Bullets from the East

Sunday | March 20, 2011 open printable version

open printable version

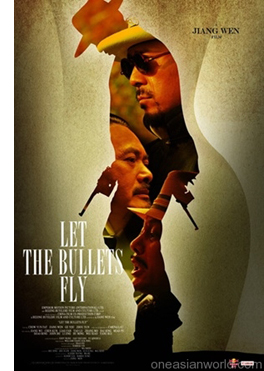

Chow Yun-fat, Jiang Wen, and Ge You in Let the Bullets Fly (2010).

DB here:

It’s mid-March, so it must be the first of a string of entries from the Hong Kong International Film Festival, a place I’ve visited regularly since 1995.

This year, the Boy Scout hotel was too full to take me, so I’ve wound up in the YMCA on Salisbury Road. If you want glimpses of the neighborhood, just watch Peter Greenaway’s Pillow Book. It’s as if he ventured only a few blocks from his hotel. (Unlikely to have been my Y; more likely he based himself at the far tonier Peninsula alongside.)

The Japanese quake, tsunami, and nuclear meltdowns are much on local people’s minds. Some people are worried that the light rains punctuating every day are carrying radiation, but so far there doesn’t seem any danger. I had planned to stop over in Tokyo on my way here, but after the quake struck I changed my flights. The good news is that the friends in Tokyo and Nagoya I’d planned to visit are safe.

Let the Bullets Fly, China’s biggest locally produced box-office hit to date was playing in a cycle of screenings devoted to major candidates for the Asian Film Awards, to be given Monday night. It was screened in the Grand cinema complex with Shaw Sound, which makes your seat vibrate in sync with the lower frequencies. This enhances any movie, I suppose. The Grand is located in Elements, a hypermall that has lost none of its weirdness. (The mazelike structure has four zones, Earth, Air, Fire, and Water.) I was pleased to note that the Grease Trap Room is still doing its duty.

Let the Bullets Fly, China’s biggest locally produced box-office hit to date was playing in a cycle of screenings devoted to major candidates for the Asian Film Awards, to be given Monday night. It was screened in the Grand cinema complex with Shaw Sound, which makes your seat vibrate in sync with the lower frequencies. This enhances any movie, I suppose. The Grand is located in Elements, a hypermall that has lost none of its weirdness. (The mazelike structure has four zones, Earth, Air, Fire, and Water.) I was pleased to note that the Grease Trap Room is still doing its duty.

Actor-turned-director Jiang Wen is one of the PRC’s most ambitious and intelligent directors. I’ve admired his In the Heat of the Sun (1994) and Devils on the Doorstep (2000, to be shown in its long version during the festival). Our blog files contain my impressions of his sumptuous, somewhat mystifying The Sun Also Rises (2007). But that film was a huge financial failure, and it’s generally agreed that he needed a hit. He provided it in Let the Bullets Fly.

This wild, cynical Eastern Western is set, the opening title tells us, in 1920 when warlords ruled great stretches of China. By choosing this pre-Communist era, Jiang is free to parade all manner of duplicity, amorality, and aggression, while still suggesting a modicum of revolutionary sensibility at the end. Pocky Zhang leads a band of marauders who capture a conman, Ma, and his wife. Ma’s swindle of choice is bribing officials to appoint him governor of a remote area and then squeezing taxes out of the locals before fleeing to his next target.

Captured, Ma pretends to be merely an advisor to the real governor, whom he claims was killed during the raid. Bandit Zhang decides to try his hand at governing and so brings his gang, along with Ma and his wife, to claim the post at Goose Town. There he butts heads with the local gang leader Huang Silang. The bulk of the plot presents an escalating series of comic and violent encounters between bandit-as-governor and warlord-as-godfather. Things come to a head when Huang offers Pocky Zhang a huge sum of silver to kill the biggest threat to his rule, none other than Pocky Zhang himself.

The beginning evokes Duck You Sucker, plunging us into Pocky’s raid on a steam train carriage (pulled by horses). As his gang races along with the carriage, we get the tone of lilting swagger that opened The Sun Also Rises. Very fast cutting, rushing tracking shots, and a bouncy musical score climax in Pocky’s adroit use of a flying axe to derail the carriage and send it flipping majestically into the river. Soon the bravado action gives way to games of deceit and disguise. Ma saves his skin by pretending to be his aide Tang. Pocky assumes the identity of the governor, while Huang has an identical double he will use as a decoy. Everybody suspects, rightly, that everybody else is lying. Even Pocky Zhang isn’t really pock-faced. (An alternate translation calls him Scarface Zhang. But he isn’t scarfaced either.)

The game is played out in fusillades of banter that are, my Chinese friends assure me, packed with gags and wordplay. Maybe it should be called Let the Bullshit Fly. Characters rattle out brief lines or single words in a thrumming rhythm that is underscored by frantic back-and-forth cutting: cinematic stichomythia. Overall, the film’s average shot length is about two seconds.

Let the Bullets Fly is a showcase for action scenes, dizzying dialogue, clever running gags (the bird-whistles that Zhang’s gang uses to communicate), and perhaps above all star performances. Three popular male actors dominate the proceedings, leaving poor Carina Lau as Ma’s wife little to do but look seductive and die early on. Ge You as Ma is querulous but cunning. Ma’s death, buried in a mountain of silver currency, balances exaggerated imagery and gory gags with a gentler humor as he tries to utter some last words. Chow Yun-fat hams it up agreeably in a dual role, as gangster Huang and his hapless, nattering double.

Central of course is Jiang himself as Pocky Zhang, a crack shot and an utterly confident, resourceful leader who spares a little time to eye the ladies. Director supremo Feng Xiaogang shows up in the prologue playing the unfortunate counselor Tang. His drowning in the train carriage carries a peculiar extra-filmic resonance: by the end of its run, Bullets broke the box-office record set by Feng’s Aftershock earlier in the year.

More generally, the film shows how filmmakers on the mainland are broadening and fine-tuning popular genres. Having mastered the costume epic, they have branched out, winning audiences with modernized comedies and relationship romances (e.g., Feng’s recent If You Are the One films). So why not Westerns too? After all, the genre has been transplanted to Italy, Germany, Spain, and even, some would say, Russia and India. Hong Kong’s Peace Hotel and South Korea’s The Good, the Bad, and the Weird showed that frontier conventions could be adapted for Asian audiences. Let the Bullets Fly seems to me not up to Jiang’s best work, and on one viewing, I found it occasionally monotonous and mechanical. Still, it should underwrite his more ambitious projects and encourage other directors to try their hands at a format that seems inexhaustible.

Thanks to Athena Tsui and Li Cheuk-to for sharing ideas over dim sum, and Shelly Kraicer for further clarification of names. For informative reviews of Bullets, see Ross Chen’s entry at lovehkfilm.com; James Marsh’s at twitchfilm; and Derek Elley’s commentary at Film Business Asia. This PRC review, in English, faults Jiang for his “unduly high opinion of himself.”

Speaking of Hong Kong: In case you didn’t know, the second, digital edition of my book Planet Hong Kong: Popular Cinema and the Art of Entertainment, is available here. Brace yourself for reports on my shameless efforts to hawk this item as the festival proceeds.

PS 21 March: Thanks to Luo Jin for a name and date correction.

A point of pilgrimage for every Hong Kong-addled cinephile: Chungking Mansions, on Nathan Road. You can see bamboo scaffolding on the left side.