The ten best films of … 1922

Monday | December 31, 2012 open printable version

open printable version

Dr. Mabuse, der Spieler, Part 1.

Kristin here:

As the end of the year approaches and critics are posting their ten-best lists for the year, David and I once again fail to follow that tradition. Instead, we follow our own custom, now six years old, and turn our historians’ eyes back ninety years to offer ten great films from 1922. Of course, there are many films from the silent era that are lurking in archives, waiting to be discovered. Still, pointing to some noteworthy films we do have may help viewers to explore that rich period of cinema’s past.

Our previous lists can be found here, for 1917, 1918, 1919, 1920, and 1921.

For the past two years, I’ve noted that it was difficult to fill out the list of ten masterpieces. I keep thinking that I’ll get to a year where I won’t have to say that, but 1922 turns out not to be that year. Some titles were obvious, but the last one or two took some hunting.

As usual, one problem is that so many films are lost. Not one of John Ford’s three films of 1922 survives. In other cases great directors made lesser films. Important though Das Weib des Pharao was in Ernst Lubitsch’s career, partly because it shows him quickly picking up influences from Hollywood films, I can’t rank it among his first-rate titles. The same is true of Victor Sjöström, whose Vem dömer isn’t up to the level of other films like The Outlaw and His Wife.

Some of the films here, then, we consider classics but not masterpieces. Still, they have been influential and are well-regarded by other critics and historians. We’ll just call attention to them and let people form their own opinions.

Germany rules

But here are two full-fledged masterpieces, both from the German Expressionist movement. They demonstrate the potential for popular genres—here the horror and master-criminal genres—to achieve the highest level of filmmaking.

Few of F. W. Murnau’s early films survive, but there’s no doubt that he hit his stride in or before 1922. He made two outstanding films that year, Der brennende Acker (“The Burning Earth”) and Phantom, along with one of his very finest, Nosferatu. It is the earliest surviving film adaptation of Bram Stoker’s Dracula. (“Nosferatu” is Rumanian for “vampire.”)

Nosferatu is generally considered an Expressionist film, though there are only a few of the stylized sets that we tend to think of as vital to that artistic movement. Murnau instead mostly uses a combination of staging and framing in real locales to create echoes of shapes between characters and their surroundings, something usually accomplished through more painterly means in films like Das Cabinet des Dr. Caligari and Die Nibelungen. The nested arches in the left image frame Hutter’s arms, while Ellen’s forlorn slump on the bench as she awaits her husband’s return is juxtaposed with the leaning crosses that hint at fruitless vigils in the past.

One of my favorite moments in Nosferatu comes during the scene where Count Orlock is about to attack Hutter in one of the bedrooms in his castle. Ellen, at home in Wisburg, somehow senses this and in a panic throws out her arms in a desperate appeal for mercy. Orlock turns and looks away from Hutter, and the next shot again shows Ellen’s appeal.

It is a classic shot/reverse-shot situation, and yet the two are in different countries, many miles apart. The situation is ambiguous. Does Orlock sense Ellen’s appeal? Does he somehow magically see her from afar? Whichever is the case, he does leave Hutter’s room, and the clear implication is that her gesture has caused that withdrawal. Such a treatment of space is unusual, to say the least.

“False” eyeline matches or shot/reverse-shot passages linking distant characters were already fairly conventional. Hoping to put another of Maurice Tourneur’s films on our ten-best list, I watched his 1922 Lorna Doone. Though it has some marvelous passages, especially in the final battle, I couldn’t justify including it. Still, it provided a more conventional version of the false shot/reverse shot. In a scene where the hero thinks of Lorna, looking off front right, the following shot shows her thinking of him and looking off left.

They are in houses on neighboring estates, but they certainly cannot see each other. Moreover, there’s no indication that either suspects the other one is thinking of him/her. There is no ambiguity. Clearly the lovers are simply daydreaming about each other. The Nosferatu scene is more puzzling and evocative.

There is much more that once could say about Nosferatu—especially the experimentation with fast motion, negative footage, and pixillation to render the supernatural nature of the vampire—but I leave that for the reader to discover. There are a number of DVD versions available, but the Kino one contains the restored print and a documentary about the film’s production; the restoration is also available in the UK from Eureka!.

If this blog is still functioning in ten years, our list will definitely include a second great vampire film, Carl Dreyer’s Vampyr.

While Nosferatu plays on exotic, historic fantasy, Fritz Lang’s Dr. Mabuse, der Spieler (“Dr. Mabuse, the Gambler”) places its bizarre crime story squarely in contemporary Berlin. Mabuse (the incomparable Rudolf Klein-Rogge) is a master criminal with hypnotic powers, a man of innumerable disguises who lures his victims into gambling, whether in casinos or on the stock exchange. He also steals crucial documents to manipulate stock prices and controls the lives of many of the main characters. Throughout the lengthy plot, Detective von Wenk follows Mabuse’s trail, himself eventually falling under the criminal’s spell before exposing Mabuse’s identity.

Unlike with Murnau, we now have all of Lang’s early films and can judge his entire career. Arguably his first great film was Der müde Tod, which was on last year’s list. The first of his three Dr. Mabuse films (the others being Das Testament des Dr. Mabuse, 1933, and his last film, Die tausend Augen des Dr. Mabuse, 1960) was a step upward. It was made as a two-part serial: Der grosse Spieler—Ein Bild der Zeit (“The Great Gambler—A Picture of the Time”) and Inferno: Ein Spiel von Menschen unserer Zeit (“Inferno: A Play about People of Our Time”); together the parts run about four and a half hours.

The plot of Dr. Mabuse, der Spieler is very complicated and demonstrates Lang’s extraordinary ability to present a narrative visually. His sets, lighting, and staging are impeccable and already recognizably Langian. Consider the frame at the top of this entry.

In a gambling den, von Wenk, at the center top, and two important female characters, Countess Told, beside von Wenk, and Cara Carozza, left foreground, are staring at a rich old lady who has just gambled away a huge amount of money, caught by Mabuse’s spell. Her loss is the central action, yet she is placed so low in the frame as to be recognizable primarily by her silly beaded hat. Her gigolo, partly offscreen at the right, considers his position in the light of this disaster. Cara reacts with horror, the Countess and von Wenk with distress and sympathy. The other woman is an onlooker.

The tableau style of staging, keeping all the significant characters onscreen and moving them by slight increments to stress each character in turn, is still in play here, but the camera is closer to the actors, and they don’t move much. This isn’t just a tiny moment caught in the midst of a shifting composition. This is the composition. It looks remarkably modern. Each character, in his or her own way, is wondering, as we are, what has brought this minor character to such a pass. And she is tucked into a corner of the frame, as Lang will do in later films.

Dr. Mabuse‘s stress on “Our Time,” contemporary Weimar Germany, brings in the film’s Expressionistic elements. Expressionism here isn’t an all-encompassing filmic treatment that reflects a fantasy world or the psychological extremes of the characters. Instead, it is a tangible decorative impulse pervading the modern city. Below, von Wenk responds with distaste upon first viewing Count Told’s collection of modern art; yet in another scene, he calmly dines with an associate in a thoroughly Expressionist restaurant:

The bits of set visible in the background of this entry’s top frame indicate that the casino is another Expressionist locale.

The restored two-part film is available from Kino in the USA and in “The Complete Fritz Lang Dr. Mabuse Box Set” and from Eureka!’s “Masters of Cinema” series in the UK.

The grandiose and the modest as French Impressionism defines itself

The French Impressionist film movement can be said to have begun in 1918 with Abel Gance’s La Dixième Symphonie, though it has relatively few moments of the sort that came to define the style. It primarily uses superimpositions and split screen to convey a sense of the composer’s musical performances. Films by critic and theorist Louis Delluc followed, and Marcel L’Herbier explored pictorial and poetic effects in his early films. Highly subjective uses of film technique, which we think of as crucial to Impressionism, appeared in a really consistent way in El Dorado (1921), which was the first film of the movement to appear on our ten-best lists.

In 1922, the movement gained momentum with Gance’s monumental La roue. Many critics and historians consider this and Gance’s Napoléon masterpieces. I consider them more uneven, with brilliant stretches mixed in with melodramatic, sentimental, even occasionally maudlin scenes mixed in. Few people have seen all the surviving footage from La roue. The shorter versions available tend to eliminate the sentimental bits, which often run on and on. I’ve already voiced my opinions, favorable and less so, in the entry “An old-fashioned, sentimental avant-garde film,” posted when the longest version available on DVD was released by Flicker Alley.

I mentioned there that the footage cut from the shorter versions of the film seemed to be some of the sentimental moments. One such scene seems to me unintentionally risible. The hero, Sisif, is a veteran train engineer; he has suffered an injury that is slowly causing him to go blind. Unable to face turning his beloved engine over to a rival engineer, he ponders destroying it. Sitting on the engine, he asks whether it would not prefer being wrecked to being turned over to another driver. The replies to his questions are given as titles superimposed over the train:

This is, I think, representing Sisif’s delusion that the engine speaks to him, but I’m afraid it comes across as if the train is suddenly talking out loud. In a sound film it’s easy to understand that a sound can originate subjectively in the mind of a character. People don’t, however, tend to imagine sounds as written words!

There’s no question that La roue has some extraordinary scenes. The opening train wreck and its aftermath are justly famous, as is the accelerating editing in the scene in which Sisif drives his stepdaughter Norma, with whom he is secretly in love, into the city to marry another man; his agitation and thoughts of crashing the train are reflected by the increasingly shorter shots. And although it’s dangerous to make claims about any film having the first use of a given technique (usually someone will find an earlier one), Gance seems to have been the first to use stretches of single-frame editing. These occur at a moment when one character in a crisis situation (trying to avoid spoilers here) recalls a cluster of scenes from his past. Maybe the Soviet Montage directors would have come up with that idea on their own—but maybe not. Along with El Dorado, La roue helped define what were to be the main traits of Impressionism.

One thing I didn’t mention in my entry on La roue is the striking contrast between the romance plot and the many scenes shot around the train-yard, which were shot on location. They add a gritty realism that does much to make up for the melodrama—a realism that largely disappears in the final portion, when Sisif is transferred to a mountain location to run a funicular train.

Most of the French Impressionist directors, and particularly Gance, L’Herbier, and Delluc, were concerned to prove that cinema was an art form. Their films tended to be serious, poetic, and based more on in-depth psychological portraits than on the more action-oriented films of Hollywood. They were also clearly made by Artists with a capital A. Gance and L’Herbier liked to start their films with close-ups of themselves staring into the lens with artistic fervor. L’Herbier’s photos included autographs. The films were designed to appeal to an intellectual crowd, though Gance’s were also highly successful at the box-office. Other directors’ films weren’t hits, however, and as the decade progressed more of them played only in the ciné-clubs and art theaters that sprang up.

Another Impressionist film of 1922, Jacques Feyder’s Crainquebille, took a very different tack. I remember seeing Crainquebille decades ago and not thinking much of it, though it has long been considered a classic. Now, however, watching the 2005 restoration by Lenny Borger and Lobster Films, I think it’s much more interesting. That’s not surprising, given that the print I originally saw was probably the 50-minute American release version, and the restoration adds half again as much footage, bringing it to 76 minutes. (The Internet Movie Data Base lists the original Belgian release print as 90 minutes, so presumably what we have is still not complete.)

Crainquebille has been admired for its realism and for the performance of a well-known stage actor of the day, Maurice de Féraudy in the title role. Jérôme Crainquebille is an elderly vegetable peddler, and much of the film was shot in the streets and markets of Paris, sometimes using long lenses to capture scenes of crowds and passers-by, unaware of the camera’s presence. But what struck me upon seeing it again is that Feyder was trying to make an Impressionist film for ordinary cinema-goers, perhaps the working-class people who could relate best to Crainquebille’s situation and milieu.

True, the film has a prestigious pedigree, being an adaptation of an Anatole France novel and starring a famous theater actor. Yet the story is simple and told in a relatively straightforward manner. Most of the action arises from a misunderstanding: A gendarme, thinking Crainquebille has insulted him, arrests him. A leisurely scene shows the protagonist enjoying the unusual luxury of his prison cell: a comfy bed, free meals, a toasty radiator, hot and cold water in a pristine sink, and a floor clean enough to eat off. A working-class audience would probably find this wryly amusing.

More telling, though, is the fact that when the typical camera techniques of Impressionism are used, Feyder inserts explanatory intertitles just before the subjective shots occur. This particularly happens in the long central trial scene. When the gendarme steps up to testify, a title informs us, “In Crainquebille’s eyes the Constable looked as important as his testimony.” We see Crainquebille gazing forlornly off right front and then his point-of-view of the witness, looming like a giant over the courtroom:

Subsequently a passerby from the scene of the “crime,” Dr. Mathieu, testifies on Crainquebille’s behalf. A title informs us, “To Crainquebille this testimony seemed to carry little weight.” We see a similar pair of shots, with the witness a tiny figure in the midst of the court. Naturally Crainquebille is found guilty and goes off to two further weeks of free room and board.

The next scene begins with an intertitle, “Dr. Mathieu’s Nightmare.” We see Mathieu in bed and then are taken into his nightmare, which depicts the court as a stylized, hellish place with the judges fearsome figures who leap onto their desk in extreme slow motion. (I have no way of knowing what the source of these intertitles is, so I must simply assume here that they reflect what was in the original film.)

Such heavily signaled experiments wouldn’t in themselves make Crainquebille a real masterpiece, but at a time when Impressionism was just gelling as a recognizable style, it seems a laudable attempt to find a non-elitist way to use it. In addition, the shots of the market where Crainquebille goes each morning are quite lovely, taken from neighboring rooftops with telephoto lenses.

As to what was restored in this version, there is remarkably little information on the internet. My notes from an archive viewing of the shorter version in 1984 suggests that the entire opening sequence in the restored version is “new.” It consists of Crainquebille and other vegetable peddlers pushing their carts across Paris to the main market. They pass through a wealthy district, which is characterized with vignettes of rich people’s decadence. The peddlers then pass through a high-crime district, with police rounding up criminals and prostitutes. (The inclusion of prostitutes suggests why this scene was cut for the American version.) The shorter version begins with the market scene and leads quickly to a scene in which Crainquebille rescues a poor newsboy from bullies, and the the scene where he is arrested follows. The entire character of Dr. Mathieu, the sympathetic witness, was cut, so the short version has a briefer trial scene and no nightmare. The action that follows Crainquebille’s release from prison is the same as in the restored version.

Crainquebille is available as part of a set, “Rediscover Jacques Feyder French Film Master,” along with restored versions of two of his other major films of the period, L’Atlantide (as “Queen of Atlantis,” 1921) and Visages d’enfants (as “Faces of Children,” 1925).

Hollywood dramas: The somewhat old and the somewhat new

The two Hollywood films on this year’s list are very familiar Hollywood classics, so I won’t spend much time introducing them.

D. W. Griffith probably appears for the last time in our 90-year-ago lists with his historical epic, Orphans of the Storm. This tale of the French Revolution featured the last appearances for Griffith of Lillian and Dorothy Gish, whose first film roles had been in his American Biograph short, An Unseen Enemy, in 1912. They play apparent sisters, Henriette and Louise (though Louise is in fact adopted) living in a Normandy village. Louise becomes blind, but Henriette takes her to Paris in the hope of finding someone who can restore her sight. Upon arriving, they are separated and victimized, Henriette by the decadent nobility, Louise by the dishonest poor. Eventually they are caught up in the Revolution, and Henriette is nearly executed at the guillotine.

As in his best features, Griffith combines an ability to represent melodramatic stories of idealized, virginal heroines alongside naturalistic, convincing images of the poor:

Orphans of the Storm represents the lingering influence of the Victorian theater on Griffith. The slightly later Naturalistic strains of nineteenth-century literature are evident in the cynical narratives of Erich von Stroheim. His first film, and the most completely preserved, was Blind Husbands, featured in our 1919 ten-best list. As I said there, Blind Husbands is my favorite von Stroheim film, with its relative light take on attempted seduction, near marital infidelity, and retribution. Foolish Wives took the theme much further, with the director again playing the heartless rake, Count Wladislaw Sergius Karamzin. Rather than pursuing one vulnerable wife, he seduces every woman in sight, including a hotel maid and an invalid, bedridden girl (above whose bed a crucifix hangs, to make sure we grasp the sinfulness of Karamzin’s lust).

Von Stroheim famously reconstructed the casino and surrounding buildings of Monte Carlo, resulting in a budget overrun. Universal made the best of his profligacy by advertising Foolish Wives as the first million-dollar movie ever. (Whether it really was or not we shall probably never know.)

Although much of the film is fairly conventional, with shot/reverse-shot conversations, von Stroheim experimented occasionally. At the left below, he shoots into a small mirror as Karamzin secretly ogles the heroine, who is behind him, as she undresses. In a number of shots von Stroheim films through a scrim to give a canvas-like effect to a composition. Here the invalid girl whom the villain eventually tries to rape is seen with her doting father.

As with all of von Stroheim’s films after Blind Husbands, Foolish Wives was taken out of his hands by the studio and shortened considerably. Much of this was done by trimming the lengths of individual shots. The original film apparently does not survive, so it is impossible to assess the director’s style thoroughly, especially when it comes to editing. The revisions were not nearly as great, however, as with his 1924 film Greed, which was cut by well over half. Thus of all von Stroheim’s 1920s films, Foolish Wives is probably closer to what he intended than most. The standard version of the film (restored by the American Film Institute but not of sterling visual quality) is available from Kino in an edition that includes a 78-minute documentary, The Man You Loved to Hate, written by von Stroheim expert Richard Koszarski.

Hollywood silent comedy

Every year our list visits the great three slapstick comedians: Chaplin, Keaton, Lloyd. Sometimes it’s all three, sometimes two. They have all been working their way through shorts to the great features of the 1920s. Chaplin made it there last year with The Kid. In 1922 he had a light year, reverting to two-reelers with The Idle Class and Pay Day, so we’ll skip him here and pick him up again later.

In 1922 it was Harold Lloyd who moved up to features with Grandma’s Boy. Not on a level with some of his later films, like Girl Shy (sure to be high on our 2014/1924 list), but a real charmer with some classic Lloyd routines.

Lloyd is undoubtedly best known for his “thrill” comedies like Safety Last (1923 and heavily favored to feature on this list next year), where he climbs a skyscraper. Still, his more typical roles in the features show him beginning as a timid or socially inept young man who gains courage or skill in the course of the narrative. In Grandma’s Boy, an amusing and touching scene introduces the hero as a perpetually frightened child, unable to stand up even to littler boys who steal his lunch. Once he has grown up, his diminutive grandmother manages to chase off an intruding hobo with her broom after the Boy (none of the characters is named) has failed do so:

Despite his timidity, the Boy has managed to attract a Girl, and a Lloydian string of gags occurs when she invites him and his thuggish Rival to visit her at home. Grandma polishes the Boy’s shoes with goose grease and dresses him in an antiquated suit with mothballs in the pockets. Once at the Girl’s house, the Boy attracts the unwanted attentions of a litter of kittens determined to lick his shoes. When the Girl reacts badly to the mothball-scented suit, the Boy hides the balls in a box of candy. This leads to a hilarious scene in which he and the Rival both accept some “candy” from the Girl and end up grimacing in sync and trying to smile every time the Girl glances at them.

As with many good classical films, almost exactly halfway comes a turning point: the sinister hobo has robbed a jewelry store and shot a man. The film’s second half becomes an extended chase in which the reluctant Boy is enlisted as a deputy. Thanks to a little psychological trick played by the Grandmother, he wins out.

Grandma’s Boy is available in the indispensable “The Harold Lloyd Collection,” one of New Line Home Entertainment’s finest achievements, or separately with some other features as Volume 2 of the same set, or even more separately with seven shorts from Kino.

Buster Keaton was still making shorts in 1922, but this doesn’t put him at a disadvantage in our list. Experts agree that of Keaton’s twenty starring shorts (after his work as sidekick to Fatty Arbuckle), the best are The Boat (1921) and Cops (1922). Both are strongly touched by the streak of surrealism that frequently shows up in Keaton’s work—as in the dream-within-a-film scene that forms the bulk of Sherlock Junior (1924).

In Cops, Keaton plays a young man trying to impress his beloved by making good in some fashion. He is duped by a crook pretending to be evicted, who sells him the furniture of a family moving house, along with the horse and wagon that has come to transport it. Taking off through the city with the furniture he intends to resell at a profit, Keaton finds himself in the midst of a police parade and innocently accused of throwing a bomb actually lobbed by an anarchist. Chaos breaks loose. No matter where our hero runs, everyone he encounters turns out to be a cop—including his sweetheart’s father and the owner of the furniture.

The film is full of wonderful sight gags. Keaton hangs his hat on the protruding hip bone of a scrawny horse, and he tries to make a mustache disguise out of a clip-on tie.

Cops is available in Kino’s collection of Keaton shorts and in its collection of most of the features and shorts. Also available in the UK in the Eureka! “Masters of Cinema” box set of all Keaton’s shorts.

Next year, Our Hospitality!

Documentary and storytelling

Although we’re not overwhelmed with admiration for our final two films, they demanded inclusion because they are recognized as canonical classics.

Nanook of the North has frequently been described as the first feature-length documentary. Here’s an example where it was dangerous to call something first. There is in fact at least one earlier, filmed at the opposite end of the Earth: Frank Hurley’s South (1919), a record of Ernest Shackleton’s famous shipwrecked expedition to the Antarctic. But Nanook found a much wider public and became a classic, while South disappeared until 1998, when it was restored by the British Film Institute.

Nanook also had the advantage of a charismatic central figure and his attractive family, a picturesque depiction of Inuit life, and a carefully scripted story that included moments of danger during a walrus hunt and humor during a visit to a trading post.

Still, the film has drawn criticism for its extensive manipulation of reality. “Nanook” was in fact an Inuk named Allakariallak, and the woman represented as his wife was not married to him. Scenes were staged, as when an already-dead seal was used in a hunt. Nanook expresses amazement at a phonograph, though he was already familiar with such devices. The Inuit had already adopted firearms for hunting by the time Flaherty filmed them, but he requested that they use spears instead.

As has been pointed out, however, Flaherty was trying to present a slightly earlier phase of the Inuit culture, preserving a lifestyle that was rapidly changing. Moreover, the documentary mode had previously consisted largely of actualities and travelogues, and there was little precedent for what Flaherty was doing. For decades after Nanook (originally subtitled A Story of Life and Love in the Actual Arctic), documentaries tended to be structured fairly explicitly as tales with entertainment value. In the wake of cinéma vérité, the issue of filmmakers interfering with their subjects and staging scenes has become controversial, but it was not a great concern in the 1920s.

If we accept the notion that this is a documentary with considerable manipulation, we can credit the film with conveying a good deal of information about the Inuit of a slightly earlier period. The igloo-building scene is interesting and informative, even if we know that the interior shots had to be made in an igloo actually open on one side to provide light for the camera.

Nanook of the North was restored and released by the Criterion Collection in 1999.

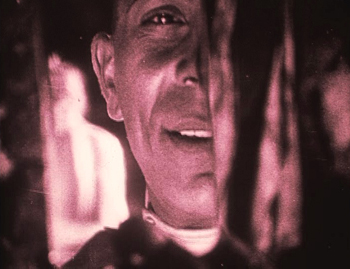

Although it also appeared in 1922, Benjamin Christensen’s Häxan tends not to get equal credit as the supposed first feature-length documentary. Perhaps that is because it barely qualifies as a documentary. It’s not clear what other genre or mode it belongs to, though it tends to be admired mostly by fans of horror films.

Häxan purports to be a lecture on the history of witchcraft. Its English title is Witchcraft through the Ages, though the original title means simply “Witches.” The first reel consists of a series of images from books both scholarly and sensational, showing ancient images of supposed witches or witch-like creatures. The claim is that witchcraft has been a universal concept in cultures throughout history. Whether this is true I can’t say, but the images shown of ancient Egyptian deities are not witches but protective figures.

In the second reel, Christensen begins to illustrate the points being made with staged scenes of witches, surrounded by animal skeletons and other macabre items, many of them used in potions. Gradually the staged scenes develop into a narrative set in the Medieval or early Renaissance era, with one old woman being accused of witchcraft and tortured. She finally admits to being a witch and names her accusers as witches, and the imprisonment and torture spread. Like Dreyer in Leaves from Satan’s Book and Day of Wrath, Christensen condemns the very notion of witch-hunting and the hypocrisy and cruelty of the Church. Yet he shows a considerable fascination with torture methods—although in place of graphic scenes he presents static shots of contorted limbs and exhausted victims.

The true strangeness of the film, however, comes from its visualization of demons and devils as real beings. They conducting orgies, fly on broomsticks, and attempt to seduce people into evil and madness. Perhaps we are to take these images as what the Church assumes is happening, but there is no indication of that. One has to suspect that ultimately the educational “lecture” premise of the film, which is handled in a perfunctory way, is an excuse for staging scenes that range from quite powerful (see below) to merely cartoon-like, with people dressed up in crudely made costumes.

At the end the lecture mode returns, with an unconvincing series of comparisons of witchcraft with modern-day activities.

Whatever one thinks of the subject matter and its treatment, the film’s cinematography is extraordinarily beautiful.

Häxan has been restored by the Svenska Filminstitutet and was released on DVD with optional English subtitles. The restoration is available in the USA from the Criterion Collection, but I haven’t seen it or its extras. The Criterion package includes a version of the film narrated by William S. Burroughs. I haven’t seen it, but according to David’s memory of the croaky, world-weary voice-over, it adds another layer of weirdness to the proceedings.

For many years Häxan, as the only film by Christensen that was available for viewing outside archives, gave a rather distorted view of this director. Then his two earlier films, Det hemmelighedsfulde X (“The Mysterious X,” 1914) and Hævnens Nat (“Night of Revenge,” 1916) became more widely available. They were revelations—beautifully shot, tightly scripted, exciting movies. Those who don’t like Häxan should definitely watch these; they are quite different. Both are available on a single DVD from the Danske Filminstitut. The DVD has English intertitles, and the online shop is bilingual, Danish and English.

Häxan