Archive for 2012

TINKER TAILOR: A guide for the perplexed

Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy.

DB here:

As the final credits rolled, a man behind me blurted out, “I don’t get it.” He’s not alone. Kristin and some acquaintances have told me that they found parts of Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy hard to follow. Several critics, while praising the film (and doubtless getting more of it than that guy), have warned viewers to pay close attention. Roger Ebert said:

I enjoyed the film’s look and feel, the perfectly modulated performances, and the whole tawdry world of spy and counterspy, which must be among the world’s most dispiriting occupations. But I became increasingly aware that I didn’t always follow all the allusions and connections.

Some of the film’s admirers advise us not to worry much about the intricate storyline. Michael Phillips remarks:

This is one of the finest achievements of the year, and while it’s easy to lose your way in the labyrinth, I don’t think “Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy” is most interesting for its narrative pretzels. Rather, it’s about what this sort of life does to the average human soul.

Even if I weren’t a le Carré fan, I’d be fascinated by a film that can succeed both critically and financially and still leave its audience puzzled about its plot.

Critics of popular filmmaking claim that our movies cater to simple minds, but we actually find a lot of successful films, from Groundhog Day and Pulp Fiction to Inception, that are complex in intriguing ways. I argued in The Way Hollywood Tells It that since the 1960s one current of filmmaking has explored narrative strategies that were minor, even unheard-of, options in earlier times.

I’m not ready to join Steven Johnson in suggesting that audiences have become smarter. In certain respects older films are more demanding than contemporary ones. I’d rather say that new conventions are in force, aimed at certain sectors of the audience who are willing to put forth the effort. Ambitious filmmakers may find new ways to fulfill these conventions, balancing novelty with intelligibility. This is the path, I think, that the makers of Tinker Tailor took, and it didn’t prevent the film from earning $17 million at the US box office.

The film’s ’70s patina isn’t off-putting. The filmmakers offer deliberately grainy imagery, enveloped in hazes of rain and cigarette smoke. The palette, except for Ricki Tarr’s idyll with Irina, is grey, brown, and beige. Scenes are shot with long lenses, rack-focus, and drifting tracking shots. Zooms and push-ins are interrupted by cutaways. The result is an Altmanesque look, but more disciplined. It’s not the visual style, then, but those the narrative pretzels—another reminder of late ‘60s and early ‘70s storytelling—that attract my notice today.

So I persist: What makes the movie hard to grasp? If we can get a sense of this, we might get to know Tinker Tailor more intimately, while also producing some ideas about how mainstream films work generally. To attempt an answer, I have to go into detail. I won’t be supplying a plot synopsis, but the Wikipedia entry is reasonably comprehensive. I’ll be looking less at the story and more at the storytelling. Still, don’t read further if you haven’t seen the film. In the tradecraft jargon of blogging: There are spoilers ahead.

Breaking up the blocks

One factor contributing to the film’s difficulties, as many reviewers have pointed out, is that it’s adapted from a big and complex book. But it isn’t just the size of the original novel that poses problems. It’s the way the plot is constructed and the story is narrated.

The plot of the novel Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy (published 1974; the commas aren’t in the adaptations) consists mostly of blocks of flashbacks. The action starts long after Control has died and his old staff, including George Smiley, has retired. The novel’s first scenes show Jim Prideaux’s arrival at the boy’s school, seen from the perspective of Bill Roach, his shy confidant. We don’t yet know how Jim connects to Smiley, who after a dinner with a gossipy acquaintance, is summoned to investigate the prospect of a mole in the Circus’s top echelon.

Smiley’s investigation involves questioning witnesses like Connie Sachs, but more often it involves “burrowing,” working patiently through the files that Control had studied. Le Carré presents what Smiley gleans from the files as flashbacks, and interwoven with those are Smiley’s reflections on the key personnel and their power struggles. Institutional memory and Smiley’s rueful recollections tie together the ambush of Jim Prideaux and the vein of top-secret information code-named Witchcraft.

Respecting the novel’s construction would demand a cascade of long tales framed by Smiley’s step-by-step pursuit. Arthur Hopcraft’s screenplay for the seven-installment 1979 BBC series took the simpler option of starting with a scene that is presented very late in the novel, during Jim’s revelatory confession to Smiley. The TV series opens with Control summoning Jim and sending him off to Czechoslovakia. Jim is shot and Control is cast out. Clarifying the string of events this way, and giving us a decent action scene early on, has its cost: Smiley doesn’t enter the series for twenty-three minutes.

Since Hopcraft and director John Irwin had hours at their disposal, the scenes could stretch and breathe, and they retain the somewhat chunky, modular quality of the novel. But a two-hour film couldn’t handle the book’s plot so spaciously. What did the team of Bridget O’Connor and Peter Straughan do? Straughan explains:

The adaptation process differs from book to book, but in the case of “Tinker Tailor,” it involved a kind of mosaic work. The structure of the novel was broken into pieces. Some long sequences would remain intact – Peter Guillam stealing the files from the Circus, for example – but in other cases we would take a line or event from one place in the narrative and move it elsewhere, shifting the fragments around endlessly until it felt right. The goal was to create a new version of the narrative which would bear a close family resemblance to the source material, but have its own cinematic personality. The really difficult part was not fitting the plot into two hours but doing it without losing the tone; to give the film the same autumnal, melancholy pace, and to give the script air and silence.

The most obvious instance of this fragmentation is the repetition of the ambush of Bill Prideaux in the Budapest café. In keeping with current norms of storytelling, this scene is replayed at crucial points, each time giving us a bit more information relevant to the scenes of testimony around it.

Repetition is a luxury that can’t be overindulged in adapting a hefty novel. To spare time for the pace, the air, and the silences the filmmakers want to include, they had to be more concise in their presentation of plot. They had to chop le Carré’s big narrative blocks into bits.

When we view a mosaic we can step back to see how the composition blends all the fragments. But we have to experience a movie bit by bit. A film, we might say, is a moving mosaic, and we are usually standing very close to it. Just as important, a mosaic, made out of gaps, leaves it to us to grasp how the parts fit together—to make our mind jump the gaps.

Unconventionally conventional

How does Tinker Tailor fit the pieces together? In general, the film adheres to common conventions of modern storytelling but then subtracts one or two layers of redundancy. The little gaps created make the film seem roundabout today, when rather linear and explicit narration is the norm.

Start with a simple case. Like many modern spy films, Tinker Tailor initiates a shift to another locale by a long-shot framing, often from on high. Here’s an example from The Bourne Ultimatum.

It’s triply redundant: We see a city landscape including the Arc de Triomphe; we’re told it’s Paris; and we’re told it’s Paris, France (not Paris, Maine). Compare the parallel shot from Tinker Tailor.

Not exactly a difficult leap—who doesn’t know that the Eiffel Tower is in Paris (France)?—but it’s a little less explicit. Earlier instances are more laconic. When we’re taken to Budapest and Istanbul, probably not as immediately recognizable to many in the audience as Paris, we get a cityscape with only one mention in the dialogue to tag the setting, and no captions. Least explicit of all are the shots picking out the Circus in London.

Another film would have typed out, “MI6 HQ,” but we’re left to infer that behind this façade the Secret Intelligence Service does its work. So the convention of the exterior establishing shot is respected but made a little less redundant.

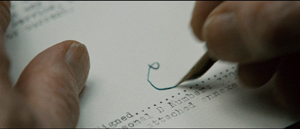

Consider as well the introduction of the Circus’s decision makers. Another film might have started with Smiley and followed him from his office into the briefing room. Instead, he’s introduced as one of several men, then as an out-of-focus figure alongside Control. And even Control could have been more clearly identified. He signs his resignation with what could become an emblem of the film’s stingy approach to storytelling.

Just as truculent is the process by which Lacon is led to summon Smiley. First Lacon gets a warning call from the field agent Ricki Tarr. So far, so conventional. But Tomas Alfredson has staged things so that Tarr is seen at a distance, turned from us, and blocked by a phone booth. Who is this guy? We must get all our information solely from his voice, not his facial expression.

Soon after Peter Guillam has entered the Circus, he gets a call. Most directors would have cut away to the caller, or at least let us hear what Peter is hearing. But we’re denied that information. On the soundtrack, we hear only a muffled, “It’s Oliver…ringing…” It’s Lacon, but you know that only if you know his first name is Oliver, and we’re teased by hearing almost nothing of what he’s saying. We know even less than Guillam, and this suppressive narration is characteristic of Alfredson’s handling of genre conventions.

Next we see Smiley at home, watching television. There’s a knock at the door. Cut to a car driving, Peter at the wheel and Smiley in the back seat. Smiley is silent, and Peter offers his regrets: “I was sorry to hear about Control, Mr. Smiley.” Earlier we’ve been given one shot of the dead Control in the hospital. So much for his backstory.

Finally, as the car pulls up at Lacon’s house, the fragments combine into an intelligible sequence when Peter says, “He said Tarr called him from a phone box.” Retrospectively, we can buckle the sequence up as a familiar genre action: The hero is called back to the battle by his chief.

Another convention, one that goes far back, is the dialogue hook. This is a bit of speech that ends one scene and links directly to the next one. Tarr calls Lacon and names Guillam as his supervisor. Cut to Guillam crossing the street and entering the Circus. Later, Smiley suggests that he and Guillam investigate Control’s flat. Cut to them entering it.

Dialogue hooks, as I’ve traced out here, are enormously helpful in guiding us through the plot. But sometimes Tinker Tailor works more obliquely. In one scene Peter reads of the staff who were sacked following Control’s fall. One is Jerry Westerby, whom we’ll meet a long while later, and the other is Connie Sachs. Cut to a train station, with Smiley buying a ticket to Oxford. It’s a hidden hook: most films would include in the earlier scene a line such as, “Connie Sachs, who’s now in Oxford.” Again, a conventional device is roughened a bit, made slightly more difficult. And sometimes the hook is visual and disruptive, as when a shot of Jim, bleeding in the Budapest arcade, is followed by a shot of the boy Bill Roach looking out a window at Jim’s arrival, as if he’s also looking down at his future teacher.

The BBC series was broadcast in weekly episodes, so recapping and backtracking in each installment helped viewers remember. At intervals we see Smiley bringing Peter up to date and briefing Lacon on current discoveries. The film flagrantly refuses to provide this conventional help. As Ebert notes:

More ordinary spy movies provide helpful scenes in which characters brief each other as a device to keep the audience oriented. I have every confidence that in this film, every piece of information is there and flawlessly meshes, but I can’t say so for sure. . . .

What replaces the standard briefing scenes? Some rather elliptical passages. There are the nodes in which Smiley reflects on the evidence. We get a shot of him staring, followed by a cascade of imagery as his mind plays with possible suspects.

Linked to the briefing scene is another convention, the board or wall on which all the suspects are diagrammatically arranged. In our visit to Control’s apartment we might have seen pictures of Bill Haydon, Roy Bland, Toby Esterhase, and Percy Alleline laid out in a rectangle, with the sinister silhouette of Karla up top, and dotted lines connecting them. Yet Control, the bedraggled chainsmoker, could hardly be so tidy. Instead, the film gives us something more in character and more oblique: a litter of chessmen, each with a picture taped awkwardly on. Eventually Karla is revealed as another piece (the powerful white Queen). On his own, Smiley joins in Control’s conceit and tapes a picture of the new suspect Polyakov to a bishop.

Le Carré’s novel tied the suspects together with a verbal emblem, based on the child’s nursery rhyme. It linked the boy’s school to the Circus. But the film doesn’t introduce the tinker-tailor motif until very late. Instead the chess pieces visualize the multiple-choice problem, but in a ragged, haphazard way that suggests that perhaps Control really was, as Jim Prideaux suspects, going mad. More broadly, the imagery (with the briefing room as a gridded checkerboard) reminds us that spying, known for decades as The Great Game, is now a global chess match. It pits Karla against Smiley—whom Control has identified as the black Queen.

George the Obscure

Again and again, the script and Alfredson’s direction invoke a convention only to make it more difficult to grasp. The central examples involve Ann, the faithless wife. She isn’t just treated elliptically; she’s suppressed. Instead of showing her flirting with Bill at the Christmas party, we see only the back of her head and Bill looking past Smiley’s shoulder.

In a later flashback to the party, Smiley looks out the window and sees Ann in the garden. Another film would have shown us who’s clutching her in the foliage, but this film leaves it to us.

Of course many viewers will know Ann’s partner is Bill, but another film would have confirmed this more explicitly. Instead another standard scene is handled in a glancing way. More generally, Ann’s phantom presence not only makes her seem remote, like a princess in a tower, but sets her off against the blonde Irina, the maiden to be rescued in Ricki Tarr’s story. Thanks to the camera and a compact mirror, Irina’s face gets the caresses another film would devote to Ann.

Irina, beautiful and sincere, holds the film’s major secret, the one that initiates Smiley’s investigation. She harks back to the blonde mother who is in the line of fire in the Budapest arcade, and that shooting prefigures Irina’s fate.

The crowning achievement in the film’s laconic way with conventions is the climax in the safe house. Smiley has arranged for Ricki to send a message that will force Karla’s mole to make an emergency appointment with his connection Polyakov. There Smiley, Guillam, and Mandel will record the meeting and capture the double agent. In the BBC series, this climax runs over eight minutes, built out of crosscutting and suspenseful waiting. Smiley and Guillam burst in together and a quick pan shot reveals Bill as the culprit.

The film uses suspense and crosscutting as well, but the sequence consumes only six minutes. More important, by switching our attachment away from Smiley at the crucial moment, it conceals his entry to Bill and Polyakov. Instead we follow Guillam separately into the house, up the stairs, and to the parlor. There he confronts the aftermath of what might have been a heroic confrontation. Climax is treated as anticlimax.

Jim Emerson, in a nicely honed piece, suggests that we think of such passages as not so much elliptical as economical. I want to have it both ways. The scenes are economical because they fulfill familiar narrative and genre-based functions: We know how to fill them in. Yet they’re also elliptical because they hold back information, sometimes a little and sometimes a lot. A mosaic can show us familiar people and things, but it also asks us to make extra effort to see the pattern emerge. The tesserae fit, but the bumps and grooves between them are palpable.

It may be that art films have always tended to be self-consciously wrought genre films. L’Avventura: A mystery-melodrama. Blow-Up: A detective story. Drive: the thinking person’s action film. If so, then Tinker Tailor is the smart Bourne movie. Creative novelty needs a familiar base to play off. Movies come from other movies, and originality can take a tradition, even a popular one, as a point of departure for innovation.

Best watcher in the unit

Once plot gaps have alerted us, we should expect things to proceed through hints. Granted, there are hints that can’t be picked up unless you know the novel. For instance, the film doesn’t stress the fact, emphasized in the novel, that Bill is an amateur painter and the canvas he brings Ann on the fateful night is one of his own works. It’s the picture that Smiley is studying at the end of the credits sequence, as if the film’s two primary antagonists are already squaring off.

But, sticking just to the hints we can pick up without the novel, the film is fairly rich. It invites multiple viewings, as many movies do nowadays, in order to catch the undercurrents or the things that flash by too quickly on the first pass. (If we want to find more, we can buy the DVD.) I can’t pretend to exhaust the possibilities, but here are some that strike me.

Go back to those chessmen. As we’ve seen, the two antagonists, Karla and Smiley, are made parallel as the rival Queens. Three suspects are assigned to innocuous pieces: Percy as the white Rook, Toby as the black Knight, and Roy as the black King (although that assignment might be a narrative feint, hinting that Roy’s the traitor). But Bill is the white Bishop, and in retrospect we can see the fact that Smiley makes the Moscow agent Polyakov a black Bishop is a pointer to Bill’s guilt—and maybe a suggestion that, as Bill will say, George knew all along.

Or take the homosexual element. One question that comes up in conversation after the movie is whether Bill and Jim were lovers. It’s treated as a possibility in the original novel and becomes stronger as the film proceeds, especially after Bill—in a moment of privileged information for the audience—pockets a picture of the two friends embracing and laughing. By the end, in the final flashback of the Christmas party, Bill rouses the loner Jim and flashes him a smile; but the brandy glass he floats away with seems intended for Ann. Bill’s bisexuality is explicit in the epilogue when, in the compound, he asks Smiley to pay off both a girl and a boy. More than a hint, as well, is the tear that dribbles down Jim’s cheek as he executes his friend. (Bill’s wound, rhyming with Jim’s perforated back in Budapest, again recalls the slain mother in the arcade.)

Similarly ambivalent is the presentation of the dapper Peter Guillam. He’s introduced turning his head to watch a cute young lady pass. Later he’s revealed to be gay: for security reasons, he has to break up with his partner. In retrospect, we can see the shot when Bill and Peter eye the new clerk Belinda as presenting two double agents, each one passing as a lady-killer.

More minor touches hint at the sexual undercurrent. Bill on the phone: “And I said you may fuck me but you still have to call me sir in the morning.” It takes a quick eye to spot another manifestation of the motif. Polyakov, posing as a cultural attaché, writes articles for a bilingual magazine. After Connie has told her tale, there’s an insert—an excerpt from Connie’s memorabilia, or perhaps only a memory of Smiley’s—of an article signed by Polyakov, which says of the Russian Ballet corps:

To see them only in a narrative ballet would be to know them incompletely. The programme shows a perfect cross section of their accomplishments.

They can dazzle us with a technique that seems to defy the laws of gravity but that is not merely acrobatic because it is truly gay in expression.

Like the dancers, Bill and Jim are both athletes and acrobats, powerful and graceful. I can’t prove this implication was intended by filmmakers, but by chance or design, it’s a fragment that fits.

Or take the Christmas party. There the tune, “The Second-Best Secret Agent in the World” ramifies outward to several second-besters: that night Jim is Bill’s second-best lover, Smiley is Ann’s second-best lover, and Smiley is the agent outwitted, at that point, by Bill. Another hint: At the height of the evening, the USSR anthem is sung ironically by the Circus staff, while Bill, an undercover Soviet, is off in the garden. Not to mention that as Control signs his retirement papers, he asserts: “A man should know when to leave the party.”

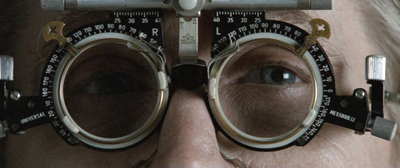

Above all are the eyeglasses. Promoted in the film’s publicity (when Oldman found them, he found the character), they become associated with seeing things as they are. The old hornrims seem to be something of a shield; Smiley pushes them back into place after he sees Bill with Ann. But once Smiley has gotten his new, more powerful pair after leaving the Circus, he uses them as an instrument of scrutiny. They enlarge his vision eerily; often they’re lit and in focus when his eyes aren’t. And they hide his eyes from others.

Although he bears Bill’s name, the podgy boy Roach is a closer parallel to Smiley. For him and for George, spectacles are a sign of wary vigilance. Jim praises Roach: “Best watcher in the unit, I’ll bet. As long’s he’s got his specs on, aye?” The motif may come from a passage in the novel that is recast for the film. Bill tells Smiley that Karla had worried that Smiley would catch him.

Karla said you were good—the one we had to worry about. But you do have a blind spot. And if I was known to be Ann’s lover, you wouldn’t be able to see me straight. And he was right—up to a point.

But those were the old glasses, and Smiley was a more vulnerable man then.

Saint George?

The novel is based, as most people know, on the revelation back in 1963 that a cadre at the center of the British Secret Intelligence Service was in the pay of Moscow. Kim Philby was the central figure, surrounded by Donald Maclean, Guy Burgess, and “the fourth man” identified later as art historian Anthony Blunt. In a scathing introduction to a 1981 book on the conspiracy, le Carré diagnoses the scandal as symptomatic of an endemic weakness in Britain’s ruling class. (Yes, he uses that phrase, which no American politician dares to utter.)

Was he not born and trained into the Establishment? Effortlessly he copied its attitudes, caught its diffident stammer, its hesitant arrogance; effortlessly he took his place in its nameless hegemony. . . . The SIS quite clearly identified class with loyalty.

He might be describing Bill Haydon:

Philby, an aggressive, upper-class enemy, was of our blood and hunted with our pack; to the very end he expected and received the indulgence owing to his moderation, good breeding, and boyish, flirtatious charm.

Worse, the agency that was pledged to protect Britain had insulated itself from reality, somehow seeing in an American-promoted anti-Communism a small rebirth of the Raj.

Whatever went on the big world outside, England’s flower would be cherished. “The Empire may be crumbling; but within our secret elite, the clean-limbed tradition of English power would survive.”

Le Carré’s lacerating remarks remind us that he might be our only major popular novelist who has held uncompromisingly critical positions on international affairs, including the Iraq war and the growth of American militarism and corporate power.

But the polemicist isn’t identical with the novelist. Tinker, Tailor provides a far more ambivalent picture of betrayal. Le Carré the polemicist has created in Haydon a perfect embodiment of what he despised about British Intelligence and the class system that feeds it. The parallel world of the boys’ school evokes the origins of the corrosive ethic that led to Bill’s treachery.

Yet the novelist spares his traitor the worst. For one thing, Peter Guillam, who idolized Haydon, can’t summon up condemnation.

Despite his banked-up anger at the moment of breaking into the room, it required an act of will on his own part—and quite a violent one, at that—to regard Bill Haydon with much other than affection. Perhaps, as Bill would say, he had finally grown up.

Smiley, who has every reason to hate Bill, is at a loss. He mulls over how he should judge the man who has done such monstrous things. As a friend worthy of respect who stood by his convictions? As a committed thirties intellectual? As a romantic elitist clouded by ideology? As an esthete who elevated his distaste for Philistinism to a political principle? As a superficial man in the grip of a compulsion to betray?

Smiley shrugged it all aside, distrustful as ever of the standard shapes of human motive. He settled instead for a picture of one of those wooden Russian dolls that open up, revealing one person inside the other, and another inside him. Of all men living, only Karla had seen the last little doll inside Bill Haydon.

In the book, Smiley’s uncertainty about Bill leads him to hope for a reconciliation with Ann. For him, unlike Bill and Karla, love isn’t an illusion or cover story. In the TV series, for all his triumph over the Alleline cadre and Karla’s mole, he returns to Ann and her chiding: “Poor George, life’s such a puzzle to you, isn’t it?” But the film gives us a different Smiley, and it interprets his reward quite differently.

We can approach the problem through performance. The TV series makes Smiley a stern schoolmaster, keeping his own counsel but voluble, thanks to the fluting of that Guinness voice. His facial expressions work a narrow range, but are very nuanced within that compass. Here is Guinness shifting, minutely, from polite approval to a steely comprehension while his oblivious informant chatters on.

By contrast, as every critic has noted, Oldman’s Smiley is virtually blank for most of the film. His frog-mouth, half-open or clamped shut, remains impassive. Guinness lets us into Smiley’s mind as he interrogates his targets, but Oldman’s most marked reactions are brow-wrinkling concentration and puzzlement. The high point, George’s discovery of Ann’s disloyalty, elicits only a gasp and a gape (and a pushing up of the glasses). As usual, even that reaction is muffled a bit, this time by the profile angle.

Similarly, everything conspires to make George obscure. Framing, setting, and lighting put him far from us, wrap him in shadows, let reflections on his spectacles block his eyes.

Guinness’s Smiley isn’t hard to read, once you tune to his high, narrow frequency, but Oldman’s Smiley is a sphinx. And it seems to me that this poker face works toward a new conception of Smiley’s role. The elliptical narration conspires with Oldman’s performance to create a conclusion that is far more harsh than what we find in the book or the series.

Early on, the film shows us George shamed. Control, forced to resign, announces that Smiley will leave with him. It evidently comes as a surprise to Smiley, who—in a moment that many critics have rightly praised—turns his head slightly and after a beat and a blink accepts with a tiny nod. For the rest of the film, George’s head-turns will be his principal signal of surprise, uncertainty, or sudden realization. (It’s even contagious: his adversaries execute the same gesture, and even Guillam catches the habit.) Smiley and Control stalk out of the Circus as exiles and part on the sidewalk without a word and Smiley comes home to an empty house.

Summoned back into service, he launches his investigation. In a key scene in the novel, the series, and the film, he confides to Peter his meeting with Karla long ago, when he tried to persuade the Russian to switch sides. The meeting disclosed a faultline in Karla’s character (“He’s a fanatic, and the fanatic is always concealing a secret doubt”), but it revealed Smiley’s weak spot too. Asking Karla to think of his wife, Smiley betrayed his worries about Ann. Karla retained the cigarette lighter that Ann had given Smiley, a token of Smiley’s fear of losing her. Years later, cuckolded by Bill at Karla’s behest, Smiley adds sexual shame to professional disgrace.

There’s a certain mystery about how the movie Smiley cracks the case. In the book and the series, there’s a lot more evidence about the mole than we get in the film. In the turning-point sequence, subjective montages lead to a burst of images and recurrent lines from Ricki: “Everything the Circus thinks is gold is shit.” Smiley is convinced there really is a mole, chiefly because of Jim Prideaux’s testimony, but we have to reason on trust: the reappearance of Karla and the murder of Irina before Jim’s eyes connect the mission to Budapest with the Witchcraft files.

The TV Smiley reveals his reasoning in a very lengthy interrogation of Toby Esterhase. Over fifteen minutes, Smiley builds a plausible case and forces Toby, to avoid suspicion that he’s the mole, to reveal the location of the safe house. Lacon is briefed offscreen, and George is given permission to set the trap.

But the film Smiley acts very differently. He confronts Lacon and the Minister and bluntly announces that there’s a mole, that Karla controls him, and that SIS has been feeding the Americans trivia and lies. He offers no evidence. The officials are shaken solely by Smiley’s uncharacteristic vehemence. His mocking conviction smashes their resistance and they give him permission to go after Toby.

With Toby, Smiley again uses brute force. No reasoning, no evidence, just the bald threat of throwing Toby onto the plane and shipping him back over the Curtain. Cringing and whining, Toby gives up the safe house’s address, and George can proceed to set the trap. And this comes after the moment when Smiley, knowing full well that Irina is dead, promises Ricki to do “his utmost” to retrieve her. Guinness’s Smiley makes the same promise, but in his gentleness we sense a man pained by his bad faith. Oldman’s Smiley is as guarded as ever.

I submit that the Smiley of the film, once he has overpowered his superiors, can’t spare a moment to brood over Haydon’s personality. He proceeds largely from a vindictive, controlled aggression. Lacon fired him, Alleline despised him, Toby insulted him, and Bill betrayed his marriage. Behind that severe blankness, I think, burns a desire to avenge Control, and to get a bit of his own back. When that mask slips, in talking with Lacon and the Minister, he’s nearly gloating.

The film, in sum, seems to me to offer a legitimate reinterpretation of the Smiley character. His fierce anger is rather close to le Carré’s attitude toward Kim Philby: The man may have been an enigma, but he was still despicable. The difference is that while le Carré can castigate the man in print, George can pay his traitor back. In this dirty game, he can finally checkmate Karla.

Was it worth it? The novel leaves you wondering. In its final pages, Smiley moves toward uncertain reconciliation with Ann. Jim’s future is more hopeful: after killing Haydon, he returns to the school and rebuilds his relation with young Bill, the other “new boy.” The only hope, it seems, lies in human relationships, not in a frigid bureaucracy.

But in the film, Jim harshly breaks off with the boy, and Smiley triumphs. To the music of “Beyond the Sea,” the losers—Ricki, Connie, Bill—are glimpsed. But Smiley, having kept his own counsel throughout, is a winner. There’s little sense here of le Carré’s distaste for the institution that nourished Bill and his breed. Smiley reenters the Circus, in a smart new suit and topcoat, striding to the top floor and taking Control’s seat, to offscreen applause. (I grant you there’s a bit of irony in that sound effect.) And how else to explain the vignette before that when, after the death of Bill Haydon, Smiley comes home to find Ann there? The sailor of the song has returned to the woman who has been waiting for him. Beggarman has gotten what Ricki saw in Irina: Treasure.

In preparing this entry, I was much helped by James Schamus and Khaliah Neal of Focus Films. Thanks also to Jeff Smith and Kristin for conversations about the movie.

For more on the film’s artistic approach, see Jean Oppenheimer, “A Mole in the Ministry,” American Cinematographer 92, 12 (December 2011), 28-34 (apparently not available online). After explaining that DP Hoyte van Hoytema and Alfredson sought “a grainy, somewhat colorless look,” the article reports van Hoytema saying that the zoom shots were modeled on 1970s ones: “When I look at films from the ‘70s, I like the fact that the zooms are so functional and solid. They have a beginning and an end.”

Le Carré’s introduction may be found in Bruce Page, David Leitch, and Phillip Knightley’s The Philby Conspiracy (Ballantine, 1981). Valuable studies of le Carré’s work include Peter Lewis, John le Carré (Ungar, 1985) and Michael Denning, Cover Stories: Narrative and Ideology in the British Spy Thriller (Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1987). In an earlier entry I offer an appreciation of the second book in the Karla trilogy, The Honourable Schoolboy.

Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy: John le Carré in right foreground.

PS 1 March: In a followup entry, I explore other aspects of Tinker Tailor.

Hand jive

The Magnificent Seven.

DB here:

In the long trailer for The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo, Rooney Mara as Lisbeth Salander makes a gesture to show that her fabulous memory has recorded the documents Blomkvist wants her to read over. She raises her hand toward her head and flicks her spindly forefinger.

It reminded me of how important gestures are to film performances, and how comparatively rare they are today. One feature of what I’ve called the contemporary intensified continuity style is a reliance on tight facial shots, so that actors work more with their eyes, eyebrows, and mouths than with other body parts. This solves one perennial problem actors have: What do I do with my hands? But it does cut off a lot of expressive possibilities. When filmmakers used more medium and long shots, actors could use all their equipment—stance, bearing, knees (as in The Cary Grant Crouch), elbows (The Cagney Cocked Elbows), shoulders. And arms, and hands. Nowadays if actors want to activate their hands in a dialogue, they usually have to lift them to their faces because the director hasn’t provided a looser, more distant framing.

I’ve already shared some thoughts on eyes (and argued that they aren’t as expressive as we usually think), eyeblinks, and sleeves. I’ve written about hands before, and Tim Smith has tested some of the things I discussed. Now I’d like to write about two of the best hands in the business. Before I do, though, let’s look at some simpler cases.

Handiwork

Rooney/Salander’s finger flip is a one-off, a staccato gesture that communicates instantly. It reminds us that she is, for all her cybernetic genius, rather nonverbal. Her dialogue is laconic, her face impassive. The gesture comes and goes like a keystroke. If there are air-quotes, this is an air-period.

Something more emphatic happens in Wuthering Heights, as you’d expect from (a) the more extroverted emotion of the tale and (b) the fact that the owner of the hand is matinee idol and occasional ham Laurence Olivier. Early in the film, Lockwood is staying the night in Heathcliff’s dismal mansion. He tries to close a shutter, and finds the windowpane already broken. He’s startled by what he hears (“Heathcliff! It’s Cathy!”) in the stormy night. He also thinks he sees a phantom woman. Unnerved, he pulls his hand back through the pane and stares at his trembling fingers.

This occurs in the frame story. Later that evening Lockwood is told of the tragic romance of Heathcliff and Cathy, and we get an extended flashback. Cathy yearns to join the high-flown elite in the neighborhood and is about to go out with Edgar Linton. In her petulance Cathy calls Heathcliff a stable boy and a beggar with dirty hands. Heathcliff stares down at those hands (“That’s all I’ve become to you, a pair of dirty hands”), before he slaps Cathy with one, then the other, crying, “Well, have them, then—have them where they belong!”

He stumbles from the room in a mixture of anger, shame, and confusion. Coming down the stairs he confronts Linton, who has just arrived to pick up Cathy for the party. Heathcliff stands awkwardly on the stair, his hand held at an angle, as if it’s something he’d like to slough off.

Back in his stable loft, Heathcliff smashes his fists through a window, in the manner of the broken pane that Lockwood will discover in the frame story.

Later Heathcliff, now wealthy, returns to the neighborhood. When he visits Cathy, who’s now married to Linton, he initially hesitates to shake hands with his old rival. It’s a beat long enough to remind us of the class difference marked in a pair of hands.

For a more unstressed example, consider The Magnificent Seven. Throughout the movie Steve McQueen invents hand business with the apparent aim of stealing every shot he’s in. At the very start, poor Yul Brynner is trying to be the brooding main attraction, ominously lighting a cigar. But Steve is making us watch him by shaking shotgun shells against his ear and then holding his hat up against the sun.

Soon afterward Steve sets a whisky bottle precariously on a fence post while Yul is acting seriously serious. Then McQueen has the nerve to fiddle with his hat so that Yul can no longer ignore him.

Much later Steve faces down Calvera’s outlaw band and strides into the foreground, back to us.

In such a setup, the actor who turns away is traditionally ceding the audience’s attention to the frontal players in the distance. Not Steve. Once he gets into place, he swivels just a bit and swings his hand behind his gun belt. (That instant surmounts this entry.) Then he tucks one finger in his hip pocket in the lower right corner of the shot.

If Tim Smith ran an eye-scanning experiment on this shot, my hunch is that a fair number of his subjects would watch Steve’s digits.

Hands down

McQueen’s scene-grabbing reminds us that once a filmmaker has framed the performer from fairly far back, judicious use of the hands can activate areas of the frame we normally don’t watch. After all, in most shots the upper half carries the most information, especially with respect to the actors’ bodies. My favorite example of highlighting a lower corner remains a shot from Kriemhilde’s Revenge (above). The director, Fritz Lang, laid out his frames with the precision of an engineer.

Even in a less exactly composed shot, slight hand movements down the frame can add gradation of emphasis. Smash-Up: The Story of a Woman presents some hard-boiled poker players forced to listen to a radio song that interrupts their game. They sit still, but their fingers stir a little, suggesting their impatience to get on with playing.

Now we’re moving into the area I described earlier this fall as scenic density. Several of my examples there involve small gestures. To take another instance, here’s Mercedes McCambridge in her Oscar-winning performance in Robert Rossen’s All the King’s Men. As tough campaign strategist Sadie Burke, she’s trying to explain to Willie Stark (Broderick Crawford) that he’s running as a dummy candidate for the very men he opposed at the start of his political career. (The whole movie will remind any Wisconsiner of what our Governor and his pals have been up to lately.) The scene pivots around drinking, and the saliency of Sadie’s hands is heightened by the fact that the men’s hands aren’t used at all.

After she pours herself a drink, Sadie tells Willie he’s been framed, holding her glass at her waist.

She walks away to the right, then turns and says that Willie is “the goat.” She sets her glass down at the far right of the shot.

She steps toward him and leans on the chair, tipping forward.

Jack Burden (John Ireland) steps to center frame and says that’s enough. But she presses in on Willie, saying his egotism has made him blind. There’s a cut to a tighter framing as Sadie faces Willie in profile.

She turns away, mocking Willie, and yanks the speech out of Jack’s typewriter.

She steps left to the foreground and pauses, momentarily abashed by her attack on the man she loves. Her hands do something below the frame line.

Stepping back and turning away from us, she lets us concentrate on Willie. He quietly asks Jack, “Is it true?” As Sadie shifts her position, she raises her arm and we see she’s pouring another drink.

Jack replies after a pause: “That’s what they tell me.” As Willie hangs his head, Sadie’s hand emerges at the bottom of the shot to offer him the drink she’s poured. A more assertive director would have cut to a big close-up of Willie and the proffered glass, but here the information slides into a rarely used area of the frame. The Kriemhilde trick, we might call it.

Willie takes it, and Rossen cuts to a low angle on all three, with Jack and Sadie watching the key gesture: Willie, a teetotaler, downs the drink.

Now the only hand visible is his, and the narrative momentum has passed to him. He’ll change his tactics and crush his handlers.

I can’t resist a more recent example of a similar strategy. In Mysteries of Lisbon, Raúl Ruiz keeps fairly far back from his players, filming many scenes in a single distant shot. Even when he breaks the scene into shot/ reverse-shot, he can isolate gestures in the full frame in ways that echo the handwork in Kazan (and in the work of other directors, particularly in the 1910s). Elisa de Monfort, quietly mad with vengeance, calls on Eugénia, the wife of her hate/love object Alberto de Magalhães. In the opening setup, Elisa sweeps in to wait for Eugénia, setting a purse on a distant end table. (The action is quite marked on the big screen, but might be missed on video; this is the price the modern director pays for using long-shots, I guess.)

At the end of the conversation, Ruiz cuts back to the main set-up. Because of Eugénia’s position, the purse nestles in the sort of slot that we find at the bottom of the frame in All the King’s Men above. Elisa rises and goes to pick it up, her gesture highlighting it.

It contains the eighty thousand francs she is trying to return to Alberto, a love pledge he has been refusing. Elisa picks it up, then drops it back to the table, defiantly leaving it for him.

By now I’d again bet that Tim Smith would find our eyes fastened on this tiny bit of the screen. Hands point us to props, and close-ups may not be necessary.

All hands on deck

I’ve praised Henry Fonda’s handicraft earlier on this site (and in Film Art: An Introduction). Maureen O’Hara said of him: “All he had to do was wag his little finger and he could steal a scene from anybody.” But to see his long fingers and fluid wrists at full stretch, put him in a combo. There’s a remarkable six-minute scene in Mister Roberts that lets Fonda (playing Roberts), William Powell (as the ship’s doctor), and Jack Lemmon (as Ensign Pulver) make beautiful music. I can’t go through it all, but let me mention some high notes.

Roberts wants to give the crew a day’s liberty, and to that end he’s bribed a port officer with a bottle of whisky he’s been saving. But Pulver, a lecherous layabout, has convinced a nurse to come to the cabin he shares with Roberts, and he’d planned to seduce her with the Scotch. So to help Pulver out, Roberts and Doc will concoct fake Scotch with ingredients they have at hand.

As I work it out, Powell supplies gravitas, a steady ground bass of minimal, exact gestures. Lemmon, playing Pulver as wound much too tight, punctuates his passive role with nervous head movements and stabbing arms. He supplies percussive accents. Fonda’s relaxed but severe playing, neither stolid nor spiky, is the melody that floats through it all.

At the start, after the older men have entered, Pulver is slouching, Doc is wiping off sweat, and Roberts is looking for his monthly letter requesting transfer.

As Doc replaces his hat, Roberts stresses his explanation about the whisky with a quietly tapping forefinger, a gesture you can hear on the soundtrack.

When Pulver realizes that the sacred bottle is gone, he jolts into activity, frantically pointing, as if in amplified imitation of Roberts.

Throughout the scene, Pulver will echo Roberts’ gestures, as when the senior officer lays his arm across his belly.

This mirror-effect is tied to the larger dramatic dynamic: Pulver looks up to Roberts, but his selfishness keeps him from being anything like his model. In the film’s last scene, however, he will become the new Roberts.

As Roberts and Doc decide to help Pulver, they give virtually silent-film renditions of the concept, “planning and preparing.” Powell roles up his sleeves, and Roberts claps his hands and then rubs them together as if hatching a plot. Hand-rubbing will be his refrain through the rest of the scene.

No actors under age fifty today, I think, would dare this sort of straightforward stylization. Here’s something to do with your hands, cast members.

When Doc requests a Coke to add to their ethyl alcohol, Pulver yanks a bottle out from his mattress and thrusts it across the CinemaScope frame.

Doc adds the Coke with surgical precision. All eyes are on his hands, while Roberts’ hands are out of frame.

Pulver is still skeptical and sits back down on his bunk. The dramatic impetus passes to Fonda, whose long forefinger rests meditatively under his nose: Thinking personified.

Fonda has to shift his hand in order to remark that Scotch has always reminded him of iodine. But what other actor would rotate his wrist and stick his thumb under his eye as he says that line? Try it yourself, and I bet you find it awkward. He executes it smoothly.

Without having to get up, Roberts reaches back into the medicine chest and pulls down a bottle of iodine. He passes it to Doc and signals the handoff with a little flourish.

Earlier we’ve seen Doc do the mixing as a solo performer, in the over-the-shoulder shot shown above. As Doc blended the stuff in other framings, Fonda kept his hands below the desk top, giving Powell the stage. But now we get two for the price of one: Powell’s meticulous adding of a drop of iodine to the brew, Fonda’s revisiting his calculating hand-rubs.

Fonda’s slightly out-thrust tongue is a grace note.

Pulver tries to sample the blend, but Doc beats him to it. “We’re on the right track!” he declares. Doc asks Roberts what else he’s got and Fonda, in a beautiful medium-shot with eye-catching colored medications arrayed before him, mimes the act of mulling over the next ingredient. His hand flits gracefully over the bottles and jars.

They settle on hair tonic for a touch of ageing. Again Doc adds the ingredient with precise pouring, and now he prepares for Roberts to test it. Into the frame come Fonda’s hands.

To accentuate the climax of the scene, Roberts rises to take the drink, forestalling Pulver.

Roberts clears his palate, then drinks it, pinky extended, as daintily as a lady at a party.

He stares at the glass, swallowing. Then Fonda’s hand lowers out of the frame so as to let us concentrate on his expression. His strangled line tops the whole comic arc: “You know, it does taste a little like Scotch.” Now his face does the work.

All three players are reintegrated into a master shot: patient Doc, frantic Pulver, and stalwart Roberts as they realize they’ve succeeded. Pulver, after lunging with his characteristic abruptness, finishes the glass in a hunched-over gulp.

“Smooth!” he yelps.

You might argue that such hand jive is rather “theatrical,” and perhaps some of the business came from Fonda’s three years in the Doug Roberts role on Broadway. Even so, it has clearly been recalibrated for the cinema. Theatre taught actors how to use their hands, but cinema gave them further lessons, and film directors learned to choreograph hands in relation to framing and shot scale.

My discussion doesn’t exhaust the scene, but I hope it suggestst how choices about staging and performance can make hands carry story information and express character. They can add nuance to a moment; they can surprise us by slipping into and out of visibility; and they can inflect a facial expression or line reading. If filmmakers today lock their framing on facial close-ups and moving lips, they’re depriving us of some beautiful music.

P. S. 18 January 2012 (from Midway, Utah and the Art House Convergence): Thanks to three alert readers. First, Adrian Martin spotted an orthographic error, now corrected. Second, David Cairns of the indispensable Shadowplay) writes of scene-stealing in The Magnificent Seven:

You do know what Yul said to Steve? “If you don’t stop playing with your hat, I’ll take off my hat, and then we’ll see who they’ll look at.”

And from James Benning, with the laconic message: “Here’s another.”

I wrote about Jim’s related project here.

P.P.S, 20 January 2012: This entry’s title, as many readers noted, referenced the great Johnny Otis song “Willie and the Hand Jive.” Today Ethan de Seife writes to tell me that Johnny died the day before my blog was posted. So take it as not only an homage but a valedictory.

Mr. Roberts.

Pandora’s digital box: From the periphery to the center, or the one of many centers

A laserdisc of The East Is Red; a VCD of Peking Opera Blues.

DB here:

On my first visit to Hong Kong in early 1995, one of my missions was to acquire video copies of all those HK films I wanted to study. The VHS tapes I’d seen in the States had grimy images and pan-and-scan framing. So, armed with my credit card, I focused on a higher-end format, the laserdisc.

For those too young or too sequestered to know this format, I should explain. A laserdisc was twelve inches in diameter, the size of a vinyl LP record, and coated with aluminum. A movie’s image track was inscribed optically on the disc, while the soundtrack was encoded digitally. The disc held about fifty minutes per side in the standard format, but some discs held less because they encoded the film exactly shot for shot. In that encoding system (called CAV), a still video frame was one film frame; the next still was the next actual frame. This was great for a frame-counter like me.

In the US, laserdiscs were for sale, but Hong Kong ones typically weren’t. They were a popular rental format, though, and you could use them to make nice tape copies. Needless to say, neither laserdiscs nor video tapes had copy protection.

As I made the rounds during my trip, I persuaded many shops to sell me some LDs, unfortunately for me at rather high prices. Although rentals remained brisk, the shopkeepers knew that LDs were on the way out. One charming young lady at Laser People, in Causeway Bay, told me of a new format they were waiting for. It would use a blue laser. Was it going to be as good as LD? I asked. She grinned: “Much, much better.”

On the same trip I met the LD’s downmarket cousin.

VCD = Very Curtailed Definition

Video Compact Discs (VCDs) were 4.8 inches across, flimsy, and cheap (US$4 for a legit one, much less for a bootleg). They could be played on computers or dedicated players. On the VCD format I found a copy of Peking Opera Blues, one of my favorite HK movies and one that was elusive on LD. So I bought it, along with a basic player.

The results were pretty feeble. Since the VCD was a CD-ROM, it could carry only about sixty minutes of video, at MPEG-1 compression. So a film was typically squeezed onto two discs. (Sometimes it was trimmed to fit.) Improvements were made over the years, but at a resolution of 352 x 240 pixels, the picture quality was hardly better than VHS tape. In a way, the image was more annoying than VHS because it tended to go very blocky and jerky. Some VCDs were letterboxed, but that compromised picture quality even more, since there were fewer lines devoted to the image.

Want some measure? Just above you find a VCD image from Peking Opera Blues, compared with an image copied (on photographic film) from a 35mm print. Sandwiched between the two, just for fun, is a frame grab from a recent Hong Kong DVD. (For more on these images, see the end of this entry.)

Debuting in 1993, the VCD was the answer to a film pirate’s prayers. VHS bootlegs degraded with each generation of copying, but digital video enabled every copy to be identical to the source disc. The pressing plants that manufactured music CDs could pump out VCDs en masse. By 1998 China had over 500 VCD companies and produced twenty million players per year. By 2000, players were in about a third of urban households. It became identified with low-end, Asia-centered piracy.

In the early 2000s, I saw boxes of VHS tapes chucked out onto the Hong Kong streets, and films were being released on DVD and VCD simultaneously. Piracy turned to the DVD, with results even more massive than with VCD. The newly affluent Chinese could afford the slightly costlier pirate DVD.

Meanwhile, the clumsy and heavy laserdisc was gone, preserved and on the shelves of fanatical, or just plain stubborn, collectors like me. The arrival of affordable DVD players in China in 1999 somewhat cut the interest in VCD, but recent releases today still come out on the junior format. In Hong Kong, VCDs outsell DVDs at a ratio of three to one, and titles older than a year or so go for US$3. VCDs rent more briskly than DVDs, at a cost of less than one dollar US.

Historically, I think, the VCDs played an important role. VCD made commercial movies available on a digital platform aimed at consumers. Invented by big Western companies, it was pushed aside in the rush to make the DVD the international standard. In addition, with the emergence of digital cinema, we might take the VCD as an emblem of a side pf the digital changeover that we often ignore. In surveying the results of opening Pandora’s digital box, we can’t neglect the ways that a triumph of Western research gets turned to ends that undercut the nations and companies originating it.

16mm: Digital exhibition’s dry run

Cinema has a long history of repurposing exhibition formats. A striking example is 16mm film. Invented by Eastman Kodak in 1923, 16 was suited to amateur moviemakers and news photography. Since the stock was non-flammable, 16mm films could safely be exhibited at home, in schools, in public meeting places, and in the newsreel theatres that sprang up during the 1930s and 1940s. The format was also used in screenings for the armed services. After the war, schools and community centers bought 16mm projectors, many from military surplus. My college film society had a pairs of 16mm JANs (Joint Army-Navy) machines, hulks that look like they could survive a torpedo attack. (See above.)

Throughout the 1950s and 1960s, no public school was complete without 16mm projectors for screening educational movies, cartoons, and uplifting Hollywood features. At the same time, local TV stations broadcast from 16mm prints bought from the studios. These prints became sought-after by collectors, a group whose membership expanded with the rise of 16. The format became the standard for independent and experimental filmmaking, of course, but we tend to forget that it was also the bedrock of nontheatrical exhibition. In those days, Audio-Brandon, Contemporary Films, Janus, and other companies could actually make money circulating 16mm films.

For the US and Western Europe, with few exceptions, 35mm was the standard theatrical format, but other countries were more adaptable. The data on 16mm penetration of theatrical markets are very sketchy. (See the end of this post for more information.) Still, we have some bits of evidence. In 1961, Hungary reported having over 3600 16mm installations, as opposed to 803 35mm ones. In the same year, Romania claimed only 462 35mm screens and over 3100 in 16mm.

It seems that sectors of Asia relied heavily on 16mm. As late as the 1980s, India reported over 4500 16mm installations (as opposed to 8221 35mm venues) and Korea claimed nearly 400 (significantly more than its 280 35mm screens). The proportions are probably higher in countries like Thailand and the Philippines, where commercial entertainment films were made in 16mm.

With the expansion of 16mm, a format aimed for home, school, church, and other specialty situations was repurposed for a general public. “Nontheatrical” became theatrical.

The same thing happened, more clandestinely, with videotape after the 1970s. In large cities throughout Asia you could buy or rent bootleg VHS copies of Hong Kong and Indian movies. And there was no restraint on where you could show them. Throughout what was still called the Third World, video copies were exhibited in public venues, from town squares and pubic halls and to tour buses and work sites. Asian cities boasted “video parlors” and “video clubs” and “MTV parlors,” where friends could assemble in small rooms to drink, snack, flirt, and watch a movie, often a pirated Hollywood one.

This unofficial exhibition circuit is acknowledged in the warning that preceded many videos circulated in Asia.

The copyright proprietor has licensed the film (including its soundtrack) comprised in this Video Disc (including Laser Disc) for private home use only. All other rights are reserved. The definition of private home use excludes the use of this Video Disc at locations such as clubs, coaches, hospitals, hotels, motels, oil rigs, prisons, and schools.

Which is the same as admitting that tapes and discs were widely shown in clubs, coaches, hospitals, oil rigs, and other venues.

Much more recently, this “peripheral repurposing” of home technology for public use was taken to its logical conclusion in Nigeria. In 1992, local filmmakers began making VHS films for direct sales to customers. The market expanded with the rise of digital technology, and by 2008 production companies issued dozens of new releases on VCD and DVD each week. A few single-screen and multiplex facilities have been built to show Hollywood films on 35mm, but local movies are still largely screened at home and in informal public venues like restaurants and video halls using TV monitors rather than projectors. A $200 million dollar film industry emerged from technology designed for nontheatrical exhibition.

Overshoot and good enough

A stall selling Thai VCDs in Kowloon City, Hong Kong; from CNN Go.

The VCD fit smoothly into this pattern of low-end distribution and exhibition. But that wasn’t what Western firms had in mind when they invented the digital disc.

In 1993, JVC, Sony, and Philips created the Video CD. A year later the Hollywood majors announced that they would back a single standard for high-quality digital video. The companies laid down demands as to length (135 minutes per side), picture quality (better than laserdisc), compatability with high-quality audio systems, and, among other criteria, content protection. As usual, two major rivals emerged, but they were reconciled. Patents were pooled, and after more wrangling about copy protection the DVD more or less as we know it made its debut at the end of 1997. After more fixes, the format took off in 1999, aided in no small measure by the DVD release of The Matrix.

It seems to me that Western firms’ concentration on the DVD and the sidelining of the VCD exemplify what management analysts have come to call “overshoot.” In the theory of disruptive technologies pioneered by Clayton Christensen, established firms aim to sustain an existing technology, either through incremental improvements or radical innovations. As the technology improves, these sustaining firms target the upper end of the market. Thus Eastman Kodak strove to improve its film stocks to satisfy and win the approval of the world’s top cinematographers. Likewise, Sony and other firms collaborated to create the DVD as an improvement on broadcast video, VHS, and laserdisc.

But in the process they left lower-end markets behind. Entrenched sustaining technology tends to be complicated, inconvenient, and expensive. Christensen posits that the big firms’ overshoot often leave space for firms that develop technology that is cheap, convenient, and “good enough” for what might be a very big segment of purchasers. To the professional eye, VHS was inferior to Beta tape and laserdisc, but for most consumers that tape format was good enough. Then DVD proved more convenient—smaller, more portable, easier to use—and of noticeably better quality. Experts knew that the DVD was still a compromise format, especially compared to 35mm, but for consumers it was good enough.

Overshoot encouraged the spread of the VCD. Concentrating on the DVD and its MPEG-2 protocol, Sony and its co-developers licensed the downmarket format to Asian companies. It was clear that the Chinese market, massive though it was, couldn’t afford DVD players and discs. (In 2000, China’s per capita income was about $1500; a cheap DVD player cost about $200.) But local entrepreneurs rushed to expand the low end of the market. Shujen Wang, in her very informative book Framing Piracy: Globalization and Film Distribution in Greater China, explains that it was easy for Chinese manufacturers to convert audio CD players into VCD players, thereby undercutting the imported models. By 2000, a China-made VCD player cost $30. As a further incentive, some makers included up to 100 free VCDs with purchase of a player.

Millions of players were sold in the mid-1990s, and many were installed in what Variety called “illegal video projection rooms that had screened pirated videos and movies not previously shown in China.” By 1994 there were more than 150,000 public video venues showing tape, laserdisc, and VCDs in the mainland. The following year, piracy was reckoned at a stunning 100% of the market.

Probably Western companies couldn’t have satisfied the market in Asia; local manufacturers, distributors, and retail outlets were needed to make the sales happen. So it probably wasn’t simple neglect that made VCD a de facto regional standard. Nonetheless, the VCD became a disruptive technology. For Asian consumers, laserdiscs were too expensive, VHS was comparatively inconvenient, and digital discs and players suddenly became much cheaper. And with so many movies, mostly illegal, available on the format, the buyer’s and renter’s choice was simple.

VCD was good enough–not just for private consumption but for public exhibition. Once film exhibition on tape had become widespread, the VCD made that practice far more feasible. It provided something like the world’s first “digital cinema” experience.

I’m not competent to trace the VCD’s fortunes in other countries, although it proved popular in India and Latin America. In cities and towns, entrepreneurs set up “electronic cinemas”–that is, video parlors or auditoriums screening discs, usually pirated, to paying audiences. A 1999 report in Variety Deal Memo notes:

Electronic cinema is nothing new in emerging countries with dilapidated or non-existent conventional film projection cinema infrastructure. Small-scale mobile electronic cinemas have set up in small towns for years. . . . Cinetransfer International, for example, offered rural areas in Mexico electronically-screened Mighty Joe Young, A Bug’s Life, The Water Boy, and other films over the years.

Once again, the nontheatrical becomes theatrical, but this time aided by digital technology.

Good enough is better than what we had?

From the rise of the VCD and later the DVD, it’s only a short step to digital exhibition as the West might recognize it. Again, Asia played a key role. Initially, the Western digital cinema projection standard was 1.3K resolution (1280 x 1024 pixels). This became a bone of contention. A Variety article from 2002 asks the disruptive-technology question: “How good a picture is good enough to replace film?”

One end of the spectrum says, ‘Let’s do it now. This is good enough,” says Charles S. Swartz exec director and CEO of USC’s Entertainment Technology Center, which tests digital cinema systems. “At the other end, they’re figuring out the theoretical best we can do and want to hold off.”

While filmmakers in the West debated whether 2K was good enough, exhibitors in developing countries didn’t hold off. In Brazil, small cinemas and chains began adopting 1.3K projection. In India, UFO Moviez and E-City Digital installed low-resolution projection systems in hundreds of theatres, often fed by satellite. Many local observers considered these video displays worthwhile improvements on the battered prints and faded arc-lamps that were staples of most village screenings. Now good enough was better than what went before.

Through the early 2000s, China and the US led the world in digital screens, most on the 1.3K format. The US leaped ahead in 2005, when the Digital Cinema Initiatives standardized 2K resolution. But China will pick up velocity because it’s opening new screens daily. From 2009 to 2010, China leaped from 1788 D-screens to 7920. At the current rate China is opening five new screens each day. You will not, I expect, find a piece of 35mm film in any of them.

In China and India, despite some movement toward 2K projection, the “good enough” strategy persists. Many domestically made Chinese films are released in 1.3K versions, and some are even shot in .8K (1024 x 768 resolution). These can’t be encrypted, and so pirates are making the most of the situation. Even television channels show pirated copies of local movies. And India’s major supplier of digital projection, UFO, works with the MPEG-4 codec used in Blu-ray. This has caused complaints from viewers, but the company’s managing director claims, “In a market with ticket prices averaging between Rs 10-50 [US$.20-$1.00], there is no way DCI standards will take off in India.”

It’s worth remembering,then, that movie viewing on the “periphery” was digital before digital was cool. The swift rise of digital exhibition in China, India, and other major markets has led Hollywood down the same path. You might recall the techno-nerd’s prophetic line in David Byrne’s True Stories: “The world is changing. And this is the center of it right now. Or the one of many centers.”

Much of the information above comes from the indispensable IHS Screen Digest. Other sources, not available online as far as I know, are “Electronic projection rollout excites, worries cinema industry as cost, quality, retrofit issues loom,” Variety Deal Memo (5 July 1999), 5-8, and “Country Profile: China,” Variety Deal Memo (11 October 1999), 5-8. I’ve mentioned Shujen Wang’s valuable book in the text, but go here for her 2003 paper on digital piracy in China.

See also Hu Ke, “The Influence of Hong Kong Cinema on Mainland China (1980-1996),” in Fifty Years of Electric Shadows, ed. Law Kar (Hong Kong International Film Festival, 1997), 164-178, and Darrell William Davis and Emilie Y. Y. Yeh, “VCD as Programmatic Technology: Japanese Television Drama in Hong Kong,” in Feeling Asian Modernities, ed. Koichi Iwabuchi (Hong Kong University Press, 2004), 227-247. A Google Reader version of the latter is available here. In Playing to the World’s Biggest Audience: The Globalization of Chinese Film and TV, Michael Curtin goes beyond technology and analyzes other market forces affecting VCD.

For basic historical and technical information on digital formats I always turn to Jim Taylor, Mark R. Johnson, and Charles G. Crawford, DVD Demystified, 3rd ed. (McGraw-Hill, 2006). Useful reports on the progress of VCD appeared in The Economist here and here. I talk a bit about the rise of digital exhibition in China and Hong Kong in Planet Hong Kong, available here. For background on current VCD trends I’m grateful to a friend in Hong Kong who wishes to remain anonymous.

My comparison of VCD, DVD, and 35mm isn’t entirely fair to the digital formats. Frame grabs tend to look worse than an image displayed on a video monitor, and an HDMI display of the VCD and DVD improves them. Moreover, the Hong Kong DVD isn’t particularly well-authored. A Blu-ray of Peking Opera Blues that I’ve ordered hasn’t yet arrived, so I will update this entry with a frame from that when I can. Finally, my 35mm frame enlargement is a bit too warm and could use some adjusting. But to keep comparison reasonable, I didn’t apply Photoshop to any of the images shown here.

It’s hard to know how widely 16mm film was exhibited commercially around the world, but some indications are given in Statistics on Film and Cinema 1955-1977 (Paris: Unesco, 1981) and various editions of the UNESCO Statistical Yearbook. A pleasant video devoted to JAN 16mm projectors is here; I grabbed a shot from that video above, so thanks to maynardcat for posting the footage.

Why are oil rigs singled out as targets of pirate screenings? My guess: Many Asians emigrated to work on oil extraction throughout Northern Europe and the Middle East, and it wouldn’t be far-fetched to assume that videos were screened for them on site. If anyone reading this can confirm, deny, or nuance, please correspond.

Clayton M. Christensen’s influential formulation of the theory of disruptive technologies is in The Innovator’s Dilemma (orig. 1997). Thanks to Jim Cortada for discussing these ideas with me. Volume 2 of Jim’s Digital Hand trilogy remains the best guide to how computers transformed the media landscape.

“Things fall apart. It’s scientific.” True Stories (1986).

Pandora’s digital box: At the festival

Of the thirty-three titles I saw at the Toronto International Film Festival this year, only nine were projected on 35mm film. The rest were shown on HDCam or Digital Cinema Package. At the first TIFF I attended in 2002, I saw a comparable number of films and all were projected on 35mm or 16mm film.

Jim Healy, Director of Programming, University of Wisconsin–Madison Cinematheque

DB here:

Do you complain about ads before movies? In the Digital Age you can expect more of them because there will be ads for the theatre’s projector and server and even the financing agent that supplied them.

The most aggressive preshow attraction, which I saw before every digital screening at this year’s Vancouver Film Festival, is the one promoting Dolby servers. Play when ready.

A dirty film countdown leader explodes into sleek digitalia, alchemizing cinema into the four elements. Photochemical imagery can’t bear trial by fire and is annihilated Terminator-style. But the flames are extinguished by earth (flowers), air (blue vapor) and icy water. McLuhan said film was a hot medium, but does that automatically make digital cool?

Take the clip as a victory dance. By September, when I saw the Dolby Armageddon trailer, things had already tipped. Digital projection, the immediate future for multiplexes and for small-town houses, has become a festival mainstay too. But the problems are more marked on the fest scene than in commercial venues. If you visit a festival and there’s a hiccup during a screening, count to ten before hollering. The staff, already overstretched, is facing something far less tranquil than the concluding frames of the Dolby ad–something more like the hellfire frames you see at the start.

Screener savers

Screener for Target (Alexander Zeldovich. 2011).

Films get into festivals two ways: By being invited or being submitted blind. A programmer might invite a film solely on the filmmaker’s reputation. For instance, every festival wants the next Wong Kar-wai film (assuming he ever finishes it), and you would probably accept it sight unseen. More often the programmer catches the film at another festival, or in a private screening, or in a privately circulated video copy. That first viewing might be on any format. If the filmmaker submits the work, it will typically show up on a DVD copy, called a “screener.” Some festivals prefer the film to be uploaded to the site Withoutabox. The selection committee watches the submission to make an initial decision about the work.

Members of the press who attend a festival can usually get a look at some of the films via screeners. Often local critics watch screeners, especially if they have to write a review in advance of the festival and they’ve missed a press screening. Visiting programmers also borrow screeners from the festival because they usually can’t see all the films they might want to.

The problem is that screeners tend to be of wretched quality. Burned to DVD-R, sometimes from a VHS tape, and often in the wrong ratio or anamorphically squeezed, they are usually garnished with a more or less prominent watermark, either a “property of” one or simply a timecode readout chattering away. I can’t imagine claiming to have seen the movie after watching the typical screener. Kristin and I have used them to pull frames for our blog entries when we visit festivals, but only after we watch the films in projection.

Screeners look shabby by design. Anything approaching the finished film in image quality will be pirated, and the watermark announces that the dub you bought from the blanket on the street is stolen. I have seen a screener assigned to a particular person, his name as a caption throughout, so the distributor will know whom to pursue if it’s leaked.

Screeners made it much easier for filmmakers to afford to submit work to many festivals; imagine what costs were like in the days before videotape, when films were sent out on prints. But the emergence of screeners, I think, cheapened the film. VHS tape and many commercial DVDs make movies look ugly, but DVD screeners are far worse. Nonetheless, they are a fixture of the festival scene. As with so much about digital video, we can’t go back.

Digitalis

Sony HDW-D1800 HDCam deck. List price: $45,045.

Screeners are watched mostly behind the scene, treated as tools for programmers and critics. What about the things the audience sees?

For commercial projection in your local ‘plex, Hollywood companies realized that a proliferation of digital standards was bad for business. So they set up the Digital Cinema Initiative, which established specifications for the Digital Cinema Package—the ensemble of files packed onto that matte silver brick that is replacing traditional film rolled up on reels. The DCP files are encrypted and opened up with passkeys that are supplied separately. The DCP plays 2K or 4K digital video on the two standard projection systems, the DLP one established by Texas Instruments and the SXRD one established by Sony. It’s Microsoft vs. Apple all over again: the DLP format is licensed to several projector manufacturers (Christie, NEC, Barco) but the Sony format is used only on Sony machines.

Besides the DCP, there are many other digital formats for displaying moving images. Erik Gunneson, a filmmaker and teacher here at the University of Wisconsin—Madison, ran through some of the most common ones with me. They’re distinguished by many factors, but two common measures are resolution and compression. The more lines, the higher the resolution; the less compression, the better the image (although some compression is inevitable in any digital video projection.) Many of these are capture formats—that is, means of recording—that are also used for playback.

The earliest to emerge were the DV formats, all consumer/ prosumer platforms. They use “standard definition” video codecs, as opposed to High Definition ones. There’s a bewildering number of DV cameras and playback devices, because Sony and Panasonic developed different improvements on the basic standards (720 x 480 resolution). The most common versions, Mini DV and DV Cam, use tape for capture. They are fading out in independent filmmaking, but some festivals still screen in these formats.

Home viewers are probably most familiar with the DVD, which in the NTSC standard uses MPEG-2 video compression at 720 x 480 resolution. On a large screen, your typical DVD is unsightly. Blu-ray discs, of course, look better, partly because of their higher definition (as high as 1920 x 1080 resolution).

At the professional level, you have several options, mostly provided by Sony: Betacam SP, an analog format, and Digital Betacam, known as DigiBeta. They use tape, not hard drives, to record image and sound. But they’re falling into disuse now because of the rise of HDCam. It can use either tape or optical drives as recording media. HDCam playback can through up-sampling yield standard HD images of 1920 x 1080 pixels, and this makes it a popular option for independent filmmakers. PBS documentaries are often shot on HDCam.

There’s also HDCam SR, which yields, as they say, “native” 1920 x 1080 resolution and audio features. The SR format was initially designed for high-end special effects (bluescreen/ greenscreen) and became allied with Panavision in the creation of the Genesis camera. SR is sometimes used for television series. As you’d expect from a studio-based format, it’s expensive. According to Sony, an HDCam SR system runs about $230,000, and a 124-minute blank cassette (the same engineering as the old Sony Beta cassette) costs about $424.

Many of these formats come in various flavors: PAL or NTSC, anamorphic or unsqueezed, progressive or interlaced, recent upgrade or older specs, settings for various frame rates, and on and on. And there are still other recording and playback formats, such as HDV, DVCPro, and D5 HD . When talkies came in, maybe there were as many competing sound systems floating around alongside the two studio standards. But back then, there weren’t film festivals.

Format flare-ups

Sony J30SDI Compact Betacam Player; plays Betacam, Digital Betacam, Beta SP et al. Price: $21,000.