The Ship of Statements sails on

Monday | February 6, 2012 open printable version

open printable version

Kristin here:

I’m glad I held off seeing Jean-Luc Godard’s Film Socialisme (2010) until I could watch it on the big screen. Last September, thanks to the UW Cinematheque I was finally able to do that. I thoroughly enjoyed it, was baffled by parts, thought I understood other parts, and wallowed in the gorgeous imagery that is late Godard. I certainly didn’t understand it well enough to blog about it and point out to the nay-sayers that just because a film is well-nigh impossible to understand doesn’t mean it’s bad. Besides, Andréa Picard has already written an intelligent and spirited defense of the film on CinemaScope where she, among other things, rightly dismisses critics’ claims that Godard is irrelevant and “out of touch with the world.”

A floating metaphor with thirteen decks

I was intrigued last month to learn that the cruise ship the Costa Concordia, which ran aground on January 13 with at least 17 people killed and many others injured, was the ship Godard had used as the setting for the first section of Film Socialisme. A number of websites pointed this out and tried to make some connection, logical or otherwise, between Godard’s choice of his setting and the fact that the ship subsequently crashed. IBTraveler noted:

On Friday, Jan. 13, the Costa Concordia cruise ship crashed into rocks off Italy’s west coast. Just three days earlier on Jan. 10, Jean Luc Goddard’s [sic] hotly debated 2010 “Film Socialisme” was released on DVD. What do the two seemingly unrelated events have in common? The first of the film’s three movements, “Des choses comme ça” (“Such things”), was shot on and prominently featured the doomed ship.

The purely coincidental fact that the DVD had just come out proved mildly newsworthy and undoubtedly garnered Godard a little extra publicity.

The Guardian, in a widely quoted editorial posted two days after the disaster, described Godard’s use of the ship:

Anyone who sat through Film Socialisme may have suspected that the Costa Concordia was heading for trouble. The cruise liner was the setting for the first ‘movement’ of Jean-Luc Godard‘s ambitious, infuriating 2010 picture, serving as a self-conscious metaphor for western capital ploughing through choppy waters. In Godard’s film, the Concordia plays the role of a decadent limbo where the tourists drift listlessly amid the ritzy interiors.

The ship of state is a well-worn metaphor, but critics assumed that Godard had taken it one step further, using the multi-lingual, multi-national group of tourists singled out from among the thousands on the ship as an image of the new Europe and its growing problems. The first movement of the film ends with the title, “QUO VADIS EUROPA.”

Yet Godard did not choose the Costa Concordia and turn it into his central “self-conscious” metaphor. The ship’s makers had created it as a giant floating metaphor well before Godard shot aboard it. The Carnival Corporation ordered it in 2004 and received it in 2006. The ship and its five sister ships are operated by the Costa Crociere company in Italy, which is owned by the Carnival Corporation, also the parent company of Carnival Cruise Lines. According to the owners, the “Concordia” fleet’s name “expresses the wish for continuing harmony, unity and peace between European nations.”

Presumably as a way of expressing that wish, the Costa Concordia, the first of the ships in the fleet to be built, was designed with thirteen decks, each named for a European nation (using the Italian version of each name, since that is where the vessel is registered): Deck 1, Olanda; Deck 2, Svezia; Deck 3, Belgio; Deck 4, Grecia; Deck 5, Italia; Deck 6, Gran Bretagna; Deck 6, Irlanda; Deck 8, Portogallo; Deck 9, Francia; Deck 10, Germania; Deck 11, Spagna; Deck 12, Austria; and Deck 13 (sometimes referred to as 14), Polonia.

An ordinary director, stumbling upon such a perfect ready-made setting encapsulating one main theme of the film, would use these country names. There must be a directory somewhere, or name plates inside and outside the elevators. Yet despite all Godard’s stairway and elevator shots, he never includes a sign that would reveal these names to us. I learned about them not from the film but from the helpful Wikipedia entry on the ship. The only time in the film where I spotted a sign related to the country names was the “Salone Londra” in the background of one shot, presumably on Deck 6. The ship owners might have been heavy-handed, but Godard is not. Even the most unsympathetic critics were able to spot this central metaphor without his having to nudge them.

A floating Tower of Babel

Some commentators implied that in making his film about tourist behavior abroad the ship, Godard had somehow foretold that the Costa Concordia was doomed. The Guardian passage quoted above says a viewing of the film would tell one that the ship “was heading for trouble.” Such a statement spices up a journalistic comment, but I’m sure Godard never dreamed that the Costa Concordia would end up where it has. Certainly many, many other cruise ships are continuing to operate around the world, many of them with the same sorts of multiple restaurants, swimming pools, casinos, bars, and exercise classes that we see in Film Socialisme, and they don’t run aground and cause fatalities. The proportion of people who drive cars and are killed or injured is vastly higher than those who take cruises (or airplanes) and suffer the same fate. When a younger Godard critiqued European society in Weekend (1967), he chose a vast car crash to symbolize it.

All this in itself would not be reason to blog about the link between Godard’s film and the ship’s disaster. Yet recently Newsweek ran an intriguing editorial (also online on the magazine’s sister publication, The Daily Beast) about some possible underlying causes for the disaster, causes related to multiple languages and incomprehensible safety lectures. According to author Eve Conant:

Former crew of numerous other lines say workers were often too exhausted to pay attention during safety-training sessions, and many didn’t speak enough English to even understand what was being said. Reshma Harilal says that during her eight years as a stateroom attendant with Carnival Cruise Lines, parent company of the ill-fated Concordia, boat-safety drills varied in regularity, and she never once had a native English speaker conduct training. “We all got safety training, but even I had difficulty understanding the English of the officers who trained us, who were always Italian with strong accents.” Carnival referred questions to the Cruise Lines International Association, which responded that “training must be conducted in a language that will be understood by the particular crew members.”

[…]

Those who’ve spent their lives in the industry say some answers are floating right on the surface. One is crew-to-passenger ratios, which have widened over the past few decades from an average of one crew member for every two passengers to one for every three, according to the International Transport Workers’ Federation. Crew members work 12-to-14-hour days, seven days a week, for months at a stretch, with minimal time off. “Half the ship is working in a state of fatigue,” says James Walker, a former cruise-industry lawyer who now represents aggrieved crew. “All types of safety studies have shown if you’re really exhausted you can be impaired to the point of intoxication.” The mostly Asian crew of the Costa Concordia had been on an eight-month shift when the ship capsized after running ashore off the Tuscan island of Giglio. Accommodations were like the Titanic’s steerage section. Only managers had shared cabins, and the others slept in dormitory bunks.

This description recalled something that struck me upon seeing Film Socialisme for the first time. It was obvious that Godard was depicting the decadence, wastefulness, and conformism of the people well off enough to take such cruises. But if the film is a microcosm of the European Union, it presents that society as having seen the development a social divide between the prosperous Europeans and a new working class who have come from outside the continent, primarily from Africa, southeast Asia, and the Pacific Rim. They face not only the traditional problems of the working class but also racism and language barriers.

Godard doesn’t make this point overtly. There are relatively few shots of the ship’s crew members. The five frames below are from the only images that focus on crew members, but it’s notable that none is a sailor. Most are waiters; one is a maid. They are the ones most likely to come in direct contact with the passengers and have to obey orders from them. We don’t see anyone order them about in a peremptory fashion or scold them. Usually they are just going about their business, and almost none of them ever speaks. There’s a cook who I suspect is the man invariably present at cruise and hotel buffets making omelets fresh to order. There’s a maid dusting a room, and the inevitable waiters in the bars. The last one, with the yellow vest, is the one who speaks, saying something as she presents the bill.

These shots are so understated and appear so seldom that it is easy to overlook them. Still, their presence can’t be arbitrary. I may have noticed this motif because, even though I’ve never traveled on a huge ship like the Costa Concordia, I’ve been on enough much smaller Nile cruise ships and in enough hotels in Egypt to have seen how some European and American tourists treat the bartenders, waiters, and maids. These servant figures have, I think, an important link to the baffling use of language and the “Navajo” subtitles.

These subtitles baffled a lot of critics. Samuel Bréan has written a fascinating essay about them (and is at work on a book on translation and subtitling in Godard’s films) on senses of cinema. He points out that characters at various points speak Latin, Russian, German, Italian, Spanish, Hebrew, Arabic, Bambara, English, and Greek. In a seemingly perverse, arbitrary gesture, Godard chose not to subtitle these stretches of dialogue in any way that could render them intelligible to someone who doesn’t understand the respective languages of the characters. Rather, he included what he termed “Navajo” subtitles, small series of words that don’t add up to even the barest summary of what the characters are saying. At times they seem almost random. The film was distributed in France without these subtitles, though the French DVD lists “Navajo” in the little box concerning subtitles on the back of the box. The default setting is for them to play, though the viewer has the option to switch them off.

Some critics have assumed that the term “Navajo” refers to real American Indians and thus is in some way offensive. But as Bréan points out, a newspaper story published shortly before the film was shown at Cannes declared that the subtitles would be “as in old Westerns where the Native Americans spoke in choppy phrases.” Not real Navajo, but Hollywood’s clichéd version.

Bréan finds patterns in the subtitles: they are all written as one line, mostly with two or three words, but occasionally with as few as one and as many as five. The words have wide spaces between them, with no punctuation. The verbs are seldom conjugated; there are few pronouns or articles; and separate words are often mashed together, as with “civilwar.”

As Bréan points out, some critics found the subtitles poetic or experimental. He thinks “that if Godard took the principle of reduction inherent to subtitling to an extreme (and added other peculiarities of his own), it is, among other things, to show how relative it is to try and assess a film without acknowledging the inevitable changes in perception caused by subtitling.”

True, no doubt, and yet there is something more going on. Some of the brief strings of words are actual translations of some of the words spoken by the characters. Others are mistakes. In the opening, when the young man with the camera says “une chose,” the subtitle renders it as “nochoice,” as if some invisible non-French-speaker has heard the phrase as something like “unchoice.”

During the introduction of one of the significant characters, Mr. Goldberg, the subtitles render his name as if it were a phrase:

Even when the words are accurate, they tell so little that they actually become a distraction in the struggle to interpret what little one can from the characters’ dialogue.

Given Godard’s concern with the situation in the Arab world, and in particular the injustices done to Palestine, it is telling that the one character whose dialogue is not given any subtitling is a woman speaking Arabic.

Overall my impression of the subtitles on first seeing the film was that they place the spectator in somewhat the same position as someone who is listening to a language he or she does not really understand. When I hear someone speaking Italian or German, I can pick out individual words (no doubt being mistaken about some of them), but they don’t add up to an understanding of what is said. Whether or not we make the connection, we are in somewhat the same situation as those waiters and maids, though for them their jobs may depend upon figuring out what all these tourists speaking their various languages want from them. Europe is full of such people. We more privileged, educated people can have little sense of how they cope, but for me, Godard has found a way to sort of put us in their positions for a little while.

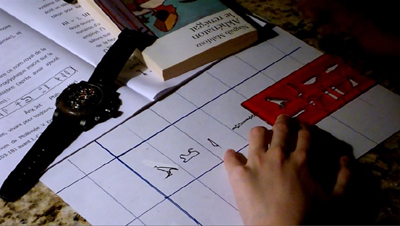

Apart from making this serious point, the focus on language also occasionally creates humor. One character lies on her bed watching a well-known YouTube video of two cats “conversing” in what sounds remarkably like human speech. The woman, however, starts meowing and declares, correctly, that the ancient Egyptian word for cat was Meow (or Miu, as the conventional transliteration of the hieroglyphs has it). She is probably the same person seen earlier writing her name, Alissa, in hieroglyphs, with an elementary introduction to hieroglyphs and a copy of Nagib Mafouz’s novel about the pharaoh Akhenaten. She is the only character presented as having enough interest in the countries where the ship will dock to study them in advance, if only superficially.

A world unto itself

Not that Alissa will get much chance to use her knowledge while ashore in Egypt. Godard does not show the brief excursions that the passengers will be taken on at the various ports of call. There is one single shot of them out on deck looking at a nearby city.

It would be doubly ironic if this city were on the Isola del Giglio, where the Costa Concordia met its fate, but that doesn’t seem to be the case. I don’t know what city this is, but it has managed to draw at least some of the passengers out onto the deck. Otherwise most of them don’t even venture outside to contemplate the sea. Most of the deck shots show immense stretches, empty apart from a few people, including a young man with a camera, and a contemplative young woman (seen in a knit cap in the “nochoice” frame above) who seems to be the closest thing we get to a point-of-view figure.

What Godard doesn’t show is that the occasional excursions are likely to be superficial. I remember on one occasion I was on a tour of Egypt. The group I was with, most of whom knew quite a bit about ancient Egypt, was spending most of the day on the Giza Plateau, hiking around the Great Pyramids and visiting the Sphinx but also viewing some of the quarries, subsidiary pyramids, ruined temples, and private tombs that cover the plateau around and between the pyramids. We went back to our bus to have lunch. While we were there, we were treated to the spectacle of 24 identical buses arriving and disgorging their full loads of tourists. Clearly they had come from one of these giant cruise ships. (Tours within Egypt seldom require more than one bus.) They had a look at the pyramids from the parking lot and walked down the hill to see the Sphinx. Reloading the buses took a while, and the entire group departed twenty minutes after they arrived. They might have gone to the Egyptian Museum, though the ticket and security lines might take too long for such a large group. Maybe they just had lunch instead and headed back for Alexandria, where their ship was docked.

The drive from Alexandria to Giza is about three hours each way, during which passengers are treated to a desert landscape empty apart from billboards for Pepsi, Coke, KFC, and other familiar products, as shown in this photo I took in 1995. (For a charming, illustrated account written by an upbeat couple who took what seems like an pretty good version of such a whirlwind tour in Egypt, see here and here. They did get a quick look-in at the museum and had lunch at the wonderful Mena House at the foot of the Giza Plateau.)

I assume the same sort of thing happens at each stop along the cruise-ship’s itinerary.

Godard’s point, presumably, is that for the vast majority of the people on the trip, the entertainment and sustenance offered within the Costa Concordia itself, along with the duty-free shops ashore (we see some of the passengers visit a gallery displaying remarkably bland art unrelated to the local culture) are the main attractions. A chance to get a photograph taken in front of the Sphinx or the Parthenon is a little bonus.

If you don’t understand Godard

Then there is the visual side of things. How could anyone dismiss a film that has images like these?