Archive for December 2011

The ten best films of … 1921

The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse.

Kristin here:

To end the year, we’re continuing our tradition of picking the ten best films not of the current year but of ninety years ago. Our purpose is twofold. We want to provide guidance for those who may not be particularly familiar with silent cinema but who want to do a bit of exploring. We also want to throw in occasional unfamiliar films to shake up the canon of classics a bit.

Like last year, it was strangely difficult to come up with ten equally great films. There were some obvious choices, but beyond them there were a lot of slightly less wonderful items jostling for the other places on the list. The problem had several causes. Some master directors who routinely figure in our year-end ten choices had off-years. In 1921 D. W. Griffith released only one film, Dream Street, a notably weak item. (What I have to say about it can be found on pp. 108-113 of the British Film Institute’s The Griffith Project, Vol. 10.) Ernst Lubitsch released two films that seem like less interesting attempts to repeat earlier successes: Anna Boleyn (a pale imitation of Madame Dubarry) and Die Bergkatze (nice, and I was tempted to include it, but it’s less amusing than the Ossi Oswalda comedies, here and here). Cecil B. DeMille’s The Affairs of Anatol is not nearly as well structured as his earlier sophisticated rom-coms.

In other cases, films simply don’t survive. John Ford released seven films in 1921, all of which are lost.

Death comes calling, twice

Probably the easiest decision was to include The Phantom Carriage (also known as The Phantom Chariot), by Victor Sjöström. As I noted recently, the Criterion Collection has recently issued a beautiful restoration of it (DVD and Blu-ray).

When I first saw The Phantom Carriage, I was probably still an undergraduate. Given its reputation as a great classic, I was somewhat disappointed. No doubt it was partly the battered 16mm copy I watched, but the film is a bit formidable for someone not accustomed to the aesthetic of silent cinema–and especially of the great Swedish directors of the era. Its protagonist, played by Sjöström himself, is a thoroughly, determinedly unlikeable fellow, and the complex flashback structure can be a bit disconcerting on first viewing. But the effort to watch until one “gets” Sjöström is well worth it, since he’s undoubtedly one of the half dozen greatest silent directors.

The story opens on New Year’s Eve with Edit, a young Salvation Army volunteer, on her deathbed. She unexpectedly begs her colleague and mother to fetch the town drunk, David Holm, to her bedside. At the same time, Holm sits drinking in a graveyard as midnight approache. He tells two fellow inebriates the legend of the phantom carriage, the vehicle that picks up the souls of the  newly dead; it is driven each year by the last person to die at the end of the previous year. Holm then dies, and the carriage arrives, with its current driver ready to turn over the job to him. Flashbacks enact both the circumstances of how the heroine met Holm and the happy family whom Holm had alienated through his drunkenness.

newly dead; it is driven each year by the last person to die at the end of the previous year. Holm then dies, and the carriage arrives, with its current driver ready to turn over the job to him. Flashbacks enact both the circumstances of how the heroine met Holm and the happy family whom Holm had alienated through his drunkenness.

It’s a deeply affecting story, wonderfully acted and staged. In most scenes the lighting and staging are impeccable, and the famous superimpositions that portray the carriage and the dead are highly ambitious for the period and impressively executed. The filmmakers have managed to make the carriage, superimposed on real landscapes, appear to pass behind rocks and other large objects. In short, a film that has everything going for it.

Death himself appears in Der müde Tod (literally “The Tired Death,” often called Destiny, or occasionally in the old days, The Three Candles). Here the great German director Fritz Lang hits his stride, and you can expect him to figure on most of our lists from now on.

In Destiny (available on DVD from Image Entertainment) a young woman’s fiancé is killed early on. Death, a sympathetic figure who regrets what he must do, gives her three chances to find another person whose demise can substitute for her lover’s. The three episodes in which she tries take place in Arabian-Nights Baghdad, Renaissance Venice, and ancient China; each story casts her as the heroine and her lover as the hero.Things don’t go well, and Death actually gives her a fourth chance when she returns to the present.

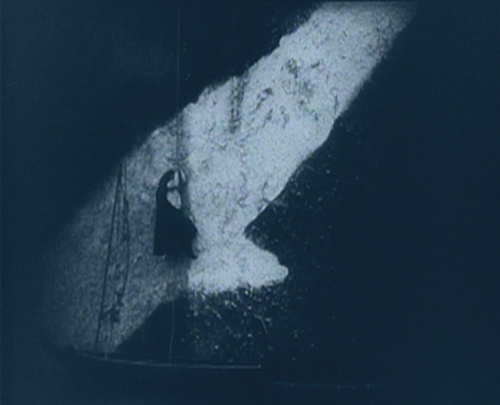

This was Lang’s first venture into the young German Expressionist movement, which had been launched the year before with Das Cabinet des Dr. Caligari. The style shows up only intermittently, perhaps most dramatically in the Venetian episode when the lover shinnies up a rope along a wall painted with a gigantic splash of light. (See bottom.)

Each film has a “happy ending.” I leave it to you to determine which is grimmer.

I’m turning over the keyboard to David now, to describe a film he knows better than I do.

More Northern European drama

Mauritz Stiller alternated urban comedies (Thomas Graal’s Best Film, 1917; Thomas Graal’s Best Child, 1918; Erotikon, 1920) with more lyrical dramas and romances set in the countryside (Song of the Red Flower, 1919; Sir Arne’s Treasure, 1919). Johan (1921) is in the pastoral vein. Its integration of landscape into the drama suggests it was an effort to recapture the production values that overseas critics had praised in Sjöström’s Terje Vigen (1917) and The Outlaw and His Wife (1918). Like the Sjöström films, however, Johan offers more than splendid spectacle; it’s the study of the undercurrents of a marriage.

At the core is a love triangle. The fisherman Johan is the somewhat thick-headed son of a domineering mother. He is fond of the girl Merit, whom he and his mother rescued as a waif and brought into their household. But this synopsis is actually skewed, because Stiller and the scriptwriter Arthur Norden have told the story in an unusual way.

At the core is a love triangle. The fisherman Johan is the somewhat thick-headed son of a domineering mother. He is fond of the girl Merit, whom he and his mother rescued as a waif and brought into their household. But this synopsis is actually skewed, because Stiller and the scriptwriter Arthur Norden have told the story in an unusual way.

We’re introduced to the couple by following the rogue Vallavan’s entry into the town; Johan seems almost a secondary character until Vallavan leaves. When Johan breaks his leg, Merit agrees to be his wife. Now we’re attached to her standoint and see her life of drudgery under the petty tyranny of Johan’s mother. Vallavan returns, and Merit falls under his spell. Taking her hand, he says, “I want to rescue you.” After she has fled with him, Johan clumsily wanders the rocky shore. “Will I ever see Merit again in this life?” The narrational weight passes to him as he decides to pursue the runaways.

Like Sjöström’s Sons of Ingmar (1918-1919), Johan presents marriage as a trap for unwary women. Our shifting attachment, from Vallavan to Merit and eventually to Johan, allows us to see the situation in many dimensions. As a sort of parallel, Stiller makes fluid use of the now solidly-established conventions of continuity editing. Vallavan’s seduction of Merit is played out in tense shot/ reverse-shot, and there’s an engrossing moment involving delicate shifts in point of view. When the bedridden Johan sees Merit leaving, after his mother has cast her out of the house, he must smash a window pane with his elbow in order to call to her. Stiller’s dynamic eyelines, direction of movement, and precise changes of camera setup here show that he had mastered the American style.

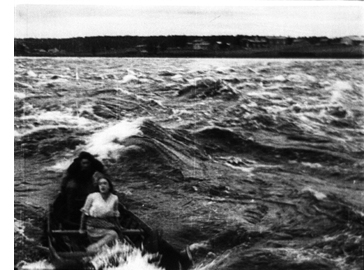

Alongside this finesse, there is still plenty of outdoor action, highlighted when Vallavan rows Merit away in the tumultuous river. Filmed from another boat, the actors are all but engulfed by the waves. It was presumably scenes like this that the parent company, Svensk Filmindustri, hoped would attract international attention. At this period Svensk, dominant in the local industry, was hoping to sell its films on a global scale. That ambitious plan failed, but it left us with many outstanding movies and soon brought Stiller, along with Sjöström, to Hollywood.

Johan is available on a Region 2 PAL DVD, coupled with Kaurismaki’s Juha, another adaptation of the Juhani Aho story.

The joys of small-town life

Last year I included two films by William C. deMille, the considerably less famous brother of Cecil B. The year 1921 saw the release of what is today his best-known film, Miss Lulu Bett. It was based  on the popular novel and play by Wisconsin author Zona Gale, who received her MA here at the University of Wisconsin-Madison and in 1921 became the first woman to win a Pulitzer Prize for drama. The story centers around the heroine, a spinster who lives with her sister’s family, including her niece, nephew, and brother-in-law, Dwight Deacon. Dwight is a tyrant who delights in taunting Lulu over her unwed status, and the rest of the family treats her as a servant.

on the popular novel and play by Wisconsin author Zona Gale, who received her MA here at the University of Wisconsin-Madison and in 1921 became the first woman to win a Pulitzer Prize for drama. The story centers around the heroine, a spinster who lives with her sister’s family, including her niece, nephew, and brother-in-law, Dwight Deacon. Dwight is a tyrant who delights in taunting Lulu over her unwed status, and the rest of the family treats her as a servant.

The return of the husband’s globetrotting younger brother Ninian after a twenty-year absence injects some life into the situation. Taking the family out to dinner, he realizes just how boring the family is (right), and to liven things up, suggests that he and Lulu perform mock marriage vows. Dwight realizes that the ceremony is legally binding, and, already attracted to Lulu, Ninian suggests that they treat it as a real marriage. Desperate to escape her dreary situation, Lulu agrees. The relationship proves agreeable, and Lulu declares that she will learn to love Ninian–when he reveals that he had previously been married, though he doesn’t know whether his first wife is dead (in which case he and Lulu are married) or alive (in which case they aren’t). Unwilling to take a chance, Lulu returns to the Deacons, who consider her disgraced and treat her even worse.

The film avoids melodrama. Ninian is not a villain; he’s kind to Lulu and sorry for the position he’s placed her in. It remains to Lulu to summon the gumption to leave the family and find her own happiness.The whole thing is told with restraint and little touches of humor that draw the viewer into a deep sympathy with Lulu’s plight.

Lois Wilson’s performance as Lulu is crucial in this. She is at once plain enough that we can believe she is in danger of becoming an old maid and pretty enough to plausibly attract the attention of the handsome local schoolteacher. Wilson’s most prominent role came two years later, when she starred as the heroine in James Cruze’s The Covered Wagon.

Miss Lulu Bett is the only one of William’s films available on DVD, paired with Cecil’s Why Change Your Wife? As so often happened, William seems to take a back seat to his famous brother, but the pairing is a logical one, in that William wrote the script for Why Change Your Wife?

Another small-town drama of the same year is Lois Weber’s The Blot. In 1981, when I was teaching a course on American silent film at the University of Iowa, I wanted to quickly demonstrate to the students that the silent period was not an era of exaggerated acting and naively melodramatic plots. I showed a double feature of The Blot and King Vidor’s Wine of Youth (1924). The latter portrays changing sexual mores through the story of three generations of the same family, with a young woman of the Roaring Twenties questions the necessity of marriage when she discovers that her mother is contemplating divorce. I think Wine of Youth (unfortunately not available on video) and The Blot convinced my class that silent films could be both sophisticated and subtly acted.

The “blot” of Weber’s title refers to the notion that people in professions depending on intelligence and education are poorly paid, while tradespeople and children from rich families are well off. The representatives of the underpaid are a college teacher, Prof. Griggs, and a young, idealistic minister. The parallels to recent events are striking. College professors may not be so badly paid as in the 1920s, but the move toward institutions of higher learning depending on adjunct lecturers has created a similar issue. In general, the income gap is familiar: the rich young wastrels taking Prof. Griggs’s course represent what we now call the one percent, while the professor and minister live on a much lower plane.

Weber’s drama is not quite this bald, however. Various levels of prosperity are represented. The professor’s family lives in shabby gentility, his wife grimly struggling to keep food on the table and his daughter Amelia, in delicate health due to a lack of nourishing food, working in the local library. Their neighbors are the family of a successful shoemaker, who live well but lack education. The shoemaker’s wife in particular resents what she perceives as intellectual snobbishness in the professor’s family and takes every opportunity she can to flaunt her comparative wealth.

Her son, however, has a crush on Amelia, as does the poor minister. Into this situation comes Phil West, the professor’s rich but indolent and mischievous student. Also attracted to Amelia, Phil for the first time encounters real poverty and is  shocked by it. As the plot develops, Amelia falls ill, and her mother’s increasingly desperate efforts to obtain the food necessary to nurse her to health become one of the main threads of the drama. To say that a large part of the action in the second half of the film centers on Mrs. Griggs’s temptation to steal a chicken from her neighbors might make the situation seem a trifle comic, but Margaret McWade’s remarkable performance vividly conveys the wife’s struggle in the face of real lack and her humiliations in the eyes of the shoemaker’s gloating wife. When Mrs. Griggs succumbs to temptation, the result is a brief but wrenching scene.

shocked by it. As the plot develops, Amelia falls ill, and her mother’s increasingly desperate efforts to obtain the food necessary to nurse her to health become one of the main threads of the drama. To say that a large part of the action in the second half of the film centers on Mrs. Griggs’s temptation to steal a chicken from her neighbors might make the situation seem a trifle comic, but Margaret McWade’s remarkable performance vividly conveys the wife’s struggle in the face of real lack and her humiliations in the eyes of the shoemaker’s gloating wife. When Mrs. Griggs succumbs to temptation, the result is a brief but wrenching scene.

The plot is remarkably dense and unpredictable. Every scene involves glances that lead to new knowledge or serious misunderstanding, deflecting the plot into new directions. Early on it is impossible to say which of the three young men Amelia will end up with, and even by the late scenes, when only two plausible romantic candidates remain, we have no idea which she will pick. As in many of Weber’s films, she does a bit of preaching about the social problem involved, but in The Blot she leaves this until near the end and gets it over quickly and fairly believably. The considerable but gradual change in Phil’s attitude toward education and the problems of poverty is also made believable. The prosperous neighbor’s change of attitude may seem a bit sudden, though it is somewhat motivated by a line early on.

But on the whole, even more than with Miss Lulu Bett, this is an absorbing story with characters for whom we care. Weber uses motifs as skillfully as any director in the early phase of the classical Hollywood cinema. Watch in particular how many different ways she uses the Griggs family’s cat and her two kittens: to demonstrate the family’s poverty, to be the main means of the neighbor lady’s spite, to introduce some comedy, and so on. Even more pervasive is the way that shoes become tokens of characters’ various social positions.

The Blot is available on DVD from Image. Those interested in Weber as a director should note that next summer’s Il Cinema Ritrovato festival in Bologna plans a retrospective of her work.

Which is best? Damfino.

In past year-end lists, we’ve watched Harold Lloyd, Charles Chaplin, and Buster Keaton creeping toward their great features of the 1920s. This year two of them move cautiously into longer films, and the other releases two more terrific one-reelers.

The Boat is one of Keaton’s most admired shorts. In it, he, his wife, and their two young sons build a boat, the Damfino, and unwisely launch it on the open ocean. Everything that can go wrong does: the life-preserver sinks, the anchor floats, and naturally a storm hits. The wife’s pancakes aren’t edible, but one temporarily patches a leak. Throughout the intrepid band carries on against all obstacles.

Less perfect but more dazzling and (perhaps) funnier is The Playhouse. The premise of a small variety theater creates an episodic, messy narrative, but it allows Keaton to play out a series of four “acts.” Initially we see Keaton buy a ticket and enter an auditorium where the audience, the orchestra, and all the performers are played by “Buster Keaton.” As one of the audience members remarks, “This fellow Keaton seems to be the whole show,” which is true in more way than one. The multiple images of Keaton were accomplished entirely in the camera, by cranking back the film with precise timing and uncovering a different part of the lens at each pass. The precision when one Keaton figure talks to or dances with another is amazing.

This all turns out to be a stagehand’s dream. (Keaton being the stagehand.) The multiplication motif returns as an act involving two pretty girls who happen to be twins–something Buster  doesn’t know, making his encounters with them ever more baffling. Later an orangutan escapes, and Buster dons make-up and costume to replace him. All hilarious stuff, though unfortunately the final act, a Zouave Guard drill, is the least funny one. Still, it’s a terrific film with a big dose of the surrealist quality that will run through the later shorts and the features.

doesn’t know, making his encounters with them ever more baffling. Later an orangutan escapes, and Buster dons make-up and costume to replace him. All hilarious stuff, though unfortunately the final act, a Zouave Guard drill, is the least funny one. Still, it’s a terrific film with a big dose of the surrealist quality that will run through the later shorts and the features.

The Boat is included on Kino’s disc of The Navigator and The Playhouse with their out-of-print DVD of The General. Still in print, however, is Kino’s eleven-disc set of the features and shorts. For those in the UK and other region-2 countries, Eureka! has a “Masters of Cinema” three-disc set, “Buster Keaton: The Complete Short Films 1917-1923,” which includes many of his earlier films with Fatty Arbuckle.

The year saw Lloyd and Chaplin make their first feature films, though both releases were still fairly short. I’m not really counting A Sailor-Made Man as one of the top ten of the year, since it’s a delightful but decidedly light item. Just another reminder that Lloyd is inching toward greatness.

Lloyd presents his “glasses” character as a brash young man who impulsively proposes to a rich man’s daughter. When the father demands that he get a job to prove his worth, Harold enlists in the navy. Highjinks ensure, culminating in a lively chase-and-rescue scene when the heroine gets kidnapped by a lecherous Arabian sheik.

Lloyd presents his “glasses” character as a brash young man who impulsively proposes to a rich man’s daughter. When the father demands that he get a job to prove his worth, Harold enlists in the navy. Highjinks ensure, culminating in a lively chase-and-rescue scene when the heroine gets kidnapped by a lecherous Arabian sheik.

The shipboard scenes allow Harold to get in some funny bits, mainly involving him trying to be tough and succeeding at first by sheer accident. Later, however, he is inspired by the heroine’s danger to become a real rescuer. It’s a sign of bigger things to come.

New Line’s Harold Lloyd boxed set is out of print, but you can still get the volumes separately. A Sailor-Made Man is in Volume 3, along with such delights as Hot Water and For Heaven’s Sake.

Chaplin’s first feature, The Kid, is a skillful blend of the rough-and-tumble slapstick that had characterized his early shorts and the sentimentality that would gradually become a more prominent trait of his films. A unmarried woman (played by Edna Purviance, the elegant beauty who made such a contrast with the Little Tramp in many of his films) abandons her infant in an expensive car which happens to get stolen moments later. Charlie finds the baby, and after numerous attempts to get rid of it–including a brief contemplation of an open storm-sewer grate–decides to raise it. The baby grows into the adorable and amusing Jackie Coogan.

Chaplin’s first feature, The Kid, is a skillful blend of the rough-and-tumble slapstick that had characterized his early shorts and the sentimentality that would gradually become a more prominent trait of his films. A unmarried woman (played by Edna Purviance, the elegant beauty who made such a contrast with the Little Tramp in many of his films) abandons her infant in an expensive car which happens to get stolen moments later. Charlie finds the baby, and after numerous attempts to get rid of it–including a brief contemplation of an open storm-sewer grate–decides to raise it. The baby grows into the adorable and amusing Jackie Coogan.

In the meantime, the mother has become a rich singer, and coincidentally she comes to the slums doing charitable work. The authorities eventually try to remove the Kid to an orphanage, and later a flop-house proprietor turns him in to receive a reward. Still, Chaplin doesn’t milk the pathos, and a happy ending duly arrives.

The Kid is available in a decent print along with A Day’s Pleasure and Sunnyside on the “Charlie Chaplin Special” DVD. Our recording off Turner Classic Movies strikes me as being slightly better quality, so you might keep an open to see if they reshow it. It was also announced this week that The Kid has been added to the National Film Registry of the Library of Congress.

Fuzzy movies, big and small

Soft-style cinematography had been tried in some films of the late 1910s, most notably in Griffith’s Broken Blossoms. But in the 1920s it spread. In Hollywood, it was mainly a technique for making beautiful images and especially for creating glamorous close-ups of actresses. In France, it was a way of tracking a character’s inner life.

Vicente Blasco Ibáñez’s 1918 novel, The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse was a huge bestseller, and the first film adaptation in 1921, directed by Rex Ingram, was equally successful. To many, it is remembered for having made a super-star of its main actor, Rudolph Valentino. Anyone who has seen him as the caricatured Latin Lover of his later films will be pleasantly surprised to discover that the man could act, as could his leading lady, the lovely Alice Terry.

Ingram was the quintessential middlebrow director of the 1920s, doing big-budget, respectable adaptations of popular literature (e.g., Scaramouche, The Prisoner of Zenda). To me, Four Horsemen escapes the stodginess of the later films, at least to some extent (as does his other 1921 film, The Conquering Power). It and the other film in this section were borderline cases, chosen as much for their historical importance as their quality, perhaps, but definitely worth watching.

One of Four Horsemen‘s greatest strengths is its photography. Ingram worked consistently with one of the greatest cinematographers of the 1920s, John F. Seitz, who created glowing images of  sets and actors with selective lighting and all sort of means of softening the image. This film, more than Broken Blossoms, brought the soft style into vogue. It eventually culminated in the Dietrich films of Josef von Sternberg before a more hard-edged look came to dominate the 1940s.

sets and actors with selective lighting and all sort of means of softening the image. This film, more than Broken Blossoms, brought the soft style into vogue. It eventually culminated in the Dietrich films of Josef von Sternberg before a more hard-edged look came to dominate the 1940s.

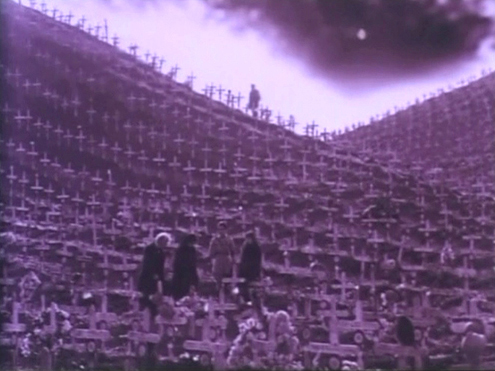

Four Horsemen was also an early entry in the anti-World War I genre of the 1920s and 1930s. Its final scene in a vast military cemetery of identical white crosses remains a powerful one. (See above.) Here, however, the Germans are still stereotypes, militaristic puppets with no redeeming features. Even that notion would gradually change, however, until nine years later All Quiet on the Western Front could recount the war from the German point of view.

Four Horsemen is available on DVD on demand from Amazon, supplied on DVD-R. In the same format, one can order it on a set with a documentary on Valentino. The reviews of the latter suggest that the visual quality is good.

(For more on this photographic style, see my “The soft style of cinematography,” in The Classical Hollywood Cinema, pp. 287-293.)

I’m not a huge fan of Marcel L’Herbier, and I’m not entirely sure that El Dorado is a full-fledged  masterpiece. But it has many virtues, and arguably it’s historically important as the first film of the French Impressionist movement to thoroughly explore ways in which camera techniques could convey perceptual and psychological states. It focuses largely on Sibilla, a singer-dancer who is the main attraction in a tawdry Spanish bar. She and some other women are performing as the story begins, but Sibilla is distracted by worries about her sick son. L’Herbier experimented with tracing her attention by placing gauzy filters over her face when she starts thinking of the boy. In the frame at the left, for example, she is in sharp focus when onstage, but as she passes into the backstage area, she goes fuzzy.

masterpiece. But it has many virtues, and arguably it’s historically important as the first film of the French Impressionist movement to thoroughly explore ways in which camera techniques could convey perceptual and psychological states. It focuses largely on Sibilla, a singer-dancer who is the main attraction in a tawdry Spanish bar. She and some other women are performing as the story begins, but Sibilla is distracted by worries about her sick son. L’Herbier experimented with tracing her attention by placing gauzy filters over her face when she starts thinking of the boy. In the frame at the left, for example, she is in sharp focus when onstage, but as she passes into the backstage area, she goes fuzzy.

In a way this is a somewhat silly, literal notion, and yet it’s exciting to see filmmakers exploring new devices relatively early in film history. Gauzy filters, distorting mirrors, slow-motion superimpositions, rhythmic cutting, and subjective moving camera were soon to be in common use by a small group of French directors. El Dorado was also the first film to be filmed within the Alhambra, which lends it considerable visual interest.

If we’re still writing this blog in 2019, our list will probably include the culminating film of the movement, and arguably L’Herbier’s best silent film, L’Argent.

Not many French Impressionist films are available in the U.S. If you have a multi-region player, El Dorado is paired with L’Herbier’s earlier L’homme du large (1920) on a French DVD.

Tigers and lepers and a mysterious yogi

We tend to think of serials as having many episodes and being low-budget additions to programs. That’s the American model, but in Europe things were different. Louis Feuillade’s serials are among the gems of the 1910s. In Germany, serials tended to have fewer episodes but bigger budgets–much bigger. Many were only two parts, most famously Dr. Mabuse, der Spieler (coming next year to our top-ten list) and Die Nibelungen (coming in 2014). Lang had launched into serials with Die Spinnen (1919 and 1920). The two parts have terrific things in them, but Lang never went on to finish it.

He was, however, still collaborating on screenplays for director Joe May, who specialized in epic serials set in exotic countries and starring his wife, Mia May. Highly entertaining though these films are, they are largely forgotten, even by most lovers of silent cinema. Das indische Grabmal is the exception, though even now few have had a chance to see it. In 1996 it was shown at “Il Gionate del Cinema Muto” festival in Pordenone and was all too briefly available on an Image DVD (as The Indian Tomb) now out of print. Track it down if you can.

Full of the stars of its day, Das indische Grabmal is set largely in India, and its plot was inspired by the Taj Mahal. A ruthless maharajah (played with relish by Conrad Veidt) cloaks his cruelty under a veneer of European courtesy. He plots to shut his unfaithful princess (Erna Morena) in a beautiful tomb along with her lover (Paul Richter, better known to modern audiences as Siegfried). He calls in a famous European architect (Danish star Olaf Fønss) to build it, and the architect’s fiancée (Mia May), rightly fearing dirty work afoot, follows. One pit full of tigers and one of lepers lie waiting to endanger the visitors. The sets are beautiful. The Germans by this point could do them at full scale (above left) and as marvelously deceptive miniatures (above right). Das indische Grabmal is constantly entertaining and perhaps the best of its type, at least of the films we have access to.

Lang directed a two-part remake of this film in 1959. Both are good, but I prefer the silent one.

Some runners-up

As I mentioned, we had trouble narrowing down our list this year. Here are some others that could have replaced some of our prime choices. The German stage director Leopold Jessner adapted the play Hintertreppe (Backstairs). It’s a Kammerspiel, set in two apartments and the courtyard between them, and concerns a simple love triangle among a maid, her absent lover, and the postman who loves the maid so much that he forges letters from her sweetheart to keep her happy. Antti Alanen kindly reprinted my notes on the film here.

Carl Dreyer’s third feature, Leaves from Satan’s Book, remains one of the most widely-admired variants on the Intolerance formula of presenting thematically linked historical episodes. The dynamic final last-minute non-rescue shows that Dreyer learned a good deal from Griffith’s crosscutting too. Leaves is available on a Danish DVD with English subtitles and an alternate ending. Murata Minoru’s Japanese feature Souls on the Road, another exercise in complex crosscutting, and Feuillade’s polished L’Orphéline are solid runners-up as well. Neither is available on commercial DVD, as far as we know.

Destiny.

Home for the holidays

Pina. Photo Laurent Philippe.

DB here:

Kristin and I sometimes write about a film at a festival long before it reaches commercial distribution. As the year ends, we thought some readers might be interested in catching up with what we wrote about items now making the rounds of art theatres and film festivals. These are notes, not really analyses, but we try to introduce some ideas along with our judgments. All of these are films we admire considerably.

On Pina. Academy Award nominee for best documentary.

On Once Upon a Time in Anatolia. Turkey’s Foreign-Language Academy Award submission.

On Mysteries of Lisbon. Coming to DVD and Blu-ray in January. DB’s tribute to Raúl Ruiz is here.

On A Separation. Iran’s Foreign-Language Academy Award submission. DB also wrote on About Elly, an earlier film by Asgar Farhadi that deserves distribution, if only on DVD.

On This Is Not a Film. We wrote about Panahi’s perilous situation exactly a year ago here.

On The Turin Horse (above). Hungary’s Foreign-Language Academy Award submission. For more on Tarr, check the links on the right.

Coming up next week: Our annual year-end review of the ten best films of ninety years ago.

After the New Year starts, we’ll continue the series of entries about how digital cinema is changing film culture, with pieces on arthouse and repertory exhibition, film festivals, and home consumption of films. Plus observations on actors’ hands, film directing as problem-solving, some peculiarities of film reviewers, and other matters of weighty and not-so-weighty consequence.

In the meantime, we wish our readers the best for the holidays!

Meet Me in St. Louis.

Pandora’s digital box: The last 35 picture show

The Goetz and Goetz Junior Theatres, Monroe, Wisconsin, 1936.

DB here:

Eighty years ago the Goetz Theatre of Monroe, Wisconsin opened its doors. Last Sunday it screened the last 35mm prints it will ever show. On Tuesday, it became a digital cinema.

I sometimes find myself wishing I had been alive and sentient when exhibitors migrated from storefronts to dedicated venues in the 1910s, when they wired silent-movie venues for talkies (late 1920s-early 1930s), or when they converted to widescreen in the early 1950s. (For this last change, I was around but not sentient.) Think of all I could have learned about the stuff I study at a long remove now. Today I’m living through another time of technological upheaval, so I’m trying to catch up with it.

There are about 39,000 screens operating in the US, and about half are controlled by five major chains: Regal Entertainment Group, AMC Entertainment, Cinemark, Carmike, and Rave. Most of the screens are in population centers and are housed in multiplexes, which introduced economies of scale to the exhibition sector. Those economies make it relatively easy for the big chains to convert to digital. As a follow-up to my post on digital conversion at a local AMC multiplex (here), I wondered how the process affects a small-town exhibitor. After all, thousands of screens across the country belong to regional circuits or are mom-and-pop operations.

So I went to Monroe.

Local boys make good

Wisconsin is more than cheese and beer, but both have shaped the history of Monroe. The town grew in the 1890s with an influx of German-speaking Swiss immigrants, like those who founded the much smaller New Glarus. In the middle of farming country, Monroe became a center of signature Wisconsin commerce. It had the Joseph Huber Brewing Company, founded as the Bissinger brewery around 1845. It’s the home of the Berghoff line and other tasty beers. In 1926 an enterprising UW graduate modernized the town’s cheese industry by creating the Swiss Colony, a mail-order firm that offered cheese, sausage, and baked goods. The Swiss Colony still employs several thousand Monroe citizens and now holds a considerable portfolio of other brands.

While many small towns are shrinking, Monroe has had a steady population of about 10,000 since 1980. It’s a very pretty place, with a well-preserved town square centering on a towering Romanesque county courthouse. Elsewhere are some well-wrought Victorian homes. The town’s Swiss heritage is preserved in several restaurants, social clubs like Turner Hall, and civic events, notably the Cheese Days celebration.

Monroe had a succession of movie houses. Before 1920 there were the Nickelodeon, the Star, the Crystal, and the Lyric. Several of these were managed or owned by Leon Goetz, an early traveling film entrepreneur. He had run films in tent shows and town halls before settling in Monroe. In 1916 he opened the Monroe, the first movie house he built from scratch.

Leon Goetz was a risk-loving man. To build a 500-seat film theatre in a town with about 4500 people reflects not only the growing popularity of movies but a conviction that the business had a future. In addition, the many farms and little towns around would supply customers; Monroe is the county seat of Green County, so people came here to transact business as well as to shop. Then as now, the nearest competitors to a Monroe theatre were over twenty miles away.

Leon Goetz was a risk-loving man. To build a 500-seat film theatre in a town with about 4500 people reflects not only the growing popularity of movies but a conviction that the business had a future. In addition, the many farms and little towns around would supply customers; Monroe is the county seat of Green County, so people came here to transact business as well as to shop. Then as now, the nearest competitors to a Monroe theatre were over twenty miles away.

With his brother Chester as partner, Leon owned or managed other theatres in the area, including ones in Beloit and Janesville. The brothers’ biggest triumph, however, was building the Goetz Theatre. Opening on 2 September 1931, it was of semi-Moorish design, with faux balconies and moody cloud-and-star lighting on the ceiling. Light brown brick and darker brown terracotta inlays finished the outside. The lobby was forty feet high, with a gold finish and many trappings and fixtures.

Some unexpected innovations included seats equipped with earphones for the hard of hearing. The screen was 20 feet wide and fifteen feet tall. Accounts of the size range from 800 to 1000 seats. In all, the Goetz was said to have cost $125,000.

The Monroe had presented sound films using a system of Leon’s devising, but the Goetz was a step up, as the editors of the Monroe Evening Times indicated:

It should raise inestimably the respect with which talkies are looked upon locally and attract many persons who heretofore did not care to see pictures under the conditions in which they were shown.

The Goetz has run ever since. It’s said to be the oldest continuous family-operated movie house in the Midwest.

Leon retired to Florida but Chester stayed in the business, opening the Goetz Junior on Christmas day, 1936. It was “ultra modern,” as it advertised itself, with the Western Electric Mirrophonic sound system and using streamlined design elements, like glass brick. Holding only 275 seats, it sometimes showed films not screened at the Goetz across the street, but other times it would screen the same films–sometimes on the same night, with reels rushed back and forth.

Soon Chester had competition from the Chalet, a 500-seat house around the corner. According to local memory, Chester cut ticket prices and then bought the floundering Chalet as a third Goetz house. Chester’s sons Robert and Nathan joined the business. Under Robert’s leadership, their company built the Sky-Vu Drive-in in 1954, and it too has been running without interruption every summer.

The postwar decline in movie attendance may have hit the family’s circuit. The Chalet and the Goetz Junior closed. In the 1980s and 1990s two screens were added at the Goetz, but unlike most old theatres that went multi-screen, the venue wasn’t split up. The new houses were converted from adjacent retail spaces. Visit the Goetz today and you’ll see the original auditorium. There are fewer seats, but it’s still enormous, as you can see from the front.

The third generation

Robert “Duke” Goetz. Behind him, counterclockwise, pictures of Conrad Goetz, Nathan as a child, Robert as a child, young Chester, and John. In the center, Chester Goetz.

For many years the downtown theatre and the Sky-Vu have been managed by Robert “Duke” Goetz, Robert’s son. He has a masters degree in landscape architecture from Harvard, but he’s been running the family business. He does everything from programming the movies and designing the website to wrench-and-hammer work on the place. He’s worked on heating, carpentry, and acoustic matters. Talk with him and you’ll hear about the tough times small-town exhibitors have faced over the last two decades. I learned as well some pressures on exhibition that I never thought about.

Duke Goetz has a commitment to showmanship and quality of presentation. The Goetz website has old-fashioned razzle-dazzle, including neon colors. (Chester liked bright colors in his houses.) On another page of the site you’ll see this:

Last Friday I saw Duke tell a gaggle of teenagers to shut off their cell phones, and he watched to make sure they did. The same pursuit of a good movie experience shows in Duke’s special attention to sound. Convinced that DTS is the best sound system for his venues, he has outfitted his smaller auditoriums with hard-hitting speaker systems. He installed tip-back seats, stadium seating in one house, and one belt-driven projector for steadier images.

Despite the commitment to quality, and programming that brings in family fare matched to local tastes, business has been rocky. Duke recalls some high points: 1993, when Jurassic Park did spectacularly at both the Goetz and the Sky-Vu; 1998, when Titanic brought in as many as a thousand viewers a night; and 2002, his best year in recent memory. That year was an exceptional spike for the industry as a whole, with estimated admissions of 1.57 billion, so just about anything less looks like a decline. Kristin talks about this effect here.

Duke’s business stayed flat but solid until 2007, when both the drive-in and the downtown screen began to slump. Business flattened out at a lower level through 2011. The only bright spot this year was Twilight: Breaking Dawn; the midnight premiere drew about 150 customers, mostly high-schoolers.

A good night at all three indoor screens is 300-350 tickets, but the Sky-Vu can reliably draw many more. Duke recalls one evening when the drive-in had over 1100 customers and sold 114 handmade pizzas. Today, even with competition from another local drive-in, the Sky-Vu’s summer schedule bolsters the bottom line significantly.

Why the falling off in recent times? I had expected the standard macro-explanations: the internet, video games, etc. But Duke’s main rival, he believes, is sports. In a town like Monroe, high school sports are central to community life, so Friday night football and basketball games draw not only teens but parents. With the rise of women’s athletics, the middle and high schools schedule plenty of games across the weekend. Add in the fact that televised football in the fall breaks up Saturday (the UW Badgers) and Sunday afternoons (the Packers), and you have a client base that isn’t focused so much on movies. Even the Christmas-New Year corridor, normally a brisk business period, is likely not to help much this time. The New Year starts on a weekend, so that the Packers’ final game on Sunday and the Badgers in the Rose Bowl on holiday Monday will compete with Duke’s screenings.

After three tough years, Duke looks at things realistically. He hires part-time staff to project, sell concessions, and keep an eye on the house, so he’s his only full-time employee. He adds: “I have not been paid since August 2010.” Digital, he admits, is chancy in this business climate. “But without digital, I’m gone.”

Duke goes digital

Duke Goetz saw his first digital screening around 2000 at a convention of the National Association of Theatre Owners (NATO). What attracted him was the edge-to-edge screen brightness. Judging by what I saw on Friday (from down front), the 1.85 image in 35mm at the Goetz is quite sharp, but Duke had long been unhappy with the inevitable falling-off of light toward the edges of any film display. The tendency is exaggerated in anamorphic (2.40) films, which have become more common. And the bigger the screen, the greater the tendency toward a hot spot in the center. In addition, Duke liked the punchier color in digital.

So he was intrigued. “I’d have loved to have done it ten years ago.” But then there was still debate about trustworthy delivery systems (the Net? satellite?) and the cost was astronomical, about $125,000 per projector. Last summer, though, it became clear that the digital wave was cresting, and time was running out for 35mm film. Also running out were the plans for the Virtual Print Fee, whereby the studios partially subsidize the cost of a theatre’s changeover.

This fall Duke took the plunge, arranging for three new NEC projectors from companies and installers he’s known for years. His final analog shows were last weekend. On Monday all houses were closed. By Tuesday night, the Goetz was running a digital copy of New Year’s Eve, which it had run in 35mm only a couple days before. By this coming weekend, all the digital screens are expected to be in action. Duke isn’t going with 3D, partly because he can’t justify the upcharge and partly because he’s not convinced it attracts enough extra business.

I was there for the Friday night 35 shows, and I re-visited on Tuesday. The whole changeover was less dramatic than I expected. In two of the houses, the old projectors were simply moved aside and the new ones sat stolidly in their place.

The gigantic platters were stacked in the hallway.

Reels, rewinds, and splicers sat in corners. All of the 35mm projectors were relatively new, but now one is now in the lobby as a historical artifact.

Duke thinks that digital will be even better for the Sky-Vu. The big screen is a problem for dimness and edge-to-edge brightness, but it should respond well to a digital beam. An indoor screen is porous to allow sound through, but that means that some light is lost. A drive-in screen is solid and should reflect light better. The brilliance of the digital illumination should also help counter chronic drive-in problems like fog, ambient light, moonlit nights, and some flaws on the screen.

The Goetz attendance flattening is part of a larger trend. The box office of 2011 has been weak, and for several years the total domestic admissions have hovered between 1.3 and 1.5 billion. Box office takings are up chiefly because of raised ticket prices, particularly for 3D and Imax. Professional predictors are suggesting that this year’s ticket sales will end up about the same as last year’s.

It would be easy for us cinephiles to bemoan what happened between Sunday and Tuesday in Monroe, Wisconsin. We celebrate the look and feel of film, and we’d like to see old picture palaces become temples dedicated to 35mm. But we don’t pay the shipping and heating bills for those houses; we don’t dicker with bookers who won’t let us have prints when we need them. We like the idea of film surviving, but the practical people who actually deal with exhibition day by day can’t afford to satisfy our tastes.

And we purists would doubtless be scandalized at what film prints looked like when they made their way to the Goetz in the old days, six months or more after release. The Goetz Junior opened with Eddie Cantor’s Strike Me Pink nearly a year after it premiered in Manhattan. In April 1956 the Chalet was running a 1951 Roy Rogers movie. Take a time machine back to the 30s or 40s or 50s and you’ll probably watch a choppy, scratchy print. In comparison digital starts to look pretty good.

I’d like to see Duke succeed. Monroe’s theatre reminds me of the single screen of my childhood, Schine’s Elmwood in Penn Yan, New York. That theatre is long gone, so part of me hopes that somewhere a local movie house can still bring in the community–whether it’s showing film, 2K, Blu-ray, or vanilla DVD. When I was a boy, I wouldn’t have cared how those images got on the screen. In a town like Monroe, the theatre, and the neighborly spirit it represents, is as important as the emulsion. One item of evidence is my 1936 photo up top, taken from the Goetz website. Down past the Hollywood Inn, which I wish I could visit now, maybe you can make out the Goetz marquee: TODAY 2 BIG FEATURES IN GERMAN.

Duke closed out his 35mm shows on the worst weekend exhibitors had seen since fall 2008. Will digital bring Monroe area customers back? Once people realize that they will get high-quality presentation in their home town, perhaps they won’t drive half an hour to Freeport or an hour to Madison. But best not to prophesy. Duke realizes he’s taking the same sort of risk that Leon and Chester took when they built the Goetz at a price of what would be $1.7 million today. “My motto,” he says, “is go digital or die.”

This is the second in a series of entries on the conversion of filmmaking, distribution, and exhibition to digital formats.

Leon Goetz is also credited with producing at least two films, Ten Nights in a Bar Room (1931) and The Call of the Rockies (1931).

I thank Duke Goetz and Mrs. Robert Goetz for talking with me about the past and present of the family business. Other information comes from volumes of The Film Daily Yearbook and issues of The Monroe Evening Times of 1 September 1931; 23 December 1956; 22 October 1981; and 15 May 2001. Also very helpful was Pictorial History of Monroe, Wisconsin, ed. Matthew L. Figi (Green County Historical Society, 2006), supplemented by some discussion with Matt. Thanks also to the staff of the Monroe Public Library.

For better versions of the picture at the top of this entry and the frontal view further down, along with other high-quality images, go to the historical page of the Goetz Theatres site. A chronology of the Goetz Theatres is on this page, and some shots inside the booths at the Goetz 2 and 3 are here.

P.S. 15 December: Thanks again to Matt Figli, who spotted some inaccuracies in my account of Monroe’s history. They have been corrected.

P.P.S. 28 December: Katjusa Cisar’s story in The Monroe Times today brings us more information on the Goetz, both past and present.

3 curious things in 24 hours

DB here:

Okay, that’s one. (In your dreams, Goose-Boy.) You can see more here. Thanks to Peter Becker for the tip.

Second, what to do with film now that digital has arrived:

For details go here. Thanks to Jeff Joseph for the tip.

Third, I have changed careers. Pray that your “minor infraction” doesn’t come up before my court.