Archive for March 2011

Observations on Filmart (This is not a typo)

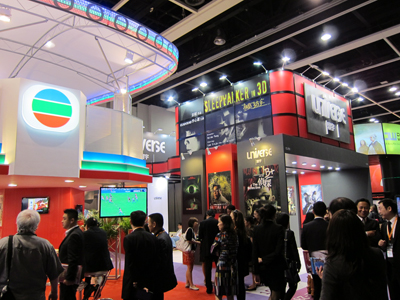

A modest display at Filmart, Hong Kong Convention Centre.

DB here, channeling an apparently apocryphal Soupy Sales line:

Kids, what starts with f and ends in art? No, not that. It’s Filmart, the annual trade gathering that kicks off the Hong Kong Film Festival. Add a space and a capital, and you have the main title of one of our books. Sometimes accidental cross-promotion can work out pretty well, as you see above.

Seriously, though, Filmart is a wonderful event. It includes an opening ceremony to launch the festival, the Asian financing forum known as HAF, the Asian Film Awards (covered a bit here), and a teeming meet-and-greet that sponsors panels, lunches, and hundreds of booths that allow media buyers and sellers to get together. I’ve covered Filmart in 2007, 2008, 2009, and 2010. Here are some comments and images from last week’s edition.

The shebang started with the ceremony introducing some of the opening films and their stars. Here the Filmart’s official hostess, Miriam Yeung, is about to go onstage to greet the audience.

And here at the ceremony are the three stars of Don’t Go Breaking My Heart, Gao Yuanyuan, Daniel Wu, and Louis Koo.

Ho Yuhang’s clever neo-noir Open Verdict was a highlight of the shorts collection Quattro Hong Kong 2. Here he is with his star, the radiant Kara Wai Ying-hung, Shaw Brothers action queen and star of both Open Verdict and Ho’s earlier feature Daybreak.

Filmart’s main business takes place in a vast hall, with companies’ displays lined up in rows and along aisles. Most firms have fairly modest stalls, but others are flamboyant, like these big boys for Mei Ah and Universe, two long-established Hong Kong production/ distribution companies.

But the place isn’t so big that you can’t run into old friends, like Margaret Pu (far right) and her colleagues Jack Lee and Dan Zhu from the Shanghai Film Festival.

More movers and shakers: Patrick Frater, CEO of Film Business Asia, and Peggy Chiao, producer (Trigram Films) and doyenne of Taiwanese New Cinema.

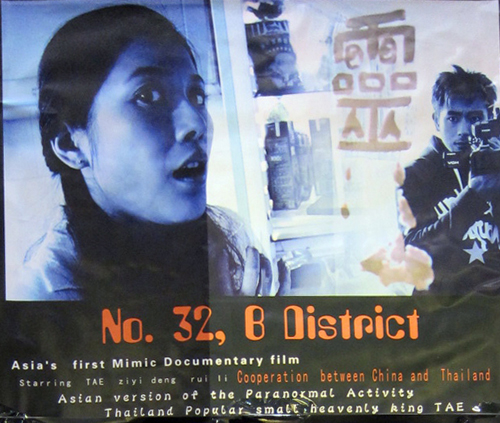

At Filmart one can always find some unclassifiable items, as witness the project pictured at the very end of this entry.

New Action on the Mainland

Most panels ran opposite film screenings, so I usually plumped for the movies. But I did attend an intriguing session on “Beyond Box Office: China: The World’s Largest Developing Market.” Sponsored by the Hong Kong Film New Action committee and moderated by Shanghai media executive Bill Zhang Ming, the panel included many Chinese figures and the American Ted Perkins, who has worked for both Warners and Universal and is now serving as executive VP of production for IDG China Media.

Some of the themes discussed echo things I talked about in the added chapters of Planet Hong Kong, but I garnered some new information as well.

*Several panelists pointed out that the stupendous growth in the Chinese box office, over 50% each year, demands that many new cinemas be built. The major cities have now got a good supply of screens, but now the third- and fourth-tier cities need to have more screens. Some commentators spoke of a “new five-year plan” aiming to upgrade and increase the nation’s screens.

*As in America and other countries, a few films typically garner the lion’s share of receipts; one panelist estimated that 80% of income stems from 20% of the films. For the foreseeable future, the big films, from China or the US, will drive the market.

*The growth of the market is even more remarkable given the comparatively small audience (around 20 million, one panelist surmised). Average ticket price is 32 renminbi, or about US$4.88.

*Hong Kong remains essential to the mainland market but also vulnerable. Films with local stars and directors can succeed, and Hong Kong is a key site for financing and packaging projects. But purely local films will remain low-budget items; the bigger films will be mainland co-productions, with some PRC talent and scenery on the screen.

*The popular audience, according to screenwriter-producer Qi Hai, is driven by female tastes: date movies are chosen by the woman, and family films are picked by mothers.

*Ted Perkins pointed out that although recent growth is good for all players, in any film industry there are always more funds in production than can be recouped overall. There will be winners and losers, especially if there’s an overabundance of production, as there currently is on the mainland. Although about 500 films were produced last year, more than half did not find theatrical release or screen in the best cinemas. (Panelists’ estimates of unseen or underseen titles varied from 250 to 400.) Marcus Lim provides a comparable set of figures.

*Some panelists opined that the market lacks directors and stars who are likely to provide success. One panelist estimated that only half a dozen directors have strong track records, and only one star, Ge You, can guarantee an audience.

*Most panelists agreed that 3D was not viable for most films, but in China the new format can help the business in an unusual way. Historically, most mainlanders couldn’t afford going to films, so they aren’t in the habit of attending theatres. They watch films on video or on the Net. Curiosity about 3D may attract new cinemagoers, “educating” spectators to the pleasures of seeing movies on the big screen.

*Most big countries have a well-structured pattern of “windows,” whereby a film moves from the theatre to video, cable, and online. But in China, the expansion of screens is occurring simultaneously with the growth of online distribution, with the danger of piracy. The Chinese will have to come to grips with decisions about pricing and more stable windows.

Seldom do we have a chance to realize that we’re witnessing a historic change in the global film industry. The rise of China is such an event, and film historians should be watching the unfolding process closely.

Changing the film ecology

The Jockey Club Cine Academy, formed last summer, is an educational enterprise guided by the HKIFF Society and funded by the Hong Kong Jockey Club Charities Trust. It’s a three-year program aiming to increase film literacy among young people. The Academy held a major event during Filmart, a nearly three-hour master class with Jia Zhangke, director of Platform, The World, Still Life, and most recently I Wish I Knew. High school students made up a large part of the audience.

Researcher and editor Wong Ain-ling (above, with Jia) interviewed him about his career and then opened things up for questions. Here are a few points Jia made.

*His recent turn toward documentary filmmaking isn’t a new development for him. When he was starting out, documentaries were the most dynamic part of the PRC film scene. Although the films captured aspects of contemporary life ignored by mainstream movies, they were seldom watched by audiences. So the question for Jia became: “How to change our film ecology?”

He has used a documentary project to spark a fiction feature. In Public (2001) became a draft for Unknown Pleasures. Jia enjoyed eliminating dialogue and narration from his documentaries, relying on peoples’ faces and situations to convey ideas. Critics complained that documentarists couldn’t tell stories, but he wanted mainland audiences to learn to find the latent emotions in the scenes, the “poetic” side of realistic cinema.

*His early films incorporated popular music, including Taiwanese tunes sung by Teresa Teng. Why? During the 1980s and 1990s, mounted loudspeakers broadcast a lot of Mandarin pop songs, making this music just part of a city’s ambience. This was something he exploited in his first feature, Xiao Wu.

*Jia had arguments with censors on his first three features, and those films weren’t widely seen. But in 2004, the censorship system changed, mostly for the better. Yet distributors still block films shot on video from being shown in cinemas, creating what Jia called a “technical censorship.”

*The reports are true: He is making a martial arts film with Johnnie To’s Milkyway firm. Jia wants to examine the imperial system in the period around 1900. He would like to follow it with another historical film, this one about Hong Kong in 1949, centering on two characters, a Communist and a KMT Nationalist.

Like Hong Kong itself, Filmart has a pulsating energy and offers an overwhelming array of choices: you can watch movies, attend events, and just gawk. You must run to keep up. That’s as it should be.

For more coverage of industry doings at Filmart, see Liz Shackleton’s rundown at Screen International (may be proprietary). Another story in Screen International mulls over the prospect that China could fairly soon become the world’s biggest market. See as well several items at Film Business Asia, particularly Stephen Cremin’s article on Chinese coproductions. For our takes on some Jia Zhangke films, you can go to this category.

PS 31 March (HK time): I should have mentioned what the New Action panel did not: Piracy. The LA Times has a good recent article on DVD bootlegging in the PRC, raising the crucial factor I’ve heard mentioned as well: the role of the People’s Liberation Army.

Splashy and spare, vengeance and regrets

DB here at the Hong Kong Film Festival:

Above, a tourist pic, the view from one of several escalators in the towering mall in Langham Place. Its flamboyance makes a sharp contrast with the movie I saw in the mall’s cinema, the minimalist Turin Horse. (See below.) The very end of this entry presents another view from the heights of Langham.

Righting wrongs, with new wrongs

Heaven’s Story.

Most Hong Kong thrillers and action pictures use revenge as their mainspring. It’s fairly uncommon, however, for a film to try to convey the cost that vengeance exacts on the avenger. Punished, directed by Law Wing-chong and produced by Johnnie To, makes an effort in this direction. A mogul’s spoiled daughter is kidnapped, and his refusal to bend to the captors’ will leads one, in a moment of pique, to kill her. After learning of her death, the mogul contracts with his chauffeur, a man who knows the underworld, to track down the gang.

The tycoon, played by Anthony Wong, goes through some agonizing as he must hide his daughter’s death from the girl’s stepmother. In turn, the chauffeur, Richie Jen (whose skilful performance dominates the movie), must abandon his son after executing the boss’s revenge. The men’s lives dissolve in their quest for payback, and the fact that the daughter, a brattish cocaine addict, is completely unsympathetic only makes the whole thing bleaker. An obvious parallel is the Eurothriller Taken, which presents a rash but innocent daughter rescued by a father who remorselessly cuts down everything in his path. Well-mounted, with perhaps too many flashbacks, Punished is that unusual Hong Kong film that insists that every effort to assuage male pride takes a toll in male pain as well.

But for a film that really investigates the cost of settling accounts you have to turn to Heaven’s Story. Here Zeze Takahisa, known mostly for erotic films, traces out the consequences of three killings. The cop Kaijima impulsively shoots a suspect. The locksmith Tomoki’s wife and child are brutally murdered by a teenager, Mitsuo. And elsewhere the little girl Sato is the only survivor of another family homicide.

The stories link up. Sato, in numb grief, sees Tomoki on television vowing to kill Mitsuo when he leaves prison. Because the man who killed her family has committed suicide, Sato embraces Tomoki’s reckless vendetta. She grows up hoping to help him kill Mitsuo. At the same time, Kaijima’s son develops a sidelong relation with her….

I really haven’t given away much, because the film traces these characters and several more across the space of—yes!—four and a half hours. As in a novel, the motives and connections among characters emerge slowly. Zeze’s plot maintains a balance between suspense about what comes next and curiosity about the past. And as in most network narratives, part of the pleasure is wondering how the new characters we meet will tie into the ramifying web of relationships.

Zeze splits the film into two “acts,” with intermission, at a bold spot: ending the first part on a pitch of suspense and starting the second with a new set of characters, making us wait for the developments set up at the end of act one. Working on a broad canvas allows the film to shift majestically, in large blocks, from one person to another. The same goes for the ending: After the main drama is resolved, Zeze allows a long epilogue in which many of the film’s motifs are gently set to rest.

That drama and those motifs, unsurprisingly, bear on the power of unspeakable acts to ignite our desire for revenge. Every character, even those unaware of the savage deaths in the past, is altered by the central killings. An amateur rock singer, a young woman almost defiantly self-centered, becomes a devoted mother, which seems to yield some hope; but her family is eventually shattered by echoes of Mitsuo’s crime.

Those more directly affected by the killings face more severe tests. Kaijima, for instance, tries to compensate for his impulsive shooting by giving monthly money to the victim’s wife and daughter. (The irony is that the money comes from his sideline, moonlighting as a paid killer.) The daughter grows up expecting Kaijima’s payments as her due and tries to extract more money from him, as if he were her surrogate father. This daughter, along with Mitsuo the teen murderer and the older woman who takes him in, come to unexpected prominence as the film unwinds a tale of sorry lives and compromised choices.

Mostly shot in rough-edged, somewhat bumpy shots, Heaven’s Story at first made me fret: 278 minutes of this? I needn’t have worried. The pace is steady, even relentless, but I didn’t find it monotonous, and a more polished presentation might have lacked the distressed urgency of what we get. Incidentally, the framing bits, showing a sinister puppet play with Shinto overtones, are filmed with smooth care. The contrasts in technique suggest that a more serene supernatural domain exists alongside the anxious sphere of human desires, where people persist in trying to redress old sins by committing new ones.

The obscurity of the everyday

A horse is feverishly hauling a cart, the camera riding low underneath the beast’s plunging head. The wheezing repetitive score rises to a scraping whine, then it’s replaced by the sound of fiercely whipping wind. The old driver pulls the cart up at a farmhouse, where he’s met wordlessly by a younger woman. As the wind tears at them, they take the horse to the barn, the cracked leather harness left on the cart. Inside the cottage, the woman helps the man change his clothes. The woman boils a pair of potatoes. She says: “It’s ready.” It’s the first line of dialogue, and it comes nineteen minutes into the film.

Thus begins the festival film that has exhilarated me most so far, The Turin Horse. With this movie, Béla Tarr, a favorite of mine (especially here, but also here and here), has given us his most spare entry yet. Almost nothing dramatic happens during its 140 minutes, and what does take place is opaque and enigmatic. The film refuses traditional exposition, forcing us to observe bits of behavior and speculate on why things unfold this way.

At one level, it’s the heritage of Neorealism paying off. In Umberto D’s scene of the housemaid preparing breakfast, we had an early example of sheer dailiness used to characterize a person and a milieu, as well as to absorb us in what we might call mundane beauty. But something different, more abstract and disturbing, happens when a film is nearly all routine. In the farmhouse, the old man and his daughter eat their steaming potatoes barehanded, squeezing and mushing them. He wraps himself in a blanket and stares out the window while she does household chores. Next day they arise, dress, and hurl themselves again into the blasting wind. (The wind ripping along the wet streets in Sátántangó is nothing compared to this gale.) In all, cramped settings observed with Tarr’s usual tactile detail, rendered gorgeous in black and white, become as obscurely allegorical as the magical tabletop in Tarkovsky’s Stalker.

Other characters show up eventually. An hour in, a talkative friend arrives and provides a monologue cursing the ignoble forces that have driven intelligence from the world. Later some travelers appear outside at the well, with malevolent results. And the horse refuses to be fed. Perhaps at bottom the “story arc” is that light simply goes out of this world. Having dwelt on gestures (hands pouring out alcohol or struggling to harness the horse) and textures (the ripples of woodgrain on the stable door), the film slides into darkness. The motif is announced in the cryptic trailer for the movie.

From Tarr’s comments we learn that the man is a carter and the woman is his daughter. The film’s voice-over prologue invokes an episode from the life of Nietzsche, who once tried to stop a driver from mercilessly whipping his horse. The incident purportedly led to Nietzsche’s descent into insanity. Tarr has said that the film, based on a short story by László Krasznahorkai (who also wrote the novel Sátántangó), tries to imagine what happened to the horse after the incident.

Yet the horse is less important in the film than the carter and his daughter. It’s not hard to see them living a post-Nietzschean world, and the visitor’s rant about universal debasement may offer support for this interpretation. It’s another exercise in what an earlier entry called Tarr’s “postlude” vein, presenting what remains of life after history has more or less ended. Yet these are no stick figures in a metaphysical meditation. Virtually without psychology, father and daughter are defined through their sheer physical weight and movements. They confront the blasted landscape when they pass outside and the wind tears at them, but once inside they shift to the window to watch. The image of an observer trying to understand a harsh, senseless world beyond the walls is one we’ve seen in the opening of Perdition, and in the scene in which the obese doctor in Sátántangó planted at his desk tries to write down everything he sees happening outside.

Not that the cottage is any more welcoming. Splendidly filmed from a constrained variety of angles, the cottage seems bare of love, meaning, and what we normally consider drama. Tarr’s camera movements and the solemn rhythms of his shots (I counted only 37, including intertitles) are coordinated with the pace of the characters. Perhaps not since Dreyer’s Ordet has the lumbering pace of country life, the trudging gaits and reluctant effort to rise after sleeping, been rendered so expressively. Here, however, nothing is touched by grace

Tarr makes his inhospitable world spellbinding. I’m ready to watch the The Turin Horse again, even, or especially, if it proves to be Tarr’s last film.

For a detailed, less sympathetic review of Heaven’s Story, see Peter Debruge’s piece in Variety. Suggesting that The Turin Horse will be his final film, Béla Tarr discusses it here. At The MUBI Notebook, David Hudson has provided very informative coverage of the controversy around Tarr’s place in Hungarian cultural politics. For an interview with Tarr’s cinematographer, as well as a sensitive appreciation of the film, see Robert Koehler’s piece in the new Cinema Scope.

A view from Langham Place shopping mall, Mongkok.

A new book, more or less accidental

DB here:

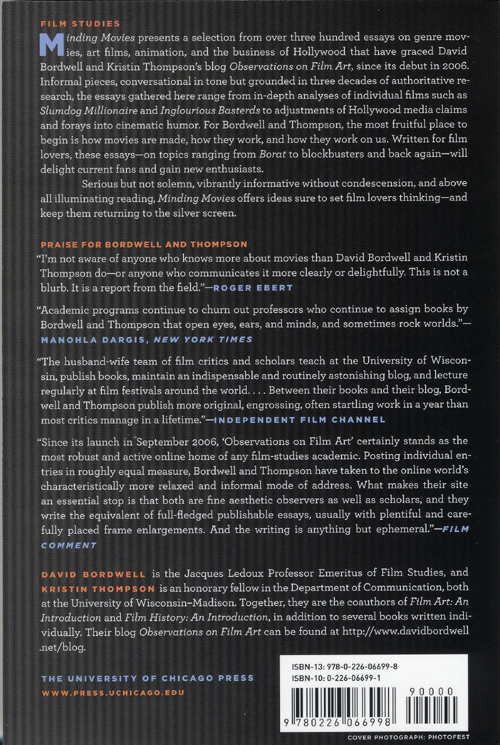

It’s a pleasure to announce that our book, Minding Movies: Observations on the Art, Craft, and Business of Film, has just been published by the University of Chicago Press. In some ways, it’s a conventional academic item, since it collects revised versions of published essays with postscripts updating the contents. But it’s also unusual, because those essays were published not in journals or magazines, but on the internet, on this very site. And they remain available online even as the book comes out.

Why do this? After consultation with our editor at Chicago, Rodney Powell, we thought it would be worth trying. Rodney and John Tryneski were kind enough to suggest the possibility of such a book, and the Press has been something of a pioneer in this new genre. For one thing, a collection allows us to single out and recast pieces that typify what we try to do—to explore films and filmmaking in more depth and breadth than most websites do. Moreover, the site has become vast; at the end of February we posted our 400th entry. We surmise that many readers would prefer a selection of pieces that give the flavor of our ways of thinking. Just as important, publishing a batch of web essays in book form is an experiment we agreed was worth trying. Perhaps this way our sallies would find a new audience.

Minding Movies is one more step in our exploration of the ramifications of web publishing. In less than five years, two net novices have published at least half a million words online. To my surprise, this experience has changed how I think about research, publishing, and intellectual work in general.

From the beginning, this site was something of an experiment. I wondered certain things. Was our research of interest to people outside the realm of college film studies? Could we attract that wraith, the Intelligent General Reader? Could we adapt our methods of working and writing to the medium of the Internet? Do you write differently for scrolling rather than page-flipping? Can you master an informal style after forty years of academic harrumphs?

Back at the turn of the millennium, I started a modest website consisting simply of my vitae and a programmatic statement about studying film. Later I mounted essays that supplemented my books as they were being published. The site expanded slowly, adding two or three online essays a year. In late September of 2006, in response to a suggestion by an anonymous user of our textbook, Film Art: An Introduction, we launched a blog, which we added to my original website. At first we posted every few days, but in later years we typically have written one entry every week. When we visit film festivals, the pace picks up.

We haven’t neglected the website, though. There we have republished published essays and items from out-of-print editions of Film Art. Eventually we put up the entirety of Kristin’s 1985, long-out-of-print book Exporting Entertainment. The combination of the original site and the blog gradually became a fairly monumental thing.

In part, the blog was an effort to amplify and extend the work of our textbooks, particularly Film Art. Hence the site was originally called “Observations on film art and Film Art.” But rather quickly the blog took on a life of its own. For me, as a recent retiree, it has become something of a substitute for my teaching, a way for me to try to communicate my ideas, old and new, to a receptive audience. The site, blog plus essays, functions rather like a self-published magazine, in which we can write about whatever we find curious or compelling in the world of cinema.

We found that our research has proven of interest to a surprisingly large audience. Last week, the site’s total lifetime pageloads surpassed three million. We have had nearly two million unique visitors and almost half a million returning visitors. So far this year, we’ve been very encouraged by the attention given to Kristin’s two entries on the prospects for 3-D (here and here), my entry on eye behavior in The Social Network, and above all Tim Smith’s guest blog on his eye-scanning experiments. Tim’s striking videos were downloaded, from our site and others that picked them up, over 720,000 times in ten days.

What about our working and writing methods? Could we adjust to the constraints and opportunities of the Net? Here the main arena was the blog. It began with festival communiqués from our ever-popular destination, Vancouver, but shortly it turned into something else. The occasion of a screening or lecture spiraled into a consideration of more general issues. A philosophers’ conference teased me into trying to explain some aesthetic questions that had relevance to film. The release of The Departed led me to reflect on some broader aspects of Scorsese’s career, with results that some readers took issue with.

Rather soon, however, we no longer needed the nudge of an occasion to provoke an entry. Kristin took the initiative by writing an essay about how to understand box-office figures—something that students should know but that would also be of interest to any filmgoer. Shortly occasion-based entries mingled with long-form essays on topics as varied as contemporary Danish films and first shots in movies. Sometimes the essays developed ideas we’d argued for in published work (such as my endless invocations of the idea of “intensified continuity” style), but no less often the blog encouraged me to try out new ideas. The format now seemed to me a perfectly reasonable outlet for fresh research, as with my studies of William S. Hart and a long piece on flashbacks.

The experiments continued. Most of our books rely on arguments developed through frame enlargements from particular scenes. So we learned how to illustrate our online essays with frame grabs, which yielded the bonus of color. The next step was obvious: books. The University of Michigan had already made my Ozu and the Poetics of Cinema available as a pdf. After Planet Hong Kong went out of print, I had the chance to create a wholly digital second edition. I look forward to publishing my next books as electronic editions.

In 2006 I could never have predicted the complementary developments in our online work this year. A book originally printed gets new life in digital form. Essays originally online are now available in book form. Where it all leads, we don’t know. But it looks like more fun is ahead.

KT and DB learn about kiwis in Rotorua, New Zealand, 2007.

Kristin here:

We had never created a book so quickly. Our neighbor Jim Cortada, a professional writer, calls Minding Movies a “free book” because it consists of material already published.

Of course, we had taken a lot of trouble over the entries during the preceding few years, but not with the intention of ever seeing them printed. Some we turned out quickly in response to something intriguing or silly or downright wrong that we saw on the internet. Those usually involved little more than looking up a few dates or names and coming to some conclusions about the issues involved. Others required days of research, with stacks of clippings and print-outs and piles of books with Post-its sticking out of their pages. Some entries involved the kind of intensive research that we would formerly have put into an article destined for an academic journal or anthology.

We wound up writing many entries that we didn’t think of as being as ephemeral as most web publications. The effort involved in keeping the blog going, though it happens in short bursts, does add up to a lot after four and a half years. (Collecting the many illustrations needed for some entries takes more time than the writing.)

David wants to explore the possibilities of online publishing, and I must say that having Exporting Entertainment, which was in print for a very short time, available again is satisfying. Still, if I believe something will be worth reading in years to come, I prefer hard print. So the opportunity offered by the University of Chicago Press to publish a selection from the blog was most welcome.

Choosing the entries to include wasn’t easy. Some of our most popular and substantive essays were the close film analyses. Yet those were precisely the ones which, as David says, web publication enabled us to use many illustrations. For print publication, we were more constrained, and for the most part we avoided those essays rather than publish them with only a few of their images. We selected a small number of the more heavily illustrated items: “Grandmaster Flashback,” “Unsteadicam Chronicles,” “Pausing and Chortling: A Tribute to Bob Clampett,” “Slumdogged by the Past,” and “A Welcome Basterdization.” To make up for such profligacy, we balanced those with entries that needed one or two or no illustrations.

We hope the result reflects some of the variety and range that the blog as a whole contains. One thing we discovered is that when you’re blogging, the kinds of things you’re inspired to write about far outrun the academic topics one chooses for formal articles in print. There’s also the chance to be topical in a way that the slow process of academic publishing doesn’t permit. And quite often writing for the blog can indeed be fun.

In a way we are following in the model of our friend Roger Ebert, who took to internet writing like the proverbial fish to water. Especially after the loss of his voice, he has reached an even greater and more devoted audience with his reviews and his reflective, often moving essays posted as Roger Ebert’s Journal. Roger has supported our blog enormously by linking to and/or tweeting about some of our entries. He now has supported the book by providing a more than kind blurb for the cover. The book is dedicated to him and his wife Chaz. A month from now, we look forward to blogging from the thirteenth annual Ebertfest.

For the blog goes on. Even if Minding Movies attracts favorable notice and sequels become possible, we’ll never catch up in print to what we’ve done on the internet. After all, no book is really free.

Milkyway’s fine romance

Don’t Go Breaking My Heart.

DB here, from the Hong Kong Film Festival:

First, news. The Asian Film Awards, presented in a glitzy ceremony Monday, held some surprises. Confessions from Japan and Let the Bullets Fly from the Mainland (discussed in my previous entry), each had six nominations going in. But Confessions nabbed no prizes and Bullets won only for Best Costume Design, the award going to William Chang Suk-ping, probably best known as a versatile collaborator with Wong Kar-wai.

Best Picture winner was festival favorite Uncle Boonmee Who Can Recall His Past Lives, by Apichatpang Weerasethakul (right, in remarkable suit). The Best Director and Best Screenplay awards went to Lee Chang-dong for Poetry (which Kristin and I had liked very much at Vancouver). The winners are picked not by a mass of voters, as with the Oscars, but by a jury drawn from industry figures, critics, and festival executives. The first year’s awards in 2007 was dominated by the crowd-pleasing monster film The Host, which garnered four prizes, but this time two top honors went to arthouse/ festival titles. Still, it was very nice that local industry mainstay Sammo Hung got the Best Supporting Actor kudo for Ip Man 2.

Best Picture winner was festival favorite Uncle Boonmee Who Can Recall His Past Lives, by Apichatpang Weerasethakul (right, in remarkable suit). The Best Director and Best Screenplay awards went to Lee Chang-dong for Poetry (which Kristin and I had liked very much at Vancouver). The winners are picked not by a mass of voters, as with the Oscars, but by a jury drawn from industry figures, critics, and festival executives. The first year’s awards in 2007 was dominated by the crowd-pleasing monster film The Host, which garnered four prizes, but this time two top honors went to arthouse/ festival titles. Still, it was very nice that local industry mainstay Sammo Hung got the Best Supporting Actor kudo for Ip Man 2.

As ever, there were special awards too: one to veteran Busan director Kim Dong-ho, one for Lifetime Achievement to Raymond Chow of Golden Harvest, one to Fortissimo Films for promotion of Asian cinema, and a prize to the top-grossing Asian film. That last was one of the three that went to Feng Xiaogang’s Aftershock (which we wrote about here). For a full listing go here. At Filmbiz Asia Patrick Frater suggests that the catastrophe in Japan gave the ceremony a sombre cast.

Milkyway on the move

Source: South China Morning Post.

When I arrived last week, I was greeted by a long story in the South China Morning Post announcing that Johnnie To Kei-fung and Wai Ka-fai (above), the movers behind Milkyway films, were embarking on a new production strategy.

Although Milkyway movies had cracked the mainland Chinese market in the past, notably with Breaking News (2004), To had made several films that could not be exported. His most personal films, crime stories like The Mission and PTU, violated the PRC’s demands that movies treat the police with respect. Worse, his Election films, which surveyed the treacherous power plays at work in Triad societies, was unthinkable as an export item–especially since the second entry extended its vision to the role played by PRC forces in controlling the Hong Kong crime scene.

Today, however, everyone acknowledges that the primary market for any Hong Kong film with a substantial budget is the mainland. In the SCMP story To and Wai announce their plans to craft a cycle of films for that audience. Romantic comedies and dramas have shown strong legs there, and true to their prolific energies, To and Wai have committed to making three romances this year. The first, Don’t Go Breaking My Heart, opened the festival on Sunday night. To is currently shooting the next one on the Mainland, and the third is set up to follow quickly.

Don’t Go Breaking My Heart, which is better than the Kiki Dee/ Elton John song, is an office romance like Milkyway’s 2000 hit , Needing You. . . . But the creators have deliberately updated the milieu, which includes not only a mainland émigrée as the heroine but also many scenes shot in China, as required by the financing.

The action starts just before the 2008 financial crisis. Cheng Zixin (a charming Gao Yuanyuan) is a lowly staffer at an investment company, while Cheung Sun-yin (Louis Koo) is an executive at a rival firm who first spies her from his sportscar. Noticing that Zixin occupies a cubicle by the window in a building adjacent to his, the ingratiating rascal begins flirting with her through pantomime. The third corner of the triangle is Fong Kai-wang (Daniel Wu), an architect turned alcoholic bum. The affair between Zixin and Sun-yin falls apart because of his attraction to other women, and she develops a platonic affection for Kai-wang, whom she urges to return to his profession. Three years later, as the financial sector is recovering, the three meet on more equal terms and Kai-wang and Sun-yin begin a serious competition for the young woman.

The financial crisis is no more than a pretext for the meet-cutes, handy coincidences, running gags, and emotional ups and downs characteristic of this genre. (One hopes that the recession gets more sober treatment in To’s long-gestating bank suspense drama, currently known as Life without Principle.) We get the common tension between the world of selfish business operations and that of nobler artistic expression, seen in Kai-wang’s love-inspired architectural designs. There’s also the convention, common to Asian romances, that these grown-up lovers are actually childlike, enjoying pets and stuffed animals. (You find it even in Chungking Express.) Don’t Go Breaking My Heart handles these conventions adroitly, but adds the To/ Wai flavor in its plot geometry and its strict but surprising ways with visual technique.

An American movie would have added subsidiary romances, usually involving the friends of the main characters. Instead, as in many Milkyway films, Wai’s plot is built out of rhyming situations. Sun-yin twice glimpses Zixin on a bus, both suitors use Post-Its and magic acts to attract her attention, characters’ zones of knowledge shift symmetrically, and an engagement ring pops up unexpectedly. Most remarkably, much of the courtship is carried on through skyscraper windows, as the men communicate with Zixin across adjacent buildings.

This last strategy allows To to build wordless sequences that rely on precise point-of-view cutting. At key moments, reverse-shot breakdown yields to striking compositions of the anamorphic frame. First we get two characters framed in different windows, but eventually, when Kai-wang tries to win Zixin away from Sun-yin, the love triangle finds diagrammatic expression in a spread-out three-shot.

Were shots like these accomplished through CGI? I wouldn’t put it past To to set up a location-based shot like this.

While subjecting its love story to a playful rigor that few Hollywood directors could summon up, Don’t Go Breaking My Heart never dissipates its inherent appeal to our emotions. Those emotions are all the stronger because Wai’s script shrewdly puts the outcome in doubt. The movie is a second-tier Milkyway product, I guess, and I could do with one less twist in its rather long running time. But it’s still a treat. It shows that in a popular cinema, creative minds can turn market demands to their own ends. And once the trio of romances is finished, the SCMP story hints, To and Wai may well turn to another crime saga, this time with the blessing of the PRC. We can only hope.

Wai Ka-fai, writer/ producer/ director of many Milkyway projects, is the subject of this year’s HKIFF Filmmaker in Focus cycle. Several of his older films, including the engaging parallel-worlds yarn Too Many Ways to Be No. 1, are in the program. There is, as usual, an informative book about Wai and To; a pdf sampler is here.

For much more on Milkyway on this site, go here. Ad insert: Films from the company, particularly those directed by To, are discussed in my new edition of Planet Hong Kong, available here.

PS 23 March: Thanks to Sean Axmaker for correcting my aging memory. The original entry attributed the song Don’t Go Breaking My Heart to the Captain and Tennille. Maybe I was subliminally wanting to see them again. No, wait, that can’t be it.

The target: Young mainland viewers of Avatar, China’s biggest box-office hit of 2010.