Molly wanted more

Wednesday | April 27, 2011 open printable version

open printable version

The Crime of M. Lange.

DB here:

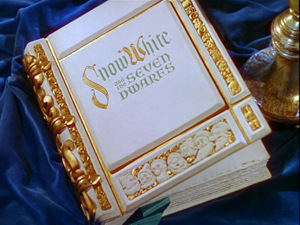

I was watching Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs some years ago with a friend’s three-year-old daughter. Molly hadn’t seen the movie before, and she watched it in a fascinated silence. At the end, Snow White and the prince leave the dwarfs and ride off into the distance.

At this point Molly cried, “More!”

This surprised me. How could she know, on her first pass, that the story was ending?

In and out

It has no name that I’m aware of, but it’s one of the most common conventions of movie storytelling. At the end of the film, the story world closes itself off from us. The characters turn away, perhaps walking into the distance. We may get a distant long shot of the scene. In some cases the camera accentuates this withdrawal by craning or tracking away from the action.

At the end of The Wild One, the biker hero smiles at the woman he’s met and goes out into the street. After exchanging a glance with the ineffectual sheriff, he swings his motorcycle around, his back to us. Cut to an extreme long shot as he rides off.

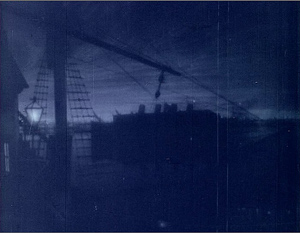

Once you notice this sort of ending, you’re likely to think about beginnings. Sure enough, we find some symmetry. A movie often visually brings us into the story world. Most common is an inward progression, moving from a large view to the central space of action. As far back as 1919, Griffith started Broken Blossoms with an overall view of the harbor and an explanatory title.

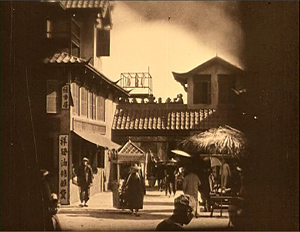

Then we have a gradual entry into the Chinese neighborhood, moving steadily from long shots to closer views. The young ladies we encounter aren’t major characters in the plot, but we’re still slowly drawn into the story world.

At the film’s end, Griffith’s cutting will manage a parallel withdrawal, from the lovers to the temple and back to the waterfront view.

In fact, Snow White starts with a comparable, if somewhat smoother shift inward, from the exterior of the Queen’s castle then, via camera movement and dissolves, to the Queen at her mirror.

This last shot reminds us that alternatively, a film can start with the characters coming forward, as if to meet us. This is the way The Wild One begins.

Any sort of combination is possible. The Silence of the Lambs starts with Clarice Starling climbing up a hill toward us and pausing long enough for us to register her as a protagonist.

She then turns and runs off into the forest. If this were an ending, we might see her go off further and further into the distance. But this is an opening, so we follow her with a tracking shot forward, letting her lead us into the story action. Soon we’re back to the frontality and intimacy of an opening passage, like the shot of the Queen.

At the end, Jonathan Demme gives us a pair of “farewell” shots. The first occurs when Clarice, who’s been talking to Dr. Lecter on the phone, hears the line go dead. We pull away from her.

The second farewell shot takes place on Lecter’s end in a Caribbean island. It shows him rising to follow Chilson and walking away from us, to be swallowed up into the crowd.

The Silence of the Lambs takes leave of its protagonists in two alternative ways: If the camera doesn’t move away from our characters, it seems, then the characters move away from the camera. They may even seal themselves off, as when a flight attendant pinches shut the curtain at the end of The Hunt for Red October.

So when we speak of films’ “openings” or “closings,” it seems that we are often talking about a world that initially invites us in but will finally expell us, however slowly and politely.

See it here!

Researchers play Jeopardy! Their answers always take the form of a question. Most film critics work in the declarative mode (“The performances are gripping”), but ideally the academic film researcher works in the interrogative mode. What is this pattern of beginnings and endings doing in movies? How does it work? How did it become common? And how do we learn it?

Take the first question, about the purposes and functions of the device. At one level its neat symmetry mimics the sort of frame that we find in other sorts of narrative, particularly oral storytelling. Fictional stories need to be set off from the surrounding flow of discourse. When we hear “Once upon a time,” we all know a fairy tale is starting. There are equivalents in other oral traditions, as in “Here is a tale . . . .” (Yoruba) and “See it here!” (Hause).

Likewise, oral storytelling traditions use formulaic final lines. In our fairy tales, it’s often “And they lived happily ever after.” Native American folk tales may finish with the storyteller simply saying, “The end” or “Tied up.” African oral epics sometimes use the formula “That is what I know” or “Let us leave the words right here.”

In fact, I cheated a little with my examples from Snow White. The film actually is bracketed by a literal opening and closing.

In film, however, the symmetrical structure is only part of the answer. While a film can copy the literary idea of opening and closing a written text, the medium as a whole offers something more. Thanks to the visual nature of movies, the widening or closing-off of the story world can mimic the act of our entering or backing out of a tangible situation. That’s what we see in Snow White and my other examples. In a sense we greet the characters, and after spending some time with them we bid them farewell. The sense of entering and leaving their world is harder to capture so concretely in literature or theatre.

So we need a more specific account of the convention. Surely you’ve thought about the most obvious candidate. The entry/ leave-taking pattern mimics our activities as perceiving, socially inclined people. For creatures like us, to encounter a new situation or setting simply involves approaching it or letting it approach us, then becoming part of it and fixing our attention on its details. At a party, we amble closer to a knot of people we want to talk with, or someone comes up to us. Sooner or later that encounter ends or trails off, and we withdraw or turn away or watch when others depart. More poignantly, the extreme long-shot option can recall moments when a car or bus or train carried us away from our loved ones. In any case, thanks to moving images the salient features of this very common experience can be made tangible for viewers.

This convention, we might say, is just natural. Molly, who had already logged three years of social experience, could plausibly make the analogy with ease. She recognized that her encounter with the world of Snow White was coming to an end–the characters were leaving her–and could express her regret.

This common-sense answer is, I think, basically right. But it needs to be fortified against some objections.

For one thing, not all films use this convention. Lots of films start with close-ups of particular items in an environment, plunging us into details without a gradual entry (below, Back to the Future; Muriel; ou le temps d’un retour).

And lots of films don’t end with marks of withdrawal or closure. They end on close views, often of the characters or a significant object (below, Le Silence de la mer; Sorry, Wrong Number).

If this pattern were biased by our natural proclivities, wouldn’t it be more common than it is? And if it comes so naturally, why wasn’t it present at the start of cinema, as soon as people started telling stories? Most of the storytelling techniques we now consider very user-friendly, like cutting and camera movement, emerged after many years of moviemaking. It’s akin to a problem in the history of painting: Why did painters need centuries to learn to imitate the way things look?

Moreover, the naturalness can look pretty unnatural. Nobody lies down in the middle of the road to let a horde of bikers sweep by, as in the beginning of The Wild One. The high angle at the end of the movie doesn’t imitate anybody’s likely point of view; it mimics, if anything, a godlike perspective we almost never get. Similarly, the cuts and dissolves that link the views in Broken Blossoms and Snow White don’t have any parallel in our real experience. Tied to our bodies, we can only move toward or away from situations in real time, step by step. The time-compression and freedom of position we get on film are far from natural. In sum, the concrete ways in which this immersion/ withdrawal pattern shows up in actual movies suggest that the films aren’t imitating the literal vantage points we might assume in the real world. There is a lot of contrivance going on.

Real life, amped up

So the convention has some roots in our perceptual and social experience, but filmmakers have streamlined and sharpened it for our uptake. Another example of this process, which I discuss here, involves actors’ eye behavior. Film actors start with normal patterns of looking and blinking, but they modify them in order to signal emotional states and to concentrate our attention on the drama. Similarly, the schema of entering/ leaving a milieu derives from our common experience, but it can be simplified and stylized through cinematic techniques that have no correspondence in our normal experience. All that matters is that the result preserves the core of that schema.

As filmmakers simplify our perceptual and social experiences, they amplify them as well. Movie characters stare at each other more intently than we do in normal life. The actors are stripping off everyday noise (blinks, averted looks) in order to create cleaner, exaggerated signals of mutual attention to the dramatic situation. Likewise, a steep high angle like that ending The Wild One or the pointedly closed curtains of The Hunt for Red October exaggerates the sense of departure and conclusion, giving the action a weight it wouldn’t have in ordinary life.

Why don’t all films use the entry/ retreat convention? I think we should consider such conventions to be tools. They arise in particular filmmaking traditions, perhaps through trial and error, and get refined for different purposes. Some filmmakers might never use them, or knowingly refuse them to create different reactions, or play games with them (as Resnais does at the start of Muriel). But when filmmakers want certain effects, these tools are ready to hand. If you want to ease your audience into the story world, a slow entry pattern works very well. It’s so familiar that the viewer can overlook its contrivance and concentrate on the story information.

So Jeopardy!-style, we have new questions. Has the opening/ closing device spread because it is a very accessible, spontaneously understood convention? Or is it because filmmakers in other cultures have mechanically copied Hollywood? Perhaps it’s like a tool that originates in particular cultural circumstances but which can be useful all over the world. The Phillips-head screw was devised for the US automotive industry but is now a universal gadget. Over time, such tools become more widespread, perhaps dominant. But a tool can always be refused if the task changes.

There’s still a mystery, though. Assuming that viewers understand these image-clusters as signaling beginnings and endings, how did that understanding come about? How, and when, do people learn the conventions? If they are quickly learned, is that because they play into inclinations of our minds?

My best guess for now is this. We tend to think that all artistic conventions are equally hard to learn, but that’s probably not the case. The conventions of Cubist painting demand more effort and knowledge than the conventions of perspective drawing, and that’s probably not just because we’ve seen more perspective pictures across our lives. Likewise, mastering the conventions of Structural Film demands more time and trouble than mastering those of popular genre filmmaking. It seems likely that some conventions rise to dominance because they fit most viewers’ prior inclinations rather well. For example, we are creatures who interact socially in face-to-face manner. Shot/ reverse-shot editing is unfaithful to our ordinary experience in many ways; cuts provide instant changes of viewpoint we can’t achieve in real time and space. But shot/ reverse-shot cutting preserves the familiar social pattern of turn-taking and conversational flow, so it’s comparatively easy to learn.

Still, I don’t have a full answer. My questions bring us back to Molly. If she had seen Snow White before, we might say that she remembered that the film ended at this point. But she hadn’t seen the film before. So does her demand for more indicate that she generalized from her experience of other films? Did she have already a degree of “narrative competence,” allowing her to recognize certain types of cues? Is her competence full or spotty? (Maybe she gets endings, but not characters’ intentions, or goal orientation.) And how did she acquire that competence? Quickly or slowly?

Maybe some researchers have already explored how children master narrative framing of this sort. (I’d welcome correspondence on the matter.) My hunch is that Molly grasped the cinematic convention, perhaps on limited exposure, because she recognized the core perceptual and social experiences it preserves. Leveraging this insight, perhaps, was some understanding of narrative architecture generally. More basically, it may be that as social animals we’re tuned by evolution to detect fairly quickly some constant features of interactions with our peers.

In any case, I’m betting that Molly wasn’t simply mastering a convention cut off from everyday life, like algebraic equations. To learn anything, you already need to know a lot. Cinematic storytelling isn’t, as some semiologists once thought, a highly arbitrary sign system. It piggybacks on our experience of the world–our knowledge, certainly, but also our most routine ways of sensing and thinking. Not least, understanding movies taps skills associated with our social intelligence. More on this in a future entry, I hope.

This is only an anecdote, but I hope it provokes readers to think about the broader issues I raise. I floated these ideas in my closing address for the convention of the Society for Cognitive Studies of the Moving Image, on 5 June 2010. I thank the members of the audience for their contributions to that discussion. Incidentally, this year’s meeting is coming up, in Budapest this June. For more on SCSMI and the sort of issues broached in this entry, go to this category on this site.

My basic argument for a “moderate constructivism” in understanding film conventions is developed in the 1996 essay “Convention, Construction, and Cinematic Vision,” reprinted in Poetics of Cinema (2008), 57-82. I discuss the entry/ withdrawal pattern as a holistic strategy in a later essay in that collection, “Three Dimensions of Film Narrative”, 94-95. An earlier, more fancily titled piece puts the pattern in the context of a different argument: “Neo-Structuralist Narratology and the Functions of Filmic Storytelling” in Marie-Laure Ryan, ed., Narrative across Media: The Languages of Storytelling (2004), 209.

It’s worth mentioning that, like Snow White, the images at the start and conclusion of Le Silence de la mer are enframed by a book–in this case, shots of the original book by Vercors. This iconography is of course common when a film wants to emphasize the literary origins, though in some films, like Dreyer’s, the device of the film as a replay of an already-written text plays a more complicated narrative role. I talk about that in my book The Films of Carl Theodor Dreyer (1981).

The research on children’s understanding of stories is vast and detailed. Alison Gopnik briskly summarizes the evidence that even very young children have surprising narrative competence in The Philosophical Baby (2009), chapters 1 and 2. The pioneering source here, at least for an amateur like me, was Katherine Nelson, ed., Narratives from the Crib (1989).

The Bad Lieutenant: Port of Call New Orleans. As in many films, the final shot addresses the viewer in a comparatively overt way.