Overbooked

Thursday | March 10, 2011 open printable version

open printable version

Reading Habits, ©Joost Swarte 1990.

DB here:

Are blog readers book readers, let alone book buyers?

I sometimes wonder. There are only so many hours in a day, and the Net is, among other things, the Celestial Magazine Rack. Day or night you can find something funny, informative, or provocative. Thanks to sites like Arts and Letters Daily, Boing Boing, and their mates, you need never run short of reading material. And if you need a full-length read, there are always e-books. Who needs print?

So I thought when we took off for NYC for the month of February. My grand experiment: To bring along no printed book that I wouldn’t discard en route or in the city. I don’t have an e-book reader of any sort. Instead, I would read only what was loaded on my laptop, including Joseph Warren Beach’s Method of Henry James. If I purchased a codex for bedtime reading (there I read on my stomach or side, so a laptop wasn’t practicable), the unlucky item would be abandoned in our rental apartment for the next occupant. Dave would travel light.

The experiment succeeded only partly. I convinced myself that I had to lug along books I needed for the blog entry on eye-scanning. So my no-book mandate was limited to recreational reading. While I was in New York, though, a visit to the Strand put too many tempting items in reach. Most of those I ransacked and left behind, except for Stanislas Dehaene’s Reading in the Brain, far too stimulating to part with, and a mystery novel to be named later. But as our departure day approached, the itch returned and I ventured to Barnes & Noble for three of the new Harper editions of Agatha Christie classics (The ABC Murders, Five Little Pigs, and Crooked House, all sturdy items). These I toted back to Madison, reading the first two on the plane.

When I got home, finding several parcels awaiting my touch, I faced facts. I had deluded myself. I am both a book person and a Net person. I like text in both formats.

I love storing webpages and pdfs for searching, but books let me savage them with markups. Yes, I know you can annotate e-books, but it’s not the same. I think highlighting is ugly. I like to draw marginal asterisks, make solid lines under key points and wiggly lines under weak or silly ones, and add faces with frowns or rolled eyes. (Though I’m not as obsessive as this guy.) So in NYC my pencil traced tattoos over Dehaene’s information and arguments. In my whodunits I more discreetly inserted question marks, exclamation points, and curses as I reacted to the plots’ feints and jabs. Now I’m stuck. Once marked up, the books can’t be abandoned; some day I might need to consult them, or at least those pages I dog-eared and defaced.

Worse, as the Joost Swarte illustration up top shows, one book leads you to an epidemic of others. That realization dawned on me back in high school, when I learned that Coleridge would go on to read every book that was mentioned in the one he’d just finished. Hypertext isn’t new; reading done right is a combinatorial explosion.

Booked for murder

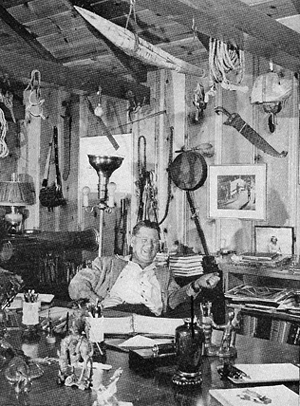

Erle Stanley Gardner.

So the Christies took me back to Robert Barnard’s A Talent to Deceive, a magnificent analysis of how Dame Agatha’s technical innovations changed the detective genre. (Creating a clue out of an apparent misprint—now that’s a tactic I can get behind.) Barnard’s book reminded me of another fine study in genre storytelling, Secrets of the World’s Best-Selling Writer by Francis L. and Roberta B. Fugate. I passed frrom The Method of Henry James to the method of Erle Stanley Gardner.

Now that we live in Harry Potter’s world, I suppose Gardner is no longer the sovereign of the best sellers. Does anyone still read Perry Mason or Doug Selby or Bertha Cool/ Donald Lam novels? But in his day, from the 1930s through the 1960s, Gardner was a central figure in US middlebrow literary culture. The Fugates’ book traces Gardner’s career, surveys the publishing scene he worked within, and compiles a great many notes on fiction techniques.

Now that we live in Harry Potter’s world, I suppose Gardner is no longer the sovereign of the best sellers. Does anyone still read Perry Mason or Doug Selby or Bertha Cool/ Donald Lam novels? But in his day, from the 1930s through the 1960s, Gardner was a central figure in US middlebrow literary culture. The Fugates’ book traces Gardner’s career, surveys the publishing scene he worked within, and compiles a great many notes on fiction techniques.

Gardner was probably the most fanatically productive and anally retentive of all mystery writers. In any month he could write a novel while turning out a hundred thousand words for the pulp magazines. He typed until his fingers bled, then he patched them with adhesive tape, and as he put it, “kept hammering.”

Typing was eventually replaced by dictation, putting Gardner in the same oral tradition as Edgar Wallace, Barbara Cartland, and Homer. By the time his first novel, the Perry Mason mystery The Case of the Velvet Claws (1933), was published he had already put his business on a rational basis. What he called his Fiction Factory employing up to seven full-time staff members. He composed all his stories himself, but his secretaries typed from his Dictaphone cylinders and kept track of characters, situations, and titles that he had used in published work, so that he could avoid repeating himself. (Shades of the bibles used for Star Wars and other sagas.) His success allowed him to buy a vast working ranch and build a compound where he and his staff could live together and maximize output.

Not that he withdrew completely from the world. The first Cool/Lam novel revealed that a California law could allow someone to get away with murder. After Gardner pointed out the loophole, the law was changed. Gardner also founded what he called the Court of Last Resort, a group of lawyers and criminologists who sought to overturn unjust convictions.

Along with pumping out fiction and crusading on legal matters, Gardner jotted copious notes to himself on story ideas, career goals, and general precepts of fiction writing. He tinkered with a “plot wheel” that would generate unexpected situations. The results do get you thinking: Locale: Wagon train. Character: Statesman. Predicament: Madness. . . Surely there’s a story there.

Dissatisfied with the wheels and gimmicks like Plot Genie and Plotto, Gardner decided to create his own machine for generating stories. The Fugates generously publish his outlines for “The Fluid or Unstatic Theory of Plots,” “Page of Actors and Victims,” “Character Components,” and so on. Some of these were synopses of discussions he would conduct with writers who were scripting the Perry Mason TV shows. They cut to the quick.

Every character in a story can and should have: 1. Point of strength; 2. Likeable or humorous weakness; 3. Prejudices; 4. Common characteristics. . . ; 5. Father, mother, other relatives dependent or wealthy; 6. Emotions—Love, hate, dislike, etc. for other characters; 7. Problems—And this is where you sell the character to the reader.

Gardner’s search for formulas led him to spell out, with unusual explicitness, the conventions of the form he worked with. (In this he intersects with those of us interested in poetics of media.) I would think that aspiring writers of fiction or movies could learn a lot from Gardner’s thoughts on craft.

If you’re interested in mystery plots, his ideas about the “murderer’s ladder” and “clue sequences” might provoke some ideas. He emphasized plotting a mystery from the criminal’s point of view, not from the investigator’s: It made for less contrivance. Consider as well Gardner’s notion of the “three-ring circus” plot. Take three conventional situations, he suggested, then hook them together in ingenious ways. The film example that occurred to me was the network narrative, which weaves several protagonists’ stories together. Pulp Fiction folds together a hitman story, a prizefighter story, a robbery story, and a few others to create something that felt fresh.

Gardner was a pack rat. The Fugates’ book could be very inclusive because his collection, donated to the Harry Ransom Center at the University of Texas, ran to over 36 million items. Among the memorabilia were Gardner’s notes on a book to which I often refer in lectures, J. Berg Esenwein and Arthur Leeds’ 1913 manual Writing the Photoplay. From Secrets I learned as well of two other books on popular plotting I needed to read, if not buy. I’m not saying what they are; you might beat me to them. Book information sometimes wants not to be free.

Crime on the set

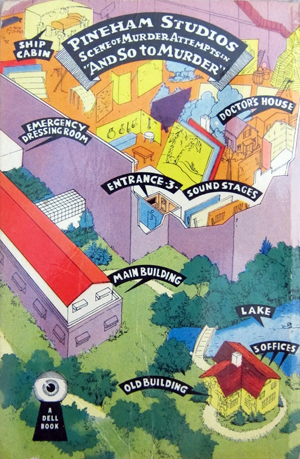

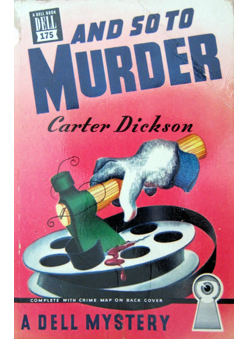

Why the old books? Why not Franzen’s Freedom? When it comes to fiction, more and more I’d rather read books I’ve read before instead of trying new things. Reader’s comfort food, I suppose; or at least the adolescent window. So at the Strand a 1947 mapback edition of Carter Dickson’s And So to Murder (1940) practically wriggled its way into my hand, like a cat begging to be stroked.

Carter Dickson was a pseudonym of the endlessly inventive John Dickson Carr, who throughout the 1930s and 1940s reliably turned out many detective novels and short stories. The Dickson ones feature Sir Henry Merrivale, a short, balding, profane doctor-barrister-baronet who is usually at the center of confusion. He once “sorta hit a cow with a train.”

The Old Man, as H.M. is known, enters And So to Murder rather late. The bulk of the action is occupied with a string of attempted killings during the preparation of a movie. It had been axiomatic in Golden Age detective stories that only homicide could justify a book-length tale, but here a tumble of conspiracies and Nazi espionage fill out the plot. There are as well the usual Carr chapter-endings, which unashamedly break off at points of high tension.

Experts rate And So to Murder not as highly as other Carr/ Dickson classics, although I find that several of my favorites, including gems like The Reader Is Warned (1939) and the short story “The House in Goblin Wood,” don’t score high numbers either. Of course all agree on the excellence of The Judas Window (1938), a virtuoso performance.

A cinephile can hardly resist the premise of my mapback. Monica Stanton, an unworldly provincial, writes a steamy novel called Desire. When it becomes a bestseller, Albion Films hires her as a screenwriter, but not in order to adapt her novel. Instead, she has to adapt And So to Murder, the novel by a handsome but deplorably bearded mystery writer, Bill Cartwright. Bill, of course, is assigned to adapt Desire. As flirtation and squabbling develop and a tough Hollywood screenwriter arrives to punch up the projects, Monica is threatened with poisoned cigarettes and sulfuric acid.

Carr novels like The Burning Court (1937) and The Crooked Hinge (1938, a masterpiece) carry a whiff of horror and brimstone, but the Dickson efforts are largely comedies. Like many Golden Age authors, Carr yoked his mystery to a developing romance, and his Dickson plots often treat the couple disrespectfully, showing how male vanity and female obstinacy create perpetual misunderstandings. His women, who typically wear no make-up, are smart and impertinent, and his men are clumsily chivalrous in their efforts to woo them.

And So to Murder is a good example of the sexual rivalry. Monica, barred from joining Bill at the War Office, decides to pay him back by plunging into the sordid side of London (short of visiting Soho) and picking up the first man she meets.

Bill Cartwright had done that deliberately, of course, to humiliate her. He had known all along that she would never be allowed into the War Office.

Her mind dwelt with hatred on the picture of Bill as he probably was now. He would be sitting in a spacious office, all mahogany and deep carpets, with bronze busts on bookcases, and an Adam fireplace. He would be drinking whiskey-and-soda—Monica herself, when she reached the Café Royal, was going to have absinthe—and listening to some thrilling anecdote of the Secret Service, told by a tall gray man with a deep voice, who sat at a desk with his back to the Adam fireplace.

Every film-goer knows that this is a true picture of the Military Intelligence Department, and Monica decorated it until pukka sahibs abounded.

It is, of course, a setting straight out of a 1930s film. Carr cleverly gives his heroine a fantasy suitable for her movie-struck imagination. Here’s one screenwriter who really believes the myths the studios spawn.

It is, of course, a setting straight out of a 1930s film. Carr cleverly gives his heroine a fantasy suitable for her movie-struck imagination. Here’s one screenwriter who really believes the myths the studios spawn.

The romance fulfills another purpose: it is a decoy. Carr fills out Bill’s and Monica’s embroglios with lively action, crisp descriptions, flashbacks, and fancies like the one just mentioned. Only later do you find that the smooth surface cunningly glides us toward quick reading, so that we’ll pass over hints that are ultimately of great importance. Carr was a connoisseur of magic, and although he could sometimes dwell on his clues, demanding that we puzzle them out, he was also skilled in the conjuror’s art of misdirection.

Carr’s affectionate mockery of stars, directors, producers, scenarists, and the down-at-heel British film industry holds up well. The plot centers on missing footage, and there are clues involving props and practical sets, along with a running gag about a coarse American mogul who keeps demanding big battle scenes filled with historical anachronisms.

There is no snobbery in this satire of moviemakers, only the zesty teasing that Carr aimed at aristocracy, pomposity, and pretension (especially when displayed by characters from the Continent). Although he was a deep-dyed Anglophile, Carr retained a vigorous American impatience with ceremony and circumlocution. At the same time, he could be serious about the gathering threat to his beloved Britain.

This was on Wednesday, the 23rd of August. Before a fortnight had elapsed there was a new noise in the earth. The dozenth pledge was broken; the gray mass burst loose; over London the sirens roared as the Prime Minister finished speaking; the great concrete hats of the Maginot Line revolved, and looked toward the West; Poland died, with all her guns still ablaze; the nights of the blackout came; and at Pineham, a small spot in England, a patient murderer struck again at Monica Stanton.

The passage ends with a typical Carr dodge (there will be no murder, so no murderer), but the lead-up has that rumble of thunder and kettledrums he could summon as occasion demanded. Still, the comic tone eventually wins out. The last line of the book is “It’s just one of the things that happen in the film business.”

The standard biography of Christie is Janet Morgan’s Agatha Christie. The recent Agatha Christie’s Secret Notebooks is not to my mind as illuminating as it might be. On Gardner, the unabashed puff piece by Alva Johnston, The Case of Erle Stanley Gardner, offers some insights. The only biography of Carr is Douglas Greene’s John Dickson Carr: The Man Who Explained Miracles. See also S. T. Joshi’s John Dickson Carr: A Critical Study. Old as it is, Howard Haycraft’s anthology, The Art of the Mystery Story, remains an excellent general source.

Thanks to Stef Franck and Gabrielle Claes for help with a Dutch translation.

To read the Readers’ Bill of Rights for Digital Books, go here. Image by Nina Paley, whom Kristin and Richard Leskovsky interviewed here.

PS 14 March: Jon Jermey kindly alerted me to the lively website he moderates on Golden Age Detective Fiction. It’s full of information and expert opinion, including Mike Grost’s overviews of John Dickson Carr’s works and Erle Stanley Gardner’s plotting tactics. Thanks to Jon for letting me know.