PLANET HONG KONG: Fanned and faved

Sunday | January 16, 2011 open printable version

open printable version

DB here:

Planet Hong Kong, in a second edition, is now available as a pdf file. It can be ordered on this page, which gives more information about the new version and reprints the 2000 Preface. I take this opportunity to thank Meg Hamel, who edited and designed the book and put it online.

As a sort of celebration, for a short while I’ll run daily entries about Hong Kong cinema. These go beyond the book in dealing with things I didn’t have time or inclination to raise in the text. The first one, listing around 25 HK classics, is here. The second, a quick overview of the decline of the industry, is here. The third, on principles of HK action cinema, is here. A fourth, a portfolio of photos of Hong Kong stars, is here. The next entry is concerned with directors, and the final one focuses on film festivals, with a list of a few more of my favorites. Thanks to Kristin for stepping aside and postponing her entry on 3D.

For a long time film academics lived in a realm apart from film fans. But over the last decade or so, the borders have been dissolving. Following the pioneering work of Henry Jenkins in Textual Poachers (1992), academics have started to study fans. More strikingly, they have joined their ranks.

Aca-what?

Michael Campi, fan, and Chris Berry, aca-fan. Hong Kong International Film Festival, 2006.

My generation of 1970s film academics looked down what were then called film buffs, the FOOFs (Fans of Old Films), and the star-gazers who dwelled in Gollywood. We were going to make film studies serious. We over-succeeded. Actually, many of us were fans without admitting it. Many of my peers were shameless fans of Ford, Hitchcock, Fuller, et al. Is the appeal of the auteur theory a form of fannery?

Still, things seem qualitatively different now. I think that the Internet, the arrival of new generations brought up on tentpole movies and HBO, and a boredom with the Big Theory that cast its spell over official film studies, hastened the arrival of what Jenkins has called the Aca-Fan.

The Aca-Fan is a researcher immersed in fan culture without a trace of guilt or condescension. In 1973, a film professor’s office was likely to display a poster for Blow-Up and maybe another for Singin’ in the Rain (approved classic). Today the professor’s office is likely to have something more downmarket—a poster for The Matrix or Fight Club or a Beat Takeshi movie. Look on a bookshelf and you might also find a few Simpsons or Buffy action figures. The emergence of aca-fans lends support to the idea that today geek culture is simply the culture. As Xan Brooks put it in 2003, “We are all nerds now.” Or as Patton Oswalt remarks in his funny Wired essay, “All America is otaku.”

Zapped by zines

Stefan Hammond and Nat Olsen. Hong Kong City Hall, 1996.

Irresistibly drawn to Hong Kong films (the story is in the preface to PHK), I soon found myself in one pulsing zone of fan culture.

If you wanted to know something about this tradition in the late 1980s and early 1990s, your options were limited. There were the annual catalogues published by the Hong Kong International Film Festival, but they were hard to find overseas. Virtually no Western scholars had studied this popular cinema, and the occasional pieces in Sight and Sound, Film Comment, Positif, and Cahiers du cinema made you want more. That more was often delivered by the fans.

They were a mixed lot: followers of the splice-ridden 1970s martial-arts imports that played in hollowed-out downtown theatres; lovers of Godzilla, Ultraman, and Sonny Chiba who saw Hong Kong as another wild and crazy cinema; big-city cinephiles who sought out recent imports at the local Chinatown house; fanboys and –girls in flyover country renting videotapes from Asian food shops and crafts stores. While Internet 1.0 cranked up, they found an easier outlet: print. Designing pages with good old Xerox and cut-and-paste, they created magazines.

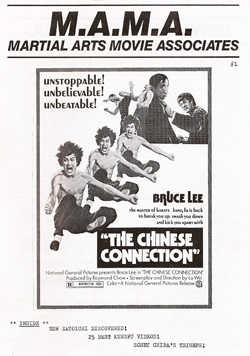

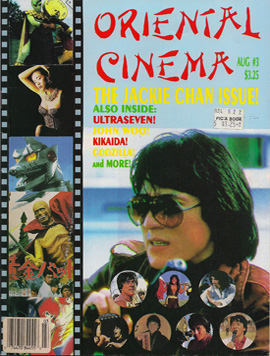

One distant progenitor was Greg Shoemaker’s Japanese Fantasy Film Journal (started in 1968), but the punkish Film Threat (1985) was also important, for it showed that deep-dyed fan publications with attitude could wriggle their way into magazine stands. Soon DIY Asian movie zines burst forth in gaudy profusion and gave the copy shops of the world a new clientele. The early production values recalled high-school poetry magazines, with ragged right margins and nearly illegible illustrations, but the content was compelling. An early entrant was the mimeographed M.A.M.A (Martial Arts Movie Associates, 1985), created by the authors of the still very useful From Bruce Lee to the Ninjas: Martial Arts Movies (1986). A step up in flair was Damon Foster’s Oriental Cinema. Lurid covers enclosed newsprint pages jammed with information, opinion, tawdry gossip, and pictures jaggedly assaulting text. Foster was probably the most colorful editor in the field, making his own films (notoriously, Age of Demons), offering his services as a mime for the blind, and boasting, “I’ve never gone to bed with an ugly woman, though I’ve woken up with quite a few.”

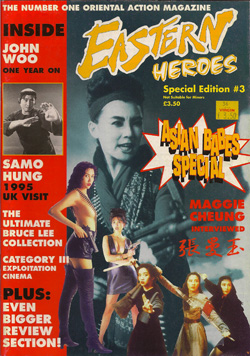

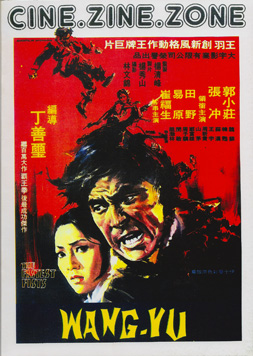

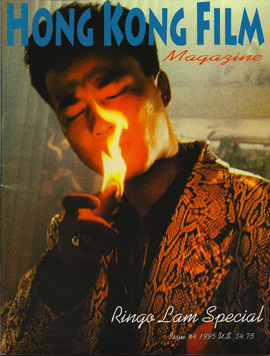

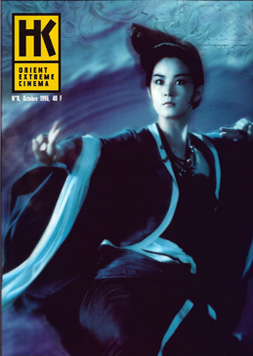

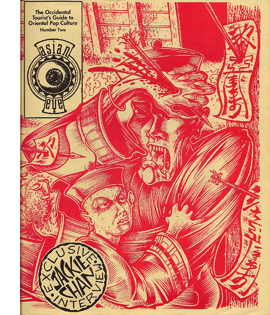

It was a far-flung community. Texas gave us Hong Kong Film Connection and Asian Trash Cinema (motto: “Good Trash Knows No Boundaries”). From Toronto came Colin Geddes’ Asian Eye (first issue: Guns Robots Ghosts Kung Fu). From Honolulu came Richard Akiyama’s Skam and then Cineraider, “published,” proclaimed the masthead, “a few times a year or less.” But soon real publishers brought out slicker magazines. San Francisco had Rolanda Chu’s Hong Kong Film Magazine. LA’s Giant Robot, a phantasmagoria of Asian lifestyles and pop culture, always ran some HK features, as did Tokyo Pop. The UK gave us Eastern Heroes (Free Van Damme Double Impact Poster Inside!) and Oriental Film Review. France had Cine.Zine.Zone, East Side Stories, and the Rolls Royce of the genre, the luxuriously printed HK: Orient Extreme Cinema. Some of these became fan magazines—professional magazines aimed at fans—as opposed to fanzines, magazines made by fans. The HK ones paralleled those devoted to anime, fantasy and science-fiction, and other realms of fandom. I couldn’t collect them all—I missed out on Fatal Visions, for instance—but in an era of scarce information, the ones I found were precious.

It was a far-flung community. Texas gave us Hong Kong Film Connection and Asian Trash Cinema (motto: “Good Trash Knows No Boundaries”). From Toronto came Colin Geddes’ Asian Eye (first issue: Guns Robots Ghosts Kung Fu). From Honolulu came Richard Akiyama’s Skam and then Cineraider, “published,” proclaimed the masthead, “a few times a year or less.” But soon real publishers brought out slicker magazines. San Francisco had Rolanda Chu’s Hong Kong Film Magazine. LA’s Giant Robot, a phantasmagoria of Asian lifestyles and pop culture, always ran some HK features, as did Tokyo Pop. The UK gave us Eastern Heroes (Free Van Damme Double Impact Poster Inside!) and Oriental Film Review. France had Cine.Zine.Zone, East Side Stories, and the Rolls Royce of the genre, the luxuriously printed HK: Orient Extreme Cinema. Some of these became fan magazines—professional magazines aimed at fans—as opposed to fanzines, magazines made by fans. The HK ones paralleled those devoted to anime, fantasy and science-fiction, and other realms of fandom. I couldn’t collect them all—I missed out on Fatal Visions, for instance—but in an era of scarce information, the ones I found were precious.

The fanzines were a rehearsal for the writerly gambits that would be played out high-speed on the web. Although wordage was costly in a print mag, an article could be as garrulous as a blog today. Concluding a report from a film set, the author notes: “If you found this report boring, then I am sorry. If you found it interesting, then I am glad.” The pages saw flame wars as well. “The retreading of that Amy Yip libel is but the tip of the proverbial iceberg for [your magazine] and other fanzines puking out unprovable sludge as though it were straight from CNN.” We watched all the games cinephiles play—exercising one-upsmanship, excoriating rivals, impressing newbies, and expressing pity or contempt for those wanting a snap course in hip taste. More often, there was the hospitality and a sincere urge to share l’amour fou that we find on fan URLs now. Within trembling VHS images, reduced to mere smears of color by redubbing, the writers glimpsed paradise.

I would read the zines for opinion-mongering, harsh or rhapsodic, and data delivery. Apart from pictures, usually of attractive women in swimsuits, the fanzines provided reviews (always with a ranking, usually numerical), interviews, and filmographies. There were lots of lists too; where is our Nick Hornby to commemorate the compulsive listmaking of this gang? Fandom is as canon-compulsive as any academic area, and as meticulous. One issue corrects an earlier Police Story review: “The synopsis indicated that Uncle Piao masqueraded as the aunt of Chan’s character. Actually, he disguised himself as Chan’s mother.”

Cultism reborn

Ryan Law, founder Hong Kong Movie Database and film programmer. Hong Kong, 2007.

As I discuss in PHK, upper-tier journalists usually learned of 1980s Hong Kong cinema from a parallel route, the festivals that began screening the films, usually as midnight specials. Visionaries like Marco Müller, Richard Peña, Barbara Scharres, and the New York group Asian CineVision boldly programmed Hong Kong movies. Critics, particularly David Chute in a 1988 issue of Film Comment, acted as an early warning system too. Meanwhile, the fans were amassing documentation. One zine might be given over to a film-by-film chronology of Jackie Chan’s career; another might solicit Roger Garcia to write about the tradition of Wong Fei-hong films.

One of fandom’s lasting monuments is John Charles’ vast reference book The Hong Kong Filmography 1977-1997, a detailed list of 1100 films with credits, plot synopses, and the inevitable ratings. Charles, a Canadian who wrote for many zines, has been a contributor to Video Watchdog, another generous source of Hong Kong data from the 1980s to the present. Many of Charles’ reviews are available on his site Hong Kong Digital.

By the mid-’90s the modern classics had become known to cinephiles throughout the west. A 1997 editorial announced that Hong Kong Film Connection, despite having a circulation of over 5000, could not continue. Why? Clyde Gentry III explained.

The fandom base has dropped considerably because they have been hand-fed ‘the list.’ You know. The list of films like A Better Tomorrow, A Chinese Ghost Story, Police Story and others that signify the popularity of these films as a collective. It’s even more of a shame that these people will walk away leaving an entire industry with a lot more than that to offer.

Once the canon was established, once everyone had reviewed the standard items and interviewed Michelle Yeoh, agitprop was no longer needed. Tarantino and Robert Rodriguez were spreading the gospel, and the surface dwellers could now get The List through real publishers like Simon & Schuster, which produced the still-enjoyable Sex & Zen and a Bullet in the Head. In the hands of Stefan Hammond, Mike Wilkins, Chuck Stephens, Howard Hampton, and other skilled writers, fan enthusiasm blended with turbocharged prose to bring the news to a broad audience in search of offbeat cinema.

Once the canon was established, once everyone had reviewed the standard items and interviewed Michelle Yeoh, agitprop was no longer needed. Tarantino and Robert Rodriguez were spreading the gospel, and the surface dwellers could now get The List through real publishers like Simon & Schuster, which produced the still-enjoyable Sex & Zen and a Bullet in the Head. In the hands of Stefan Hammond, Mike Wilkins, Chuck Stephens, Howard Hampton, and other skilled writers, fan enthusiasm blended with turbocharged prose to bring the news to a broad audience in search of offbeat cinema.

Soon, the Internet created a new era in fandom, with sites like alt-asian.movies newsgroup, Brian Naas’s View from the Brooklyn Bridge, and Ryan Law’s Hong Kong Movie Database. Some zines, like Cineraider and Asian Cult Cinema (Asian Trash Cinema redux), continued for a time online. HKMDB, another monument bequeathed to us by fan passion, remains a central clearing house of information, as do LoveHongKongFilm, Hong Kong Cinemagic, and others. The Mobius Home Video Forum became a robust conversation space devoted to Asian film, and other forums sprang up, most maintaining the old zest for discovery, unexpected information, controversy, and nostalgia. At Mobius the perennial topic, So what have you been watching lately?, has amassed 32,209 posts.

The zines and the Net made fans more influential. Some turned into critics and film journalists, and a few, like Shelly Kraicer, Colin Geddes, Ryan Law, and Tim Youngs, became festival mavens too. Frederic Ambroisine became an accomplished maker of documentaries on classic and contemporary Asian cinema. With Udine’s Far East Film and New York’s Subway Cinema, enterprising fans launched their own superb festivals.

Academics respect knowledgeable people with vigorous opinions, so I found a lot to like in Hong Kong fandom. And since the phenomenon played an important part in bringing the movies to western attention, I devoted some pages in PHK to it. Wearing my historian’s hat, I wanted to trace how fans helped build up a climate of opinion that with surprising speed created a canon and gave stars and directors international fame.

There’s a personal side to it too. Otaku I was, otaku I remain. (Comics, detective stories, Jean Shepherd, Faulkner, certain TV shows, and chess as a teenager; movies came later.) As a professor, I turned late to studying fans, but once I started, it felt like coming home. “Fan” is short for fanatic, and outsiders speak of cult movies. Both terms suggest deviant, even dangerous religiosity. The analogy isn’t far-fetched. Fans pursue revelation, as often as the remote control will yield it up. This search gives their subculture its own strange sanctity. In their frenzies and ecstasies we can glimpse a quest for purity.

For a useful lineup of HK fan sites, go here. Nat Olsen maintains a gorgeous site on Hong Kong popular culture and street life from his base in the territory. Grady Hendrix is everywhere at once, but he’s often to be found at Subway Cinema, an enterprise he and Nat founded with their colleagues.

I’m inclined to think that most people who study popular culture have great fondness for the things they study. Many film academics are cinephiles (that is, lovers of the medium itself). Others confess to great admiration for films or directors they study. So there was a fan potential latent in many researchers. But some academics evidently hate the films they write about. One friend of mine, a meticulous scholar of film and culture, doesn’t seem to enjoy any movies at all. This attitude seems to be most common when the writer takes on the task of denouncing some ideological shortcomings in the movie–its covert political messages, or its portrayal of ethnic or sexual identity. How can you love a film that is criminal?

This is a complicated matter; I note in PHK that many Hong Kong films present questionable attitudes toward police procedure, women’s roles, and other topics of social importance. The problem is that by today’s standards, virtually every artwork ever made can be interpreted to be “complicit” (a favorite word), in league with some objectionable world view. Recall the critic who heard a passage in Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony as “the throttling murderous rage of a rapist” (though she later modified her claim). By these standards, who shall ‘scape whipping? In a perfectly just society, will we have to stop watching Minnelli movies?

Granted, there are ways for the denunciatory critic to save a film that is she or he admires. It can be found to be secretly subversive, open to a “counter-reading.” Or it can be a work that openly challenges social norms, as with Surrealist cinema, gay/Queer cinema, or the work of Straub/ Huillet. Since the 1970s we have had films, mostly avant-garde ones, that seem to anticipate every possible line of objection that an academic critic might raise. But in any case you have to acknowledge that mass-production cinema is likely to call on prejudices and stereotypes. You don’t have to go as far as Roland Barthes, who noted that a “fecund” text needs a “shadow” of the “dominant ideology.” Nonetheless, our tasks as students of film, I think, is to recognize these factors but not to let them halt our efforts to answer our questions about other aspects of the films. As for love: Well, up to a point you can love a person despite his or her failings. Why not a film?

Lisa Odham Stokes and Tony Williams are other early HK aca-fans. Both have written for fanzines and have produced insightful books on Hong Kong films. See Stokes’ City on Fire: Hong Kong Cinema, with Michael Hoover, and Historical Dictionary of Hong Kong Cinema. A specialist in horror and action pictures, Tony has most recently published a study of Woo’s Bullet in the Head.

On fan culture, Henry Jenkins’ most comprehensive followup to Textual Poachers is Convergence Culture: Where Old and New Media Collide. An important recent collection is Jonathan Gray’s Fandom: Identities and Communities in a Mediated World. Online fandom and its role in promoting a film are analyzed in Kristin’s book The Frodo Franchise (Chapter 6) and her blog here. Patton Oswalt’s newly published Zombie Spaceship Wasteland is in parts a memoir from within fandom.

Thanks to Shelly Kraicer, Yvonne Teh, Peter Rist, and Colin Geddes for help jogging my memory for this entry.

Fans all: Peter Rist, Shelly Kraicer, Erica Young, Colin Geddes, and Ann Gavaghan. Hong Kong Film Awards, 2000.