

The Michael Bay approach has become the principal way in which action scenes are shot. It isn’t absence of craft that leads to these aimless bouts. The filmmakers actively want the action to be hard, even impossible, to follow. Sometimes I think that this blurred bustle is there to secure a PG-13 rating; if you could really see the mayhem, we might be moving toward an R. But filmmakers don’t say that they’re self-censoring. They seem to think that making the action illegible is creative because it promotes realism.

Stallone explains why he scrambled up the fight scenes in The Expendables.

I don’t think many action scenes are shown from the character’s point of view. They are more from the director’s point of view. On Rambo, I thought the most economical and original way to shoot [the action] would be through Rambo’s eyes—if he were directing, what would his style be? But The Expendables is an ensemble picture, so it’s somewhat of a blend. I thought, ‘This is not supposed to hang in the Louvre.’ I wanted it to be disjointed and rough, not choreographed. If you really were filming a big battle with five cameras, [their footage] would not all flow together, so we set up the [cameras] to film the action we’d scripted and told the operators they were on their own. We said, ‘Do the best you can, and we’ll use the interesting shots from the characters’ perspectives.’”

Camera operator Vern Nobles describes shooting the action as “multi-camera craziness.”

You might point out that if somebody were really filming a big fight with five cameras, at least a couple of camera operators would be shot or punched silly. And presumably a few times we’d actually see other cameras.

Realism, as usual, is simply a fig leaf for doing what you want. Virtually any technique can be justified as realistic according to some conception of what’s important in the scene. If you shoot the action cogently, with all the moves evident, that’s realistic because it shows you what’s “really” happening. If you shoot it awkwardly, that presentation is “realistically” reflecting what a participant perceives or feels. If you shoot it as “chaos” (another description that Nobles applies to the Expendables action scenes)—well, action feels chaotic when you’re in it, right?

Forget the realist alibi. What do you want your sequence to do to the viewer? Do you want it to pass along an impression of bustle and flurry? Or do you want to make the viewer wince, recoil, even mildly reenact the movements of the players? Then follow the Hong Kong tradition. Yuen Woo-ping once told me that his goal was to make the viewer “feel the blow.” To convey the effort and strain, the impact and pain: that’s something worth doing.

It’s something that the blur-o-vision tussles lack, but even fights that are more carefully filmed are strangely unmoving. In Tomorrow Never Dies (1997), there’s a fistfight on a catwalk above a rotary press line. The presentation is more or less spatially unified, but it lacks drive because of certain creative choices. For instance, when Bond punches a security guard, the man simply drops out of the frame.

Where does he go? He doesn’t fall off the catwalk but seems to grab the railing, so maybe he’ll return for another go-round. But he doesn’t. As Bond falls back, another guard sneaks up on him. The framing and screen direction suggest that he’s approaching Bond from the front.

Actually, he’s sneaking up from the rear.

When Bond turns, we don’t see his punch.

In fact, we don’t see much of anything. Although the attacker is erect in one shot, he seems to be kneeling in the next, when Bond kicks him, somewhere below the frameline.

The attacker is standing again in the next shot, and he’s flung backward by the force of Bond’s unseen kick.

When the man returns, he tries to tackle Bond. At least, I think he does. The maneuver takes place, again, underneath the frameline.

At last we get a wider shot, but this serves mainly to align the fight with the conveyor belt below the men; guess who will fall?

More fighting, with punches and grappling blocked by the men’s bodies, culminates in Bond’s adversary falling into the print run.

Even here, however, we don’t really see what happens to the victim. He plunges through the river of newsprint and the machine starts belching.

Overall, we get a mild impression of what happened in the fight, but the action unfolds vaguely and is hardly stirring. Is this how you earn a PG-13?

The Hong Kong way

Righting Wrongs (1986).

While revising Planet Hong Kong for its web edition, I’ve been revisiting classic Hong Kong action scenes. In 1997-98, when the book was written, I had to rely on laserdiscs, but since then I’ve been able to look at more 35mm prints. (DVDs usually don’t help answer the sort of questions I’m asking, for reasons reviewed here.) Now I have a chance to put some thoughts about these movies online, in this blog and in the upcoming digital update of the book. As a start, here’s a recipe drawn from the best of Hong Kong fury.

First, go for clarity in every way. Not murky earth-toned sets but brightly colored and sharply lit ones; even an alley can dazzle. Put the camera on a tripod; pan if you must, but save your dolly moves for simple emphasis. No handheld.

Second, aim for precision. Stallone’s comments imply that a cameraman captures a preexisting fight, snatching an “interesting” shot here or there. But that’s not the case. Movie action is choreographed and the framing is calibrated to that. The gestures should be legible, favoring crisp and staccato movement, while the image’s composition aims to convey the action cleanly. It’s a pity that the haphazard framing of Stallone and his cameramen have ruined the choreography of Cory Yuen Kwai, Jet Li’s action designer (and a fine director in his own right).

Third, establish a rhythm. This involves not only building the fight. It also involves synchronizing the pace of characters’ movements with that of the cutting. On the whole, the old rule applies: More distant shots should be held longer than closer ones. This doesn’t mean you can’t use fast cutting, only that your fast cutting can be more finely judged when you take shot scale, composition, and speed of movement into account.

Rhythm means sensing a pulse, and for that you need slight pauses. So don’t cut away to something else before a punch or kick is completed. Let the arc of movement, itself perhaps stretched over several shots, come to a point of rest, if only for a couple of frames.

Fourth—and here is where realism is most explicitly abandoned—amplify the expressive qualities of the action. If movement is zigzag or springy or oscillating, stress that. Give emotional qualities not only to facial expressions but also to postures and combat moves. American heroes just grimace while their bodies remain inexpressive, lumpish. The hard guys in The Expendables might as well be made of granite. But in contrast your fighters needn’t wave their arms wildly. Just concentrate energy and emotion in the action. If the hero attacks, let him become as focused as a javelin. If your heroine falls, don’t let her just drop out of frame: Let her land with a thwack, preferably on the spine or neck, and let her body’s recoil send a spasm through the spectator too.

Hong Kong cinema supports Sergei Eisenstein’s belief that expressive human action is “infectious.” He thought that if physical action onscreen is imbued with vivid force it can arouse sympathetic echoes in the spectator’s own body. After a great action scene, such as in many Chang Cheh and Lau Kar-leung films of the 1970s, or in Yuen Kwai’s Righting Wrongs, when a tough guy gets a spittoon in the face, the viewer feels trembling and tired, but in a good way.

Glass story

Jackie Chan has become such a beaming, easygoing star that we forget that he was an excellent director of brutal fight scenes. He proved adept at filling anamorphic compositions with dynamic movement, as well as plucking out items of a set and sweeping them into the action. (See the parlor fight in Young Master, 1980, or the shenanigans in the rope factory in Miracles/ Mr. Canton and Lady Rose, 1989). In Police Story (1985), Jackie is trying to rescue Salina and save all the computer records in her briefcase. Koo’s gang is determined to stop him. The fight moves through different areas of a shopping mall.

In each of these locales, Jackie plays a suite of variations on what you can do with escalators, staircases, and, most memorably, glass. I can’t do justice to all the skirmishes, but consider some instances of how he stages and cuts the action for an impact that American movies seldom achieve.

The variations get steadily more elaborate. Early in the sequence, Jackie flings one thug, achingly, across the bottom handrails of an escalator.

The shot could hardly be more legible. You see everything. Next, Jackie is grabbed from the rear.

Naturally he has to flip his attacker down to the floor below, rendered in two dynamic shots from directly below and above.

Interestingly, the shots are so clearly composed (even with the fancy mirror effect in the second) that they can be very brief: 26 frames and 16 frames. Down at the bottom, the unfortunate fellow smashes through a display and lands straight on his spine. Unlike the security guards in Tomorrow Never Dies, this thug gets a little commiseration as he rolls over groaning. As in any fight sequences, disposable thugs may come back into action, but at least we’ll clearly see the fates of those who are put permanently out of commission.

After this burst of action Jackie provides a pause as he abruptly looks up in search of Salina.

What else can you do with escalators? How about tossing the next thug down the slim gap between two of them?

In a nice touch, we hear a long squeak as he slides down the trough.

Tomorrow Never Dies sets up its conveyor-belt climax straightforwardly, but Jackie’s choreography is more surprising. Audacious and imaginative as the stunts are, however, they are framed and cut in a way that makes the action clear and precise. Through cinematic choices Chan builds up an infectious arousal. This stuff hurts.

After a set-to in a hallway, Jackie pursues the gang into an area filled with display cases. He takes on the men ferociously, and sets them smashing through the vitrines in another string of variations. Jackie slams down a mirror on one thug, swings another into a display, and sends one spinning through a window. Each shot, of course, is of diagrammatic simplicity, all the better to amplify the expressive dimension and key up the viewer. You can’t watch shots of men hurled into layers of glass without feeling a few palpitations.

Nearly every shot is bound tightly to the next. What will occupy shot B is launched on the fringes of shot A, sometimes for only a few frames. The string of matches on action creates a fluid continuity quite different from the choppiness we often find in American sequences.

A good instance occurs after Jackie has been pinned under a toppled shelf. In a medium close-up, the gang leader orders his thug into action; behind him the plaid-coated thug moves left.

In long shot, with Jackie at a disadvantage, the thug continues his movement in the background as he grabs a heavy statuette.

In a medium-shot, Mr. Plaid Jacket lifts the statue, but as he moves aside he reveals Salina rushing toward him in the background. Look quick: She appears in the fifteenth frame, and is gone within another fifteen.

We can only glimpse Salina passing behind the thug, but the next shot shows her clearly: running, baseball bat in hand, toward him. The trajectory could not be clearer, and she swings the bat directly through the vitrine.

The force of the action is multiplied by the simplest cut possible: an axial enlargement, with the action slightly repeated and slowed. The first shot of Salina’s swing lasts seventeen frames, the second exactly twice as long. The arithmetic of the cutting extends the action’s beat.

Bursts of glass form the dominant, painful motif of this part of the sequence. (Jackie’s crew suggested he call the film Glass Story.) The shifting dynamic of the fight is rendered through close encounters of the splintery kind. But these are differentiated. Long shots portray the torments of the gang, but Jackie’s first encounter with glass is treated in one simple close shot, just a second long, that usually makes audiences flinch.

Jackie is attacked by the gang leader and he shoves Salina out of the way.

The leader springs forward to whack Jackie with the briefcase.

Cut to the opposite angle, a tight shot of Jackie.

The briefcase continues to be swung, and Jackie’s head smashes the windowpane.

Jackie bounces off the glass and grimaces in agony.

The proximity of the glass shards to his eyes probably triggers some primal revulsion in us, but this is only part of the image’s force. The whole shot lasts only 28 frames. I think that part of its percussive impact comes from the fact that at the start we don’t have time to register that the pane is there. (There are only seven frames before Jackie hits.) When the glass bursts, it’s as startling as if the screen surface has cracked as well, and this amplifies the painful impact of the blow.

For a time Jackie is at the gang’s mercy. But he makes a comeback, and eventually in a kind of summary of his other maneuvers he will bash the leader, body and head, through two glass cases. This phase of the scene concludes with Jackie running Mr. Plaid through a series of cases at the point of a motorcycle. Both crescendos are filmed in clear, smoothly-cut shots—and long shots at that.

We may wince for the fate of these gangsters, but we shuddered when we saw Jackie’s face knocked through a window. Soon Jackie will be flipping the leader down an escalator, a sort of envoi to the scene’s first phase, and he will be sliding down a three-story light pole to catch up with boss Koo himself.

To use Stallone’s comparison, I’d happily hang this splendid sequence in the Louvre.

But what sort of MPAA rating would it receive today? The painful physicality on display is given a staccato force through the framing and cutting. And don’t call it cartoonish. It’s Bond who’s cartoonish, with his unflappable ease and perfectly functioning gadgets and defiance of the laws of gravity and those fights he wins without suffering a scratch. Jackie shows us the sweat. He and his victims fall with painful awkwardness, he gets gashed and bruised, and he’s all too vulnerable to physics (or at least Hong Kong physics). Bond wins through debonair resourcefulness and a lot of luck. Jackie wins by refusing to lose.

He refuses to lose the audience too. In Police Story Jackie’s manic urge to make the scene maximally gripping is itself a little scary. Nonetheless, when a director isn’t afraid of tapping the real power of movies, a fight scene can give us an adrenalin transfusion. Who needs 3-D? Maybe only weak directors.

For other discussions of Hong Kong action scenes, see my “Aesthetics in Action: Kung-Fu, Gunplay, and Cinematic Expression” and “Richness through Imperfection: King Hu and the Glimpse” in Poetics of Cinema. There are some other examples in my online essay on Shaw Brothers. My most ambitious efforts in this direction are in Planet Hong Kong, where I take up the issue of rhythm in more detail than I can here. Alas, many contemporary Hong Kong action scenes have learned bad habits from Hollywood. I’ll talk about the decline of crisp fight staging in the new edition of PHK, due online in early December.

Todd McCarthy’s 1998 review of Armageddon is here. Peter DeBruge’s review of The Expendables is here. Both may lurk behind a paywall. The coverage of The Expendables I mention is Michael Goldman, “War Horses,” American Cinematographer 91, 9 (November 2010), 52-56. The pilot online issue is here.

The Dragon Dynasty version of Police Story includes Bey Logan’s conversation with Brett Ratner. During the commentary, Ratner notes that Jackie holds his shots longer than would an American director, who would be likely to cut on every punch. Incidentally, I’ve found many DD releases of Hong Kong films to be superior in quality to other DVD versions, and Logan’s commentaries are information-packed. His book Hong Kong Action Cinema remains a fine piece of work.

The images from Tomorrow Never Dies are taken from DVD, with all the drawbacks of that format for close analysis. But I don’t think my conclusions would vary if I worked from 35mm. The Police Story frames are analog frame enlargements from a 35mm print and allow accurate frame-by-frame analysis. Even then, Jackie’s pacing is so fast that blurring is inevitable. Thanks to Heather Heckman for her assistance in turning my slides into digital files.

PS 17 September 2010: I forgot to mention that Matt Zoller Seitz has provided two of the most discerning (and hilarious) critiques of the Michael Bay High Rococo Action Style, here and here.

Young Master.

Take it from a boomer: TV will break your heart

DB here:

Every so often someone will ask Kristin and me: “Why don’t you write about television?” This is usually followed by something like:

”You’re interested in narrative. The most exciting narrative experiments are going on in TV, not film.”

”You’re interested in visual experimentation. The most exciting developments in visuals are in TV.”

”TV is where the audience is.” Or “TV is where the culture is.”

”Film is borrowing a lot from TV, and producers and directors are crossing over.”

We might answer by saying we don’t watch any TV, but that would be a fib. Like everybody, we watch some TV. For us, it’s cable news commentary, The Simpsons, and Turner Classic Movies.

Truth be told, we have caught up with some programs on DVD. We watched the British and the US versions of The Office and enjoyed both (though the American version, no surprise, makes the characters more lovable). Kristin watched The Sopranos’ first season for a particular project. For similar purposes I watched and enjoyed Moonlighting and some Michael Mann TV material. Intrigued by the formal premise of 24, I dipped into the first season, but I found it visually so wretched I couldn’t continue. I got through four seasons of The Wire on DVD, largely because of the Pelecanos connection, but I found it over-hyped. It seemed to me a sturdy policeman’s-lot procedural, but rather fragmented and uninspiringly shot.

That’s it for the last three decades. No real-time monitoring of episodic TV (we haven’t seen Lost or Mad Men or the latest HBO sensations) and none of the reality shows or the music shows or even comedy like Colbert or Jon Stewart.

So we aren’t plugged in to the TV flow. Americans currently log over four and a half hours a day in front of the tube, so clearly we’re derelict in our duty. As Clay Shirky points out in Cognitive Surplus, TV viewing is Americans’ unpaid second job.

But why don’t I start following episodic TV? The answer is simple. I’ve been there. I was a TV kid before I was a film wonk. And I can assure you that watching TV leads to painful places—frustration, anger, sorrow. All you’re left with is nostalgia.

Commitment problems

I see the difference between films and TV shows this way. A movie demands little of you, a TV series demands a lot. Film asks only for casual interest, TV demands commitment. To follow a show week after week, even on a DVR, is to invest a large part of your life. Going to a movie demands three or four hours (travel time included).

Whether a movie is good or bad, at least it’s over pretty soon. If a TV show hooks you, prepare for many long-term ups and downs—weak episodes, strong ones, mediocre ones. Favorite actors leave or die, and replacements are seldom as good as the originals. A new character may be charming or annoying. An intriguing hero may accumulate distracting sidekicks. Plots take weird turns, sometimes dillydallying for months. All this can drag on for years.

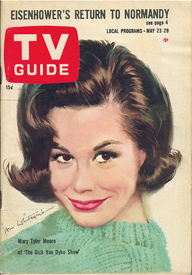

Of course TV-philes enjoy this slow samba. They point out, rightly, that living through the years along with the characters, watching them change in something like real time, brings them closer to us. Who doesn’t appreciate the way Mary Tyler Moore evolved into something like a feminist before America’s eyes? As early as 1952, the sagacious media critic Gilbert Seldes pointed out that intellectuals who thought that TV was plot-dependent were wrong.

It is natural that the actual plot of a single self-contained episode should be comparatively unimportant. . . . The very limitations of the style leads its creators to develop characters of considerable depth, to create dramatic conflict out of the interaction of people rather than out of an artificial juxtaposition of events. As television is a prime medium for transmitting character, this is all to the good (Writing for Television, pp. 115-116)

We get to know TV characters with an informal intimacy that is quite different from the way we relate to the somewhat outsize personalities that fill the movie screen. We learn TV characters’ pasts, their hobbies, their relations with kin, and all the other things that movies strip away unless they’re related to the plot’s through-line.

Having been lured by intriguing people more or less like us, you keep watching. Once you’re committed, however, there is trouble on the horizon. There are two possible outcomes. The series keeps up its quality and maintains your loyalty and offers you years of enjoyment. Then it is canceled. This is outrageous. You have lost some friends. Alternatively, the series declines in quality, and this makes you unhappy. You may drift away. Either way, your devotion has been spit upon.

It’s true that there is a third possibility. You might die before the series ends. How comforting is that?

With film you’re in and you’re out and you go on with your life. TV is like a long relationship that ends abruptly or wistfully. One way or another, TV will break your heart.

TV brat

Trust me, I’ve been there. Unlike most film nerds, I wasn’t a heavy moviegoer as a child. Living on a farm, I could get to movies only rarely. But my parents bought a TV quite early. So I grew up, if that’s the right phrase, on the box.

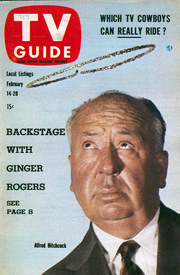

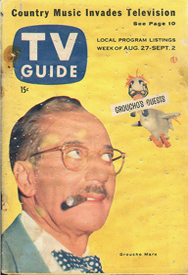

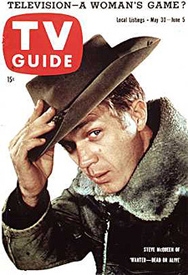

Childhood was spent with Howdy Doody (1947-1960) and Captain Video (1949-1955) and Your Hit Parade (1950-1959) and Jack Benny (1950-1965) and Burns and Allen (1950-1958) and Groucho (You Bet Your Life, 1950-1961) and Dragnet (1951-1959) and Disneyland (1954-2008) and The Mickey Mouse Club (1955-1959). With adolescence came Alfred Hitchcock Presents (1955-1965) and Maverick (1957-1962) and Ernie Kovacs (in syndication) and Naked City (1958-1963) and Hennesey (1959-1962) and The Twilight Zone (1959-1964) and Route 66 (1960-1964) and The Defenders (1961-1965) and East Side, West Side (1963-1964).

Some of the last few titles I’ve mentioned evoke particularly fond feelings in me. At a crucial phase of my life, they presented models of what the adult world might be.

For one thing, adults had an easy eloquence. Some of these shows seem overwritten by today’s standards, but actually they brought to television a sensitivity to language that seems rare in popular media now. Bret Maverick had a smooth line of patter, and even racketeers on Naked City could find the words. Dragnet‘s dialogue is remembered as absurdly laconic, but actually it showed that very short speeches could carry a thrill. At the other extreme were the soliloquys in Route 66. One that sticks in my mind came from a daughter, torn between love and exasperation, saying how touched she was when her father called one of her simpleton boyfriends “uncomplicated.” (The line was modeled on something said by Faulkner, I think.) I don’t recall characters insulting one another as much as they do nowadays, and of course obscenity and body humor were yet to come. At that point, TV relied so much on language that it might be considered illustrated radio.

Second, these shows made heroes of adults who were reflective and idealistic. They mused on social problems and thought their positions through. The father-son lawyers of The Defenders often disagreed about the moral choices their clients had made, and as a result you saw the different ways in which legal cases shaped people’s lives and public policy. Even a cop show like Naked City was less about fights and chases than it was about the causes, and costs, of crime.

Third, adults were empathic. This was partly, I suppose, because I was drawn to liberal TV; but I think it’s striking that my favorite dramatic shows showed professionals committed not to billable hours but to helping other people.

El segundo pueblo

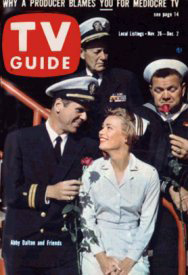

These qualities were epitomized in Hennesey. The continuing cast was small. Chick Hennesey (Jackie Cooper) is a navy doctor in his mid-thirties. His irascible superior Captain Shafer, is played by Roscoe Karns, bringer of dirty fun in 1930s and 1940s movies (“Shapely’s my name, shapely’s my game”). Nurse Martha Hale (Abby Dalton) serves as a romantic interest for Hennesey, and Max Bronski (Henry Kulky) is a dispensary assistant; both are vivid characters in their own right. A few others pop in occasionally, notably the rich eccentric dentist Harvey Spencer Blair III (played with eerie passivity by James Komack).

The series began as a situation comedy, but soon it became an early instance of the “dramedy”—the TV equivalent of sentimental comedy. In this classic genre, moderately grave problems cannot shake the essential concord of human relations. The tonal mixture makes a laugh track distracting; Hennesey‘s was eventually phased out.

The series was created and largely written by Don McGuire, who modeled his protagonist on a doctor he admired. Hennesey is l’homme moyen sensual, a man of no great ambitions or grand passions. He smokes cigarettes (Kent was a sponsor) but, surprisingly, doesn’t drink alcohol. He served in the army when very young (at Guadalcanal), went to UCLA medical school, and was drafted into the navy. Neither a career officer nor an ordinary doctor, he is more at home with enlisted men than the brass.

Hennesey isn’t a dramatic blank, but his virtues are quiet ones. He simply wants to help people get over the daily bumps in the road. He stammers when bullied by someone more aggressive, but sooner or later he quietly stands his ground. When he has a chance to do something decisive, he does it without fanfare. In the pilot episode, he has to override Shafer in order to extricate a man’s arm from a flywheel. But afterward he is likely to wonder whether he did the right thing. He often confesses his fears and weaknesses. Hennesey is a prototype, far in advance, of the caring, sharing male. He is, as Martha sometimes tells him, nice; but that sounds too soft. He is simply decent.

The plot often calls on him to confront people far more harsh and self-centered than he is. Often Captain Shafer, playing the narrative role of Arbitrary Lawgiver, assigns Henessey to unpleasant duties, like dealing with a lady psychologist who wants to find out why men join the navy. Often Henessey has to help men and women adjust to navy life, or to tell them that they are too unhealthy to continue. Sometimes he reminds arrogant doctors why they took up the calling. He also encounters civilians with problems that impinge on his own life. Going home to meet the doctor who inspired his career choice, he finds a bitter widower. In other episodes he simply observes someone else rising to the occasion. A bumbling helicopter pilot is a figure of fun until, behind the scenes, he risks his life to save a girl with appendicitis.

Everything about the series is modest: the level of the performances (only Shafer raises his voice), the accidents and digressions that deflect the plot, the cheap sets and recycled exterior shots, the jaunty hornpipe score that becomes an earworm on first hearing. But all these things enhance that TV-specific sense of a comfortable world with its familiar routines and unspoken bonds of teasing affection.

The show illustrates one of the virtues of TV of the time: talk. Characters emit single lines or even single words at a pace recalling that of the 1930s screwball comedies. Nurse Hale is the fastest, Shafer comes next, and Hennesey is left to play catch-up. In one episode, Shafer has just learned he’s going to be a grandfather, and he leaves the office euphoric. But Martha is a beat ahead.

Hennesey: I betcha this has him in a good mood for weeks.

Martha: For what?

Hennesey: For days.

Martha: Do you want to bet that within thirty seconds he’ll be in a bad mood?

Hennesey: No, that’s ridiculous.

Martha: Is it?

Hennesey: Of course. What could possibly get him upset in—?

Shafer returns, frowning.

Shafer: I just thought of something.

Martha: His first grandchild will be born overseas.

Shafer: Right.

Martha (to Chick): Think you’re playing with kids, huh?

The exchange, including blocking, takes nineteen seconds. It’s conventional, I suppose, but its brisk conviction modeled for one thirteen-year-old the possibility that adults are alert to each moment and enjoy rapid-fire sparring with their friends.

Harvey Spencer Blair III has more highfalutin rhetoric. In a 1961 episode, he declares his plan to run for mayor of San Diego.

Harvey: My election will see the rise of little people to positions of consequence, the molding of our future cultures, the era of a new world. Join with me, my dear, in crossing the New Frontier.

Martha: Leave the petition with me, Dr. Kennedy.

Harvey: I revel in the comparison.

Here even the double takes are modest. Characters react with a frown or a tilted chin or a widening of the eyes or a slight shake of the head. There can be verbal double-takes as well, mixed in with overlapping lines in the His Girl Friday/ Moonlighting manner. At the start of a 1961 episode, Martha enters the infirmary. Henessey is at the desk and Max is filing folders.

Without looking up, Chick says what he thinks Nurse Hale should say.

Hennesey: Morning, Max. Morning, doctor. Sorry I’m late.

Martha: I am not.

Hennesey (looking up): You’re not? It’s ten minutes after eight–

Martha (overlapping): I mean I’m not sorry. I have a very good excuse.

Hennesey: You had a run in your mascara?

Martha: I had to stop and talk to the senior nurse.

Max: Did you get it?

Martha: Yes.

Hennesey: Get what?

Max: Good, I’m glad.

Martha: Thank you, Max.

Hennesey: Get what?

Max: I bet it’ll be nice up there.

Martha: I hope so—

Hennesey (overlapping): Up where?

Max: If it isn’t too cold.

Hennesey: Oh, no, it can’t be too cold, it’s only cold up there in August—that is, if the winds from the equator don’t –Look, you two, don’t you think it’s only fair that if you discuss something in front of a third party, you might just—

Martha: A run in my mascara?

Nobody I knew talked like this, but why not talk like this? It would make life more lively. Backchat, I’ve learned over the years, can get you in trouble; life isn’t a TV show. But I still think that repartee, especially featuring stichomythia, is one of the pleasures of being a grownup. So too are the catchphrases we weave into our chitchat. The Hennesey tag I enjoyed was “El segundo pueblo,” uttered oracularly at a moment of crisis, and always translated with a different, incorrect meaning. My own life would feature motifs like “A meatloaf as big as the Ritz” (undergrad days), “Kitchen hot enough for you yet?” (grad school), and “If I’m gonna get shot at, I might as well get paid for it” (professorial years).

Being a film wonk, I can’t rewatch episodes without noting that those directed by McGuire have some flair. His staging fits the characters’ unassuming demeanor, providing a deft simplicity we don’t find in modern movies. This is doorknob cinema; scenes start when somebody enters a room. And people in the foreground respond to others coming in behind them.

The faster the gab, the slower the cutting, but extended takes can refresh the image by moving actors around. In one scene, Harvey, still planning to run for mayor, is slated for a court-martial. He enters to get the news. His somewhat zombified gait contrasts with Hennesey’s peppy, arm-swinging stride, usually on exhibit during the opening credits. (I learned things about grown-up walking styles too.)

As the shot goes on, Harvey gets the news he’s headed for the brig. Shafer and Hennesey gloat, but in the foreground, Martha suspects that Harvey’s got an ace up his sleeve.

When Harvey says he can’t attend his hearing, Martha lifts her cup: “Here comes the voodoo.”

Harvey reminds his colleagues that he’s due to be discharged from the service before the hearing date. The ensemble responds by regrouping, with Martha and Shafer trading places in the foreground and Hennesey slinking off.

When everybody has assumed a new position, Harvey volunteers to re-up, causing Shafer to shudder.

As Martha sits and Hennesey comes forward, Harvey produces some tickets for his campaign rally, at which Clifton Webb (yes, go figure) will be speaking. Interestingly, Jackie Cooper stays a bit out of sight, preparing for a later stage of the shot.

Harvey leaves, and Shafer’s attention turns to Hennesey as the person to be blamed.

Soon we are seeing characters moving in depth again as Martha gives a typical head-shake in the foreground.

The shot exploits principles of 1940s Hollywood depth staging, as did many of the filmed programs of the period. (The Defenders is particularly rich in this regard.) Simple and sharp, McGuire’s scene is more skilful than anything I saw yesterday in The Expendables.

Chick and Martha got married in the last episode of the series, in May of 1962. I would never see these people again, except in re-runs and syndication. In fact, all my favorite programs were cancelled during my high-school years. I set out for college in summer 1965, disabused of my love for TV. Ahead lay cinema, which would never betray me.

Of course watching a TV series on DVD changes the dynamic of week-in, week-out absorption; but the rhythm of real-time viewing seems to me one of TV’s artistic resources. Besides, wading through a whole series on DVD is still a hell of a commitment.

Gilbert Seldes’ Writing for Television is an original and imaginative study of conventions that still hold sway. He’s especially astute on how the differences in conditions of reception (film, public; TV, domestic) shape creative choices. Another entry on this site discusses Seldes as a critic of modern media.

On the idea that we are especially susceptible to popular culture in our early teens, see our earlier entry here.

Extensive collections of some of my favorite shows, like Reginald Rose’s The Defenders and David Susskind’s East Side, West Side are available for study in our Wisconsin Center for Film and Theater Research. Nat Hiken, a Milwaukee boy, also generously left us a cache of Bilkos and Car 54s.

Hennesey, once rerun on cable channels, has evidently never been published on DVD. Gray-market discs offer a few fugitive episodes, recycled from VHS, kept alive by others with an affection for the program. The most complete information I’ve found on the series is in David C. Tucker’s Lost Laughs of ’50s and ’60s Television: Thirty Sitcoms that Faded Off the Screen (McFarland, 2010), pp. 47-53. A list of episodes and broadcast dates is here.

For more on one staging technique that McGuire uses, you can visit our post on The Cross. See also Jim Emerson’s outstanding analysis of composition and cutting in Mad Men at scanners; the sequence he studies is reminiscent of mine. The best guide to analyzing TV technique is Jeremy Butler’s landmark Television Style.

George C. Scott in East Side, West Side. Stephen Bowie’s Classic TV History site provides a detailed study of this series.

PS 10 September 2010: Believe it or not, I hadn’t read A. O. Scott’s praise of current TV before I wrote this, but his thoughts develop the sort of ideas I mention at the start of this entry.

PPS 10 September 2010, later: Jason Mittell completely understood this entry. If you think that I’m saying TV isn’t worth studying , please read Jason’s careful piece. (In fact, you could count my discussion of Hennesey as an argument for studying TV!)

PPPS 11 September 2010: In my roll-call of TV that Kristin and I watched, how could I have forgotten our devotion to Twin Peaks (1990-1991)? I think I neglected to mention it because we didn’t consider of a piece with ordinary TV. We wanted to follow David Lynch’s career, and we considered the show an extension of his movies. Besides, the series showed the symptoms I diagnosed I mentioned above: episodes fluctuated in quality, and although I liked the later part of the second season better than many people did, its finale was a letdown for me too. For Kristin’s thoughts on Twin Peaks as TV’s equivalent to “art cinema,” see her Storytelling in Film and Television.

PPPPS 5 May 2011: Jackie Cooper died yesterday. The Times obituary glancingly mentions Hennesey, but ignores its real achievements.