Another dispatch from Vancouver

Saturday | October 9, 2010 open printable version

open printable version

Kristin here:

Surviving Life (Czech Republic; dir. Jan Švankmajer, 2010)

I became a fan of Švankmajer’s work back in 1988, when I saw Alice, his first feature. David and I gradually explored his shorts and discovered that some of them were among the great classics of the animation form, perhaps most notably Jabberwocky and Dimensions of Dialogue. Švankmajer mostly concentrated on object animation, often combining found objects like tools, stuffed animals, dentures, and food in bizarre ways to create figures.

But after Alice, Švankmajer continued to make features, and they contained less and less of what he was best at: animation. Faust was all right, but I suffered through Conspirators of Pleasure and skipped Lunacy altogether. The director has claimed that Surviving Life is to be his final film, so I thought I owed him a last chance. It’s lucky I did, since it’s a real comeback for him, and a return to what he does best.

Whether Švankmajer really wanted to eschew live-action filmmaking and take up animation again is a moot point. He appears in a prologue, not exactly as himself but as a pixillated cut-out photographic figure (apart from the same typical cut-ins to real speaking mouths that became rather tedious in Alice). He describes how he intended to make a live-action feature, but with a small budget could only afford cut-out animation. He demonstrates by hopping about the frame like a figure in a child’s TV show. At the end, he checks how much time the prologue has taken up–two and a half minutes–and mutters that it’s not very long. His mordantly amusing speech doesn’t suggest whether he really had tried to make the film with live action. Indeed, the actors who are represented by the cut-out photographs obviously had to act out their movements, in costume, and to provide their voices. How much cheaper all this could be is debatable.

The story is about dreams, and specifically about a man stuck in a dull desk job who dreams of an exotic woman in red. His doctor sends him to a psychiatrist whose office contains photos of Freud and Jung, each of whom listens and reacts with applause or contempt when his own or his rival’s theory is employed. The hero is horrified when he discovers that the psychiatrist is trying to rid him of his dreams when his own desire is to live within them.

We tend not to think of cut-out animation when we think of Švankmajer, but predictably he proves a master of it. At times the technique resembles that of Terry Gilliam in the animated interludes of Monty Python’s Flying Circus, especially in scenes shot in a black-and-white cityscape with surrealist objects emerging from the windows (see above and below). The “actors” appear as smoothly animated photographs except for close shots, when the actual actors are shown. The technique works brilliantly, with the cuts between the image and the real person being smoother than most Hollywood matches on action.

If Švankmajer has chosen this as his swan song, he has gone out reminding us why we admired him in the first place.

The White Meadows (Iran; dir. Mohammad Rasoulof, 2009)

There are probably a lot of indirect comments on the political situation in Iran in films from that country. Some are obvious to all, others no doubt only to people who live that situation every day. Few, however, can be so overtly allegorical as The White Meadows. Oddly, the allegorical implications are so clear that they can be grasped immediately and do not impinge on the intriguing strangeness of the tale being told.

The central figure is a man who rows his small boat across a highly saline sea, stopping at islands and coastal villages in deserts caked with salt formations. (Yes, another Iranian journey film.) At each stop he gathers the tears of the local people, gradually accumulating a small bottleful. Each stop also yields a fable-like incident that reflects the plight of certain sectors of Iran’s population: a beautiful virgin is sent as a sacrifice to a sea god, an unconventional artist who refuses to paint naturalistically is tormented and sent into exile, and so on. The overall impression is of universal suffering, and the ending suggests that this suffering benefits only the rich and privileged.

The white and tan landscapes and pale blue sky and sea provide stunning locales for this simple tale, shot around Lake Urmia in northeastern Iran.

While watching The White Meadows, one wonders how Rasoulof could get away with such an overt criticism of religious and governmental repression in Iran. He couldn’t, quite. He was arrested alongside Jafar Panahi (who edited The White Meadows) and about a dozen others on March 2. Fortunately he was released fairly soon, on March 17. What his future as a director in Iran is remains to be seen. The government has long tolerated having one set of films for local popular consumption and another that will be confined largely to the international festival circuit. Not surprising, since these days Iran’s filmmaking is one of the few areas in which the country is seen internationally in a positive light. Still, such a bitter yet appealing film clearly stretches such tolerance.

Every year it seems more and more likely that the increasingly tenuous new Iranian cinema will finally be snuffed out, and every year–so far–we see bold and imaginative films coming from that country. We can only hope that with the arrests earlier this year, we are not seeing the long-expected end.

The Strange Case of Angelica (Portugal/Spain/France/Brazil; dir. Manoel de Oliveira, 2010)

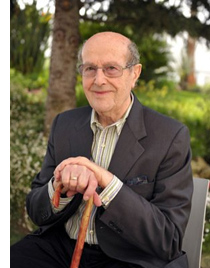

The fact that Oliveira was 101 when he made this film, as well as the fact that he is still directing at least a film a year (for last year’s Eccentricities of a Blond Hair Girl, see here), is too extraordinary not to be remarked on. Yet we shouldn’t let it dominate our view of Angelica or tempt us to treat it as an old man’s film. Slowly paced and meditative it may be, but it is also imaginative and full of humor, despite being centered around a young man’s obsessive love for a dead woman.

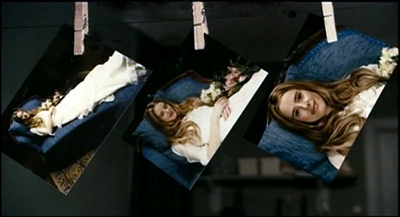

The protagonist, Isaac, is a photographer living in a boarding house in a town in the Duoro Valley region of Portugal. (Oliveira’s first film was a beautiful city symphony, Douro, Faina Fluvial, a poetic study of the river in the same valley made in 1931.) Called upon to photograph a beautiful woman who has died shortly after her wedding, through his viewfinder he sees the corpse open her eyes and smile at him. The same thing happens when he gazes at photos of her hung up to dry:

He falls in love with her, and her ghostly figure visits him at night, wafting him up into the air and flying over the river with him. Although he wakes from dreams several times, we are left in doubt as to whether Angelica really has been appearing to him.

The film seems to be set in contemporary times, and yet it has an old-fashioned look t it. The protagonist photographs men at work with hoes in a nearby vineyard, though his landlady remarks that no one does manual labor anymore. But most obviously, the film has the look and feel of a silent film. The shots of Angelica and the hero flying are superimposed ghostly figures straight out of Edwin S. Porter’s Dream of a Rarebit Fiend (1906). Camera movements are used sparingly, as in many silent films. Scenes often consist mostly of the hero taking his photographs or thinking of his phantom love, and his occasional cries of “Angelica!” could be rendered as intertitles. The use of solo piano music by Chopin reinforces the sense of watching a “silent” film.

(1906). Camera movements are used sparingly, as in many silent films. Scenes often consist mostly of the hero taking his photographs or thinking of his phantom love, and his occasional cries of “Angelica!” could be rendered as intertitles. The use of solo piano music by Chopin reinforces the sense of watching a “silent” film.

Yet there are occasional scenes of dialogue. The best scene in the film may be the one where over the breakfast table the other boarders discuss their concerns about Isaac’s state of mind. The scene ends amusingly with the camera holding on the landlady’s bird jumping around its cage, watched with great attention by her cat.

Oliveira will turn 102 on December 11. He is listed on Wikipedia has being in pre-production for A Missa do Galo.

Kawasaki Rose (Czech Republic; dir. Jan Hrebejk, 2009)

(Note: Many reviews and the VIFF program give the title as Kawasaki’s Rose, but the title on the film is as given above.)

This film creeps up on you. At first it seems poised to be yet another study of a failed relationship among upper-middle-class characters. A documentary is to be made about Pavel Josek, a noted professor famous for his past resistance to the Communists. The sound-man on the shoot is his son-in-law Ludek. His daughter Lucie has been told that a large tumor just removed is benign. Ludek confronts her with the fact that he has been cheating on her during her illness, and he undermines her efforts at disciplining their daughter.

But this conventional soap-opera material gradually opens out as files discovered during research for the documentary seem to reveal that Josek had in fact cooperated with the Communist regime, apparently including his participating in the torture of prisoners. From that point, Ludek recedes into the background and further political and personal revelations give the film considerable depth and complexity.

Kawasaki Rose was beautifully shot in full anamorphic widescreen, with images around the harbor in Göteborg, Sweden being particularly well composed.

While I was watching the film, I was reminded equally of Wajda’s Man of Marble and von Donnersmarck’s The Lives of Others. On the one hand, a film project that digs into the past of a heroic figure who turns out to be not quite so heroic, and on the other a study of the effects of interrogations into private lives under a totalitarian regime.

Kawasaki Rose (the title derives from an origami pattern and is given to a Japanese character in the film who paints flowers) is the Czech Republic’s entry for a foreign-film Oscar nomination. I wouldn’t be surprised if it gets one.