Archive for December 2010

Still cheating on video games

KT here:

Since I got back from England a month ago, I’ve been catching up with all the magazines that accumulated during the three weeks I was gone. Recently I read the November 15 issue of Newsweek. Initially I was happy to see the “Back Story,” the one-page article that comes at the end of each issue. It’s called “How Super Is Mario?” and compares the income of the video games and move industries. (It’s not available online complete unless you agree to a free trial of the online magazine. If you do, it’s here.)

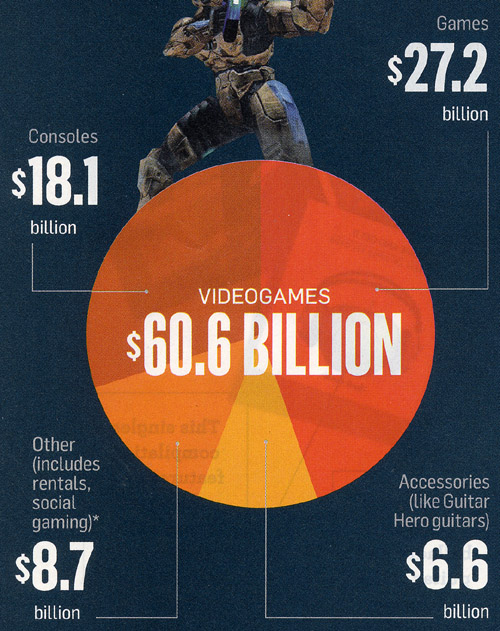

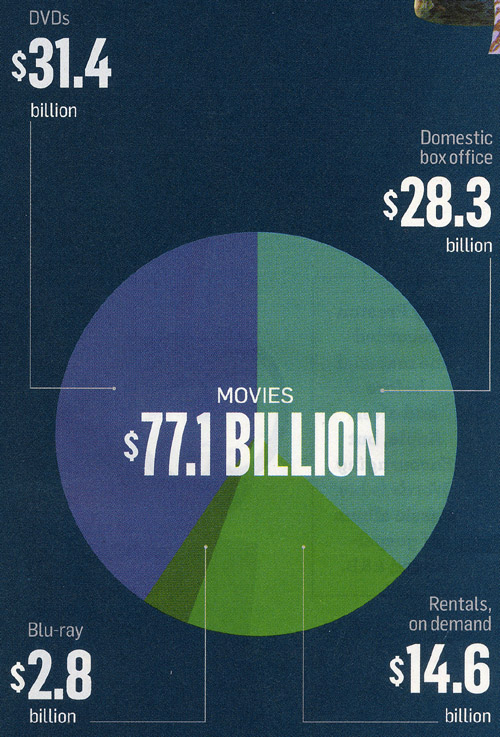

The article consists of two pie charts (above and below) and a brief text. At first the text sounded promising: “A big game—take September’s release of Halo Reach, for example—can sell millions of copies at about $50 a pop. That’s far pricier than any movie ticket, of course. But despite the conventional wisdom, the silver screen still rakes in more cash overall than the gaming industry, according to an analysis of recent revenue.” Great, I thought, at last a publication that makes an accurate comparison between the amounts of money brought in by games and by movies.

But in fact the Newsweek analysis just repeats the conventional wisdom it claims to overturn and makes the same old invalid comparison that entertainment-business journalism has been making since video games started making real money. A cursory glance at the pie charts makes it seem as if the gaming industry is not all that far behind films: the games total is $60.6 billion vs. $77.1 billion for movies. But let’s take a glance that isn’t cursory.

I’ll make the same point that I made in Chapter 8 of The Frodo Franchise (2007), where I deal with video games. There, too, I quoted a Newsweek article (from June 3, 2002): “In 2001, consumers snapped up $9.4 billion worth of game software and hardware—up 43 percent from the previous year—led by Sony’s world-beating PlayStation 2. Noting that the game industry had once again outstripped Hollywood’s box-office revenues, the head of Sony’s U.S. computer-entertainment division, Kaz Hirai, says his next target is the $18 billion home-video industry.” (225-26)

Note that reference to “software and hardware.” The figure includes the consoles and other equipment people buy in order to play games. But the pie chart of movie-industry income doesn’t include hardware. What would happen if the sales of theater and home projectors, DVD and Blu-ray Players, iTouches, and all the other gadgets used to watch movies were factored into the film-income figures? As we know, there have been a lot of digital theater projectors and 3D systems sold in recent years, not to mention all those portable media players. The games industry would fall farther behind than it already is. (And let’s not forget that most of those gaming consoles also play movies, so an indeterminate part of their income should go into the movies column. Since last January, the Wii even comes with a Netflix connection installed.)

As of 2004, the most recent year I could get figures for when I was writing my book, games software brought in $6.2 billion. That same year all forms of film distribution (including home-video and broadcast and cable television) grossed $45 billion.

Yes, games are gaining, but they’re not nearly as close to catching up with movies as media coverage would lead you to believe. The good thing about Newsweek’s recent pie chart is that it allows us easily to factor out the hardware income from the games’ side.

Consoles are listed at $18.1 billion and accessories at $6.6. Take them away, and games software brought in $35.9 billion in the period covered (January 1, 2008 to September 30, 2010). There’s nothing to take away from the film pie, since it consists entirely of software rentals and sales. So film still brings in more than twice as much, $35.9 billion vs. $77.1. DVD and Blu-ray sales, at $34.2 billion, make nearly as much as all games.

True, the games revenue has risen considerably in proportion to films since 2004. In that year, games made 13.8% of what films did. In the 21-month period covered by the Newsweek analysis, they made 46.6% as much. Will there be as big a jump proportionately in the next five years? Maybe. It’s possible that the move into streaming downloads as a distribution basis for home video will mean that movies simply cost less per view and hence will lose ground against games in terms of total income, if not in terms of popularity. Still, methods of distributing games might end up making them cheaper as well.

None of this takes into account that most mainstream blockbusters spawn a lot more ancillary products than do comparable video games.

I don’t know why entertainment journalists keep making this basic and pretty obvious mistake of continuing to include hardware sales only for games when they compare the success of these two media. It is after all their job to research the figures and analyze them in the way most useful to their readers. Giving those readers the erroneous impression that video-game sales have nearly caught up with film income doesn’t seem useful. The myth is probably something that the gaming industry fostered years ago to give the impression that it was more successful than more balanced comparisons would reveal. Journalists kept making the same kind of misleading comparison, which became the “conventional wisdom” that Newsweek only thinks it’s correcting.

As I point out in the same chapter of my book, game companies and film studios are not entirely in competition with each other. They cooperate to a considerable extent, since movies and games are often part of the same franchises. Some of the same people work on both. Often similar or identical technology is used in creating both. Increasingly film studios big and little have their own game-production units, and gaming companies are seeing more value in creating intellectual property that can be used across platforms. Some of the top film directors have been involved in creating games. Films routinely get adapted into games as part of their overall franchises, and some games get adapted as films. A successful film usually makes for a successful game, though the opposite isn’t yet as common. Though the industries do compete for leisure time and money, neither is out to kill the other. In many cases they’re out to boost each other’s success.

“I don’t hate anybody, not even my interrogators”

Jafar Panahi, May 2010.

DB here:

From Tehran comes the shocking news that Jafar Panahi, one of the finest of Iranian filmmakers, has been sentenced to six years in prison. The sentence also bans him from filmmaking for twenty years, forbids him to leave the country, and forbids him from giving interviews to the press, foreign or domestic. Panahi’s collaborator Muhammad Rasoulof was also sentenced to six years in jail.

This is the next step in a series of confrontations between Panahi and the government. He was earlier arrested for attending the funeral of Neda Agha-Soltan, the young woman shot in the 2009 protests. His passport was later seized. Before his most recent arrest he was forbidden to leave the country to attend the Berlin and Cannes festivals. Between March and May of this year he was in prison, during which he undertook a hunger strike. In May he was released on bail.

Since the mid-1990s Panahi has directed several extraordinary films, all explicitly or tacitly critical of aspects of Iranian society. Like his mentor Abbas Kiarostami, he attracted attention with films centering on children, notably The White Balloon (1995) and The Mirror (1997). The latter is a fine example of how Iranian directors have merged social realism, unexpected character psychology, and experimental storytelling strategies. The first half shows a stubborn little girl trying to get home from school. On a bus, she gets tired of pretending to be in a film and goes off on her own, with her microphone still attached. The crew tries to track her down, and much of the rest of the action takes place on the soundtrack, as we hear her encounters with street life and the crew’s commentary on what they manage to shoot. Sometimes the sound drops out entirely.

The Circle (2000) shifts to the adult world, illuminating critical moments in the lives of several women as they traverse the streets. Crimson Gold (2003), from a script by Kiarostami, shifts from presenting a crime-thriller situation to providing an unusual view of Tehran’s prosperous upper class. Offside (2006) won attention for its exuberant portraitsof women who disguise themselves as men to watch a soccer match. Panahi remarked drily to the court: “The space given to Jafar Panahi’s festival awards in Tehran’s Museum of Cinema is much larger than his cell in prison.”

The charges and the replies

The Mirror.

The oppression of filmmakers isn’t new, of course. Authoritarian political regimes across film history have banned films and punished their creators. In recent times, the Turkish actor-director Yilmaz Güney was imprisoned several times; while incarcerated, he wrote scripts to be filmed by others. After Devils on the Doorstep (2000), Jiang Wen was banned by Chinese authorities from film activities for some years, as was actress Tang Wei for appearing in Lust, Caution (2007).

But Güney was convicted of civil crimes, although of a political nature; his films were not, as I understand it, explicitly part of the charges. And although Jiang and Tang were punished for their film work, that punishment didn’t include jail time.

Panahi is in an unusually vulnerable situation. He is set to be imprisoned for preparing a film.

The official charges are “assembly and colluding with the intention to commit crimes against the country’s national security” and “propaganda against the Islamic Republic.” The authorities charge that he and his colleague Rasoulof were “preparing an anti-government film bearing on the post-electoral events” of June 2009, when thousands of Iranians protested the disputed reelection of President Ahmadinejad. “You are putting me on trial for making a film that at the time of our arrest was only thirty percent shot.” Panahi was shooting his film in his home, and government authorities seized the footage.

Other accusations sought to bolster the case. Panahi’s household, according to the prosecution, held “obscene films.” In his defense statement last month, he replied that these were film classics that have inspired him. He was charged with participating in demonstrations, but he replied that he was there to observe, and this was within his rights. He notes as well that he shot no footage of the demonstrations, acknowledging that filming was forbidden. As you know, on-the-spot reportage leaked out through Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube.

Panahi was accused of making his film without permission, but he responded that there is no legal requirement that a filmmaker obtain permission. He was accused of organizing protests at the opening of the Montreal Film Festival, but there he served simply as the head of the jury. He was charged with giving interviews to foreign media, but he pointed out that there are no laws forbidding someone from being interviewed. He was even accused of not giving scripts to his actors! He explained that he works with non-professional actors, and it’s common for Iranian filmmakers to simply explain what the actor must do and say.

The charges may be simply a pretext for silencing a prominent figure critical of current Iranian society. Panahi’s films do not circulate legally there, and he is widely believed to be in sympathy with liberal forces. The government has sought to eradicate the most visible of these factions, the Green Party. Even Islamic clerics have been swept up in the crackdown. A parallel case to Panahi’s is the attack on Mohammad Taqi Khalaji, a dissident cleric. Last January he was arrested and his computer and papers were seized. He too was incarcerated in Evin prison before being released on bail. Yet he was not formally charged with anything. His personal papers, including his passport, were not returned to him.

You can get some grim satisfaction for knowing that movies still matter in some parts of the world. Films have the power to shock bureaucrats and threaten authoritarian regimes. Instead of being simply “assets” or “content” to be extruded across platforms and shoved through release windows, cinema is in some places taken seriously as political critique.

Panahi’s case, his lawyer asserts, will be appealed.

Out of bounds

Offside.

Lest we Americans savor our superior virtue, consider this: Four months before 9/11, Panahi was traveling between Hong Kong and Argentina and stopped over in New York. He had been told he did not need a transit visa, but he was detained by American authorities at JFK Airport for lacking one. Here is Stephen Teo’s account in Senses of Cinema:

On his way to the Buenos Aires International Festival of Independent Cinema on 15 April, 2001, after having attended the Hong Kong International Film Festival, Panahi was arrested in JFK Airport, New York City, for not possessing a transit visa. Refusing to submit to a fingerprinting process (apparently required under U.S. law), the director was handcuffed and leg-chained after much protestations to US immigration officers over his bona fides, and finally led to a plane that took him back to Hong Kong. As far as is known, this incident was not reported in any major US newspaper, even though The Circle was being shown in the United States at the time (another irony: for that film, Panahi was awarded the “Freedom of Expression Award” by the US National Board of Review of Motion Pictures).

We are in the season in which critics are likely to use the word courage casually, as in “Natalie Portman gives a courageous performance in Black Swan.” The ongoing struggle of Panahi and thousands of his fellow Iranians remind us what real courage, in the world outside the movie theatre, looks like.

A petition addressed to Iran’s leaders in regard to Panahi and Rasoulof’’s case can be signed here. For one proposal for how world film culture could respond, go here.

A fairly detailed chronology of events around Panahi’s imprisonment can be found on Wikipedia. Panahi’s counter to the official charges, as well as the source of this entry’s title quotation, can be found here.

I have so far found no U.S. coverage of Panahi’s treatment in America in spring 2001. A report here from Australia suggests that he was detained but not arrested. Senses of Cinema has published Panahi’s letter to the Board of Review protesting his treatment on that occasion.

The case of Mohammad Taqi Khalaji is discussed here and here.

P.S. 22 December 2010: Yesterday Jonathan Rosenbaum posted his June 2001 review of The Circle. It’s an excellent piece, providing both in-depth analysis and broader context, and it does make reference to Panahi’s detention upon arriving in the U. S.

P.P.S. 22 December 2010: Thanks to Shelly Kraicer for a name correction.

P.P.P.S. 26 December 2010: Director Rafi Pitts has published an open letter to President Ahmadinejad about Panahi and Rasoulof’s sentence. Read it here at mubi.

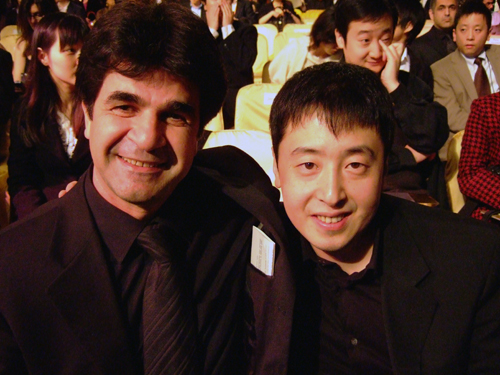

Jafar Panahi and Jia Zhang-ke, Asian Film Awards 2007. Photo by DB.

Three minutes of “Three Brothers”

Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows Part 1

Kristin here:

Last wee I went to see Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows Part 1. Behind the pack, of course, since it had been out nearly a month. But I dislike watching films in a crowd. My ideal is to be alone in the theater, which David and I managed last week with Megamind. In this case I picked the first matinee on a school day and saw the film at our local Sundance multiplex. (Yes, even Sundance runs some popular films to help support the less successful art films.) I figured that noisy youngsters, even if they skipped school to see DH1, wouldn’t go to Sundance. I was right. Four or five adults were sitting about ten rows behind me. I never heard a peep or crackling candy wrapper out of them. The film was really film, too, 35mm.

I had been curious about how the filmmakers would deal with some of the stranger aspects of J. K. Rowling’s seventh and final book. Breaking it into two parts seemed an obvious and smart move, and it does have less of a rushed feeling than the previous adaptations had. But Deathly Hallows the book has some very unconventional aspects.

For a start, Rowling reveals dark, indeed downright nasty things alleged about Albus Dumbledore, who up to this point has been your standard-issue comic-but-wise, twinkly-eyed mentor figure. I wondered if the film would dare to do the same. It does, but so far only as a very minor side issue. In the first part, at least, Harry is obviously distinctly miffed that Dumbledore hasn’t left him more information about how to deal with horcruxes, but he doesn’t seem to feel that his hero had feet of clay.

Second, it seems downright perverse on Rowling’s part that in a long series which has come to focus on the search for horcruxes and should just be working up its climax, she throws another set of mysterious, lost objects, the three Deathly Hallows, at us. Let’s see, six horcruxes, three hallows. What’s the difference? Which should the characters be seeking, and why? Is Voldemort after them, too? In the book, Harry becomes obsessed with finding the hallows, even though the horcruxes are the main point. That last premise, Harry’s obsession, hasn’t shown up in the film, so far anyway, but otherwise the hallows are fully treated in the film.

Finally, Rowling gives us a very long portion of the book where Harry, Hermione, and, for a time, Ron, are fugitives moving from place to place, camping out each night as they try to figure out where the remaining horcruxes are—and not having much luck either with that or with destroying the one they have obtained. I personally think this is a rather daring move. Given that for this long section we are confined entirely to Harry’s point of view, we get little sense of what is happening in the outer world. Naturally the film can’t spend quite as much of its length on this period of nomadic existence. Still, it does devote an unexpectedly long time to portraying it.

Some critics have complained that the action stalls during this portion. Others have noted that the slow-down allows for us at last to linger over the psychological states of the three main characters, who are being worn down by fear, frustration, and the horcrux’s presence. This stretch also displays some beautifully bleak locations, well filmed. Plus, as Rowling no doubt intended, this part of the narrative conveys a real sense of the characters’ seemingly hopeless position: They are in great danger and without any apparent clue as to where to look next.

One minor obstacle that I remember noting when I first read the book is that the hallows are introduced by having Hermione read aloud a fairy tale from the book Dumbledore has bequeathed to her, The Tales of Beedle the Bard. The tale, “The Tale of the Three Brothers,” occupies only about two pages, but having someone read that much text aloud in a film can be deadly.

The filmmakers came up with a solution that is both inspired and extremely well executed. As Hermione reads, we see a roughly three-minute animated sequence that illustrates her words.  The filmmakers have acknowledged that their model was Lotte Reiniger’s technique of silhouette animation, which she developed in the 1920s and used for such classics as The Adventures of Prince Achmed (1926). For DH1, similar silhouette effects are achieved with 3D digital animation.

The filmmakers have acknowledged that their model was Lotte Reiniger’s technique of silhouette animation, which she developed in the 1920s and used for such classics as The Adventures of Prince Achmed (1926). For DH1, similar silhouette effects are achieved with 3D digital animation.

I wondered who had designed and animated this little sequence and determined to watch for references to it in the credits. As is typical with effects-heavy films these days, several companies were listed and the credits rolled by too quickly for me to catch much. Still, I don’t think that the little film-within-a-film was mentioned specifically or its creator named as having been attached to it. Even Variety‘s review, which refers in passing to the sequence, doesn’t mention its maker.

A lot of other viewers were impressed enough to try and find out who was responsible. DH1 was released in the US on November 19, and by the next day, Cartoon Brew posted a story on the subject: “A number of readers have written to ask who animated the shadow puppet-inspired ‘Tale of the Three Brothers’ sequence in the new Harry Potter film Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows. It was directed and designed by Ben Hibon who produced it in association with Framestore.” Surprisingly, it also turns out that the section of Framestore that normally makes commercials did the “Three Brothers” scene.

I spent some time tracking Hibon down, finding some good-quality frames to display here, and locating clips. There are a few interviews with Hibon, plenty of clips and entire shorts, and filmographies. The video quality of some of these clips is dreadful, though, and a lot of the stories one finds via Google are short, repetitive pieces.

Most of this material is not all that easy to find, so herewith a guide to where you can most usefully find information on someone who seems to be an up-and-coming talent.

Hibon has designed video games, made music videos and commercials, done a short “screen” for MTV, and directed a few shorts and a trailer for a feature, A.D., which seems still to be in progress. The fullest filmography is the official one on the website for Hibon’s own company, Stateless Films.

Animation and effects expert Bill Desowitz has interviewed Hibon for Animation World Network. That’s recent, December 3, and deals exclusively with the DH1 scene. On November 23, fxguide posted an interview with Dale Newton, the sequence supervisor for the piece. An older, undated interview with Hibon on It’s Art Magazine concerns the series of five two-minute shorts collectively known as “Heavenly Sword.” These relate to a video game of the same name that Hibon designed. This series is visually quite distinctive, but it’s a far more conventional work than the “Three Brothers” short, being heavily influenced by anime.

Also on November 23, indiewire posted a short background article on Hibon, with several videos. With one exception, which I’ll get to shortly, don’t watch these films here or on YouTube. Why? Because the Stateless Films site has most of them and more. Hibon’s clips are larger and better quality than anything else I checked, plus they’re displayed with a black screen and far fewer distracting graphics than on YouTube. Click on the Archives link to see older works, including samples of Hibon’s work on videogames.

His site is the only place where I found a full version of his ad for the French bank, Crédit Agricole. The point of the ad is that this is the first green bank. It’s a gorgeous piece, full of images of pollution and decay gradually giving way to scenes of places restored to their pristine state and new, clean technology in place. Here are some images, from a vertical descent downward through a series of jet-trails (at bottom), a shot in which a wall of identical canned goods suddenly flies away to reveal a street market with fresh produce on sale, and windmills replacing old factory chimneys that fly apart:

There’s a dream-like quality to the whole thing, with a lot of shots, many with rapid movement, juxtaposed with slow, stately music.

The indiewire clips linked above include two shortened, English-language versions of this ad, with Sean Connery appearing to make the message explicit. There are also some Crédit Agricole ads made by more conventional filmmakers. Watch one or two of those, and you’ll find the contrast dramatic.

None of these sites and others with Hibon clips or shorts has the “Three Brothers” sequence, not surprisingly. That is, YouTube has some horrendous, out-of-focus subtitled auditorium videos, made in perhaps a South American or Spanish theater. Avoid like the plague.

Framestore’s site has some information on Hibon’s sequence, and the only clip from it that I could find. It’s very small and too dark to render the subtleties of the visuals, but there it is. Framestore also animated the two house-elves, Dobby and Kreatur, and there’s some information on that part of the project as well.

The January, 2011 issue of Cinefex has a story on DH1 that will undoubtedly include a section on the “Three Brothers” animation, but I haven’t seen that yet.

One reason that there are so many short pieces on Hibon on the internet is that at almost exactly the same time, on November 22, Variety announced that the filmmaker had been signed to direct a long-dormant New Line project, Pan. It’s a variation on the Peter Pan story, with the roles of villain and hero being switched; here Captain Hook is a detective on the trail of a certain child-kidnapper. The studio acquired the project in 1996, and for a while it looked as though Guillermo del Toro would direct. This time the film might get made, since the Variety story reports that it’s being cast and should start shooting next fall.