Archive for March 2011

Bullets from the East

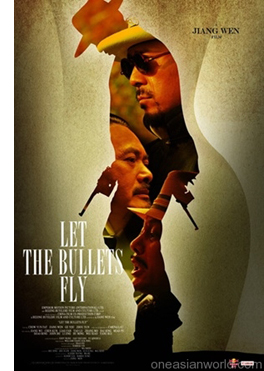

Chow Yun-fat, Jiang Wen, and Ge You in Let the Bullets Fly (2010).

DB here:

It’s mid-March, so it must be the first of a string of entries from the Hong Kong International Film Festival, a place I’ve visited regularly since 1995.

This year, the Boy Scout hotel was too full to take me, so I’ve wound up in the YMCA on Salisbury Road. If you want glimpses of the neighborhood, just watch Peter Greenaway’s Pillow Book. It’s as if he ventured only a few blocks from his hotel. (Unlikely to have been my Y; more likely he based himself at the far tonier Peninsula alongside.)

The Japanese quake, tsunami, and nuclear meltdowns are much on local people’s minds. Some people are worried that the light rains punctuating every day are carrying radiation, but so far there doesn’t seem any danger. I had planned to stop over in Tokyo on my way here, but after the quake struck I changed my flights. The good news is that the friends in Tokyo and Nagoya I’d planned to visit are safe.

Let the Bullets Fly, China’s biggest locally produced box-office hit to date was playing in a cycle of screenings devoted to major candidates for the Asian Film Awards, to be given Monday night. It was screened in the Grand cinema complex with Shaw Sound, which makes your seat vibrate in sync with the lower frequencies. This enhances any movie, I suppose. The Grand is located in Elements, a hypermall that has lost none of its weirdness. (The mazelike structure has four zones, Earth, Air, Fire, and Water.) I was pleased to note that the Grease Trap Room is still doing its duty.

Let the Bullets Fly, China’s biggest locally produced box-office hit to date was playing in a cycle of screenings devoted to major candidates for the Asian Film Awards, to be given Monday night. It was screened in the Grand cinema complex with Shaw Sound, which makes your seat vibrate in sync with the lower frequencies. This enhances any movie, I suppose. The Grand is located in Elements, a hypermall that has lost none of its weirdness. (The mazelike structure has four zones, Earth, Air, Fire, and Water.) I was pleased to note that the Grease Trap Room is still doing its duty.

Actor-turned-director Jiang Wen is one of the PRC’s most ambitious and intelligent directors. I’ve admired his In the Heat of the Sun (1994) and Devils on the Doorstep (2000, to be shown in its long version during the festival). Our blog files contain my impressions of his sumptuous, somewhat mystifying The Sun Also Rises (2007). But that film was a huge financial failure, and it’s generally agreed that he needed a hit. He provided it in Let the Bullets Fly.

This wild, cynical Eastern Western is set, the opening title tells us, in 1920 when warlords ruled great stretches of China. By choosing this pre-Communist era, Jiang is free to parade all manner of duplicity, amorality, and aggression, while still suggesting a modicum of revolutionary sensibility at the end. Pocky Zhang leads a band of marauders who capture a conman, Ma, and his wife. Ma’s swindle of choice is bribing officials to appoint him governor of a remote area and then squeezing taxes out of the locals before fleeing to his next target.

Captured, Ma pretends to be merely an advisor to the real governor, whom he claims was killed during the raid. Bandit Zhang decides to try his hand at governing and so brings his gang, along with Ma and his wife, to claim the post at Goose Town. There he butts heads with the local gang leader Huang Silang. The bulk of the plot presents an escalating series of comic and violent encounters between bandit-as-governor and warlord-as-godfather. Things come to a head when Huang offers Pocky Zhang a huge sum of silver to kill the biggest threat to his rule, none other than Pocky Zhang himself.

The beginning evokes Duck You Sucker, plunging us into Pocky’s raid on a steam train carriage (pulled by horses). As his gang races along with the carriage, we get the tone of lilting swagger that opened The Sun Also Rises. Very fast cutting, rushing tracking shots, and a bouncy musical score climax in Pocky’s adroit use of a flying axe to derail the carriage and send it flipping majestically into the river. Soon the bravado action gives way to games of deceit and disguise. Ma saves his skin by pretending to be his aide Tang. Pocky assumes the identity of the governor, while Huang has an identical double he will use as a decoy. Everybody suspects, rightly, that everybody else is lying. Even Pocky Zhang isn’t really pock-faced. (An alternate translation calls him Scarface Zhang. But he isn’t scarfaced either.)

The game is played out in fusillades of banter that are, my Chinese friends assure me, packed with gags and wordplay. Maybe it should be called Let the Bullshit Fly. Characters rattle out brief lines or single words in a thrumming rhythm that is underscored by frantic back-and-forth cutting: cinematic stichomythia. Overall, the film’s average shot length is about two seconds.

Let the Bullets Fly is a showcase for action scenes, dizzying dialogue, clever running gags (the bird-whistles that Zhang’s gang uses to communicate), and perhaps above all star performances. Three popular male actors dominate the proceedings, leaving poor Carina Lau as Ma’s wife little to do but look seductive and die early on. Ge You as Ma is querulous but cunning. Ma’s death, buried in a mountain of silver currency, balances exaggerated imagery and gory gags with a gentler humor as he tries to utter some last words. Chow Yun-fat hams it up agreeably in a dual role, as gangster Huang and his hapless, nattering double.

Central of course is Jiang himself as Pocky Zhang, a crack shot and an utterly confident, resourceful leader who spares a little time to eye the ladies. Director supremo Feng Xiaogang shows up in the prologue playing the unfortunate counselor Tang. His drowning in the train carriage carries a peculiar extra-filmic resonance: by the end of its run, Bullets broke the box-office record set by Feng’s Aftershock earlier in the year.

More generally, the film shows how filmmakers on the mainland are broadening and fine-tuning popular genres. Having mastered the costume epic, they have branched out, winning audiences with modernized comedies and relationship romances (e.g., Feng’s recent If You Are the One films). So why not Westerns too? After all, the genre has been transplanted to Italy, Germany, Spain, and even, some would say, Russia and India. Hong Kong’s Peace Hotel and South Korea’s The Good, the Bad, and the Weird showed that frontier conventions could be adapted for Asian audiences. Let the Bullets Fly seems to me not up to Jiang’s best work, and on one viewing, I found it occasionally monotonous and mechanical. Still, it should underwrite his more ambitious projects and encourage other directors to try their hands at a format that seems inexhaustible.

Thanks to Athena Tsui and Li Cheuk-to for sharing ideas over dim sum, and Shelly Kraicer for further clarification of names. For informative reviews of Bullets, see Ross Chen’s entry at lovehkfilm.com; James Marsh’s at twitchfilm; and Derek Elley’s commentary at Film Business Asia. This PRC review, in English, faults Jiang for his “unduly high opinion of himself.”

Speaking of Hong Kong: In case you didn’t know, the second, digital edition of my book Planet Hong Kong: Popular Cinema and the Art of Entertainment, is available here. Brace yourself for reports on my shameless efforts to hawk this item as the festival proceeds.

PS 21 March: Thanks to Luo Jin for a name and date correction.

A point of pilgrimage for every Hong Kong-addled cinephile: Chungking Mansions, on Nathan Road. You can see bamboo scaffolding on the left side.

Pleased to meet you. What’s the greatest movie ever made?

(From the Seth Saith blog)

Kristin here:

Way back in January Jim Emerson participated in the “Movie Tree House” conversation on Sergio Leone and the Infield Fly Rule. On January 14, his blog recounted his discussion of the differences between “average viewers” and those of us who are more intensely involved in films in one way or another:

I met a very nice, intelligent woman (maybe ten years older than me) at a New Year’s Eve party and she told me “The King’s Speech” was the best movie she’d ever seen. I responded politely by showing (genuine) enthusiasm for Geoffrey Rush’s performance. But I don’t know what to say to something like that. I mean, I had no reason or desire to dismiss her, but it wasn’t the kind of statement that calls for critical analysis, either. It was just social small talk. But I believe she was quite moved by the film. And, yes, there’s nothing at all wrong with that.

He added:

I thought of saying, “Wow. My favorite movie is ‘Nashville.’ Or maybe ‘Chinatown.’ Or ‘Only Angels Have Wings.'” But I didn’t think the conversation would have much opportunity to go anywhere from there, so I didn’t.

I suspect Jim’s experience is common among people whose main vocation is writing about films. When I meet someone who isn’t a film buff or scholar, he or she almost inevitably asks one of two questions: “What is your favorite film?” or “What do you think is the greatest film ever made?” From the looks on their faces, I suspect they really want to know the answer and think that it will be interesting, even gratifying. After all, meeting a film critic or historian is less common and more potentially interesting than meeting a mathematician.

Up to now, I have generally answered honestly that I think the greatest film ever made is Jacques Tati’s Play Time and that it’s probably my favorite as well. Or I say that it’s hard to choose, but some candidates would be  Ozu Yasujiro’s Late Spring, Jean Renoir’s The Rules of the Game, Sergei Eisenstein’s Ivan the Terrible, and Play Time. Almost invariably the smile on my interlocutor’s face fades into disappointment as he or she admits to never having heard of any of these films, let alone having seen them. Awkward pause, with conversation turning to other matters or my making a feeble attempt to say sometime to encourage the person to give these films a try.

Ozu Yasujiro’s Late Spring, Jean Renoir’s The Rules of the Game, Sergei Eisenstein’s Ivan the Terrible, and Play Time. Almost invariably the smile on my interlocutor’s face fades into disappointment as he or she admits to never having heard of any of these films, let alone having seen them. Awkward pause, with conversation turning to other matters or my making a feeble attempt to say sometime to encourage the person to give these films a try.

I think I’ve come up with a better way to answer these questions. I’ll say something like, “Well, lately I’ve really enjoyed True Grit and Toy Story 3.” This dodges the question, but the person is bound to have heard of these, likely to have seen one or both, and may well have something to say about them—though I hope it isn’t “Yes, that’s the best film I’ve ever seen.”

Maybe that tactic will work. After all, most movie-goers work on what in cognitive psychology is called “the recency effect.” Our memories of things we’ve just experienced are more vivid in our minds than those from longer ago, even though those older experiences may have seemed equally intense or pleasurable at the time.

I ran across a good example of this effect in an Amazon review of True Grit posted by Harold Greene. Giving the film five stars, he enthuses, “I am reluctant to declare it THE best movie I have ever seen in my life but in five weeks watching it every Saturday night I can recall none to surpass it.” As a fan of True Grit and the Coen Brothers, I would believe that possibly it is the best film Mr. Greene has ever seen. But it could equally be that the intense repetition of viewings may have solidified the recency effect and diminished his memory of other films that he esteemed equally at the time.

More generally, the recency effect tends to be borne out when one of my colleagues in film studies here at the University of Wisconsin-Madison surveys their students at the beginning of a course. The goal is to find out something about their knowledge of film going into the class. One question, “What is your favorite film?” almost invariably elicits a title released in the past year or so.

So I suspect that the party-goer asking about my favorite film would be satisfied with my talking about recent movies I’ve enjoyed. The real puzzle, though, is why such people would ask such questions to begin with.

One possibility is that most people have very little sense that there is a vast body of movies out there, from over a century and from many significant filmmaking countries. Their impression of film history, as reflected in the popular media, could reasonably be that the film I might name as the greatest is probably one they’ve heard of, maybe Casablanca or Citizen Kane or The Godfather or La Dolce Vita or even Avatar.

Could it be that my questioner is hoping, probably without realizing it, that I will name his or her own favorite film? Or at least a title that he or she has seen and enjoyed? Or at least heard of? In the latter case, the person can hold up his or her side of the conversation by responding, “Oh, I’ve heard of that and have been meaning to watch it. I must put it in my Netflix queue.” A satisfactory conclusion to that little stretch of social interaction, and it does happen, albeit rarely.

I try to imagine whether scholars of opera or poetry get such questions at parties. Does someone who has just been introduced to them ask what their favorite opera or poem is? Maybe. I wouldn’t. My typical response on learning that a perfect stranger standing in front of me is a professor of something is to ask what his or her area of specialization is, hoping that it’s something I know a bit about (Vivaldi operas as opposed to Verdi, nineteenth-century Victorian novels as opposed to Renaissance poetry).

to Verdi, nineteenth-century Victorian novels as opposed to Renaissance poetry).

I have to admit, some people I meet at parties do launch in by asking me what areas of film I study, which makes the subsequent conversation less likely to end in mutual embarrassment. That is, with me looking like a pointy-headed, ivory-tower intellectual who wouldn’t be caught dead watching Cedar Rapids (which I’m actually looking forward to seeing) and my new acquaintance looking like an ignorant clod who doesn’t look beyond this year’s Oscar nominees (even though he or she has probably in reality seen quite a lot of excellent movies).

This entry on Jim’s blog led to a touchy exchange in his comments section about whether he and the other participants in the dialogue were being condescending to “average viewers.” This sort of disagreement seems inevitable, since people who know a great deal about any subject are likely to seem condescending to people who don’t, even if that is not their intention. But the question I’m asking is not whether “average viewers” have good taste. Some do, some don’t. So far I’ve just been trying to figure out why many of them seem determined to ask experts questions that will very likely expose their own lack of knowledge.

Beyond that issue, though, is the symptomatic implication of these two nearly universal cocktail-party questions. I think people are more apt to ask “What do you think the greatest film is?” than “What do you think the greatest opera is?” because film is still taken less seriously as an art-form than are the “high” arts. Most people think they know more about film than they do about opera because almost anyone you and I are likely to meet goes to movies more than to operas. The fact that a steady diet of well-reviewed, even Oscar-nominated Hollywood films remains only a tiny slice of the entire range of surviving movies made so far doesn’t occur to them. The same is true even for those who see the occasional indie or foreign-language film.

It used to be that a good liberal-arts education gave a young person a solid foundation in fields like music and art. I took two four-credit semesters of classical-music appreciation as a freshman and have benefited ever since. I took literature courses, and although I took only one semester of art appreciation, I have filled in by visiting museums all over the world. Even so, I would be cautious in trying to make conversation about topics like ballet, which I realize I know very little about.

Yet, the “What’s your favorite film?” question doesn’t just come from neighbors I see only at the annual block-party potluck or over bed-and-breakfast buffets. It comes from college professors who themselves are often specialists in one of the arts. They probably would feel, as well-rounded intellectuals, required to know at least something about the other arts—except film.

David was once talking with a distinguished literary scholar who would have been appalled if someone in a university had never heard of Faulkner or Thomas Mann. But when David said he admired many Japanese films, the scholar asked incredulously, “All those Godzilla movies?”

That’s really the crux of what bothers me about the awkward great-film/favorite-film question. If it’s a non-academic who asks it, it tends to be a conversation-stopper, which is unfortunate. But anyone is entitled to love the movies they want to love and to believe, if they wish, that Avatar is the greatest film ever made.

But when academics who would claim to be well-educated in the arts look blank when I mention The Rules of the Game or one of the other likely masterpieces of world cinema, I do mentally pass judgment. Is it more important to be aware of Monteverdi’s Orfeo or Velasquez’s Las Meninas than of Renoir’s film? Obviously I would say no. Yet I don’t think that these academics feel particularly embarrassed at not recognizing the title of a mere film.

This is not to say that all liberal-arts academics in other fields are ignorant of film and its history. On the contrary, we have friends who certainly know as much about the subject as we do about any other art form. But on the whole, in-depth knowledge of film is fairly uncommon across the campus. There are physicists who play piano sonatas and biologists who love painting, but those typically aren’t the people showing up for our Cinematheque screenings. The question isn’t merely one of taste either. In universities, people in the other arts vote on funding for film programs. If they deep down consider film a lesser art form and hence an inconsequential subject of study, we can expect less support, or perhaps the sort of condescending support that says, in effect, “Well, I suppose that since it’s popular with students we should go ahead . . .”

A final note. If anything I have said here sounds “elitist,” you might consider the vast movement we see occurring in this country’s politics, especially on the far right, where any learning at all is equated with elitism and any experience in public office is equated with being tainted. When our educational system is being systematically downgraded, expecting people to learn things is simple common sense.

Rebooked

Will Success Spoil Rock Hunter? (Frank Tashlin, CinemaScope).

DB here:

Are blog readers book readers, let alone book buyers? I asked once before, but in a different tone of voice. Books are still being published, thick and fast, and everybody who cares about cinema should take a look at these.

In the frame

Ballet mécanique.

When the talk turns to the great film theorists of the heroic era, you hear a lot about Bazin and Eisenstein, less about Rudolf Arnheim. But the prodigiously learned Arnheim pioneered the study of art from the perspective of Gestalt psychology. Although he’s probably best known for his studies of painting in Art and Visual Perception, as a young man he was a film critic and in 1930 published a major theoretical book on cinema. First known in English as Film, then in its 1957 revision as Film as Art, this has long been considered a milestone. But Arnheim was famously skeptical of color and sound movies, and he had comparatively little to say about the many cinematic trends after 1930. (He died in 2007, aged 102.) While psychologists grew wary of Gestalt ideas, cinephiles embraced Bazin and academics moved toward semiotics and other large-scale theories. For some time Arnheim has seemed a graceful, erudite relic.

A new anthology seems likely to change that view. Arnheim for Film and Media Studies, edited by Scott Higgins, reveals one of the earliest and most energetic and pluralistic thinkers about modern media. The fourteen authors probe Arnheim’s ideas about film, of course–showing unexpected connections to the Frankfurt School and to avant-gardists like Maya Deren. But there are as well essays on Arnheim’s thinking on photography, television, and radio, along with studies that examine how his ideas would apply to comic books and digital media. Other contributors provide conceptual reconstructions, analyzing his ideas on composition and stylistic history.

A new anthology seems likely to change that view. Arnheim for Film and Media Studies, edited by Scott Higgins, reveals one of the earliest and most energetic and pluralistic thinkers about modern media. The fourteen authors probe Arnheim’s ideas about film, of course–showing unexpected connections to the Frankfurt School and to avant-gardists like Maya Deren. But there are as well essays on Arnheim’s thinking on photography, television, and radio, along with studies that examine how his ideas would apply to comic books and digital media. Other contributors provide conceptual reconstructions, analyzing his ideas on composition and stylistic history.

This is no esoteric exercise. The essays present probing arguments with patient lucidity. Encouragingly, most of the contributors are early in their careers. (I have a piece in the collection as well, an expanded version of a blog entry.) The anthology proves that a seminal thinker can always be reappraised. There’s always more to be understood.

In the Higgins collection Malcolm Turvey furnishes an essay on Arnheim’s relation to various strands of modernism. That vast movement is treated at greater length in Turvey’s new book, The Filming of Modern Life: European Avant-Garde Film of the 1920s. At the book’s core are close analyses of five exemplary films encapsulating various trends. Turvey studies Richter’s Rhythm 21 and abstract film, Léger and Murphy’s Ballet mécanique and cinéma pur, Clair’s Paris Qui Dort and Dada, Dalí and Buñuel’s Chien Andalou and Surrealism, and Vertov’s Man with a Movie Camera and the “city symphony” format. For each film Turvey provides informative historical background and, often, some controversial arguments. For example, he finds Léger to be surprisingly concerned with preserving classical standards of beauty. Indeed, one overall thrust of the book is to suggest that modernism was less a rejection of all that went before than a selective assimilation of valuable bits of tradition. (This applies as well to Eisenstein, I think, as I try to show in my book on his work.)

No less controversial is Turvey’s careful dissection of what has come to be known as “the modernity thesis.” This is the idea that urbanization, technological change, and other forces have fundamentally changed the way we perceive the world, perhaps even altered our basic sensory processes. Specifically, some argue, because the modern environment triggers a fragmentary, distracted experience, that experience is mimicked by certain types of film, or indeed by all films. Step by step Turvey argues that this is an implausible conclusion. This last chapter is sure to stir debate among the many scholars who argue for film’s essential tie to a modern mode of perception.

Harper Cosssar’s Letterboxed: The Evolution of Widescreen Cinema begins in the heyday of Arnheim and the silent avant-garde. Indeed, some of the early uses of widescreen, as in Gance’s Napoleon, are indebted to experimental film. But Cossar’s genealogy of widescreen also mentions horizontal masking in Griffith films like Broken Blossoms and lateral or stacked sets in Keaton comedies like The High Sign. More fundamentally, Cossar develops Charles Barr’s suggestion that the sort of viewing skills demanded by widescreen (at least in its most ambitious forms) were anticipated by directors who coaxed viewers to scan the 4:3 frame for a variety of information. The “widescreen aesthetic” was implicit in the old format, and technology eventually caught up to allow it full expression.

Harper Cosssar’s Letterboxed: The Evolution of Widescreen Cinema begins in the heyday of Arnheim and the silent avant-garde. Indeed, some of the early uses of widescreen, as in Gance’s Napoleon, are indebted to experimental film. But Cossar’s genealogy of widescreen also mentions horizontal masking in Griffith films like Broken Blossoms and lateral or stacked sets in Keaton comedies like The High Sign. More fundamentally, Cossar develops Charles Barr’s suggestion that the sort of viewing skills demanded by widescreen (at least in its most ambitious forms) were anticipated by directors who coaxed viewers to scan the 4:3 frame for a variety of information. The “widescreen aesthetic” was implicit in the old format, and technology eventually caught up to allow it full expression.

Cossar advances to more familiar ground, studying early widescreen practice in The Big Trail and moving to analyses of films by masters like Preminger, Ray, Sirk, and Tashlin. Although most chroniclers of the tradition stop in the early 1960s, Cossar presses on to consider the changes wrought by split-screen films like The Boston Strangler and The Thomas Crown Affair. The survey concludes with discussions of cropping techniques in digital animation (e.g., Pixar) and web videos, which often employ letterboxing as a compositional device. In all, Letterbox traces recurring technological problems and aesthetic solutions across a wide swath of film history.

Critics’ corner

Two of America’s senior film writers have revisited their earlier writings, with lively results. Dave Kehr’s collection When Movies Mattered samples his Chicago Reader period, from 1974 to 1986. Disguised as weekly reviews, Kehr’s pieces were nuanced essays on films both contemporary and classic.

Turn to any of them and you will find a relaxed intelligence and a deep familiarity with film history. By chance I open to his essay on Billy Wilder’s Fedora:

Turn to any of them and you will find a relaxed intelligence and a deep familiarity with film history. By chance I open to his essay on Billy Wilder’s Fedora:

It resurrects the flashback structure of his 1950 Sunset Boulevard, but it goes further, placing flashbacks with flashbacks and complicating the time scheme in a manner reminiscent of such demented 40s films noirs as Michael Curtiz’s Passage to Marseille and John Brahm’s The Locket. . . But the jumble of tenses also clarifies the film’s design as a subjective stream of consciousness. The images come floating up, appearing in the order of memory.

How many of those reviewers whose flash-fried opinions count for so much on Rotten Tomatoes can summon up information about the construction of Passage to Marseille or The Locket? And how many could make the case that Wilder, in returning to the forms fashionable in his early career, would repurpose them for the sake of a reflection on death, resulting in “a film as deeply flawed as it is deeply felt”? Kehr’s work from this period is appreciative criticism at its best, and he never lets his knowledge block his immediate response. “I admire Fedora, but it also frightens me.” It’s time we admitted that Dave Kehr, working far from both LA and Manhattan, was writing some of the most intellectually substantial film criticism we have ever had.

Also hailing from the Midwest is Joseph McBride, a professor, critic, and biographer. Apart from his rumination on Welles, his books have focused on popular, even populist, directors like Capra (The Catastrophe of Success), Ford (Searching for John Ford), and Spielberg (Steven Spielberg: A Biography). The University Press of Mississippi and bringing first two volumes of this trilogy back into print, and it has just reissued the third in an updated edition.

Here Spielberg emerges as far more than a purveyor of popcorn movies. McBride sees him as a restless, wide-ranging artist, and the additions to the original book have enhanced his case. McBride offers persuasive accounts of Amistad and A.I., which he regards as major achievements. He goes on to argue that Spielberg’s unique power in the industry allowed him to face up to central political issues of the 2000s.

He made a series of films in various genres reflecting and examining the traumatic effects of the September 11, 2001, attacks and the repression of civil liberties in the United States during the George W. Bush/ Dick Cheney regime. . . . No other major American artist confronted the key events of the first decade of the century with such sustained and ambitious treatment (450).

McBride is no cheerleader. He can be as severe on Spielberg’s conduct as on his films, criticizing much of the DreamWorks product as dross and suggesting that Spielberg sometimes trims his sails in interviews. I’d contend that McBride underrates some of Spielberg’s work, notably Catch Me If You Can and The War of the Worlds. But McBride has perfected his own brand of critical biography, blending personal information (he reads the films as autobiographical), tendencies within the film industry and the broader culture, and critical assessment. All studies of Spielberg’s work must start with McBride’s monumental book. Ten years from now we can look forward to another update; surely his subject will have made a few more movies by then.

Foreign accents

8 1/2.

Today we regard Citizen Kane as a classic, if not the classic. But for several years after its 1941 release it wasn’t considered that great. It missed a place on the Sight and Sound ten-best critics’ polls for 1952; not until 1962 did it earn a spot (though at the top). Its rise in esteem was due to changes in film culture and, some have speculated, the fact that Kane was a regular on TV during the 1960s. Something similar happened with His Girl Friday, another stealth classic. I’ve traced what I know about its entry into the canon in an earlier blog entry.

What about the postwar classics like Open City and Bicycle Thieves and the works of Bergman and Fellini and Antonioni and Kurosawa and the New Wave? Surely some of the films’ fame comes from their intrinsic quality—many are remarkable movies—but would we regard them the same way if their reputation hadn’t spread so widely abroad, especially in America? Questions like this lead us to what film scholars have come to call canon formation: the ways artworks come to wide notice, receive critical acclaim, and eventually become taken for granted as classics.

Consider this. The Toronto International Film Festival’s recent list of 100 essential films includes thirty non-Hollywood titles from the 1946-1973 period, more than from any comparable span. Of the TIFF top twenty-five, twelve are from that era. You can argue that these years, during which several generations of viewers overlapped, set in place a system of taste that persists to this day.

Consider this. The Toronto International Film Festival’s recent list of 100 essential films includes thirty non-Hollywood titles from the 1946-1973 period, more than from any comparable span. Of the TIFF top twenty-five, twelve are from that era. You can argue that these years, during which several generations of viewers overlapped, set in place a system of taste that persists to this day.

Tino Balio’s Foreign Film Renaissance on American Screens, 1946-1973 reveals a side of canon formation that’s too often overlooked. Balio is less concerned with analyzing films than Turvey, Cossar, Kehr, and McBride are. He is asking a business question: What led the U. S. film industry to accept and eventually embrace films so fundamentally different from the Hollywood product?

Several researchers have pointed to the roles played by influential critics, film festivals, and new periodicals like Film Comment and Film Culture. Intellectual and middlebrow magazines promoted the cosmopolitan appeal of the foreign imports. By 1963 Time could run a feverish cover story on “The Religion of Film” to coincide with the first New York Film Festival.

Balio duly notes the importance of such gatekeepers and agenda setters. But he goes back to the beginnings, with the small import market of the 1930s. Turning to the prime postwar phase, he broadens the cast of players to include the business people who risked buying, distributing, and publicizing movies that might seem hopelessly out of step with US audiences. He shows how small importers brought in Italian films at the end of the 1940s, and these attracted New York tastemakers, notably Times critic Bosley Crowther, who were keen on social realism. Within a few years ambitious entrepreneurs were marketing British comedies, Swedish psychodramas, Brigitte Bardot vehicles, and eventually the New Waves and Young Cinemas of the 1960s. As distributors fought censors and slipped films into East Side Manhattan venues, an audience came forward. The “foreign films”—often recut, sometimes dubbed, usually promoted for shock, sentiment, and sex—were positioned for the emerging tastes of young people in cities and college towns.

Balio offers fascinating case studies of how the films were handled well or badly. Kurosawa, he notes, had no consistent distributor in the US, and so his films gained comparatively little traction. By contrast there was what one chapter calls “Ingmar Bergman: The Brand.”

Balio offers fascinating case studies of how the films were handled well or badly. Kurosawa, he notes, had no consistent distributor in the US, and so his films gained comparatively little traction. By contrast there was what one chapter calls “Ingmar Bergman: The Brand.”

Bryant Haliday and Cy Harvey of Janus Films. . . devised a successful campaign to craft an image of Bergman as auteur and to carefully control the timing of each release. . . . Janus released the films in an orderly fashion to prevent a glut on the market and to milk every last dollar out of the box office. No other auteur received such treatment.

The work paid off: Bergman made the cover of Time in 1960, and soon The Virgin Spring and Through a Glass Darkly won back-to-back Oscars for Best Foreign Language Film. Eventually, Bergman and other foreign auteurs attracted the big studios. Now that small distributors had shown that there was money in coterie movies, the major companies (having problems of their own) embraced imported cinema—first through distribution and eventually through financing. If you admire Godard’s The Married Woman, Band of Outsiders, and Masculine Feminine you owe a debt to Columbia Pictures, which underwrote them.

Work like Balio’s does more than bring the name Cy Harvey into film history. It reminds us to follow the money. If we do, we’ll see that not every “foreign film” stands radically apart from big bad Hollywood. More generally, The Foreign Film Renaissance on American Screens reminds us that even high-art cinema is produced, packaged, and circulated in an economic system. The distinction between commercial films and personal films, business versus art, is a wobbly one. Rembrandt painted on commission and Mozart was hired to write The Magic Flute. Sometimes good art is good business.

I couldn’t work this in anywhere else: The bulk of the essays in Arnheim for Film and Media Studies are by people associated with our department at Wisconsin. They do us proud, naturally. Incidentally, Joe McBride went to school at UW too, and Tino and I taught together here for over thirty years.

Dave Kehr maintains a blog and teeming forum here.

Hart Perez has made a documentary, Behind the Curtain: Joseph McBride on Writing Film History. An excerpt is here. McBride’s website has information about his many projects.

James E. Cutting provides an unusually precise account of canon creation in his 2006 book Impressionism and Its Canon, available for free download here. I’ve written an earlier blog entry discussing Jim’s research into film.

My mention of American generations is based on Elwood Carlson’s study The Lucky Few: Between the Greatest Generation and the Baby Boom. Carlson examines the varying experiences and life chances of people who fought in World War II; people who came of age during the 1960s; and the less populated cohort that fell in between. Doing some pop sociology, I’d hypothesize that the art-film market’s growth relied on a convergence of all three, which were more disposed to art film than cohorts in earlier periods. For example, veterans who had served overseas and gone to college on the GI Bill were more familiar with non-US cultures than their parents and, I surmise, weren’t entirely put off by foreign films. When I first met Kristin’s mother, Jean Thompson, she already knew the work of Carl Dreyer, having seen Day of Wrath at an art cinema in Iowa City. She was in graduate school after World War II, on the G.I. Bill, as was her new husband, Roger, also in school on the G.I. Bill and managing that art cinema. They saw Children of Paradise and other wartime foreign films just getting their releases in the U.S., as well as post-war films like Bicycle Thieves.

The Lucky Few, also known as the Good Times generation, were born between the late twenties and the early 1940s. They were well placed to enjoy postwar prosperity and the period’s explosion of artistic expression. The Lucky Few cohort includes powerful film critics like John Simon (born 1925), Andrew Sarris (1928), Richard Roud (1929), Eugene Archer (1931), Susan Sontag and Richard Schickel (1933), and Molly Haskell (1939). Aged between twenty and thirty when the foreign-film wave struck, they were mighty susceptible to it. (Pauline Kael, though born in 1919, had a delayed career start, entering film journalism in the 1950s along with Sarris et al.) You might slip in David Thomson (born 1941), Jonathan Rosenbaum (1943), and Richard Corliss (1944).

The Baby Boomers jumped on the carousel in the 1960s, with results that are all too apparent. Dave Kehr and Joe McBride are Boomers, as are Kristin and I. Tino, for the record, is ageless.

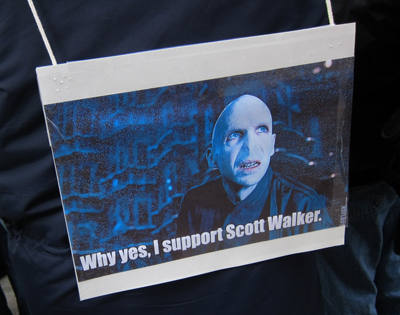

Minority Report.

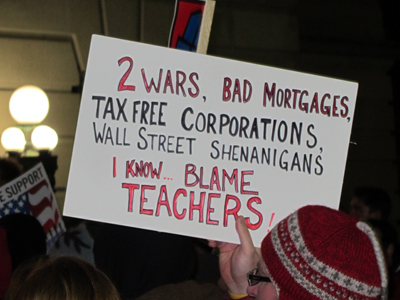

Spring: Forward

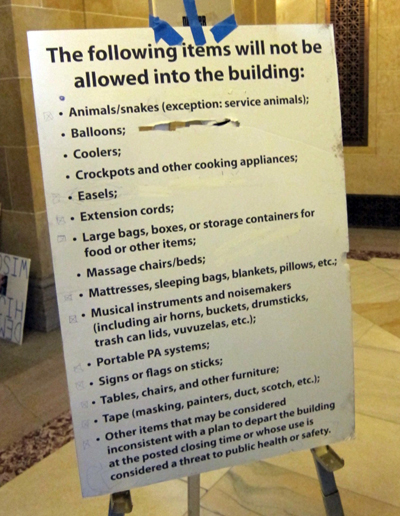

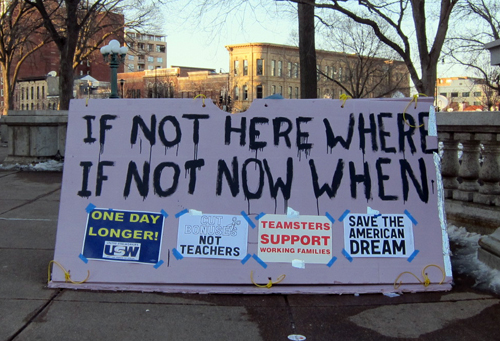

Ten days ago we returned to Madison and the political turmoil that we had watched from a distance. In just a few weeks, the Governor and the Republican majorities in the legislature thrust through a new budget and a bill drastically limiting the rights of state employees to bargain collectively. The actions, taken abruptly and perhaps in violation of Wisconsin law, triggered huge, peaceable protest demonstrations–the biggest yesterday, with perhaps as many as 100,000 people participating. A timeline of developments is here. A skeptical account of the Governor’s rationale is here. His telephone conversation with Not David Koch, which hasn’t lost any of its entertainment value, is here.

Wisconsin State Animal: The Badger.

Saturday 12 March: A tractor cavalcade around the square.

The rally continued throughout the afternoon.

Photo from Milwaukee Journal-Sentinel.

Go here for information about what may happen next.

Wisconsin State Motto: Forward.

Unless otherwise credited, photos by DB.

PS 13 March: See video coverage, including cow parade, here.