Archive for 2012

COGNITIVISTS STORM BIG APPLE! BIG APPLE ASKS, “WHAT’S A COGNITIVIST?”

The final SCSMI 2012 banquet, held on the tenth floor of the NYU Kimmel Center for University Life, Rosenthal Pavilion.

DB here:

Most years I offer an entry recording some events at the annual meeting of the Society for Cognitive Studies of the Moving Image. We did hold our conference–and a swell one it was, starting Wednesday at Sarah Lawrence College and wrapping up at the Cinema Studies department of New York University last Saturday. I heard many excellent papers and panel discussions. (The schedule is on a pdf here.) The event was also graced by keynote lectures by Alva Noë and Noël Carroll, and a night of splendid, eye-warping films by Ken Jacobs, no stranger to this blog (here and here and here). Malcolm Turvey of Sarah Lawrence and Richard Allen of NYU did an excellent job of coordinating the SCSMI event.

But I can’t offer my usual conference roundup this time. Kristin and I just got back last night, and we have only three days in Madison before taking off for Il Cinema Ritrovato. In those three days we have a hell of a lot to do, including setting me up for Medicare (!), as I’ll turn 65 during our trip. But I did want to supplement a small runup piece to the conference a couple of weeks back.

A few days after that post, I received the most recent issue of Projections, a journal with which SCSMI is affiliated. It’s stuffed with worthwhile pieces: Gerald Sim’s overview of the digital revolution (if any) in cinematography; Barbara Flueckiger’s essay, “Aesthetics of Stereoscopic Cinema”; Mark J. P. Wolf’s study of imaginary worlds on film; and James E. Cutting, Kailin L. Brunick, and Jordan DeLong’s correction of one claim they made about shot lengths and film acts. (Kristin discusses their project in this entry from last year.)

A few days after that post, I received the most recent issue of Projections, a journal with which SCSMI is affiliated. It’s stuffed with worthwhile pieces: Gerald Sim’s overview of the digital revolution (if any) in cinematography; Barbara Flueckiger’s essay, “Aesthetics of Stereoscopic Cinema”; Mark J. P. Wolf’s study of imaginary worlds on film; and James E. Cutting, Kailin L. Brunick, and Jordan DeLong’s correction of one claim they made about shot lengths and film acts. (Kristin discusses their project in this entry from last year.)

As if all this weren’t enough, the issue includes a lively and probing roundtable on Continuity Editing, with a superb synoptic article by Tim Smith summing up his eye-tracking research. (His study of There Will Be Blood is our now-classic guest blog.) Tim’s article is an ideal introduction to his wide-ranging research program. Several other scholars comment on Tim’s “attentional theory of continuity editing”: Paul Messaris, Cynthia Freeland, Sheena Rogers, Malcolm Turvey, Greg Smith, and Daniel T. Levin and Alicia M. Hymel. Tim replies to their criticisms in a follow-up piece. This sort of dialogue occurs very rarely in film studies, and it’s to be applauded. I think such serious and courteous exchanges are the mark of a mature, or at least maturing, discipline.

You can learn more about Projections here and read a sample issue here. If your library doesn’t subscribe, maybe you can hint that it should. Although it’s hard to determine the image format of the swirling filmstrip on the cover (image ratio and perfs are puzzling), note that at least it is film.

I learned so much from this year’s get-together that you shouldn’t be surprised if pieces of it float into upcoming blog entries. And in 2013, there’s always Berlin.

From Sam Wass, Parag Mital, and Tim Smith’s paper, “Cutting through the blooming, buzzing confusion: Signal-to-noise ratios and comprehensibility in infant-directed screen media.”

I Love a Mystery: Extra-credit reading

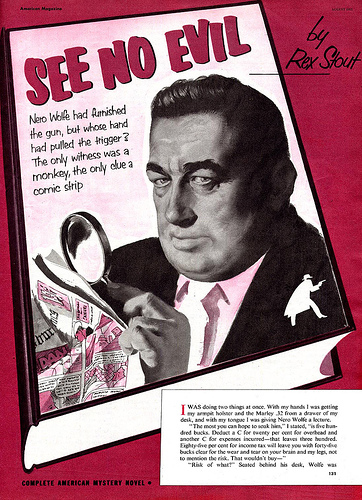

Thornton Utz illustration for Rex Stout novella from American Magazine, 1951. Obtained from the excellent site Today’s Inspiration.

DB here:

Over the next few months, I’ll be traveling with a talk on Hollywood cinema of the 1940s. The ideas I’ll propose are destined for a book about narrative norms during that period. Mystery fiction is important to that lecture, but I don’t have room there to supply much background about the relevant conventions. So I’m sketching in this background here, for people who might hear the talk somewhere or who might just be curious. Consider this as another experiment on the blog, using the web to supplement a lecture.

Although the lecture is mostly about cinema, this entry is mostly about novels and plays. But I’ll mention film here and there, and you’ll notice that some of the books and plays I mention were adapted for the screen.

A mega-genre

The first half of the twentieth century saw an explosive expansion in genres built around mystery and suspense. The most obvious genre is the detective story. In the wake of Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes tales, a great many writers developed and elaborated on the idea of the master sleuth, the genius of observation and reason. Central to this tradition was the puzzle that could be solved by careful noting of clues and meticulous reasoning about them, supplemented by a good knowledge of human nature or local customs. The author needs to keep us in the dark about both the crime and the detective’s chain of reasoning; hence point-of-view figures like Watson, who can be appropriately confounded, relay the detective’s cryptic hints, and marvel at the final revelations.

Readers quickly learned the conventions, so writers had to innovate constantly. Sometimes a writer was original on more than one front. For example, R. Austin Freeman created a revamped Holmes surrogate in a scientific criminologist, Dr. Thorndyke, while also creating a new narrative structure: that of the “inverted” tale. The first section of the story follows the criminal who commits the crime; the second part details how Thorndyke, using evidence and inference, solves it.

Historians of the detective story have a standard account that goes like this. The puzzle-centered plot developed to its apogee in the 1920s and 1930s, chiefly in Britain, and was picked up in the United States. In books like The Murder of Roger Ackroyd (Agatha Christie, 1926), The Canary Murder Case (S. S. Van Dine, 1927), The Unpleasantness at the Bellona Club (Dorothy L. Sayers, 1928), The Poisoned Chocolates Case (Anthony Berkeley, 1929), The Egyptian Cross Mystery (Ellery Queen, 1932), and The Crooked Hinge (John Dickson Carr, 1938), the crimes are deeply puzzling, even fantastical, and the solutions ever more recherché.

Historians of the detective story have a standard account that goes like this. The puzzle-centered plot developed to its apogee in the 1920s and 1930s, chiefly in Britain, and was picked up in the United States. In books like The Murder of Roger Ackroyd (Agatha Christie, 1926), The Canary Murder Case (S. S. Van Dine, 1927), The Unpleasantness at the Bellona Club (Dorothy L. Sayers, 1928), The Poisoned Chocolates Case (Anthony Berkeley, 1929), The Egyptian Cross Mystery (Ellery Queen, 1932), and The Crooked Hinge (John Dickson Carr, 1938), the crimes are deeply puzzling, even fantastical, and the solutions ever more recherché.

It’s hard for us to conceive today how massively popular these puzzle books were. Van Dine’s first novels were bestsellers comparable to Jonathan Kellerman’s books today. Just as important, the detective story was granted quasi-literary status. Magazines and newspapers that wouldn’t dream of reviewing romance or adventure fiction devoted space to detective stories, sometimes even setting up separate columns or sections for reviews. It was believed, rightly or wrongly, that whodunits had a more intellectual readership than Westerns or science fiction.

At about the same time, according to the standard account, a counter-current was swelling. In the pulp magazines of the 1920s, the “hard-boiled” detective emerged as an alternative to the master sleuth. The prototype is Dashiell Hammett’s Continental Op in stories through the late 1920s, to be followed by Sam Spade in The Maltese Falcon (1930). Strikingly, Hammett and other hard-boiled writers don’t wholly abandon the basic idea of solving a mystery through some sort of reasoning. The differences have to do with realism. The crimes, however, aren’t usually fantastical ones like the Locked-Room problem; the killings tend to be mundane. If the white-glove detective’s only real opponent is a master criminal like Professor Moriarty, the hard-boiled detective faces off against organized crime, or at least people who commit murder outside upper-crust parlors and remote country houses. Clues are less likely to be physical, and more psychological, depending on bits of behavior or flashes of temperament. Raymond Chandler and others took the hard-boiled initiative into the 1940s, and the brute detective, who solves crimes with boldness, insolence, and a pair of fists, occasionally supplemented by torture, found bestseller status in Mickey Spillane’s I, the Jury (1947) and subsequent novels.

I’d argue that some writers could blend the master-mind detective and the tough guy. Erle Stanley Gardner’s Perry Mason was one such hybrid, though leaning closer to the hard-boiled model. Rex Stout solved the problem neatly by creating two detectives: the insolent legman Archie Goodwin serves as a hard-boiled Watson to sedentary Nero Wolfe. But on the whole, historians tend to assume that the Holmesian superman and the puzzle-dominated plot were swept aside by the rise of the tough-guy detective solving mysteries that were grittier and more “realistic” than what had preoccupied Golden Age writers.

Two other major developments are typically highlighted by historians. There was the police procedural, perhaps initiated by Lawrence Treat’s V as in Victim (1945), and explored with great ingenuity in the novels of Ed McBain. There was also what Julian Symons has called the “crime novel,” the story of psychological suspense, with Patricia Highsmith’s Strangers on a Train (1950) serving as a good example. Both of these genres have proven popular to this day (CSI as a procedural, the films of De Palma as psychological thrillers).

A tree and its branches

Like most histories hovering fairly far above the ground, the standard account traces some main contours of the landscape but misses some interesting byways. By taking Doyle as the prototype, this account tends to identify mystery fiction with detective plots in the Holmes mold. But mysteries come up in other forms.

The standard account has trouble accommodating the development of the spy genre, which often involves solving a crime, but less through abstract reasoning than by putting the hero through hairbreadth adventures. Think for instance of The 39 Steps, both the 1915 novel and the 1935 film.

More seriously, by identifying solving mysteries with the activities of professional, overwhelmingly male, detectives historians have neglected the powerful and popular tradition of the revived Gothic or “sensation” novel of the mid-nineteenth century. This is typified by Wilkie Collins’ Woman in White (1859-1860) as much as by The Moonstone (1868), often considered the first detective novel (largely because a detective figures as one of the characters, even though he doesn’t solve the mystery). Collins’ novels, along with those of Mary E. Braddock, updated the Gothic format through more complex plotting and multiple points of view. In the next century, Mary Roberts Rinehart, with The Circular Staircase (1908), has to be considered as important as Freeman. Rinehart’s plot introduces the crucial conventions of the mysterious house, the curious and brave woman who explores it, and the threats lurking behind placid domesticity. While the classic white-glove sleuth isn’t usually in much danger, The Circular Staircase and other updated sensation novels make the investigating figure a woman in peril. The sensation novel replaces cool rationality with fear and desperation.

More seriously, by identifying solving mysteries with the activities of professional, overwhelmingly male, detectives historians have neglected the powerful and popular tradition of the revived Gothic or “sensation” novel of the mid-nineteenth century. This is typified by Wilkie Collins’ Woman in White (1859-1860) as much as by The Moonstone (1868), often considered the first detective novel (largely because a detective figures as one of the characters, even though he doesn’t solve the mystery). Collins’ novels, along with those of Mary E. Braddock, updated the Gothic format through more complex plotting and multiple points of view. In the next century, Mary Roberts Rinehart, with The Circular Staircase (1908), has to be considered as important as Freeman. Rinehart’s plot introduces the crucial conventions of the mysterious house, the curious and brave woman who explores it, and the threats lurking behind placid domesticity. While the classic white-glove sleuth isn’t usually in much danger, The Circular Staircase and other updated sensation novels make the investigating figure a woman in peril. The sensation novel replaces cool rationality with fear and desperation.

Jane Eyre is an obvious source for Rinehart and her successors, and perhaps the association with women’s writing in general made historians and practitioners of the Golden Age mock the revived Gothic as too feminine, too far removed from the bluff masculine camaraderie of 221 B Baker Street. The Gothicists had their revenge: Daphne Du Maurier’s Rebecca (1938) outsold every other mystery novel of its time and sustained a cycle of new sensation novels by Mabel Seeley (The Chuckling Fingers, 1941), Charlotte Armstrong (The Chocolate Cobweb, 1948), and Hilda Lawrence (The Pavilion, 1946). The genre is maintained today by Mary Higgins Clark, Nicci French, and many other writers.

So mystery and detection formed a broader tradition than literary historians sometimes acknowledge. Another marginal form was the suspense thriller. Again, we can point to a woman: Marie Belloc Lowndes, author of The Lodger (1913). An early instance of the serial-killer plot, it’s also a tour de force of point-of-view; unlike the film versions, it restricts itself quite rigorously to what certain secondary characters know. Choices about narration and viewpoint are no less crucial to the thriller than to the Great Detective tradition.

The psychological thriller was revived during the Golden Age, sometimes by practitioners of the puzzle-story. Anthony Berkeley Cox, writing as Anthony Berkeley, noted in The Second Shot (1930):

The psychological thriller was revived during the Golden Age, sometimes by practitioners of the puzzle-story. Anthony Berkeley Cox, writing as Anthony Berkeley, noted in The Second Shot (1930):

I personally am convinced that the days of the old crime puzzle pure and simple, relying entirely upon plot, and without any added attractions of character, style, or even humour, are, if not numbered, at any rate in the hands of the auditors. . . The puzzle element will no doubt remain, but it will become a puzzle of character rather than apuzzle of time, place, motive, and opportunity. The question will be not “Who killed the old man in the bathroom?” but “What on earth induced X, of all people, to kill the old man in the bathroom?”

Cox went on to test his premises in Malice Aforethought (1931) and Before the Fact (1932). Both trace the schemes of wife-killers, but the first novel is told from the husband’s standpoint and the second from the wife’s. The latter book opens:

Some women give birth to murderers, some go to bed with them, and some marry them. Lina Aysgarth had lived with her husband for nearly eight years before she realized that she was married to a murderer.

There followed other domestic-crime psychological novels, notably Richard Hull’s The Murder of My Aunt (1934).

Sometimes suspense thrillers have a solid mystery at their center; this is common when the protagonist is a potential victim. Other thriller plots in effect present the first half of a Freeman “inverted” story, concentrating on the criminal’s execution of a crime and the resulting efforts to escape punishment. Both possibilities were on display in British stage plays of the 1920s and 1930s. In a sense Cox was beaten to the punch by Rope (1929), Blackmail (1929), and Payment Deferred (1931). Later examples are Night Must Fall (1935) and the woman-in-peril dramas Kind Lady (1935) and Gaslight (1938). Many of these plays were made into films.

The novel of suspense really came into its own in the 1940s, when it started to incorporate abnormal psychology. Patrick Hamilton, author of Rope and Gaslight, provided an influential novel as well, Hangover Square (1941). Cornell Woolrich and David Goodis, who mined this nightmarish vein, achieved posthumous cult status because, again, of the spell of film noir. Other suspenseful students of mania were Dorothy B. Hughes (In a Lonely Place, 1947), Charlotte Armstrong (The Unsuspected, 1945; Mischief, 1951, filmed as Don’t Bother to Knock), and Elizabeth Sanxay Holding (The Blank Wall, 1947, source of The Reckless Moment). Chandler called Sanxay Holding “the top suspense writer of them all.” We shouldn’t ignore the influence of Simenon’s romans durs, which were being translated and respectfully reviewed throughout the war years.

Yet another new wrinkle on the mystery thriller was the genre of courtroom novels. The Bellamy Trial (1927), which begins when the trial does and restricts itself almost completely to what transpires in the courtroom, popularized the pattern. Stage plays of the 1920s adopted the pattern too. The format proved irresistible for early talkies, as in adaptations of The Bellamy Trial (1929) and Thru Different Eyes (1929) and the radio-inspired Trial of Vivienne Ware (1932). Cox, who seemed to try his hand at every current trend, gave his own twist to the juridical mystery in Trial and Error (1937).

Most of these novels focused on the trial proceedings from the perspective of the defendant, but a few concentrated on those sitting in judgment. The Jury (1935), by Gerald William Bullett, characterizes the jurors singly before they gather and then shows the trial from their standpoints before taking us into the jury room to hear the arguments. Bullett’s novel finds an equally engrossing complement in Raymond Postgate’s Verdict of Twelve (1940). There were also Eden Philpotts’ The Jury (1927) and George Goodchild and C. E. Bechhofer Roberts’ The Jury Disagree (1934). We can immediately recognize the teleplay and film Twelve Angry Men as an updating of this minor line.

Merging and markets

The family tree of mystery, then, grew many branches in the 1920s and 1930s—the pure puzzle, the hard-boiled investigation, the spy story, the revised Gothic or sensation novel, and the suspense thriller, often of a psychological cast. Unsurprisingly, the genres began to mingle. Cox was perhaps the writer most interested in hybrids, but John Dickson Carr tried his hand at the thriller as well (The Burning Court, 1937), as did Agatha Christie in And Then There Were None (aka Ten Little Indians, 1940).

The process sped up during the 1940s, when writers began blending crime-solving with psychological suspense. We can get a sense of how the protagonist-in-peril side of the thriller melded smoothly with the enigma-based investigation by looking at the jacket copy of a fairly ordinary entry, Alarum and Excursion (1944):

Bit by bit, a gesture here, a sound there, Nick Matheny pieced together the awesome puzzle of the accident that had sent him to a sanitarium with traumatic amnesia. One by one he reconstructs, he probes the cirumstances of the explosion in his factory, the disappearance of his weak but beloved son, his wife’s strange attitude toward the new management of the business, and the status of the new synthetic fuel formula, which was so urgently needed.

As the dreadful picture unfolds itself, Nick escapes from the sanitarium to ferret out the sinister changes that have disrupted his business and brought his active life to an abrupt close.

Virginia Perdue, author of He Fell Down Dead, skillfully handles the difficult flash backs in this unusual psychological drama. There are many scenes where the tricks of thought, the tenseness of apprehension, the visions through the deserted streets of blacked-out memory poignantly work their stealth upon the mind of the reader.

Alarum and Excursion wasn’t adapted into a film, but reading this spoiler-filled jacket copy you can easily imagine the movie.

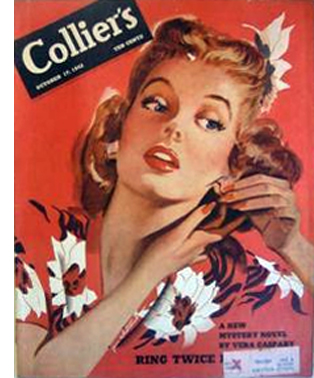

One more factor needs to be mentioned: the publication venues. Everybody knows that the hard-boiled tradition has its roots in Black Mask and other pulp magazines of the 1920s. What’s less often emphasized is the “slick-paper” market of the 1930s and 1940s. The Saturday Evening Post, Ladies’ Home Journal, Good Housekeeping, Cosmopolitan (rather different from what it is now), The American Magazine, and many other weekly magazines ran a great deal of fiction, both short stories and serialized novels. The high-paying slick market showcased soft-boiled mysteries involving Perry Mason and Nero Wolfe and welcomed suspense fiction too. Major suspense authors of the 1940s, such as Charlotte Armstrong and Vera Caspary, would garner tens of thousands of dollars in serialization rights. On the right is the cover of Collier’s for 17 October 1942, announcing the first installment of Ring Twice for Laura, later known simply as Laura.

One more factor needs to be mentioned: the publication venues. Everybody knows that the hard-boiled tradition has its roots in Black Mask and other pulp magazines of the 1920s. What’s less often emphasized is the “slick-paper” market of the 1930s and 1940s. The Saturday Evening Post, Ladies’ Home Journal, Good Housekeeping, Cosmopolitan (rather different from what it is now), The American Magazine, and many other weekly magazines ran a great deal of fiction, both short stories and serialized novels. The high-paying slick market showcased soft-boiled mysteries involving Perry Mason and Nero Wolfe and welcomed suspense fiction too. Major suspense authors of the 1940s, such as Charlotte Armstrong and Vera Caspary, would garner tens of thousands of dollars in serialization rights. On the right is the cover of Collier’s for 17 October 1942, announcing the first installment of Ring Twice for Laura, later known simply as Laura.

As mystery genres proliferated, their popularity soared. Contrary to what historians imply, the puzzle novel with a brilliant sleuth was far from defunct. Christie’s Poirot and Sayers’ Wimsey retained their fame into the 1940s, significantly outselling Hammett and Chandler. Ellery Queen’s novels are not read much today, so it’s hard to imagine a time when over a million copies of them were in print. More generally, the public’s appetite for mystery novels and radio plays was intense. In 1940, 40 % of all titles published were mysteries, and in 1945, an average four radio shows devoted to mystery were broadcast every day, each drawing about ten million listeners.

Small wonder, then, that Hollywood came calling. Curiously, the master detectives popular with the reading public wound up in B-film series (Charlie Chan, Ellery Queen) or remained unexploited in the 40s (Nero Wolfe, Perry Mason). What came to the fore, as being more suitable for the dynamic medium of film, were the hard-boiled heroes of Hammett and Chandler. Because the rise of hard-boiled adaptations fed clearly into film noir, they have attracted the most attention. But mutating alongside them, and becoming at least as lucrative, were the films shaped by the updated Gothic and the psychological thriller. Variety noticed the trend in fall of 1944.

Plain murder as a film frightener is passé. Been done too long in the same old way. Theatregoers actually can yawn in the face of manslaughter as it’s been perpetrated for the whodunits during the past year or more. . . . The newer type of horror pictures, invested with psychological implications, deal with mental states rather than melodramatic events. . . . The typical tale in the new genre crawls with living horror, is eerie with something impending, and socks its suspense thrill well along toward the middle of the story instead of doing the crime victim in at the beginning and then building a whodunit and a detective quiz as the element of suspense.

The piece doesn’t respect today’s genre distinctions. Apart from using the term “horror” in a way we wouldn’t, the author lumps together suspense thrillers like The Lodger, Hangover Square, The Uninvited, and The Suspect; the Gothic Gaslight (“a perfect example of the new approach”); and spy thrillers The Mask of Dimitrios and The Ministry of Fear. Even Jane Eyre is included, without irony. (Surprisingly, Double Indemnity from spring 1944 isn’t mentioned.) Still, the article acknowledges that mystery had strong audience appeal and that while the classic whodunit had had its day on the movie screen, films could be given new energy by other literary trends.

Mystery as artifice

Mystery is the only genre I know that makes narrative strategies as such central to its identity. A musical, a Western, or a science-fiction saga can be presented in linear fashion, telling us everything step by step, and still retain a genre identity. But a mystery plot can’t be presented straightforwardly. The writer must manipulate plot structure and narration to some degree.

A mysterious situation or plot action is one whose causes are to some degree unknown. In the detective formula, both refined and hard-boiled: A person has been murdered; what led up to it? In the Gothic: There are sinister goings-on in the house; what’s causing them? In the suspense thriller: Someone wants to harm me; who and why? (And will I escape?) To generate mysteries, the plot-maker must suppress key information. That can be done by opening late in the story (say, after the crime has been committed), by employing flashbacks (often launched from a climactic moment), or by restricting the range of knowledge (via a Watson or a string of eyewitnesses). More subtle options involve ellipses, such as those in The Murder of Roger Ackroyd and the diary portion of The Beast Must Die (1938).

At the level of prose style, clues can be buried in descriptions or offhand remarks. The narration can creatively mislead us from the start, in the title (The Murder of My Aunt, The Murderer Is a Fox) or the diabolical opening sentence of Carr’s “The House in Goblin Wood.” And sometimes you get pure showing off. The first chapter of The Rynox Murder Mystery (1931) is entitled “Epilogue,” and the last chapter is entitled “The Prologue.” In addition, the book is broken not into parts and chapters but “reels” and “sequences,” a device creating a small meta-mystery (gratuitously, so far as I can tell.)

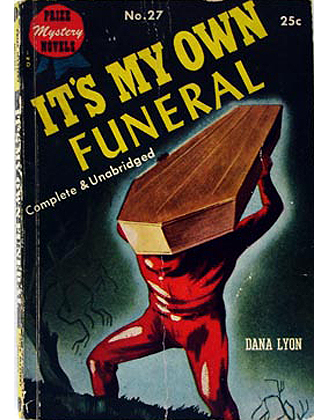

Given the proliferation and mixing of genres and the constant demand for innovation (echoed in Variety’s crack about things “being done too long in the same old way”), 1940s mystery writers were pressed to find new storytelling gimmicks. Everything had not been done, at least not yet. Historians of the detective story routinely praise the ingenuity of Christie and company in the 1930s, but the 1940s saw a positively baroque expansion of options. A dead detective pursues the investigation as a ghost. Another wakes up trapped in a coffin and starts telling us how he got there. Pat McGerr distinguished her work by replacing the question Whodunit? with others, such as: We know who’s guilty, but who’s been murdered?

Given the proliferation and mixing of genres and the constant demand for innovation (echoed in Variety’s crack about things “being done too long in the same old way”), 1940s mystery writers were pressed to find new storytelling gimmicks. Everything had not been done, at least not yet. Historians of the detective story routinely praise the ingenuity of Christie and company in the 1930s, but the 1940s saw a positively baroque expansion of options. A dead detective pursues the investigation as a ghost. Another wakes up trapped in a coffin and starts telling us how he got there. Pat McGerr distinguished her work by replacing the question Whodunit? with others, such as: We know who’s guilty, but who’s been murdered?

In the suspense mode as well, we find efforts to create novelty at the level of narration. With the emerging interest in psychoanalysis, the thriller began to probe the protagonist’s inner life and hidden traumas, producing not only the hallucinatory visions of Woolrich and Goodis but the crazy-lady divagations seen in The Snake Pit (1947), Devil Take the Blue-Tail Fly (1948), and Patricia Highsmith’s early short story, “The Heroine” (1945). As in the purer tale of detection, a great deal depended on feints and fake-outs at the level of the prose. The cleverly misleading narration of Ira Levin’s A Kiss Before Dying (1953) turns on the use of a pronoun.

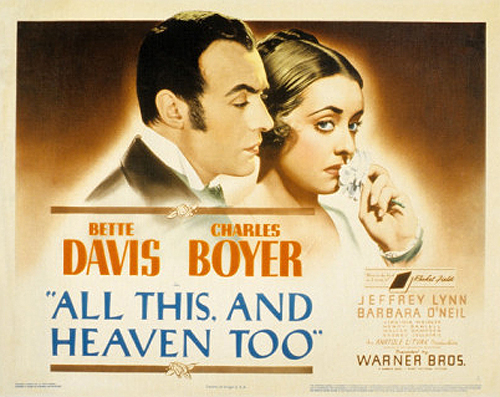

Hollywood filmmakers borrowed plentifully from the new genres, particularly the psychological thrillers that could appeal to women. Significantly, Rinehart’s pioneering 1908 novel was remade as The Spiral Staircase (1945), and Warner Brothers redid Collins’ classic Woman in White in 1948. Moreover, I think, filmmakers tried to find cinematic counterparts for the genre’s restricted narration, dream and fantasy passages, misleading exposition, and shrewd ellipses (e.g., Possessed, 1947; Mildred Pierce, 1945; Fallen Angel, 1945). The diversity of mystery fiction inspired Hollywood writers and directors to create a Golden Age of the mystery film, and the innovations of the period left a legacy for filmmakers ever since.

These genres had a wider impact too. That’s what I’ll concentrate on in my presentation, “I Love a Mystery: Narrative Innovation in 1940s Hollywood.”

The two major histories of mystery fiction are Howard Haycraft, Murder for Pleasure: The Life and Times of the Detective Story (1941) and Julian Symons, Mortal Consequences: A History from the Detective Story to the Crime Novel (1972). Both are very much worth reading, as is Leroy Lad Panek’s idiosyncratic An Introduction to the Detective Story. The best study of the 1920s-1930s puzzle tradition is Panek’s Watteau’s Shepherds: The Detective Novel in Britain 1914-1940. On A. B. Cox, see Malcolm J. Turnbull, Elusion Aforethought: The Life and Writing of Anthony Berkeley Cox.

The Variety article I quote bears the misleading title, “New Trend in Horror Pix; Laugh with the Horror.” It’s in the issue of 16 October 1944, p. 143.

Unlike The Rynox Murder Mystery, Cameron McCabe’s Face on the Cutting-Room Floor (1937) blends moviemaking and murder in a thoroughgoing, albeit wacko, fashion.

Other entries on this blog have dealt with some of my mystery favorites, especially Ellery Queen and Rex Stout.

P. S. 11 June: Mystery expert Mike Grost has kindly reminded me of his encyclopedic site, A Guide to Classic Mystery and Detection. By discussing authors both famous and forgotten, he displays the great diversity of this mega-genre.

Bette Davis eyelids

Bette Davis, ca. 1950; caricaturist unknown. From Miguel Andrade’s site.

DB here:

Janet Frobisher, mystery writer, has murdered her husband. Naturally, she telephones her lover and asks him to come over. But before he arrives, Janet finds that the runaway George Bates has come calling. George has been her husband’s partner in bank fraud, and now they’ve gone further. They robbed the bank at gunpoint, and a policeman was shot. George faces Janet and demands to know where her husband is.

Nobody is likely to call Another Man’s Poison (1952) a masterpiece, or an undiscovered auteur gem. (Irving Rapper has, however, signed some better-than-average pictures.) Like many ordinary movies, though, it can tell us some interesting things about cinema if we look closely. Especially when that look takes in Bette Davis.

I had to restrain myself from adding a soundtrack link for this entry. You know the one. The earworm may be at work already. But having you listen while you read would probably only distract from my point.

Eyeball to eyeball

That point is one I’ve made before. We humans are very good at watching each others’ eyes. Evolutionary psychologists debate how that skill might have evolved, but there’s little doubt that we can “mind-read” on the basis of others’ gaze direction and other eye-related cues. Of all the arts, cinema probably has the most powerful ability to galvanize and channel our reactions solely through the way people use their eyes.

But what’s an eye? I argued in an earlier entry on The Social Network that eyeballs as such aren’t very expressive, despite poets’ claims to see the soul there. Dilations are about all you get. The real expressive work gets done by gaze direction, the brows, and the lids. Blinks help too. Lately, watching films from the 1940s and early 1950s for a book I’m planning, I was struck by how the great divas of that era used their eyes.

Consider for example Barbara Stanwyck in the Mitchell Leisen weeper No Man of Her Own (1951). Helen Ferguson has innocently assumed the identity of the dead daughter-in-law of a wealthy family, and she’s torn between revealing her lie and protecting her baby. So in most scenes her look is intent and direct. She uses the screen actor’s usual tactics of steady gaze and motivated blinks, with brows and mouth carrying the emotional impact (below, shocked anxiety; then distress).

Even when she’s thinking, her eyeline remains steady and she doesn’t play much with her eyelids.

What about when Stanwyck is much less innocent, as in Double Indemnity (1944)? Devious as she is, Phyllis Dietrichson meets Walter Neff’s eyes squarely. “There’s a speed limit in this state, Mr. Neff.”

When Phillis isn’t looking straight at Neff, it’s when she’s pretending to be demure and concerned about her husband’s safety—and acting as coy as Brigid O’Shaughnessy in The Maltese Falcon. But once Neff sees through her effort to insure her husband, she glares at him unwaveringly.

Part of Stanwyck’s star persona is the bold woman who responds frankly to whatever is put before her. When it comes to evasive maneuvers, though, there’s Bette.

Putting a lid on it

Publicity photo for Jezebel.

Her eyes are big and can be quite round, of course. They also sit remarkably centrally on her face, thanks to her high forehead; this quality is accentuated when her hair is brushed back, as it often is. What especially interests me today, though, is her eyelids. If Bette rolls her eyes at us in those Warners publicity shots, she can also create hooded eyes that suggest she’s harboring secrets.

Bette has remarkable control of those eyelids; she can close them to a very exact degree. In performance, the slight drooping of the upper lid, combined with a small shift in her gaze and a turn of her head, can shade the line or word she speaks. Add that sullen mouth and her vocal tone and rhythm, and you get a nuanced suite of micro-emotions.

Take the moment in Another Man’s Poison after Janet Frobisher tells George that she’s killed her husband. She rushes into a two shot favoring her as George says: “You could’ve divorced him.” Her reaction is an eye-flick, evading his look but still radiating defiance.

Now begins a series of micro-movements that shift Janet’s reaction away from George. She explains how her husband kept her tied to him. “He/ was/clever”: On each word, her expression, eyelines, and eyelids change minutely. Then she pauses.

“He saw/ to that/ too” gets mapped onto three more changes, with traces of a smirk accompanying an eye-shift on the word “too.”

But Janet isn’t looking straight at George yet. She’s got more to say by way of explaining why divorce wouldn’t work: She and her husband continued to have sex. She puts it more indirectly: “He paid me”—pause when she lifts her eyes to look back at George—“visits.”

This instant of looking sharply back at George, as she had at the start of the shot, drives the point home and becomes the climax of this phase of the exchange. Eyelids, brows, chin, mouth, and gaze have all cooperated in creating an emotional detour away from and back to her questioner. Bette’s tiny side-glances show us a woman thinking and reacting to what she’s thinking, relishing what she’s going to say and then watching the effect of what she says. It all takes eight seconds.

Don’t be the wide-eyed ingenue

You can see the two stars’ technique operating very early in their careers. Stanwyck is the name star of So Big! (1932) and Davis is fifth-billed. Above, we find Stanwyck, playing the nobly suffering mother Selina, using her direct-gaze strategy (though as she ages, the eyes get a little pinched). By contrast, we have Davis as the saucy young illustrator Dallas O’Mara. Selina’s son Dirk asks Dallas why she doesn’t love him. When she answers, William Wellman’s staging gives Davis a little aria of face-time at the piano.

Dallas explains that she’s attracted to men who have confronted the rough side of life. I can provide only excerpts of what is a forty-second shot, full of shifts of head position, facial expressions, and eye movements, complete with finely calibrated eyelid work. The passage reminds us that Davis’ dynamic expressions and eye movements are often motivated by her playing characters full of jittery pep, talking fast and thinking faster. She will even deliver phrases with her eyes closed—here, speaking of men with hands scarred from work and struggle.

As she says, “You haven’t a mark on you, Dirk,” Dallas reaches across to grip his forearm. A new phase of the scene begins, but still with the suite of slight head turns and eyelid action.

Dallas says that if he’d kept on as an architect instead of taking refuge in a safe business job, his face would show it. As in Another Man’s Poison, Davis concludes her monologue by turning to face the man and deliver the final line directly. From early in the scene, however, Dirk has turned his face aside in shame.

Where would his marks of character show? “In your eyes, in your whole being.” She peers up at him, her face closer than at any other point in the scene, and her hand lifts from his arm to accentuate her frank but brutal blow to his pride.

Which makes our last view of her all the more arresting. In the final scene, Dallas meets Dirk’s mother and imagines her as an ideal subject for a portrait. Now the flighty young artist is riveted on the steady, serene gaze of the older woman.

In this climax, Dallas becomes what Dirk has called her—“a wide-eyed ingenue”—but in her rapt admiration she proves herself worthy to be Selina’s daughter-in-law.

Bette, eyeballing us

Now that we know the role Bette’s upper eyelids play, we can appreciate other moments when she milks their effects virtuosically. Go back to Another Man’s Poison. George tells Janet that he has the weapon used in the bank robbery—the pistol that bears her husband’s fingerprints. As George starts his line, she’s taking a drink in the foreground. Lifting the glass, she tips her head back too so that her eyes are just visible under her lids—and they’re looking out at us.

George says, “I’ve got the gun.” Janet lowers the glass, but she keeps it poised. Now her lids and eyelines present her reaction to George’s information that the pistol bears the husband’s fingerprints. You see her thinking about evasive action.

This moment in effect spotlights Davis’ use of her eyes; she’s frozen in place, and they’re the only things that move.

Early in the film, we’re given a sort of primer that trains us to watch Janet/ Bette’s eyelids. The first scene shows Janet making her call to her lover from a phone booth. It’s staged with her in profile, so that her brows and mouth are relatively unmoving and the eyelids, centered in the frame, become quite salient. I won’t try to follow all their tiny fluctuations, in coordination with the chin’s angle and the mouth, but these samples should give you the flavor. (Note the very slight difference between the first and the third image, and the second and the fourth).

A more frontal view of La Davis would have been a more characteristic star introduction, but it’s as if the film is saving her full-face firepower for later scenes.

There’s other evidence that Bette was considered to be able to hold a scene by an eyelash. In Payment on Demand (1951), flashbacks from Joyce and David’s miserable marriage take us to happier days. One scene shows the couple embracing on a hospital bed after Joyce has given birth to their second child.

Joyce learns of David’s plans to move out of town, but she resists and sits upright. This brings her distraught reaction home to us with the now familiar coordination of eyeline, eyebrows, and eyelids with the mouth and shakes of the head—another suite of micro-behaviors I can merely sample here.

But then Joyce relaxes and falls back, hiding her face as the camera cranes up slightly.

Director Curtis Bernhardt has reframed the shot so that as Joyce curls up on the pillow, one eye peeps out. We don’t see her mouth replying to David’s lines, but we get the customary fractional eyelid changes, as in the phone booth scene above.

Eventually Davis moves her shoulder and reveals Joyce’s mouth, but for several seconds we’ve been obliged to follow the small movements of her lids as the only clue to her calming down—and getting her way with David. This is, needless to say, all done without a close-up.

Hollywood cinema is a highly formal cinema, as conventional in some ways as commedia dell’arte. Yet that doesn’t mean it must trade only in gross effects. Admittedly, much of today’s cinema has sacrificed nuance for brute force. All the better, then, that returning to even minor films from the studio era can remind us of how many opportunities the medium affords.

Bette Davis isn’t the only virtuoso performer, of course, and many of her contemporaries show the same kind of gifts, sometimes put to different ends. She offers a convenient illustration of how film actors can cultivate meticulous control over facial regions we don’t normally think about. She makes up for being short and rather slight by playing her face like a chamber ensemble, with every “voice,” eyelids included, contributing to the restless dramatic flow.

Okay, I know: The song was running through your head all the way through. You deserve a break. Go ahead, but you might as well watch something too.

On the evolutionary implications of our eye behavior, see Michael Tomasello et al., Why We Cooperate (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2009). Tomasello argues that the need for social cooperation favored signals of shared attention; to work together, we need to notice things that other people are looking at. He also points out:

All 200-plus species of nonhuman primates have basically dark eyes, with the sclera—commonly called the “white of the eye”—barely visible. The sclera of humans (i.e., the visible part) is about thee times larger, making the direction of human gaze much more easily detectable by others. A recent experiment showed that in following the gaze direction of others, chimpanzees rely almost exclusively on head direction—they follow an experimenter’s head direction up even if the experimenter’s eyes are closed—whereas human infants rely mainly on eye direction—they follow an experimenter’s eyes, even if the head stays stationary (pp. 75-76).

But tracking my eye direction helps you, not me; how could it have evolved? Tomasello hypothesizes that making eye direction salient developed in a cooperative social environment. It’s part of social intelligence, in which mind-reading works to everyone’s benefit in shared tasks.

A vast resource on all things Bette is this site. Some perceptive remarks on her acting style are at Uncle Eddie’s Theory Corner. Jim Emerson offers an interview with Miss Davis in a smoke-filled room, while Roger Ebert presents an admiring appreciation of All About Eve.

An earlier blog entry here reflects on the performance of another sacred diva of the period, Joan Crawford. If you’re interested in a wider account that fits such matters into a broader theoretical perspective, including folk psychology, try this essay.

In cognito (we trust)

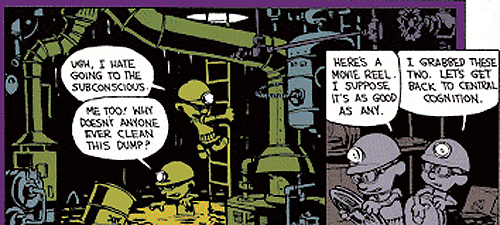

From Calvin & Hobbes, 10 April 1994.

DB here:

Every year at about this time, I trumpet the upcoming convening of the Society for Cognitive Studies of the Moving Image. This year’s powwow is held at picturesque Sarah Lawrence College, under the auspices of Professor Malcolm Turvey, no stranger to this blog. The final day of it will take place at NYU’s Cinema Studies Department. I had to miss last year’s conference for health reasons, but I’ll be there this year with a paper on 1940s Hollywood narrative.

Some earlier blog entries sketch out my take on what’s interesting about the group’s work. You can find treatment of the 2008 Madison gathering here and here; the 2009 Copenhagen event here and here with an epilogue about Lars von Trier and Asta Nielsen; and afterthoughts on the 2010 Roanoke meeting here. Last year, because I couldn’t go, I offered a web essay, here. This discusses my current thinking about the cognitive research framework.

This year, although I’m going, I’m again offering a new web essay. It’s about how models of mind (Gestalt, psychoanalytic, cognitive, etc.) have shown up in film theory and criticism. The piece is organized chronologically, and it tries to tie ideas about the psychology of cinema to a history of filmmaking: the theories I discuss emerge as responses to changes in form, style, and theme. The essay will eventually be reprinted in Art Shimamura’s anthology, Psychocinematics: Exploring Cognition at the Movies, forthcoming from Oxford University Press. Art’s collection gathers many cutting-edge essays from SCSMI members.

A sideways note: I learned recently that my old book, Narration in the Fiction Film (1985), sold 470-some copies last year. That’s a lot for an old academic study, especially one with many used copies in circulation. I infer from this (good cognitivists make inferences) that some instructors are using it in courses. I’m grateful, naturally, but I want to signal that I’ve altered some of the views I expressed in that book. If a professor is using my book to exemplify the cognitive perspective on narrative, I’d urge him or her to consider as well the web essay I already mentioned, “Common Sense + Film Theory = Common-Sense Film Theory?” In addition, my most recent answers to questions about filmic storytelling, in which narration is treated as one aspect of a larger process, can be found in “Three Dimensions of Film Narrative,” in the collection Poetics of Cinema. In other words: I hope I’ve learned something since 1985.

The week following the SCSMI gathering, UCLA is hosting Visual Narrative: An Interdisciplinary Workshop on 20-22 June. This very promising event hosts presentations and commentaries from linguists, philosophers, and a couple of SCSMI star psychologists. Dan Levin has already made appearances in this blog (notably here), and Tim Smith, Continuity Boy, has contributed our perennially popular guest entry, “Watching You Watch THERE WILL BE BLOOD.” The distinguished philosopher of art George Wilson, author of Narration in Light, will also be there. Thanks to Rory Kelly, one of the Workshop’s organizers, for tipping me off.

After SCSMI (from which, or about which, I hope to blog), we’re off to Bologna, so expect more of our usual reportage from Cinema Ritrovato, that frenzy of movies and movie lovers. Coming up next, though, there’s Bette Davis to reckon with.

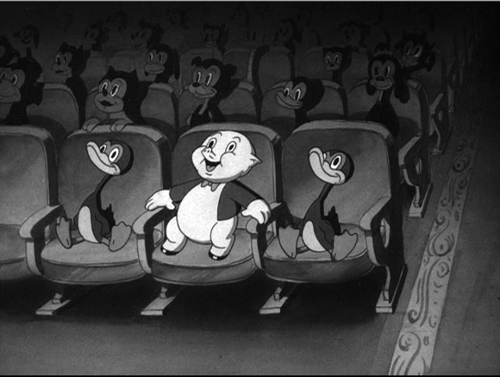

Cognition is important, but so is perception, as every front-row sitter knows. From The Film Fan (1939, Warner Bros., Bob Clampett).