Archive for January 2011

PLANET HONG KONG: The dragon dances

The Iceman Cometh (aka Time Warriors, 1989).

DB here:

Planet Hong Kong, in a second edition, is now available as a pdf file. It can be ordered on this page, which gives more information about the new version and reprints the 2000 Preface. I take this opportunity to thank Meg Hamel, who edited and designed the book and put it online.

As a sort of celebration, for a short while I’ll run a daily string of entries about Hong Kong cinema. These go beyond the book in dealing with things I didn’t have a chance to raise in the text. This is the third one. The first, a list of about 25 Hong Kong classics, is here. The second, an overview of the decline of the industry, is here. The fourth is a photo portfolio showing some stars; it’s here. Then comes an entry on western fandom, a photo gallery of director snapshots, and finally some reflections on the value of film festivals, capped by a list of some personal favorites. Thanks to Kristin for stepping aside and postponing her entry on 3D.

The longest chapter of Planet Hong Kong deals with action films. Here are some further thoughts on this fascinating genre.

Four aces of action

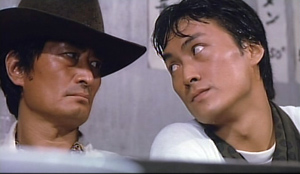

Tiger on Beat (1988).

Directing any action sequence poses several tasks. Once the stunts are decided upon, I can think of at least four such tasks.

1. The filmmakers need to present the physical actions clearly enough for the viewer to grasp them. Who hits whom, and how? What did X do to duck Y’s bullet? Which car is pursuing, which one is fleeing?

2. If the fight or chase is to be prolonged, one needs to come up with a series of phases that take the action into different areas of a locale, or into ever more dangerous situations. The classic arc is a fistfight that pushes the combatants to the edge of a cliff or roof, with the protagonist about to be shoved over. In other words, the action scene typically has a structure of buildup.

3. An action scene can express the emotions of the fighters—perhaps wrathful vengefulness on the part of one, versus cold calculation on the part of the other.

4. Finally, the filmmaker might want to try for a physical impact on the viewer. Just as sad scenes can make us cry and comic scenes can make us laugh, action scenes can get us pumped up. We can respond physically: we can tense up, blink, recoil, twist in our seat, and so on. How can the filmmaker achieve the level of engagement that Yuen Woo-ping emphasized in an interview with me: “to make the viewer feel the blow.”

I think that 1 and 2 are basic craft skills, with 3 and 4 being measures of higher ambitions on the part of filmmakers. Not everyone agrees. Philip Noyce says that incoherence (i.e., lack of clarity) is no problem:

I don’t necessarily think the audience member is looking for coherence; they are looking for a visceral experience. If they want coherence they can watch television.

Put aside the last comment, which begs for a bit more explanation. Noyce goes on to suggest a common rationale for lack of clarity: if the action’s confusing, it’s because the character is confused too. He praises Paul Greengrass’s framing and cutting in the Bourne films because

. . . The camera was used for its visceral possibilities rather than its literal ability. We felt the chase from the inside, where sometimes disorientation becomes an asset because it’s all about the velocity. Sometimes the pursuer and pursued don’t know where they are in relation to each other.

Greengrass’s fans have employed a similar argument, not so far from Stallone’s claims about The Expendables. It seems that many contemporary directors have concentrated on the fourth task, and to some extent the third, the expressive one (but only if the fighters’ emotion is disorientation). Job 1, basic and clear presentation, has become less important.

Yet it seems to me that the contemporary blur-o-vision technique doesn’t create a very sharp or nuanced impact. In effect, filmmakers try to amp up our response through jerky cutting, bumpy camerawork, and aggressive sound (which may be a major source of any arousal the movie yields). The result often doesn’t depend on what the actors do and instead reflects what can be fudged in shooting or postproduction. But we’re wired to react quite precisely to the movements made by living beings, human or not. If the film doesn’t make those movements at least minimally clear, we’re unlikely to sense anything more than a frantic muddle.

Further, Noyce doesn’t consider the possibility that a vigorous visceral effect can be created in and through coherent presentation of the action. The choice isn’t either/ or. The Asian action tradition, especially as practiced in Hong Kong, shows that we can have the whole package, often in quite elegant form.

OTT is OK

The Hong Kong tradition is probably most evident in its resourcefulness in fulfilling Task no. 2: creating an escalating pattern of mayhem and hairbreadth escapes. Filmmakers have been quite inventive in dreaming up outlandish twists in the action. The climax of Tiger on Beat (1988), from master Lau Kar-leung, indulges in what fans would call OTT (over-the-top) stuff. Above, outside a shop selling sailboats, Chow Yun-fat uses a clothesline to snap his shotgun out and blast the gang inside—becoming a literal gunslinger. Stepping up the intensity, Conan Lee Yuen-ba gets to work in a chainsaw duet.

The striking thing is that such flagrantly loopy combat is quite exciting, even exhilarating, while the realism that Noyce and Stallone promote can leave us fairly unmoved. Lesson: Artificially shaped grace can be tremendously arousing. Don’t forget how people get carried away watching dancing, acrobatics, or basketball.

I’ve speculated that the blur-o-vision action style is popular in Hollywood partly because it can suggest violence without showing it, so the sacred PG-13 rating isn’t at risk. No such qualms afflict Lau Kar-leung, who shows the main villain pinned to a table by Lee’s chainsaw. OTT again.

Note that each shot is from a different camera setup, typical of the Hong Kong “sequence-shooting” method. In addition, the whole scene integrates many elements of the setting into the fight. You get the impression that a Hong Kong action choreographer, stepping into a barber shop or a hotel lobby, instinctively thinks: What could be a weapon? What offers cover if someone rushes in with a gun? The Tiger shop yields barrels of paint, chainsaws, and worktables that can collapse under a man’s second-story fall. Even more exhaustive (and exhausting) is the classic fight at the end of Bodyguard from Beijing (1994). Here Corey Yuen Kwai, locking his antagonists in a modern kitchen, makes punitive use of not just knives and cutting boards but also the faucet and dish towels.

So part of what engages us in Hong Kong action is the filmmakers’ inventiveness in finding new ways to develop the basic premises of fights and chases. But this Tiger on Beat sequence also gives us the action in an utterly clear and cogent way. Every shot is brightly lit and crisply composed, with vivid colors in the sets, like those slashes of red. The cutting, while fast, makes everything totally intelligible through matches on action, obedience to the 180-degree rule, and a rock-steady camera. On top of all this, the thrusts and parries are given emotional force through the antagonists’ gestures and expressions (furious, startled, agonized). So conditions 1 through 3 are satisfied.

After this scene, we might ask Philip Noyce: Visceral enough for you?

Cutting to the chase

Matters of clarity, buildup, expressiveness, and impact on the viewer raise the perennial debate among Old China Hands, Martial Arts Division. To cut or not to cut?

For some aficionados, the less cutting the better. In classic kung-fu of the 1970s the full frame and longish take let actors show that they can do real kung-fu. No need to fake it through editing tricks. Actually, though, these films are quickly cut. Directors of the period realized that if the action is cogently composed, you can edit long shots as rapidly as you can close-ups.

No doubt, there are powerful effects you can achieve in the single shot. Admirers of full-frame action can point to an escalator gunfight in God of Gamblers, in which one passage is ingeniously staged in a single deep shot. Ko Chun’ s bodyguard Lung Ng fires at his pursuer in the upper floor.

His opponent falls down the opposite escalator, but another comes up behind, glimpsed in an aperture of the railing, and he fires at Lung.

Lung rises from the extreme foreground to return fire, and in the distance we see his attacker fall out of the slot at the railing.

On the big screen, you can feel your eye leaping from foreground to background, zigzagging across the frame. The dynamism of the action is mimicked in the rapid scanning we execute in taking it in. The eye gets some exercise.

Still, editing can serve my four purposes too. Some of the disjointedness of modern action scenes, we tend to say, comes from the speed of the cutting nowadays. Yet fast cutting can be quite coherent. There are about 490 shots in the twelve-minute climax of Tiger on Beat; nearly all are from different setups, and some are only a few frames long. Since the classic Hong Kong tradition builds upon a commitment to clear rendition of the action, it can use cutting to highlight information or repeat it. At one point, Chow whips his shotgun around a doorway and yanks his rope to pull the trigger on men he can’t see. We get five shots in three seconds.

The shots run, in order, 10 frames, 8 frames, 10 frames, 16 frames, and 38 frames. (I’m a frame-counter.) The lengthiest shot is about 1.5 seconds and the shortest is 1/3rd of a second. Yet each bit of action is so pointedly presented that it’s impossible to misunderstand, while the pace of the cutting forces us to keep up.

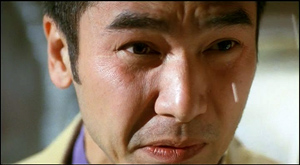

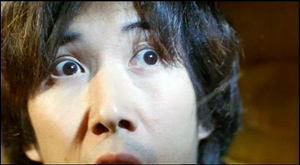

At an extreme, we have something like Sharp Guns (2001), a very low-budget, somewhat smarmy actioner that creates two spiky moments out of close-ups. Tricky On, the leader of our hit team, is pinned down alongside a mop-haired thug.

The kid recognizes him and raises his pistol in big close-up.

On, in even tighter close-up looks off, and the kid follows his glance.

A nearly abstract blade slices into the frame and the kid turns, his face going wan from the glare of the metal.

A hand thrusts. A neck bleeds.

Rack focus to On. Cut to Rain, the female assassin. The unfortunate thug’s head in the foreground of each shot specifies where each one is.

The fragmentation intensifies when soon afterward a blade whizzes leftward into the frame. In the next shot it glides past Tricky On.

On follows it with his eyes. Cut to another thuggish head, on his other side, with the blade embedded.

Rack focus again as the body slides down. Cut back to Rain, who has again saved her boss.

We haven’t had a single establishing shot in this sequence. The play of glances and turning heads, along with occasional foreground elements, lets us instantly understand that Rain has protected On from thugs on his left and right. Kuleshov would be happy.

Sharp Guns is surely no masterpiece, and you suspect that the close-up strategy pursued by director Billy Tang Hin-shing was a cheap way out. But give him credit for ingenuity, for well-timed cutting and movement, and for keeping the shots steady and legible. (Handheld shooting would dispel the force of the passage.)

Strongly marked cuts can also contribute a decorative punch. In A Better Tomorrow (1986), Chow is again pinned behind a door, and Woo cuts as he pokes his pistol around the edge.

The burst of that yellow slab in the new shot, counterbalancing the dark red of the earlier one, becomes the pictorial equivalent of a muzzle flash. Wouldn’t you like a bold cut like this in your film?

The pause that refreshes

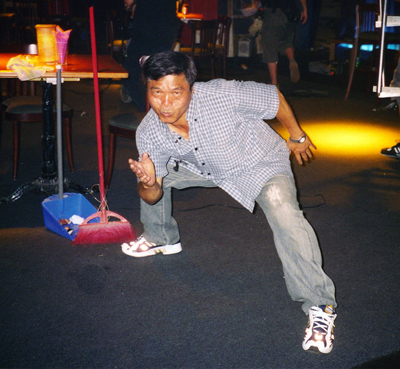

Choreographer Yuen Bun during the filming of Throw Down (2004).

These are pretty flagrant examples. More commonly, Hong Kong cuts serve to sustain a line of motion or break one off abruptly. Later in the Better Tomorrow gunfight, Chow swivels from one adversary to another, who comes sailing in from above. (Remember: Artifice isn’t bad. And John Woo was an assistant director to Chang Cheh, one of the gurus of the 1970s martial arts cinema. In those movies people fly all the time.)

Woo is famous for using slow motion, but here what prolongs the movement are the cuts. They continue the movement of the thug as he’s hit and starts to fall, but oddly they suspend him in time a bit too.

When he finally descends, the camera pans down with him as he lands on the car. The next shot completes the movement, putting us in the car as his head smashes through the window.

Like the Tiger on Beat sequence, this passage exemplifies what Planet Hong Kong calls the pause/ burst/ pause pattern characteristic of Hong Kong action scenes. In the shots above, the soaring thug enters the first shot 7 frames before the cut. The next two shots run 13 frames and 18 frames. Most interesting is the last shot, the one from inside the car. It lasts 62 frames, making it the longest in the series. 30 of those frames show the thug’s head crashing through the window, but the remaining 32 frames have no movement except for his swaying tie. The sequence has paused for a little more than a second, sealing off this bit of action.

Another editor might have interrupted this last shot while the head was in motion, but the Hong Kong pause/ burst/ pause principle creates a distinct rhythm. A moment of stasis is followed by a stretch of sustained movement, smooth or staccato, building to a peak; then another instant of stasis. This pattern contrasts with the unorganized bustle typical of American films’ sequences.

I think that the Hong Kong tradition has shown what benefits arrive when directors strive to fulfill the first three of my four action tasks. I don’t have time here to go further, but PHK argues that the first three goals form a basis for the fourth—a strong, deeply physical engagement with the action. This need not conform to standards of realism if it galvanizes our eye and accelerates our pulse. What Eisenstein dreamed of, filmmakers in Japan and Hong Kong achieved: a fusillade of cinematic stimuli that pull us into the sheer kinetics of expressive human movement. Through precise staging and cutting and camerawork and sound, these directors offered us not an equivalent for a character’s confusion (we live in that state much of the time) but a galvanic sense of what pure physical mastery feels like.

After writing this blog, I was reading Alex Ross’s fine essay collection Listen to This and came across his essay on Verdi, which in an aside (pp. 198-199) notes the pleasures of OTT unrealism.

Most entertainment appears silly when it is viewed from a distance. Nothing in Verdi is any more implausible than the events of the average Shakespeare play, or, for that matter, of the average Hollywood action picture. The difference is that the conventions of the latter are widely accepted these days, so that if, say, Matt Damon rides a unicycle the wrong way down the Autobahn and kills a squad of Uzbek thugs with a package of Twizzlers, the audience cheers rather than guffaws. The loopier things get, the better. Opera is no different.

For more on the construction of Hong Kong action scenes, see here and here elsewhere on this site. A fuller discussion is in Chapter 8 of Planet Hong Kong.

14 Amazons (1972).

PLANET HONG KONG: The little industry that could. . . . then couldn’t

DB here:

Planet Hong Kong, in a second edition, is now available as a pdf file. It can be ordered on this page, which gives more information about the new version and reprints the 2000 Preface. I take this opportunity to thank Meg Hamel, who edited and designed the book and put it online.

As a sort of celebration, for a short while I’ll run a daily string of entries about Hong Kong cinema. These go beyond the book in dealing with things I didn’t have a chance to raise in the text. This is the second one. The first, a list of about 25 Hong Kong classics, is here. The third, on principles of HK action cinema, is here. The fourth, a photo portfolio of HK stars, is here. The next installments focus on western HK fandom, on director snapshots, and on film festivals, the last including a list of some personal favorites. Thanks to Kristin for stepping aside and postponing her entry on 3D.

Seldom do historians get to write finis to the tales they tell. Who can tell when a process is played out? Yet sometimes you can’t avoid the sense that things have definitively ended.

That’s the case with Hong Kong cinema. Good, even great, films will still be made there, but that’s true of any territory. What made Hong Kong turn out so much lively cinema for so long was its large, robust film industry. Not exactly the Hollywood of the East, as Planet Hong Kong tries to show; it was erratic and seat-of-the-pants, less a large-scale enterprise than a cottage industry. Yet its scale did help it achieve a unique place in film history. Today there can be little doubt that the glory days of that cottage industry are gone. They started to go, in fact, about fifteen years ago.

Not 1997, 1994

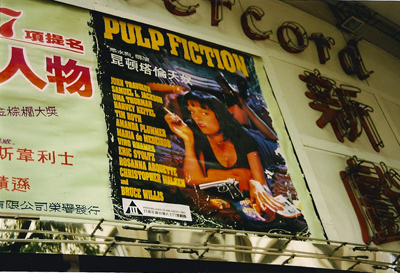

Silvercord Cinema, March 1995.

From the 1960s to the mid-1990s, the Hong Kong film industry ruled the East Asian market. Confronted with a small population in the Crown Colony (still under British control), filmmakers turned toward the much larger regional audience. They succeeded, wildly. In an era when most Asian nations couldn’t afford to import American films, the Hong Kong product boasted higher production values than films from other countries in the region (except Japan, of course). The films catered to the Chinese diaspora, a prosperous segment of most neighboring countries. Moreover, the industry offered major stars: the Shaws and Cathay stables at first, then Bruce Lee, Jackie Chan, Jet Li, and innumerable crossover faces from TV and pop music.

But things changed. Wasn’t the year 1997 the breaking point? After all, that was when the colony was handed over to Mainland China. Actually, PHK argued back in 2000, the slump started in 1993-1994. Thanks to overproduction, the exodus of talent, the rise of video piracy, and many other factors, the industry was in trouble well before the handover. Its problems were exacerbated by the Asian financial crisis of 1997, the 2002-2003 SARS outbreak, Internet piracy, the increasing success of South Korean cinema (and popular culture generally), and a powerful shift of investment and talent to the Mainland.

The new edition of the book gives details, but the dimensions of decline can be summarized.

*In most years between 1977 and 2002, between 100 and 234 films were released annually. (There was a significant drop in the years 1996-1998, an immediate reflection of the waning market.) After 2002, the number dropped steadily to about fifty releases per year. In 2010, Patrick Frater reports, there were 54 Hong Kong releases out of a total of 286 theatrical releases.

*Local movie attendance waned accordingly. In 1990, fifty million tickets were sold. In 1995, only 28 million were. Throughout the 1990s, ticket sales wobbled between about 17 million and 22 million. Recently, the number has been about 20 million.

*What proportion of local box-office receipts are claimed by local films? Again, 1994 proves a watershed. Before that, local films won between two-thirds and three-quarters of the market. But from 1995 on, the percentage shrank drastically. By the mid-2000s, Hong Kong productions were claiming less than a quarter of receipts. In 2009, 20.7 % of receipts went to local films—about US$31 million. The rest went to foreign imports, chiefly Hollywood movies.

*Before 1996, each year’s top ten box-office winners included between eight and ten local productions. It’s sad to trace the steep decline; by 2005 through 2008, only two films a year made it into the winner’s circle. In 2009 there was only one local film in the top ten. Last year there were two, and number ten was Gulliver’s Travels; how sad is that? America wins again.

*But Hong Kong’s market was chiefly a regional one. So how did the films do overseas? After 1994, not so well. The multiplexing of the world (one of the most important developments in global cinema history) gave Hollywood a strong entrée to places it had previously ignored. As Asian consumers became wealthier, they were drawn to the well-appointed theatres showing American movies like Jurassic Park (1993) and Speed (1994). Hollywood responded with blockbusters aimed at young and middle-class viewers in all countries, and soon its overseas receipts surpassed those from the United States. American films shoved Hong Kong films off both domestic and regional screens.

*Finally, what about China? Some locals thought that after 1997, Hong Kong would become China’s Hollywood. After all, the Mainland industry was backward, and Hong Kong had the money, the facilities, the skill sets, and the talent—especially stars that were household names in China. Sooner or later the PRC would need Hong Kong. Things did not work out that way, as I’ll discuss below.

The 2000 edition of PHK pointed to some of these factors, but an extra decade yields a longer view, and that lets us fill in more interesting detail. The old historians’ adage holds good: You really do need a stretch of time to see things more clearly. Of course you don’t have to go as far as Zhou Enlai. Asked about the effects of the French revolution, he is said to have replied: “Too soon to tell.”

Not a long time

Fire of Conscience (2010).

Speaking of Zhou, one thing I couldn’t foresee when I was writing PHK in 1997-1999 was the emergence of China as a filmmaking power. The mainland cinema was in pretty bad shape when Kristin and I visited the PRC in 1988, and things got worse in the next decade. For example, the number of cinema screens fell from about 140,000 in 1991 to 65,000 in 2001.

Again, though, things were changing. The PRC steadily stabilized the decline of its industry. It semi-privatized production, distribution, and exhibition. It let in American films and encouraged international investment to build up an infrastructure. The bureaucracy blocked a free flow of Hong Kong films into their market until 2003, at which point local exhibition was on the road to maturity. The audience grew but remained comparatively small: 115 million in 2000, 263 million in 2009. But receipts skyrocketed.

China’s cities were growing fast, and newly-prosperous urbanites turned to the new multiplexes built with Japanese, Korean, and Hong Kong investment. In 2001, box-office revenues were reported as US$77 million–about the same as tiny Denmark the same year. By the end of 2010, according to this Variety article, total box office looked to be about $1.5 billion—ahead of the 2009 receipts from the United Kingdom. (The UK is the second-biggest box-office territory in the EU.) The same Variety article quotes the head of China Film Group saying that he expected the figure to exceed $3 billion, which would easily make China the most lucrative market outside the United States.

Clearly China’s growth came at Hong Kong’s expense. A quota kept nearly most Hong Kong films out of China for nearly a decade. Now producers could enter only on the Mainland’s terms, with coproductions and joint ventures the primary options. Producers were eager to partner with what was likely the fastest-growing film market in history. After 2003 more and more Hong Kong films would have some PRC involvement—financing, location shooting, postproduction, technical staff, and of course stars. The Chinese market was so vigorous that producers began assuming they could make their films principally for the Mainland, not for their home audience. Only the most modestly budgeted film, a teen romance or slapstick comedy, could retain some local tang.

Planet Hong Kong traces this process in more detail, outlining some of the chief creative choices facing Hong Kong filmmakers in the 2000s and since. The Mainland is involved in nearly all of them, not just financially but ideologically. A historical action movie like Bodyguards and Assassins (2009) wins favor by focusing on the heroic efforts of a cross-section of Chinese to defend Sun Yat-sen during his stopover in Hong Kong. The academic, patriotic costume picture perfected by Zhang Yimou has been taken up by Peter Chan Ho-sun (The Warlords, 2007) and John Woo (Red Cliff, 2008-2009).

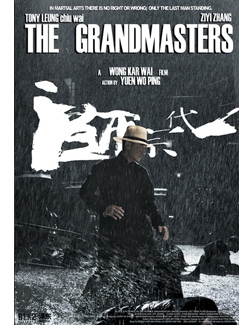

There is another, riskier option: Make films that can sell in the West. This has been Wong Kar-wai’s strategy as he has risen to the top of the festival and arthouse circuit. But after his venture into American indie cinema, My Blueberry Nights (2007), he too has shifted toward the Mainland, reviving the Ip Man project he announced several years ago, now known as The Grandmasters. (Ironically, so great is the power of American distribution that My Blueberry Nights was probably his best-performing film in theatrical release.) Johnnie To Kei-fung has pursued several avenues at once: while making films for Hong Kong, China, and the region he has also developed audiences in festivals and in limited theatrical/ video releases in Europe and the U. S.

There is another, riskier option: Make films that can sell in the West. This has been Wong Kar-wai’s strategy as he has risen to the top of the festival and arthouse circuit. But after his venture into American indie cinema, My Blueberry Nights (2007), he too has shifted toward the Mainland, reviving the Ip Man project he announced several years ago, now known as The Grandmasters. (Ironically, so great is the power of American distribution that My Blueberry Nights was probably his best-performing film in theatrical release.) Johnnie To Kei-fung has pursued several avenues at once: while making films for Hong Kong, China, and the region he has also developed audiences in festivals and in limited theatrical/ video releases in Europe and the U. S.

To the extent that the Hong Kong industry recovers, I’m happy to see it come back. I want it to succeed. Yet to the extent that it is obliged to serve the Mainland market and government policy, I feel a loss. Hong Kong films have become more “professional.” Scripts are getting tighter, and while this leads to strong entries like Hooked on You (2007) and Beast Stalker (2008), the old audacity seems rare. The success of slick, restrained items like Infernal Affairs (2002-2003) and Initial D (2005) may signal that most films will lack the galvanic unpredictability of the old days. CGI has made stunts more outlandish but also less convincing; Jackie Chan’s successors need no longer risk breaking a collarbone. A bravado bit of spfx technique, like the sculptured freeze-frame opening Dante Lam Chiu-yin’s Fire of Conscience (2010), has replaced the sort of open-throttle curtain-raiser that hurled you into the movie’s world.

In the prime days, the scale of production and the heedless rush to make movies to satisfy a market, to surpass your competitor, to make a killing before 1997—all that fostered a frantic, unpredictable churn. Fans found there the audacious conviction of the hell-for-leather outlaw. But entertaining as today’s movies can still be, the edge has blunted. Cellular (2004) became Connected (2008). Both are lively items, but did you ever think you’d see the day that Hong Kong turned out an authorized remake of an American movie? (Warner Bros. coproduced it.) Even English titles have become distressingly tasteful and cogent. Kung Fu vs. Acrobatic (1990), Love Amoeba Style (1997), Killing Me Hardly (1997), and Horrible High Heels (1996): those titles and dozens more teased us toward the sweet brink of nonsense. Divergence and Invisible Target and Wait Till You’re Older just don’t do the job.

Plastic boobs were involved

From Beijing with Love (Stephen Chow/ Lee Lik-chi, 1994).

Yet all signs of life haven’t been muffled. In the current restrictive climate, Johnnie To can make eccentric, occasionally shocking films like Running on Karma (2003) and Throw Down (2004). I take comfort in learning just last weekend what terminated Stephen Chow’s directorship of The Green Hornet. According to one report he proposed to plant a microchip in the hero’s brain and have Kato control him with a joystick. In an Entertainment Weekly article not online, director Michel Gondry claims that Chow’s plans were too far out. “Really, really crazy ideas that you would not dare bring to a studio. AIDS was involved. Plastic boobs were involved too.” That Gondry, one of Hollywood’s approved Wild Things, can find something Chow proposed over the top gives you hope.

A couple of months before the handover, I was in Kowloon talking with a cab driver. He told me confidently, “Chinese people are born capitalists. We know very well how to make money. We will never accept Communism.”

“But,” I said, “the Mainland has had a Communist government for forty years.”

He shrugged. “Forty years is not a long time.”

Now that is really taking the long perspective. Maybe I shouldn’t write finis. The prospects of Hong Kong cinema? Too soon to tell. Ask me in forty years.

Many of the statistics cited here and in Planet Hong Kong come from the Hong Kong Motion Picture Industry Association and from that invaluable source on world film trends, Screen Digest. We discuss the importance of multiplexing in the process of globalizing cinema in Chapter 29 of Film History: An Introduction. For an example of the ideological finger-wagging practiced by China’s officialdom, go here. (Thanks to Shelly Kraicer for the link.) The Michel Gondry quotation comes from Benjamin Svetkey, “Hornet’s Buzz Gets Better,” Entertainment Weekly (14 January 2011), p. 25.

PS 24 January: Soon after this entry was published, Luo Jin wrote me with some comments. I’m sorry about the delay in posting them, but I wanted to recheck my sources and dig up new ones.

I just read your latest blog entry. Some numbers are different from my knowledge, so I provide them below. I hope they are helpful.

“The number of cinema screens fell from about 140,000 in 1991 to 65,000 in 2001.”

In general the screen number in China refers to the screens in large and medium-sized cities, excluding small cities and rural areas. That is because in most small cities or counties (like Jia Zhangke’s hometown Fenyang), there is no film theater at all. And in the rural areas, only mobile screens are available. Tickets are free, so there are no B.O. receipts. In all, an accurate number of screens is hard to count. I checked the official report, and the number of cinema screens in 2002 is given as 1,581, increasing annually to 6,223 in 2010. If I am not wrong, the number in the United States is around 40,000, so it couldn’t be that much in 1991 to 2001 in China, even taking the rural mobile screens into consideration. Reportedly the rural mobile screens numbered about 40,000 in 2010.

“In 2001, box-office revenues were reported as US$77 million”

In the official report, the domestic B.O. revenue in 2001 is 890 millions RMB, equal to US$108 million by 2001 exchange rate.

My sources for Chinese exhibition statistics, as indicated above, were the annual reports in Screen Digest, which I have always found reliable in relation to other countries. I assume that the SD sources counted the rural mobile screens in the total, but otherwise I don’t know how to explain the discrepancy. Similarly, the differences in reported box office revenue may need to be checked against indigenous sources. The most recent Screen Digest annual exhibition report (November 2010) cites for 2009 34,233 screens in China (again suggesting that mobile screens are counted) and a box-office take of 6109 billion yuan, or US$906 million. The latter figure corresponds to other reports in Western sources. On screen counts, other sources suggest numbers closer to Jin’s. A 2008 Variety article mentioned that there were currently only 3000 screens in the country, while a mid-2010 Variety piece claims 5000 by 2009. If my claims prove unfounded on these points, I regret the errors.

Hong Kong Film Award winners, 2000. Among them, top row, from left: Ng See-yuen (with orchid), Carrie Ng Ka-lai, Law Lan, Andy Lau Tak-wah (white suit), Ti Lung, Cecelia Cheung Pak-chi, and Arthur Wong Ngok-tai. Bottom row: Manfred Wong Man-chun (in profile), Gordon Chan Ka-seung, Teddy Robin Kwan, Eric Tsang Chi-wai, Tung Wai, Cheung Tung Cho, Lam Kee-to (in spectacles). Thanks to Athena Tsui and Luo Jin for help in identification.

PLANET HONG KONG now in cyberspace

DB here:

Planet Hong Kong, in a second edition, is now available as a pdf file. It can be ordered on this page, which gives more information about the new version and reprints the 2000 Preface. I take this opportunity to thank Meg Hamel, who edited and designed the book and put it online.

As a sort of celebration, for a short while I’ll run a daily string of entries about Hong Kong cinema. These go beyond the book in dealing with things I didn’t have a chance to raise in the text. This is the first one. The second, a quick overview of the decline of the industry, is here. The third, on principles of HK action cinema, is here. The fourth, a photo portfolio of HK stars, is here. The following ones deal with western fandom, some Hong Kong directors, and final reflections on film festivals and a list of other intriguing movies. Thanks to Kristin for stepping aside and postponing her entry on 3D.

± 25 classics: A cheat sheet

Rouge (1988).

I have an aversion to list-making (some day I’ll explain), but I’m often asked to recommend Hong Kong movies to people wanting a quick start. So I’m launching this suite of daily entries around Planet Hong Kong by charting some widely recognized high points in this effervescent cinema.

Some items are important for their historical influence, some for their intrinsic quality, some for both. I’m restricting myself to the years after 1960, although there are several influential and powerful films before that (e.g., In the Face of Demolition, 1953). Still, if you want a fair sample of this cinema’s output you must sample these more or less official classics. If the bug bites, you can supplement them with other items that I’ll mention in passing here and in the days to come. Several of these films are discussed in more detail in the book, and most are available on DVD.

The Wild, Wild Rose (1960): Cathay (to use its shortest name) was one of the two major companies of the 1960s and in this brassy show-business drama Grace Chang (Ge Lan) had her defining role as the Carmen of the nightclub scene. Another Grace Chang classic is Mambo Girl (1957), and you can get a sense of the gorgeous star culture of Cathay by seeing her and other top actresses in Sun, Moon, and Star (1961), sort of a Hong Kong Gone with the Wind.

The Love Eterne (1963, above): This adaptation of the “plum-blossom” opera was given lavish treatment by the Shaw Brothers studio, the major studio of the period. Li Han-hsiang’s spectacle of colorful costumes, big studio sets, and gender masquerade won several awards and helped establish Hong Kong films across Asian markets. Li went on to make many other sumptuous costume pictures, as I discuss briefly here and in subsequent entries. This web essay focuses on Shaws’ anamorphic output.

Come Drink with Me (1966): The first Shaw entry in its new martial arts cycle, pioneered by King Hu. In an inn various characters in disguise meet and bluff one another; eventually the woman warrior Golden Swallow takes on all comers. Strictly speaking, King Hu’s other films belong to Taiwanese cinema, but he is one of the greatest of all Chinese directors, so you will naturally want to see Dragon Gate Inn (1967), The Fate of Lee Khan (1973), The Valiant Ones (1975), and his official masterpiece, A Touch of Zen (1971). I give him a fair amount of space in Planet Hong Kong because of his historical importance and his innovations in the aesthetics of action. I talk a little about those innovations here.

Golden Swallow (1968): Shaws’ dominant director from the late 1960s onward, Chang Cheh specialized in films of “staunch masculinity,” martial arts pictures that replaced the female-centered romances and opera films. Golden Swallow shows the woman warrior, the nominal protagonist, muscled aside by a typical brooding Chang hero—Jimmy Wang Yu, acting as if he still nursed a grudge from being The One-Armed Swordsman (1967). Later Chang developed the masculine pairing of Ti Lung and David Chiang Da-wei (Blood Brothers, 1973) and the brawny teamwork of what came to be known in the West as the Five Venoms (as in Invincible Shaolin, 1978).

Fist of Fury (1972): Child star Bruce Lee came home from Hollywood, and his first kung-fu film, The Big Boss (1971), was a sensation. The most influential star in all Hong Kong cinema, Lee stands at the center of his classics; the plots, staging, and shooting simply set off his glowering charisma. Fist of Fury provides a string of archetypal scenes: he wipes the floor of a dojo with its students and master, he kicks to splinters a sign barring Chinese from a park, and he ends his life by hurling himself, shouting, into a hail of bullets. Remade as the no less enjoyable Fist of Legend (1994) with Jet Li.

The House of 72 Tenants (1973): The success of Shaw Brothers’ export-driven Mandarin-language product led to a decline in films made in Cantonese, the local language. (Hong Kong audiences heard Bruce Lee dubbed into Mandarin.) 72 Tenants, based on a popular play, brought back Cantonese cinema in a crowd-pleasing guise. Under the direction of veteran Chor Yuen, the crisscrossed stories of neighbors became an enduring reference point for local cinema—cited again last Lunar New Year in 72 Tenants of Prosperity.

The Private Eyes (1976): Another victory for Cantonese vernacular cinema. The Hui brothers, popular from television, brought their episodic sight-gag comedy to the big screen and were among the biggest stars of the 1970s. There are many classic scenes, including Michael and Sam’s sleight of hand with candies, a shark attack in a kitchen, and a bout of chicken aerobics—plus a weird contagion of neck braces. See also Security Unlimited (1981) and, for fairly daring mockery of Beijing, The Front Page (1990).

The 36th Chamber of Shaolin (1978). As his employer Shaw Studios was fading from the scene, Lau Kar-leung (aka Liu Chia-liang) created in nearly twenty films a virtual encyclopedia of the kung-fu tradition. Any choice among the films is arbitrary (I’ll mention more in a future entry), but let this exuberant display of color, movement, and emotion stand as an outstanding accomplishment. A young man burning with rebellion enters the Shaolin monastery. Through persistence and discipline he achieves the highest distinction and returns to his home town to fight the Manchu oppressors. Featuring the director’s brother Gordon Lau Kar-fai and Lo Lieh, both martial-arts icons.

Young Master (1980): Jackie Chan’s comic kung-fu caught fire in Snake in the Eagle’s Shadow (1978) and Drunken Master (1978). Young Master is a prime instance of his rubbery energy and bottomless masochism. It benefits from extended byplay with Yuen Biao, splendid jumper, and Shek Kin, patriarch of the Hong Kong martial arts movie. Soon Jackie would show both ambition and directorial prowess in Project A (1983), his leap into big budgets and pan-Asian superstardom.

Aces Go Places (1982): The most successful franchise in Hong Kong history was launched by this jaunty action comedy, stuffed with pratfalls and high-tech chases. The buffoonery was carried off by an unruffled Sam Hui Koon-kit and a sprightly Sylvia Chang Ai-chia, not to mention the robots. Any film is improved by robots.

Boat People (1982): Ann Hui On-wah, a practitioner of serious drama for over thirty years, established her reputation in world cinema with this poignant story about a photographer’s discovery of children cast out by war. Her earlier film about Vietnamese refugees, Story of Woo Viet (1981), gave TV actor Chow Yun-fat his first major film role. Another characteristic Hui work is Song of the Exile (1990).

Zu: Warriors of the Magic Mountain (1983) Which early film by Tsui Hark to choose? The Butterfly Murders (1979) looks forward to his recent Detective Dee; the hectic We’re Going to Eat You (1980) suggests Romero turned loose in China; many critics pick Dangerous Encounter—First Kind (1980), a rough-edged Buñuelian indictment of class differences. With Zu, however, Tsui showed his resolve to update classic genres, in this case the Cantonese swordplay fantasy, using modern technique and special effects—a trend that has continued right up to the recent Storm Warriors (2010). Go here for more thoughts on Tsui.

Police Story (1985): Possibly Jackie Chan’s directorial masterpiece. A rip-roaring auto chase through a hillside shantytown, capped by a runaway bus, would be the climax of any other movie, but here it’s just for openers. The film ends with a fight in a shopping mall that, for precision and visceral impact, deserves to be ranked with the great sequences in film history. More on this scene here.

Peking Opera Blues (1986): The woman warrior’s shining hour, complete with the obligatory cross-dressing. Tsui Hark moves toward historical action/ adventure in a breathless movie that showcases three great beauties: Brigitte Lin Ching-hsia, Sally Yeh, and Cherie Chung Cho-hung.

A Better Tomorrow (1986): The film that defined a generation and cemented Chow Yun-fat’s star stature. John Woo came out of Taiwanese exile to make a film that revived the Chang Cheh spirit of brotherhood, made even more romantically doomed by the idea that Hong Kong was living on borrowed time.

Rouge (1988): A courtesan’s ghost revisits contemporary Hong Kong and finds that no one else is willing to die for love—not even the man who pledged to join her in death. Stanley Kwan Kam-pang’s delicate yet straightforward handling of the plot, refusing all special effects, gives an extra poignancy. Others would suggest Kwan’s Centre Stage (aka Actress, 1992), a biographical study of the great film star Ruan Lingyu.

The Killer (1989): The Chow/ Woo collaboration that brought them to the attention of the West. Often imitated, at home and abroad, the original retains its bold lyricism and outlandish emotion: crime and punishment as (mostly male) melodrama, accompanied by cadenzas of annihilation. To be supplemented by A Better Tomorrow II (1987), Bullet in the Head (1990), and Hard Boiled (1992), all of which brought awed fanboys to their knees.

God of Gamblers (1989): A financial triumph for bad-boy producer/director Wong Jing and the definitive gaming movie for a town that loves a bet. Shamelessly cheesy in its plot mechanisms, surprisingly elegant in its direction, the movie yanks us from laughter to pathos. Plus Chow Yun-fat in a tuxedo. To be seen alongside Stephen Chow Sing-chi’s parody All for the Winner (1990).

Days of Being Wild (1990). Wong Kar-wai’s breakthrough film about young people adrift in the early 1960s. A dazzling array of stars (Leslie Cheung Kwok-wing, Maggie Cheung Man-yuk, Andy Lau Tak-wah, et al.) creates a languid movie about the magnetic pull of selfish passion. For many local critics, the most important film of the last thirty years. I discuss a rare alternate version of the film here.

Once Upon a Time in China (1991): Tsui Hark doing Movie Brat revisionism again, this time with the Southern Chinese folk hero Wong Fei-hong. This flamboyant exercise in fervent nationalism ushered Mainland wushu champion Jet Li onto the world stage. If Bruce Lee radiated a cocky sexual energy, this film helped establish Li’s star image as a shy and chaste warrior.

Chungking Express (1994)/ Ashes of Time (1994): A coin-flip. The first showed that Wong Kar-wai could make a movie fast, cheap, and charming. The second showed that a swordplay film could be drenched in romantic longing. Both bristled with audacious storytelling tactics. Chungking spliced two stories together (prefigured in the way characters bump into each other), while Ashes zigzagged and spiraled in time, refusing plot certainties but offering a hypnotic reverie instead. Western critics and fans, notably one Q. Tarantino, sat up and noticed. PHK devotes an entire section to Chungking; go here for more on Ashes of Time.

The Mission (1999): Johnnie To Kei-fung’s stealth classic. Made on a shoestring, shot in less than three weeks (without a developed script), filled with great character actors, this ascetic polar has some of the subtlest plot twists in Hong Kong film. If Kitano Takeshi in his prime had made a Hong Kong film, it might look like this. Of course the mall shootout has become a classic.

Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon (2000): This US-Hong Kong-Taiwan project showed that the world was ready for the wuxia pian, or film of heroic chivalry. CTHD became the top-grossing foreign-language film in U. S. history. The versatile Ang Lee centered the drama on two couples, one young and one older, and their life in the jianghu–that virtual, larger-than-life world of forests and rivers that tests warriors’ righteousness. Lee’s film prodded Zhang Yimou to make the artier Hero (2003), first in a procession of historical dramas that helped revive the Mainland film industry.

In the Mood for Love (2000): Julia Roberts’ favorite movie, I’m told. Revisiting the period and perhaps some of the characters of Days of Being Wild, Wong Kar-wai evokes muffled yearning through averted glances, hidden faces, radiant costumes, and a typically spine-tingling soundtrack. This Cannes prizewinner was given a sequel, 2046 (2004), that is harsher but no less romantic in its commitment to cherishing the past.

Infernal Affairs trilogy (2002-2003): A deliberate effort to break away from the hell-for-leather action film, the IA trio showed that Hong Kong filmmakers could construct a taut, restrained crime plot. The first installment is a compact, efficient suspense exercise, the second a wide-ranging exploration of betrayal, and the third a fairly daring experiment in time-shifting and subjectivity. Many recent crime films have taken their cues from the trilogy’s huge box-office success. Portions were remade as The Departed, and for once it was the Hollywood movie that was overblown (not least the contribution of Mr. Nicholson). I set down some thoughts on the two versions here and here.

Kung Fu Hustle (2004): Stephen Chow purists may consider it a case of comedic elephantiasis, but this big-budget extravaganza is historically significant for winning worldwide distribution and big box-office. Kung Fu Hustle is also packed with engaging CGI-enhanced gags, on every scale from tenement demolition to cobra-smooching. One of the funniest scenes will encourage you not to use the phrase “hair on fire.” The even more inventive Shaolin Soccer (2001) was Chow’s previous step toward making movies at once China-friendly and globally marketable; not for nothing is his company called The Star Overseas.

Later this week I’ll offer a list of other Hong Kong films that I think are worth attention. (So wait until you’ve seen all my picks before writing me to point out titles I’ve omitted here!) And somewhere I’ll try to wedge in some outstanding sequences. This is nothing if not a cinema of rousing set-pieces.

Nearly all the films I mention are available on DVD, with European and American editions usually being of superior quality to Hong Kong editions. Many of the filmmakers mentioned are discussed in other entries on our site; check the Directors category on the right.

In 2005, Chinese critics assembled a list of the 103 best films from the PRC, Taiwan, and Hong Kong. That list can be found here.

PS 3 Feb: Another list of top Chinese films, tilted somewhat toward Taiwan, is here.

A Better Tomorrow (1986).

Direction: Come in and sit down

Tampopo (1985).

There is what we call the Hollywood Style. . . . . Master shot [filmed] from the very beginning [of the scene] to the end, then a close shot from beginning to end, then from angles A and B, cutaways, et cetera. Then all of the materials are assembled later in the editing room. But in Japan, the editing plan is prepared before shooting. When you cut, it’s a matter of trimming heads and tails and just putting it together. Three days after the end of filming, there is a rough cut of the film.

Itami Juzo (The Funeral, A Taxing Woman).

DB here:

Planet Hong Kong 2 still on the way…. very close to ready…. deciding among cover designs…. soon; sooner if possible….

In the meantime, some creative choices involved in directing a simple scene.

Shanghai’d

What could be easier than getting a man into a room and sitting him down? The opening scene of Shanghai (2010) seems to me to bungle this basic piece of tradecraft.

In the image above, journalist and spy Paul Soames is being beaten up by the minions of Captain Tanaka. Who’s the poor sod who has to hang those big flags so high in movie torture chambers like this? Anyhow, soon the torturers drag Soames up the stairs, likewise in long shot, to meet the captain.

A brief shot of a door opening seems to put us in Soames’ shoes. But that viewpoint isn’t carried through consistently: we cut abruptly to the other side of the door, to a long-lens medium shot of Tanaka opening it.

Soames steps forward and is greeted by Tanaka.

Now comes the establishing shot, from quite far away, as Soames walks to the desk. This shot is interrupted by cutting back to the shot of Soames moving forward.

As the shot continues, Soames sits down and looks up. Throughout the scene, this setup will be assigned to cover Soames, with the camera panning and reframing as necessary.

Counting the swinging-door shot, it has taken four shots to get Soames into the room. But the actors aren’t yet fully in place. As Soames turns his head, Tanaka (back to master shot) moves around on Soames’ left side. The phone starts ringing.

Tanaka begins to halt at his desk, but before he stops moving we cut again to Soames, whose attention has shifted to the phone. He has asked that his embassy be notified, and now he suggests that it’s the embassy calling.

Cut to a close-up of the telephone, the object of Soames’ attention, and another shot of Soames, as before, as he looks expectantly back at Tanaka.

Now we have a closer shot of Tanaka, still slightly moving, and we catch his disdainful expression.

After Tanaka lifts and drops the receiver to cut off the call (another close-up), he settles into place. The rest of the conversation is played out in those loose over-the-shoulder shots that modern directors like so much.

Throughout, the shots of Soames seem to be from the same camera setup as when he entered. No repositioning of the camera marks stages of his part in the conversation, though at the end of the scene a pair of close-ups shows Tanaka asking, “Where is she, Mr. Soames?” Cue the flashback.

It’s not just that it took director Mikael Håfström over a dozen shots to get Soames and Tanaka into position for their central duet. Hitchcock might use several shots too. But each of his would be calibrated for specific expressive effects, such as subjective point-of-view treatment or a striking composition. Instead, the Shanghai shots exemplify a fairly casual cover-everything approach–a scattergun version of what Itami called the Hollywood Style.

Here the individual shots make a big deal out of a simple piece of business. We don’t need to see all of Tanaka’s office (since the rest of the space never gets used in the scene), and it doesn’t need to be so vast in the first place (except to announce that this is an expensive movie). The long-lens camera setup that lets Soames advance into the room and sit exists solely to let us watch the actor act, and it provides awkward cuts when bits of it are embedded in extreme long-shots.

It’s not hard to imagine alternatives. A straightforward tracking back from Soames as he enters and sits, framed from further away, would have kept both him and Tanaka in the frame. This framing could have easily shown Tanaka coming around to take up a position in the foreground by the desk, perhaps turned partly toward us so that we could peg him as a major character. Then if you insist on a cutaway to the ringing telephone, it would have had more impact, interrupting a sustained shot and contrasting to the fuller frame showing the two men.

Today many directors believe that we must always see the face of the person who’s speaking. So we get lots of shots, mostly singles, one per line, and each face is usually in close-up or medium-shot. Hence the great number of cuts per scene; here, counting from the swinging door, we get 23 shots in 97 seconds. And hence the repetitive reverse shots that cover the conversation.

I’m not the only one who notices these things. “If I see another over-the-shoulder shot,” says Steven Soderbergh, “I’m going to blow my brains out.”

Television probably has a lot to do with the emergence of this style, as some historians, me included, have argued. You have to be a good director to overcome the choppiness inherent in this manner of filming. I don’t think that Hafstrom did that. If the director had planned his shots in the finer-grained way Itami indicates, we might have had more visual variety, along with compositions and cutting that take us beyond the actors’ faces and line readings.

Dandelion soup

Now we might look at how Itami does it. An early scene of Tampopo (1985) also demands that a man, along with his sidekick, come into a room and sit down. We see Goro the trucker and his pal Gun enter the noodle shop, along with the little boy they’ve found lying on the street. We see them first from outside and then from inside the new locale, much as in our Shanghai example. But there’s no need for anything like that insert of the opening door.

Cut to a point-of-view shot that makes a point: Goro is entering a room full of thugs. Itami pans to show two knots of men in the shop, some of them threatening.

While each Shanghai shot does one thing at a time, this shot does two things at once. This shot sets up the hostilities that will ensue, while also laying out the space of the shop and positioning all Gun’s adversaries in it, along with the proprietress Tampopo.

Cut back to the men at the door, but it’s a different framing, from further back, than we saw initially. Now some of the thugs are staring at our heroes.

Itami is calibrating his compositions to give us new information. If this composition had been used for the first shot of the men entering, the subjective pan across the room wouldn’t have been so surprising. Now the camera cranes back to follow Goro and Gun striding to the middle of the shop and sitting down. They order bowls of noodles.

This orientation will be the dominant one in the course of the scene. But the space isn’t as bare as in the Shanghai scene; the men we see dotted around the room will play important roles in the action now and later. As in the Shanghai scene, there are cuts to close-ups, but they show more informative items than a ringing telephone. One shot picks out Tampopo herself (establishing her as a major character), another picks out Gun’s skeptical view of her cooking technique, and a third tilts down to show her hands cooking noodles in water not yet boiling.

To the noodle connoisseur Gun, this proves that she’s a maladroit cook, and another shot of the two men shows his reaction.

Cut to a long-shot. The long-shots of the office in Shanghai are always from a single position (the result of straight-through master-shot coverage), but here we get a slightly different framing than we’d seen earlier. The camera is somewhat lower, which allows Itami to stage a little piece of business. Tampopo’s son Tabo runs unseen out from behind the young thugs, along the aisle behind the stools, into the foreground, and out frame right. He has been beaten up outside, but Tampopo takes it in stride.

When Tabo has gone, the men resettle in for the next phase of the scene, when Tampopo serves Goro and Gun. The entire shot we’ve just seen is held for forty-one seconds. Soon a fight will erupt, delaying the revelation of how awful Tampopo’s noodles are.

This is not virtuoso direction, but it is smooth and precise. Each shot blends with the next with a degree of care we don’t get in the Shanghai instance. That’s partly because each shot is given its own small, completed arc of action. (The nine shots I’ve listed run ninety seconds.) For example, Tabo’s run down the aisle is prepared by a slight shift in Goro’s glance at the end of an earlier shot I’ve mentioned. He looks toward the door and tells Tabo he’ll catch cold.

This moment prepares us for the next bit of action, while also setting up the trucker’s gruff concern for the boy, an important element of the plot to come.

More generally, across the whole scene each long shot does more than simply orient us or cover changes in position; it’s enlivened by movement and incident. Nothing in the Shanghai scene approximates Itami’s willingness to let body language replace facial close-ups. Here Goro coolly samples the noodles while the gang prepares to rumble.

Later, an entire scene will be played in a packed long shot lasting nearly a minute. Goro has brought Tampopo to watch a master chef at work, and Itami is perfectly okay with concealing her face as she calls off all the orders that people have just made. We don’t need a close-up of her expression when she speaks; the important thing is her aptitude and the customers’ enthusiastic applause.

An unassertive shot like this, you want to say, respects the audience by letting us see everything that matters at each moment. We call it directing a movie.

Itami’s remarks in our epigraph come from Bob Strauss, “Director Juzo Itami,” Premiere (June 1988), p. 25. Soderbergh’s comment about OTS shots is taken from “Matt Damon: Steven Soderbergh really does plan to retire from filmmaking,” at the Los Angeles Times.

Shanghai has probably not come to a theatre near you. Delayed during the shooting, it sat on the shelf for some time before its premiere last summer in China. It’s announced for U. S. release in 2011 but the Weinstein company website says only that it’s “coming soon.” Planet Hong Kong redux will beat it, for sure.

As chance would have it, Tanaka in Shanghai and Gun in Tampopo are both played by Watanabe Ken.

My arguments about the emergence of this “intensified” version of classical continuity are made in The Way Hollywood Tells It, pp. 117-189. I’ve done a blog on the idea here; it’s hardly fair for me to compare Nora Ephron with Lubitsch, but she sort of asked for it. For more on economical staging and cutting, see our entry on Spielberg’s shooting style, as well as the idea of the Cross. For another comparison of Hollywood direction with an Asian alternative, see our entry on Jackie Chan’s Police Story.

A. D. Jameson makes strong points about inefficient shot breakdown in his essay “Seventeen Ways of Criticizing Inception.” Jameson invokes The Ghost Writer as a good counterexample, and indeed Polanski’s film often displays the sort of cut-to-cut restraint and control that Itami calls for. Jameson elaborates further in another epic post. There’s also an intriguing discussion at Jim Emerson’s Scanners blog of how much a filmmaker should rely on close-ups; the film at hand is Black Swan.

P.S. 5 January 2010: We’ve had an enthusiastic response to this entry; thank you, Twitterers. It occurred to me that readers might be interested in a similar comparison between Asian filmmaking and U.S. practice in a very early entry, back in 2006. Ironically, Soderbergh’s Good German was involved, the subject of an earlier post. The contrast case was Johnnie To’s PTU.

Shanghai (2010).