Archive for January 2011

PLANET HONG KONG: One more visit

Hong Kong, Central, April 2008.

DB here:

Planet Hong Kong, in a second edition, is now available as a pdf file. It can be ordered on this page, which gives more information about the new version and reprints the 2000 Preface. I take this opportunity to thank Meg Hamel, who edited and designed the book and put it online.

As a sort of celebration, for a short while I’ll run daily entries about Hong Kong cinema. These go beyond the book in dealing with things I didn’t have time or inclination to raise in the text. The first one, listing around 25 HK classics, is here. The second, a quick overview of the decline of the industry, is here. The third discusses principles of HK action cinema here. A fourth, a portfolio of photos of Hong Kong stars, is here. That was followed by a tribute to western Hong Kong fans and then by a photo gallery of directors. Today’s installment is the last. Thanks to Kristin for stepping aside and postponing her entry on 3D, which will appear later this week.

Since the 1980s, the film festival circuit has become the only distribution system to rival Hollywood’s global reach. A big-name festival publicizes a film, some high-end critics at the festival write reviews, then once the film opens in a region or country, critics at large review it. As smaller festivals pick up films from the bigger ones, until eventually films make their way to small cities around the world. This process is parallel to the one that the studios orchestrate, though they have more centralized control. Video distribution, the circulation of DVD screeners, and Internet reviewing complicate this picture, but I don’t think they change the essential role of the festival network.

Just as film scholars have started to pay attention to fandom (see this post), they’ve started to ask research questions about festivals. As very few films from overseas find their way to U. S. screens, scholars keen on current cinema have realized that they need to visit festivals. It’s like scholars of painting traveling to exhibitions and gallery shows, or opera aficionados attending premieres at Bayreuth and La Scala. And film scholars of certain genres or periods have realized that they can do on-the-fly research by visiting historically oriented festivals like Pordenone and Bologna.

These days I see more of my colleagues at various festivals. In particular there’s the peripatetic Bérénice Reynaud, an early example of the multitasker (critic, programmer, professor, fan). On the same circuit I meet Virginia Wright Wexman, Peter Rist, Mike Walsh, Jim Udden, Gary Bettinson, and many other profs. So I’m starting to think that festivals are giving academic film studies a fresh charge of energy. Reciprocally, the events at Pordenone and Bologna, which began as cinephile events, have invited academic researchers to help program them and write for their publications. In sum, festivals are now a vigorous workspace for not just screenings and critical write-ups but discussions about ideas that would normally haunt the groves (or is it grooves?) of academe.

Saturation booking

Athena Tsui and Li Cheuk-to. Hong Kong, 2000.

I had dropped in at screenings at the New York and London film festivals in the 1970s and 1980s, and I had steadily attended the summer Cinédécouvertes series in Brussels. But I had never “done” a festival intensively until I went to Hong Kong in the spring of 1995. There I saw films that still stay with me: Through the Olive Trees, Postman, In the Heat of the Sun, A Borrowed Life, Smoking/ No Smoking, Quiet Days of the Firemen, Taebek Mountains, 71 Fragments of a Chronology of Chance, Whispering Pages, and Clean, Shaven. (My one big miss was Sátántangó; I had to wait years to catch up with that.) Who says the 1990s were a meager decade? Can any festival today come up with a menu like this?

I had gone, as I explain in the Preface to Planet Hong Kong, mainly to check on local cinema. The “Hong Kong Panorama” surveying 1994 releases yielded a bumper crop, including some titles I’d seen only on laserdisc (Chungking Express, Ashes of Time) and others that were revelations. Above all, there was a retrospective—an entire festival in itself, really—dedicated to early Chinese and Hong Kong cinema. They swept over me in a heaving wave: Love and Duty (1932), The Eight Hundred Heroes (1938), Boundless Future (1941), and many others, along with postwar Hong Kong classics like Where Is My Darling? (1947), Song of a Songstress (1948), The Kid (1950), with Bruce Lee, and on and on. The series was capped by stunning restored Technicolor prints of The Orphan (1960), also with Bruce, and General Kwan Seduced by Due Sim under Moonlight (1956). Some of these had circulated on poor VHS copies, but most were, and still are, unknown in the West.

I had picked the perfect year to come to the festival. Looking back at the notes I scribbled in the dark, I realize that over three weeks I got a crash course in Chinese film history. In any given day I was given more to think about, and certainly more to feel about, than I got from almost any academic conference.

For those of us interested in non-Hollywood cinema, festival programmers and critics are central gatekeepers. They scout the ridge and scan the horizon, and around the campfire they teach us film lore. They’ve built up fingertip knowledge about movies, moviemakers, distribution patterns, sales agents, theatre circuits—in sum, the workings of world film culture. The best of these gatekeepers are intellectuals, ready to search out something stimulating in even the most marginal film. They have honed their senses to detect qualities that could provoke an audience or yield a lively Q & A or a piquant catalogue entry or a solid review. Out of pure selfishness, I wish I could download the neural storage files of Alissa Simon, Richard Peña, Tony Rayns, Cameron Bailey, and their peers. Alas, there is no app for that.

In Hong Kong I met Li Cheuk-to, Jacob Wong, Freddie Wong, and many other programmers, along with Athena Tsui and Shu Kei. What made my experience that spring of 1995 so thrilling were their months of patient planning and sleepless nights behind the scenes—finding the prints, arranging for them, writing catalogue copy and, not least, assembling a massive reference work like Early Images of Hong Kong & China, one of the precious books the festival managed to turn out every year to document the local cinema.

Many programmers are also critics, and such was the case in Hong Kong. When I arrived, Cheuk-to and his colleagues had just formed the Hong Kong Film Critics Society, and I was invited to their first awards ceremony. They were mostly young, and after the awards were handed out I was invited out to dinner with several of them. It was then I realized that here was a local film culture in which criticism mattered. Hong Kong was small enough for critics to band together to debate their cinema. Soon another critics’ group was founded, and the debates spread. I started to understand that if one were to study a film culture, one would have to grasp the dynamics of taste among schools of critics and between critics and their audiences. I made an effort to describe this dynamic in the second chapter of Planet Hong Kong.

It’s not just that that book had its origins in that first visit. And it’s not just that the newest edition is the result of my attending the festival for the last fifteen years. More important, my ideas about film and about the world changed when I met critics, programmers, and other academics in Hong Kong. Immersion in one of the world’s most fascinating cities had something to do with it too.

Favorites, for now

As Tears Go By (1988).

In my first entry in this hurriedly posted series, I listed around 25 Hong Kong films that most aficionados consider of major importance—historical, artistic, cultural, or all three. In the days since, I’ve mentioned several other films that you can check into. Here, as an envoi to this yakathon, are a few more movies that I’ve repeatedly enjoyed, and that I’ve sometimes talked about in PHK 2. They’re grouped in very loose categories.

Lesser-known items from major directors. Once a Thief is a good example. Sandwiched between Woo’s official classics is this good-natured, somewhat silly action comedy about art thieves, romance, and parenthood. Lifeline is one of my favorite Johnnie To Kei-fung films—not as formally audacious as his later masterpieces, but containing one of cinema’s great action sequences involving a fire that seems as unstoppable as a waterfall, with the bonus of a throat-catching epilogue. Ann Hui On-wah’s Summer Snow, about a busy career woman who must treat her Alzheimer’s-affected father, glows with the intimate realism and understated sentiment that inform her more recent The Way We Are.

Everybody knows some works by Wong Kar-wai, but I think his later accomplishments have overshadowed his debut, As Tears Go By, a prototype of the arty gangster movie. Drenched in romanticism, it has one of the great music montages in Hong Kong film and a finale that you feel lifting from genre formula to pictorial poetry. With Johnnie To as well, even offbeat items like Throw Down are getting well-known, but I’d like to make a pitch for the New Year’s mahjong comedy Fat Choi Spirit. It has some of the 1980s nuttiness; the laughs start at the DVD menu.

Tsui Hark has produced so many films that have been fan favorites–Peking Opera Blues, Once Upon a Time in China, and Swordsman III: The East Is Red–that you can’t expect anything worthy to be overlooked. And yet not enough people have seen the bouncy Shanghai Blues, with moments of musical rapture, and The Chinese Feast, with all his faults and virtues bundled into a celebration of cooking and eating. There’s also The Blade, a convulsive revenge saga that seems to me one of the best movies made anywhere in the 1990s. After it’s over, you’re not sure what hit you.

Drama, comedy, dramedy. Any reader of PHK knows my fondness for the gender-bending romance Peter Chan Ho-sun’s He’s a Woman, She’s a Man, a lovely integration of musical, coming-of-age story, and satire of sex roles. But my favorite Michael Hui film, Chicken and Duck Talk didn’t feature in the first edition because I couldn’t get my hands on a print to illustrate it. Tracing the rivalry between a scruffy duck restaurant and a Japanese knockoff of Colonel Sanders, it yields many hilarious sequences, perhaps most notably Hui’s efforts to conceal a plague of rats from health inspectors.

Chow Yun-fat made his western reputation in crime movies, but his local fans also love his comedies and dramas. Try the screwball Diary of a Big Man (right) in which Chow juggles two wives and enacts a music video; the wistful romantic drama An Autumn Tale; and of course the male melodrama All About Ah Long. Churning out six to nine movies a year, the man was a real movie star. In April 1995, I was waiting in line to see Peace Hotel and felt the crowd’s nervous anticipation. Three whole months had passed since they’d seen their friend in a new movie.

Chow Yun-fat made his western reputation in crime movies, but his local fans also love his comedies and dramas. Try the screwball Diary of a Big Man (right) in which Chow juggles two wives and enacts a music video; the wistful romantic drama An Autumn Tale; and of course the male melodrama All About Ah Long. Churning out six to nine movies a year, the man was a real movie star. In April 1995, I was waiting in line to see Peace Hotel and felt the crowd’s nervous anticipation. Three whole months had passed since they’d seen their friend in a new movie.

My associates sigh when I mention Wong Jing. What can I say? I find some of his films funny. Try Boys Are Easy, Tricky Master, and, probably my favorite, Whatever You Want. If you don’t like them, write my suggestion off as David in his Dotage. Speaking of silliness, I’m not over-fond of Stephen Chow, but All for the Winner, Flirting Scholar, From Beijing with Love, and A Chinese Odyssey are ingratiating enough. Square that I am, I like Shaolin Soccer too.

I’d add the medical melodrama C’est la Vie, Mon Cherie, the unpredictable cop stakeout movie Bullets over Summer, and the poignant Juliet in Love, about a triad’s attraction to a woman recovering from a mastectomy. Sylvia Chang Ai-chia’s quiet romantic dramas Tempting Heart and 20 30 40 are also rewarding. Patrick Tam Kar-ming’s films are still unjustly neglected, so anything might be considered obscure, but I was delighted when a passable DVD of My Heart Is that Eternal Rose was released. Here Tam lyricized the gangster movie; Wong Kar-wai took the next step.

For grotesque comedy, try You Shoot I Shoot, about a contract killer who adds value by having an aspiring director film the hits (complete with slo-mo) for the delectation of the client. Unclassifiable is The Inspector Wears Skirts II, a cop-training story that pits women recruits against dimwitted men. It includes a dance sequence displaying minimal skill and maximal cheerfulness.

Fight club: Of Chang Cheh’s vast output of martial-arts movies, I have a special affection for New One-Armed Swordsman, a spectacularly mounted action picture, and Crippled Avengers, in which “disabled” really does mean “differently abled.” For Lau Kar-leung, I especially admire Legendary Weapons of China, one of the strangest of his forays into the arcana of martial arts lore and Chinese history; Shaolin Challenges Ninja (aka Heroes of the East), a sort of Taming of the Shrew, but with throwing stars; and the harrowing Eight-Diagram Pole Fighter, something of a valedictory for the Shaolin tradition at Shaw Brothers. Both these directors made so many worthwhile films that you can spend a lot of agreeable time exploring their output.

Though not everyone agrees, I think that Corey Yuen Kwai is a fine director of action pictures, from the tonally discordant Ninja in the Dragon’s Den through the warrior-women saga Yes, Madam!, the vigilante-justice Righting Wrongs (incredible, literally, final airborne sequence), and Saviour of the Soul, a futuristic fantasy with one shot looking forward to Chungking Express (right). Yuen’s Fong Sai-yuk films and Bodyguard from Beijing contain classic sequences—fighting on the heads of a crowd, on top of a precarious pile of furniture, in a hypermodern kitchen. Co-signing the first Transporter film, he turned in something resembling the classic Hong Kong style.

Though not everyone agrees, I think that Corey Yuen Kwai is a fine director of action pictures, from the tonally discordant Ninja in the Dragon’s Den through the warrior-women saga Yes, Madam!, the vigilante-justice Righting Wrongs (incredible, literally, final airborne sequence), and Saviour of the Soul, a futuristic fantasy with one shot looking forward to Chungking Express (right). Yuen’s Fong Sai-yuk films and Bodyguard from Beijing contain classic sequences—fighting on the heads of a crowd, on top of a precarious pile of furniture, in a hypermodern kitchen. Co-signing the first Transporter film, he turned in something resembling the classic Hong Kong style.

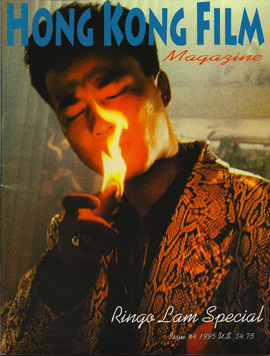

In the crime vein consider Kirk Wong’s hard-driving and pitiless Rock ‘n’ Roll Cop and Danny Lee’s Law with Two Phases (not a typo). Ringo Lam’s films are notably tougher and more tactile than those of his contemporaries; see his deromanticized classic City on Fire, the effort to out-Woo Woo that is Full Contact, and the lesser-known Full Alert. Eddie Fong Ling-Ching isn’t known for policiers, but Private Eye Blues was one of the films I enjoyed in the 1995 Panorama. His historical drama Kawashima Yoshiko is even more remarkable.

Connoisseurs know The Outlaw Brothers; one glimpse of the climax, in which a gunfight is interrupted by a hailstorm of poultry, usually convinces any viewer to take a closer look. I must add the below-the-radar ensembler Task Force, by John Woo protégé Patrick Leung Pak-kin. Gratifyingly untidy in skipping among the personal lives of a cop squad, it eventually focuses on the need to settle conflicts without violence—after, of course, supplying some snappy fight scenes of its own.

Post-handover take-outs. Most of the films I’ve mentioned are from the 1970s through the 1990s. But many worthy films have emerged in the 2000s. If they don’t always carry the effervescence of the earlier ones, many are solidly crafted. Some are discussed in Planet Hong Kong 2.0 and many more have received commentary on other websites (e.g., LoveHKFilm), so I’ll just mention a few that seem to me of more than transitory appeal.

Patrick Tam’s After This Our Exile is an unsentimental look at how an aggressive, heedless father must come to terms with his little boy. Needing You is a better-than-average office comedy, while Hooked on You is poignant in the gruff Hong Kong way, with a touching finale about the changes since 1997. Benny Chan Muk-sing’s action pictures usually deliver sturdy value in the old style. Try Connected, a remake of Cellular; New Police Story, with Jackie Chan as a cop coming to terms with age and failure in the face of nihilistic youth; and Invisible Target, which boasts an old-fashioned Hard Boiled demolition derby, with a police station ground zero this time. Horror fans already know how uneven HK films in that genre can be, but surely Fruit Chan Goh’s Dumplings is an admirably creepy achievement, and Soi Cheang Pou-soi did good work in the genre as well (Diamond Hill, Horror Hotline) before moving to the suspenseful Love Battlefield and the harsh action picture Dog Bite Dog.

Whew! After seven sword-like days, I’m running out of time, and I haven’t achieved a final victory. Want more dangerous encounters? Go to PHK or the Hong Kong Critics Society Award winnerss and start looking for your better tomorrow.

Sorry, I couldn’t resist.

Kristin and I discuss film festivals as an aspect of global film culture in Chapter 29 of Film History: An Introduction. For detailed research into the festival scene, see Richard Porton, ed., Dekalog 3: On Film Festivals and several publications from St. Andrews University. The most recent volume, edited by Dina Iordanova and Ruby Cheung, focuses on East Asian events.

P.S. Thanks to Yvonne Teh for a title correction, and Tim Youngs for a geographical one!

Photo: Joanna C. Lee, courtesy Ken Smith.

PLANET HONG KONG: Directors reframed

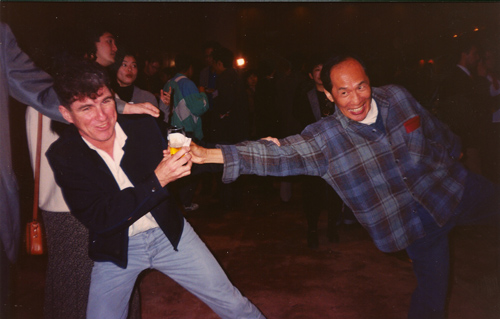

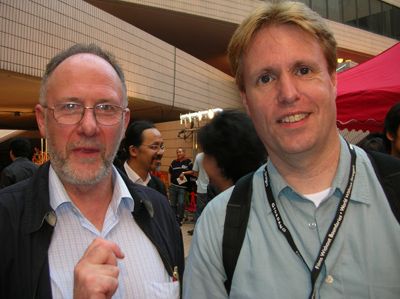

Your beer kung-fu is pretty good: Christopher Doyle and Po Chi Leung (Jumping Ash, He Lives by Night, etc.). Hong Kong Film Festival, 1996. Photo by DB.

DB here:

Planet Hong Kong, in a second edition, is now available as a pdf file. It can be ordered on this page, which gives more information about the new version and reprints the 2000 Preface. I take this opportunity to thank Meg Hamel, who edited and designed the book and put it online.

As a sort of celebration, for a short while I’ll run daily entries about Hong Kong cinema. These go beyond the book in dealing with things I didn’t have time or inclination to raise in the text. The first one, listing around 25 HK classics, is here. The second, a quick overview of the decline of the industry, is here. The third discusses principles of HK action cinema here. A fourth, a portfolio of photos of Hong Kong stars, is here. That was followed by a tribute to western Hong Kong fans. The final entry is concerned with the role of film festivals and a short list of other favorite films. Thanks to Kristin for stepping aside and postponing her entry on 3D.

When Andrew Sarris formulated an American version of the politique des auteurs, he used directorial “personality” as an index of true directorial creativity. Later, theorists and academics tried to define this elusive quality, and many concluded that auteur directors had recurring themes, a stylistic signature, and what we might call storytelling manner. To sketch an example: Welles can be thought of as concerned with the relation of power to love, and the loss of both. He favored aggressive depth compositions, long takes, and unusual uses of sound. In narrative terms, he was fond of stories featuring a larger-than-life man, turning on a puzzle or a crime, and presented in some time-shifting ways (e.g., flashbacks). This is a unsubtle characterization, but my point is simply that crtiics thought that recurring qualities like these offered a strong case for directorial authorship.

Yet a mass-market cinema makes “pure” authorship difficult, since directors may not freely choose their projects and their artistic preferences may be overridden by budgets, weather, producer rulings, censorship and the like. Creativity in a film industry, we’re usually told, requires collaboration. That’s true, but of course many other art forms do as well, notably theatre, dance, and song composition. A director may not explore favorite thematic concerns every time out (Look: stick to the script!), or may be thwarted in certain technical choices (We can’t afford long tracking shots!) or storytelling strategies (We’re adding a voice-over to clarify the backstory).

As with most high-output cinemas, the appeal of many Hong Kong films can be traced not to directorial flair but to the genre and other components (stars, scripts, studio resources). I wouldn’t say that many of the Jackie Chan-Sammo Hung-Yuen Biao outings like Winners and Sinners (1983), Wheels on Meals (this is not a typo; 1984), and My Lucky Stars (1985) exhibit much directorial personality, but they are skillfully made and pretty entertaining. Every industry needs its artisans, its steady hands on the tiller; it’s no mean feat to turn out a solid movie. Even the most distinctive directors in an industry need craft competence; as Sarris once remarked, “A great director has to be a good director.” Much of Planet Hong Kong is about the collective norms of local filmmaking, the tricks of the trade and the professional practices that shape the artistry of non-auteur movies.

But are there true Hong Kong auteurs? I think so, to various degrees. Ones discussed in PHK 2.0 are King Hu, Chang Cheh, Lau Kar-leung, Tsui Hark, Wong Kar-wai, and Johnnie To Kei-fung. John Woo, I argue, is one in a special, almost meta-sense: He understood the idea of authorship and crafted his public image, as well as his films, around certain themes (Christianity, heroic self-sacrifice) and stylistic choices (most visibly, flying pistoleros).

Wong Jing is a bit meta- too, in the way that Mel Brooks is a parodic auteur. Wong Jing’s farcical cinema carries to an extreme the vulgar potential always lurking in his territory’s cinema. He can provide quite precise mockery of other (better) directors, as when the arthouse filmmaker in Whatever You Want (1994) turns out a pretentious effort suspiciously similar to Ashes of Time. The evocative, fragmentary shots of Carina Lau Ka-ling clutching at her horse are replaced by one of Law Kar-ying caressing a cow.

So it was in hope of learning both about craft norms and directorial temperament that between 1995 and the present I’ve visited and talked with various filmmakers. The results are in the book, but here are some photos commemorating the encounters.

Here Ann Hui On-wah presents Wong Kar-wai with the best screenplay award (for Ashes of Time) at the first annual Hong Kong Film Critics Society Awards, 1995. She looks as happy as he is. The film also won Best Film, Best Director, and Best Actor (for Leslie Cheung Kwok-wing, who wasn’t present). For a further note on Wong, check the bottom of this entry.

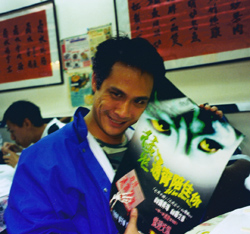

My longest stay in Hong Kong was during the spring of 1997. Doing research for PHK, I interviewed several people. One of my top stops was BoB & Partners, then the latest incarnation of Wong Jing’s entrepreneurship. (On the wall in the left still you see posters for Naked Killer, 1992, and other genre classics.) BoB stood for “Best of the Best,” and one of the partners was Andrew Lau Wai-keung, top-flight cinematographer who had become famous as a director with the Young and Dangerous series. Soon he was to go on to Storm Riders (1998) and eventually to the Infernal Affairs trilogy (2002-2003). Next door, Wong Jing also talked with me. He had several TV screens facing him, one with video games, and you can see his console front and center on his desk.

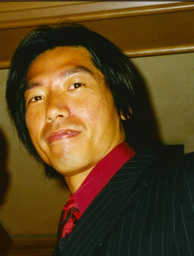

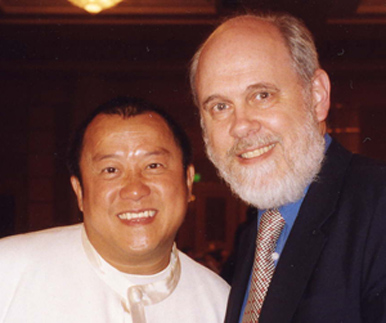

Another busy man, Peter Chan Ho-sun, had become an important director of contemporary comedies and dramas (e.g., He’s a Woman, She’s a Man, 1994; Comrades, Almost a Love Story, 1996). I met him in 1997 and brought him to Madison in 1999; below, a photo from 2008. Even more prolific, and less easy to categorize, is Herman Yau Lai-to–DP, rock-and-roller, and director of everything from grossout horror (The Ebola Syndrome, 1996) to harsh social critique (From the Queen to the Chief Executive, 2001; Whispers and Moans, 2007). How could you not learn a lot about filmmaking craft from a guy who had directed over fifty movies and been DP on thirty-five more? I wrote about Herman’s On the Edge here.

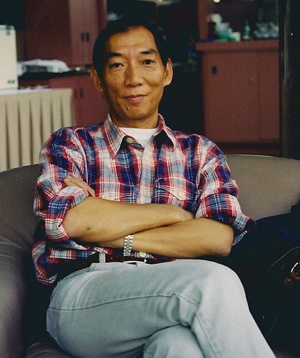

I met some directors from the older generation too. There was Yuen Woo-ping (aka Yuen Wo-ping), one of the great fight choreographers (The Matrix, Kill Bill) but also a lively director in exhilarating films like Legend of a Fighter (1982), Dance of the Drunk Mantis (1979), Iron Monkey (1993), and Tai-chi Master (1993). And there was Ng See-yuen, another local legend. He directed some sturdy kung-fu films like The Secret Rivals (1976) and The Invincible Armour (1977). He’s also an iconoclastic producer, backing Jackie Chan’s breakthrough film Snake in the Eagle’s Shadow (directed by Yuen Woo-ping), Tsui Hark’s Butterfly Murders (1979) and We’re Going to Eat You (1980), and several of the Once Upon a Time in China entries. Here Ng is at the 1997 Hong Kong Film Awards.

Two of the high points were my interviews with major figures of the Hong Kong New Wave of the 1980s, both still going strong in 1997. Ann Hui was warm and generous with her time; she visited Madison that year with Summer Snow (1995) and other films. The picture below is from 2005.

Then there was my several-hour talk with Tsui Hark at the Film Workshop headquarters. Good thing I taped it; I couldn’t keep up with him in my note-taking. He was planning Knock-Off and the animated version of Chinese Ghost Story.

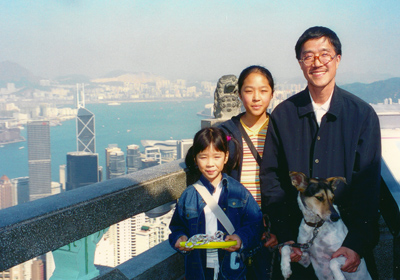

After 1997, I looked in on some other filmmakers. I was invited to visit the Academy for the Performing Arts in 2001 under the guidance of Professor Lau Shing-hon, another early New Waver (House of the Lute, 1980; The Final Night of the Royal Hong Kong Police, 2002). Here he is with his family on the Peak.

Since I started blogging, I have put my best (or rather the least amateurish) shots online. So for more snaps, you can rummage through the category, Festivals: Hong Kong. But I can’t resist two final ones. Here are Johnnie To and the younger director Soi Cheang Pou-soi (Love Battlefield, 2004; Dog Bite Dog, 2006; Accident, 2009), in shots from 2005 and 2009 respectively.

And now for something not quite completely different. In both print and e-book editions of Planet Hong Kong, I wrote about our last view of the Brigitte Lin Ching-hsia’s character in Chungking Express. Wong Kar-wai presents a jerky slow-motion shot of her leaving the crime scene and dodging out of the frame. It freezes on her, at a moment that yields a perversely unreadable image.

A shot of this frame would have been mud in the black-and-white pages of the book and probably not much better in the color pdf. I couldn’t imagine catching the faint reddish glint of the woman’s sunglasses. (Actually, the e-book’s quality turned out well enough that we might have tried for it.) So I picked the most legible image I could find from the shot, and that’s what’s in the print book and the digital copy (Fig. 9.13).

In any case, for obsessives like me, I reproduce the frozen frame here. This still comes from a 35mm print of the movie, and it is, of course, a lot more poetic than my snapshots, partly because it teases you about what’s in the frame.

PLANET HONG KONG: Fanned and faved

DB here:

Planet Hong Kong, in a second edition, is now available as a pdf file. It can be ordered on this page, which gives more information about the new version and reprints the 2000 Preface. I take this opportunity to thank Meg Hamel, who edited and designed the book and put it online.

As a sort of celebration, for a short while I’ll run daily entries about Hong Kong cinema. These go beyond the book in dealing with things I didn’t have time or inclination to raise in the text. The first one, listing around 25 HK classics, is here. The second, a quick overview of the decline of the industry, is here. The third, on principles of HK action cinema, is here. A fourth, a portfolio of photos of Hong Kong stars, is here. The next entry is concerned with directors, and the final one focuses on film festivals, with a list of a few more of my favorites. Thanks to Kristin for stepping aside and postponing her entry on 3D.

For a long time film academics lived in a realm apart from film fans. But over the last decade or so, the borders have been dissolving. Following the pioneering work of Henry Jenkins in Textual Poachers (1992), academics have started to study fans. More strikingly, they have joined their ranks.

Aca-what?

Michael Campi, fan, and Chris Berry, aca-fan. Hong Kong International Film Festival, 2006.

My generation of 1970s film academics looked down what were then called film buffs, the FOOFs (Fans of Old Films), and the star-gazers who dwelled in Gollywood. We were going to make film studies serious. We over-succeeded. Actually, many of us were fans without admitting it. Many of my peers were shameless fans of Ford, Hitchcock, Fuller, et al. Is the appeal of the auteur theory a form of fannery?

Still, things seem qualitatively different now. I think that the Internet, the arrival of new generations brought up on tentpole movies and HBO, and a boredom with the Big Theory that cast its spell over official film studies, hastened the arrival of what Jenkins has called the Aca-Fan.

The Aca-Fan is a researcher immersed in fan culture without a trace of guilt or condescension. In 1973, a film professor’s office was likely to display a poster for Blow-Up and maybe another for Singin’ in the Rain (approved classic). Today the professor’s office is likely to have something more downmarket—a poster for The Matrix or Fight Club or a Beat Takeshi movie. Look on a bookshelf and you might also find a few Simpsons or Buffy action figures. The emergence of aca-fans lends support to the idea that today geek culture is simply the culture. As Xan Brooks put it in 2003, “We are all nerds now.” Or as Patton Oswalt remarks in his funny Wired essay, “All America is otaku.”

Zapped by zines

Stefan Hammond and Nat Olsen. Hong Kong City Hall, 1996.

Irresistibly drawn to Hong Kong films (the story is in the preface to PHK), I soon found myself in one pulsing zone of fan culture.

If you wanted to know something about this tradition in the late 1980s and early 1990s, your options were limited. There were the annual catalogues published by the Hong Kong International Film Festival, but they were hard to find overseas. Virtually no Western scholars had studied this popular cinema, and the occasional pieces in Sight and Sound, Film Comment, Positif, and Cahiers du cinema made you want more. That more was often delivered by the fans.

They were a mixed lot: followers of the splice-ridden 1970s martial-arts imports that played in hollowed-out downtown theatres; lovers of Godzilla, Ultraman, and Sonny Chiba who saw Hong Kong as another wild and crazy cinema; big-city cinephiles who sought out recent imports at the local Chinatown house; fanboys and –girls in flyover country renting videotapes from Asian food shops and crafts stores. While Internet 1.0 cranked up, they found an easier outlet: print. Designing pages with good old Xerox and cut-and-paste, they created magazines.

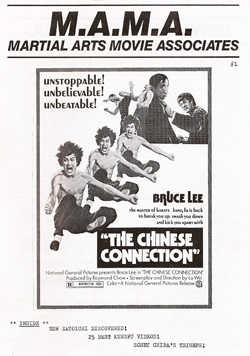

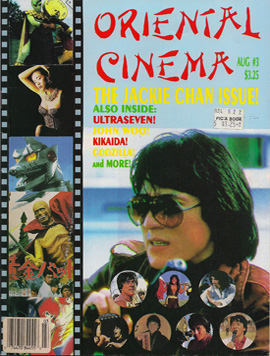

One distant progenitor was Greg Shoemaker’s Japanese Fantasy Film Journal (started in 1968), but the punkish Film Threat (1985) was also important, for it showed that deep-dyed fan publications with attitude could wriggle their way into magazine stands. Soon DIY Asian movie zines burst forth in gaudy profusion and gave the copy shops of the world a new clientele. The early production values recalled high-school poetry magazines, with ragged right margins and nearly illegible illustrations, but the content was compelling. An early entrant was the mimeographed M.A.M.A (Martial Arts Movie Associates, 1985), created by the authors of the still very useful From Bruce Lee to the Ninjas: Martial Arts Movies (1986). A step up in flair was Damon Foster’s Oriental Cinema. Lurid covers enclosed newsprint pages jammed with information, opinion, tawdry gossip, and pictures jaggedly assaulting text. Foster was probably the most colorful editor in the field, making his own films (notoriously, Age of Demons), offering his services as a mime for the blind, and boasting, “I’ve never gone to bed with an ugly woman, though I’ve woken up with quite a few.”

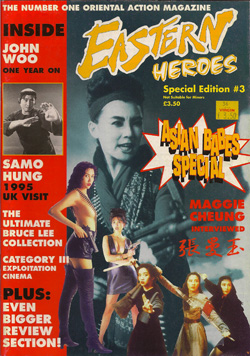

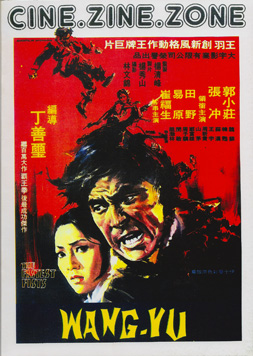

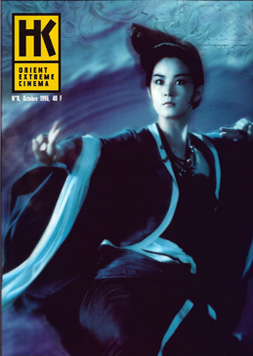

It was a far-flung community. Texas gave us Hong Kong Film Connection and Asian Trash Cinema (motto: “Good Trash Knows No Boundaries”). From Toronto came Colin Geddes’ Asian Eye (first issue: Guns Robots Ghosts Kung Fu). From Honolulu came Richard Akiyama’s Skam and then Cineraider, “published,” proclaimed the masthead, “a few times a year or less.” But soon real publishers brought out slicker magazines. San Francisco had Rolanda Chu’s Hong Kong Film Magazine. LA’s Giant Robot, a phantasmagoria of Asian lifestyles and pop culture, always ran some HK features, as did Tokyo Pop. The UK gave us Eastern Heroes (Free Van Damme Double Impact Poster Inside!) and Oriental Film Review. France had Cine.Zine.Zone, East Side Stories, and the Rolls Royce of the genre, the luxuriously printed HK: Orient Extreme Cinema. Some of these became fan magazines—professional magazines aimed at fans—as opposed to fanzines, magazines made by fans. The HK ones paralleled those devoted to anime, fantasy and science-fiction, and other realms of fandom. I couldn’t collect them all—I missed out on Fatal Visions, for instance—but in an era of scarce information, the ones I found were precious.

It was a far-flung community. Texas gave us Hong Kong Film Connection and Asian Trash Cinema (motto: “Good Trash Knows No Boundaries”). From Toronto came Colin Geddes’ Asian Eye (first issue: Guns Robots Ghosts Kung Fu). From Honolulu came Richard Akiyama’s Skam and then Cineraider, “published,” proclaimed the masthead, “a few times a year or less.” But soon real publishers brought out slicker magazines. San Francisco had Rolanda Chu’s Hong Kong Film Magazine. LA’s Giant Robot, a phantasmagoria of Asian lifestyles and pop culture, always ran some HK features, as did Tokyo Pop. The UK gave us Eastern Heroes (Free Van Damme Double Impact Poster Inside!) and Oriental Film Review. France had Cine.Zine.Zone, East Side Stories, and the Rolls Royce of the genre, the luxuriously printed HK: Orient Extreme Cinema. Some of these became fan magazines—professional magazines aimed at fans—as opposed to fanzines, magazines made by fans. The HK ones paralleled those devoted to anime, fantasy and science-fiction, and other realms of fandom. I couldn’t collect them all—I missed out on Fatal Visions, for instance—but in an era of scarce information, the ones I found were precious.

The fanzines were a rehearsal for the writerly gambits that would be played out high-speed on the web. Although wordage was costly in a print mag, an article could be as garrulous as a blog today. Concluding a report from a film set, the author notes: “If you found this report boring, then I am sorry. If you found it interesting, then I am glad.” The pages saw flame wars as well. “The retreading of that Amy Yip libel is but the tip of the proverbial iceberg for [your magazine] and other fanzines puking out unprovable sludge as though it were straight from CNN.” We watched all the games cinephiles play—exercising one-upsmanship, excoriating rivals, impressing newbies, and expressing pity or contempt for those wanting a snap course in hip taste. More often, there was the hospitality and a sincere urge to share l’amour fou that we find on fan URLs now. Within trembling VHS images, reduced to mere smears of color by redubbing, the writers glimpsed paradise.

I would read the zines for opinion-mongering, harsh or rhapsodic, and data delivery. Apart from pictures, usually of attractive women in swimsuits, the fanzines provided reviews (always with a ranking, usually numerical), interviews, and filmographies. There were lots of lists too; where is our Nick Hornby to commemorate the compulsive listmaking of this gang? Fandom is as canon-compulsive as any academic area, and as meticulous. One issue corrects an earlier Police Story review: “The synopsis indicated that Uncle Piao masqueraded as the aunt of Chan’s character. Actually, he disguised himself as Chan’s mother.”

Cultism reborn

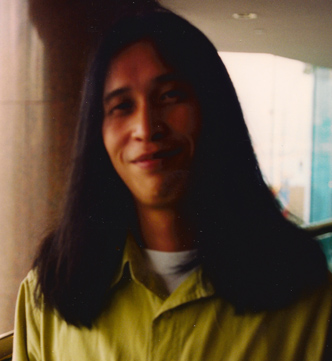

Ryan Law, founder Hong Kong Movie Database and film programmer. Hong Kong, 2007.

As I discuss in PHK, upper-tier journalists usually learned of 1980s Hong Kong cinema from a parallel route, the festivals that began screening the films, usually as midnight specials. Visionaries like Marco Müller, Richard Peña, Barbara Scharres, and the New York group Asian CineVision boldly programmed Hong Kong movies. Critics, particularly David Chute in a 1988 issue of Film Comment, acted as an early warning system too. Meanwhile, the fans were amassing documentation. One zine might be given over to a film-by-film chronology of Jackie Chan’s career; another might solicit Roger Garcia to write about the tradition of Wong Fei-hong films.

One of fandom’s lasting monuments is John Charles’ vast reference book The Hong Kong Filmography 1977-1997, a detailed list of 1100 films with credits, plot synopses, and the inevitable ratings. Charles, a Canadian who wrote for many zines, has been a contributor to Video Watchdog, another generous source of Hong Kong data from the 1980s to the present. Many of Charles’ reviews are available on his site Hong Kong Digital.

By the mid-’90s the modern classics had become known to cinephiles throughout the west. A 1997 editorial announced that Hong Kong Film Connection, despite having a circulation of over 5000, could not continue. Why? Clyde Gentry III explained.

The fandom base has dropped considerably because they have been hand-fed ‘the list.’ You know. The list of films like A Better Tomorrow, A Chinese Ghost Story, Police Story and others that signify the popularity of these films as a collective. It’s even more of a shame that these people will walk away leaving an entire industry with a lot more than that to offer.

Once the canon was established, once everyone had reviewed the standard items and interviewed Michelle Yeoh, agitprop was no longer needed. Tarantino and Robert Rodriguez were spreading the gospel, and the surface dwellers could now get The List through real publishers like Simon & Schuster, which produced the still-enjoyable Sex & Zen and a Bullet in the Head. In the hands of Stefan Hammond, Mike Wilkins, Chuck Stephens, Howard Hampton, and other skilled writers, fan enthusiasm blended with turbocharged prose to bring the news to a broad audience in search of offbeat cinema.

Once the canon was established, once everyone had reviewed the standard items and interviewed Michelle Yeoh, agitprop was no longer needed. Tarantino and Robert Rodriguez were spreading the gospel, and the surface dwellers could now get The List through real publishers like Simon & Schuster, which produced the still-enjoyable Sex & Zen and a Bullet in the Head. In the hands of Stefan Hammond, Mike Wilkins, Chuck Stephens, Howard Hampton, and other skilled writers, fan enthusiasm blended with turbocharged prose to bring the news to a broad audience in search of offbeat cinema.

Soon, the Internet created a new era in fandom, with sites like alt-asian.movies newsgroup, Brian Naas’s View from the Brooklyn Bridge, and Ryan Law’s Hong Kong Movie Database. Some zines, like Cineraider and Asian Cult Cinema (Asian Trash Cinema redux), continued for a time online. HKMDB, another monument bequeathed to us by fan passion, remains a central clearing house of information, as do LoveHongKongFilm, Hong Kong Cinemagic, and others. The Mobius Home Video Forum became a robust conversation space devoted to Asian film, and other forums sprang up, most maintaining the old zest for discovery, unexpected information, controversy, and nostalgia. At Mobius the perennial topic, So what have you been watching lately?, has amassed 32,209 posts.

The zines and the Net made fans more influential. Some turned into critics and film journalists, and a few, like Shelly Kraicer, Colin Geddes, Ryan Law, and Tim Youngs, became festival mavens too. Frederic Ambroisine became an accomplished maker of documentaries on classic and contemporary Asian cinema. With Udine’s Far East Film and New York’s Subway Cinema, enterprising fans launched their own superb festivals.

Academics respect knowledgeable people with vigorous opinions, so I found a lot to like in Hong Kong fandom. And since the phenomenon played an important part in bringing the movies to western attention, I devoted some pages in PHK to it. Wearing my historian’s hat, I wanted to trace how fans helped build up a climate of opinion that with surprising speed created a canon and gave stars and directors international fame.

There’s a personal side to it too. Otaku I was, otaku I remain. (Comics, detective stories, Jean Shepherd, Faulkner, certain TV shows, and chess as a teenager; movies came later.) As a professor, I turned late to studying fans, but once I started, it felt like coming home. “Fan” is short for fanatic, and outsiders speak of cult movies. Both terms suggest deviant, even dangerous religiosity. The analogy isn’t far-fetched. Fans pursue revelation, as often as the remote control will yield it up. This search gives their subculture its own strange sanctity. In their frenzies and ecstasies we can glimpse a quest for purity.

For a useful lineup of HK fan sites, go here. Nat Olsen maintains a gorgeous site on Hong Kong popular culture and street life from his base in the territory. Grady Hendrix is everywhere at once, but he’s often to be found at Subway Cinema, an enterprise he and Nat founded with their colleagues.

I’m inclined to think that most people who study popular culture have great fondness for the things they study. Many film academics are cinephiles (that is, lovers of the medium itself). Others confess to great admiration for films or directors they study. So there was a fan potential latent in many researchers. But some academics evidently hate the films they write about. One friend of mine, a meticulous scholar of film and culture, doesn’t seem to enjoy any movies at all. This attitude seems to be most common when the writer takes on the task of denouncing some ideological shortcomings in the movie–its covert political messages, or its portrayal of ethnic or sexual identity. How can you love a film that is criminal?

This is a complicated matter; I note in PHK that many Hong Kong films present questionable attitudes toward police procedure, women’s roles, and other topics of social importance. The problem is that by today’s standards, virtually every artwork ever made can be interpreted to be “complicit” (a favorite word), in league with some objectionable world view. Recall the critic who heard a passage in Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony as “the throttling murderous rage of a rapist” (though she later modified her claim). By these standards, who shall ‘scape whipping? In a perfectly just society, will we have to stop watching Minnelli movies?

Granted, there are ways for the denunciatory critic to save a film that is she or he admires. It can be found to be secretly subversive, open to a “counter-reading.” Or it can be a work that openly challenges social norms, as with Surrealist cinema, gay/Queer cinema, or the work of Straub/ Huillet. Since the 1970s we have had films, mostly avant-garde ones, that seem to anticipate every possible line of objection that an academic critic might raise. But in any case you have to acknowledge that mass-production cinema is likely to call on prejudices and stereotypes. You don’t have to go as far as Roland Barthes, who noted that a “fecund” text needs a “shadow” of the “dominant ideology.” Nonetheless, our tasks as students of film, I think, is to recognize these factors but not to let them halt our efforts to answer our questions about other aspects of the films. As for love: Well, up to a point you can love a person despite his or her failings. Why not a film?

Lisa Odham Stokes and Tony Williams are other early HK aca-fans. Both have written for fanzines and have produced insightful books on Hong Kong films. See Stokes’ City on Fire: Hong Kong Cinema, with Michael Hoover, and Historical Dictionary of Hong Kong Cinema. A specialist in horror and action pictures, Tony has most recently published a study of Woo’s Bullet in the Head.

On fan culture, Henry Jenkins’ most comprehensive followup to Textual Poachers is Convergence Culture: Where Old and New Media Collide. An important recent collection is Jonathan Gray’s Fandom: Identities and Communities in a Mediated World. Online fandom and its role in promoting a film are analyzed in Kristin’s book The Frodo Franchise (Chapter 6) and her blog here. Patton Oswalt’s newly published Zombie Spaceship Wasteland is in parts a memoir from within fandom.

Thanks to Shelly Kraicer, Yvonne Teh, Peter Rist, and Colin Geddes for help jogging my memory for this entry.

Fans all: Peter Rist, Shelly Kraicer, Erica Young, Colin Geddes, and Ann Gavaghan. Hong Kong Film Awards, 2000.

PLANET HONG KONG: Starstruck

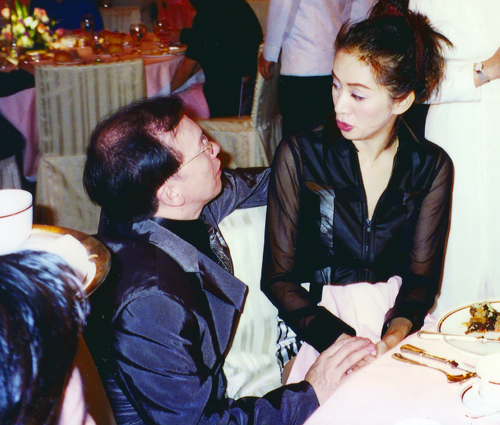

The late Anita Mui Yim-fong with Joe Junior. Hong Kong Film Awards party, April 1995.

DB here:

Planet Hong Kong, in a second edition, is now available as a pdf file. It can be ordered on this page, which gives more information about the new version and reprints the 2000 Preface. I take this opportunity to thank Meg Hamel, who edited and designed the book and put it online.

As a sort of celebration, for a short while I’ll run daily entries about Hong Kong cinema. These go beyond the book in dealing with things I didn’t have time or inclination to raise in the text. The first one, listing around 25 HK classics, is here. The second, a quick overview of the decline of the industry, is here. The third, on principles of HK action cinema, is here. The one following this considers western Hong Kong movie fans, the next entry focuses on directors, and the last entry reflects on film festivals, while adding a short list of some of my favorite HK movies. Thanks to Kristin for stepping aside and postponing her entry on 3D.

Today I want simply to share some photos I’ve taken of HK film performers over the last fifteen years. I’ll concentrate on the years B.B. (Before Blog)–that is, before 2007, when I began writing entries about my visits to the Hong Kong International Film Festival. Many other pictures of stars can be found in those annual entries, which can be accessed from this point on. I provide some links identifying the performers if you want to track down some films they were in. My snapshots’ quality isn’t professional–often my protagonists are bathed in tinted light–but for what it’s worth….

We reach back to the Analog Era, starting with my first visit to the Fragrant Harbour. Two couples at the 1995 Hong Kong Film Awards: Carina Lau Ka-ling and Tony Leung Chiu-wai; and Sandra Ng Kwun-yu and Simon Yam Tat-wah.

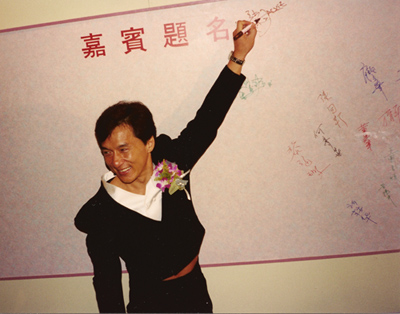

So on my first visit I was within viewing distance of two gods and two goddesses of Hong Kong film. Still, my most memorable moment came before the ceremony, when Jackie Chan came in and boldly wrote his name at the very top of the message board, above everybody else’s.

Two years later, when I was doing research for PHK, I met some performers in less public situations. This being Hong Kong, food was usually involved. Below, Francis Ng Chun-yu at a restaurant paused to promote his latest movie, Mad Stylist; and Shu Qi at Manfred Wong Man-chun’s fine restaurant.

Before you ask: Yes, I ate dinner with each of them. I was so dazzled I don’t remember a damn thing. Good thing I took pictures.

During the same 1997 visit, I managed to interview several filmmakers, one of whom was Anthony Wong Chau-sang. And what he said, I do remember. I took notes.

Alhough Anthony said it felt strange to be interviewed by a professor, he talked pretty freely. The interview ranged over acting styles (he was one of the few who experimented with the Method) and told some anecdotes about working with John Woo, Ringo Lam, and Kirk Wong. He also talked about his punkish rock music; who would think this gentle-looking guy was the lead performer on his classic “Let Thunder-God Gash All the Manic Bullies.”

One of the great things about Hong Kong is that stars from earlier eras are still treasured by younger moviegoers. I’ve seen Ti Lung, hero of many Shaw films of the 1970s and of the classic A Better Tomorrow (1986) several times, and he’s always surrounded by a swarm of young fans asking for his autograph. Here he is in a quieter moment at the 2001 Hong Kong Film Awards afterparty. Alongside is the ruggedly handsome Roy Cheung Yiu-yeung at the same event.

Earlier that evening at the Awards Michelle Yeoh was, as you’d expect, besieged by fans and news people.

Two from 2004: Jackie on the red carpet, more sedately dressed than before; and Eric Tsang Chi-wai.

Hong Kong Film Awards, 2006. An axiom of the 2000s Hong Kong cinema, Lam Suet; and Simon Yam again, this time with inveterate HK fan Mike Walsh.

Skipping ahead to 2008 and the premiere of Run Papa Run, here is the director, the ever-radiant Sylvia Chang Ai-chia, and one of her stars Louis Koo Tin-lok. I think of him as a newcomer, which he was when I was first visiting Hong Kong; but he has been in over sixty movies since 1994.

Also from 2008: Lau Ching-wan clowns in the kitchen of Paulina and Johnnie To Kei-fung, with Mrs. Lau (Amy Kwok) not at all put out. (More of Lau, from a few years earlier, here.)

One thing that struck me from my very first visit onward. Here stars are unbelievably approachable. Most enjoy meeting their fans, and they aren’t pretentious. This warmth adds to their lustre; glamorous as some stars are, they remain close to everyday people. As Leslie Cheung Kwok-wing put it, “In Hong Kong, once the audiences love you, they go on loving you for a very long time.”

The annual tribute to Leslie Cheung, held on the anniversary of his 2003 death; Mandarin Oriental Hotel, 2007.