Archive for July 2011

Bringing up Hawks

Hawks looms large in any history of American film, but even so…

DB here:

Still scrambling to keep up with all the movies at Bologna’s Cinema Ritrovato, I offer a quick entry on three films in the complete retrospective of Howard Hawks’ early work. Go back here for comments on Cradle Snatchers (1927).

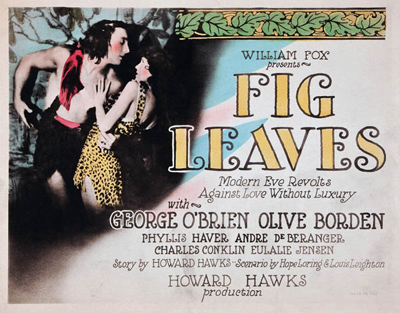

Those who claim that Hawks’ talents are at full stretch in comic situations would find solid evidence in several Ritrovato picks. Fig Leaves (1926) starts in the Garden of Eden, where Adam uses a teetering cocoanut as his alarm clock and the Serpent coaxes Eve into complaining that she simply hasn’t a thing to wear. With its Flintstones anachronisms and genial dinosaurs, the prologue of Fig Leaves makes fun of the hoary device of showing primitive life as a parallel to today, a wheeze Keaton had already exploited in Three Ages (1923).

Our modern Eve’s longing for nice clothes impells her into a job modeling for the house of André, while a shrewd jazz-baby neighbor plays the role of the Serpent in the modern garden. Filled out by Technicolor fashion parades (much praised at the time, but surviving only in contrasty black-and-white), this satirical modern comedy remains a pleasant diversion.

As ever with Hawks, there’s a play on sexual identity. When Adam and Eve wake up in the morning, he’s shot with hard-edged lighting and sharp focus. By contrast, Eve is wrapped in soft light and plenty of diffusion in the manner of the Fox heroines in Borzage and Murnau movies. No surprise there, but later the vaguely Continental dress designer André is introduced in a moderately soft, diffused image, as if he were halfway between man and woman. Although he’s not gay (that role falls to his preening assistant), he’s presented as a sissy as much through the cinematography as through his performance. Then again, most guys look effeminate compared to the brawny Charles Farrell, who is given plenty of chances to strip to the waist. Olive Borden is a matching mate. Variety predicted that “her big, dark, soulful eyes ought to carry her far in the picture world,” but it’s not her eyes that attract André. He’s riveted by the sight of her in a gown, lit from behind so that her figure pops into a curvy silhouette.

E. C. Bentley’s Trent’s Last Case of 1913 was a turning point in the modern detective novel, but you wouldn’t know it by the time that Hawks got around to filming it in 1929. He turns it into a comedy. The murder victim, the millionaire Manderson, uses a book, Unsolved Murders, as a guide to committing suicide in a fashion that will incriminate his secretary, who is in love with Manderson’s wife. The tone is uncertain, and a few cornball low angles with horror lighting are thrown in to goose up some rather overplayed moments.

E. C. Bentley’s Trent’s Last Case of 1913 was a turning point in the modern detective novel, but you wouldn’t know it by the time that Hawks got around to filming it in 1929. He turns it into a comedy. The murder victim, the millionaire Manderson, uses a book, Unsolved Murders, as a guide to committing suicide in a fashion that will incriminate his secretary, who is in love with Manderson’s wife. The tone is uncertain, and a few cornball low angles with horror lighting are thrown in to goose up some rather overplayed moments.

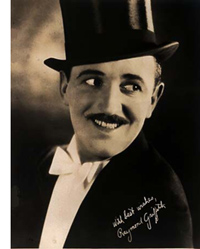

The Trent of the novel set the fashion for the dilettante savant (later incarnated in Lord Peter Wimsey and Ellery Queen), but he remains a somewhat withdrawn figure. In the film, comedian Raymond Griffith plays him as a parody of the chipper playboy, breezy in Griffith’s signature topper and tails. The climax provides a pure travesty of the original. The major innovation of the book, the mistaken solution that takes the sleuth down a peg, becomes a gag in Hawks’ hands. At the climax, Trent denounces one suspect, is proven wrong, moves to another, gets it wrong again, until he has arrived at the truth through elimination. Convinced that he would have sent at least four persons to the gallows, he shrugs off detective work and declares this is his last case.

The film was released in two versions, one completely silent and the other incorporating some sound sequences. The surviving print contains no talking scenes and runs nearly twenty minutes shorter than either 65-minute original. The US release of Trent’s Last Case was evidently quite brief. It remains the strangest and probably the weakest entry in the Hawks filmography.

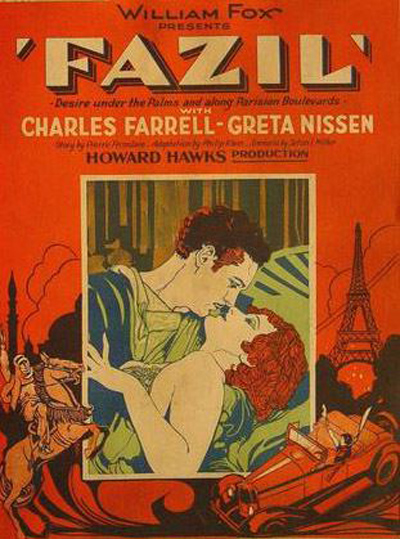

Fazil (1928) could use a lot more comedy, but it brings out Hawks’ interest in vigorous sexual situations. Fazil, a prince from “Araby,” meets Fabienne, a passionate French girl. They marry immediately. Fabienne’s desire for Fazil overcomes her worry that he believes in total domination over her. She defies his commands, and they separate, only to be reunited after she seeks him out in his homeland. When she sees his harem, and then realizes his intent to take a second wife, she again tries to opt out, this time with the help of her European friends. Her escape from his compound climaxes in a gun battle that fatally wounds Fazil. Fabienne accepts a lethal injection from his poison ring so that they may die together, with him finally confessing that he loves her.

This Orientalist farrago, handled humorously at the start (the call to prayer interrupts a beheading), quickly turns serious, even a little decadent. The sexual ambience of the Sheik cycle becomes fairly steamy. After the couple meet at a Venetian party, fade out to the next scene. Fabienne is now sharing Fazil’s bed. Has an affair started? For a little while we’re entitled to think so, until Fazil goes to the window and we see the Eiffel Tower. Soon Fabienne is on the phone talking about her marriage to the prince.

The New York Times review charged that Hawks erred “in his eagerness to display the voluptuous side of a desert chieftain’s life, a series of scenes which would never be missed. “ Actually, I’d miss the moment when Fabienne is introduced to Fazil’s harem. Tracking shots run along the line of scantily-dressed women sizing her up, and reverse shots follow her as she surveys them in fear and fascination, her fingers nervously stroking her upper chest. “August heat,” boasted a Fox ad at the time, “is intensified by the torrid Fazil.” Something like it happened in the June heat of Bologna.

The image surmounting this entry is taken from this year’s extraordinary Ritrovato catalog. Variety‘s review of Fig Leaves was published in the 7 July 1926 issue, p. 16. Bentley’s novel Trent’s Last Case is available free online. The New York Times review of Fazil appeared in the 5 June 1928 issue, p. 21. Fox’s ad for its 1928 slate was published in Variety on 11 January 1928, p. 11.

…But brunettes prefer programmers. Guy Borlée and colleagues.