Carry me back to the old Virginia

Monday | April 30, 2012 open printable version

open printable version

Chaz Ebert and Roger Ebert on the stage of the Virginia Theatre, Ebertfest 2012. Photo by DB.

DB here:

The fourteenth Ebertfest, held in the sumptuous Virginia Theatre in Urbana, had its customary mix of independent films old and new, Hollywood classics (sometimes cult classics), an Alloy Orchestra performance, and some unclassifiable items. It was, as ever, a crowd-pleasing jamboree. It reflected Roger’s eclectic tastes and was brought to us by Chaz Ebert, festival director Nate Kohn, and woman-who-knows-and-does-all-things Mary Susan Britt.

You can see the intros, the panels, and the Q & As—that is, nearly everything, except the movies and the offside fun–on the Festival channel here.

The young and the restless

Kinyarwanda.

First features are a hallmark of Ebertfest, and many have stayed in my memory, among them The Stone Reader (2003), Tarnation (2004), Man Push Cart (2006), The Band’s Visit (2008), and Frozen River (2009). This year there were several feature debuts.

Patang (The Kite) concentrates on a single day in the life of a family celebrating the annual festival of kite-flying in Ahmedabad, India. An uncle has returned to town with his daughter, and usual in such movie reunions, old tensions are reignited. A side-story concerns Bobby, a street-wise local, and a little boy who delivers kites. Needless to say, this story intersects with and sheds light on the primary family conflict.

Prashant Barghava is a pictorialist with an eye for startling color and compositions. Shot in nervous handheld images, with many planes of action jammed together and the camera eye seeking something to focus on, Patang reminded me of The Hurt Locker, but without that film’s sense of ominous vigilance. The tone of this one is more exuberant, and the cast of nonactors gives it vibrancy.

Kinyarwanda, by Alrick Brown and an energetic team of collaborators, explores the Rwandan genocide of 1994 in an unusual way. It displays the role of the Muslim community in protecting the Hutu population (many Christian, some not) from the depredations of the Tutsi death squads. To emphasize the breadth of experience, the film adopts a chaptered network-narrative structure. A Catholic priest, a young woman, an angry Tutsi, a sympathetic imam, a little boy, and a leader of the Rwanda Patriotic Front gradually converge, first in a mosque compound, and ten years later in a reeducation and reconciliation camp. The film also plays with time, replaying some key events—notably the Tutsi’s advance on Jeanne’s home—but also anticipating some outcomes. Interestingly, by showing many of the Tutsi killers in 2004 repenting their crimes before we see those attacks, the film builds a degree of compassion into its overall form.

Scenes with adults are dominated by either personal problems (the Hutu/ Tutsi clash infiltrates a marriage) or discussions of religious doctrine. There are as well wordless moments in which we follow children—a little girl whose Qu’ran has been defaced, a boy who encounters a death squad while sent to fetch cigarettes. If the adults supply the film’s prose, the kids are its poetry.

Patang played both Berlin and Tribeca and will be opening in New York, Chicago, and San Francisco soon. Kinyarwanda won awards at several festivals, including Sundance and AFI Fest, and is coming to several other festivals. It arrives on DVD 1 May.

The misfit section

Terri.

Two other young directors got good exposure. Robert Siegel wrote the screenplay for The Wrestler after working on The Onion (Madison cheer obligatory here). His debut feature, Big Fan, is the story of a football fan who is mangled by his idol and has to struggle against his family’s pressure to sue. Patton Oswalt, who had to cancel his Ebertfest visit at the last minute, played Paul with a potato-like obstinacy that offset the shrieking caricatures around him. On the down side, I could have done with a couple of hundred fewer close-ups. (Watching a movie at the Virginia reminds you of the power of the two-shot.) Still, Siegel wisely doesn’t give his hero a girlfriend who would lead him to the Big Normal and wean him away from his obsession. As Siegel points out, “He’s completely happy, but everyone around him thinks he’s unhappy.” Big Fan is an enjoyable portrait of the sports nerd.

More laid-back was Azazel Jacobs’ second feature Terri. It’s sort of a coming-of-age movie, but it has a peculiar humor that such wistful exercises usually lack. Terri, an enormous teenager, goes to high school in pajamas and is teased mercilessly, but he reacts with a dead-eyed passivity that suggests both resignation and resilience. Like the hero of Gulliver’s Travels, the book Terri is working his way through, he’s tied down by Lilliputians around him, but he gets by.

It’s a film of character revelation rather than plot turns. No, Terri’s addled uncle isn’t going to die; no, Terri’s not going to lose his virginity. The action revolves around Jacob Wysocki as the title character and John C. Reilly, who never disappoints in any film, as the school principal. Their scenes together are the heart of the film, and if Terri is looking for a father-figure/ role model this off-center administrator with a soft heart for hard cases wouldn’t be a bad choice. To the film’s credit, though, we have little reason to suggest that he’s looking for any such thing. This movie has tact.

I ran into another Ebertfest first-time-director, Nina Paley, whose Sita Sings the Blues (2009) I first saw and loved at Roger’s event. Kristin had already seen it at the Wisconsin Film Fest. Sita worked her way into our blog and into our Film Art material. Nina, long a foe of copyright in any form, told me she plans an act of “copyright civil disobedience” soon. In the meantime, check her effervescent blog site, news of her new project Seder-Masochist, and excerpts from her new books about Mimi, Eunice, and their take on IP.

And then there was…

Take Shelter.

The first evening’s late show was given over to John Davies and Raymond Lambert’s Phunny Business, a documentary about the rise of a Chicago comic club, and this was preceded by Kelechi Ezie’s The Truth about Beauty and Blogs. I had to miss the doc, but go here for a review from Scott Jordan Harris. The short was charming—a snappy comedy about a single woman trying to be Queen of All Media on her YouTube show. Very quickly her aplomb cracks and she uses her online persona to recapture her straying boyfriend. Her web skills give her a rostrum, and then a tracking device (she follows him on Facebook), but soon her site turns into a diary of mounting desperation.

Higher Ground: Not a come-to-Jesus moment but a go-from-Jesus one. I had trouble figuring out the tone. I think the obvious caricatures, including an unctuous evangelical marriage counselor, were there to suggest that the ordinary believers were more worthy of respect. But they all gave me the creeps, including the relentlessly sunny pastor. Also, it seemed a bit of a hothouse drama. I missed a sense of exactly where this story took place, and I kept wondering how all these people made a living wage. But of course it’s Vera Farmiga’s film, and as usual she projects a wary intelligence. The opening sequence showing a string of people being immersion-baptized had a winning radiance.

Joe vs. the Volcano: Joe wins the match, sort of. It deserves to be a cult film for its portrayal of a workday out of the dankest basements of Brazil and Hudsucker Industries. Still, I thought everybody was trying a little too hard, especially Meg Ryan. Cinematographer Stephen Goldblatt talked about how he likes shooting on film and showing on digital: Film’s richness can support 4K, 8K, or whatever. As for 48 frames per second: “I can’t wait.”

Paul Cox: On Borrowed Time: A warts-and-all tribute to the stubborn director of over thirty films. I can’t think of a question to ask about Paul Cox that the film doesn’t answer.

The Alloy Orchestra: Wild and Weird: Classic early trick-films plus a couple of avant-garde items from the 1920s given new brio by the Alloy boys. It was fun but less hefty than earlier efforts. I especially liked re-seeing Winsor McKay’s Dream of a Rarebit Fiend (aka The Pet) from 1921, which replays McKay’s fascination with figures and spaces that swell to mammoth proportions (a bit like Avery’s King-Size Canary), though the effect is less looming onscreen than in the comics. You can see the whole thing, and other of the W & W titles, on Fandor, one of this years E-fest sponsors.

I’d like to see the Alloy talents and others move away from the big spectacles like Napoleon and Metropolis, which appeal to our current tastes in splashy films with special effects, and toward quieter, less-known silent masterworks by the French (e.g., Germinal), the Danes (The Abyss, The Ballet Dancer, The Evangelist’s Life), Italians (Il Fauno, Rapsodia Satanica, Ma l’amore mio non muore) and above all Victor Sjöström. Audiences would, I think, love Ingeborg Holm, Sons of Ingmar, Masterman, and The Girl from Stormycroft, and the Alloyists could do them proud. Not to mention William S. Hart, whose films are among the pride of US silent cinema.

Take Shelter: A tour de force of what literary theorists call the fantastic: Is the hero going mad, or is there indeed something real behind his visions of impending disaster? Everyone has praised, and rightly, the precision of the performances and framings. Jeff Nichols was another first-timer at Ebertfest some years back, with Shotgun Stories. Take Shelter is the sort of movie that makes independent American cinema proud.

A Separation: I wrote about it here a year ago, having seen it during what might be my last visit to Hong Kong. This time around, I admired it all over again. It shows many characters’ attitudes without bias (everyone has his or her reasons), and it’s aware of how lies told out of loyalty corrode love. The screening was enhanced by excellent background information from Michael Barker of Sony Pictures Classics and Omer Mazaffar during the Q and A.

If you’re a good storyteller, I think, you balance straightforward presentation (e.g., A Separation’s exposition, which sketches in the core of a relationship) and somewhat sneaky suppression (e.g., the ellipsis that hides a key event from us). I’ve argued that Iranian directors understand suspense better than almost anybody working today, and this film supports that hunch. Now let’s get hope we get to see, on some platform, Arghadi’s earlier exercise in mystery and ambivalent morality, About Elly. Now there’s an overlooked/ forgotten film.

E-fest goes digital

Ebertfest has shown digital copies of films in the past, notably Bad Santa and Woodstock, but this time around only Take Shelter was on film. Everything else was on HDCam, except Paul Cox: On Borrowed Time, which was on Blu-ray.

James Bond, legendary projection magician and theatre designer/ outfitter, oversaw the shows. Although the films often looked very good on the 50+ -foot Virginia screen, his expert eye saw shortcomings in the digital versions. Even I could detect the videoish quality of Joe vs. the Volcano. It looked pretty good, but compared to what James had shown in years past—70mm prints of Lawrence of Arabia, Play Time, My Fair Lady—there was definitely a sense that we were passing into a new era. Above you see James between his thoroughbreds, the lovingly assembled 35/70mm projectors.

Because Steak ‘n Shake became a festival sponsor this year, Roger presented James with the first-ever S-n-S award, a cap displaying the motto, “In Sight It Must Be Right,” a fitting label for James’ superlative standards in projection. Here he receives the Order of Takhomasak.

James was ably assisted by Steve Kraus and Travis Bird, who is both a musician and a cinephile. Great guys and great professionals, all.

The Virginia Theatre, an analog artifact if there ever was one, is closing after Ebertfest this year. It will be renovated and spiffed up, with new seats and many other upgrades.

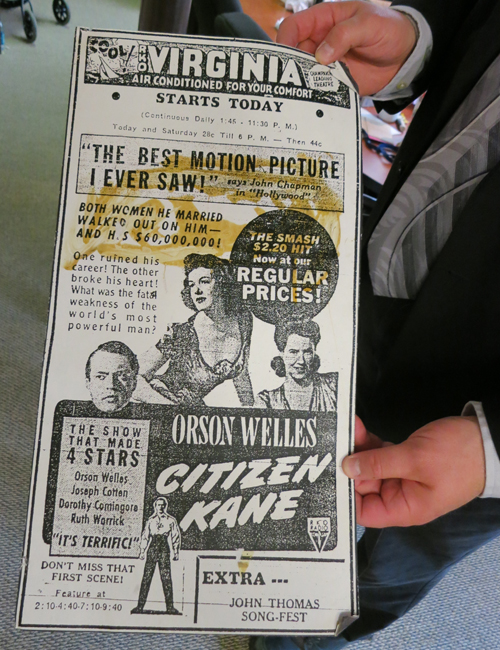

The festival wrapped up with Citizen Kane brought to us digitally. A Blu-ray copy was screened, and instead of the film’s original track, we heard Roger’s pointed and wide-ranging 2001 commentary. He was by this point an old hand at play-by-play explication, after years with his “Cinema Interruptus” series, now taken over by Jim Emerson. After the screening, I was happy to be able to interview Jeff Lerner, of Blue Collar Productions. Jeff produced and recorded Roger’s commentary. Again, check the Ebertfest channel if you want to see the Q & A, which takes off after Chaz’s moving memoir.

Thanks to the many staff and guests who made this year’s Ebertfest especially enjoyable. I’m particularly grateful to C. O. “Doc” Erickson for giving me an interview for an upcoming blog entry, and to David Poland and Michael Barker for enlightening table talk. Thanks as well to Jim Emerson, excellent companion of the highway.

Thanks to Kat Spring and Nate Kohn for correction of boo-boos.

Speaking of digital, here’s a neat possibility: http://gizmodo.com/5906353/the-avengers-screening-delayed-because-some-dunce-deleted-the-freaking-movie.

This deserves a blog entry of its own. The hands belong to Steven Bentz, Virginia Theatre Director, whom we must thank for preserving this ad (from, I assume, 1941). Note the listing of start times for the feature, and the request not to miss the opening. This is a topic discussed elsewhere on this site.