Archive for November 2012

Classics on DVD and Blu-ray, in time for a fröhliche Weihnachten!

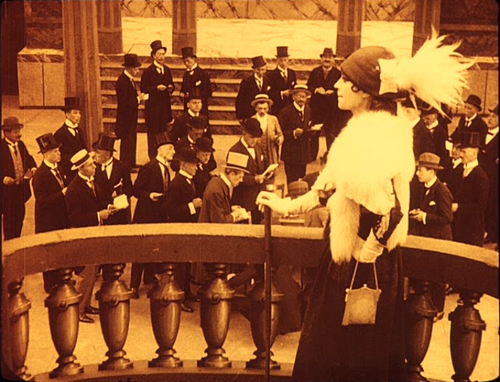

Die Börsenkönigin

Kristin here:

With December holidays coming up, perhaps you’re looking for some DVDs or Blu-ray discs to put on your wish list or to buy for someone. Releases of historically important films in restorations have been prominent lately. The group below has a distinctly, though not exclusively, German accent.

Pabst’s stock going up

Back in the 1970s, when I was in graduate school, G. W. Pabst occupied a central place in the history of German cinema. The standard film studies, like Arthur Knight’s The Liveliest Art and Paul Rotha’s The Film Till Now, emphasized his silent classics, most notably Die freudlose Gasse (The Joyless Street, 1925), Geheimnisse einer Seele (Secrets of a Soul, 1926), and Die Liebe der Jeanne Ney (The Loves of Jeanne Ney, 1927), as exemplars of the “Neue Sachlichkeit” tendency (usually translated as “New Objectivity”). Pabst was the counter to German Expressionism, and yet not all his films fit neatly into the Neue Sachlichkeit. Die Büchse von Pandora (Pandora’s Box, 1929), for example, is a somewhat Expressionistic melodrama.

Indeed, Pabst started his directorial career smack in the middle of the Expressionist movement. Der Schatz (The Treasure, 1923; left) is not bad for a debut film, but it was seldom mentioned in the old accounts of the director’s work. It reminds me of such films as Murnau’s Der brennende Acker, with the Expressionist style being used to portray ancient rural buildings. Der Schatz was long impossible to see, at least outside archives in Europe. I remember liking it when I saw it long ago at the Belgian film archive. The new DVD, from Arthaus Premium, is unfortunately entirely in German, with no optional English subtitles. It’s also Region 2 Pal, so those in the US and other non-Region 2 countries would need a multi-standard player. Still, there are plenty of film courses in German departments these days, and this new issue would be invaluable for research and teaching.

Indeed, Pabst started his directorial career smack in the middle of the Expressionist movement. Der Schatz (The Treasure, 1923; left) is not bad for a debut film, but it was seldom mentioned in the old accounts of the director’s work. It reminds me of such films as Murnau’s Der brennende Acker, with the Expressionist style being used to portray ancient rural buildings. Der Schatz was long impossible to see, at least outside archives in Europe. I remember liking it when I saw it long ago at the Belgian film archive. The new DVD, from Arthaus Premium, is unfortunately entirely in German, with no optional English subtitles. It’s also Region 2 Pal, so those in the US and other non-Region 2 countries would need a multi-standard player. Still, there are plenty of film courses in German departments these days, and this new issue would be invaluable for research and teaching.

The print isn’t terrific, but it’s presumably the best available, and it’s watchable. It comes in a nice package with a little booklet and a whole disc of extras—documentaries on the reconstruction of the film (be forewarned, the new version has modern intertitles with a Gothic font) and interviews with experts. The text on the case claims this is the last great work of German Expressionism. That’s a considerable stretch. Die Nibelungen, Tartuffe, Faust, and Metropolis were yet to come, along with some lesser films. Der Schatz can be ordered from Amazon’s German outlet. (For those who have an American Amazon account, this should work just the same way, with the same password and your address and credit-card information on record.)

Far more famous is Pabst’s second film, The Joyless Street. With its controversial subject matter, involving women forced to prostitute themselves in various ways during the era of hyperinflation, the film was repeatedly subject to censors’ cuts—different cuts in different countries. In my first film course ever, in 1970, I remember seeing what was probably the best version available in the USA at the time, but it was far from complete. At least it still retained a pretty good balance between the Greta Garbo and Asta Nielsen plotlines. Later I saw what was probably the original American release print, butchered down to about an hour. The Nielsen plot, where she plays a character who becomes a rich man’s mistress, was all but gone, with the Greta Garbo plot dominating.

Now the Filmmuseum in Munich has released the latest attempt at restoration on DVD. The accompanying booklet, with some lovely illustrations of set designs and toned frames, has one essay in English. Archivist Stefan Drössler traces the attempts to compile a complete version from many different truncated prints. The original German censor’s records, so often a source of original intertitles for such restorations, are not known to survive. A 1989 restoration by Enno Patalas was the first major attempt to assemble something vaguely like the original. Jan-Christopher Horak initiated another restoration in the late 1990s, drawing upon newly surfaced footage from various archives. It was an improvement, but still probably far from the original. The current reconstruction tweaks that version. Still, as Drössler makes clear, with luck this version is only one more step toward a semblance of the original. More prints may surface—even, perhaps a nearly complete one like the miraculous Metropolis print that was, against the odds, found in South America.

In the meantime, the Filmmuseum DVD is as close as we can get to Pabst’s pioneering move into New Objectivity. There’s still about half an hour missing, but at 151 minutes, there’s a lot more of the film than most viewers will have seen before. Again there is a second disc with documentaries on Pabst, including The Other Eye, an overview of his career. This time there are optional English subtitles, though the format is also Pal.

I was very impressed by the film. It’s a network narrative, coincidentally with the same star who played in Hollywood’s quintessential network narrative, Grand Hotel, seven years later. Most of the main characters live on the same street in 1921 Vienna, where the primary centers for interaction are the queue for the butcher’s shop and the brothel hidden behind a dress shop. There are many characters who come and go in complicated scenes. I was also struck by the use of wide-angle lenses and depth staging (as above). Pabst has definitely gone up a notch in my estimation as a result of this release.

More German films

The great actress Asta Nielsen, who was one of the first international movie stars, had already made an incredible number of movies by the time she appeared in The Joyless Street, most of them German productions. Edition Filmmuseum has also released a collection of four short features Nielsen made during the 1910s. The selection was made to show off her range, with two comedies–Das Liebes-ABC (“The ABC of Love,” 1916) and Das Eskimobaby (“The Eskimo Baby,” 1916)–and two dramas–Die Suffragette (1913) and Die Börsenkönigin (“The Queen of the Stock Exchange,” 1918; see top). She worked frequently with emigré Danish director Urban Gad, to whom she was married, but he directed only the third of these four. The others were respectively made by Magnus Stifter, Heinz Schall, and Edmund Edel. (David’s essay on the Danish company Nordisk discusses some of Gad’s films and his 1919 book on filmmaking.) The films average about 60 minutes each.

Although trained as a stage actress, Nielsen had a remarkably flexible, uninhibited acting style onscreen. She wasn’t afraid to play gawky, plain girls but could also convincingly embody a glamorous woman of the world. Some of her films are terrific, some not so much, but they’re always worth watching for her performances.

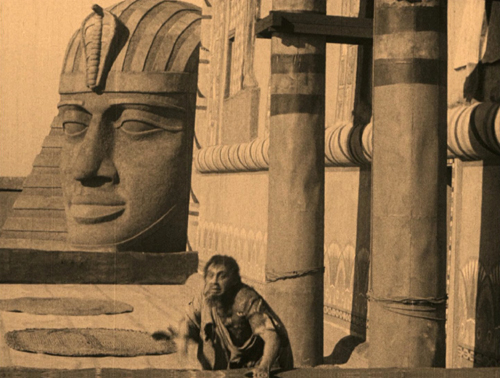

Another recent release is close to my heart, Ernst Lubitsch’s Das Weib des Pharao (1921). In terms of subject matter, it’s not one of his most likable films, with a rather silly plot about a pharaoh falling in love with a commoner. Paul Wegener chews the scenery as a Nubian ruler who wants the pharaoh his daughter instead. But if one can overlook the silliness, it’s a pretty well-made film. The sets are fairly authentic compared with the usual sort of design one encounters in these costume epics, though the notion that a king’s treasure would be inside a giant, hollow statue (see bottom) is pretty risible. Visually, it’s gorgeous, and the print quality in this release is stunning. (There’s a brief film about the restoration, with several of the flashiest shots from the film, here.)

Another recent release is close to my heart, Ernst Lubitsch’s Das Weib des Pharao (1921). In terms of subject matter, it’s not one of his most likable films, with a rather silly plot about a pharaoh falling in love with a commoner. Paul Wegener chews the scenery as a Nubian ruler who wants the pharaoh his daughter instead. But if one can overlook the silliness, it’s a pretty well-made film. The sets are fairly authentic compared with the usual sort of design one encounters in these costume epics, though the notion that a king’s treasure would be inside a giant, hollow statue (see bottom) is pretty risible. Visually, it’s gorgeous, and the print quality in this release is stunning. (There’s a brief film about the restoration, with several of the flashiest shots from the film, here.)

For years, Das Weib existed in only a very choppy, incomplete version running about 40 minutes, discovered at Gosfilmofond, the Soviet/Russian film archive. It was hard to make out the plot. More reels were found in other archives, and a longer version was completed in 2008. Now ALPHA-OMEGA has put together a bang-up package of material. The original score was recorded and matched to the footage to determine a running time of 100 minutes. Footage still missing has, as has become common practice, been filled in with photos, and the plot now makes a lot more sense than it used to. The tinting and toning is based onsurviving footage.

I consider Das Weib extremely important in Lubitsch’s career, as well as in the development of German cinema after World War I. It displays the influence that Hollywood films had on Lubitsch when foreign films were finally let into Germany in 1921 after a nearly five-year ban. To some extent he picked up principles of continuity editing, but it was the new styles of American lighting that he rapidly adopted. He also had the opportunity to work with American cameras and lighting equipment for the first time on Das Weib. The impact of highly directional arc lamps is visible in the frame just above, with its strong back and side light without frontal fill. (I discuss such aspects of Das Weib des Pharao in Herr Lubitsch Goes to Hollywood.)

The extras include the original trailer and a documentary on the restoration. An informative booklet accompanies the disc, including a reprint of program notes I wrote when the film was shown at “Il Giornate del Cinema Muto” in Pordenone. There are optional subtitles in ten languages. The Blu-ray and DVD can be purchased directly from ALPHA-OMEGA. There is no region coding.

Beyond Germany

Back in my senior year of high school I heard a recording of The Mikado and instantly became a big Gilbert and Sullivan fan. Coincidentally a film of The Mikado (1967), performed by the D’Oyly Carte Opera Company, came out just at that time. The D’Oyly Carte company had put on the operettas in their original productions in the 1870s, 1880s, and early 1890s and had toured with the same basic productions almost continuously for about 107 years, until forced out of business for lack of funds. The Mikado film was a straightforward record of the theatrical production, filmed on the stage without an audience present. Over the next 15 years or so I was also lucky enough to see some of the plays onstage in Chicago and London. Apart from being charming works, the productions continued to use the same staging and business as when the operettas premiered; they were a living museum of Victorian theatrical practice. Unfortunately the company finally succumbed to financial woes in 1982; there have been sporadic attempts to revive it, but the traditional staging was finally abandoned, and a link to the past was lost.

Back in my senior year of high school I heard a recording of The Mikado and instantly became a big Gilbert and Sullivan fan. Coincidentally a film of The Mikado (1967), performed by the D’Oyly Carte Opera Company, came out just at that time. The D’Oyly Carte company had put on the operettas in their original productions in the 1870s, 1880s, and early 1890s and had toured with the same basic productions almost continuously for about 107 years, until forced out of business for lack of funds. The Mikado film was a straightforward record of the theatrical production, filmed on the stage without an audience present. Over the next 15 years or so I was also lucky enough to see some of the plays onstage in Chicago and London. Apart from being charming works, the productions continued to use the same staging and business as when the operettas premiered; they were a living museum of Victorian theatrical practice. Unfortunately the company finally succumbed to financial woes in 1982; there have been sporadic attempts to revive it, but the traditional staging was finally abandoned, and a link to the past was lost.

I had long been intrigued by the fact that another version of The Mikado had been filmed in Technicolor in 1939, directed by Victor Schertzinger. I was dubious, in that most of the cast were not D’Oyly Carte members. Indeed, the leading tenor role, Nanki-Poo, was played by Kenny Baker, whose main claim to fame at the time was as a featured singer on Jack Benny’s radio show. Still, the film did use three major D’Oyly Carte players: Martin Green, who took the comic baritone roles, in this case Ko-Ko; Sydney Granville, a bass, who plays Pooh-Bah; and Elizabeth Paynter, comic mezzo-soprano, as Pitti-Sing. (From left to right, Paynter, Green, and Granville.) So, when I learned that our friends at the Criterion Collection had put out a restored version on DVD and Blu-ray, I decided to take the plunge and watch it.

It turns out to be a strange mixture. Rather than filming the production onstage, like the later version, the producers created much larger but stylized sets in sound studios; there’s never a hint of an exterior. The blocking and filming are stodgy, and Kenny Baker is barely adequate to his role. I’m not sure this aspect of the film would win converts to the operetta.

On the other hand, there are the marvelous performances of the three D’Oyly Carte actors, particularly Green and Granville, who were among the greatest members of the troupe during its long history. Having a record of this pair in such important roles is a treasure. And Constance Willis, a British stage actress whose only film this was, does an excellent job as Katisha, bringing in a deft humor that one seldom sees in this dour character. Moreover, the postures and gestures are faithful reproductions of the D’Oyly Carte company’s approach. Until the copyrights ran out on the operettas, those who wished to produce them theatrically were given copies of the scripts with all the staging details written in; these had to be followed exactly. The same was true for both film versions of The Mikado. The poses of the young ladies in “Three Little Maids from School,” with mincing gait, tilted heads, and coyly raised arms, are the same ones that all singers playing these roles would have replicated, as the vintage poster shows:

Ko-Ko’s business with his executioner’s ax in his first number, the Mikado’s gestures in “Make the Punishment Fit the Crime,” and many other moments are also historically accurate. The film even includes the traditional encores for two of the most popular numbers, “Here’s a How-De-Do” and “The Flowers that Bloom in the Spring,” though here there is no live audience demanding them. I saw the D’oyly Carte production of The Mikado three times, and these same songs and no others were always encored. Overall, such a record is invaluable, and definitely makes up for the less entertaining portions.

As always, Criterion’s supplements are strong. Apart from some interviews, a silent D’Oyly Carte promotional film, and a booklet by experts, Ko-Ko’s song, “I’ve Got a Little List,” which was cut from the film, is a very welcome addition.

Finally, I’ll just mention that Kino Classics has put out versions of the 1996 restoration of Louis Feuillade’s 1915-16 serial, Les Vampires. Feuillade is a favorite of ours. (For more on his work, see David’s Figures Traced in Light and our entries here and here and here.) Whether in DVD or Blu-ray, Les Vampires is a must-have, providing 417 minutes of pure, crazy pleasure.

Das Weib des Pharao

Auteurist on the sound stage

River’s Edge (1987).

DB here:

Last November, Joe Dante brought his brand of manic legerdemain to Madison. This year, his pal and contemporary Tim Hunter visited. Tim talked with us about directing, watched an abundance of movies (from 1930s Wellman classics to Hong Kong gunfests), and oversaw a screening of his 1987 classic River’s Edge. A genial presence and 110% cinephile, Tim was continually stimulating. A blog was a necessity.

Grinding it out

Hunter has made several theatrical features, most famously River’s Edge and The Saint of Fort Washington (1993), but for many years he has also been a free-lance director for top television series, mostly on premium cable. Unlike Dante, whose forte is grotesque comedy and satire, Hunter brings a strong sense of dramatic realism to both movies and television. Over twenty years and more than sixty episodes, he has directed major installments of Mad Men, Breaking Bad, Dexter, Deadwood, Law & Order, Cold Case, and Homicide: Life on the Streets.

Apart from efficient craft, he brings to these projects a baby-boomer cinephilia. “I’m an old-school movie brat.” Born in 1947 (about a month before me), he grew up watching classic films. His father was a screenwriter, and in his application interview for Harvard, he won entrance, he thinks, with a rapid-fire analysis of Psycho. As an undergraduate, he ran film societies and made student films. He attended the AFI directors program in 1970 and began teaching film studies at UC-Santa Cruz. Meanwhile, he was writing screenplays. Over the Edge (1979), written with Charlie Haas, was sold to Orion and directed by Jonathan Kaplan. Soon Hunter was able to get backing for Tex (1982), his first directed feature.

As a classic Sarrisian cinephile, he understands that today’s television production resembles the old studio system—particularly its B-level. When he takes a job, he joins a series with an established look and feel, its own formulas and conventions. He’s given a fifty-page script to prepare in a week and to shoot in seven to eight days, with each day lasting twelve hours. On the set he must get through at least seven pages a day to come up with 42-44 minutes of engrossing drama.

As a classic Sarrisian cinephile, he understands that today’s television production resembles the old studio system—particularly its B-level. When he takes a job, he joins a series with an established look and feel, its own formulas and conventions. He’s given a fifty-page script to prepare in a week and to shoot in seven to eight days, with each day lasting twelve hours. On the set he must get through at least seven pages a day to come up with 42-44 minutes of engrossing drama.

As a result, the key question—where to put the camera?—has to be settled swiftly. “You need an efficient plan.” Hunter likes to walk the set a day or two before production begins, in order to figure out his setups and actor blocking. The big decision is whether to used a fixed camera or a “moving master,” a tracking shot that reveals the players and the setting, but one that can be interrupted by closer views. He argues that performers prefer sustained shots. “The longer you can play it, the better for the actors.”

To sustain the shots, most dialogue scenes are covered by at least two cameras. That way the scene can be played out in something like real time, with each camera yielding a continuous take centered on one actor or another. The two camera takes can then be cut together into shot/ reverse-shot patterns.

You can see the efficiency of this. The “Perception” episode of Revenge (2012) contains about 780 shots in 42 minutes; of these, at least 350 are shots that repeat setups. A similar proportion can be seen in Hunter’s first episode of Twin Peaks from 1990; about half of the shots repeat earlier camera setups. Because of the time pressure, the director must stage the scenes with adequate coverage from two or more angles.

This can lead to a routine, zero-degree style: Little complex staging, more reliance on actors sitting or standing. Shoot master shot, reverse angles, and singles for reaction shots. Why not use long-held two-shots or fuller framings, as we find in classical Hollywood studio films? Breaking up the camera takes permits the editor to control when we see facial reactions, to tighten the rhythm, and to eliminate fluffed lines. Quick intercutting also supplies that pepped-up pace that, TV practitioners believe, keep viewers glued to the screen.

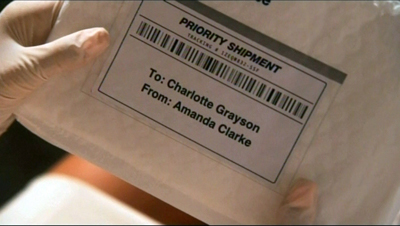

Hunter looks for ways to inject something different, often based on his tastes in classical cinema. For instance, he admires the melodramas of Minnelli and Sirk, so you aren’t surprised to see sudden high or low angles in moments of confrontation. In the “Perception” episode of Revenge, the script gave him a chance for “a Marnie moment.” The heroine Emily has prepared a video that reveals the wealthy Charlotte Grayson’s real parentage. She’s gratified when she sees the maid set the envelope at the foot of the staircase for Charlotte to notice.

Later, overhearing an emotional scene between Charlotte and her father, Emily repents her scheme and tries to retrieve the envelope before Charlotte can find it. Hunter points out that the scene gained suspense when he broke it up into “inserts and moving point-of-view shots.”

The result is a somewhat Hitchcockian byplay, as Emily, startled by the vengeful matriarch Victoria, drops the envelope and tries to keep her from identifying it.

Neatly, Victoria’s face slips into the low-angle view at the very end of the shot, preparing us for her sudden entrance when Emily turns around. And the envelope falling addressee-side down sustains the suspense.

Consciously arty

However much you inject your own emphases, Hunter explained, the director has to assess the visual style of each show and maintain it, so you “tailor your style to the show.” Homicide was 100% handheld, and for that you need a cinematographer who is master of that look. By contrast, Mad Men is more “pictorially precise” and harks back to the studio movies of the 1950s. (Jim Emerson has painstakingly analyzed the felicities of the Mad Men look in several blog entries and video essays.)

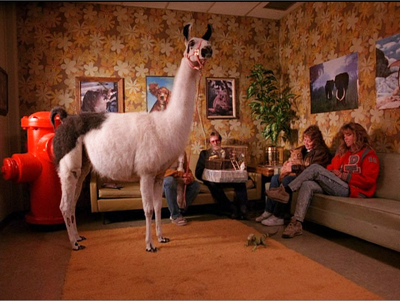

Another pictorially precise show was Twin Peaks, and Hunter’s contribution to the first season (episode four) was one of the most memorable. In that episode we meet Killer Bob’s intimate friend who’s introduced in a shot at once chilling and funny. “Keep your hands where I can see ’em,” snaps Sheriff Harry Truman, and we get this.

At other moments, in an echo of 1940s deep-focus, Hunter uses split-focus diopters to keep foreground and background plane crisp.

The opening displays the sort of calm assurance that Hunter could bring to a show that was, as he put it, “consciously arty.” A moving master takes us from a photo of the dead Laura to Deputy Andy sketching Killer Bob to Sarah Palmer giving her description; it ends on a framing of Donna, taking it all in uneasily. Donna won’t move or say anything in the scene, but this shot’s ending prepares for both the final shot and her expanding role in the episode’s plot.

In the course of the scene, Hunter supplies closer views anchored by a fixed master setup of the parlor.

When Leland Palmer comes in to say that his wife has had another vision, and when Sarah rises to describe it, we get a long-lens framing, presumably from the B camera aligned with the camera that supplied the master framing.

Sarah’s last gesture in the shot involves extending her palm and recounting her vision of a hand taking out a necklace from under a rock. This strikes Donna with particular force, because she and James have hidden Laura’s necklace the night before. The scene ends with a cut from Sarah to a framing of Donna like that at the end of the first shot. We track in on Donna as she turns away, and the scene ends.

Hunter has talked about getting ideas for this episode from watching Preminger’s Fallen Angel, which handles action in rather confined sets. The wild wall that puts Hunter’s camera behind the sofa allows him to emphasize the proximity of all the characters. Moreover, in this final framing, we can see one virtue of staging the scene for both the static establishing shot and the moving master. In the final moments, Sarah’s gesture can be seen, out of focus, behind Donna and on the frame edge. The surface action of the scene—Truman’s investigation, Sarah’s visions—is counterweighted by the covert action, Donna’s determination to solve the mystery herself.

Stylistic Peaks

Talking with a class in media production, Hunter remarked that story premises—the arresting or puzzling first few scenes—are fairly easy to invent. “Endings are hard.” He stressed that a good story needs a strong climax and resolution. Novels and short stories tolerate diminuendos and offhand closings, but movies need gripping wrapups. Adapting a piece of fiction, Hunter pointed out, may require you to “amp up dramatic tension for a climax.”

As he spoke, I thought about another of his contributions to Twin Peaks, the crucial episode (number 16) in which Leland Palmer, inhabited by Killer Bob, is seized and flung into a holding cell. There Bob-in-Leland rages, seethes, chatters, and laughs demonically. But once Bob abandons him, Leland collapses in agony as he confronts the fact that he has killed his daughter. As if this weren’t dramatic enough, it takes place during a deluge from the building’s fire sprinklers, set off by a cigarette in another room.

Hunter’s direction shows how stark imagery can enhance the actors’ performances. A kind of cleansing spray pours down on Palmer as he confesses, sobbing. Agent Cooper, the Dream Detective, holds him as if cradling a child. There are only four primary setups over about four minutes.

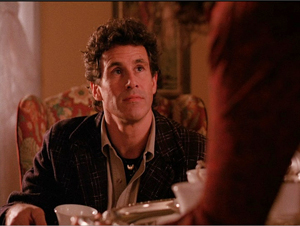

Instead of cutting quickly, Hunter lets the shots play out to emphasize the dialogue and especially the performances: Ray Wise as Leland, terrified that he may be damned, and Kyle MacLachlan as Cooper, whose daffy mysticism finds its reason for being as he guides the dying murderer “toward the light” and a reunion with his dead Laura (top of this section). The scene’s intensity is shaded by the perverse erotic overtones of Leland/Bob’s unholy passion for young girls and the moment when Leland, recalling being seduced by Bob, moans, “He came inside me.”

Minnelli, who set the climax of Some Came Running in a luminous carnival and in The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse gave us the image of a man gripping his father in a soaking thunderstorm (above), might well have admired Hunter’s handling. It’s at once tactful (letting the actors act) and flamboyant (the shadows, the torrent of water). In Hunter’s hands Twin Peaks’ New Age quirkiness is cast off and the climax plunges us into pure, traumatic melodrama.

Meaning in the madness

Hunter shot River’s Edge in thirty days at a cost of $1.7 million. Built around Crispin Glover (suddenly hot after Back to the Future) and featuring the young Keanu Reeves and Ione Skye Leitch, it had early buzz. But it alienated the industry. Variety‘s 1986 Montreal festival review called it “an unusually downbeat and depressing youth pic.” By odd coincidence, that review ran alongside a review of Blue Velvet (“a must for buffs and seekers of the latest hot thing”), and both films were shot by Frederick Elmes.

“None of my features made any money,” Hunter says today. But River’s Edge has become a classic of 1980s independent cinema, an anti-John-Hughes teenpic and a sobering look at how kids really live.

Its unglamorized treatment of high-school sex and drugs goes along with a bleak but nonjudgmental account of a moral blank at the center of kids’ lives. A young man has strangled his girlfriend Jamie, and he takes his pals out to see the body, twice. At first none of them reports the crime, and one, the perpetually hyper Layne, urges everyone to keep quiet. Two in the posse have qualms. Clarissa considers calling the police, and Matt in fact does. In the course of a day, a night, and the following day–a sort of grunge-and-amphetamine American Graffiti time frame—the kids circulate through their neighborhoods settling scores and responding to the threat of an investigation. The one adult in sync with the kids is Feck, a former biker and now drug dealer, who claims to have killed a woman years before.

At first glance the film looks wholly moralizing, with a 60s-era teacher trying to stir his class to political consciousness and a hardened cop squeezing Matt to admit something, anything about the crime. The stoned indifference of the kids to the murder of one of their friends–they don’t cry at her funeral–would seem to indict them as hopeless. But the adults driven to exasperation are hardly role models. The teacher is self-righteous, the cop bullying. Matt’s mother and her live-in boyfriend seem as concerned for their own lives, and their cache of weed, as they are for the kids. And the future? Tim, Matt’s little brother, is the first to spot the body but shrugs it off, and he wantonly drowns his sister’s doll. Eventually Tim will try to kill Matt.

Again, Feck sort of understands. His own drug-driven mania enables him to identify with the kids to whom he gives pot for free. But even he is startled by the hollowness of their lives. He confesses a despairing love for the woman he killed, but he sees no depth in the boy Samson, who strangled Jamie “because she was talking shit.” Feck’s madness is born of passion, Samson’s of annoyance and indifference (“She was all right”). Most of the men treat women, whom Layne calls “evil,” as disposable, and the motif of the dead girl–Jamie, the sister’s doll, and Feck’s inflatable sex doll–brings out the parallels between three generations. This is as bleak a vision of American life as we’ve had in contemporary cinema, and the kids’ amorality, festering in an old foothill community, can’t even be blamed on suburbia.

My friend JJ Murphy has written a superb analysis of River’s Edge, with attention to the craft of Neal Jimenez’s script. Here I want just to show how Hunter, working with more elbow room than in the TV projects, enriches his plot with a tightly shaped, classical style. Two scenes–not climaxes–will help me.

Matt’s brother Tim is playing a video game in the Stop-Go, and the clerk is dimly visible at the counter behind him. Then Samson enters in the background. This concise framing is the scene’s establishing shot, introducing all three of the scene’s characters.

One maxim of filmmaking is: Who is the scene’s anchoring character? Through whose awareness is the viewer experiencing the action? Here, it’s Tim. As Samson goes to the cooler and snaps out a can of beer, Tim watches as he lumbers down the aisle to the front counter.

Samson confronts the clerk, who asks for his identification. He refuses to give it and a quarrel starts, observed by Tim.

Now Hunter uses another classical technique. Like Hitchcock, he gives us something to listen to and something different to watch. As the quarrel at the counter grows more heated offscreen, we see Tim slip to the cooler and swipe two beers.

Actually, Hunter doesn’t show us a close-up of the beers, as we might expect. We see only Tim fumbling and his coat getting baggier. But we know he’s stealing, partly because he checks the security mirror.

Tim makes his way to the front of the store and steps out while the quarrel continues. This introduces a level of suspense, while also characterizing Tim as already a practiced shoplifter.

After a tug-of-war over the beer can, Samson angrily relents and makes his way out. In the parking lot Tim disappears and then reappears, perched on the hood of Samson’s car. The initial front-counter framing has “primed” Samson’s car as an innocuous part of the background in the earlier shot, so that it can be used now. Deep-space staging allows you to quietly set up elements to be activated later in the scene.

Samson leaves the shop scowling and goes to the driver’s seat, where he bends down as if seeing something.

Tidiness: Now we know that Tim’s momentary absence took place because he slipped the beers into Samson’s car. Hunter could have cut in a close view of two beer cans left on the seat, but instead he sustains the shot and lets us see Samson bring one into view, open it, and take a big swig. The beer swiping becomes no big deal, nothing out of the ordinary (as a close-up would have hinted). This sort of swift, small-scale flow of information keeps us waiting for more developments. Those come when Tim peers into the window and says, “Don’t mention it.” He adds, “I saw you this morning.” Samson: “Yeah?” Pause. Tim: “Got any dope?”

The whole scene establishes the tribal amorality and cohesion of the young crew. Tim takes the murder in stride. He swipes the beer not just to do a good turn to his brother’s friend but also in hope of scoring weed.

Samson is at first unresponsive but then, as if to acknowledge he owes the kid, tells him to get in. Tim loads his bike into the back seat. They will go see Feck.

This is the first time we’ve seen the exterior of the Stop-Go. Another film would have given us the conventional establishing gesture, a shot of the front, sign and all, as John pulled up. But in the interests of economy and forging an attachment to Tim, I think, the film starts the scene inside and gives us the exterior only when we need to see it, along with the physical action of loading the bike. Later, we’ll see the Stop-Go from comparable angles and we’ll be able to reorient ourselves.

The use of depth, the careful timing of character movements through the frame, and the overall economy of the sequence stand in contrast to the more heavily cut string of singles we get in “Perception” and even in the Twin Peaks episodes. Comparatively few setups are repeated. There’s no standard shot/ reverse-shot, and no over-the-shoulders. (Imagine how a conventional TV director would have cut up the confrontation with the clerk.) Hunter has constructed his eleven shots so that each one presents a compact body of information, and the shots interlock neatly.

The same conciseness and flexible use of depth can be seen when we return to the Stop-Go during the night scenes. Again, there’s no exterior establishing shot. Matt has come to buy beer at the shop, and there Samson and Feck find him. Hunter could have used the earlier counter setup to save time in shooting, but he recalibrates. A judicious over-the-shoulder framing kicks off this four-shot scene.

Matt is trying to buy a six-pack after hours, and the same blue-vested clerk forbids him. A reverse angle shows Samson coming in, followed by Feck with his sex doll Ellie.

After telling Matt to take the beer, Samson pulls Feck’s revolver. Matt is stunned. In the background, out of focus, Feck is making his way to the cooler.

At Samson’s insistence, Matt grabs the beer (and pays for it). As he edges out of the shot, rack focus to Feck turning to ask the clerk: “Do you have Bud in bottles?” End of scene.

Same setting as the first scene above, and something like the same trigger for conflict: the kids want beer, against the rules. And we have the same geography/ geometry, with the scene organized around the beer cooler, the counter, and the aisle between them. But Hunter has activated the space in a significantly different way. With a close shot he stresses Samson at the moment when he pulls the revolver, and he pays the scene off on a semi-comic note that doesn’t underplay Samson’s casual sociopathy.

The long lenses, the marked rack-focus, and other techniques are more characteristic of post-1960 filmmaking than of the studio years. But the demand for concise visual storytelling, layered with echoes of earlier character gestures, recasting previous dialogues and conflicts through new angles and cutting patterns–these are time-honored strategies. Hunter, like many another movie brat, learned the lessons of classical Hollywood moviemaking. Even in scenes of fairly low dramatic pressure like these, he shows the flexibility and richness of that tradition when it’s put to new uses.

Thanks to Tim Hunter for coming to Madison, Jim Healy for arranging the visit, Eric Hoyt for letting me sit in on his class, and Roch Gersbach for all his assistance.

The Mad Men mystique is engagingly chronicled in Matt Zoller Seitz’s columns in New York Magazine.

The best accounts of television aesthetics are those by Jeremy Butler: Television Style (Routledge, 2010) and Television: Critical Methods and Applications (4th ed., Routledge, 2012).

The review of River’s Edge can be found in Variety (3 Sept. 1986), p. 16. For a little anticipatory buzz, see “Sanford-Pillsbury Readying Pic on Teen Murder for Fall Release,” Variety (2 July 1986), p. 27. Roger Ebert’s review captures the wider response to the film at the time, adding: “This is the best analytical film about a crime since The Onion Field and In Cold Blood.”

Why don’t I write about television more often? The answer is here. For more on how post-1960 directors continued the classic studio tradition, see The Way Hollywood Tells It.

Dennis Hopper as Feck in River’s Edge.

Return to Paranormalcy

Paranormal Activity (2007).

DB here:

What is there for me to do? Art historian Ernst Gombrich suggested that this is a problem that confronts every creative artist. If you want to make paintings or compose music or direct movies, you confront an existing community of artists and long-established traditions of art-making. You work with what you’re given. You inherit technology and materials, but you also inherit ideas and familiar conventions and well-worn work habits. You want to find a niche, but you’re also in competition with others for it.

You confront, in other words, a kind of ecosystem with its own history and a current state of play. How can you fit your talents and temperament into that ecosystem? How, more specifically, can you create something different?

Variorum moviemaking

Paranormal Activity (2007).

It can be useful to think of commercial filmmaking as this sort of system, a cooperative/ competitive arena challenging directors, writers, cinematographers, and other film artists to innovate. Innovation isn’t the only aim of moviemaking, of course, and just because something is innovative doesn’t mean it’s good. And not all innovations announce the fact; Jean Renoir’s deft uses of space in his 1930s films didn’t trumpet their originality. Innovation can be quiet and subtle.

Still, as students of the art of film, we’re naturally attuned to novelty—a fresh treatment of an established genre, an unusual approach to characterization, a new application of existing technology. If we’re interested in mainstream film, particularly Hollywood’s, we learn things from the way that filmmakers swarm over something new and try to mimic it or tweak it or turn it around. Make a movie about a possessed pre-adolescent girl who needs an exorcism, and soon we’ll have movies about possessed high-school girls, possessed dogs, possessed cars, and so on.

Call it the variorum quality of popular culture—the tendency to explore, sometimes exhaustively, all the possibilities of a single premise. Filmmakers seize an idea and run with it, in different directions. Of course they may be asking, “How can we cash in on this trend?” but in order to answer that they have to ask another question: “What if we did such-and-such differently?” Even if you start by trying to make money, you still have to make a movie. And that movie will need to be minimally distinctive. The question for the filmmaker remains: What is there for me to do?

Something like this process is going on under our noses. Paranormal Activity (2007), Paranormal Activity 2 (2010), Paranormal Activity 3 (2011), and Paranormal Activity 4 (2012, released in October) have become a cheaply made but very successful franchise. Taken together, the four films have won estimated worldwide box-office revenues of $700 million and counting.

Their popularity offers one reason to examine them, but a better reason is that they make the variorum dynamic unusually clear. The originator and director of the first installment, Oren Peli, and the directors who followed (Tod Williams for the second entry, Henry Joost and Ariel Schulman for the last two, along with continuing writer Christopher Landon) were obliged to innovate within very tight limits. From movie to movie, they came up with fresh and unexpected solutions.

This isn’t about proving these movies to be masterpieces or stinkers. Whatever you think about the quality of the innovations I’ll be looking at, they offer us some leads about how filmic storytelling can change under the “selection pressures” of American commercial cinema.

More strikingly, the Paranormal Activity franchise is that rare thing: a popular series that stands out by very specific and noticeable uses of film technique. Audiences eat it up. The suspense and surprises are part of the appeal, certainly, but there’s reason to think that at least some viewers look forward to following each entry’s formal dynamic of familiarity and variation. Filmmaking becomes a kind of gamelike performance that coaxes us to ask: How will they deal the cards this time?

Of course there are spoilers from here on. Even the pictures contain spoilers.

The same, please, only different

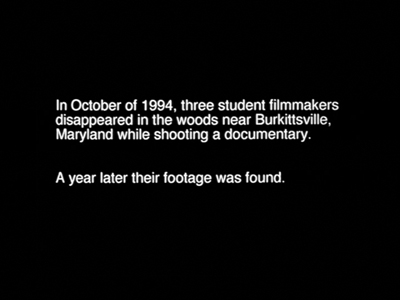

The Blair Witch Project (1999).

The broad task that Peli faced when he began work on Paranormal Activity was clear: How to make a diabolic-possession film different from the others? By then, and still, that variant of horror was pretty well-defined. And indeed the film Peli came up with wasn’t that original in outline. A couple is disturbed by mysterious noises and actions in their house. They call in experts and try to find the source of the disturbance. Eventually the woman becomes possessed and kills her lover.

Throughout, the conventions of the supernatural film rule: sudden blackouts, bone-shaking noises emitted by offscreen fiends, and characters exploring basements, closets, moonlit yards, and other scary spaces. Special effects are invoked to levitate victims or drag them by unseen hands. Occasionally we’re faked out by scares launched as pranks that some characters pull on others. As usual, normal, i.e. bourgeois American life, is devastated by supernatural forces. Cozy domestic surroundings, including an array of consumer goods, become menacing. Much of all this was pioneered by The Exorcist (1973), so the tradition has plenty of cobwebs on it.

Shooting in seven days on a small budget, Peli settled on a formal framework that borrowed from another tradition, that of the pseudo-documentary fiction film. This too goes far back, to This Is Spinal Tap (1984) and Bob Roberts (1992), and before to Stanton Kaye’s Georg (1964), Jim McBride’s David Holzman’s Diary (1967), and Mitchell Block’s No Lies (1972) , and Peter Watkins’ Culloden (1964) and The War Game (1965). More distant predecessors might be Welles’ 1938 War of the Worlds radio broadcast, or even the fake memoirs we find in the early years of the novel. Today the pseudo-documentary mode, used for comic or dramatic purposes, is familiar to us from television shows like The Office. This mode has its own conventions, such as to-camera interviews and the occasionally awkward framing, most noticeable in the recurring image of a fallen camera.

The pseudo-documentary approach had been tried in the horror film in the 1980s, but it gained attention at the end of the 1990s with The Last Broadcast (1998) and The Blair Witch Project (1999). No surprise: Horror films tend to be low-budget items, and shooting in a run-and-gun manner, with handheld shots and awkward sound, was both cheap and realistic-looking. A cycle emerged, exemplified most notably in the bigger-budget Cloverfield (2008).

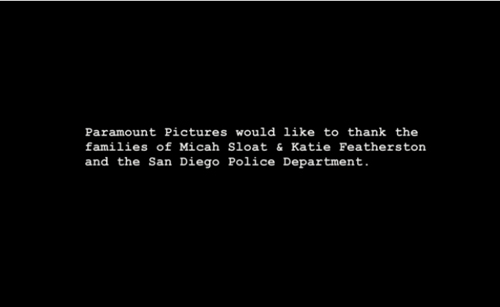

The problem of the pseudo-documentary is to motivate the fact that someone is filming these dramas. Various solutions have been worked out. You might make the protagonist a filmmaker exploring a subject or creating a diary. Or you can pretend that the people being filmed are celebrities (as in Spinal Tap). Or make the act of filming an effort to document dramatic occurrences. Filmmakers face a second problem as well: motivating how the film has been made public. You can, for instance, present it as a TV or theatrical documentary, as Spinal Tap purports to be. More recently another solution has been found. You can suggest that this film has been discovered after the events were over.

Because of this rationale, the approach is sometimes called the “found-footage” treatment, or in Varietyese the “faux found-footage film.” I’m not delighted by this term because for a long time “found-footage” has referred to films like Bruce Conner’s A Movie or Christian Marclay’s The Clock, assembled out of existing footage scavenged from different sources. So I’ll call fictional movies like Blair Witch and Cloverfield “discovered footage” films.

One reason for this name is that these films hark back to an early tradition of literary fiction, that of the “topos of the discovered manuscript” or “the old oak chest.” Here a tale is presented as a manuscript found and prepared for publication by other hands. The purpose, at first blush, is to give the story an air of authenticity. The same urge prevails in the discovered-footage horror movies, which use this blatant artifice to play with the possibility that these weird happenings really took place. As the image surmounting this blog entry suggests, Peli linked his film to this tradition, even letting the all-too-real company Paramount Pictures attest to the veracity of what we’re going to see.

The development of the Paranormal series took place under the sign of rivalry. A great many horror films of the late 2000s and early 2010s used the pseudo-documentary approach, sometimes marking the footage as recovered. After the success of Peli’s original film, intense competition emerged. There was a blatant ripoff (Paranormal Entity, 2009), followed by many others, including the subtler pseudo-doc The Last Exorcism (2010), which seems to presume that we’ll take it as a found-footage item too.

Just as important, in making successors to the original film, Peli and his colleagues had to compete with themselves. So they freshened up their plots. Paranormal 2 features not a live-in couple but a family; Paranormal 3 centers on an unmarried mother, her live-in boyfriend, and her two daughters. Paranormal 4 features a family whose neighbors are a possessed mother and son.

Interestingly, the subsequent films supply relatively little mythical or doctrinal backstory. Although there are always one or two scenes in which the characters launch on some research, the plots mostly minimize exposition about the hows and whys of possession. (Contrast The Exorcist.) We get just enough hints to assume that there’s a demon who offers women worldly goods in exchange for innocent boys’ souls. Mostly the films concentrate on the characters’ responses, chiefly their quarrels about whether the weird happenings are supernaturally caused. Each film needs at least one blocking character, somebody whose skepticism, obstinacy, or cluelessness keeps the plot going and prevents the characters from simply getting the hell out.

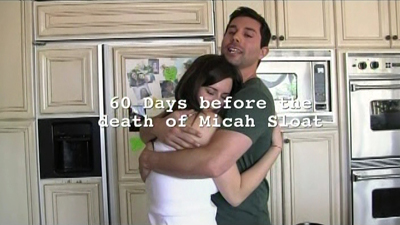

The films also vary protagonists and the characters we’re attached to. Micah moves the plot forward in the first entry with his urge to document the weird happenings, while in the second, the father Daniel and his daughter Ali take turns probing what’s going on. In the third film, again it’s mostly a male filmmaker, Dennis, who propels the inquiry, while in the latest iteration, the narrative momentum is passed to the inquisitive teenage girl Alex.

Perhaps the most up- to-date way the filmmakers refresh the franchise is by making the various films interlock. The films set up a chronology that positions the original release as the third phase of a larger action. Paranormal 2 occurs just before the events of the first one, and Paranormal 3 flashes back eighteen years to supply some preconditions for the previous entries. Moreover, some portions of the plots overlap, so that scenes from one installment are replayed in another, explaining how the time frames mesh. This sort of shuffling with time and perspective is nowadays common both within films and across them; the second and third Bourne films offer good examples.

Above all, the filmmakers have created a new ecological niche by virtue of some initial stylistic choices Peli’s first film made. They were striking but exceptionally constraining. To produce more Paranormal films created a very specific set of problems: How to respect those initial constraints and yet rework them in unpredictable ways?

Hand-eye coordination

Paranormal Activity 3 (2011).

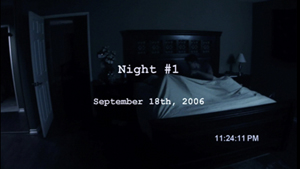

Cloverfield and The Blair Witch Project use the discovered-footage format to justify their amateurish look. These are on-the-fly records of some pretty strange phenomena. By contrast, the Paranormal Activity series doesn’t limit itself to handheld footage. It sets up a dynamic between that and something quite different: the fixed, distant shot reminiscent of surveillance footage.

The alternatives are laid out in the first film, when Micah, perplexed by the ghostly goings-on, buys a fancy video camera and sets it up in the bedroom he shares with Katie. That way he can capture what’s happening while they are sleeping. At other times he takes the camera off its tripod and shoots the house in the usual handheld, eyewitness way.

The result is a movie, and a series, with two markedly different visual treatments. The handheld footage is pure subjectivity, showing exactly what the camera operator sees. It responds immediately to what’s out there, panning or moving toward things of interest. It also permits fairly close shots of the other characters. By contrast, the locked-down shots are completely objective, recording in the manner of surveillance video. Indifferent to human intentions, the camera may be poorly placed to capture what’s happening. And it’s by and large committed to very wide and distant views, compared to the closer views yielded by the probing handheld lens.

Take the handheld technique first. This yields a severely restricted range of knowledge, as I’ve already discussed in relation to Cloverfield. This narrow range is suited for a film playing up mystery and suspense. In any given scene, we don’t know any more than the camera operator does. But of course this feature is also a drawback, because the filmmaker can’t build suspense through crosscutting—showing, say, a door creaking or a shadow moving somewhere else in the house.

The default for most fiction films is camera ubiquity. That is, in principle the camera can be anywhere and show us anything. If the camera doesn’t do that, you need special justification. So for thrillers or horror films, you can show just advancing feet or clutching hands or scary shadows, because we know that these genres promote gaps in our knowledge. We accept the obvious suppression of information.

Another way to justify not showing everything is attachment to one character’s range of knowledge. This is another common strategy of suspense and horror. Even more restrictive is an optical point-of-view treatment, which might be the polar opposite of camera ubiquity. Hitchcock was particularly keen to find ways he could drill into optical point-of-view as a narrative device.

Treating the camera as a vehicle for subjective POV can yield some sudden shocks. One of the most provocative ones in the Paranormal franchise occurs in the third installment, when Dennis approaches Julia at the top of the stairs. His camera-eye viewpoint makes her seem to be standing there, but as he approaches the perspective changes and we see that she’s actually floating.

In the same installment, the “Bloody Mary” encounter in the bathroom gains force not only through the camera’s limitation to Randy’s optical pov, but through the mirror that in the darkness reflects only the red dot of the camera’s “on” signal. It’s all we have to look at in a scene in which the sounds of thrashing and smashing overwhelm the image.

So the handheld subjective camera of Paranormal Activity and other films in the trend avoids camera ubiquity. This creates familiar problems, but filmmakers in this stylistic cycle have come up with solutions.

*How do you explain why the camera is recording this drama? The standard justification is that a crew has decided for some reason to make a movie about something, as in Spinal Tap and The Last Exorcism. Paranormal Activity finds two more pretexts. The video camera can record home movies in Daddy-cam fashion; this motivation is especially important in Paranormal Activity 2. Or the camera can serve to document the weird goings-on in the demon-haunted homes. This motivation is especially strong for the locked-down surveillance recordings.

The camera operator may be the protagonist or at least a major character. How do you show the character to the audience? Options: Have him or her shoot the act of filming in a mirror (very popular). Have him or her address the camera when it’s resting. Let other characters wield the camera and show the cameraperson. Or set the camera down and let it keep filming, often risking decentered compositions but still indicating things clearly enough.

Sometimes you want camera ubiquity. Shot/ reverse-shot cutting is especially valuable because it can emphasize major lines of dialogue and reactions. How can you achieve this in the subjective-camera style? By cheating a little. For example, a single-camera record can capture the give-and-take of a conversation only by either framing both people in a single shot or by panning between them. If you want proper shot/ reverse-shot cuts you have to use overlapping sound during editing to cover the moments when you stopped the shot or panned to reframe the other character. Even when you establish that two cameras are filming the action, you may have to cheat on position quite a bit. (See this discussion of a scene in The Office.)

Chronicle offers an intriguing example of how these problems can be solved. At the beginning Andrew, shooting into a mirror, explains that he has decided to film everything.

Throughout the early portions of the movie we get only what his camera sees, usually with him behind the viewfinder. But eventually we meet Casey, a young woman who has a camera too. The result is shot/ reverse-shot cutting justified as each camera’s viewpoint.

At the climax, when the boy superheroes fight it out above the city, so many people are filming the scene with cellphones, TV news cameras, and government surveillance, that the action is covered fully from many angles. The visual storytelling achieves camera ubiquity.

The impersonal view

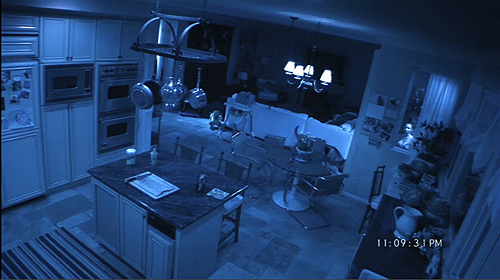

Paranormal Activity 2 (2010).

Many horror films have used the handheld approach, but the strongest innovation of the Paranormal series, I think, is the idea of counterweighting the free-camera shots with fixed-camera footage. Like the moving handheld shot, the locked-down surveillance shots avoid camera ubiquity and restrict us severely. But they have other advantages.

As we’ve seen, the fixed setup complements the human-centered handheld camera. It shows everything in front of it indiscriminately. By prying itself loose from the characters, and filming them while they’re not aware of it—especially when they’re sleeping—it allows us a more neutral sense of the film’s space and the things that happen in it. Just as important, it fits smoothly with some standard horror conventions.

For example, offscreen threats are central to the horror film, and the fixed camera can maintain their effects. As (bad) luck would have it, the cameras set up in Paranormal Activity aren’t always ideally framed for showing everything. Very often they merely suggest the demon’s pursuit of the characters. The demon Toby is just off left of frame in the third installment (he blasts some air at the babysitter Lisa) and some entity like Toby seems to be at work offscreen right in the second one, attracting Hunter’s attention.

Likewise, offscreen sound is crucial to the horror film, as Val Lewton and Jacques Tourneur showed long ago with the sudden intrusion of bus brakes into a suspenseful pursuit in The Cat People. The fixed camera can capture those sounds but because no human agent is behind it, there’s no way it can move forward to explore their sources, as a camera operated by a human might.

The surveillance shots, while limited visually, provide information that the subjective shots don’t. In the first film, while Micah sleeps, the bedroom-cam shows some weird goings-ons that he isn’t aware of—notably, Katie getting up and standing unmoving by the bed for several hours. In later installments, the presence of more than one surveillance camera can provide story information via crosscutting. As with Chronicle, multiplying surveillance views pushes the visual narration toward a more complete (and conventional) coverage of the action.

Crucial to the films’ innovation is the fact that the locked-down shots are distant views. The films have extraordinarily few shots for contemporary productions: about 230 in the first part, about 500 in the second (because of the multiple cameras), about 230 again in part three, and about 320 in the last. The number of setups is greater than these figures would suggest because some cuts are jump cuts or drop-frames within extended camera takes.

Long-take, locked-down shots are common in “festival cinema” but virtually unheard of in mainstream Hollywood film. Remarkably, we have box-office hits consisting of long, static takes that hold multiplex audiences in thrall. Of course the long “empty” takes are recruited to the conventional cause of sustained silence and sudden, startling outbursts. The genre, we might say, motivates the style. The same audience wouldn’t be so tolerant of a protracted shot in Tarkovsky or Hou.

Yet we shouldn’t dismiss these shots as mere gimmicks. Their stillness encourages us to scan these spacious frames for hints about what will happen next. The impersonal lens often lingers on bare spaces, and when something of interest happens we won’t be given a cut in. Sometimes the crucial action is barely there, as when Ali and Brad are hidden in shadow, behind the digital read-out, in the lower right of this shot.

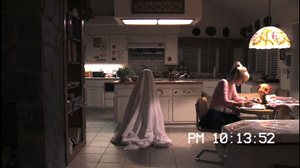

To some extent, the distant framing of the surveillance shots revives classic staging techniques in a cinema that seems largely to have forgotten them. Instead of the barrage of close-ups and rapid shot changes we get with today’s intensified continuity style, we get lengthy, static, often indiscernible images we have to scour for clues.

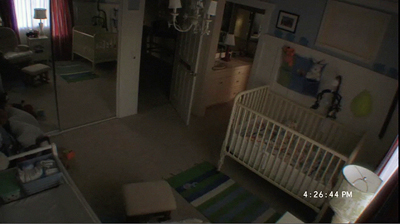

Granted, often those clues are signaled through slight movements, as in the eerie twirling of the toy spider suspended over Hunter’s crib (top of this section). Centering is also important, as when the Ouija board’s planchette scuttles around and then bursts into flames. Sometimes a character can point to what’s important in the visual field.

For the most part, the static framings yield deep, dense compositions reminiscent of 1910s tableau cinema. In the second installment particularly, key bits of action are pushed very far from us or isolated in apertures. The kitchen camera setup lets Ali’s distant face poke up from the sofa into bare visibility (immediately below), or be framed in the window when she tries to get back in as Abby the dog approaches the locked door. (See bottom of this entry.) Unlike most modern films, these lose a great deal of information on small screens.

Overall, the handheld POV shot and the detached and distant long shot complement each other. Both are well fitted to the demands of the horror film, which requires secrets to be concealed from the characters while throwing out hints to us. Beyond genre conventions, though, these films might train the young audience to be patient and learn to settle into images that ripen slowly and don’t yield their meanings up immediately. Well, I can dream, can’t I?

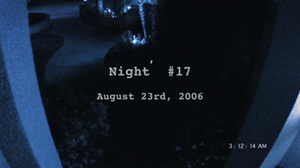

Stretching the rules

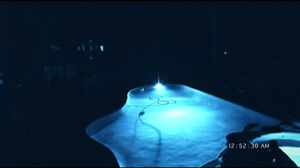

Paranormal Activity 2 (2010).

I’ve spoken of these films in general terms, but what makes the series particularly intriguing to me is the development from one installment to the next. The makers aren’t only competing with other filmmakers; they’re competing with themselves. Each new episode has to innovate within the framework they’ve set up—not only by expanding the story action, as we’ve seen, but also by varying the stylistic parameters. That generates new problems, self-imposed ones, and the search for new solutions.

The original Paranormal Activity sets up many of the stylistic premises of the series: the use of mirrors to introduce the camera and its operator, the idea that the investigator will replay the locked-down footage (and then film that with the handheld camera), and the need for at least one skeptical character who will resist the investigation. Here Micah has one camera, which he carries with him by day and installs on its tripod at night. And the resolution of the film is played directly to the camera, as Micah slips out at night to follow Katie and after a long pause is hurled back into the camera, smashing it to the floor. The tipped-over framing records Katie creeping forward, smiling, and roaring into the lens—her revenge on the filming she hated from the start.

Paranormal Activity 2 is largely a prequel, taking place about a year before the first one. Now the single camera is a daddy-cam, recording the arrival of Hunter, the baby born to Daniel and Katie’s sister Kristi. This camera is really a daughter-cam, because it’s mostly wielded by Ali, Daniel’s daughter by a previous marriage. She drives the investigation, but she’s initially more thrilled than afraid. (She also wonders if the ghost is her mother.) The situation shifts from a live-in couple (Paranormal 1) to a happy nuclear family (Paranormal 2) and from a midrange income level to a very prosperous one.

After the house is mysteriously ransacked, Daniel installs a home surveillance system. Six high-angle cameras cover the house. They’re trained on the front door, the back pool, the kitchen, the living room, Hunter’s room, and the master bedroom. In addition, we have Daniel’s Daddy-cam, now outfitted with night vision. This will become important in the climax, allowing us to glimpse, spasmodically, the demon’s response to the attempted exorcism of Kristi.

Naturally all these cameras yield a much-expanded range of knowledge. Now we can see at least part of what’s going on in various parts of the house, and the narration cuts freely from one room to another. Because of the shot scale, though, quicker cutting means that we have to run fast checks in each shot on whether anything seems dangerous.

Important shifts toward camera ubiquity, these new setups also can play a game with our expectations. For example, the eerie shots of the swimming pool at night show the bobbing pool cleaner sidling through the water. Yet Kristi points out that every morning the cleaner has been removed from the pool. The surveillance shots we see never show this, and not until late in the film, when other stretches of the surveillance footage are played, do we see it leave the water. Even sneakier is the tendency of the night footage to mislead us about what’s important. Nearly every night sequence begins with a shot showing the front stoop of the house, but nothing (so far as I can tell) is ever revealed by these images in Paranormal 2, though at the start of Paranormal 4 they pay off by showing Katie leaving with Hunter in her arms.

In context, Paranormal 2‘s recurring shot serves to announce a new sequence of hauntings, but it’s also a little amusing. The standard shot showing a safe household, with no one approaching, serves simply to remind us that the demon is already comfortably inside.

Paranormal Activity 3 is a more distant prequel, setting up the childhood of sisters Kristi and Katie. Here the novelty is the use of VHS tape to record the action. Again, the footage begins as Daddy-cam shooting, as Dennis films Katie’s eighth birthday party and then starts to make a sex tape with Julie. But when the spooky hijinks start, the man of the household decides to investigate. Unlike Micah, though, Dennis is a videographer by trade and so has three cameras at his disposal. He uses one as a handheld device, occasionally set up in his and Julie’s bedroom. He installs another camera in the girls’ bedroom and puts the third one downstairs.

Reducing the “panopticon” of the previous installment from seven to three might be seen as a step backward, but the filmmakers have a clever innovation up their sleeve. Dennis can’t cover the downstairs adequately with his remaining camera. Out of a table fan he constructs a swiveling base to which he can attach a camera. This yields a panning back-and-forth framing.

Of course this mechanical panning is just as little concerned with items of human interest as the static shots of the earlier installments. Indeed, it maintains the horror-film convention of ominous offscreen action, but motivates it as impersonal scanning. The camera slowly reveals pieces of space, but if something exciting starts to happen onscreen, the camera relentlessly turns away.

Set in 2011, Paranormal Activity 4 is the first chronological sequel to the first entry, with a new cast of characters involved in action long after the initial demon outbreak. In some ways, making a teenage girl the protagonist is more conventional than the early films’ focus on couples. Still competing with themselves, the filmmakers needed to recast the series’ stylistic premises. They seem to have asked: Well, who uses dedicated video cameras today—especially if our characters are mostly teenagers? Accordingly, the franchise’s signature seesawing between handheld imagery and locked-down recording is now provided by cellphones and computers.

Although some footage purports to come from a video camera, most of it doesn’t. Alex and her boyfriend Ben set up four laptops around the house, all constantly recording what transpires in the rooms. This tactic allows some changes in the surveillance footage. The camera angle is typically lower than in Paranormal 2, since the laptops are sitting on tables or counters. Moreover, their framings can shift. In the boy Wyatt’s room, his laptop is sometimes closer or farther away, and is sometimes blocked by masses of blankets. The kitchen laptop is shifted around when Alex’s mother moves it closer to her work area.

In addition to recording the household’s supernatural doings, the laptop device lets the teenage heroine Alex have video chats with her boyfriend Ben. In the earlier films we get occasional to-camera monologues, but here we watch Alex talk close to the lens, directly to us, and at length; we see what Ben sees, and sometimes we see him from her screen’s vantage–a sort of virtual shot/ reverse-shot.

At crucial moments Alex picks up the laptop and carries it around with her. As a result, we get more conventional horror-film images of the protagonist—ideally an easily startled young woman—moving through space. In the earlier films, the camera operator’s reactions were given through the subjective framing and offscreen comments, curses, and yelps. Now when Alex hurries across the street to Robbie’s mystery house, we see principally her face.

Ariel Schulman acknowledged that the laptop device adheres to the “rules” of the franchise and the genre while producing, for the first time, conventional close shots of the camera operator. “We were really psyched just to do a shot where the girl’s carrying a laptop, and it’s just filming her. . . It just seemed like a really fun way to carry a camera and film ourself because otherwise there’s no other way to shoot close-ups in a ‘Paranormal’ movie.” Henry Joost adds: “The close-up on a teenaged girl’s face being scared is a horror movie icon. . . . If it’s dark, the only light is from the laptop screen, which is scary. It has all the right ingredients to be in a horror movie.”

Finally, in an innovation parallel to the night-vision footage of part two and the swiveling camera of part three, Paranormal Activity 4 incorporates Xbox Kinect technology. The gadget projects a blast of green dots into the living room, and these can be picked up by night-vision video. One effect is to make Robbie even more ghoulish.

Consistent with the perceptual teasing in earlier films’ extreme long-shots, the Kinect grid also signals the demon’s presence by slight contours, most jolting when the dots shift a little to betray phantom movement. As the earlier entries used powder or dust to track the invisible demon, Paranormal 4 enlists a higher-tech sort of particle. Like the other innovations, it shows that the creators needed not only new situations and plot twists but new variants on their stylistic premises.

Who’s there?

I haven’t yet mentioned one creative problem discovered-footage filmmakers need to confront. Who’s responsible for what we see?

The Paranormal films are obviously assembled. They often have superimposed titles, as above and at the start of the night hauntings. The very first one, at the top of this entry, suggests that something dire will happen to our protagonists; otherwise why ask the families for permission to show the footage?

Editing and camera tricks show the hand of some coordinating intelligence. Some scenes fade out and the night scenes typically start with a fade-in. Locked-down scenes consuming hours are sometimes run fast-forward. We even get dialogue hooks. Randy says, “Just watch the fuckin’ tape, Dennis.” Cut to Dennis watching the tape. In the multiple-camera entries like 2 and 3, there’s cutting from room to room, sometimes following characters through the house. There’s also crosscutting for traditional suspense effects, as when Julie and Dennis are quarrelling while Katie is terrorized by Toby upstairs.

The multiple-camera films betray some perverse humor. We cut from the babysitter Lisa’s terrified retreat from the girls’ room to a shot, about an hour later, of her waiting anxiously by the door for the parents’ return so she can get out as fast as possible.

And sometimes the series of shots is deliberately misleading, dwelling on vacant spaces and failing us to show the characters doing crucial things. Some agent who wanted to convey basic information would provide a more concise set of extracts. This assembler wants to build suspense.

Cloverfield presents itself as a government file, presumably collected and joined by analysts. But Chronicle and The Last Exorcism don’t bother to explain how the recovered footage was discovered, let alone assembled. It’s as if, by this point in the development of the cycle, these marks of authenticity can be omitted.

As usual, the Paranormal series is a bit cagier. With opening titles indicating that the footage is in official hands, the films suggest that these too are from an ongoing investigation of Katie and her family. But I wouldn’t put it past some future installment to center on the unseen collators and editors who have provided us with these shocks and thrills.

In any case, problem-setting and problem-solving remain. The filmmakers have pursued the implications of a narrow set of stylistic choices, and that pursuit comes with both rewards and risks. Meanwhile, other filmmakers may take up the challenge and try to surpass what this series has achieved: limited but genuine experimentation within mainstream conventions. Competing with each other and with their own achievements, filmmakers are pressed to discover new, if narrow, niches in Hollywood’s ecosystem.

E. H. Gombrich’s comment about artists’ tasks comes from his interview with Didier Eribon, Looking for Answers, p. 168. George Watson has some brief but helpful comments on fake memoirs and the discovered-manuscript convention in The Story of the Novel, pp. 15-22. Wikipedia includes a useful list of pseudo-documentaries and discovered-footage here, but calls them “found-footage films,” as most horror aficionados seem to do. As I indicate in the entry, that term confuses these fiction films with what has for a long time been a genre of experimental filmmaking. See for an overview William Wees’ 1993 book Recycled Images: The Art and Politics of Found Footage Films.

On Paranormal Activity, a helpful chronology is available at Dread Central. The chronological collection of the first three films available as a download includes a few extra scenes but omits some things as well, including some of the “official” titles marking the material as recovered footage. In an incisive analysis, Nicholas Rombes praises Paranormal Activity 2 as verging on avant-garde cinema.

Series creator Oren Peli has also directed The Chernobyl Diaries (2012), which has a pseudo-documentary quality at times. More peculiar and puzzling is the film Catfish (2010) by Henry Joost and Ariel Schulman. Many viewers and critics were unsure whether Catfish was a straight documentary or a reenacted one, perhaps with fictional elements added. Whatever the case, it made Joost and Schulman likely candidates for directing the last two installments of the Paranormal franchise. Schulman discusses the transition to studio filmmaking here, while also filling in some background on the Paranormal team’s working methods.

I regret that some of these illustrations are tiny, but I would have had to make them very large for full visibility, and then their quality would have suffered (and the entry would have been even longer). As should be evident, these films need to be seen on a big screen for all their details to be clear.

For a more disconcerting experiment in mechanized camera pickup in a fiction film, see Lars von Trier’s The Boss of It All (2006), discussed here.

Paranormal Activity 2 (2010): On the right, Ali peers in the window as Abby approaches, sniffing.