Archive for October 2010

New Zealand is still Middle-earth: A summary of the Hobbit crisis

Richard Taylor during the October 20 anti-boycott march.

Kristin here:

Ordinarily I post about Peter Jackson’s Tolkien-adapted films on my other blog, The Frodo Franchise. But over the past five weeks a dramatic series of events has played out in New Zealand in regard to the Hobbit production. Those events tell us interesting things about today’s global filmmaking environment. As countries around the world create sophisticated filmmaking infrastructures, complete with post-production facilities, they are creating a competitive climate. Government agencies woo producers of big-budget films by offering tax rebates and other monetary and material incentives. Usually such negotiations go on behind closed doors, but the recent struggle over The Hobbit was played out more publicly.

Back in late September, the progress of Jackson’s project seemed slow. We Hobbit-watchers were mainly fretting over the lack of a greenlight for the two-part film “prequel” to The Lord of the Rings.

Of course, Tolkien’s LOTR (1954-55) was a sequel to The Hobbit (1937), but the films will have been made in reverse order. That’s due to MGM’s having the distribution rights back in 1995 when Peter Jackson went looking to use Tolkien’s novels to show off Weta Digital’s fancy new CGI abilities. Miramax bought the LOTR production and distribution rights and the Hobbit production rights.

Most of the news I was then blogging about related to MGM’s financial problems and how they would be resolved. Would Spyglass semi-merge with the ailing studio, convert its nearly $4 billion in debt into equity for its creditors, and bring it back into a position to uphold its half of the Hobbit co-production/co-distribution deal with New Line? Or would Carl Icahn push through his scheme to merge Lionsgate and MGM? The answer, by the way, came just this Friday, October 29, when the 100+ creditors voted to accept the Spyglass deal. I have been saying all along that the MGM situation was not the primary sticking point that was delaying the greenlight, even though most media reports and fan-site discussions assumed that it was. The greenlight having been given before this past week’s vote, I assume I was right. The real reason for the delay has not been revealed.

Meanwhile, other websites were speculating about casting rumors. Would Martin Freeman really play Bilbo, or were his other commitments going to interfere? (He will play Bilbo. Good choice, in my opinion. The man looks just like a hobbit.)

Then, on September 25 came the news that international actors’ unions were telling their members not to accept parts in The Hobbit. There was a boycott. The result was a maelstrom of events for the past five weeks or so. You may have heard about some of them. There were meetings and petitions. When Warner Bros. threatened to take the film to a different country, pro-Hobbit rallies followed. A visit by some high-up New Line and WB execs and lawyers to New Zealand led to hurried legislation to change the labor laws to reassure the studios that a strike wouldn’t happen. Finally, the government ended up raising the tax rebates for the production. Result: The Hobbit will be made in New Zealand after all. New Line, by the way, was folded into Warner Bros. by their parent company, Time Warner, after The Golden Compass failed at the box office. It remains a production unit but no longer does its own distribution, DVDs, etc.

The news that followed the launch of the boycott has come thick and fast, often involving misinformation. It was complicated, centering on an ambiguity in New Zealand labor laws as applied to actors and on a strange alliance between Kiwi and Australian unions. One of the biggest American film studios decided to use the occasion to demand more monetary incentives from the New Zealand government. I tried to keep up with all this and ended up posting 110 entries on the subject. (In this I was helped mightily by loyal readers who sent me links. Special thanks to eagle-eyed Paul Pereira.) That was out of 144 total entries from September 25 to now. There was plenty of other news to report. During all this, the MGM financial crisis was creeping toward its resolution, firm casting decisions were finally being announced, and the film finally got its greenlight. Whew!

For those who are interested in The Hobbit and the film industry in general but don’t want to slog through my blow-by-blow coverage, I’m offering a summary here, along with some thoughts on the implications of these events. Those who want the whole story can start with the link in the next paragraph and work your way forward. Obviously the links below don’t include all 110 entries.

In some cases the dates of my entries don’t mesh with those of the items I link to, given that New Zealand is one day ahead. I’ve indicated which side of the international dateline I’m talking about in cases where it matters.

September 25: Variety announces that the International Federation of Actors (an umbrella group of seven unions, including the Screen Actors Guild) is instructing its members not to accept roles in The Hobbit and to notify their union if they are offered one.

At that point, the film had not yet been greenlit, so it wasn’t clear how this would affect the production. The action against The Hobbit originated with the Australian union MEAA (Media Entertainment & Arts Alliance) and its director, Simon Whipp. Because relatively few actors in New Zealand are members of New Zealand Actors Equity, that small union is allied with the MEAA. The main goals of the union’s efforts were to secure residuals and job security for actors. The MEAA maintained that Ian McKellen (Gandalf), Cate Blanchett (Galadriel), and Hugo Weaving (Elrond) all supported the boycott; so far no evidence for this has been offered. Possibly they agreed to abide by it but were not in favor of it. Given the lack of a greenlight, none had been offered a role yet.

The main bone of contention has been a distinction made in labor laws in New Zealand. Actors are considered to be equivalent to contractors rather than employees, since they are hired on a temporary basis; it is illegal for a company to enter into negotiations with a union representing contractors. On that basis, Peter Jackson, who was first contacted in mid-August, refused to meet with the group. Besides, he isn’t the producer hiring the actors. Warner Bros., through New Line, is. As with all significant films, a separate production company, belonging to New Line, has been set up to make The Hobbit. It’s called 3 Foot 7. (The LOTR production company was 3 Foot 6, the average height of a hobbit being 3’6″.)

September 27. Peter Jackson responded angrily to the boycott, laying out the issues that would ultimately guide the New Zealand government’s response to the crisis:

“I can’t see beyond the ugly spectre of an Australian bully-boy using what he perceives as his weak Kiwi cousins to gain a foothold in this country’s film industry. They want greater  membership, since they get to increase their bank balance.

membership, since they get to increase their bank balance.

“I feel growing anger at the way this tiny minority is endangering a project that hundreds of people have worked on over the last two years, and the thousands about to be employed for the next four years, [and] the hundreds of millions of Warner Brothers dollars that is about to be spent in our economy.”

Losing The Hobbit would leave New Zealand “humiliated on the world stage” and “Warners would take a financial hit that would cause other studios to steer clear of New Zealand”, Jackson said.

“If The Hobbit goes east [East Europe in fact], look forward to a long, dry, big-budget movie drought in this country. We have done better in recent years with attracting overseas movies and the Australians would like a greater slice of the pie, which begins with them using The Hobbit to gain control of our film industry.”

Various people and organizations in New Zealand soon line up behind one side or the other. Those siding with Jackson include Film New Zealand (which promotes filmmaking by foreign countries in New Zealand) and SPADA (the Screen Production and Development Association) and eventually the government. On the unions’ side is the Council of Trade Unions.

September 28. New Line, Warner Bros., and MGM weigh in with a statement that ups the ante. It dismisses the MEAA’s claims as “baseless and unfair to Peter Jackson” and continues:

To classify the production as “non-union” is inaccurate. The cast and crew are being engaged under collective bargaining agreements where applicable and we are mindful of the rights of those individuals pursuant to those agreements. And while we have previously worked with MEAA, an Australian union now seeking to represent actors in New Zealand, the fact remains that there cannot be any collective bargaining with MEAA on this New Zealand production, for to do so would expose the production to liability and sanctions under New Zealand law. This legal prohibition has been explained to MEAA. We are disappointed that MEAA has nonetheless continued to pursue this course of action.

Motion picture production requires the certainty that a production can reasonably proceed without disruption and it is our general policy to avoid filming in locations where there is potential for work force uncertainty or other forms of instability. As such, we are exploring all alternative options in order to protect our business interests.

Thus the specter of the production being not only delayed but also taken to another country is raised, and the implications of such a threat will gradually force the government to take measures to prevent that happening.

Peter Jackson also makes a statement to the Wellington newspaper that the Hobbit production might move to Eastern Europe. (The next day he reveals that WB is considering six countries for it.)

That night, a group of 200 actors met in Auckland, issuing a statement again asking the producers to meet for negotiations.

October 1. Jackson and WB voluntarily offer a form of residuals to Hobbit actors:

Sir Peter Jackson said New Zealand actors who did not belong to the United States-based Screen Actors’ Guild had never before received residuals – a form of profit participation. Warner Brothers had agreed to provide money for New Zealand actors to share in the proceeds from the Hobbit films.

It would be worth “very real money” to New Zealand actors. “We are proud that it’s being introduced on our movie. The level of residuals is better than a similar scheme in Canada, and is much the same as the UK residual scheme. It is not quite as much as the SAG rate.”

After much speculation, an announcement is made that Peter Jackson will definitely direct the film (which Guillermo del Toro had exited in May).

At about this time members of the filmmaking community begin campaigning actively against the boycott. An anti-boycott petition for New Zealand filmmakers and persons indirectly related to production to sign goes online; it ends with 3275 people having endorsed it.

October 15. The Hobbit is greenlit, but the possibility of moving the production out of New Zealand remains. Actors who have already been auditioned begin to be officially cast.

October 20. Actors Equity NZ is due to meet in Wellington. Richard Taylor (head of Weta Workshop) calls for a protest march. The actors’ meeting is called off due, the union says, to the “angry mob” that results. (Videos and photos posted online show a lengthy line of people walking through the streets in a peaceful fashion; that’s Richard talking to the press in the photo at the top. A person less likely to incite a “mob” to anger I cannot imagine.) An actors’ meeting scheduled for the next day in Auckland is also called off, putatively for the same reason, though no protest event had been planned there.

The turning-point day

October 21 (NZ). Jackson and his partner Fran Walsh issue a statement that implies that Warner Bros. has decided to move The Hobbit elsewhere:

“Next week Warners are coming down to New Zealand to make arrangements to move the production offshore. It appears we cannot make films in our own country even when substantial financing is available.”

Helen Kelly, president of the Council of Trade Unions calls Jackson “a spoiled little brat” on national television, helping turn the public against her cause.

Fran Walsh hints during a radio interview that WB might move The Hobbit to Pinewood Studios in England (where the Harry Potter films have been shot).

Prime Minister John Key says he hopes the production can be kept in New Zealand. Economic Development Minister Gerry Brownlee says he will meet with the WB delegation.

The international actors’ boycott against The Hobbit is called off.

October 21 (U.S.)/22 (NZ). WB is still considering moving the production, saying it has no guarantee that the actors will not go on strike. Key suggests that the labor law might be changed to provide that guarantee. The proposed legislation soon will become known as the “Hobbit bill.”

The Wall Street Journal suggests that a slight slip in the value of the New Zealand dollars against the American dollar is partly due to uncertainties about whether The Hobbit production will stay in the country.

WB announces the casting of Martin Freeman as Bilbo, plus several actors chosen as dwarves.

Bilbo Baggins by Tolkien and Martin Freeman, Bilbo-to-be.

A “positive rally” to convince WB to keep the production in New Zealand is announced. This eventually results in individual rallies in several cities and towns on October 25.

( U.S. time) Variety reports that unnamed sources within WB have said the studio is inclining toward keeping the production in New Zealand. This is the only hint of positive news from inside WB that comes out during the entire process.

Over the next few days, much finger-pointing takes place. Figures concerning the potential loss to NZ tourism if the film goes elsewhere are released. Helen Kelly apologizes for her “brat” remark.

October 25 (NZ). The WB delegation of 10 executives and lawyers arrive in Wellington. The pro-Hobbit rallies take place.

Pro-Hobbit rally in Wellington (Marty Melville/Getty Images).

October 26. News breaks that if The Hobbit is sent to another country, the post-production work (originally intended for Weta Digital and Park Road Post, companies belonging to Jackson and his colleagues) could take place outside New Zealand.

The WB delegation arrives at the prime minister’s residence in a fleet of silver BMWs. After the meeting ends, Key puts the chances of retaining the production at 50-50. He reiterates that the labor law might be changed.

Photo: NZPA

Presumably at this meeting, WB also puts forward a demand for higher tax rebates or other incentives; other countries it has been considering have more generous terms. Ireland has offered 28%, while New Zealand’s Large Budget Screen Production Grant scheme offers only 15%. This demand is not made public until later. During Key’s speech after the meeting, however, he mentions the possibility of higher incentives, but says the government cannot match 28%.

Editorials soon appear attacking the idea of changing a law at the behest of a foreign company.

The government’s deal with Warner Bros.

October 27. The New Zealand dollar again slips in relation to the American dollar, again attributed to uncertainty about The Hobbit.

Key and other government officials meet again with the WB delegation. The legal problem has been resolved to both sides’ satisfaction, but WB is holding out for higher incentives.

In the evening, Key announces that an agreement has been reached and the Hobbit production will stay in New Zealand:

As part of the deal to keep production of the “The Hobbit” in New Zealand, the government will introduce new legislation on Thursday to clarify the difference between an employee and a contractor, Mr. Key said during a news conference in Wellington, adding that the change would affect only the film industry.

In addition, Mr. Key said the country would offset $10 million of Warner’s marketing costs as the government agreed to a joint venture with the studio to promote New Zealand “on the world stage.”

He also announced an additional tax rebate for the films, saying Warner Brothers would be eligible for as much as $7.5 million extra per picture, depending on the success of the films. New Zealand already offers a 15 percent rebate on money spent on the production of major movies.

(The figure for the government’s contribution to marketing costs is later given as $13 million.)

October 28 (NZ). Peter Jackson returns to work on pre-production, which his spokesperson says has been delayed by five weeks as a result of the boycott. Principal photography is expected to begin in February, 2011, as had been announced when the film was greenlit. (The two parts are due out in December 2012 and December 2013.)

The Stone Street Studios. The huge soundstage built after LOTR is at the left; the former headquarters of 3 Foot 6 at the upper left.

In Parliament, a vote to rush through consideration of the “Hobbit bill” passes, and debate continues until 10 pm.

October 29 (NZ). The “Hobbit bill” passes in Parliament by a vote of 66 to 50, thus fulfilling the governments offer to WB and ensuring that The Hobbit would stay in New Zealand. It was known in advance that Key had enough votes going into the debate to carry the legislation.

It is revealed that James Cameron has been in talks with Weta to make the two sequels to Avatar in New Zealand. (Avatar itself was partly shot in New Zealand, with the bulk of the special effects being done there.) The timing has nothing to do with the Hobbit-boycott crisis. The two films are due to follow The Hobbit, with releases in December 2014 and December 2015.

October 30 (NZ). It is announced that the Hobbiton set on a farm outside Matamata will be built as a permanent fixture to act as a tourist attraction. (The same set, used for LOTR, was dismantled after filming, leaving only blank white facades where the hobbit-holes had been; nevertheless the farm has attracted thousands of tourists. See below.) Warner Bros. had been persuaded by the New Zealand government to permit this, though whether this was part of the agreement made with the studio’s delegation is not clear. I suspect it was.

It is also announced that the extended coverage of the 15% tax rebates specified in the “Hobbit bill” will apply to other films from abroad made in New Zealand—but only those with budgets of $150 million or more. (Presumably in New Zealand dollars.)

A remarkable outcome

In a way, it is amazing that a film production, even a huge one like The Hobbit, virtually guaranteed to be a pair of hits, could influence the law of a country–and make the legal process happen so quickly. Yet given the ways countries and even states within the USA compete with each other to offer monetary incentives to film productions, in another way it is intriguing that such pressure is not exercised by powerful studios more often. In most cases, a production company simply weighs the advantages and chooses a country to shoot in. Maybe countries get into bidding wars to lure productions or maybe they just submit their proposals and hope for the best. Certainly the six other countries considered briefly by WB were quick to jump in with information about what they could offer the Hobbit production.

In the case of Warner Bros. and The Hobbit, everyone initially assumed that the two parts would be filmed in New Zealand, just as LOTR had been. Yet the actors’ unions created an opportunity. The boycott gave Warner Bros. the excuse to threaten to pull the film out of New Zealand. Meeting with top government officials, WB executives demanded assurance that a strike would not occur–and oh, by the way, we need higher monetary incentives. As a result, a compromise was reached, the incentives were expanded, and there was a happy ending for the many hundreds of filmmakers of various stripes who would otherwise have been out of work.

Although there is considerable bitterness among the actors’ union members and those who supported their efforts, many in New Zealand see the tactics of the MEAA as extremely misguided. Kiwi Jonathan King, the director of the comic horror film Black Sheep, sums it up:

But this was all precipitated by an equal or greater attack on our sovereignty: an aggressive action by an Australian-based union taken in the name of a number of our local actors, backed by the international acting unions (but not supported by a majority of NZ film workers), targeting The Hobbit, but with a view to establishing a ’standard’ contract across our whole industry. While the actors’ ambitions may be reasonable (though I’m not convinced they are in our tiny market and in these times of an embattled film business), the tactic of trying to leverage an attack on this huge production at its most precarious point to gain advantage over an entire industry was grotesquely cynical and heavy-handed, and, as I say, driven out of Australia. Imagine SAG dictating to Canadian producers how they may or may not make Canadian films!

Whether the deal was unwisely caused by a pushy Australian union is a matter for debate. Whether the New Zealand government unreasonably bowed down to a big American studio is as well. But the deal that the two parties reached is a remarkable one, perhaps indicative of the way the film industry works in this day of global filmmaking.

Warner Bros. gets more money and a more stable labor situation. What’s in it for New Zealand? First, the incentives for large-budget films from abroad to be made in the country are raised. This comes not through an increase in the tax-rebate rate but an expansion of what it covers:

The Government revealed this week that the new rules would mean up to $20 million in extra money for Warner Bros via tax rebates, on top of the estimated $50 million to $60 million under the old rules.

While the details of the Large Budget Screen Production Grant remain under wraps, Economic Development Minister Gerry Brownlee said it would effectively increase the incentives for large productions to come to New Zealand.

The grant is a 15 per cent tax rebate available on eligible domestic spending. At the moment a production could claim the rebate on screen development and pre-production spending, or post-production and visual effects spending, but not both.

If the Government allowed both aspects to be eligible, it would be a large carrot to dangle in front of movie studios.

Mr Brownlee was giving little away yesterday but said the broader rules would apply only to productions worth more than US$150 million ($200 million).

It would bridge the gap “in a small way” between what New Zealand offered and what other countries could offer.

During this period, it was claimed that WB had already spent around $100 million on pre-production on The Hobbit, which has been going on for well over a year now. That figure presumably is in New Zealand currency.

There are some in New Zealand who oppose “taxpayer dollars” going to Warner Bros. As has been pointed out–though apparently not absorbed by a lot of people–Warner Bros. will spend a lot of money in New Zealand and get some of it back. The money wouldn’t be in the government’s coffers if the film weren’t made in the country. It’s not tax-payers’ money that could somehow be spent on something else if the production went abroad.

Another advantage for the country is the permanent Hobbiton set, which will no doubt increase tourism. There are fans who have already taken two or three tours of LOTR locations and will no doubt start saving up to take another.

One item that didn’t get noticed much during the deluge of news is that one of the two parts will have its world premiere in New Zealand. That’ll probably happen in the wonderful and historic Embassy theater, which was refurbished for the world premiere of The Return of the King. It was estimated that the influx of tourists and journalists for that event brought NZ$7 million to the city of Wellington. About $25 million in free publicity was provided by the international media coverage.

The Embassy in October 2003, being prepared for the Return of the King world premiere.

The deal also essentially makes the government of New Zealand into a brand partner with New Line to provide mutual publicity for The Hobbit. As I describe in Chapter 10 of The Frodo Franchise, the government used LOTR to “rebrand” the entire country. It worked spectacularly well and had a ripple effect through many sectors of society outside filmmaking. The country came to be known more for its beauty, its creativity, and its technical innovations than for its 40 million sheep. Now in the deal over The Hobbit, the government has committed to providing NZ$13 million for WB’s publicity campaign. But the money will also go to draw business and tourists. As TVNZ reported:

But the Prime Minister says for the other $13 million in marketing subsidies, the country’s tourism industry gets plenty in return.

“Warner Brothers has never done this before so they were reluctant participants, but we argued strongly,” Key said.

Every DVD and download of The Hobbit will also feature a Jackson-directed video promoting New Zealand as a tourist and filmmaking destination.

Graeme Mason of the New Zealand Film Commission says the promotional video will be invaluable.

“As someone who’s worked internationally for most of my life, you can’t quantify how much that is worth. That’s advertising you simply could not buy.”

If the first Hobbit film is as popular as the last Lord of the Rings movie, the promotional video could feature on 50 million DVDs.

Suzanne Carter of Tourism New Zealand agrees having The Hobbit production here is a dream come true.

“The opportunity to showcase New Zealand internationally both on the screen and now in living rooms around the world is a dream come true,” Carter said.

Marketing expert Paul Sinclair says the $13 million subsidy works out at 26 cents a DVD.

“It’s a bargain. It is gold literally for New Zealand, for brand New Zealand,” he said.

It’s not clear how the promotional partnership will be handled. There was a similar, if smaller partnership when LOTR was made. New Line permitted Investment New Zealand, Tourism New Zealand, the New Zealand Film Commission, and Film New Zealand to use the phrase, “New Zealand, Home of Middle-earth” without paying a licensing fee. (Air New Zealand was an actual brand partner during the LOTR years.) But for the government to actually underwrite the studio’s promotional campaign may entail more. That deal is more like the traditional brand partnership, where the partner agrees to pay for a certain amount of publicity costs in exchange for the right to use motifs from the film in its advertising. Has a whole country ever brand-partnered a film? I can’t think of one.

In my book I wrote that LOTR “can fairly claim to be one of the most historically significant films ever made.” That’s partly why I wrote the book, to trace its influences in almost every aspect of film making, marketing, and merchandising–as well as its impact on the tiny New Zealand film industry that existed before the trilogy came there. Years later, I still think that my claim about the trilogy’s influences was right. When an obscure art film from Chile or Iran carries a credit for digital color grading, it shows that the procedure, pioneered for LOTR, has become nearly ubiquitous. There are many other examples. The troubled lead-up to The Hobbit‘s production and the solutions found to its problems suggest that it will carry on in its predecessor’s fashion, having long-term consequences beyond boosting Warner Bros.’ bottom line. It will be interesting to see if other big studios announce they will film in one country and then find ways of maneuvering better terms by threatening to leave–or by actually leaving.

From Worldwide Hippies

More revelations of film history on DVD

The Great Consoler.

Kristin here:

Upon returning from Vancouver, we found the usual mountain of mail awaiting us. Among the bills and ads were some very welcome items: a new flock of DVDs of considerable historical interest.

A German Documentary on Veit Harlan

After Leni Reifenstahl, Veit Harlan is the most famous of the directors who made films for the Nazi regime. He made Jud Süss, which is the only non-Riefenstahl Nazi film you might have seen apart from Triumph of the Will and (if you think it’s Nazi propaganda) Olympia.

Now Felix Moeller has made a documentary film, Harlan: Im Schatten von Jud Süss (“In the Shadow of Jud Süss,” c. 100 minutes). It’s available on a German DVD from Edition Salzgeber and can be purchased from Amazon Germany. (Beware, it’s coded Region 2, so you’ll need a multi-region player.) It has English subtitles, a feature some European DVD makers wisely include, since they know that there are a lot of us out here with multi-regional players. A region 1 version will also be released in the U.S. on November 23 and is available for pre-orders on Amazon.

Harlan is a fascinating film, both in terms of its subject matter and its strategies. It starts out in a fairly conventional way, showing Harlan’s grave, and then drops a few brief clips from Jud Süss in among shots introducing some of the director’s descendants. He was married twice and had five children, who in turn had children, and there are nephews and nieces as well. At one point one granddaughter draws a family tree to help us out. (The small accompanying booklet has a “who’s who” feature with photos to help us keep the family members straight. This booklet is entirely in German.)

Much of the early part of the film is taken up with the story of Harlan’s career making films for the Nazis, being found innocent after two trials in the post-war era, and continuing his filmmaking into the 1950s. A nicely ironic comparison is made between Harlan’s “I was just following orders” defense and the identical defense that Süss makes during his trial scene in the film.

Initially the relatives seem to be present in part to provide information and in part to comment on Harlan’s life. Later in the film, however, we realize that “the shadow of Jud Süss” falls over them as well, and they have reacted in a wide variety of ways. A expository motif that runs through the film is a visit paid by several of the younger family members to an exhibition on the film (see below), where they (and we) are shown documents and clips.

One son, Thomas, denounced his father publicly and for decades sought evidence to convict Nazi war criminals. (Thomas Harlan died last weekend; see David Hudson’s obituary here.) Kristian Harlan and Maria Körber, his half-brother and half-sister, criticize him for not keeping his attitudes toward his father in the family. Thomas’ daughter Alice works as a physiotherapist in Paris and realizes she does not share her grandfather’s guilt–yet she worries about some sort inherited taint. Another son, Caspar, became an anti-nuclear activist, along with his wife and three daughters. Two sisters, Maria Körber and Susanne Körber both married Jews, almost as if to make amends for their father’s implicit role in the extermination of these men’s families; neither marriage ended well. A niece, Christiane, married Stanley Kubrick, who as a Jew was both shocked and fascinated by her relationship to Veit Harlan; he at one point planned to make a film on the Nazi director. Christiane’s brother ended up producing some of Kubrick’s films.

One thing that struck me was the generational difference in the attitudes toward Jud Süss itself. The first generation of sons, daughters, nieces, and nephews find it powerful, reprehensible, and disturbing. One of the granddaughters, however, considers it “so cheesy, and really banal, too,” wondering how anyone in the 1940s could have taken it seriously. This seems to reflect an attitude that many young people have toward old films;  she might be just as dismissive of a classic John Ford film of the same era. It’s a good argument in favor of teaching students about the conventions of older films and helping them to watch them with more respect. Not knowing at least a little about the historical context could easily make younger generations not take the propaganda of the past any more seriously than they take the entertainment films of Hollywood in the 1930s and 1940s. (One can’t fault the granddaughter too much; she belongs to the family of anti-nuclear activists.)

she might be just as dismissive of a classic John Ford film of the same era. It’s a good argument in favor of teaching students about the conventions of older films and helping them to watch them with more respect. Not knowing at least a little about the historical context could easily make younger generations not take the propaganda of the past any more seriously than they take the entertainment films of Hollywood in the 1930s and 1940s. (One can’t fault the granddaughter too much; she belongs to the family of anti-nuclear activists.)

The filmmakers had extensive access to good prints of several of Harlan’s major films. One, Der Herrscher (“The Master,” 1937), deals with a factory whose owner is a strong leader type. The frame at left shows off Harlan’s feel for crowds that made him the equivalent for fiction film to Leni Riefenstahl as a documentarist. (Indeed, one might suspect a bit of influence here.) There are also home movies, some taken behind the scenes during the filming of Harlan’s Nazi-era films. Munich archivist Stefan Drössler adds some historical perspective. The exhibition shown in the film provides glimpses of key documents.

Harlan could be quite useful in the classroom. Obviously courses on German history would benefit from it. Film history classes could show it in a unit on Nazi cinema, either in combination with or as a replacement for Jud Süss or one of the other major Nazi film. But it also gives an interesting perspective on the post-war decades and the ways in which guilt and expiation could linger across generations.

Thanks to my friend Marianne Eaton-Krauss for recommending this film to me!

[Added October 31: Critic Kent Jones has kindly written to point out that Felix Moeller is Margarethe Von Trotta’s son. Kent has written a piece on Veit and Thomas Harlan in the May/June 2010 issue of Film Comment.]

The launch of a Russian DVD series

The Russian Cinema Council (RUSICICO) has recently released the first five DVDs in its new “Academia” series. The first group comes from the Soviet silent and early sound era: Strike, October, Happiness, The Great Consoler, and Engineer Prite’s Project. They can easily be ordered on the company’s website. Googling will find a few smaller online companies in Europe that sell them, but they are not available (yet, at least) from the larger sites like Amazon.

[January 31, 2012: Hyperkino has announced that its DVDs can now be purchased at a British site, MovieMail. For more on Hyperkino, see here.]

A major feature of these discs is “Hyperkino,” a version in which numbers appear at intervals in the upper right; clicking on them summons up an explanatory text. For Strike, for example, one can read an explanation of the “Collective of the 1st Works’ Theater” when that phrase appears in the credits. (The complete text of the annotations for Engineer Prite’s Project have been printed as an article in Studies in Russian and Soviet Cinema [Vol. 4, no. 1, 2010].) These “footnotes” would be of interest to film students, mainly at the graduate level; they would be invaluable for lecture preparation. The Hyperkino version appears on the first disc of each two-disc set; the film without the feature appears on the other disc. Despite the fact that the text on the boxes are almost entirely in Russian, the films have optional subtitles in English, French, Spanish, Italian, German, and Portuguese; the Hyperkino notes are available only in Russian or English. The discs have no region coding.

A major feature of these discs is “Hyperkino,” a version in which numbers appear at intervals in the upper right; clicking on them summons up an explanatory text. For Strike, for example, one can read an explanation of the “Collective of the 1st Works’ Theater” when that phrase appears in the credits. (The complete text of the annotations for Engineer Prite’s Project have been printed as an article in Studies in Russian and Soviet Cinema [Vol. 4, no. 1, 2010].) These “footnotes” would be of interest to film students, mainly at the graduate level; they would be invaluable for lecture preparation. The Hyperkino version appears on the first disc of each two-disc set; the film without the feature appears on the other disc. Despite the fact that the text on the boxes are almost entirely in Russian, the films have optional subtitles in English, French, Spanish, Italian, German, and Portuguese; the Hyperkino notes are available only in Russian or English. The discs have no region coding.

The prints of Strike and October are both the familiar step-printed versions. The visual quality is reasonably good.

(We did not purchase the Happiness disc, since the film had already been available in DVD and we’re not Medvedkin specialists.)

The most important contribution of the series so far has been to make two rare Kuleshov titles available to the general public for the first time. Engineer Prite’s Project was his first film. Previously it was available in archives in a print lacking intertitles. The story was so difficult to follow that the film seemed to be incomplete. Now, with the intertitles reconstructed and inserted into the film, it makes sense. It’s a short feature about industrial intrigue, notable in its mixture of traditional European tableau staging style and some sophisticated American-style editing that was a complete innovation for Russian cinema. The release of Engineer Prite’s Project on DVD fills a large gap in the history of the Soviet silent cinema, since it was the first film by one of the group that would form the Montage movement. Indeed, the fast cutting in a brief fight scene looks forward to that movement:

The DVD also includes a documentary, The Kuleshov Effect, made in 1969. It’s a helpful overview, with clips from the major films up to The Great Consoler, along with interviews with Kuleshov, scenarist and Russian Formalist critic Viktor Shklovski, and others. It’s just under an hour and would be a great teaching tool for a history or theory class.

If Engineer Prite’s Project is of interest mainly for its historical significance, The Great Consoler is perhaps Kuleshov’s masterpiece. The complex, multi-leveled narratives so popular in contemporary cinema have nothing on this film’s storytelling. It shifts among three levels with thematic parallels. In one, an abused, miserable shop girl (played by Alexandra Khokhlova, Kuleshov’s wife and leading proponent of the “biomechanical” school of acting) reads O. Henry short stories as escapism. In another, O. Henry himself is seen in prison (as he was in real life). In a third, we see a dramatization of his tale of convict Jimmy Valentine (“A Retrieved Reformation”). Each level is filmed in a slightly different style, and the moralistic lesson–those who suffer from exploitation under capitalism find only hollow consolation in popular culture–is somewhat undercut by the zestful stylization with which Kuleshov presents the sentimental tale of Valentine.

Chaplin (Slowly) Becomes The Little Tramp

On October 26, Flicker Alley is coming out with another of its big boxes of restored films. (Amazon has it available for pre-order.) This time it’s four discs containing a group of 34 of Charlie Chaplin’s Keystone-era films (of the 35 he made there). The press release describes the lengthy process of finding and restoring prints, which involved several archives:

With the support of Association Chaplin (Paris), 35mm full aperture, early-generation materials were gathered over an eight year search on almost all the films from archives and collectors  around the world, and were painstakingly piece together and restored by the British Film Institute National Archive, the Cineteca di Bologna and its laboratory L’Immagine Ritrovata in Italy, and Lobsters Films in Paris. Most are now clear, sharp and rock-steady, although some reveal that their source prints are well-used and a handful survive only in 16mm.

around the world, and were painstakingly piece together and restored by the British Film Institute National Archive, the Cineteca di Bologna and its laboratory L’Immagine Ritrovata in Italy, and Lobsters Films in Paris. Most are now clear, sharp and rock-steady, although some reveal that their source prints are well-used and a handful survive only in 16mm.

The earlier films in the set remind us that Chaplin began as a player in films where Mabel Normand was the star attraction (and she directed them herself). He didn’t always wear his “Little Tramp” outfit, either. Such films as The Property Man, The Rounders (co-starring Fatty Arbuckle), and Tillie’s Punctured Romance (restored by the UCLA archive) are included. A trim little booklet by Jeffrey Vance includes historical background and program notes. Original musical accompaniment is provided by Neil Brand, Robert Israel, and others. On-disc bonus materials include a documentary, “Inside the Keystone Project” and a couple of Chaplin-related silent films from the era, including a cartoon featuring him as a character.

Chaplin devised his “Little Tramp” outfit during this early era, though he didn’t use it in every Keystone film. He wasn’t yet the poignant figure of the later 1910s and 1920s. In Mabel at the Wheel, for example, he’s a pugnacious, bomb-wielding villain, with Mabel Normand, who directed the film, in the lead. (At left above, he belatedly  discovers that Mabel is no longer seated behind him on the motorcycle.) Chaplin buffs will have a field day with this set. The clarity makes it easier to spot the many comics who play bit roles here. Mack Swain wanders through, Mack Sennett has a small role as a yokel, and one can see a very young Edgar Kennedy seated behind Chaplin in the bleachers (right).

discovers that Mabel is no longer seated behind him on the motorcycle.) Chaplin buffs will have a field day with this set. The clarity makes it easier to spot the many comics who play bit roles here. Mack Swain wanders through, Mack Sennett has a small role as a yokel, and one can see a very young Edgar Kennedy seated behind Chaplin in the bleachers (right).

Each film is preceded by a title card that specifies the source material for the restoration, as well as the archives and other institutions involved. Mabel at the Wheel, for example, was assembled from four nitrate prints held by various collections. As the frames here indicate, it’s generally very clear and undamaged, though occasionally a shot from a more worn print appears.

We often complain about seeing films for the first time on DVD when they were meant to be seen on celluloid projected on the big screen. But for rare silent films like these Chaplin shorts, DVD replaces the old 8mm and 16mm prints that I remember from my graduate-school days in the 1970s. Our friend and colleague Frank Scheide, who was writing his dissertation on Chaplin’s music-hall background, would present programs of such prints in his home, but there were items that remained elusive. (Frank has co-edited two anthologies on Chaplin’s later films; see here and here.) Now we’re lucky enough to have archives restoring films in part to make available in the new format. Most of these images are far better quality than 8mm or even 16mm could render.

As with the giant Georges Méliès boxed set released in 2008, the new Chaplin discs make it easy to go through his career in strict chronological order, either as the films were made or as they were released (often not the same thing in those early days). The set is a vital item for collections of silent films and will no doubt feature among the nominees in the DVD awardsfor next year’s Bologna festival, Il Cinema Ritrovato. Three Hyperkino titles were among last year’s winners.

Mark your calendars!

On November 7, Turner Classic Movies will be showing the new restoration of Metropolis (8 pm Eastern time), followed by a one-hour documentary Metropolis Refound (11 pm Eastern time), on the discovery of a nearly complete print in An Argentinean archive. On November 4, the restored Pandora and the Flying Dutchman (1951; starts at 10 pm Eastern time) will be shown. It’s by the little-known auteur Albert Lewin; if you love Powell and Pressburger movies, you’ll probably love this film. Every Monday from November 1 to December 13, TCM will air its original series, Moguls & Movie Stars (8 pm Eastern time). Each episode will be followed by several films of the era discussed. One highlight not to be missed is Lois Weber’s wonderful 1921 feature, The Blot. It’s probably the only film ever made about the low pay of university professors, but its real strength is in the character study of haves and have-nots living next door to each other. Back when I taught a history of silent cinema class at the University of Iowa in 1980/81, this was one of the films I showed to demonstrate that silent films weren’t as simple and naive as young people today might assume. (The other was King Vidor’s 1924 Wine of Youth.) Set your recorders, since The Blot airs at 4:45 am EST on November 8. For more highlights, keep checking the TCM website, which hasn’t yet posted its November schedule.

Harlan: Im Shatten von Jud Süss

Vancouver: Final freeze-frames

DB here:

This slide, which appeared briefly before every screening at the Vancouver International Film Festival, epitomizes one of the event’s virtues: quiet sanity. Of course we must discourage people from recording the movie. But just as surely, we want people to photograph the filmmakers and record their comments and get the word out. Spreading the news benefits everybody, particularly the filmmakers.

Indeed, the whole VIFF clambake is run as efficiently as anyone can imagine. Want to get into a film? Very likely you will. A movie is getting buzz? Likely as not, extra screenings will be mounted. Annoyed by mobile devices in the throngs around you? House managers firmly ask people to shut them off. Now. Yet there’s nothing aggressive here. This is a city in which the buses preface the flashing notice “Out of Service” with an apologetic “Sorry.” A Manhattan bus would say, “You’re outta luck, pal.”

Now that Kristin and I are back, we know whom to thank: the organizers, the programmers, the office staff, and the inexhaustibly cheerful volunteers (700 strong). Below are Alan Franey, Festival Director, and PoChu AuYeung, Program Manager and Senior Programmer.

Come down for breakfast and you’re likely to run into Foreign Guest Coordinator Theresa Ho and Hospitality Suite Manager Eunhee Cha Brown. Dreyfus is usually not far away.

Then there’s the multi-talented Lillooet Fox, Food and Beverage Coordinator, waffle wrangler, and music supervisor for Amazon Falls, playing in the festival.

Ever notice how film people are always “on,” always subtly copping stances and looks from movies? Shelly Kraicer, Dragons & Tigers programmer, does his dressed-down version of Lars von Trier.

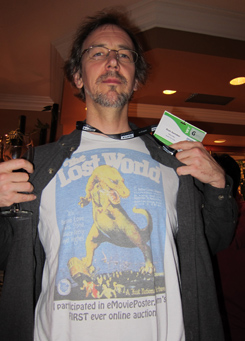

Speaking of T-shirts, nothing beats telling a story with your thorax. Consider Sean Axmaker (Parallax View) and Robert Koehler (Anaheim International Film Festival) and Raymond Phathanavirangoon (Hong Kong International Film Festival).

At happy hour, the waffles vanish and adult beverages come into their own. VIFF programmer and editor of Cinema Scope Mark Peranson hoists one with Variety critic (and University of Wisconsin alum) Rob Nelson.

Of course everyone mingles with filmmakers. Freddie Wong, director of The Drunkard, is reunited with Bérénice Reynaud, Cal Arts professor and author of a book on City of Sadness.

Tony Rayns, veteran Dragons and Tigers programmer, is flanked by Bong Joon-ho on the left, Denis Côté (Curling) across the table, and Mark Peranson on the right. Geoff Gardner and Jack Vermee are in the distance. Again, the cinephiles pay homage to a shot, in this case from Hong Sangsoo’s Oki’s Movie.

Jim Udden, another Badger and Professor at Gettysburg College (and author of a book on Hou Hsiao-hsien), talks Taiwanese film with director David Verbeek (R U There?).

Trustworthy translator Alex Fu and director Zhu Wen (Thomas Mao).

Takahashi Nazuki and Abe Saori celebrate after their screening of Icarus Under the Sun.

Meanwhile, Geoff Gardner (watch for his VIFF coverage in Urban Cinefile) finds that a rival venue has conjured up a star from another era.

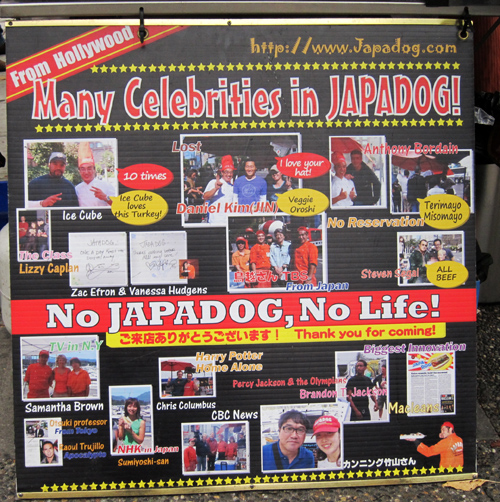

And although we left Vancouver all too soon, we’ll always have Japadog. Not everything in Vancouver is quiet sanity, but even the nuttiness is quite easygoing.

I recommend no. 4, Spicy Cheese Terimayo.

A last celluloid banquet from Vancouver

Detail from “Crimson Autumn” (1931) by Ural Tansykbaev (from The Desert of Forbidden Art)

Kristin here:

A Film Unfinished (Israel; dir. Yael Hersonski, 2010)

A Film Unfinished satisfies on many levels. It is based on several reels of an unfinished Nazi propaganda film labeled “The Ghetto,” discovered among an archive of thousands of cans of Nazi footage. On a simple documentary level, the scenes in the film show precious evidence of life in the Warsaw ghetto in the 1941-42 era, before most of its inhabitants were sent to death camps. As a piece of historical research on the part of the filmmakers, who found written and taped material that shed considerable light on this mysterious footage, it  comes across as a tightly constructed detective story. For theorists of documentary who want to stress that no non-fiction films can reveal life as it is, without manipulation, A Film Unfinished provides a dramatic example.

comes across as a tightly constructed detective story. For theorists of documentary who want to stress that no non-fiction films can reveal life as it is, without manipulation, A Film Unfinished provides a dramatic example.

The samples from the silent footage shown early in A Film Unfinished show a strange combination of subject matter. Apparently candid footage of people in the street, going about their daily lives, is mixed in with scenes of well-dressed men and women in restaurants or elegant apartments. How do these incongruous scenes fit together?

The filmmakers found extensive diaries kept by one of the officials in charge of the Ghetto, as well as taped testimony given in 1961 by one of the main cameramen who recorded the footage. Passages from these, read over additional footage from the film,gradually reveal at least part of the purpose behind the footage. The Nazis apparently wanted to show that some inhabitants of the ghetto were living a normal, even luxurious life (above left). But other scenes were shot showing these same people on sidewalks. Beggars pass by them, but the actors playing the well-off Jews were instructed to ignore them. The result would  presumably have been a display of Jews not only living well but also indifferent to the fates of their less fortunate neighbors.

presumably have been a display of Jews not only living well but also indifferent to the fates of their less fortunate neighbors.

The filmmaking process frequently intrudes. Apart from the voiceover readings from witnesses to the filming, there are occasional glimpses of cameramen in the backgrounds of scenes (left). Moreover, one reel of the rediscovered film turned out to be unedited takes of several brief sequences, showing retakes of the same footage. Thus an apparently candid shot of two little boys looking into a shop window abundantly stocked with food turns out to have been staged; we even get a glimpse of one of the filmmakers leaning into the shot to direct the boys. A scene of police clearing a crowded street was done by assembling a large group of Jews and then having the police drive people away (the scene at left being part of that action). Urgency was added when the filmmakers fired shots into the air to frighten the crowd.

An added layer was given to A Film Unfinished by assembling a small group of men and women from the ghetto who witnessed many of the events. They are seen watching the film and adding comments. One remembers having seen the filming. Another worries that she will see someone she once knew among the faces on the screen. The presence of these witnesses emphasizes the fact that what we are watching in the rediscovered footage is both an elaborately staged series of events and a grim record of reality in the ghetto. A particularly grim sequence shows men with a handcart gathering corpses from the sidewalks (where helpless relatives, without any other recourse, dumped them overnight). These are taken to a mass grave, where they are stacked like firewood, covered with sheets of paper, and buried. Though the men working at this grisly task were clearly told what to do by the filmmakers, the fact remains that this gathering and disposing of bodies was a routine that went on daily in the late days of the ghetto.

A Film Unfinished would be very useful in a class on documentary cinema.

The Desert of Forbidden Art (Russian/USA/Uzbekistan; dir. Tchavdar Gorgiev and Amanda Pope, 2010)

Our interest in 1920s and 1930s Soviet avant-garde art led David and me to this film. It reveals the remarkable, unknown work of Igor Savitsky, a Russian Russian archaeologist who discovered the culture and art of the Karakalpakstan region of Uzbekistan. Applying for government funds to create the Karakalpak Museum of Arts, Savitsky initially stocked it with the jewelry, costumes, pottery, and other local cultural artifacts that were discouraged by the Soviet modernization policy.

He also discovered that there were many hidden paintings and drawings by artists whose avant-garde tendencies had gotten them into trouble with the central Soviet government in the Stalinist era. In 1966 he secretly–and very illegally–began using government money to buy up whole caches of these works. By the time of his death in 1984, he had acquired around 44,000 of them! Many are still in storage, awaiting restoration, but the galleries of this remote museum are full of extraordinary, hitherto unknown artworks.

The Desert of Forbidden Art is informative not only about the history of Savitsky and the museum, but it reveals something of the current culture of this isolated province, a culture which figures prominently in the artworks as well. Sons and daughters of the artists appear on camera, as does Marinika Babanarzorova, the museum’s current director. Naturally many beautiful artworks are on display as well.

The film touches only briefly on the fact that these artworks have been hidden away in a remote desert area which is also increasingly under the sway of Islamic extremism. A few documentary shots show the dynamiting of ancient rock-cut Buddha statues in adjacent Afghanistan in 2001. The head of the Nukus Museum was invited to appear with the film at the VIFF, but she was unable to get permission to leave the country. One is left wondering whether these artworks will need to be rescued anew.

The film is screening widely at film festivals and societies, mostly in the USA but in a few other countries as well. See its website for a schedule of upcoming showings. It also will be run in April or May, 2011 in the PBS series “Independent Lens.”

Certified Copy (France/Italy/Belgium; dir. Abbas Kiarostami, 2010)

This was the film I was most looking forward to at the festival, and it was the last–and best–one I saw. As usual, Kiarostami has come up with a novel approach to storytelling. (See David’s entry on Shirin.) After only one viewing, I’m not confident enough to say much about Certified Copy. Besides, almost anything I say about the plot will give away too much. This is a puzzle film that unfolds very slowly and very subtly.

It seems to work in ways almost opposite to those of the big puzzle film of the year, Inception. That film was almost all exposition, which we had to frantically note and try to piece together to get even a rough grasp of the plot. Certified Copy has almost no exposition–or none that we can recognize immediately or even trust when we do recognize it. I could gauge how slowly that recognition comes by the fact that the laughter at apparently incongruous behavior between the characters gradually faded. Different members of the audience realized at different moments that what had seemed incongruous maybe wasn’t after all, though it’s possible that the incongruity was just increasing right up to the end. Close to the end, only a lady two rows behind me was still laughing.

Essentially what happens is that a plot unfolds, and despite a lack of solid information, most of us probably infer from the conversations enough to assume we understand the two main characters and their relationship. Eventually their actions suggest that perhaps an entirely different plot and relationship has been unfolding all along. (This comes fairly late in the film, in maybe the last third or even quarter.) Perhaps the information we receive does not allow us to decide in this ambiguous situation, though I think people do tend to decide. I decided one way, David decided the other.

Interestingly, this mirrors in longer form the last sequence of Under the Olive Trees. There we are not told what the girl replies when the boy runs after her and proposes marriage one last time. In that case, too, I decided one way, David the other. Years ago we told Kiarostami this, and he laughed and said men tend to assume the girl accepts him, while women assume she rejected him. (I think there actually are some fairly clear clues earlier in the film that she will reject him, but explaining those would be a different entry.) That may be the case here, that men and women will reach opposite conclusions.

On the other hand, and this would require at least a second viewing, the film may remain utterly ambiguous about which plot is “real.” Or it may even stray into the territory of the inexplicable, à la Buñuel or David Lynch, where the difference parts of the story are each “true” but incompatible. M. Tsai suggests, “‘Certified Copy’ plays out a bit like a romantic comedy directed by David Lynch with its distinct two-halves connected by a thread.” (Not to be read until you’ve seen the film.)

Apart from its teasing, baffling, shifting elements, Certified Copy contains two fine lead performances and, of course, some beautiful cinematography. There’s a bit of a surprise, in that Kiarostami for the most part avoids his characteristic sweeping views of landscapes. Tuscan hilltop towns would seem to be perfect for his typical shots of vehicles struggling up bending roads, but we are largely confined inside the car during the driving scene, watching the characters and not the glimpses of trees through the windows. Those yearning to see Italy must be content with stone or painted stucco walls (as at the left).

Apart from its teasing, baffling, shifting elements, Certified Copy contains two fine lead performances and, of course, some beautiful cinematography. There’s a bit of a surprise, in that Kiarostami for the most part avoids his characteristic sweeping views of landscapes. Tuscan hilltop towns would seem to be perfect for his typical shots of vehicles struggling up bending roads, but we are largely confined inside the car during the driving scene, watching the characters and not the glimpses of trees through the windows. Those yearning to see Italy must be content with stone or painted stucco walls (as at the left).

For many links to articles and reviews, see David Hudson’s helpful wrap-up on Mubi. (Again, not until you’ve seen the film.)

Sodankylä Forever (Finland; dir. Peter von Bagh, 2010)

DB here:

Do writers write books about fanatical readers? Do composers write operas about opera lovers? Sometimes, but not to the degree that cinephiles delight in making films about their passion. Case in point: Peter von Bagh’s Sodankylä Forever. The Festival screened two films devoted to Finland’s Midnight Film Festival, which not only runs movies around the clock but hosts marathon interviews with filmmakers.

It isn’t your usual red-carpet event. The town is tiny. Guests are treated to campfire cookouts and invited to play soccer. But watching old clips, catching snatches of the Johnny Guitar theme, and hearing revered directors spin their yarns is enough to bring pleasure. There are moments of drama—Zanussi and Makavejev boycott a screening of Potemkin because of its “totalitarian” ideology—but mostly the filmmakers muse in a relaxed fashion about the good, and bad, old days.

The Yearning for the First Cinema Experience treats a core cinephile topic: What was your earliest encounter with the movies? Disney films, as you might expect, play a major role, but so too does Frankenstein (which made Victor Erice realize that people kill other people) and even the MGM lion (which startled Kiarostami in his childhood). The First Experience includes more mature epiphanies, such as Bob Rafelson’s obsessive visits to Manhattan’s Thalia. If the official classics get particular attention, it’s perhaps because, as Costa-Gavras says, “Everything was done in the silent cinema.”

So cinephiles are nostalgists, sentimentalists, even narcissists. But we aren’t oblivious to history behind the screen. The Century of Cinema episode focuses on directors’ relation to World War II (a continuing fascination of von Bagh’s). An era of purges, battlefront savagery, and prison camps, created, Szabo reflects, “a generation without fathers.” Jancsó, who served time in a Finnish POW camp, pays tribute to his hosts with a recitation, in Hungarian, of the opening of the Kalevala.

After the war, however, several Western European directors recall the advent of a new era of intelligence and creative engagement. The spirit was most apparent in the Italian Neorealist films. Erice tells of sneaking a forbidden print of Rome, Open City out of customs so that Spanish cinephiles could see it. In Eastern Europe, of course, things were different, and tales of censorship and young directors’ struggle to innovate are treated as continuations of wartime crises and constraints. Alexei German sums up the status of the artist who refuses to affirm official culture: “We are not the doctors, we are the pain.” Samuel Fuller, who has already explained that being assigned to a rear-guard unit in a retreat is a death warrant, is given the epilogue. He recalls visiting the tidiest graveyard he has ever seen and turning to watch the wind rustling the grass. Was he imagining how the scene would look on film? Naturally, arch-cinephile von Bagh shows us.

DB, Abbas Kiarostami, KT. Chicago, March 1998.