Archive for October 2012

News! A video essay on constructive editing

DB here:

In connection with our textbook, Film Art: An Introduction, we’ve created several videos examining film techniques. Thanks to Peter Becker and Kim Hendricksen of Criterion Classics and Janus Films, we’ve been able to include clips from film classics, from Ashes and Diamonds to Ugetsu Monogatari. Because our publisher McGraw-Hill sponsored the production of these pieces, most of them are on a dedicated website called Connect, accessible only to students and teachers using the book in courses. We’ve made one video freely available on Criterion’s own site, where Kristin discusses some editing techniques in Agnès Varda’s Vagabond.

But not everybody who reads Film Art is in a course using the online supplements. And some people who aren’t reading Film Art might still enjoy learning more about the topics we cover. Moreover, we’ve had such good response to the Connnect clips that we decided to create a longer, more wide-ranging piece, also suitable for classrooms. So we prepared another video and today are making it available to anyone.

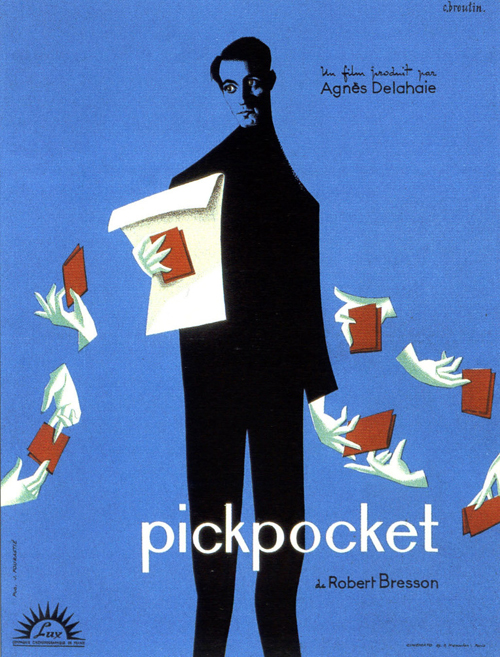

The Connect pieces mostly concentrate on single scenes, whereas this one roams across several films before focusing on a single example. Specifically, we look at the technique of constructive editing, which we discuss in Chapter 6 of FA. The video draws examples from silent films including Harold Lloyd’s Number, Please? (1920) and Lev Kuleshov‘s Engineer Prite’s Project (1918), while our more recent examples include The Social Network and The Ghost Writer. Thanks again to Criterion, the extract we focus on comes from Bresson’s brilliant Pickpocket (1959).

This piece is produced by Erik Gunneson, a local filmmaker who did an excellent job on the Connect materials. I wrote the script and narrated. (A cold I couldn’t shake off betrays itself in my voice.) We did the work in our production facility here at the University of Wisconsin–Madison Department of Communication Arts.

The links flagged above indicate blogs that are related to this new video. Some others are “What happens between shots happens between your ears” and “The Movie looks back at us” and “They’re looking for us.” There’s also “Three nights of a dreamer,” discussing a passage in In the City of Sylvia that may be a slantwise homage to Bresson’s editing technique.

Just to be clear: The twelve-minute video is available to anyone who’s interested. You can watch it below or on Vimeo. Erik, Kristin, and I hope you enjoy it.

PS 4 November 2012: Our discussion of the Kuleshov effect has led some to ask us whether the several videos on YouTube are authentic footage of Kuleshov’s experiments. Alas, they are not, but Kristin and I don’t know their provenance. However, in Oksana Bulgakowa’s documentary on the Kuleshov effect, available on YouTube, there are some fragments of the surviving footage, starting at 4:28. Oksana has also helped complete the experiment by inserting a substitute for a missing shot. In addition, I’m reminded by Joe McBride and Katharine Spring of Hitchcock’s famous explanation of the Kuleshov effect, available on the DVD, A Talk with Hitchcock. An excerpt from that is posted on YouTube, probably illegally.

So these two candidates walk into a bar….

Why are these men laughing?

DB here:

How do we describe political activity? Candidates compete in a race or a contest, they fight for their party’s nomination and attack their rivals, whose positions clash with theirs. The very metaphors suggest stories—a race to a goal, a conflict that yields a winner, a process with a beginning, middle, and end. That is, political discourse is shot through with notions about narrative.

Only relatively recently, though, I think have the press and the public and the pundits and handlers started to use that very term to describe what’s happening. It would take a cultural historian to say why the term has popped up, so I won’t try. What intrigues me as someone who studies narratives (in films, books, plays, comics, etc.) is that by naming what people and institutions do as narrative, writers and readers may have recognized that narratives are artifacts.

More than the other metaphors, it suggests a large-scale construct. A narrative isn’t a momentary skirmish but something shaped by strategy and challenged by accident. A race or fight just happens, but a narrative is built.

“Lugar defeat fits Obama campaign narrative,” says a headline in the Los Angeles Times. It summarizes a story suggesting that Richard Lugar’s primary loss in May is one piece of the Democrats’ broader account of how the Tea Party has taken over the Republican party. This week, of Mitt Romney’s fifteen years at the top of Bain Capital David Stockman writes, “According to the campaign’s narrative, it was then that he became immersed in the toils of business enterprise.”

If we ever thought of a candidate’s personal history or a surrogate’s summary of current events or a news reporter’s account of a day on the campaign trail as a simple chronicle, we may think so no longer. Narratives, our media now seem tacitly to recognize, are made things–assembled selectively, bent to a simplified arc, and shaped for ultimate impact.

That doesn’t make them fiction, but it does invite us to probe them skeptically. Stockman, for instance, goes on to argue that Romney doesn’t fit our standard idea of a businessman because he is someone who buys, packages, and resells “the castoffs of corporate America.” He was not a manager but a “master financial speculator.” A story can be changed or challenged, retold from another point of view, imbued with mysteries and surprises. By making our political life into a vast tangle of narratives, and narratives about narratives, our media have made us more aware that we are nearly always telling each other stories.

Two tales and their tellers

In 2008, I tried bringing some tools of “narratology” (yes, there is such a word) to bear on the US presidential campaigns. For background on my project, you can visit the original post. That drew on three bodies of stories—the development of the campaigns in the press, some self-generated material from the campaigns (especially Obama’s use of everyday citizens’ own narratives), and above all the book-length memoirs by the top candidates: McCain’s Faith of My Fathers and Obama’s Dreams from My Father. Today I’ll focus just on the current candidates’ own tales, as presented in Mitt Romney’s Turnaround: Crisis, Leadership, and the Olympic Games and Barack Obama’s The Audacity of Hope: Thoughts on Reclaiming the American Dream.

Why these? Why not, for instance, Romney’s more recent No Apology: Believe in America? That book is almost wholly a series of statements on policy. Those are accompanied by some narratives tracing Romney’s version of long-term and short-term trends in world history. A few more personal stories are embedded, but on the whole No Apology is less a memoir than a manifesto. By contrast, Turnaround tells the story of Romney’s three-year tenure at the head of the committee preparing the 2002 Winter Olympics. It offers much more in the way of characterization, decision-making, and drama than does No Apology.

The Audacity of Hope has a policy dimension too, certainly more than Dreams from My Father does. But Obama weaves his points about public issues into a personal story about his involvement in state and national politics. As we’ll see, that allows him to present his ideas as ones emerging from his life story and his daily duties as a senator.

There’s another reason for pairing these books. Turnaround was published in 2004 and reprinted in paperback in 2007, when Romney was launching his bid for the 2008 Presidential nomination. Obama’s Audacity of Hope was first published in 2006 and was reprinted in paper in July 2008, almost immediately after Hillary Clinton conceded the primary contests. The books thus align snugly in one time frame, and each had an afterlife as a bid for campaign support.

I’ll simply take authorship as a given. Obama, as is widely recognized, writes his material himself. (No, I haven’t seen good evidence that Bill Ayres is the ghost writer.) Romney explains that he dictated and revised Turnaround, with editorial and research assistance from others. As with Obama, since Romney put his name to the book, I’ll treat him as the author.

Reality is infinitely amorphous, so to make a narrative out of it you must ruthlessly simplify. In what follows, I won’t be tracing what each writer may have strategically omitted. For example, in Turnaround Romney reports noncommittally that Mattel paid $1 million plus a percentage of revenues for a licensing deal for Olympics-related toys (p. 217). He doesn’t mention that Bain Capital was then a major stockholder in Mattel. I haven’t found any piece of journalism that systematically reviews Obama’s and Romney’s work for omissions like this, but I mention them because we need to remember that nonfiction narratives are necessarily selective. I also want to show that even in the absence of such information, we can still measure the impact of the yarns our leaders spin.

From texture to structure

As attentive readers, we might be struck first by the way the books are written—the authors’ styles. For instance, Romney, as you’d expect is brisk and to the point. Why should he take on the Olympics job? He realizes that his wife is right about his abilities.

The more I protested, the less crazy the idea seemed. The more thought I gave it, the more I softened to the idea. Within two weeks, I would make a complete about-face. I would leave friends and family behind and move to Utah. I would walk away from my leadership at Bain Capital at the height of its profitability and take a position without compensation.

I later joked with the press that it was due to an overdeveloped community service gene. And that wasn’t far from the truth (7).

McCain’s Faith of My Fathers, as I tried to suggest back in 2008, has an eloquent bluntness, but Romney’s prose is more generic. It has the virtue of simplicity, with a touch of over-earnestness. I wonder if Romney’s joke really counts as a joke, especially if it’s not far from the truth.

Obama, as in his first book, is more “literary” (odd in a way, since Romney was an undergraduate English major). Instead of short sentences, we get long ones. Instead of simple declarative sentences, we get winding syntax in which appositional phrases pile up concrete details.

For the first time in my career, I began to experience the envy of seeing younger politicians succeed where I had failed, moving into higher offices, getting more things done. The pleasures of politics—the adrenaline of debate, the animal warmth of shaking hands and plunging into a crowd—began to pale against the meaner tasks of the job: the begging for money, the long drives home after the banquet had run two hours longer than scheduled, the bad food and stale air and clipped phone conversations with a wife who had stuck by me so far but was pretty fed up with raising our children alone and was beginning to question our priorities (6).

Obligingly, our authors provide parallel passages for contrast. In each one, a parent savors a moment that won’t last.

Some years ago, my wife, Ann, and I were playing with our children. After a long day of fun and family time, all five of our boys were dressed in their pajamas and slipped upstairs for bed. As the house grew quiet, Ann turned to me and said she wished we could freeze time, to keep them—and us—just as we were then. That’s not possible, of course. As we grow and age, we know that what we leave our children is our most lasting legacy (ix).

Romney turns this recollection into a lesson in patriotism, adding that we must be equally realistic about our country’s future in the face of threat and change across the world. Compare that generic image of a happy home, without many details (even the pajamas are pro forma), with this more customized one.

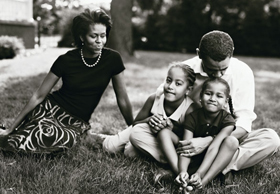

Later that night, back home in Chicago, I sat at the dinner table, watching Malia and Sasha as they laughed and bickered and resisted their string beans before their mother chased them up the stairs and to their baths. Alone in the kitchen washing the dishes, I imagined my two girls growing up, and I felt the ache that every parent must feel at one time or another, that desire to snatch up each moment of your child’s presence and never let go—to preserve every gesture, to lock in for all eternity the sight of their curls or the feel of their fingers clasped around yours. I thought of Sasha asking me once what happened when we die—“I don’t want to die, Daddy,” she had added matter-of-factly. . . (267).

As elsewhere in this book and in Dreams for My Father, you have to wonder if Obama has a photographic memory or is taking novelistic license to create vivid scenes. The string beans, the curled hair, Dad doing the dishes, and the sudden turn to death (counterweighted by Sasha’s asking about it “matter-of-factly”) give the passage dramatic heft, especially as it’s occasioned by Obama’s recollection of watching his mother die. Instead of Romney’s parable of policy we get a meditation on death. It concludes with Obama’s trust that his mother is somewhere rejoicing in her children. Obama has dramatized the continuity of generations that Romney invokes laconically.

We could spend a long time comparing the men’s prose styles, but for now we can say that they point us to larger, narrative issues. The disparities in texture emerge on the large scale as well. One narrative is built on a simple, direct plan; the other is more indirect and meandering. One is designed like an office building, the other like a scenic highway that sometimes doubles back on itself.

Taking his turn

To construct a narrative, you create agents (in fiction we call them characters). You assign them actions. You link those actions by cause and effect. Usually causes that spring from traits or temperaments of the agents, and the effects press them to further action. You invent problems and decision points for your agents, because those things create drama and reveal character. You build in parallels, those echoes of other actions in this tale or others. You invest people, places, and things with symbolic significance. And you bring the whole thing—your plot—to a close that tends to be a resolution of the cascade of actions.

Turnaround’s plot is quite straightforward. After a prologue celebrating the virtues on display in the 2002 Winter Olympics in Salt Lake City, the action begins with a late 1998 telephone call asking Romney to consider taking charge of the mega-event. This is a classic narrative motif that fuses action and characterization. The hero, a man with nothing to prove and no ambitions for glory, is summoned to serve. His modesty is shown by his claims that he’s unsuited for the task. Eventually he’s persuaded, in this case by his wife, and he leaves home to embark on his adventure.

After Romney accepts the task, the plot moves largely in a straight line. Romney’s narration will flash back briefly to fill the reader in on information needed to understand a situation. He suggests that he was drawn to the job by his family tradition of seeking adventure, which leads to an abbreviated history of his ancestors’ flight to Mexico. Another chapter skips back to trace how the SLOC (Salt Lake Organizing Committee) had fractured as a result of a bribery and influence-peddling charges leveled against its top men.

The forward thrust of Romney’s account has a problem/ solution structure. The first and most daunting problem is money, a motif that runs like marbling through the book. The Olympics is under-funded, and its plight is worse than has been reported. Early sections of the book show Romney pursuing sources of cash: sponsors old and new, licensing possibilities, private donors, and the federal government. But the problems keep coming. We learn of marketing failures, the need to rebuild International Olympic Committee support, some unfortunate media coverage, the passivity of the US Olympics Committee, a slide in public opinion, the need to negotiate with Mormon church, and the demands for enhanced security after September 2001. Sometimes an entire chapter is devoted to a cluster of problems.

Romney moves forward on many fronts at once. Occasionally he fails, but he plows on. Despite setbacks, we know that Romney will overcome all these obstacles because the book’s prologue has presented the triumphant beginning and ending ceremonies of the Games. By signaling at the start that the protagonist achieved his goal, all our interest is thrown on the question of how. What will enable Romney to rescue the Olympics? Many factors are invoked, but two are made very salient: Romney’s character suits the task, and he has executive skills that can handle the crisis.

Take character traits first. In the opening pages Turnaround praises qualities of “the human spirit” that are showcased in the Olympics: “determination, persistence, hard work, sacrifice, dedication, faith, passion, teamwork, loyalty, honor, character” (xxii). Without being too obvious about it, these are exactly the traits that the protagonist of Turnaround displays. Romney sacrifices his career by disengaging himself from his stunningly lucrative post at Bain. His family background stresses noblesse oblige, the demand to serve others. He is determined and persistent and full of faith, like his pioneer forefathers but also like the athletes who spend grueling years in competition without any guarantees. He understands that great things require common purpose, whether the team runs a company or plays in a sports event.

Romney usually leaves it to us to infer these virtues in himself, but sometimes he steers us to notice them. He presents himself as passionate, dedicated, honest, and firm.

I pledged fiscal discipline. . . . I vowed to begin reviewing the budget immediately. . . . I was stalwart in my refusal to speculate (35).

The deal was worth about $30 million and . . . I was not about to let it go without giving it my best shot (123).

“I have to level with you,” I said (108).

Steve’s philosophy with the local press was to be entirely forthright and fully accessible. I couldn’t have agreed more. In fact, that’s all I knew (170).

I employed the worst sales strategy known to man: the honest, unvarnished truth (205).

But it’s important that the hero not come across as a chainsaw-wielding Boy Scout. So the Romney of Turnaround isn’t without softer qualities.

I’ve tended to listen to what I feel in my heart about people (57).

It is always the best in humanity that strikes me most deeply (304).

I particularly enjoyed having fun poked at me (85).

Romney also humanizes his protagonist with a few family-centered anecdotes. The height of pathos is reached when the MS-stricken Ann takes part in the running of the torch across the city to the stadium.

After sunset, along a residential street east of Salt Lake City, my family and I waited for the flame to be passed to her. We cheered when she held it aloft; we ran alongside of her on the street and sidewalk as she jogged her 1/5th mile to the next person. . . . There was the love of my life running the Olympic torch down the street. We had wondered if she would be in a wheelchair by that time. Among my children and me there was not a dry eye (347).

Family business

Apart from traits of character, Romney presents himself as prepared to rescue the Olympics because of his experience at Bain Capital. The central symbolic motif of the book is the idea of “turnaround.”

Ann replied, “Just think about it. If there’s any one person ideally suited for this job, it’s you.” She referenced my business experience in turnaround situations. At Bain Capital, we had frequently worked to invigorate underperforming enterprises by utilizing bold and creative maneuvers. I had also been CEO of a consulting firm that had successfully navigated a turnaround (6).

How do you turn a failing company around? Bain has a formula. First, you perform a strategic audit, “a complete review of every aspect of the business.” Then you build a team, selecting choice managers and staff while also motivating them to work together and excel. Then comes “focus, focus, focus”—deciding what few things are critical (54). These steps are followed relentlessly in the book’s overall plot, with chapters devoted to auditing, assembling and deploying staff, and homing in on securing an Olympic-level experience for the athletes and the audience.

Underlying all these steps, and pervading the book’s narrative, is “fiscal discipline.” The problems posed by the Olympics are the classic ones of Waste, Fraud, and Abuse, and Romney sets himself to correct them. There are throughout the book references to what are currently called “takers” in society at large (“patronage jobs, less essential functions, excessive pay contracts,” 111). Contrary to the tenor of current controversies, though, Romney has only scorn for executives and managers who pad their budgets and benefit from freebies. Insofar as Turnaround has villains, they are the previous administrators who let the event be corrupted. They were indicted but not convicted, yet Romney leaves the impression that they were guilty. (“Those who pursued Welch and Johnson were inept,” 23.)

Many big things must be cut. But so must small things, and publicizing those can work to your advantage. Romney notes that the billionaire Bill Marriott (of the hotel chain) once asked for a receipt for a 35-cent toll charge. It’s not just that Bill’s tight with money; he knows that employees and the press will spread the message. This is Romney’s example of “symbolic cuts.” By turning lavish lunches into pizza parties that staff members pay for, Romney shows both insiders and outsiders that his efforts are serious.

The cheeseparing presents a storytelling problem, however. How to keep the hero from looking like a penny-pincher? A few months before the Games open, Romney discovers that the project is in solid financial shape. So he urges that the designer of the big shows plan the fireworks and pageantry as if costs were unlimited. Once the budget has been fixed, the “heart and meaning” of the event can be as spectacular as possible. The book can now end on an upbeat that emblematizes a duality at the heart of Romney’s narrative: Celebrating the triumph of the human spirit is expensive, but ultimately that spirit is more important than money.

After his success, Romney is ready to turn even bigger things around. In the epilogue to the book’s 2004 edition, he explains that he used the Bain formula to run for the Massachusetts governorship. Once he was elected, “The cycle began again: another turnaround” (382).

How did it work out? The prologue added in 2007 claims success. The protagonist managed to get rid of government waste while cooperating with a Democratic legislature. “There are good people on both sides of the aisle” (xi). He turned deficits into surpluses, fought for traditional marriage, supported stem cell research, and took a “truly historic step”:

the passage of a private, market-based health insurance program that would extend coverage to all our citizens. This wasn’t government taking over healthcare and dictating who would get treated for what and by whom. No, it was about personal responsibility replacing government (xi).

Romney emphasizes that this program purged free riders and made everyone, including the working poor, pay something for health insurance.

Having accomplished so much, Romney announces that he feels ready to take the next step. In 2006 he announces his first run for the Presidency.

I know that my love for this country and my experience in bringing change to businesses, to the Olympics, and to Massachusetts would enable me to keep America prosperous and secure (xv).

As in any tale, plot and character coincide: the crisis calls for a leader who has the temperament and the savvy to master it. But the crisis is almost entirely external, leaving no marks on the hero’s psyche. True, Romney harbors some reluctance to take the mission, but that’s a sign of an enduring virtue, his modesty. Once he accepts his mission, he has no doubts and his character doesn’t change. Contrast this with McCain’s conversion narrative in Faith of My Fathers. He starts as a feckless cutup unworthy of his family tradition. Not until his endurance is tested as a tortured POW does he do honor to his father and grandfather. Romney’s character is chiseled in place at the start, and his struggle is a matter of strategy and tactics. The same skill set can be transferred to the problems of a state and to the nation as a whole.

Others don’t receive the same degree of characterization. The members of Romney’s team are quickly sketched, their resumes matched to their place in the hierarchy. Romney’s five sons are barely mentioned, and his wife receives only a little more treatment. Far more important are his mother and father.

References to one’s parents are a basic convention of political autobiography, and Romney sets out both in his characteristically straightforward terms. His mother not only warns him away from caffeine but teaches him the need to serve. His father George Romney becomes an icon of sacrifice (“I grew up idolizing him,” 10), especially for his desire to bring business skills to public service. The measure of the elder Romney’s character is his rescuing his company, American Motors. “He literally risked his net worth on his ability to turn things around” (11). In saving the Olympics, Mitt, like McCain, becomes his father’s son.

The 99 percent

Like Romney’s, Obama’s book starts in the present. He writes as a recent recruit to the US Senate, so again we know how things will end up. Then, like Turnaround, The Audacity of Hope flashes back to earlier moments in Obama’s life. But the time scheme he presents is more complex than Romney’s. And just as the linear pattern of overcoming problems aims to reflect Romney’s speeding-bullet executive style, the braided structure of Audacity suggests the writer’s tendency to circle a problem and study it from several angles.

The Prologue provides a succinct summary of Obama’s career. He leaves his job with a law firm, wins a seat in the Illinois legislature, and in 2000 runs for the US House of Representatives. “I lost badly” (5). He wins a US Senate seat in 2004 and starts serving the following year.

This initial recapitulation of Obama’s career is structurally necessary because the book will be woven out of incidents and ideas from many periods of his life—not just the political career, but his childhood, his days as a community organizer, and the days at a law firm where he courted his wife-to-be. We need a timeline if we’re going to follow all the shifts to come. We aren’t exactly talking Proust here, but Obama does glide freely from the present to different moments scattered through his life, often far out of chronological order.

The strongest anchor is given at the start of Chapter One, when Obama is sworn in as Senator. This emblematic moment will reappear in a later chapter and then at the start of the Epilogue. But Chapter One skips from his oath-taking back to his service in the Illinois legislature, then to his “freak win” during the campaign, then to the present and his relations with sitting senators, then back to his childhood and his college days during the Reagan years.

Even more complicated is the zigzag layout of Chapter 6, “Faith.” It starts with abortion debates during Obama’s Senate campaign, skips back to the lack of churchgoing in his childhood, and then traces his acceptance of Christianity as a young man. Next we’re back to the Senate race and a debate with Alan Keyes, followed by Obama’s visit to a black Birmingham church as a serving Senator. Chapter 8, on world problems, starts in Indonesia, one of Obama’s many childhood home countries, before moving to his college days and his un-PC respect for Reagan. Next he’s a Senator going to Iraq in 2005; a citizen stunned by the 9/11 attacks in 2001; a state senator criticizing the Bush invasion of Iraq in 2002. Then he’s back in Iraq, and finally, at the close of the chapter visiting Russia and seeing the threat of nuclear arms in terrorist hands.

What’s the point of all this back-and-forth? Why not a linear account of his campaigns and the obstacles that he overcame? It’s partly because The Audacity of Hope blends the policy statement with the personal memoir. The chapters are presented as topics, like “Values,” “Our Constitution,” and so on. In this respect it’s like Romney’s second book, No Apology. But instead of setting his beliefs out as a finished declaration of principles, Obama tries to show how reflection and encounters with others led him to think about what he should believe. As his style gives dramatic weight to washing the dishes after a family dinner, the book’s overall design tries to present the process of coming to conclusions about policy.

Moreover, by shuttling back and forth across forty-five years of his life, Obama suggests that he brings a variety of experiences to each topic and has learned that life has many sides. For example, the book articulates his recognition that American foreign policy has been a mixture of isolationism and imperial expansion, and he leads us to this through his first-hand experiences of growing up in Indonesia.

The chapter in which he debates Alan Keyes (above) could easily have been a caricature because, as Obama dryly puts it, Keyes’ self-assurance “disabled in him the instincts for self-censorship that allow most people to naviagate the world without getting into constant fistfights.” Keyes was so unlikely to win the Senate race that “all I had to do was keep my mouth shut and start planning my swearing-in ceremony” (249-250). But Keyes was also a passionate Biblical literalist, and Obama portrays himself as being uncomfortable with the usual liberal responses to Keyes’ militant piety.

He claimed to speak for my religion—and although I might not like what came out of his mouth, I had to admit that some of his views had many adherents in the Christian church (250).

The Keyes debate is a culmination of Obama’s reflection on how he came to Christianity, and he realizes that he has more in common with Keyes than do many liberals who dismiss religion as superficial and ignorant. Incredible as this may seem today, Obama recounts Senate prayer breakfasts in which Rick Santorum and Tom Coburn “share their faith journeys” with “openness, humility, and good humor” (247). He goes on to suggest that liberals must learn to respect and adjust to most Americans’ deep commitment to faith in God.

Shifting the action to and fro across Obama’s life has yet another purpose, one that exemplifies a central concern of the book: the fear of forgetting where you came from. “Stay who you are,” one constituent tells him (122). Obama worries that the poor, the working people, the minority communities, and the struggling middle class will move to the edge of his vision as he embraces compromise and money-driven politics. He even invokes the wealthy one percent.

I know that as a consequence of my fund-raising I became more like the wealthy donors I met, in the very particular sense that I spent more and more of my time above the fray, outside the world of immediate hunger, disappointment, fear, irrationality, and frequent hardship of the other 99 percent of the population—that is, the people I’d entered public life to serve (137).

This worry is given concrete expression in the use of corporate jets. Obama is startled by the amenities he finds on board one of these en route to a meeting with the brains behind Google. But by the end of the chapter (“Opportunity”) he has met union workers, parents of a sick son, and students who go to high school for only half a day because their school district can’t afford to pay full-time teachers. Obama concludes:

These are the stories you miss, I thought to myself, when you fly a private jet (230).

Costs, but what benefits?

Romney gives us very little of the curve of his life: almost nothing about childhood, school, or working at the Bain companies. He comes to us as completely formed and ready for his task. Likewise, he tends to characterize the people around him as finished in their growth. His thumbnail characterizations spell out their gifts for serving in his mission. But Obama meets people who, like him, are still in the process of becoming themselves—children, students, even older people still working out their belief systems.

What little change Romney signals comes from his parents, who taught him civic duty. When given a chance to serve, Romney’s mother asked, “If not me, who?” For Romney, the cardinal virtue of community life is sacrifice. This befits a protagonist who could relax in lifelong comfort but who hears a higher call.

Obama, who scarcely knew the traditional family that Romney celebrates (Turnaround, xiii) and who met his biological father only once, learned from his mother too. When she saw an instance of cruelty or insensitivity, she asked, “How do you think that would make you feel?” (80). The key lesson he learns is empathy. By shifting his story back and forth through time, Obama presents himself as trying to identify emotionally with many people over his life, including those he disagrees with intellectually.

Empathic projection leads the protagonist of The Audacity of Hope to try to see something positive in every opponent, not just Alan Keyes but the judges, lawyers, Congressmen, and professionals who come his way. In his policy reflections, he treats every argument as having some validity. This allows our protagonist to voice self-doubt—an emotion that the Romney of Turnaround never admits to.

For example, Obama opposed Bush’s war in Iraq, but not on grounds of pacifism. He thought it was a war of reckless choice. Still, he supported the ruthless search for Bin Laden and was concerned that Saddam might have weapons of mass destruction. And when Baghdad proved easy to conquer, “I began to suspect that I might have been wrong—and was relieved to see the low number of American casualties involved” (349). Yet after three years of civil war, insurgency, thousands of US deaths, and billions of dollars, Obama came to believe that the invasion had been the mistake he originally suspected it was. Despite all this, when he meets President Bush at his swearing-in ceremony in 2005, he finds him “a likable man, shrewd and disciplined but with the same straightforward manner that had helped him win two elections” (55). They have a friendly conversation. Hate the sin, not the sinner.

Throughout the book, Obama worries. Is he doing right by his wife and children? Family tension is absent from Romney’s memoir, but Obama tells of moments of quarrelling with Michelle, fumbling as a parent and husband (how do you get party bags for a kids’ get-together?) and more seriously wondering—as Romney never does—if the sacrifice of public service is worth the toll it takes on those he loves.

Tentativeness about final judgments and persistent questioning of his own views might lead us to see a Hamlet figure. How does Obama the author solve this problem of characterization? After showing that he scans many sides of a question, he tries to carve out a reasonable middle. In his policy arguments, he tends to start with a core that all sides agree on. Everyone needs to be healthy, all kids need a good education, America needs to remain a model of liberty and civility. He then adduces good points from each side, holding them in balance, as a reasonable way to put core values into practice. It is this strategy, I suppose, that fed the 2008 belief that Obama was “post-partisan.”

In one of the book’s last scenes, he recalls meeting an old lawyer who explained why he couldn’t go into politics. He hated to compromise, he says. For the Obama of The Audacity of Hope, compromise is more than sordid bargaining or betrayal. It rests upon a transcendence of narrow self-interest. It constitutes an ability to see the other person’s ideas and passions as vividly as if they were your own.

Weighing positions in such a way means that confident dogmatism can catch you off-guard. He should have swatted Keyes aside in their debates, but the hyperenergetic windbag got under Obama’s skin. ” In the three debates that were held before the election, I was frequently tongue-tied, irritable, and uncharacteristically tense” (250). The Romney of Turnaround would never feel shaken in this way.

Obama’s storytelling strategies, then, risk making him seem weak. What they could achieve, at least with some readers, is a recognition of frankness, of a man’s realization that he’s prey to human frailties. Romney’s book wants us to admire him, even for his humility, whereas Obama’s tale wants us to empathize—with other citizens, but also with his inner struggles.

From this standpoint, Audacity can offer no fixed finale like Romney’s turnaround successes. For a hero who is perpetually trying to live up to the best he thinks he can be, but plagued by doubts, triumph does not come easily. The book ends on a typically balanced note. He’s happy to have helped people; in an echo of Romney, he recalls Benjamin Franklin saying (to his mother, no less), “I would rather have it said, He lived usefully, than, He died rich.” But then the scale tips toward doubt.

At other times, it seems as if the goal recedes from me, and all the activity I engage in—the hearings and speeches and press conferences and position papers—are an exercise in vanity, useful to no one (426).

He can restore the audacity of hope only by taking a run along the Mall and visiting the Lincoln Memorial–his equivalent of Romney’s Games, a symbol of the virtues he aims to attain.

In their ending is their beginning

One narrative offers a straightforward struggle to solve a problem; the other, a Bildungsroman tracing the education of a young man in the ways of US politics. Each matches its overall structure to the personality of its hero. And each arises and concludes on an appropriate note.

One way to grasp the dynamics of a narrative is to compare the beginning and the ending. Turnaround starts with Romney contemplating whether to take on the Olympics job.

I held a little contest with my five sons to see who could come up with the best tag line for the Salt Lake Olympics. The winner was “It’s all about sport” (xxi).

In this nexus we find both of the book’s concerns: the Olympic spirit and the need to package and brand it so that it can succeed as a business enterprise. The same duality recurs at the very end:

I could have made a good deal more money over the last five years had I stayed at my investment job. It would mostly have gone to the tax-man or to kids who are better off earning their own. Instead, I have come to know many more people and to help many more people I do not know. It’s a currency of an entirely different denomination: it can’t be taxed, stolen, or depleted. The more I have of it, the richer I feel (384).

Even though the passage denigrates pure money-making, public service is compared to executive compensation, and the satisfaction of helping others is conceived as spiritual wealth.

As you’d expect, Obama’s opening and closing are more spacious and ambivalent. At the book’s start he reviews his political career, the strangeness of his name and his desire to enter politics. He offers a quick invocation of a noble tradition in American politics, one of a commonwealth that gives citizens “a stake in one another” (4). But this sentiment is followed by the doubt I mentioned earlier; did he really believe this easy packaging, all these tag lines?

If you are paying attention, each successive year will make you more intimately acquainted with all of your flaws—the blind spots, the recurring habits of thought that may be genetic or may be environmental, but that will almost certainly worsen with time, as surely as the hitch in your walk turns to pain in your hip (5).

The Audacity of Hope begins under the sign of disenchantment, announcing a restlessness that is perpetually dissatisfied with where one is now and that ignores the “blessings” staring one in the face (5). These worries resurface throughout the book.

By the end, though, the decline that Obama had fretted about at the start turns to a satisfaction in public service akin to Romney’s. If Obama has helped people live with a greater measure of dignity, he can feel worthwhile. At that point, standing in his running shorts at the Lincoln Memorial, he can imagine of all those people, from Lincoln to Martin Luther King, from the colonists and slaves to the citizens of today, who have built America.

It is that process I wish to be a part of.

My heart is filled with love for this country (427).

He doesn’t mention money.

I’ve tried to read each man’s book dispassionately and without benefit of hindsight. I read Obama’s book before the first Presidential debate, Romney’s immediately afterward. It would be easy for me to find that Obama’s prevarication in that initial dust-up reveals his characteristic tentativeness about definitive statements. Likewise, I had to resist seeing in Romney’s aggressive debate performance proof that he was little more than a high-powered salesman. (Although he doesn’t love to sell, he notes in his book, he also notes that selling pervades his executive culture.) Yet I’ve tried to resist such projections. Letting each man have his say, taking each at his word, I’ve tried to study their characteristic narrative strategies—which may reflect the men more accurately than one-off comparisons between their books and their public performances.

In my 2008 narratological analysis of McCain’s and Obama’s books, I didn’t state my own political preferences. I could muffle them now, but I don’t see much point. I am a reluctant Obama voter. I disagree with many of his decisions: the gingerly treatment of Wall Street crooks, the incessant drone strikes, our persisting presence in the Afghanistan war he has too long thought justified, the muddling through the mortgage crisis, the continuing unconstitutional measures mobilized by the war on terror.

I think that Obama has sought to be a statesman without being a politician. Yet he has gotten good things done. There is much to admire in what he’s accomplished in education, health care, fuel efficiency, civil rights, and many other domains. Moreover, he faced unprecedented obstacles to doing anything. I don’t know of any president who has suffered the vileness visited on him and his family by forces of ignorance and cruelty. That Obama can push forward with cheerful poise in the face of such endless, naked hatred shows him to be an extraordinary person.

Despite Obama’s hope that “the fever will break” if he wins, we ought to expect that his more promising proposals will continue to be mocked and blocked by the most shameful elements in American society—selfish wealth, bigotry, self-promotion, fear of science and reason, and lack of compassion. Behind these forces are plutocrats and demagogues prepared to make millions of people suffer while they pursue the one thing they prize: power. Mitt Romney and Paul Ryan are their advance men. For me, the choice is grim but clear: gridlock or cataclysm.

Animation in Vancouver

Kristin here:

I didn’t manage to see all the animated films at the Vancouver International Film Festival, but I saw three. That is, I saw two animated features and one documentary about an ambitious and lengthy project that never saw the light of day except in butchered form. The films differ widely in subject and will probably appeal to quite different audiences.

The young

Ernest et Célestine (2012, co-directors Benjamin Renner, Vincent Patar, and Stéphane Aubier) is one of those irresistible cartoons based on a well-loved children’s book series. From 1982 to 2004 , Belgian artist Gabrielle Vincent (1928-2004) created this series, based on the unlikely friendship of a little-girl mouse and an adult bear. The film’s imagery replicates the style of the books’ water-color illustrations (see above). Although the series is not well known in the English-language markets, a few translations have appeared. Most are out of print and apparently very collectible, though there is an English-language volume coming out on November 1. This film version might well foster the popularity of the books internationally.

Bears and mice are here assumed to be dire enemies, a premise set up in the opening as Célestine and her fellow orphans are told a cautionary tale by an elderly lady supervisor. It turns out, however, that mice are Tooth Fairies, and that occasionally involves their visiting bear families to exchange coins for the baby teeth of cubs. Such a mission leads to Célestine visiting a bear family (in the candy shop pictured above) and meeting Ernest, a large bear who vainly attempts to make a living as a street musician. The pair become unlikely friends, and as a result become outcasts living together in Ernest’s cottage in the forest. Eventually each is tried in court for having transgressed the natural boundaries between their species.

Visually the film is charming, though narratively it clearly is intended for small children. Unfortunately the screening I attended had an audience mainly made up of adults, only a few of whom brought children with them. Children accustomed to the break-neck pace of anime and contemporary television cartoons may not have the patience for the calm, leisurely narrative pace in Ernest et Célestine. Young children and those with more appreciation for traditional narratives will delight in it however, and it would be worth seeking it out in art-house screenings and, with luck, in video release. Its message of tolerance and understanding among widely different sorts of “people” is simple but effective.

A book of the art of the film, with illustrations by Vincent, is soon to be released in France.

The old

At the opposite end of the age range is Wrinkles (2012, Ignacio Ferreras), a Spanish animated feature about an elderly gentleman, Emilio, whose adult children become fed up with caring for him as he slips into the early stages of Alzheimer’s. They consign him to a slick, soulless care facility and visit him only rarely at holidays. Discouraged and unhappy at first, Emilio gradually comes to appreciate the small pleasures and support the other “clients” at the home can bring each other (see bottom). His roommate, a cynical long-term resident who practices minor con tricks on vulnerable, disoriented neighbors, nevertheless provides humor and support. A still-healthy wife who has nevertheless come to the facility to take care of her husband, an advanced Alzheimer’s patient, shows that love can bring a trace of reaction even from a seemingly unresponsive person.

The story is touching, and the opening provides a surprise moment that conveys Emilio’s encroaching confusion well. The animation, though fairly limited, is well designed and attractive. The endings for the various patients seem to put a distinctly cheerier spin on the grim advance of Alzheimer’s than one would imagine to be appropriate to the subject. Still, the film looks at the subject compassionately and manages several touching scenes.

The ghost

Vancouver was the venue for the world premiere of Kevin Schreck’s documentary, Persistence of Vision (2012). It deals with animator Richard Williams, who made a successful career running a studio primarily making animated commercials and credit sequences. Back in the 1980s and 1990s I must have passed it on London’s Soho Square dozens of times completely unawares.) One of Williams’ employees also devised the technique for merging live-action and cartoons that was used for Robert Zemeckis’ Who Framed Roger Rabbit? (1988), and perhaps the best-known achievement of Williams’ studio was the animation in that film.

Schreck does a good job of presenting an overview of Williams’ career, but his real fascination is with the one doomed project that Williams pursued for about twenty-five years: a feature-length, absurdly technically complex feature to be called The Thief and the Cobbler. The scene above showing one of the characters performing an elaborate card trick is dazzling to behold. It takes place against a neutral background, but a battle scene, a substantial portion of which is shown in Persistence of Vision, goes much further, combining dizzying shifts through convoluted settings with mind-boggling movements of figures.

Williams’ studio worked on the film from 1964 to 1992, but only part-time, fitting it in among their various commissions. Schreck has tracked down several of the main animators who worked for Williams during substantial stretches of this period, and they give invaluable information about what became a legendary epic. Williams refused to participate, but there is quite a bit of historical documentary footage of him. Much of the original material from the film was destroyed, but Schreck, often with the help of his interviewees and others, tracked down original material in various degrees of completion. Several shivery animated sequences consisting of simple pencil tests are included, as are other scenes in later stages of animation. The result is a precious glimpse into the film that might have been.

Ultimately Warner Bros. committed to finance and release the film. This might possibly have worked, but by one piece of misfortune, design elements for The Thief and the Cobbler made their way to Disney and were, putatively (and plausibly) used for the Genie and other components of Aladdin (1992). This was a blow to the commercial viability of Williams’ film. That, in combination with Williams’ failure to complete it by the contractual deadline meant that The Thief and the Cobbler was turned over to a completion insurer. Somehow (in a deal not explained in Persistence of Vision), Miramax ended up with the project. They stitched together the existing sequences using new footage, including Disney-style musical numbers, something that Williams had been determined to avoid. In 1993 Miramax released a highly revised version of The Thief and the Cobbler.

Williams seems to have been one of those artists who works best when kept on a very tight leash. The man was brilliant when it came to making TV commercials, some of which are shown in Persistence of Vision. He created some memorable credits sequences, also shown. I vividly remember seeing Tony Richardson’s The Charge of the Light Brigade in 1968. That was two years before I took my first film course, but even then I realized that the credits were better than the film they graced:

Williams did some of the late Pink Panther ones, too. Clearly, given a short, immutable length, he could come up with a gem. Similarly, when he worked as a collaborator on another director’s film, as with Roger Rabbit, he apparently didn’t become overly ambitious and unrealistic in his goals. It was apparently this one mad vision that slowly drew him to overstep the bounds of feasibility.

Williams’ legacy will not rest simply in these credit sequences and ads. Nor will it reside only in the images in Persistence of Vision, ranging from jumpy pencil tests to semi-finished sequences (and the sequences included in the unfortunate Miramax version). Williams wrote a book, The Animator’s Survival Kit, initially published in 2002, and, coincidentally, released in an expanded edition just last month. It is considered one of the basis books in the field and is used by amateurs and pros alike. Williams discusses the new edition in a brief clip, and one can see his sincere enthusiasm and also his restless energy. He also gives master-classes in animation.

Whether Williams could ever have created a narrative structure to pull together the brilliant set-pieces on display in Persistence of Vision is another question. Clearly his colleagues still regard him with a mix of admiration, devotion, and exasperation. Schreck’s film hints at a masterpiece that was mutilated and yet also suggests that the masterpiece itself was a elusive vision that was problematic from the start.

We enjoyed meeting Kevin and line producer Sarah Timberlake Taylor at the festival. During the introduction to the second of three screenings, Kevin expressed his surprise at the fact that the first and second screenings were both better attended than he expected. From the Q & A, I gathered that the audience included some animation buffs well acquainted with Williams’ career. The Thief and the Cobbler is clearly well known in the world of academic animation history. Buffs will be delighted that Schreck has pulled together so much material and given us as full a look at this lost film, masterpiece or not, as we are ever likely to have.

We enjoyed meeting Kevin and line producer Sarah Timberlake Taylor at the festival. During the introduction to the second of three screenings, Kevin expressed his surprise at the fact that the first and second screenings were both better attended than he expected. From the Q & A, I gathered that the audience included some animation buffs well acquainted with Williams’ career. The Thief and the Cobbler is clearly well known in the world of academic animation history. Buffs will be delighted that Schreck has pulled together so much material and given us as full a look at this lost film, masterpiece or not, as we are ever likely to have.

One problem that Kevin explained is that he cannot release the film into theaters (or presumably on DVD or VOD). It contains extensive clips of copyrighted material, including the various credits sequences and ads by Williams’ studio, short segments from Aladdin and other Hollywood films, as well as The Thief and the Cobbler in its version released by Miramax. This seems a tremendous pity. Given the historical and critical nature of Kevin’s film, it seems possible that such clips could be justified as fair use.

Much has been made of Room 237, the analytical documentary about Kubrick’s The Shining, which was also shown at Vancouver and other festivals. It has a theatrical release in the USA through IFC. Apparently no permissions were obtained from the owners of the copyrights for The Shining and other Kubrick films excerpted in the documentary, with fair use being claimed. As usual, no court cases have so far been filed, and so it is not clear whether fair use actually applies to such extensive uses of clips in historical and analytical studies. Persistence of Vision seems another clear-cut case of fair use, and it would be encouraging to see a distributor courageous enough to release it outside the festival circuit without “permissions” being sought.

October 21: David Cairns has kindly written to point out that there is an epic fan edit of the original footage of The Thief and the Cobbler. It’s incomplete, of course, but it’s 96 minutes long–and obviously a labor of love on the part of Garrett Gilchrist.

Got those death-of-film/movies/cinema blues?

Night Across the Street (2011).

DB here:

The cinema-is-dead complaint, Richard Brody helpfully points out, is now an established genre of movie journalism. In the last few weeks David Denby, David Thomson, Andrew O’Hehir, and Jason Bailey have in different registers sought to revive this quintessentially empty polemic. I’ve gone on about the tired conventions of film reviewing about once every year on this soapbox. (Try here and here and here and here; Kristin got in some licks too). For now I’ll just say that I’m convinced that the Death of Cinema (or Hollywood, or the Intelligent Foreign Film, or Popular Movie Culture, or Elite Film Culture) is simply a journalistic trope, like Sequels Betray a Lack of Imagination or This Movie Reflects Our Anxieties. In short: an easy way to fill column inches.

These squibs seemed especially damp this time around because while these guys were knocking Hollywood and/or art movies I was enjoying the Vancouver International Film Festival. If you’re willing to watch mainstream entertainments from outside Hollywood, or films that aren’t the bland arthouse fare full of stately homes and British accents, or even films that don’t chop every scene to splintery images, Dr. Bordwell has a cure in mind for you.

Had you been looking for breezy or outlandish entertainment, for example, the Dragons and Tigers wing didn’t disappoint. Helpless, from South Korea, is a thriller built around identity theft. I thought it was clumsily plotted, but it sustains curiousity through the apparently bottomless series of discoveries a man makes about his missing fiancée. Jeff Lau’s East Meets West is a Hong Kong farrago of rapid-fire gags, weird haircuts, references to old Cantopop, and nonchalantly wacko storytelling. Granted, the central idea of making the Eight Immortals of legend into modern superheroes (and one supervillain) is smothered by Scott Pilgrim-style SPFX. Still, I will watch Karen Mok Man-wai and Kenny Bee in anything, albeit for different reasons. Closer to mainstream Hollywood tastes was Nameless Gangster, in which a restless flashback structure traces the rise of a flabby brute from customs agent to top drug smuggler. Yoon Jongbin’s slickly-made film ends with an abruptness that recalls the conclusion of The Sopranos.

Of all the pop-entertainment movies I saw at VIFF, the audience favorite was doubtless Key of Life, a nifty Japanese crime comedy. An amnesiac hitman and a shambolic slacker swap identities in a cunning series of coincidences that brings on some satisfyingly menacing underworld types. Intersecting the men’s misadventures is a hyperorganized OL, or office lady, who determines to find herself a husband within a month. Everything sorts itself out, of course, with one nice wrapup saved for the middle of the closing credits. This is the kind of Japanese diversion I’ve recorded a liking for earlier (Uchoten Hotel and Happy Flight). Hampered by a wretched title, Key of Life probably won’t get US theatrical distribution, although it may make some headway on VOD. Aussie movie maven Geoff Gardner and I agreed that if we had the money, we’d buy the remake rights.

Everything new is old (again)

Tabu (2012).

Form is the new content, they say. (Too simple, but some do say it.) No surprise, then, that part of what appeals in contemporary cinema is its overt reworking of previous styles. Neo-noir is perhaps the most common current example, but ingratiating retro-stylings were on display in more rarefied forms at VIFF.

Part of the appeal is the rediscovery of the glory of the 4:3 aspect ratio. Kristin has already talked about how Pablo Larrain’s No appropriates a seedy U-matic look to tell its tale of 1970s Chilean politics. A similar pastiche effect emerged from Mine Goichi’s All Day, a short that used even grubbier video to parody Japanese family dramas. May we expect to see more VHS-looking movies? I wouldn’t mind.

Silent cinema pastiches are usually lame, as witness The Artist, which scrambles history and treats old films as oddly soft-minded. (No Hollywood drama of the late 1920s would have been built around a protagonist so feeble he tries to commit suicide twice.) Jean Dujardin, and contemporary audiences that adore his film, should catch up with Hayashi Kaizo’s To Sleep As If to Dream (1986), in which the contemporary story is played as a silent film and the rediscovered (fake) old film is accompanied by benshi commentary and music. The “forged” footage in Forgotten Silver also shows how good filmmakers can create convincing, pleasantly anachronistic imagery.

At VIFF, another D & T short, Yun Kinam’s black-and-white Metamorphosis (right) tried to replicate the look of silent cinema. While a family crowds around a deathbed, we get disruptive editing, aggressive depth, and even static flashes (those vein-like seepages into the image caused in old films by cold temperatures). As a retro exercise, Metamorphosis is better-informed and more evocative than what we get in The Artist. Suggestions of Maya Deren and Menilmontant gives these images the aura of having been exhumed from the archive.

At VIFF, another D & T short, Yun Kinam’s black-and-white Metamorphosis (right) tried to replicate the look of silent cinema. While a family crowds around a deathbed, we get disruptive editing, aggressive depth, and even static flashes (those vein-like seepages into the image caused in old films by cold temperatures). As a retro exercise, Metamorphosis is better-informed and more evocative than what we get in The Artist. Suggestions of Maya Deren and Menilmontant gives these images the aura of having been exhumed from the archive.

More celebrated since its Berlin triumph (two awards) is another 4:3 exercise, Miguel Gomes’ Tabu. A vaguely 1920s prologue shows a brooding tropical explorer who has seen his ex-wife as a ghost. Then Part 1 (“Lost Paradise”) takes us to stately black and white imagery of contemporary Lisbon. It’s late in December, and Pilar is concerned about her elderly neighbor Aurora. The old woman is taken to a hospital and asks Pilar to find Aurora’s old lover, Ventura. By the time Pilar discovers him, it’s too late. After Aurora’s funeral, Ventura starts to explain how they met in Africa. Here starts Part II (“Paradise”).

Now the film becomes hypnotic. In Africa, Aurora is married to a sturdy, good-natured colonist, and she can hunt and shoot with the best of them. Ventura and his friend Mario, who’s becoming a pop crooner, are taken into the household. He and Aurora begin a torrid affair. Part II is rendered without onscreen dialogue, but not in exact mimicry of silent cinema. There is piano music, it’s true, and much of the action is carried by letters, as in a lot of silent movies. But there are no intertitles; instead, all the action is played out with the support of Ventura’s voice-over, occasionally supplemented by the young Aurora reciting letters she wrote. Moreover, Mario’s band and his singing are rendered in full lip-synch. More eerily, as Ventura explains the rise and collapse of the love affair, we get highly selective bits of noise—not everything audible in a scene, but perhaps the tinkle of glasses or a faint wind. These become the aural equivalent of glimpses.

“Paradise” gives us silent cinema not replicated, but refracted through memory and romantic longing. In a film paying homage to Murnau (a forbidden romance as in Tabu, the name Aurora recalling Sunrise), Gomes has apparently also sought to give us something like the “part-talkies” of 1928-1929. Those films had full-blown dialogue scenes (as in Part I) and other scenes containing only music and effects (Part II), relieved by synchronized musical numbers (a sequence showing Mario’s band performing by the pool). Tabu recovers something of the strangeness of those transitional films, notably Sunrise itself, while remaining highly contemporary. It knows that we can turn to tradition when we want to rekindle a romanticism that would look high-flown today.

Long live the long take

Beyond the Hills (2012).

At about 16 seconds per shot, Tabu has the same cutting rhythm as some early talkies, like The Black Watch and Hearts in Dixie. Today, as we’ve seen, the long take is increasingly the province of movies that play chiefly at festivals. All other things being equal, a movie with around 1200 shots, like the very popular Danish import The Hunt, will be an easier sell on the arthouse circuit than, say, Beyond the Hills, with only about 110 shots in 148 minutes. It’s a pity. Although The Hunt is a solidly crafted drama in the Nordic enemy-of-the-people tradition, it moves rather predictably across the combustible subject of false accusations of child molestation. Beyond the Hills, by Cristian Mungiu, director of Four Months, Three Weeks, and Two Days, is more enigmatic and demanding.

Voichita is a nun in a rural Orthodox enclave in Romania. She’s visited by her friend Alina. The two grew up as best friends in an orphanage, but Alina went to Germany to work, and now she insists that they must run off together. Voichita resists. Alina claims that Voichita once agreed to this plan. Has the young nun changed her mind and committed to the church? Or is Alina’s plan an idée fixe that Voichita has simply humored, without ever intending to join her? Were they perhaps lovers? Alina’s endless staring at Voichita and her lunges at suicide suggest deep passions at stake.

The refusal to supply full exposition makes characterization enticingly uncertain. Voichita’s wide-eyed sympathy for her friend can be seen as both pliable and stubborn, while Alina’s nearly wordless reprimands imply that Voichita has betrayed her. But perhaps Alina is just asking too much, or Voichita is being too unbending. The couple’s drama is played out against the stringent background of a female community ruled by a priest. Alina is incorrigible, not responding to the gestures of salvation extended to her, and agreeing, stone-faced, that she has committed every sin on a list of over 400. Eventually the pious souls decide that Alina is possessed, and her demons must be exorcised. In a simple gesture of solidarity, Voichita declares something like love for Alina, but too late.

Alternating discreet handheld takes with fixed shots staged in depth, making no concessions to impatience or easy responses, Beyond the Hills recalls the sobriety of Dreyer’s Day of Wrath and Bresson’s Les anges du péché. It plays out in a rougher-textured, muddier world, but it’s no less concerned with the dynamics of compassion and cruelty, dogmatism and eroticism. In each, a woman is ready to sacrifice herself for love. As Romania’s Oscar submission, Mungiu’s film deserves to find an audience in the US.

Long takes were also a specialty of the late Raúl Ruiz, whose penultimate film, Mysteries of Lisbon, won him probably the widest audience of his career. That film displayed his fascination with proliferating stories, but its adherence to a single plane of reality was exceptional in the career of a fabulist who enjoyed confounding all types of realism. In that regard, Night across the Street, his last fully completed work, is more characteristic.

An old office worker is about to retire and is convinced that someone is coming to kill him. While Don Celso awaits his assassin, he fraternizes with his co-workers, with schoolteacher and author Jean Giono, and with others in the hotel where he resides. He also recalls his childhood, when he talked to Long John Silver and went to movies with Beethoven. Eventually the plot shifts levels of reality even more radically, as one séance blends into another, characters shot down in a massacre return to life, and eventually Celso takes credit for inventing the people around him.

Mungiu’s handheld shots have no place here. As in Mysteries of Lisbon and his Proust film, Time Regained, the camera glides through this world with velvety assurance. Sometimes the characters do too, as they seem to ride the dolly or saunter in front of a blatantly unreal backdrop. Ruiz subverts academic cinema by using its well-upholstered technique, but he also mines film history. He revisits tableau staging in the shrewdly split set of Don Celso’s office, and he continues to exploit his more-Wellesian-than-Welles big-foreground technique.

Above all, the boy’s trip to the movies, in an awkwardly tilted image in which the usher usually blocks the screen, pays typically skewed homage to the medium’s enchantment. The mock film of Ruiz’s Life Is a Dream has given way to The Foxes of Harrow, the Hollywood cinema of Ruiz’s childhood.

Land, sea, and sky

small roads (2012).

When one thinks of the long take, James Benning comes quickly to mind, and small roads is true to form—in more ways than one. Forty-seven fixed shots in 102 minutes take us from the Far West to the South and to the Midwest before shifting westward again. The roads are indeed small, far from superhighways and traffic circles. As usual, landscape is the protagonist and slight shifts in image or sound arrest our attention. There are plenty of perceptual teasers. When a distant truck descends the distant sloping road above, it vanishes. Will it re-emerge in the nearer road? At another point, we wonder when, or if a car we hear will appear in the frame.

Hogarth spoke of art that leads the eye “on a wanton kind of chase,” and Benning’s roads—almost never seen from dead center, so we’re not given central perspective—carve oblique or sinuous paths into fields, plains, deserts, and forests. Road signs reenact the curve of the roadway, with carets and squiggles providing spare geometric “readings” of the piled-up surfaces of color and mass. There’s also some synesthesia. In one shot, I thought I heard mist rolling in. The topographies are real but through Benning’s strict scrutiny they become as fantastical as Ruiz’s dreamscapes.

That’s why I suspect that roads aren’t the real subject of the film. They serve as a pretext for Benning’s recurring interests in how wind curls clouds and makes branches tremble, how light outlines trees, how shapes like squat black oil derricks and the textures of fat snowflakes and soggy leaves can command the frame. Now that Benning has moved to digital filming, he has discreetly inserted some CGI. I couldn’t spot any, though one partial moon in daylight looks suspicious to me. No matter. Painterly beauty, along with a certain placid mystery, is enough for any movie nowadays.

At the other extreme lies the bustle of Leviathan, a poetic, quasi-abstract documentary by Lucien Castaing-Taylor and Véréna Paravel. The filmmakers capture a New Bedford fishing trip through GoPro digital mini-cameras worn by fishermen, tossed into a netful of fish, or dragged through the water. Long takes abound here too, but it’s hard to say how many. As in The Man with a Movie Camera, the very boundary between one shot and another is put into question. So is the boundary between us and the space onscreen, as we’re weirdly wrapped in the extreme wide-angle yielded by this lens.

This is what you get when no human eye is looking through the camera. Often, in fact, nobody could look through the lens. No head, let alone human body, could occupy the space of some of these shots. Chains roll out past us from churning greenish darkness, while fish drift and slither on all sides. We’re right next to a gull trying to use its beak to lift itself to another area of the hold. Here the fish-eye lens lives up to its name. The camera bobs in a tank as fish are tossed in and spin aimlessly past. Coasting along the edge of the craft, we dip abruptly in and out of the heaving water, our plunge accentuated by brutal sound cuts. We chase starfish and ride waves, spinning up to watch gulls blotting out the sky. Accelerations of speed (again, Man with a Movie Camera comes to mind) render the action hallucinatory, especially since the shutter can capture foam with strobe-like precision.

One result is a disembodied, dehumanized vision of sea and sky: The camera as flotsam. But we also get bumpy, skittish visions of human labor definitely tied to bodies that harvest the ocean. Work activities are filmed from cameras lashed to the fishermen’s heads or lying on the deck among scallops to be shucked. Most documentary close-ups of artisans’ tasks are taken from far back and with long lenses; here the very wide-angle GoPro lenses not only show tasks from the inside, but their distortions exaggerate each gesture, sometimes heroically, sometimes grotesquely. Either way, human activity has been defamiliarized no less than undersea life.

We start the movie immersed in a welter of details and stay enmeshed for nearly an hour. Only then do we get an “establishing shot” showing the boat deck and mapping the overall process of filling and emptying the nets. And fairly soon after that, as if to parody the usual documentary about fisher folk, we get a four-minute shot of the captain dozing off while watching a TV show (apparently The Deadliest Catch). Leviathan ends with a sequence that brackets the chiaroscuro of the opening, but we no longer see a clam’s-eye-view of being snagged. Instead, we get barely illuminated darkness with whiffs of crimson teasingly darting to the edge of the frame, as if to signal the end, before swerving back to the center, then heading offscreen. Again, Ruiz has the line: Special shadows that give off light.

Ready to declare cinema dead? There is a cure for your malaise. We call it a film festival.

More of my thoughts on Ruiz can be found here and here. His widow Valeria Sarmiento completed his very last project, The Lines of Wellington.

On small roads and digital manipulation, see Michal Oleszczyk’s discussion at Slant and Robert Koehler’s informative review in Variety. In correspondence Benning confirms:

Yes, lots of compositing, but no speed changing, although the border cops are going around 100 mph. . . . Shot 26 has a sky that was filmed the next day about 100 miles away. And yes the moon was out, but that shot is pointing north so I filmed the moon in the southern sky during the day, and put it into the northern sky. All the compositing was done with shots I made; always somewhere nearby. (100 miles is nearby when you circle 2/3 of the US.)

You can learn more about Leviathan from Dennis Lim’s article on the filmmakers in the New York Times. The New York Film Festival provides a lengthy Q & A on its website. See also Phil Coldiron’s “Blood and Thunder: Enter the Leviathan“ in the latest Cinema Scope, with some superb frame enlargements. Above all, don’t miss the extract on vimeo, which gives you a good sample of the splendor of this film.

Leviathan (2012).