Archive for March 2011

Overbooked

Reading Habits, ©Joost Swarte 1990.

DB here:

Are blog readers book readers, let alone book buyers?

I sometimes wonder. There are only so many hours in a day, and the Net is, among other things, the Celestial Magazine Rack. Day or night you can find something funny, informative, or provocative. Thanks to sites like Arts and Letters Daily, Boing Boing, and their mates, you need never run short of reading material. And if you need a full-length read, there are always e-books. Who needs print?

So I thought when we took off for NYC for the month of February. My grand experiment: To bring along no printed book that I wouldn’t discard en route or in the city. I don’t have an e-book reader of any sort. Instead, I would read only what was loaded on my laptop, including Joseph Warren Beach’s Method of Henry James. If I purchased a codex for bedtime reading (there I read on my stomach or side, so a laptop wasn’t practicable), the unlucky item would be abandoned in our rental apartment for the next occupant. Dave would travel light.

The experiment succeeded only partly. I convinced myself that I had to lug along books I needed for the blog entry on eye-scanning. So my no-book mandate was limited to recreational reading. While I was in New York, though, a visit to the Strand put too many tempting items in reach. Most of those I ransacked and left behind, except for Stanislas Dehaene’s Reading in the Brain, far too stimulating to part with, and a mystery novel to be named later. But as our departure day approached, the itch returned and I ventured to Barnes & Noble for three of the new Harper editions of Agatha Christie classics (The ABC Murders, Five Little Pigs, and Crooked House, all sturdy items). These I toted back to Madison, reading the first two on the plane.

When I got home, finding several parcels awaiting my touch, I faced facts. I had deluded myself. I am both a book person and a Net person. I like text in both formats.

I love storing webpages and pdfs for searching, but books let me savage them with markups. Yes, I know you can annotate e-books, but it’s not the same. I think highlighting is ugly. I like to draw marginal asterisks, make solid lines under key points and wiggly lines under weak or silly ones, and add faces with frowns or rolled eyes. (Though I’m not as obsessive as this guy.) So in NYC my pencil traced tattoos over Dehaene’s information and arguments. In my whodunits I more discreetly inserted question marks, exclamation points, and curses as I reacted to the plots’ feints and jabs. Now I’m stuck. Once marked up, the books can’t be abandoned; some day I might need to consult them, or at least those pages I dog-eared and defaced.

Worse, as the Joost Swarte illustration up top shows, one book leads you to an epidemic of others. That realization dawned on me back in high school, when I learned that Coleridge would go on to read every book that was mentioned in the one he’d just finished. Hypertext isn’t new; reading done right is a combinatorial explosion.

Booked for murder

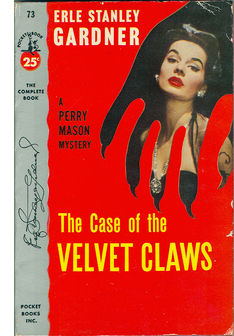

Erle Stanley Gardner.

So the Christies took me back to Robert Barnard’s A Talent to Deceive, a magnificent analysis of how Dame Agatha’s technical innovations changed the detective genre. (Creating a clue out of an apparent misprint—now that’s a tactic I can get behind.) Barnard’s book reminded me of another fine study in genre storytelling, Secrets of the World’s Best-Selling Writer by Francis L. and Roberta B. Fugate. I passed frrom The Method of Henry James to the method of Erle Stanley Gardner.

Now that we live in Harry Potter’s world, I suppose Gardner is no longer the sovereign of the best sellers. Does anyone still read Perry Mason or Doug Selby or Bertha Cool/ Donald Lam novels? But in his day, from the 1930s through the 1960s, Gardner was a central figure in US middlebrow literary culture. The Fugates’ book traces Gardner’s career, surveys the publishing scene he worked within, and compiles a great many notes on fiction techniques.

Now that we live in Harry Potter’s world, I suppose Gardner is no longer the sovereign of the best sellers. Does anyone still read Perry Mason or Doug Selby or Bertha Cool/ Donald Lam novels? But in his day, from the 1930s through the 1960s, Gardner was a central figure in US middlebrow literary culture. The Fugates’ book traces Gardner’s career, surveys the publishing scene he worked within, and compiles a great many notes on fiction techniques.

Gardner was probably the most fanatically productive and anally retentive of all mystery writers. In any month he could write a novel while turning out a hundred thousand words for the pulp magazines. He typed until his fingers bled, then he patched them with adhesive tape, and as he put it, “kept hammering.”

Typing was eventually replaced by dictation, putting Gardner in the same oral tradition as Edgar Wallace, Barbara Cartland, and Homer. By the time his first novel, the Perry Mason mystery The Case of the Velvet Claws (1933), was published he had already put his business on a rational basis. What he called his Fiction Factory employing up to seven full-time staff members. He composed all his stories himself, but his secretaries typed from his Dictaphone cylinders and kept track of characters, situations, and titles that he had used in published work, so that he could avoid repeating himself. (Shades of the bibles used for Star Wars and other sagas.) His success allowed him to buy a vast working ranch and build a compound where he and his staff could live together and maximize output.

Not that he withdrew completely from the world. The first Cool/Lam novel revealed that a California law could allow someone to get away with murder. After Gardner pointed out the loophole, the law was changed. Gardner also founded what he called the Court of Last Resort, a group of lawyers and criminologists who sought to overturn unjust convictions.

Along with pumping out fiction and crusading on legal matters, Gardner jotted copious notes to himself on story ideas, career goals, and general precepts of fiction writing. He tinkered with a “plot wheel” that would generate unexpected situations. The results do get you thinking: Locale: Wagon train. Character: Statesman. Predicament: Madness. . . Surely there’s a story there.

Dissatisfied with the wheels and gimmicks like Plot Genie and Plotto, Gardner decided to create his own machine for generating stories. The Fugates generously publish his outlines for “The Fluid or Unstatic Theory of Plots,” “Page of Actors and Victims,” “Character Components,” and so on. Some of these were synopses of discussions he would conduct with writers who were scripting the Perry Mason TV shows. They cut to the quick.

Every character in a story can and should have: 1. Point of strength; 2. Likeable or humorous weakness; 3. Prejudices; 4. Common characteristics. . . ; 5. Father, mother, other relatives dependent or wealthy; 6. Emotions—Love, hate, dislike, etc. for other characters; 7. Problems—And this is where you sell the character to the reader.

Gardner’s search for formulas led him to spell out, with unusual explicitness, the conventions of the form he worked with. (In this he intersects with those of us interested in poetics of media.) I would think that aspiring writers of fiction or movies could learn a lot from Gardner’s thoughts on craft.

If you’re interested in mystery plots, his ideas about the “murderer’s ladder” and “clue sequences” might provoke some ideas. He emphasized plotting a mystery from the criminal’s point of view, not from the investigator’s: It made for less contrivance. Consider as well Gardner’s notion of the “three-ring circus” plot. Take three conventional situations, he suggested, then hook them together in ingenious ways. The film example that occurred to me was the network narrative, which weaves several protagonists’ stories together. Pulp Fiction folds together a hitman story, a prizefighter story, a robbery story, and a few others to create something that felt fresh.

Gardner was a pack rat. The Fugates’ book could be very inclusive because his collection, donated to the Harry Ransom Center at the University of Texas, ran to over 36 million items. Among the memorabilia were Gardner’s notes on a book to which I often refer in lectures, J. Berg Esenwein and Arthur Leeds’ 1913 manual Writing the Photoplay. From Secrets I learned as well of two other books on popular plotting I needed to read, if not buy. I’m not saying what they are; you might beat me to them. Book information sometimes wants not to be free.

Crime on the set

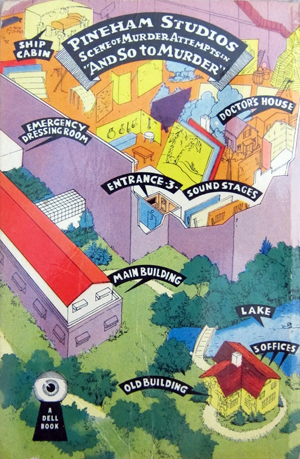

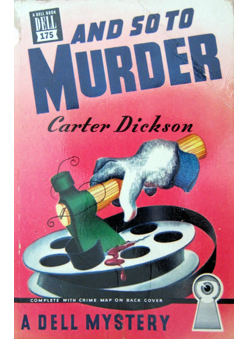

Why the old books? Why not Franzen’s Freedom? When it comes to fiction, more and more I’d rather read books I’ve read before instead of trying new things. Reader’s comfort food, I suppose; or at least the adolescent window. So at the Strand a 1947 mapback edition of Carter Dickson’s And So to Murder (1940) practically wriggled its way into my hand, like a cat begging to be stroked.

Carter Dickson was a pseudonym of the endlessly inventive John Dickson Carr, who throughout the 1930s and 1940s reliably turned out many detective novels and short stories. The Dickson ones feature Sir Henry Merrivale, a short, balding, profane doctor-barrister-baronet who is usually at the center of confusion. He once “sorta hit a cow with a train.”

The Old Man, as H.M. is known, enters And So to Murder rather late. The bulk of the action is occupied with a string of attempted killings during the preparation of a movie. It had been axiomatic in Golden Age detective stories that only homicide could justify a book-length tale, but here a tumble of conspiracies and Nazi espionage fill out the plot. There are as well the usual Carr chapter-endings, which unashamedly break off at points of high tension.

Experts rate And So to Murder not as highly as other Carr/ Dickson classics, although I find that several of my favorites, including gems like The Reader Is Warned (1939) and the short story “The House in Goblin Wood,” don’t score high numbers either. Of course all agree on the excellence of The Judas Window (1938), a virtuoso performance.

A cinephile can hardly resist the premise of my mapback. Monica Stanton, an unworldly provincial, writes a steamy novel called Desire. When it becomes a bestseller, Albion Films hires her as a screenwriter, but not in order to adapt her novel. Instead, she has to adapt And So to Murder, the novel by a handsome but deplorably bearded mystery writer, Bill Cartwright. Bill, of course, is assigned to adapt Desire. As flirtation and squabbling develop and a tough Hollywood screenwriter arrives to punch up the projects, Monica is threatened with poisoned cigarettes and sulfuric acid.

Carr novels like The Burning Court (1937) and The Crooked Hinge (1938, a masterpiece) carry a whiff of horror and brimstone, but the Dickson efforts are largely comedies. Like many Golden Age authors, Carr yoked his mystery to a developing romance, and his Dickson plots often treat the couple disrespectfully, showing how male vanity and female obstinacy create perpetual misunderstandings. His women, who typically wear no make-up, are smart and impertinent, and his men are clumsily chivalrous in their efforts to woo them.

And So to Murder is a good example of the sexual rivalry. Monica, barred from joining Bill at the War Office, decides to pay him back by plunging into the sordid side of London (short of visiting Soho) and picking up the first man she meets.

Bill Cartwright had done that deliberately, of course, to humiliate her. He had known all along that she would never be allowed into the War Office.

Her mind dwelt with hatred on the picture of Bill as he probably was now. He would be sitting in a spacious office, all mahogany and deep carpets, with bronze busts on bookcases, and an Adam fireplace. He would be drinking whiskey-and-soda—Monica herself, when she reached the Café Royal, was going to have absinthe—and listening to some thrilling anecdote of the Secret Service, told by a tall gray man with a deep voice, who sat at a desk with his back to the Adam fireplace.

Every film-goer knows that this is a true picture of the Military Intelligence Department, and Monica decorated it until pukka sahibs abounded.

It is, of course, a setting straight out of a 1930s film. Carr cleverly gives his heroine a fantasy suitable for her movie-struck imagination. Here’s one screenwriter who really believes the myths the studios spawn.

It is, of course, a setting straight out of a 1930s film. Carr cleverly gives his heroine a fantasy suitable for her movie-struck imagination. Here’s one screenwriter who really believes the myths the studios spawn.

The romance fulfills another purpose: it is a decoy. Carr fills out Bill’s and Monica’s embroglios with lively action, crisp descriptions, flashbacks, and fancies like the one just mentioned. Only later do you find that the smooth surface cunningly glides us toward quick reading, so that we’ll pass over hints that are ultimately of great importance. Carr was a connoisseur of magic, and although he could sometimes dwell on his clues, demanding that we puzzle them out, he was also skilled in the conjuror’s art of misdirection.

Carr’s affectionate mockery of stars, directors, producers, scenarists, and the down-at-heel British film industry holds up well. The plot centers on missing footage, and there are clues involving props and practical sets, along with a running gag about a coarse American mogul who keeps demanding big battle scenes filled with historical anachronisms.

There is no snobbery in this satire of moviemakers, only the zesty teasing that Carr aimed at aristocracy, pomposity, and pretension (especially when displayed by characters from the Continent). Although he was a deep-dyed Anglophile, Carr retained a vigorous American impatience with ceremony and circumlocution. At the same time, he could be serious about the gathering threat to his beloved Britain.

This was on Wednesday, the 23rd of August. Before a fortnight had elapsed there was a new noise in the earth. The dozenth pledge was broken; the gray mass burst loose; over London the sirens roared as the Prime Minister finished speaking; the great concrete hats of the Maginot Line revolved, and looked toward the West; Poland died, with all her guns still ablaze; the nights of the blackout came; and at Pineham, a small spot in England, a patient murderer struck again at Monica Stanton.

The passage ends with a typical Carr dodge (there will be no murder, so no murderer), but the lead-up has that rumble of thunder and kettledrums he could summon as occasion demanded. Still, the comic tone eventually wins out. The last line of the book is “It’s just one of the things that happen in the film business.”

The standard biography of Christie is Janet Morgan’s Agatha Christie. The recent Agatha Christie’s Secret Notebooks is not to my mind as illuminating as it might be. On Gardner, the unabashed puff piece by Alva Johnston, The Case of Erle Stanley Gardner, offers some insights. The only biography of Carr is Douglas Greene’s John Dickson Carr: The Man Who Explained Miracles. See also S. T. Joshi’s John Dickson Carr: A Critical Study. Old as it is, Howard Haycraft’s anthology, The Art of the Mystery Story, remains an excellent general source.

Thanks to Stef Franck and Gabrielle Claes for help with a Dutch translation.

To read the Readers’ Bill of Rights for Digital Books, go here. Image by Nina Paley, whom Kristin and Richard Leskovsky interviewed here.

PS 14 March: Jon Jermey kindly alerted me to the lively website he moderates on Golden Age Detective Fiction. It’s full of information and expert opinion, including Mike Grost’s overviews of John Dickson Carr’s works and Erle Stanley Gardner’s plotting tactics. Thanks to Jon for letting me know.

Venues and visions

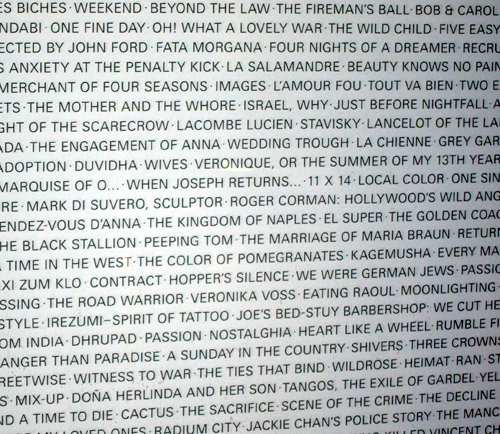

Vitrine outside future quarters of the Film Society of Lincoln Center (detail).

DB here:

During our month in NYC, we didn’t visit only art museums (although KT was at the Met a great deal). We also, no surprise, hit some of the city’s premiere movie spots. The places were often as impressive as the films, and all deserve the support of cinephiles both local and visiting. Herewith, a recap of our visits.

Fun things happen on your way through the Forum

Mike Maggiore, in the lobby of Film Forum.

Film Forum, running since 1970, has established itself as an outstanding venue for new releases and classics. It has done heroic work over the years. I stopped by to see my old Wisconsin friend Mike Maggiore, one of FF’s programmers, and met his colleagues, including Karen Cooper, a legend in US film culture. They had just recently had a remarkable triple-night string of visitors: Scorsese introducing his new documentary Public Speaking, Jerry Schatzberg with Scarecrow, and Paul Schrader with a fresh print of Diary of a Country Priest. The current FF program, running on three screens, is here and it’s very rich.

Uncle Boonmee will have hit FF by the time you read this. Chris Ware’s gorgeous poster decorates the Forum lobby.

The gem of Astoria

Under MoMI projection, Rachael Rakes (Assistant Film Curator), David Schwartz (Chief Curator), KT, Ethan de Seife (Professor, Hofstra).

The refurbished Museum of the Moving Image in Astoria is a thing of great beauty. Family-friendly, with lots of hands-on kid activities, it also offers a bounty to the cinephile.

For one thing, it has a superb screening theatre. We sampled it when MoMI screened a pretty print of King Hu’s The Valiant Ones (1975). Kristin and I were happy to see our old favorite again.

The same hall gave us a restoration of Manoel de Oliveira’s Doomed Love (1978). The movie, 4 ½ hours long, was shot in 16mm for television. It frankly acknowledges its novelistic source by including stretches of letters and florid declamation (“I will be dead to all men, except you, Father!”), as well as a plot turning on forbidden love and oppressive social relations. This is a world of parlors, convents, trusty servants, candlelit rooms, barred windows, and lovers who actually waste away. The title could apply to virtually every character, down to the maidservant who adores our protagonist and vows, “When I see I am not needed, I will end my life.” The affair draws others into its downward spiral, leaving the hero plenty of time to reflect on his misery and the pain he has inflicted on others.

The plot is quite engrossing in the manner of a triple-decker novel. That makes it all the more surprising that we get no Viscontian spectacle or even the plush upholstery of a Masterpiece Theatre episode. The presentation is rather dry and detached. I wondered if Ruiz’s recent Mysteries of Lisbon, drawn from another novel by Camilo Castelo Branco, was in effect a reply to Oliveira’s film. By comparison with Ruiz’s sparkling compositions and glissando flashbacks, Doomed Love looks reticent and austere.

The austerity is heightened by a self-conscious stylization. The music is aggressively modern, and the lengthy takes (the average shot runs about a minute) are often shot with the low, straight-on camera reminiscent of early cinema.The film begins with a partial view of a door opening, inviting us into the story world, but obliquely. The film closes with a hand lifting a bundle of love letters from the sea and a voice-over (Oliveira’s) explaining how the novel came to be written. The images provide as overt a marking of a narrative’s beginning and its end as you could ask for, and one completely in keeping with the film’s balance between respect for artifice and its concern to let compromised passions leak through.

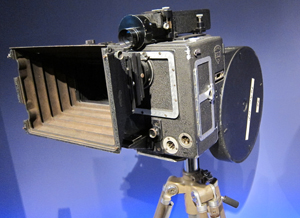

MoMI also hosts a splendid exhibition of media technology. One floor is a wonderland of cameras, sound rigs, printers, and projectors of all sorts, from film to TV and beyond. One favorite among many: A Mitchell VistaVision camera from 1954. It’s a funny-looking thing, but it took very crisp pictures. The horizontal film transport allowed larger and sharper images than the vertically-run formats that were normal for 35mm.

There are also displays devoted to screenplays, make-up, hairdressing, and special effects. I was especially taken with the finely detailed miniature for the Tyrell corporation building in Blade Runner.

In all, MoMI deserves all the praise it has gotten after its reopening. Rochelle Slovin, the founding director of the museum, started in 1981 and is retiring this week. She can be proud of what she and her colleagues have accomplished.

Jaywalking down Broadway

Wundkanal (Thomas Harlan, 1984).

Then there’s Lincoln Center, another long-time shrine of cinephilia. Like MoMI, the Film Society is in the process of building. The new complex will house theatres, a café, and a flexible lobby space. It’s scheduled to open in late spring.

The Film Society’s František Vlácil retrospective early in our stay brought this little-known filmmaker to my attention. I had seen only his best-known item, Marketa Lazarova (1967), and that quite a while back. So I was happy to catch his charming early short, Glass Skies (1958), and three features.

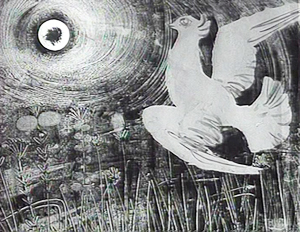

Vlácil mastered both filmic poetry and prose. The White Dove (1960) is a simple, lyrical story of two young people who never meet: a girl living in a beachside town and a wheelchair-bound boy in the city. Alternating sequences show them brought together by the homing pigeon that the girl sends out. The boy in a moment of thoughtless cruelty shoots the pigeon with his air rifle. Soon, with the help of an artist living in the same apartment house, he nurses the bird back to health. The film is richly shot in crisp, wide-angle black-and-white, and Vlácil exploits eyeballish imagery to create links between the girl’s seaside milieu and the artist’s Chagall-like paintings.

Like most filmmakers moving from the 1960s to the 1970s and from black and white to color, Vlácil recalibrated his visual design. Smoke in the Potato Fields (1976) gets your attention from the start with its disconcerting cutting during an airport departure. Laconic and elliptical, shot with long lenses and long takes, it tells an understated story of a middle-aged doctor moving to a small-town clinic. We get a cross-section of the townsfolk, from ambulance driver and gravedigger to censorious nurse and an unhappy married couple. The central drama concerns the doctor’s care for a tomboyish girl who gets pregnant and considers an abortion.

Shadows of a Hot Summer (1977), set in 1947 and shortly before the Communist takeover of the Ukraine, is more conventionally gripping. A farm family is held prisoner by rapacious resistance fighters. The taciturn father has no allies among the locals, who seem to resent his prosperity, and he dares not call attention to his plight. As in a Boetticher film, the hero plays his hand judiciously, mostly passive but carefully picking the battles he can win. The final sequence, precipitated when the marauders find him hoarding shotgun shells, is a taut, suspenseful exercise in action cinema. Shadows of a Hot Summer has daring stretches of silence and an unsettling score, along with discreet zoom shots typical of the period worldwide. These installments in the Vlácil retrospective show that we nonspecialists still probably underestimate the range of artistry that could be achieved in the apparently inhospitable atmosphere of Communist Eastern Europe.

Film Comment Selects brought us a host of strong items, of which I caught four. I had missed Jia Zhangke’s I Wish I Knew (2010) at Vancouver, so I was happy to catch up with it. It seems to me a moving but minor effort in his career, lacking the bolder organization of the comparable Useless (2007; the latter in our blog here) and 24 City (2008). I didn’t think that the figure of the wandering woman Zhao Tao, punctuating people’s recollections of life in Shanghai, developed very much. Still, I was struck by how much Jia’s interviewees were able to say about the effects of the Cultural Revolution on their lives, and there is an unforgettable account by a woman of her father’s execution at the hands of the KMT.

Film Comment Selects brought us a host of strong items, of which I caught four. I had missed Jia Zhangke’s I Wish I Knew (2010) at Vancouver, so I was happy to catch up with it. It seems to me a moving but minor effort in his career, lacking the bolder organization of the comparable Useless (2007; the latter in our blog here) and 24 City (2008). I didn’t think that the figure of the wandering woman Zhao Tao, punctuating people’s recollections of life in Shanghai, developed very much. Still, I was struck by how much Jia’s interviewees were able to say about the effects of the Cultural Revolution on their lives, and there is an unforgettable account by a woman of her father’s execution at the hands of the KMT.

I’m a big fan (at a distance) of the Chauvet caves and their Ice Age imagery, so Herzog’s Cave of Forgotten Dreams (2010), a 3D tour of the site, was right up my alley. The film turned out to be a strong argument for 3D (as Kristin anticipated), since it lacked that sense of cardboard-cutout planes you usually get and really brought out volumes. The tigers, bison, and other wondrous creatures seemed to bulge and ripple across the walls.

The biggest revelation the Film Comment program held for me was the double bill of Thomas Harlan’s Wundkanal (Gunwound, 1984) and Robert Kramer’s Notre Nazii (Our Nazi, 1984). Wundkanal was made by Thomas Harlan as part of his crusade to expose the bad faith of postwar Germany, where many former Nazis held positions of power. Harlan’s father was the Nazi filmmaker Veit Harlan, and as Kent Jones pointed out in his illuminating introduction, the son seems to have taken upon himself the burden of guilt that his father should have felt.

Wundkanal proposes that a terrorist gang has kidnapped the respectable citizen Dr. Seibert, interrogated him about his murderous past, recorded the sessions on videotape, and eventually staged some of their own suicides as part of the exercise. Dr. S. is played by Alfred Filbert–himself a Nazi let out of prison for medical reasons. The whole production, then, becomes both a vision of Germany’s blindness to history and a trap for a man whom Thomas Harlan suggests has gotten off far too easily. “A new idea: to use the real criminal, to deceive him and convince him it was a film about him.”

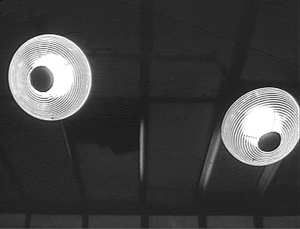

Filmed by the great Henri Alekan, it is a phantasmagoria. We are in a sunless bunker jammed with old photos, thermos jugs, automatic pistols, video clips from a Harlan film, and other detritus: a sort of chamber-play version of a Syberberg no-man’s land. Questioned by offscreen interrogators, Dr. S. admits to his crimes plaintively. The hallucinatory quality of the exercise is enhanced by sound cuts that split a sentence into bits (sometimes clear and close, sometimes filtered through speakers) and a drifting camera that may start on Dr. S. but then wanders across the litter to end on a video image of Dr. S. testifying in another session, at which point the sound of that session may take over. In one passage, the camera tours the room and picks up several bits of Dr. S.’s testimony, in the real space and in several video monitors crowding the area.

Kramer’s Our Nazi is in a way a making-of for Wundkanal, but it’s also a powerful film in its own right. Acting as his own cameraman for the first time, Kramer (director of the classic militant films The Edge, Ice, and Milestones) takes us behind the scenes to show Thomas Harlan’s obsessions and to expose Filbert more directly than Wundkanal does. Harlan talks of the fatal love he had for his father, reflecting that the old man’s charm finally withered in the face of his inhuman complicity with the Reich. Intercut with this soliloquy are shots of Filbert being made up for his video scenes, as he talks of his dueling scars and his youth: “All the ambitious men became Nazis.”

Our Nazi gives us two disturbing confrontations, one with Kramer sitting Filbert down and charging him with crimes against humanity, the other more prolonged and painful. Harlan and the crew encircle their star and hurl accusations at him. This scene, glimpsed and abstracted in Wundkanal, pulls the viewer in different directions as the feeble old man tries to escape Harlan’s relentless recitation of Filbert’s war crimes. In the discussion with Kent Jones after the screenings, Paul McIsaac rightly called the Kramer film a demonstration of the concreteness that direct cinema can yield. Shot in Hi-8, Our Nazi counterbalances the abstract, somewhat detached artifice on display in Wundkanal. Kramer dwells on unexpected details, such as Alekan hesitating to autograph a souvenir production photo for old Filbert. The two movies need to be seen together because they engage in a crosstalk that yields provocatively different information, emotions, and cinematic resources.

Our month in New York went by all too fast. We seldom visit the city these days; I’m in Hong Kong more often than Manhattan. Our trip brought back memories of my undergrad visits from Albany in the 1960s (packing four films into a day-trip) and, during the 1970s, doing dissertation research and visiting friends and teaching for a semester at NYU. It also allowed me to get back in touch with some of my oldest friends, like Rich Acceta-Evans from junior-high days. And the trip reminded me of what a cosmopolitan film culture is like, with institutions like these and still others (Anthology Film Archives, MoMA, etc.) braving tough times to bring the right movies to lucky audiences.

Apart from those named above, I want to thank the friends we met with during our stay. Scott Foundas was particularly helpful on this entry. I gave talks at various venues, so I’m grateful to Malcolm Turvey of Sarah Lawrence College, to the NYU Film Studies faculty, and to Patrick Hogan at the University of Connecticut–Storrs. Special thanks to Ken Smith and Joanna Lee for arranging a visit to the Museum of Chinese in America for a discussion of Planet Hong Kong.

Speaking of Planet Hong Kong, I discuss The Valiant Ones in Chapter 8 there, as well as in the essay “Richness through Imperfection: King Hu and the Glimpse,” in Poetics of Cinema. For a sensitive examination of Doomed Love, go to Tativille.

Some films in the Film Society’s Vlácil retrospective are available on DVD from Facets Multimedia. Wundkanal and Our Nazi have been issued on a single DVD edition with English subtitles, and it can be found on the Edition Filmmuseum site. Every film studies and filmmaking department should order it, I believe. See also “Truth or Consequences,” Kent Jones’ essay in Film Comment 46, 2 (May/ June 2010), 48-53, from which I’ve taken the Harlan quotation. Jones discusses other films, including Christoph Hübner’s 2007 study of Thomas Harlan, Wandersplitter, which is also available on a Filmmuseum disc. Thomas Harlan is one of the main interviewees in the documentary Kristin recently wrote about, Harlan: Im Schatten von Jud Süss.

For more coverage of the “Film Comment Selects” series, see R. Emmett Sweeney’s review on the Movie Morlocks site, with particularly discerning remarks on I Wish I Knew. Jesse Cataldo provides sharp commentary on Wundkanal at The House Next Door.

Alfred Filbert, confronted with the tattooed arm of an Auschwitz survivor (Our Nazi).