Rebooked

Monday | January 28, 2013 open printable version

open printable version

3/60 Baum in Herbst (Kurt Kren, 1960). Hand-drawn soundtrack.

DB here:

It’s time again to write up books that fate and friends have sent my way. And I do mean books, as in printed matter on paper held together by string and glue and wrapped in a decorative cover.

Nothing against e-books, mind you. I’ve put out a couple myself (see right sidebar), and I’ve become more inclined to use them for my research. Every academic sometimes needs to read only parts of a book–a chapter that touches on your project, a bibliography that can help you, chatty footnotes that can suggest a new idea. If your library hasn’t got a copy and Inter-Library Loan is difficult, an e-book can be worth the investment. The only real problem is the prospect of buying, in any format, a book that you must read but that you know will be dire. (Names and titles omitted for the sake of the new year’s mood.) Then at least the e-book, being less expensive, can mitigate the pain of paying, if not of reading.

Direness isn’t on the agenda for the books I have on the desk today. All are worth your attention, in whatever format you can get them.

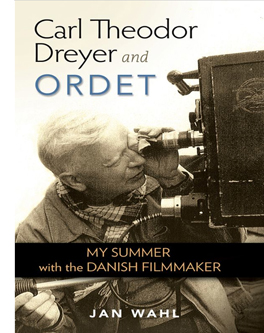

Before Jan Wahl became a prolific writer of children’s books, he left the US to study in Denmark. There he had the great fortune to be a dogsbody for Dreyer on the making of Ordet. Wahl left the country after the exterior shooting, but he kept in touch with Dreyer for some time afterward. His daily notes of their conversations were vetted and corrected by Dreyer, in hopes of eventual publication. Now, nearly sixty years later, the book has arrived.

Dreyer took a shine to the young Fulbright student and confided to him ideas about his earlier work and his plans for his Jesus film. Dreyer was at that point fairly undecided about many aspects of the Jesus script, including how to end the story. But these are sidelights compared to the central action of Wahl’s memoir, the making of Ordet in the cloudy and rainy summer of 1954.

Despite the inhospitable weather, Dreyer planned and shot much more action in exteriors than appeared in the final film. The film’s hermetic “theatricality” seems to have been arrived at through pruning landscape images and shots of characters coming and going. An especially intriguing shot of Anne and Anders meeting in a field took a great deal of time:

Despite the inhospitable weather, Dreyer planned and shot much more action in exteriors than appeared in the final film. The film’s hermetic “theatricality” seems to have been arrived at through pruning landscape images and shots of characters coming and going. An especially intriguing shot of Anne and Anders meeting in a field took a great deal of time:

Anne sets out to deliver a pair of trousers for her father, Peter Tailor, but she takes the long way around in order to have a tryst with Anders. The lovers meet in the field, lingering at a corner in the rye.

The camera had a long traveling movement, its tracks laid on a wooden platform in the shape of an immense letter L whose angle was parallel to the field. On that day, between three and five o’clock there was sufficient light for five takes. . . .

We’re also reminded of Dreyer’s fastidiousness—arranging sheep in ranks around the Borgen farmhouse and demanding that 1925 newspapers should line the drawers in the household. (Seeing a recent paper would “break the spell of concentration should an actor happen to see it.”) It’s a pity that Wahl could not stay through the whole production, which moved to the Palladium studio in the fall, to provide more details like this.

Just as ingratiating are Wahl’s accounts of the village where the film was shot, a tiny place taken over by Dreyer’s project. Wahl lingers over hearthside meals in a land where coffee has almost sacramental significance.

“There is something about coffee that soothes the Danes,” [Dreyer] said, “and puts them in touch with God. . . . On the winter days, which last so long here in Jutland, a warm cup is a balm; they take everyday communion in it.”

The primary value, I think, of Carl Theodor Dreyer and Ordet lies in atmospheric moments like these. I’ll always remember Wahl’s portrait of the gentle but obstinate Dreyer at sixty-five: dreaming of a film on Christ, smoking cigars, and tossing pastry crumbs to the bird that visits his garden every afternoon at three-thirty.

Pop quiz, hot shots:

What firm had the initial idea for VOD rentals? (Hint: Not Netflix.)

What firm had the initial idea for video kiosks? (Hint: Not Redbox.)

The answers, along with a solid story, can be found in Netflixed: The Epic Battle for America’s Eyeballs. Gina Keating’s brisk business reportage pits upstart Netflix against the well-entrenched Blockbuster in a cage match worthy of its title. Keating starts by demolishing Reed Hastings’s tale that he conjured up the service when he was annoyed by late fees on Apollo 13. In fact, tech entrepreneur Hastings entered the start-up as a fairly passive money guy, while the more retiring Marc Randolph devised the Netflix business model, which included what Keating calls an “intuitive user interface and peerless customer service.”

Keating shows how Randolph’s idea for an online video store on the Amazon model tapped into the expansion of internet retail. Randolph, according to Keating, “had what it took to conceive and launch Netflix. What came next—ruthless optimization and relentless growth—were not his strong suits.” By 2002, Randolph had left the company and Hastings ruled.

In counterpoint Keating chronicles Blockbuster’s ups and downs, mostly downs. It was already feeble when Netflix launched, and Viacom was perpetually trying to unload it. The decline was evident, however, in 2007 with the coming of CEO Jim Keyes, who had turned around 7-Eleven. Keyes decided to try to make Blockbuster outlets into “full-service entertainment destinations” where, according to Keating,

In counterpoint Keating chronicles Blockbuster’s ups and downs, mostly downs. It was already feeble when Netflix launched, and Viacom was perpetually trying to unload it. The decline was evident, however, in 2007 with the coming of CEO Jim Keyes, who had turned around 7-Eleven. Keyes decided to try to make Blockbuster outlets into “full-service entertainment destinations” where, according to Keating,

. . . customers would drop in for pizza and a Coke, or buy a book or a flat-screen television or hang out with their kids on weekends while waiting for a movie to download.

It was at this point that the Onion posted its YouTube video of the Living Blockbuster Museum. Still, Blockbuster should be credited with seeing the future of VOD. Execs tested it in 2001 (answer to Question One), but the concept had to wait until Internet access widened and download speeds picked up.

Netflix made missteps too. The firm let the staff who developed the video kiosk concept depart and form Redbox. (Answer to Question Two.) Hastings was also caught off-guard when Blockbuster Online began to surpass Netflix’s customer base. Still, you come away largely admiring the adroitness of the company. I hadn’t realized the power of Netflix’s software innovations, especially its recommendation engines.

Netflixed concentrates on major players, but Keating does introduce many economic-structural factors to provide higher context. And concentrating on personalities makes for a gripping read. Hastings, who declined to be interviewed for the book, is depicted as a math-mind who could inspire software engineers but who dealt coolly with human feelings in a way reminiscent of Steve Jobs. Carl Icahn, who stalks through many other histories of modern US media, has his moments too, mostly ones of fulmination.

Non-fun fact: A 2005 survey indicated that only 22% of Americans preferred to see a movie in a theatre rather than at home on video. And this was before the surge in VOD.

Netflix treated the Sundance Film Festival as a venue for dealmaking and PR. This is just one measure of the importance of such events for film as an art and a business. For decades our bookshelf devoted to film festivals harbored only a few volumes, mostly official histories of Cannes and Venice. By now, however, “festival studies” has become a teeming area of research. This is all to the good. International film culture after World War II, as we pointed out in Film History: An Introduction, has depended centrally on festivals, and film historians have to realize that these gatherings shape the history of cinema in many ways.

Netflix treated the Sundance Film Festival as a venue for dealmaking and PR. This is just one measure of the importance of such events for film as an art and a business. For decades our bookshelf devoted to film festivals harbored only a few volumes, mostly official histories of Cannes and Venice. By now, however, “festival studies” has become a teeming area of research. This is all to the good. International film culture after World War II, as we pointed out in Film History: An Introduction, has depended centrally on festivals, and film historians have to realize that these gatherings shape the history of cinema in many ways.

Jeffrey Ruoff’s new volume, Coming Soon to a Festival Near You: Programming Film Festivals, gathers several essays about the principles and pragmatics of deciding what’s shown. As Ruoff claims in his introduction, festivals perform many functions: they “celebrate film as an art, affirm different kinds of identity via film, [and] facilitate the marketing of films.”

Given these missions, the programmer functions minimally as a critic who aims to satisfy the audience’s tastes while steering it in novel directions. But the programmer can also be a celebrity in him- or herself, making the festival an extension of the programmer’s tastes, as happens with Michael Moore (Travers City), Roger Ebert (Ebertfest), and Tony Rayns’ Asian selections at Vancouver. This is what Ruoff calls the programmer as auteur.

The programmer is also a historian—reviving work from the past in retrospectives, while acting as a kind of future historian, laying down the conditions for later development in cinematic sensibility. The praise awarded to Bergman and Antonioni at 1950s and 1960s European festivals created a narrative of artistic development that historians who followed would elaborate.

Coming Soon to a Festival Near You offers a potpourri of pieces, from academically inflected accounts of festival history to personal memoirs from programmers and critics. Focus Features producer James Schamus provides a pungent entry on the economics of red-carpet galas, and Bill Pence, a long-standing fest entrepreneur, recounts the development of Telluride. All in all, Ruoff’s volume helps us understand the role of festivals as tastemakers and gatekeepers of world cinema.

“It is a country, culturally speaking, that respects its avant-garde filmmakers, present, past, and future,” writes Adrian Martin. He’s describing Austria, from which comes the magnificent volume Film Unframed: A History of Austrian Avant-Garde Cinema. Peter Tscherkassky, a major filmmaker himself, has created a collection that manages to be at once sweeping and in-depth. Many of us (but not enough) know work of the “old” masters Peter Kubelka and Kurt Kren, but this anthology skips back to the early 1950s. There we find artists like Kurt Steinwendner, whose Der Rabe (The Raven, 1951) looks to be a stark exercise in neo-Expressionism, done to electronic music.

“It is a country, culturally speaking, that respects its avant-garde filmmakers, present, past, and future,” writes Adrian Martin. He’s describing Austria, from which comes the magnificent volume Film Unframed: A History of Austrian Avant-Garde Cinema. Peter Tscherkassky, a major filmmaker himself, has created a collection that manages to be at once sweeping and in-depth. Many of us (but not enough) know work of the “old” masters Peter Kubelka and Kurt Kren, but this anthology skips back to the early 1950s. There we find artists like Kurt Steinwendner, whose Der Rabe (The Raven, 1951) looks to be a stark exercise in neo-Expressionism, done to electronic music.

As the chapters move toward the present, some names and films were familiar to me, most were not, but all emerged as intriguing and provocative. The diverse directions of experimentation are traced by some of our best writers (Maureen Turim, Jonathan Rosenbaum, Steve Anker, Andréa Picard, and Christoph Huber, among others). The hefty volume is filled out with color photographs and many pages of -graphies: bio-, filmo-, and biblio-.

Martin’s foreword, from which my initial quotation comes, sets the stage for a comprehensive reappraisal of this major tradition. We have to thank the film collective sixpackfilm and the Austrian Film Museum, which has become a leader in publishing books and DVD editions that mightily expand our horizons. Thanks also to the government subsidies that allow the book to be available at a very decent price. Next up, one hopes: A big fat DVD compilation.

In the fall of 1988 there materialized at my office an elvish man with a neat white beard and a Compaq laptop. He was perpetually smiling, and he soon revealed why: he had one of the quickest wits and sharpest senses of humor I’d encountered. The Lilly Endowment had awarded him a year’s grant to improve his knowledge of film. Very sensibly, he came to UW.

The faculty all welcomed him, and he became friends with Kristin and me. Tapping away quietly on his laptop, sitting on the far side of the front row (to keep plugged in), he took the most extensive and precise notes on my blahblah that I have ever seen. Recalling those days, I have to smile when I realize that the oldest person in the class was the only one who brought a computer. His notes circulated in samizdat among the grads for years.

His name was Peter Parshall. A film fan from his youth, Pete had taught film and literature at Rose-Hulman Institute of Technology. He became famous as a beloved, highly demanding teacher: the student slogan was “Peter Parshall picked apart my perfect paper.” After his year in Madison, Pete went on a Fulbright Award to teach American film at the Technical University of Dresden. He retired from Rose-Hulman some years ago but kept active (bicycling, especially) and still teaches film courses.

His name was Peter Parshall. A film fan from his youth, Pete had taught film and literature at Rose-Hulman Institute of Technology. He became famous as a beloved, highly demanding teacher: the student slogan was “Peter Parshall picked apart my perfect paper.” After his year in Madison, Pete went on a Fulbright Award to teach American film at the Technical University of Dresden. He retired from Rose-Hulman some years ago but kept active (bicycling, especially) and still teaches film courses.

Now Pete has published a probing book on a broad storytelling strategy that goes by many names—thread structure, hyperlinked plots, network narratives. Altman and After: Multiple Narratives in Film provides incisive analyses of several films, while also offering an illuminating set of categories for understanding them. Nashville is a “mosaic narrative,” an effort to surrender forward-driving plot in favor of fragments that pull the characters into teasingly incomplete patterns. Network narratives, with intersecting and culminating plotlines, are exemplified by Pulp Fiction, Amores Perros, Code Unknown, and The Edge of Heaven.

A new and intriguing category is the “database narrative.” Here the film launches a set of events but then replays them differently, providing alternative pathways for events. Sometimes this strategy is motivated as reflecting different points of view, as in Rashomon. But other tales question the very solidity of the narrative world, as in The Virgin Stripped Bare by her Bachelors, Run Lola Run, and The Double Life of Véronique.

Pete’s book has already received praise, with Sarah Kozloff noting in Choice: “For several of these films, Parshall’s discussion is the best analysis available, and teachers and students have much to learn from his searching intelligence.” Altman and After is a fine addition to the growing list of books seeking to understand the permutations of today’s cinematic storytelling.

Torkell Saætervadet, a Norwegian expert on film technology and cinema design (and on aviation!), won our thanks with his authoritative 2005 text The Advanced Projection Manual. Now the International Federation of Film Archives, which co-sponsored the earlier volume, has brought out his new FIAF Digital Projection Guide.

Torkell Saætervadet, a Norwegian expert on film technology and cinema design (and on aviation!), won our thanks with his authoritative 2005 text The Advanced Projection Manual. Now the International Federation of Film Archives, which co-sponsored the earlier volume, has brought out his new FIAF Digital Projection Guide.

It’s a comprehensive overview, written with great lucidity and packed with charts and specs. Sætervadet covers the Digital Cinema Package file system, projection systems, 3-D systems, sound formats, and best practices for projectionists, including advice on preparing one’s own DCP hard drive. Along with judicious presentation of rival formats, Sætervadet provides informed opinions, including a persuasive account of why 4K projection is much to be preferred to 2K. As an inveterate sitter in the Raccoon Lodge, I was happy to learn of the importance of the “front-row rule” in measuring resolution in relation to screen size.

This is an indispensable book for anyone interested in current cinema technology. I wish it had been available when I wrote Pandora’s Digital Box. The Guide is available direct from FIAF and from Amazon.uk.

Finally, from the enterprising Potemkin Press comes a new edition of Eisenstein’s writings on Disney animation. An inveterate cartoonist himself, usually somewhere between Cocteau and Keith Haring, the polymath director reflected on Uncle Walt the artist throughout his career, but most deeply while he was at work on Ivan the Terrible. SME made no bones about it:

The work of this master is the greatest contribution of the American people to art–the greatest contribution of the Americans to world culture.

As often happens, Disney furnishes Eisenstein the occasion to launch a fantasia on what he’s been reading and thinking about since the last time he wrote. He hits on the ceaseless, “amoeba-like” change that animation permits and that Disney cartoons exploit. SME’s ruminations lead him into myth, ritual, medieval art, the drawings of Thurber and Steinberg, and much more. Typical is this:

TUSHMAKER’S TOOTHPULLER by John Phoenix, of course, stands in line with other plasmatic fancies. (Never observed this before.) Now I’ve just read some verses on the same topic by Walter de la Mare….

Much of the material is irreducibly private and may never be fully understood. Feel free to unleash your own associations on passages like this:

Octopi: Most plasmatic.

Merbabies.

The tiger is a goldfish.

↓

Lawrence.

↓

Horses like butterflies.

St. Mawr like a fish.

Back in 1986, Jay Leyda and Alan Upchurch gave us Eisenstein on Disney, a fine selection from these energetic, perplexing jottings. Unfortunately that book is currently rare and expensive. Now we have Sergei Eisenstein: Disney, edited by Oksana Bulgakowa and Dietmar Hochmuth. Based on recent archival discoveries, it incorporates more pieces and includes a more extensive commentary and an index. Dustin Condren’s translation reads fluently, and there are many illustrations. The editors employ varying fonts to label passages in different languages, although all passages, including SME’s obsessive cut-and-pastes from books, are fully rendered in English.

Oksana’s Afterword provides a historical account of the manuscript and an in-depth guide to the development of SME’s ideas at the period. She’s particularly helpful in explaining Eisenstein’s flirtation with psychoanalytical ideas. She flavors her account by itemizing the archaeological artifacts the researcher encounters:

Eisenstein writes on an incredible variety of paper–on the back of his own manuscripts and others’ screenplays, on Mosfilm’s or the film committee’s stationery, on concert programs. The annotations from the year 1944 are scribbled on 1942 calendar sheets. Call numbers for books from the library, telephone numbers, doctors’ prescribed diets, and a grocery list are all found in the text–cream meringues, sultanas, nuts.

When I learn things like this, I like him even more.

Sergei Eisenstein: Disney is a remarkable addition to the Eisenstein literature and ought to provoke lively debate in the animation community as well. But try to find or photocopy the Leyda/Upchurch volume too. It includes SME’s earlier 1932 notes on his drawings, where he floats his ideas about “plasmation,” and it has some different illustrations and its own helpful commentary. Both collections are invaluable to every Eisensteinian, which in a just and righteous world should mean everybody.

P.S. 28 January 2013: Thanks to Manfred Polak for correcting a misspelled name.

Thanks also to Peter Parshall for corrections in my memory of his visit (Compaq, not Apple as I’d said; Lilly grant; 1988; all duly adjusted above.) Details, details. He adds:

You probably don’t remember but the other students complained to you after the first day’s class because of the noise my computer keys made as I clattered away, trying desperately to keep up with the barrage of information coming at me. So when I came up to speak to you in my turn, you suggested that perhaps I shouldn’t use the computer. I was stunned! (All that money! That was one of the very first laptop models manufactured and it had cost a bundle!) The next day, instead of sitting in the back, I sat in the front row so that your voice would drown out my clatter and I announced at the class break that I’d put my notes on reserve. The complaints suddenly stopped.

Then on the first day of spring term, I was startled when a student rushed up to me and asked very anxiously what had happened to my notes!!! (I had taken them off reserve after exams were over, thinking they would no longer be needed.) No, No, he exclaimed. All the students wanted copies for prelims. So I put them back on reserve.

The climax to the joke came three or four years later when I flew into Rochester, NY, for a film conference and taxi-pooled with several other conferees to the hotel. I was delighted to learn that they were all grad students from UW, although I didn’t know any of them. I didn’t mention my name, it being of no scholarly importance, but simply said I taught in Indiana and had spent a sabbatical year at UW. A female voice with a rich British accent popped up from the back seat: “Oh, you’re Peetah Paahshall.” Turns out she had acquired a set of the samizdat. I chuckled at the thought of them still being handed on, from one generation of students to the next. . . . I know I learned a ton that year in Madison and if I could help the learning process for some UW students in return for all your hospitality, I was happy to do so.

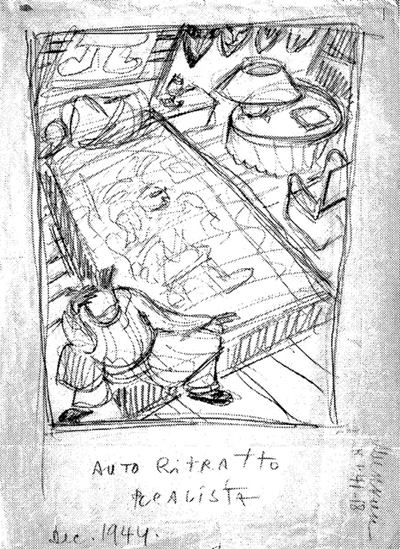

Eisenstein, Self-Portrait (1944).