Archive for September 2012

DIAL M FOR MURDER: Hitchcock frets not at his narrow room

Dial M for Murder (1954).

DB here:

This cut makes you say: Huh? Margo’s hand is shamelessly out of proportion and, judging by the men’s stares, we’re somehow looking through her torso.

Yet does anybody notice it? The cut reminds us that Hitchcock can get away with murder, cinematically speaking. Probably you didn’t need reminding, but even an inveterate Hitchcock watcher (I saw Dial M for Murder when I was about seven years old) can still be shocked by the old guy’s sheer bravado.

In 1979, Dial M was revived, and a restored version began a tour as a re-release, playing in 3D around the US and Europe. It ran in New York’s 8th Street Playhouse in 1981, and Kristin and I caught it in London at about that time. Most relevant to today’s entry, in September of 1981, it screened in a 3D retrospective at what was then called the Festival of Festivals, the earlier incarnation of the Toronto International Film Festival. According to Variety, the late-night show turned away a thousand people.

It’s good to report, then, that about thirty years later it returns to what has become one of the most important festivals in the world. Last night Dial M, muscled up in a digital restoration, screened to a sold-out house at TIFF. Preparing some remarks to introduce it, I found myself captivated once again by this curious project. Overshadowed by Rear Window, which was released later the same year, it now seems quite a daring movie, and not just because of this brazen cut. This newest restoration is very welcome, for it gives us an occasion to see what Sir Alfred can sneak past us.

Naturally, there are spoilers ahead, so if you haven’t seen the film you probably shouldn’t read past the next couple of sections.

3D: Device, demand, decline

During the 3D boom of early 1953, Warner Bros. was an enthusiastic participant. House of Wax, released in April, had proven a huge success; ultimately it would earn $9.5 million and become the top 3D release of the period. Jack Warner halted production from April through early July in order to retool the studio for the new process. Jack announced several pictures going into stereoscopic production, including Lucky Me, Helen of Troy, Them, and A Star Is Born. None of these wound up in the new format, but two others, Hondo and Dial M for Murder, did.

At summer’s end, 3D was starting to flag, largely, it seems, because screening the films posed so many problems. No system had been standardized, and different studios embraced various formats. Late in 1953, some interest perked up, chiefly because of Hondo and MGM’s Kiss Me Kate, but very soon the fad was over. In early 1954 most 3D releases played in their flat forms, and some were released only that way. In April, a month before Dial M opened, Variety ran a story headlined “3-D Looks Dead In United States.”

Dial M had been shot in summer of 1953. According to Bill Krohn, Warners was obliged by contract to wait until the original play had concluded its run, so the release was delayed until May 1954. By then even Jack had lost faith in the format. Dial M was the first Warners 3D picture that the studio permitted to be shown flat in first run, and most exhibitors took that option. 3D, Hitchcock reflected, was a nine-day wonder, “and I came in on the ninth day.” The picture still did reasonably well, earning $3.5 million–but Rear Window returned nearly three times that to Hitchcock’s new home, Paramount.

Wider, deeper, in color

Dial M for Murder confronted Hitchcock with three new technical challenges. Most obviously, the demand that the film be shot in 3D created problems with the bulky camera (“the size of a room,” Grace Kelly remembered, with some exaggeration). It couldn’t focus some shots as closely as Hitchcock would have preferred. The extreme close-up of Tony Wendice dialing, like the shot that starts the opening credits, had to be made with a giant telephone and a big fake finger, a piece of effects work that Hitchcock happily publicized.

Dial M for Murder confronted Hitchcock with three new technical challenges. Most obviously, the demand that the film be shot in 3D created problems with the bulky camera (“the size of a room,” Grace Kelly remembered, with some exaggeration). It couldn’t focus some shots as closely as Hitchcock would have preferred. The extreme close-up of Tony Wendice dialing, like the shot that starts the opening credits, had to be made with a giant telephone and a big fake finger, a piece of effects work that Hitchcock happily publicized.

Moreover, cinematographers were still figuring out how to judge each shot’s best convergence point (roughly, the way the two lenses defined the location of the screen’s surface) and interocular distance (the distance between the two lenses, mimicking the spacing of our eyes). Misjudging these factors could lead to distortions, such as making actors look closer together or farther apart than intended. Hitchcock worried about the “waste space” around his players in the initial footage the crew shot. In addition, directors had to be careful when the convergence point was set beyond foreground figures. If the figure was cut off by the frameline, a partial torso could be floating out at the audience. (The same threat can arise in today’s 3D films.) Interestingly, there are very few shots in the film’s first half that use a vertical frameline to bisect a character, and almost no over-the-shoulder reverse angles, which were, according to one cinematographer, risky.

Hitchcock’s concern for too much empty space might have been aggravated by the studio’s demand that the film be in widescreen. With the rise of CinemaScope, most studios had decided to release films in wide formats, and Warners was no exception. Dial M was released in 1.85:1.

Finally, although Hitchcock had shot in color before, this was his first outing with Eastman Color, a single-strip emulsion that eliminated the need for three-strip Technicolor. (Indeed, Eastman Color made several new processes, like 3D and CinemaScope, feasible.) But the new stock was somewhat less sensitive to light than Technicolor, and one advantage of shooting single-strip—the fact that you no longer needed the big Technicolor camera—was lost because of the 3D apparatus.

Faced with these obstacles, Dial M can look like a step backward. In Hitchcock’s interview with Truffaut, he agreed, claiming to have been “coasting, playing it safe. . . . I was running for cover again.” He had been planning a more personal project that fell through, and it was Warners that suggested he do Dial M, a property they’d acquired. After seeing the play, he agreed, but even while shooting, Grace Kelly recalled, he was already planning Rear Window.

At first glance, Dial M for Murder seems like the epitome of photographed theatre. Nearly all the action unfolds in the apartment of Tony and Margot Wendice, mainly in their living room. We get brief views of the bedroom, the terrace, and the hallway outside. Only about five minutes, or about 6 %, of the film take place on the street or in Tony’s club.

Both Frederick Knott, author of the play and screenplay, and Hitchcock failed “to take full advantage of the screen’s expansive powers,” opined Brog. of Variety. “As a result, ‘Dial M’ is more of a filmed play than a motion picture.” In talking with Truffaut, Hitchcock seemed to agree. “I just did my job, using cinematic means to narrate a story taken from a stage play.” In another interview he elaborated:

I think that’s the job of any craftsman, setting the camera up and photographing people acting. That’s what I call most films today: photographs of people talking. It’s no effort to me to make a film like Dial M for Murder because there’s nothing there to do.

Actually, I think there was a lot there to do, and Hitch did it.

Acknowledging the source

We could counter Hitchcock’s just-a-job-of-work argument easily by citing what he did with the famous attempted strangulation. Swann, alias Lesgate, has slipped out from behind the curtain. After waiting tensely for Margot to lower the phone, he wraps the scarf tightly around her neck and thrusts her onto the desk. She squirms, frantically grabs a pair of scissors, and stabs him in the back. Next, according to Knott’s stage directions:

Lesgate slumps over her and then very slowly rolls over the left side of the desk, landing on his back with a strangled grunt.

No viewer will ever forget the far more hideous death that the would-be killer suffers onscreen. After flopping over Margot, apparently dead, he snaps back to life spasmodically, as if jolted by bursts of electricity. His body yanks itself erect, his arms twisting helplessly as he tries to withdraw the blades, before he turns over and hits the floor . The impact drives the scissor blades further into his back. Hitchcock celebrates the moment with an Eisensteinian overlapping cut to a close-up of the scissors. He had a special pit dug, he proudly told a reporter, to make the lens flush with the floor.

So much for just setting up the camera and photographing the people acting. We could point to other alterations from the play, such as the strained drawing-room courtesies that frame the whole story. “Let me get you another drink,” is the film’s first line, as Margot and Mark pull out of a passionate clinch. At the end, nabbed, Tony offers to pour his wife and her lover a drink, and then asks the detective: “I suppose you’re still on duty, Inspector?” There’s also the peculiar mustache motif. The play text and the film dialogue mock Lesgate/ Swann slightly for growing one, but the film adds the mini-gag of self-satisfied Inspector Hubbard calmly combing his own mustache.

Fine as these isolated moments are, Hitchcock’s treatment is more thoroughgoing. He does, as he tells us, use cinematic means “to narrate a story taken from a stage play.” But those means are unusual and instructive.

Hitchcock had already experimented with plots confined to tight quarters–a lifeboat (Lifeboat, 1944) or a parlor and hallway (Rope, 1948). It’s plausible, as many critics have noted, that he tried the same thing with Dial M. But those earlier films seem more technically radical. You couldn’t ask for a much more cramped space than a lifeboat, unless you wanted a phone booth (which Hitchcock did consider for a film). Similarly, Rope‘s experiment with very long takes (it has only 11 shots) made it extraordinary for its day. From this perspective, Dial M can look like a retreat. It expands its range of action in modest ways, and it doesn’t try for a consistent long-take look. There are nearly seven hundred shots, and the average runs a little under ten seconds, quite normal for the period.

Yet limiting the action largely to the apartment wasn’t exactly taking the line of least resistance. In adapting a play, there’s always a temptation to open things up. Most plays include a great deal of action that takes place before the play’s opening scene, or in other locales offstage. In other words, the plot of the piece is highly selective and concentrated in both space and time, while the broader story—the sum of all the incidents that contribute to the action—is recounted or suggested on stage. Most film adaptations “ventilate” the original by dramatizing these scenes, as Brog. apparently would have preferred.

Hitchcock resisted the temptation to open out the play. Showing scenes that take place before the stage action (perhaps the theft of Margot’s handbag, or Tony’s stalking of the shady Swann/ Lesgate) would have lost the tight focus of the original. Moreover, we can gain an extra layer of interest when action is recounted rather than dramatized: we get both past events and present attitudes toward them. (In other words, sometimes we should tell rather than show.) Most intriguing, though, is Hitchcock’s comment to Truffaut that opening up a play “overlooks the fact that the basic quality of any play is precisely its confinement within the proscenium.” Hitchcock wanted “to emphasize the theatrical aspects.”

Hitchcock wasn’t alone. In the 1940s, several filmmakers were rethinking the problem of filming theatre, and they were exploring ways to bring out the “theatrical aspects” of the material. In a brilliant 1951 essay, André Bazin pointed out that filmmakers were now confident enough in their creative choices to adapt plays while acknowledging the pleasure of purely theatrical conventions. These films, he suggests, engage us by acknowledging the theatricality of theatre.

Bazin pointed to Olivier’s Henry V (1944), which begins in an Elizabethan playhouse and gradually moves its scenes to realistic settings. He mentioned as well Cocteau’s Les Parents terribles (1948), which, somewhat in the manner of Dial M, finds an equivalent for the play’s single-room set by expanding the film’s locale just slightly to take in an entire apartment. Other examples would include Welles’ Macbeth (1948), Melville’s Les Enfants Terribles (1950), and H. C. Potter’s The Time of Your Life (1948). Earlier in the decade, the obviously artificial sets and to-camera addresses of Our Town (1940) and Wyler’s handling of the parlor and staircase in The Little Foxes (1941) suggest a sort of para-theatre, cinema that supplements or amplifies stage conventions rather than trying to escape them.

That Hitchcock should join this trend toward new forms of filmed theatre is surprising. Earlier in his career, as a director nurtured by the silent movies and particularly American and German films, he had been an advocate of “pure cinema.” That meant, above all, editing and pictorial storytelling. Talky scenes were anathema. He wrote in 1937:

If I have to shoot a long scene continuously I always feel I am losing grip on it, from a cinematic point of view. . . . What I like to do always is to photograph just the little bits of a scene that I really need for building up a visual sequence. I want to put my film together on the screen, not simply to photograph something that has been put together already in the form of a long piece of stage acting.

Yet in 1948, he explained that he had yearned to film scenes in long takes.

Until Rope came along, I had been unable to give full rein to my notion that a camera could photograph one complete reel at a time, gobbling up 11 pages of dialogue on each shot, devouring action like a giant steam shovel. As I see it, there’s nothing like a continuous action to sustain the mood of actors, particularly in a suspense story.

He took much the same approach in Under Capricorn (1949).

Why does the montage-oriented director ten years later make two of the showiest long-take films in Hollywood history? I’ve suggested in an essay in Poetics of Cinema that there was something of a long-take contest among American directors in the decade after Citizen Kane. The competition was propelled partly by new equipment that permitted long, flowing camera movements. This “fluid camera” trend, as it was called in American Cinematographer, pushed ambitious directors toward shots that might run several minutes. Welles, Preminger, Minnelli, Cukor, Ophuls, Siodmak, Joseph H. Lewis, and several other directors tried their hands at virtuoso long takes, and in some cases those were applied to stage adaptations. Welles stretched one shot in Macbeth to the length of a whole camera reel.

With Dial M, Hitchcock largely gave up the long take (though a few shots run a minute or so), but he tried something else. He offered a form of filmed theatre that has its roots in silent moviemaking, and he explored ways to transpose it to 3D cinema.

A chamber play

Sylvester (1924).

In fall of 1924 Hitchcock went to Germany, where he toured the magnificent Ufa facility and became acquainted with the work of the industry’s outstanding creators, especially Lang and Murnau. Most writers have emphasized his acquaintance with the Expressionist films of the early 1920s, and he sometimes mentioned his admiration for The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari. But he also praised Lubitsch, who was no Expressionist, and when asked about his major influences, he answered, “The Germans. The Germans.” It’s not farfetched to assume he was aware of another trend in local production, the one known as Kammerspiel.

The Kammerspiel, or “chamber play,” emerged in German theatre, and the film equivalents appeared in the early 1920s. The Kammerspiel film typically confined itself to a few settings and emphasized psychological conflicts among a small cast of characters. Surprisingly, the major instances, such as Shattered (Scherben, 1921), Backstairs (Hintertreppe, 1921), and Sylvester (aka New Year’s Eve, 1924), weren’t adapted from plays but were original scripts by Carl Mayer. The most famous Kammerspiel film, which Hitchcock would likely have seen during his visit, was Der letze mann (aka The Last Laugh, released December 1924), directed by F. W. Murnau. Extensive tracking shots were rare in most silent movies, but Murnau built his film around them. He and Mayer, who had scripted Der letzte Mann, came to America and there made Sunrise (1927), famous for its elaborate camera movements.

Another major director pursued the chamber aesthetic well beyond the silent cinema. Carl Dreyer had made a Kammerspiel film, Michael (released September 1924), and he carried the lesson of the trend back to his native Denmark with The Master of the House (1925), an adaptation of a popular play. Like Dial M, the film concentrates on one locale—a family’s apartment, built out of hundreds of detailed shots of the actors and sets, with almost no camera movements. Later, Dreyer would apply the Kammerspiel aesthetic to other play adaptations, Ordet (1955) and Gertrud (1964), but presented in long, gradually unfolding tracking shots.

With a Kammerspiel aesthetic, you get something fairly distinct from what we think of as filmed theatre. The baseline prototype of filmed theatre is the PBS/ Metropolitan Opera model: a live performance captured by several cameras. The cameras don’t really penetrate the space; they give us different angles and shot scales (usually thanks to different lens lengths), but we don’t have a sense that the camera is in the thick of things. A more flexible form of filmed theatre occasionally inserts the camera among the performers, as with certain shots of Wenders’ Pina. But for Hitchcock, Dreyer, and the chamber-film aesthetic, the space of the “stage” becomes completely permeable. The actors are stuck in the set, but the camera can go anywhere there. The camera can scan the space, jump below or above it, even rotate. The result feels both theatrical and cinematic—a concentrated stage piece heightened by the tools of cinema.

Locked inside these four walls

Films in the Kammerspiel mode find drama in intimacy and routine. Sometimes called “doorknob cinema,” these films draw suspense out of prosaic activities: crossing a room or simply waiting for someone to come through a doorway can become major turning points. Dial M is doorknob cinema par excellence; a latch comes close to being a character. But the director’s problem is to dynamize this enclosed space, to make furniture and entryways and trips back and forth across a parlor engrossing. So it’s a question of how to film it all.

The proscenium tradition of Western theatre pretends that the setting’s fourth wall has been removed. We look through it to the action. PBS-style canned performances preserve this convention, keeping us on the auditorium side. But Kammerspiel-style filming doesn’t adhere to this. Not only does the camera shoot from angles that would be unavailable to a spectator in a playhouse, but it may show all four walls of the set. Dreyer’s Master of the House does this, freely cutting from one side of the action to another, so rigorously that we could sketch a complete floorplan of the rooms.

Dial M does much the same. Consider that bar table against one wall. It’s shown straight on in many shots, but at least once the drinks are shown in the foreground (with striking 3D saliency) and behind Margot and Mark we see the other wall behind them, the one “through which” we’ve seen action before.

Why go to the trouble of showing the fourth wall? It supplies visual variety while expanding the play in a way that is at once “theatrical” (the space is still enclosed) and “cinematic” (the camera can go anywhere). Allowing a fourth wall also permits more complex staging effects. Characters can now make a circuit around the entire set. This is notable in Dreyer’s late films, when the character’s walk is covered in a single tracking shot, as if the set’s four walls have been ironed out on the screen.

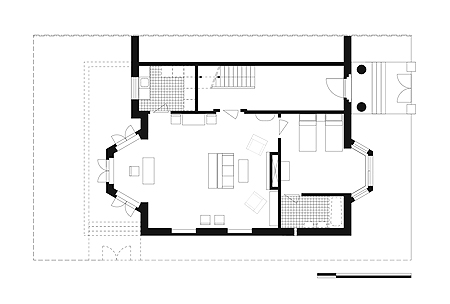

Hitchcock does the same sort of thing through cuts. In one scene, we follow Tony as he finally takes control over Swann, convincing him to kill Margot. Here the showing of the fourth wall can mark off a privileged portion of the scene. To get a sense of how this happens, we can look at a plan of the apartment provided by Steven Jacobs in his stimulating book The Wrong House.

The living room is the biggest space, with the kitchen (never shown) and hallway above it. To the right of the living room are the bathroom (never shown) and the bedroom. The street is at the far right of the diagram, the terrace and garden at the far left.

The living room is the main arena of action. In the left area are the French windows, with Tony’s desk and desk chair in the alcove. The drinks bar, flanked by two chairs, stands along the uppermost wall. Adjacent to the right chair is the crucial main doorway. In the center of the room, facing the fireplace at the right, is the sofa and coffee table, with a narrow table running behind the sofa. Two wingback armchairs are angled alongside the fireplace. On the long bottom wall are bookshelves, hanging pictures, two chairs, and a china cabinet (not pictured).

During most of the film, we are oriented to the apartment from camera positions facing the wall with the drinks bar and the doorway (the top area of the floor plan). At a crucial passage, however, Hitchcock takes us around the entire living room, clockwise.

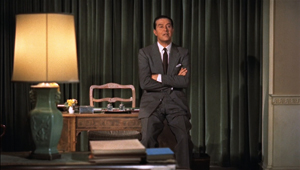

Tony has been unveiling how much he knows about Swann’s crimes. In this movie, the desk is the place of power, where both the phone and Tony’s account book are. Starting at the desk, Tony builds up the pressure. He moves along the familiar side of the room to confront Swann as he wipes the glasses.

He controls their conversation, even when he pauses to sit down and face a looming Swann.

These shots get Tony to a midway resting point. He explains that he’s already framed Swann as the man blackmailing Margot. This pushes Swann into an angry sulk. Hitchcock uses Swann’s static profile as a pivot, in order to switch camera positions 180 degrees. As Tony continues to squeeze Swann, we see a corner of the fourth wall we just more or less occupied.

Call this the “stick” part of the sequence. When Tony proposes a carrot—a thousand pounds in exchange for killing Margot—we follow him from the new side we’re on. Swann turns uneasily away, and a slight change of angle accentuates his shift.

As Swann edges to the fireplace, Tony strolls rightward, passing a bookcase and the china cabinet. When he gets to his desk, he reaches into a drawer.

“You can take this hundred pounds on account.” He tosses the money across the room, and the camera pans with it across the fourth wall. The sheaf of bills lands in the wingback chair Tony had relaxed in earlier.

Swann doesn’t touch the money but advances to the desk to check Tony’s claim that the bills can’t be traced. So we make another half-circuit of the room.

Now we’re back in the zone in which the shot started. When Tony says that the murder will take place “approximately where you’re standing now,” Hitchcock cuts to a low-angle shot of Swann, starting. (This is one of many examples gainsaying the idea that a low angle confers power on an individual.)

This entire passage, the culmination of Tony’s efforts to recruit Swann to his cause, is rendered in a series of fairly short shots, not long tracking movements. And indeed the “wild wall” with the bookcase would have been much more difficult to manage in a single take. Probably that’s one reason Rope doesn’t show us its fourth wall.

After this patient, quietly bravura passage, Hitchcock starts a new one, this time from a high angle.

The orientation, one we haven’t seen before in the film, marks a fresh phase of the action: it’s the first of many rehearsals and replays of the killing. This section of the scene gains force by its contrast with earlier low-angle shots and the steady circuit we’ve made of the living room.

Echoing frames

Naturally, Hitchcock dynamizes Knott’s play by means that we’ve seen in other of his films. There are passages of subjective cutting, in which we’re given the optical point-of-view of a character. Early in the film POV shots are assigned to Tony, but as Margot gets drawn into his trap, Hitchcock gives her subjective shots too. The pivot comes when during Hubbard’s questioning. Tony steps out from behind the Inspector and her glance flicks to check his expression. She’s telling the lie he coached her to tell. Our alliance starts to shift to her–and to Hubbard, through whose eyes we’ll see what happens in front of the house at the climax.

At the climax, when Inspector Hubbard brings Margot out of prison to solve the case, a comparable peekaboo dance takes place through her vision, with Tony replaced by Mark.

There’s also the remarkable passage of mental subjectivity reminiscent of 1940s montage sequences, in which Margot’s trial and condemnation are compressed into abstract shots showing her as if facing the judge (above). These images again at once open up the play a bit and keep faith with the tightly circumscribed premises of the film. As Hitchcock explained to Truffaut, he handled the court proceedings in such a stylized fashion because shifting the action to another concretely defined space would have destroyed what he’d built up. “People would have started to cough restlessly, thinking, ‘Now they’re starting a second picture.'” The passage also reinforces our emotional attachment to Margo that was initiated during Swann’s attack.

Keeping the action within one set also allows Hitchcock to exploit a tactic that’s common to Hollywood films but that seldom gets such a workout—the repeated setup that carries echoes of earlier actions. I’ve supplied examples in an earlier entry, on Nolan’s The Prestige, but needless to say Hitchcock gives us a master class in reiterated or rhyming setups. The several tours of the apartment activate different props and zones while also highlighting key areas, such as the desk and the door that will come back later. When you have only a few sets, you can layer the audience’s sense of the scene’s progress by calibrating your camera positions to evoke earlier shots of the same bit of space.

For example, when the police are investigating Swann’s death, a high angle ironically echoes Tony’s rehearsal of the murder plot (above). Another straightforward instance is seen in the low angle on Tony in the wingback chair. We first see it when Tony offers his purring explanation of how he’ll frame Swann (above). That shot is recalled quite precisely when, after having adjusted to Swann’s death, he relaxes in the chair after setting up the framing of Margot.

The hallway area receives more prolonged development, with the carpeted stairs becoming more prominent as the film proceeds.

In the second shot above, Hitchcock denies us what any other director would show: a closer view of Tony slipping the key under the carpet as he’s talking casually to Margot. It’s a token of respect for our intelligence, I think. He knows we’re watching Tony’s hand, even in long shot.

Not until Swann arrives do we get the variant of the framing that will be modified at the climax, when Tony comes back from the police station.

Both of these shots play out as parallels and variants, as each man reaches for the key under the stair carpet.

A similar framing presents the grisly aftermath of the murder attempt, contradicting Tony’s confident patter about the plan.

Later, the key framing shows Inspector Hubbard setting the trap for Tony, in a shot recalling the trap Tony set for Margot. When Tony is caught and tries to escape, Hitchcock cuts to the prime orientation to show his path barred.

Of course, filming several shots from the same general setups can save time during production, but shrewd directors turn those repetitions to narrative advantage. In this case, they let Hitchcock have his cake and eat it too: he can stay concentrated on a single set, but he can create a web of associations among different phases of the action. The narrow rooms of Knott’s play are transformed by cinema.

Superflat?

The widescreen format forced upon Hitchcock may have been another source of his worry about “waste space.” He used lampshades and other items of furniture to balance the 1.85 compositions. More important, his use of 3D has long seemed rather conservative. Is it?

There are almost no instances of objects popping out from the screen surface; the famous example is Margot’s hand plunged out and toward the scissors on the desk during Swann’s attack. The space is discreetly layered, as when the bottles on the bar table or the bedstead moved to the living room command the foreground of shots. On the whole, Hitchcock follows both advice and custom in using the frame as a window: the depth is on the other side of the screen, tapering toward the distance. This was recommended practice at the time, and still is today.

More important, 3D Westerns like Fort Ti and Hondo and 3D musicals like Kiss Me Kate have settings stretching into the far distance, so you can show an extreme range of depth behind the screen/window. But if you’re shooting an apartment set, you don’t have much distance to play with. The result is a “shallow depth” that is at odds with a central trend of 1940s cinema and many 3D productions of the day.

Like other directors working in the 1940s and early 1950s, Hitchcock sometimes embraced tight depth compositions with big foreground heads or objects. Here are shots from The Paradine Case (1947) and I Confess (1953).

Color filming made shots like these more difficult, as the film speed didn’t allow the lenses to be stopped down so far. Accordingly, for Rope and Under Capricorn, Hitchcock either spread his actors out clothesline-fashion or kept the foreground far enough from the lens so that the depth of field could be managed.

3D added more constraints. Fox cinematographer Charles G. Clarke recommending putting nothing very close to the camera and relying on 50mm lenses for medium shots (rather than the wider 35mm ones common in 2D black-and-white filming). Hitchcock’s cinematographer Robert Burks had shot Hondo and is said to have worked uncredited on House of Wax, so he was aware of the emerging 3D conventions. But the relatively flat spaces of Dial M yielded depth shots that don’t spread its faces across great distances. In many of the shots shown above, you can see that when figures are arrayed in some depth, the foreground is fairly far away from the lens. We have a convenient comparison in the opening of Shadow of a Doubt (1942) and a late scene in Dial M.

In the later film, Milland in the foreground is further from the lens, and Cummings is closer to him than the landlady is to Joseph Cotten. In most shots in Dial M, the space of the set is shallower, and the characters are typically packed closer together, than in the deep-focus films of the 1940s.

Paradoxically, then, it was harder to get aggressive depth compositions in 3D films than in 2D ones. But Hitchcock seems to have taken advantage of the shallow space of the Wendice apartment to concentrate on his actors, often isolated in single shots rather than the jammed frames of the 1940s. Given the wider frame, his compositions may seem bland, and sometimes they display the waste space he deplored. Still, his approach throws nearly all the emphasis onto the “theatrical” features of line readings, postures, gestures, and facial expressions.

Moreover, seeing the 3D screening at Toronto right after seeing digital 2D copies, I was struck by how many planes are out of focus in the 3D version. Presumably the 2D transfers have always been taken from one or the other of the dual-camera negatives. The result is a harder-edged image than what 3D creates with its staggered overlap of images.

Focus is extremely selective in the 3D version, with often only a face or even a cheek crisp and everything else significantly softer. For example, it’s not easy to discern in the 2D versions that in 3D, Margo’s face is the only plane in focus in the first shot below; both the bouquet and Mark, as well as everything else, is not as sharp. Later, Hitchcock makes the bedside clock salient by letting it be the only item fully in focus, but I don’t think you’d know that from the harder-edged image on display on the DVD and the download version.

Unlike the 1940s deep-focus style, then, Dial M‘s color 3D puts very few planes in focus, accentuating the shallowness of the space of the scene. The foreground furniture and lamps would be distracting if they were in focus (as, say, they tend to be in The Ipcress File). Like a silent-film director practicing the “soft style” of the 1920s, Hitchcock uses 3D to surround his characters with cushiony, vaguely defined planes.

I’m tempted to see Hitchcock flaunting shallow space in one of the more remarkable moments in Tony’s murder rehearsal. As we’ve seen, high angles trace Tony’s path around the parlor. They also highlight the suitcase that hasn’t been visible in earlier shots, what with all the low angles. But when it’s necessary for Tony to show Swann where he’ll hide the key, we get something quite unlike the rest of the film.

Most directors would either shoot the scene from inside the apartment, framing it in the doorway (as the set is filmed when Hubbard reveals the lost key), or from some vantage point in the hall, probably from rather close to the carpet. Instead we get a cut from the master-shot high angle straight in to another high angle, but taken with a much longer lens.

Peering through the chandelier at Tony’s ploy, riveting our attention on the key, this shot emphasizes depth in a way that few other shots in the film do. Yet the long lens has the effect of squeezing the planes together, negating the effect of 3D and relying on monocular depth cues like distance and the out-of-focus chandelier. It might as well be an axial cut out of Kurosawa.

This image, like the two shots I started with, the implausible and underhanded cut showing Margot displaying her key to the three men, reminds us that Hitchcock is always ready to tell stories of the unexpected, in unexpected ways. And these ways celebrate the ability of film to transform whatever it touches.

Years after Dial M, Hitchcock may have soured on the theatre-driven phase of his career. Yet Wordsworth’s sonnet in praise of sonnets celebrates what you can accomplish within a “scanty plot of ground.” By embracing the theatrical trappings of Dial M for Murder, Sir Alfred does more than tell a suspenseful tale. He fastidiously demonstrates that cinema’s power is unpredictable.

At Toronto, the digital version of Dial M was shown in the original 1.85:1 aspect ratio. The 2004 DVD employs a 4:3 ratio. The version circulating on iTunes HD rental and the 3D Blu-ray disc announced for October, are in 1.77. I’m drawing my frames from the 1.77 version, the closest I can get to the original release.

The 4:3 DVD is not the full-frame film that was recorded in camera. The 1.77 version of Dial M that I worked from includes more material on the sides than can be seen in the DVD release. Correspondingly, a little is trimmed from the top of the 1.77 shots and more is cut from the bottom, and these portions are visible on the DVD. For those who want to study Hitchcock’s visuals, the forthcoming 1.77 Blu-ray is probably to be preferred. But the 1.33 version offers a chance to see how that shot of Margo’s hand was made. Some lady was apparently kneeling underneath the camera.

Speaking of cameras, initial publicity for Warners’ switch to 3D refers to the creation of an “All-Media Camera” that could shoot any aspect ratio and either 2D or 3D. There is evidence that Hondo and subsequent releases were shot on this device; its workings are explained here.

The 1981 Toronto Festival of Festivals’ screening of Dial M is covered in Sid Adilman, “‘Chariots’ Races to Most Popular Film Nod At Toronto Fest,” Variety (22 September 1981), 6. Variety‘s original review of the film is available in the 27 April 1954 issue, p. 3.

Thanks to Steven Jacobs for permission to reproduce his floor plan of the apartment. It originally appeared in his The Wrong House: The Architecture of Alfred Hitchcock (010 Publishers, 2007). Wesley Aelbrecht executed the drawing. Steven analyzes the use of the set on pp. 101-109.

Information on 3D during 1952-1954 comes from three standard sources, Adrian Cornwell-Clyne’s 3-D Kinematography and New Screen Techniques (Hutchinson, 1954); New Screen Techniques, ed. Martin Quigley, Jr. (Quigley, 1953); and R. M. Hayes, 3-D Movies: A History and Filmography of Stereoscopic Cinema (Scarecrow, 1989). See also Thomas M. Pryor, “Warners Reviving Full Film Output,” New York Times (25 June 1953), 23, and “3-D Looks Dead In United States,” Variety (26 May 1954), 1. Some rules for shooting 3D are formulated in Charles G. Clarke, “Practical Filming Techniques for Three-Dimension and Wide-Screen Motion Pictures,” American Cinematographer 34, 3 (March 1953), 107, 128-129, 138.

3-D Film Archive, an invaluable website stuffed with rare images, is run by Bob Furmanek. Particularly helpful entries are here and here. Also check the Home Theatre Forum for posts by Bob.

Hithcock’s remark about 3D creating “waste space” is quoted by Barbara Berch Jamison in “3-D Spells ‘Murder’ for Alfred Hitchcock,” New York Times (11 October 1953), X5. The passage is somewhat opaque, though, and Hitchcock might instead, or also, be referring to the widescreen format. Other quotations come from François Truffaut, Hitchcock (Simon and Schuster, 1967), pp. 156-159 and the 1963 interview “Hitchcock” by Ian Cameron and V. F. Perkins in Alfred Hitchcock Interviews, ed. Sidney Gottlieb (University Press of Mississippi, 2003), p. 51.

Hitch’s comments on editing versus long takes come from two essays, “Direction,” from 1937, and “My Most Exciting Picture,” from 1948, a transcribed interview. Both are available in Hitchcock on Hitchcock: Selected Writings and Interviews, ed. Sidney Gottlieb (University of California Press, 1995), pp. 253-261 and 275-284.

For information on Hitchcock’s career, I’ve drawn on Patrick McGilligan’s Alfred Hitchcock: A Life in Darkness and Light (HarperCollins, 2003) and Donald Spoto’s The Dark Side of Genius: The Life of Alfred Hitchcock (Little, Brown, 1983). See also Bill Krohn, Hitchcock at Work (Phaedon, 2000), p. 130.

Bazin’s essay, “Theater and Cinema,” is available in What Is Cinema? vol. 1, ed. and trans. Hugh Gray (University of California Press, 1967), pp. 76-124. My quotation of the stage directions from Knott’s play come from Frederick Knott, Dial “M” for Murder (Dramatists Play Service, 1954), p. 37. You can read Wordsworth’s “Nuns Fret Not at Their Convent’s Narrow Room” here.

Kristin discusses German Kammerspiel films in our Film History: An Introduction, pp. 95-96. Her remarks on the genre and on Backstairs can be found on Antti Alanen’s blog. I consider Dreyer’s treatment of kammerspiel conventions in The Films of Carl-Theodor Dreyer (University of California Press, 1981). The first essay in my Poetics of Cinema connects Rope with 1940s trends in long-take shooting and the “fluid camera.” See as well Herb A. Lightman, “The Fluid Camera,” American Cinematographer 27, 3 (March 1946), 82, 102-103, and “‘Fluid’ Camera Gives Dramatic Emphasis to Cinematography,” American Cinematographer 34, 2 (February 1953), 63, 76-77. Some of these ideas are discussed in our blog entry, “Bergman, Antonioni, and the Stubborn Stylists.”

I’m grateful to Cameron Bailey, Jesse Wente, Andrew McIntosh, and Brad Deane for enabling me to participate in the screening.

P.S. 12 Sept 2012: Richard Allen of NYU points out to me that John Orr, in his book Hitchcock and Twentieth Century Cinema explores Hitchcock’s Kammerspiel affinities in Dial M and other films. “It is Hitchcock, not Lang,” Orr writes, “who renews the European Kammerspiel tradition in the age of sound and Hollywood colour” (p. 63). I regret that I haven’t read that book, but now I intend to! Excerpts available on Google books suggest that my arguments go in different directions than Orr’s. In any event, Orr is a distinguished film scholar whose work always rewards attention.

P.P.S. 16 Sept 2012: I should also have referenced the special 3-D issue of Film History 16, 3 (2004), which includes articles by William Paul and John Belton, among others. In another essay, Sheldon Hall discusses Dial M, concentrating on manipulations of point-of-view, with other material on the film’s relation to the play. The whole issue is well worth reading, and I regret not recalling it when writing this entry.

P.P.P.S. 11 Oct 2012: At Twitchfilm, Jason Gorber provides thoughts on the digital restoration and an interview with Jesse Wente, who supervised the programming of Dial M for TIFF.

P.P.P.P.S. 11 Oct 2012: At 3Dfilmarchive.com, Bob Furmanek and Greg Kintz provide a dazzling consideration of the new restoration and the Blu-ray release, along with detailed production background and many original documents. Using production documents and photographs, Bob indicates that the Warners All-Media Camera was used on Dial M, and my entry has been revised to reflect the likelihood that this was the case. I’d appreciate further information from interested readers on that gadget, beyond the usually cited passages from John Wayne’s Hondo correspondence. A minority opinion claims that the machine was unworkable and Warners films were shot in the Natural Vision system, but I’ve seen no evidence that would support this. Thanks again to Bob for keeping me in the loop.

Clocked doing 50 in the Dead Zone

DB here:

August’s final weekend fizzled. Ray Subers of Box Office Mojo writes:

The Expendables 2 repeated in first place on what was easily the lowest-grossing weekend of 2012 so far: the Top 12 added up to $83.8 million, or 12 percent less than the previous low (Feb. 3-5).

This late-summer slot is usually a problem. Here’s Subers on last year’s situation, which included Hurricane Irene.

The weekend as a whole . . . is poised to be one of the slowest of the year, hurricane or no. . . . This crop of new releases [Columbiana, Don’t Be Afraid of the Dark, Our Idiot Brother] is modest at best, though Irene has given Hollywood a convenient excuse.

With few exceptions, both winter and summer have stretches which make it hard for new releases to make headway. January through March and mid-August through September are forbidding Dead Zones. Is it a vicious cycle? Do audiences stay away at these times because most releases have little appeal? Or do the distributors treat these months as dumping grounds because people tend to stay away?

Some years back, I pointed out that often these barren months yield some good, unpretentious fruit. This is the realm ruled by our B films–the action pictures, romcoms, modest dramas, and low-budget fantasy and science fiction that give the theatres minimal reasons to stay open. Often the Dead Zone can yield modest, interesting movies that escape the hyperbole that surrounds bigger productions. My example in 2008 was Cloverfield, which actually made decent money in wintry down times. Last year, there were Lone Scherfig’s One Day, Steven Soderbergh’s Contagion, Nicolas Winding Refn’s Drive, and probably others I missed.

I saw only one new release in the 24-26 August window, Premium Rush. It seems to me one of the best mainstream movies I’ve seen this year, and its weak performance ($6 million on the weekend) just shows that you can’t judge by box-office numbers. I found it much more enjoyable as a movie, and more intelligent in its grasp of storytelling and audience uptake, than Marvel’s The Avengers (opening weekend $207 million) and The Dark Knight Rises ($424 million), the two hulks looming over the season.

If Truffaut is right that cinema gives us beautiful people who always find a parking space, Premium Rush is pure cinema. The gallery of characters presents hip youngsters of Benetton gorgeousness (white guy/ African American guy/ Hispanic woman/ Chinese woman/ Indian guy) up against a middle-aged white guy with an ominously overhanging lip that makes him look both stupid and perpetually peeved. Needless to say, Michael Shannon has fun with this. And the couriers always find a place to lock their bikes.

It’s also a real Manhattan movie, which is to say it invokes welcome prototypes: frantic bustle, fast talk, quarrelsome strangers, good cops, bent cops, dumb cops, collisions born of congestion, chance encounters that become significant, violence courtesy of a mafia (Chinese), and moments of casual kindness. We’re all Saroyans when it comes to the Big Apple. We endlessly sentimentalize this city in our movies, and they’re probably the better for it.

But to make a more analytical case that this is a smart, well-put-together movie, I must indulge in spoilers, which are coming right up.

Bike boy

Premium Rush is short: 83 minutes and 49 seconds, not counting credits. That’s also about the length of G-Men, The Ghost Goes West, Holiday, Shopworn Angel, Phantom Lady, The Dark Mirror, Pitfall, The Suspect, Baby Face Nelson, and the 1953 War of the Worlds. I’m not proposing length as a yardstick of value, only noting that our two-hour-plus blockbusters have forgotten what you can do in short compass.

In many B-pictures, both now and then, brevity can encourage you squeeze diverse possibilities out of a simple situation. In Premium Rush, the central situation exemplifies the screenwriter’s old adage: Swamp your protagonist with problems. Here they come fast.

At 5:17 pm, Manhattan bike messenger Wilee is assigned to pick up an envelope from Nima, a Chinese woman who works at Columbia University. He’s immediately pursued by a cop, Robert Monday, who wants what’s in the envelope. At the same time, Wilee and his girlfriend Vanessa, also a messenger, are quarreling because he missed her graduation ceremony. A heavy make is flung Vanessa’s way by Manny, an African American Adonis who’s Wilee’s only rival in virtuoso biking. And at intervals Wilee, who shoots through traffic with suicidal glee, is in the sights of a bulky bike cop. All jammed together we have a free-spirited protagonist who’s quit law school because he loves to ride, a love triangle, a sinister cop, and a mystery: What’s in the envelope? By 7:00 pm all is resolved.

The film displays the classic Hollywood double storyline–romance problems and work problems, intertwined. Still, the plot isn’t as linear as I’ve just implied. I think that the film exemplifies clever ways of working with the four-part structure that Kristin has identified as common in Hollywood features. (That’s discussed here and here and here.) My timings aren’t as exact as I’d like, but I think they’re decent approximations.

Setup (0-ca. 28:00)

After the flash-forward prologue, set at 6:33 pm, and the brief exposition of Wilee’s world view, we see him picking up the envelope at 5:17. It’s addressed to Sister Chen in Chinatown and it must arrive by 7:00.

In a chase Wilee evades Monday and the bike cop, and goes to a police station to file charges against Monday. But he has to take cover when Monday comes in. Now the film’s narration gives us a block of scenes that flashes back to earlier in the day, starting at 3:47. We see Monday lose thousands of dollars in Chinese gambling parlors. Punished by the loan shark’s thugs, he kills one of them. To make amends, he agrees to intercept a ticket that’s worth $50,000 that’s making its way to Chinatown. At the end of the flashback, Wilee, hiding in the police station’s men’s room, opens the envelope and sees that what’s inside is simply a movie stub with a Smiley scrawled on it.

In a chase Wilee evades Monday and the bike cop, and goes to a police station to file charges against Monday. But he has to take cover when Monday comes in. Now the film’s narration gives us a block of scenes that flashes back to earlier in the day, starting at 3:47. We see Monday lose thousands of dollars in Chinese gambling parlors. Punished by the loan shark’s thugs, he kills one of them. To make amends, he agrees to intercept a ticket that’s worth $50,000 that’s making its way to Chinatown. At the end of the flashback, Wilee, hiding in the police station’s men’s room, opens the envelope and sees that what’s inside is simply a movie stub with a Smiley scrawled on it.

Complicating action (ca. 28:00-48:00)

A plot’s second stretch is often a complicating action, something that changes the protagonist’s goals. Originally Wilee wanted to fulfill the delivery; now, with things getting dangerous, he decides not to. He goes back to Columbia to return the envelope to Nima.

At this point we get a flashback explaining that the ticket is a token from a Chinese crime lord, whom Nima has paid with her savings. In the meantime, Monday finds a new stratagem. Instead of trying to catch Wilee, he calls the messenger service and, citing the number on the receipt he has wrested from Nima, he changes the dropoff point. Raj, the dispatcher, gives the order to Manny, Wilee’s rival, and Manny fetches the envelope moments after Wilee has returned it.

We’re at about the midpoint of the film when Nima explains that the money is payment for her son’s illicit passage to America. Now Wilee is faced with a classic choice for an American protagonist: To mind your own business, or to risk your life and livelihood to help someone in distress. He chooses to be a hero, and that means catching up with Manny.

Development (48:00-64:00)

The development section usually doesn’t radically change the premises of the plot. Instead, it’s used to define character further, flesh out secondary aspects of the situation, rework motifs, build suspense, and, surprisingly, simply delay the conclusion. Premium Rush offers a good example of several of these functions. Pedaling frantically after Manny, Wilee phones him and offers him money to give him the envelope. Manny could have accepted, and that would initiate the climax right away.

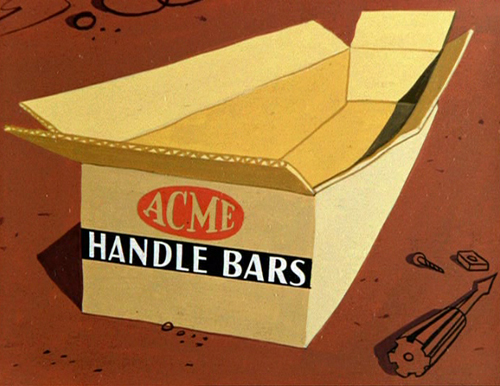

But Manny is a competitor. We’ve seen that he has his eye on Vanessa and he’s convinced he could beat Wilee in a race. So Manny’s personality, agreeable but aggressive, motivates delay, in the form of a prolonged chase/race that, inevitably, brings in the bike cop yet again. Meanwhile, the fact that Vanessa happens to be Nima’s roommate, and that she first put Monday on Nima’s trail, puts her into the mix, pedaling fast to converge with the three men. When she and Wilee finally meet, he hides the ticket in his bike’s handlebar, creating preconditions for the climax.

But Manny is a competitor. We’ve seen that he has his eye on Vanessa and he’s convinced he could beat Wilee in a race. So Manny’s personality, agreeable but aggressive, motivates delay, in the form of a prolonged chase/race that, inevitably, brings in the bike cop yet again. Meanwhile, the fact that Vanessa happens to be Nima’s roommate, and that she first put Monday on Nima’s trail, puts her into the mix, pedaling fast to converge with the three men. When she and Wilee finally meet, he hides the ticket in his bike’s handlebar, creating preconditions for the climax.

This section builds to a pile-up that ends with what we saw at the film’s beginning: Wilee sailing across the frame and landing on the pavement. Dazed, he remembers meeting Vanessa at a bar, where he won a prize as top messenger–the prize being the bike he’s been riding. Each of the three sections we’ve seen includes a flashback, but this is the first one presented as a character’s memory.

Climax (64:00-83:49)

One sign of a climax is this: We know everything we need to know. We know what the ticket means, what all the characters want, and what the stakes are. Now we just have to watch their plans work. In the ambulance, Wilee is suffering from cracked ribs, and Monday bends over him, whacking the ribs to make him talk. Wilee admits that he’ll tell everything if he can get his bike back. This is the make-or-break moment: The hero has to find a subterfuge that will accomplish his goal. Recovering the bike will allow him to retrieve the ticket.

The film has relied on crosscutting throughout, but now the technique expands and accelerates. Nima heads for Chinatown. Wilee’s bike is taken to the police impound facility, but Vanessa has followed it there and gets inside. Soon Wilee arrives with Monday, who searches Manny. Inside, Wilee and Vanessa recover the ticket and escape, courtesy of some very flashy bike-riding. They split up: Wilee to deliver the ticket, and Vanessa to assemble a flashmob.

From the start, during Wiley’s voice-over exposition, we’ve been aware that the couriers form a sort of countercultural community, and a very early scene showed bikers stopping to help fallen comrades. (Good old foreshadowing.) Now, as Wilee goes to deliver the ticket, he faces Monday, who has again caught up with him. The messenger community appears and Monday realizes he can’t fight them all. He’s killed by a Chinese gang member, introduced in part 2 and seen en route to the Chinatown showdown.

Wilee delivers the ticket to Sister Chen, and she phones the snakehead in China to report that the boy’s passage has been paid. Nima thanks Wilee, and in a canonical wrapup Vanessa and Wilee embrace. A brief epilogue echoes the beginning by showing Wilee back whizzing through the streets. “Can’t stop. Don’t want to.”

In Storytelling in the New Hollywood, Kristin points out that a film of 80-90 minutes might have only three parts, each 20-30 minutes long. I prefer my layout because it lets each of the first three sections have its own flashback, and it highlights the midpoint–the crucial moment of choice for Wilee. But proponents of a three-act structure would claim that their model accounts for the movie too. The setup would then run to the point at which Wilee escapes from the police station and calls Raj to tell him he wants no part of the deal; the complicating action would consist of Manny’s pickup and the ensuing chase; and the climax, as with my breakdown, would start when Wilee confronts Monday in the ambulance. In this respect, I think Premium Rush would be an enjoyable film to use in teaching some different approaches to Hollywood dramaturgy.

Personal velocity

From another angle, the first three parts (or two, if you insist) are themselves flashbacks from the opening shots. We’re introduced to Wilee as he sails against the sky in slow-motion, hurled from his bike and en route to hitting the pavement. Then in a kind of prologue the narration takes us back to him enthusiastically pedaling through the streets at 5:10 that day. His voice-over confides his love of biking, his refusal to use gears or brakes, and his preternatural ability to avoid collisions. In Wait Frank Partnoy shows how well-practiced athletes slow down their perception of time, giving themselves 200 milliseconds or more to decide how to return a tennis serve or a cricket shot. Thanks to CGI that plays out Wilee’s options within a split second, we see that he has that gift.

You can criticize voice-over exposition like Wilee’s as lazy screenwriting, and sometimes it is. But given the time pressure, both in the story’s deadlines and by the movie’s length, it creates a concise lead-in that sets the rapid pace of the little adventure we’re going on. The same pace informs the layout of the situations.

During the prologue, Vanessa gets concisely characterized. Nearly sideswiped by a cab, she punishes the driver by using her bike chain to amputate his outside mirror. Six minutes into the movie, Wilee gets his assignment; three minutes later he’s picking up the package. A minute or two after that, he’s accosted by the cop Monday. Then we’re off on a swift chase scene, shot and cut with a precision and economy largely missing from the two movie hulks mentioned above. The many stunts–most of them practical ones, not CGI-created; and many quite funny–keep you riveted to the screen. Likewise, the cascade of deadlines gives every scene a time pressure that’s only enhanced by hairbreadth escapes and near-misses in traffic.

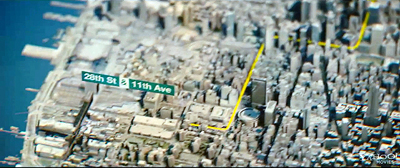

Rapid pacing lets you slip smart things in casually, like the fact that Monday goes by the alias of Forrest J. Ackerman. The use of vaguely Googleized 3D maps, with Wilee’s route traced in yellow and his hypothetical zigzags in white, keeps us oriented briskly. Wilee’s swift, insolent repartee yields comic motifs, which I won’t spoil by specifying. Even the product placement has a jokey quality: these purportedly cool kids are stuck in a Columbia movie, so they all must use Sony Ericsson cellphones (1.8 % global market share last year).

The film employs the redundancy necessary to the Hollywood tradition, but in quickfire fashion. So, for instance, we learn in little bursts that Wilee rides without gears or brakes: he tells us, then later we see his handlebars and axles in close-up, still later Manny mocks his Old School simplicity, and then we see close-ups of Manny’s high-end gear. Finding fresh ways to repeat information is a measure of craft skill. You don’t just restate it; you do it once in words, then images, then contrasting images, and so on. But you can do it all so fast it doesn’t seem redundant. The payoff occurs when Vanessa, warned by Wilee that using brakes will kill her, has a serious crash. In one brief shot she angrily whacks off her brakes, bringing herself closer to his hell-for-leather ethic. Blink and you might miss it.

The film’s use of some common current conventions, like impersonal flashbacks that jigsaw together earlier events in different lines of action, adds to the sense of compression. The replays that show how the lines knot together are quick and simple. Above all, I congratulate director David Koepp, who also wrote the film with John Kamps, on avoiding the obvious. Lesser minds would have called our hero Road Runner and made the futile cop the Coyote figure. Wilee the biker combines the Coyote’s cosmic persistence with the Road Runner’s speed and vocalizations. Joseph Gordon-Leavitt’s grinning giggle comes pretty close to a meep-meep.

Above all, the film’s momentum comes from a plot motored by deadline-driven chases. No other medium can render the exhilaration of sheer headlong velocity. From the early 1900s up to today, cinema is drawn toward people, animals, and machines hurtling across the screen. Vanishing Point, Speed and Premium Rush are tapping the appeals exposed by great chases like those in Keaton’s Cops and The General and less-known Harold Lloyd masterpieces like Girl Shy and For Heaven’s Sake. I sometimes complain about post-1960s Hollywood, but I’ve got to admit that the revival of flamboyant set-piece chases in Burt Reynolds and Clint Eastwood movies, Raiders of the Lost Ark, and the action-adventure movies that followed have paid big dividends. Screen action doesn’t have to be rapid, but when it is, and when it involves a race against time, it can be transporting. Sometimes you just want a movie to move.

True, the summer comic-book sagas shift their bulk, but leadenly. When these zeppelins accelerate, they often burst into disjointed imagery. Premium Rush could be a textbook in how to give fast action a clean, cogent profile. When we see energetic movement that’s coherent, unpretentious, and inventive, gracefulness comes along as a bonus. You get another blossom in the Dead Zone.

Assuming that the summer ended on 26 August, Indiewire offers its analysis of summer trends. The most striking news: Overseas box office is about 2/3rds of the total.

Business over Labor Day weekend, which might also be counted as the end of summer, was somewhat stronger, with one robust win (The Possession, at $21 million). Box Office Mojo‘s report from 2 September doesn’t even mention Premium Rush, which is projected to finish Monday with a total to date of about $13.5 million. See also Leonard Klady’s summer wrapup at Movie City News.

Kristin discusses the structural patterns of mainstream American movies in the first chapter of Storytelling in the New Hollywood and offers many examples in later chapters. I test it on more recent cases in The Way Hollywood Tells It.

P.S. 4 September 2012: Thanks to a tweet from K. J. Hargan, I learn of a suit from a writer claiming that the movie is based on a novel he wrote in 1998. [2013 update: The plaintiff lost the case in April.]

P.P.S. 5 September 2012: David Koepp has written me with more information about his goals in making the film.

Nothing about Premium Rush was easy. The extreme nature of the work on the city streets, the physical risks to the actors and stunt performers, and our determination to find our entertainment value in real physical performance rather than CG work (except in certain obvious situations where it was played for laughs) all raised the degree of difficulty in their own way.

But one of the most gratifying things about your analysis was your appreciation of our structure, and how hard we worked to make a film of breathless brevity, in the great tradition of B pictures for decades. I realize that, as far as aesthetic criteria go, “short” doesn’t sound like a terribly high-minded one, but to me it was an essential guiding principle and a hard one to pull off. Your understanding of the value of a brisk pace and a tight running time made me smile, and your respect for the amount of love and effort some of us put into genre work is much appreciated.

Many thanks to David for the kind note.