Archive for March 2013

The 1940s, mon amour

The Dark Mirror (1944).

DB here:

With the indispensable assistance of our web tsarina Meg Hamel, I’ve just put up an essay on Hollywood film of the 1940s. It’s called “Murder Culture: Adventures in 1940s Suspense.” It’s long, I warn you. But if you’re interested in American film history, thrillers, Alfred Hitchcock, or all of the above, you could find it worth checking out.

Now for a flashback. Cue track-in, soft dissolve, ominous music.

I was born in 1947, so the Hollywood cinema of that day really belonged to my parents’ generation. Yet why do I feel that the 1940s-early 1950s cinema is “my Hollywood” in a way that the 1960s and 1970s aren’t?

I was born in 1947, so the Hollywood cinema of that day really belonged to my parents’ generation. Yet why do I feel that the 1940s-early 1950s cinema is “my Hollywood” in a way that the 1960s and 1970s aren’t?

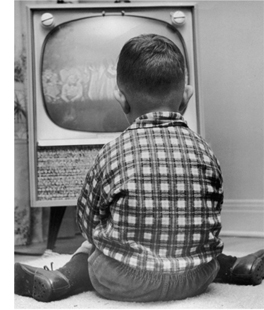

TV is a big part of the answer. Living on a farm, I saw far more movies on TV than in theatres. That’s why I don’t have as absolute a fetishism for 35mm as my baby-boom peers who grew up in cities. They could amble down to the local Bijou every day after school and soak up current movies and classics. I couldn’t, so I can sympathize with kids today who see most of their movies on monitors. That’s what I did, and—truth be told—what many urban cinephiles did too.

What I could see, thanks to Rochester and Syracuse television stations, were those films that had sold in packages of 16mm prints. Fattened out by with commercials, sometimes trimmed to fit schedules, old movies were treated as filler. And while some of the 1930s movies, chiefly the Bs featuring Mr. Moto and Charlie Chan, became lifelong favorites, it was mostly the 1940s and early 1950s films that stuck with me.

There were Citizen Kane and Magnificent Ambersons, of course, which movie books steered me toward. But there was also Ball of Fire, For Whom the Bell Tolls (in black and white), and Suspicion. Those I remember most vividly, but today, watching some obscure 40s item, I find dim memories of that sometimes flaring up too.

From college through graduate school, I made 1940s Hollywood a touchstone. My first published essay, back in 1969, was on Notorious. As a film collector, I favored 1940s things, from His Girl Friday and Fallen Angel to Ministry of Fear (below) and The Shop around the Corner. When I started teaching at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, the Wisconsin Center for Film and Theater Research enabled me catch up on Warners, RKO, and even the stray Monogram. In my courses we showed prizes like Meet Me in St. Louis and The Locket. I was happy when several of my students, such as Diane Waldman, Brian Rose, and Fina Bathrick, took up 1940s topics for their research.

The era pulled in my research too. In Narration in the Fiction Film my preferences were exposed; some friends noticed that most of my prime American examples (The Big Sleep, In This Our Life, Murder My Sweet, The Killers, Secret beyond the Door, Shadow of a Doubt, Rear Window, etc.) came from the 1940s and early 1950s. The conversation sort of went like this. Q: So I guess for you, David, every narrative is a mystery? A: Yes.

In The Classical Hollywood Cinema I could justify my 40s emphasis because that era saw significant changes in storytelling. I couldn’t avoid all those flashbacks, all that deep focus, all that noir and melodrama. Still, as my examples of ordinary Hollywood sound picture I picked Play Girl (1940) and The Black Hand (1949). Likewise, when I wrote an article about how we’re led to forget key story information, I fastened on Mildred Pierce. And one theme of The Way Hollywood Tells It, a book purportedly about contemporary moviemaking, is the debt that the Movie Brats and their successors owe to the 1940s.

No surprise, then, that when I was asked in 2011 to prepare some lectures for Belgium’s summer film college, I decided to revisit 1940s Hollywood. I began preparing in the spring, and had plenty of time to watch films while I was hospitalized with pneumonia. The more I watched, the more I came to believe that we still don’t know this period in its full artistic richness–and peculiarities.

True, we have plenty of studies that see all sorts of 40s films as reflections of the war or postwar malaise. Certainly, as well, the literature on film noir and the female Gothic will continue to grow. (Indeed, these categories weren’t available to people of the time; they just called those movies “melodramas.”) But I wanted to explore broader trends in cinematic storytelling that were pioneered or consolidated after 1940 or so. That meant looking at family sagas like How Green Was My Valley (see Kristin’s post here), as well as dramas like Daisy Kenyon and All About Eve and other things that caught my interest.

During a July week in Antwerp, I delivered the lectures. It was exhilarating to re-see the films in 35 and discuss them with a lively bunch of participants. But my ideas kept developing. I couldn’t shake the films and the spell they cast on me. Over two years I’ve continued to watch and read and turn ideas over.

End of flashback. Cue soft dissolve, track out, music with warmer harmonies.

I’m now writing a book, one that’s relatively short (honest!) and that, I hope, creates an original perspective on American film of the 1940s. Although the new piece centers on the suspense thriller, the book will look at other genres too. You can get the flavor of the project from these entries on the 1940s and early 1950s:

“Intensified continuity revisited.” The Shop around the Corner vs. You’ve Got Mail.

“Creating a classic, with a little help from your pirate friends.” How His Girl Friday acquired its stature today.

“Foreground, background, playground.” This is a trailer for “William Cameron Menzies: One Forceful, Impressive Idea.”

“Chinese Boxes, Russian dolls, and Hollywood movies.” On embedded flashbacks.

“Julie, Julia, and the house that talked.” On narrational strategies and wild time schemes.

“Puppetry and ventriloquism.” Bits and pieces from the 2011 lectures, focusing on anti-realism and competition among directors.

“Despoiling the movies.” On 1940s attendance habits.

“Pike’s peek.” Imaginary product placement.

“Play it again, Joan.” Analyzes the technique of replaying scenes seen or heard earlier.

“Bette Davis eyelids.” Joan’s rival and her performance tactics.

“Hand jive.” General piece on performance and gesture, with discussion of All the King’s Men.

“I Love a Mystery: Extra-credit reading.” A sort of dry run for the web essay.

“Alignment, Allegiance, and Murder.” How Lang attaches us to characters in House by the River.

“DIAL M FOR MURDER: Hitchcock frets not at his narrow room.” Touches on Dial M‘s debt to 1940s experiments.

“A dose of DOS: Trade secrets from Selznick.” On Selznick’s films, including those directed by Hitchcock.

“SIDE EFFECTS and SAFE HAVEN: Out of the past.” On current thrillers’ debt to the 1940s; ties to today’s web essay.

Most of these and much of the new “Murder Culture” essay probably won’t surface in the final book. I wrote the pieces in order to clarify some research questions and to sketch out some answers. If you have any suggestions or corrections, feel free to correspond.

Meet Me in St. Louis (1944).

SIDE EFFECTS and SAFE HAVEN: Out of the past

Safe Haven; Side Effects.

DB here:

Occasionally someone will ask me how I watch a movie. Here’s a stab at an answer. If the film presents a story, fictional or nonfictional, I try to get engaged by it, as most viewers do. I also try to watch for how the filmmaker shapes sounds and images. Such things are hard to analyze on the fly, but we can at least be shot-conscious. I suppose as well there’s a small part of me asking whether what I’m watching is good or bad. Another part takes notice of what many viewers spot today: the sorts of story roles allotted to women and members of minorities.

At the same time, one module in my head seems to be looking for historical precedents and parallels to what I’m seeing. The purpose isn’t to dismiss current movies with “Aw, this has been done long ago.” Instead, I think I’m looking for ways in which earlier forms and styles are accepted, recast, or rejected by the creative choices being made today.

For instance, as I was watching Safe Haven and Side Effects, I was thinking of the 1940s.

Not that other periods haven’t left their traces. Both movies depend on crosscutting, something that goes back to the 1910s, as does the goal-oriented protagonist. Both rely as well on analytical editing, with Soderbergh in his usual spare way minimizing establishing shots in favor of compact constructive editing. The wobbly handheld shots cropping up in both films hark back to the 1960s and filmmakers’ periodic revival of them. Four-part structure: check. Rule of three: check. And so on.

But what popped out at me was something that I’ve noticed before. Films of the last twenty years or so borrow a lot of storytelling strategies that originated in the 1940s and carried through into the early 1950s.

In The Way Hollywood Tells It, I argued that 1990s Hollywood drew upon this heritage and in some ways pushed it farther. It isn’t just neo-noirs like Reservoir Dogs and Memento that owe a debt to the earlier period. Lots of films in many genres now casually use flashbacks, voice-overs, restricted points of view, multiple protagonists, network narratives, and replays of scenes from different perspectives—all strategies pioneered or consolidated in the 1940s. These techniques have become so accepted a part of mainstream moviemaking that we may forget that a comedy like The Hangover or a prestige drama like The Iron Lady presents fairly elaborate time schemes or tricks of character subjectivity.

We also tend to ignore the sheer eccentricity of the period. The 1940s introduced movies letting a house tell the story or embedding flashbacks within flashbacks within flashbacks. Characters dreamed things that came true, or realized that they were actually dead. Sometimes dead people narrated the story. All in all, things got pretty strange.

Part of that era’s legacy is the suspense thriller as we know it. I’ll be putting up a web essay on the development of the genre soon, but for now consider these two recent releases as heirs of that tradition. Of course there are big spoilers ahead.

Spooked

Like many 1940s thrillers, Safe Haven centers on a woman in peril. Most often the heroine is trapped in a house, and an unseen force or a ruthless husband is trying to kill or incapacitate her. The prototype is Gaslight (1944), where as often happens, the wife is rescued by a “helper male,” a romantic alternative to the husband. Variants of this plot include The Spiral Staircase (1946) and The Two Mrs. Carrolls (1947). This sort of domestic thriller, sometimes called a Gothic, tends to fill household spaces and everyday routines with vague threats.

Instead of confining its protagonist, Safe Haven builds its plot around a woman who has left home behind. Fleeing an abusive marriage, Erin arrives in a North Carolina town and slowly enters a love affair with Alex, a widower who runs a convenience store. Meanwhile her husband Kevin tries to track her down. The fairly conventional budding romance, as Erin joins Alex and his kids in forming a new family, is threatened by the prospect of Kevin finding her and dragging her back home. As a policeman, Kevin has unusual forces at his disposal: a crucial turning point is his putting out an unauthorized wanted poster. Not only does this endanger Erin’s new identity, but when Alex sees the poster, he breaks off their affair.

On-the-run plots are usually the province of male-centered thrillers like The 39 Steps and North by Northwest. It isn’t unknown, though, to make the woman a moving target. One of my favorites is Double Jeopardy (1999), in which Ashley Judd plays a wife convicted of her husband’s murder. When she learns that he faked his death, she realizes that she can’t be tried again for killing him. Released on parole, she pursues him, while her tenacious parole officer pursues her. An older example is Woman in Hiding (1949), in which Ida Lupino plays a wife who is supposedly murdered by her husband. Actually, she eludes death and tries to flee him, but he, discovering she’s still alive, catches up with her on a hotel staircase.

In such thrillers, there are two common ways you can generate suspense. Both depend on range of knowledge, as Alfred Hitchcock pointed out in 1947.

The author may let both reader and character share the knowledge of the nature of the dangers which threaten. . . . Sometimes, however, the reader alone may realize that peril is in the offing, and watch the characters moving to meet it in blissful ignorance and disquieting unconcern.

That is, the narration can attach us to a character and limit our knowledge to what she knows. Examples of this are Hitchcock’s Rebecca (1940) and Suspicion (1941), which quite strictly confine us to the heroine’s range of knowledge.

Safe Haven, like Woman in Hiding, takes the alternative option: omniscience, or what Hitchcock calls “sharing the knowledge of the dangers.” Crosscut scenes show Erin in Southport while Kevin follows her trail. Other crosscut scenes introduce us to Alex’s problems of raising his kids and grieving for his wife.

As Erin gradually settles into the community, we know that Kevin is closing in. He arrives during a town celebration, and the crosscutting becomes tighter. Thanks to Kevin, the store catches fire and endangers Alex’s daughter, while Kevin drunkenly wrestles with Erin at gunpoint.

Suspense and mystery go hand in hand, and suspense films have a habit of suppressing information about past events. Woman in Hiding begins with the wife’s car plunging into the river; later we get a flashback explaining what led up to the accident. Safe Haven begins with a black-haired woman hysterically running out of a house and taking refuge with a neighbor. What has led to this? The woman, now a blonde, then boards a bus, while we see a man with police credentials questioning witnesses and stopping other buses.

The plot is organized so that we don’t know for quite some time why Erin is being pursued by this exceptionally zealous detective. And some fragmentary flashbacks, mostly in the form of dreams (a favorite 40s device), hint that she has killed a man. Gradually, however, there are hints that this cop isn’t what he seems. Not until the end of the third part (circa 80:00) do we learn from a full flashback that the cop is her husband. Kevin is a crazed alcoholic who began to strangle Erin one evening; she stabbed him and fled her home. The teasing flashbacks, along with the suggestion that Kevin’s pursuit is an official inquiry rather than a private vendetta, misled us. What we saw at the start was Erin escaping from an abusive marriage.

A lower-key form of delayed and distributed exposition involves Alex and his kids. Instead of filling us in immediately on Alex’s life with his wife, we learn of their married life gradually. After Alex has fallen in love with Erin, he retreats to a room kept in memory of his dead wife. He riffles through letters she left behind, to be given to Josh and Lexie when they grow up. Later, Alex abandons Erin because of the wanted poster, and he retreats to his wife’s room, where he has a change of heart and goes to bring her into the home.

Why the change of heart? An unusual aspect of Safe House is the injection of, ah, otherworldly intervention. While living in her cabin, Erin meets a neighbor, Jo, who encourages her to get to know Alex. In the epilogue, Alex gives Erin one of the letters from his wife’s desk, labeled simply, “To Her.” It’s a sympathetic message expressing the wife’s support for the next woman to be wife and mother to her family. The picture inside is of Jo. Earlier, in the sacred space of Jo’s room, Alex seems to grasp that he has to reunite with Erin. At the climax, Erin, dreams that Jo is warning her that Kevin has caught up with her. As angel, ghost, or spirit—you choose—Jo has brought everyone together.

Reviewers, in this cynical age, scoffed at this device. I didn’t mind it because I liked its tie to tradition. Ghosts and angels have haunted American cinema from the start, but in the 1940s they played very prominent roles—not just in comedies like Topper Returns (1941) but in dramas. Beyond Tomorrow (1940), Our Town (1940), Happy Land (1943), A Guy Named Joe (1943), The Uninvited (1944), It’s a Wonderful Life (1947), and many other films unashamedly introduced supernatural beings as moral guides to the living. True, those films build their spooks into the premises of the plot early on, while Safe Haven saves its for a Big Reveal. But after The Sixth Sense (1999), this sort of twist shouldn’t seem too upsetting. (A second viewing reveals that Jo is unnaturally disturbed when it looks like Erin won’t bond with the family, and a few lines of dialogue take on new meanings when you know that Jo is dead.) Perhaps the gimmick seems wimpier when it’s invoked in a romantic thriller than in a masculine investigation plot.

Recommended dosage

Steven Soderbergh is one of our most exploratory directors, a filmmaker who tries different things without making a big deal about it. He’s also a cinephile who, like Cameron Crowe, admires and quietly adapts classic studio traditions. He turns out lots of movies, a habit reminiscent of the contract director of yore.

I was skeptical of his pastiche The Good German (2006), but I do admire his compact, unfussy direction, as I mentioned here. I’m a big fan of Out of Sight (1998), and I think his last batch of films, from Contagion (2011) through Haywire (2012) and Magic Mike (2012), shows him to be a director whose every project is solid and intriguing. It’s a pity he’s announced his retirement after the upcoming Liberace project.

I doubt that in Safe Haven Lasse Hallström was consciously channeling 1940s suspense thrillers, but it seems likely that Soderbergh was trying his hand at something deliberately Hitchcockian. (Reviewers needed no nudging to make the comparison.) Beyond comparisons with the Master of Suspense, Side Effects’s debt extends to two plot patterns of the 1940-early 1950s that Scott Z. Burns’s script ingeniously combines.

The first is what I call the Crazy Lady plot. The Snake Pit (1948) is probably the clearest example, but there are many others, including Bewitched (1945), Dark Mirror (1946), The Locket (1946), Shock (1946), Possessed (1947), and Whirlpool (1950). The plot pattern can be found in literary thrillers too, such as Margaret Millar’s The Iron Gates (1945) and John Franklin Bardin’s fine Devil Take the Blue-Tail Fly (1948). Hitchcock didn’t tackle a Crazy Lady plot until Marnie (1964), but in the 1940s he tried a Crazy Gentleman variation in Spellbound (1945).

In such films, the woman is the mystery. What is wrong with her? Why do her problems have such horrible consequences for her and others? Often the woman displays an abnormal division in her mind: the prospect of a split personality is never far off. The key factor is that her behavior is inconsistent. A rich woman shoplifts (Whirlpool), a sweet girl fatally stabs her fiancé (Bewitched). Accordingly, only a psychoanalyst can probe the sick woman’s behavior and track down the founding trauma, typically something that happened in childhood. A crucial convention is the scene in which the woman breaks through and realizes what ails her, as in this moment from Whirlpool. It’s typical of this plot that therapeutic dialogue is often paralleled by police questioning.

Side Effects gives the Crazy Lady’s mental problems a modern spin. Emily is suffering from depression, and her husband Martin’s recent release from prison hasn’t helped her recover. After ramming her car into a parking-garage wall, she’s cared for by Jonathan, a hospital psychiatrist also in private practice. He starts her on antidepressants, eventually giving her one recommended by Emily’s previous psychiatrist, Victoria. This seems to help, although it induces Emily to sleepwalk. While she’s apparently sleepwalking, she stabs Martin to death.

Now Jonathan is in a bind. If the drug Ablixa has been misprescribed, Jonathan is responsible for Martin’s death and Emily’s fate. Jonathan defends Emily and his testimony helps win a verdict of not guilty by reason of insanity. He continues to supervise her recovery while his career collapses. His patients abandon him, his partners cast him out of their business, and he’s dropped from a lucrative experiment. He’s also being investigated by his professional association.

In other words, Jonathan is now fulfilling a second 1940s plot pattern: The innocent man trapped by circumstance. He might be a murder suspect (Stranger on the Third Floor, 1940; Phantom Lady, 1944; The Big Clock, 1948) or an ordinary guy dropped into international intrigue (Journey into Fear, 1943; The Ministry of Fear, 1944). Side Effects combines this noirish convention with the Crazy Lady plot. It turns out that Emily and Victoria have conspired to set up Martin’s death. Emily actually hates her husband, and she’s learned enough from his insider-trading schemes to understand that a scandal could drive down Ablixa’s stock price. She and Victoria, who have become lovers, can make millions as a result of the murder.

Yet suspecting all this doesn’t help Jonathan. Emily can’t be tried again, and as Jonathan begins to grasp their scheme, Victoria draws the net tighter around him. She sends his wife faked photos suggesting that he and Emily have had an affair.

In 1947, novelist Mitchell Wilson pointed out an important convention of the thriller. He claimed that the defining feature of the genre was a fear felt by the protagonist that is communicated to the reader: the protagonist is in continual danger. But when the threat reaches its peak, the worm must turn.

The framework of the suspense story is the continual struggle of the frightened protagonist to fight back and save himself in spite of his pervading anxiety, and in this respect he is truly heroic. The action of the story does not consist in mere activity, but in the hero’s change of mood in response to changing circumstances.

Jonathan’s desperation leads him to concoct a scam of his own. Since Emily is in prison and can’t communicate with Victoria, he is able to play them off against one another. Holding a physician’s control over Emily, he can convince her to double-cross Victoria and unmask her. Then he double-crosses Emily and consigns her to the asylum while returning to his family.

Again, I’ve ironed out the ups and downs of the film in order to lay out the plot’s design. In the actual telling, we’re attached first to Emily and then more closely to Jonathan. The overall pattern resembles that of Whirlpool, which concentrates first on the way the wife’s kleptomania draws her to the sinister therapist Korvo, and then shifts to the investigation undertaken by the police and her husband, a psychoanalyst. (Whirlpool, like Side Effects, centers on dueling shrinks.)

Here the Crazy Lady premise is a masquerade, and Soderbergh “plays fair” with us about it. The 1940s films rely on mental subjectivity—voice-over inner monologues, exaggerated sound effects, hallucinations, dream imagery—in order to show that the protagonist is truly wacko. Side Effects presents Emily objectively, relying on somber color schemes, top lighting, and Rooney Mara’s morose demeanor to suggest a young woman struggling against depression.

From the outside we watch Emily’s glum visits to Martin in prison, their frustrated sex when he gets out, her impassive crashing of her car, her confiding in her boss, and her breakdown at a cocktail party. There are a few optical POV shots, but those are justified as Emily’s numb stare–although Soderbergh does sneak past us a POV shot that, because of distorting glass, might seem to be projecting Emily’s state of mind expressionistically. (See above.) Virtually everything we see suggests a woman losing control, so that when Emily perks up after going on Ablixa, we, like Jonathan and Martin, think she’s recovering.

Safe Haven leads us to jump to a conclusion—that the cop pursuing Erin is doing so legitimately—only to rescind that by filling out the teasing fragmentary flashbacks. Side Effects does something similar, but through simple ellipsis. The plot lets us think that Emily is genuinely depressed by skipping over things it could have shown, such as her fake vomiting or her dumping the prescription pills down the toilet. Only at the climax, when Jonathan wrings the truth from Emily, do we get subjective imagery. There are artificially sun-sprayed flashbacks of her days with Martin just before his arrest, as well as glimpses of her therapy with Victoria, followed by replays of the suicide attempts, now revealed as faked.

The 1940s popularized this sort of filling-in flashback, in which a replay shows items that were left out of an earlier presentation. The most famous example is the return to the opening of Mildred Pierce (1945). Now as then, we can’t completely trust a thriller’s narration. There are mysteries in the story, but there are also mysteries in the storytelling. No matter how much a thriller seems to tell us, key information is usually held back, and the suppression won’t always be signaled. To get Rumsfeldian: there are always known unknowns, but thrillers trade in unknown unknowns, data we didn’t realize were there.

There’s a lot more to say about these movies. For example, both trade on a premise common to the 1940s and American movies thereafter. Call it the Margaritaville Rule: There’s a woman to blame. Erin brings calamity to Southport and trauma to her would-be family, and Jonathan’s travails are the result of two scheming women, seconded by a hard-edged wife who won’t hear out his explanations.

Moreover, I hope it’s clear that I don’t think these two recent releases are merely cloning 1940s conventions. They incorporate subjects and themes of our time, like spousal abuse and the insidious power of Big Pharma. They exhibit some innovative plotting, such as the revelation of a guiding spirit in Safe Haven and the combination of Crazy Lady premises with the Cornered Innocent in Side Effects. And Soderbergh’s offers an exercise in crisp direction, from its conventional opening shot to its grimly symmetrical closing one.

My point is simple: However new our films may seem, whether they’re accomplished (Side Effects) or banal (Safe Haven), in important respects they’re continuing traditions that go back decades.

Why then, you may ask, do so many academics and journalists insist that classical cinematic storytelling is dead? Why do they so resolutely ignore the evidence of continuity between today’s films and those that went before? That’s a mystery I can’t solve.

Hitchcock’s remark about the range of knowledge and suspense comes from “Introduction: The Quality of Suspense,” Alfred Hitchcock’s Fireside Book of Suspense (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1947), viii. Mitchell Wilson’s remarks on fighting back are in “The Suspense Story,” The Writer 60, 1(January 1947), 16. His novel None So Blind (1945) became the Renoir film Woman on the Beach (1947).

The idea of the “helper male” in the Gothic is developed by Diane Waldman in “’At last I can tell it to someone!’: Feminine Point of View and Subjectivity in the Gothic Romance Film of the 1940s,” Cinema Journal 23,2 (Winter 1984), 29-40.

For more background on the 1940s thriller, see the web essay, “Murder Culture: Adventures in 1940s Suspense” and this blog entry. Another blog entry discusses replays in 1940s and 1950s American film. For more arguments about the debts of today’s films to studio Hollywood, see The Way Hollywood Tells It and other entries on this site. I analyze the duplicitous opening of Mildred Pierce, along with its revelatory replay, in this entry and its accompanying video.

Today’s entry neglects another important component of Side Effects: the music. For that, see Roger Ebert’s acute review. Expressive scores are, needless to say, central to 40s thrillers too.

Mike Grost’s encyclopedic website supplies a great deal of information about the mystery genre.

Side Effects.

P. S. 24 March 2013: Thanks to Gabe Klinger for correcting a dumb date mistake!

I’ll never tell: JASON reborn

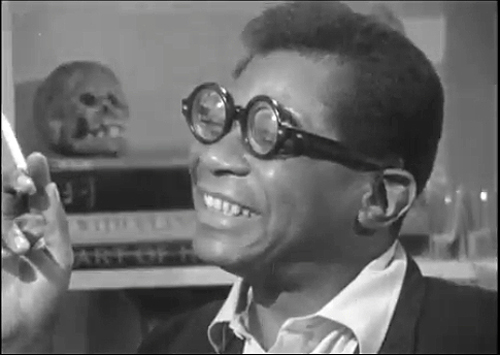

Portrait of Jason (1967).

DB here:

A white-walled apartment; no windows visible. Screen left: a day bed wedged into the corner. Center of screen: A fireplace and mantelpiece. Screen right: an easy chair with an end table boasting a lamp and ashtray. Behind it a bookcase. It’s as colorless a performance space as you could ask for, except perhaps for the skull on a bookshelf; but even that isn’t real.

In this arena a slender black man with thick Harold Lloyd glasses and a winning smile talks to us. His first words, delivered with calm sincerity, are immediately revealed as false.

My name is Jason Holliday. My name is Jason Holliday. (Breaks into laughter.)

(With a confiding smile) My name is Aaron Payne.

Over a single night, from 9 PM to 9 AM he talks to the camera, and eventually with the unseen filmmakers. High on marijuana and drunk on single malt scotch, he recounts his life as a gay hustler, recalls his family and childhood, and offers his analysis of how to behave around whites. He strikes attitudes, mimics the slaves in Gone with the Wind, and sings show tunes.

At first the filmmakers encourage him to tell this or that story, but late in the film one offscreen voice presses him. “Why’d you write letters about me?” “You should suffer.” “You’re full of shit.” Near the end Jason is sobbing. “If you don’t know,” he says, “I love you.” The offscreen voice is pitiless: “Stop that acting.”

Portrait of Jason (1967) is a legendary film that until recently had gone astray. Last Friday our Cinematheque hosted the US premiere of the restored version. The movie tells quite a story, but so too does Dennis Doros, VP of Milestone Films and the man whose tenacity brought back this delightful, disturbing record of Jason’s long night.

In and out of focus

It was a shocker in its day. What other film talked so frankly about gay life, race relations, and drug use? Where else would you hear virtually every four-letter word in the American vernacular? Shown in festivals and independent art houses, it won an astonishing level of praise. Here is Newsweek:

Jason lives, and Jason gives one of the most incredible performances ever recorded on film. This inverted Everyman, this anti-matter Jack Armstrong has a terrible tale to tell about how much it can hurt to be human, and he tells it in magnificently rich language with the gay desperation of an artist.

But the film was doubtless worrying. It circulated in the same year as Blow-Up, Bonnie and Clyde, The Graduate, Bike Boy, In Cold Blood, I am Curious (Yellow), Rush to Judgment, and I, a Woman—a year in which studio films, exploitation, art movies, and the underground seemed to be joyously blitzkrieging conventional values and good taste. Portrait of Jason opened at the New York Film Festival after a summer in which American cities had been shaken by riots in black neighborhoods. Now came a film in which a black man blithely reveals the cynicism behind his shuck-and-jive for rich white employers. And he’s a gay prostitute.

The director, Shirley Clarke, was a member of the New American Cinema group around the Film-Makers Coop and the magazine Film Culture, but she never fitted into any clear-cut category. She made dance films and some lyrical shorts like the zesty Bridges Go Round (1958), but she never joined the avant-garde tradition typified by Stan Brakhage, Michael Snow, and Ernie Gehr.

The director, Shirley Clarke, was a member of the New American Cinema group around the Film-Makers Coop and the magazine Film Culture, but she never fitted into any clear-cut category. She made dance films and some lyrical shorts like the zesty Bridges Go Round (1958), but she never joined the avant-garde tradition typified by Stan Brakhage, Michael Snow, and Ernie Gehr.

Her other feature-length films (The Cool World, The Connection) owed something to American cinéma vérité. Variety sourly remarked of Jason, “C’est la vérité,” and ran its review alongside a review of Frederick Wiseman’s Titicut Follies. But Clarke’s daughter Wendy recalls that although Shirley was friends with vérité filmmakers, she doubted that they could capture reality objectively. Leacock and Pennebaker would have found it impure to jab their own comments into the subject’s monologue the way Clarke and her lover Carl Lee do. Clarke’s approach is closer to that of the French cinéma direct, as pioneered by Jean Rouch and Chris Marker. In Le joli mai (1963) the filmmakers ask their interviewees frankly: “Are you happy?” This question underlies Portrait of Jason too.

Apart from the coaxing and goading interjections, Clarke’s filming method seems artless. There are fewer than fifty shots in 105 minutes, and they’re linked by black frames and out-of-focus passages. Both transitions mimic casual shooting. Yet Dennis Doros and Wendy Clarke pointed out that Clarke loved cutting. She was aware of the paradox:

I had enormous patience in terms of editing and I’ve always adored that part of making films, and in an odd way as I develop as a director I set up less and less situations to edit. The better I’ve become as a director, the less editing, the more I’m thinking in terms of the last twenty or thirty minutes that will have no editing at all.

In Jason the cutting isn’t as casual as it might seem. The blurry passages conceal edits, and the order of scenes doesn’t reflect the progress of the shoot. It will take patient research to determine the original chronological order of the reels we see. Clarke claimed that she enjoyed editing because at that phase she was really discovering her film.

Clarke’s apparently loose shooting, often running the camera until the magazine is empty, may seem a version of Warhol’s static films like Eat. It seems likely that she also learned from Warhol’s approach to performance. His psychodrama-based dramaturgy, as explained in J. J. Murphy’s fine book, constantly hovers between confession and put-on, and this is central to what happens in Clarke’s film. But Clarke gives her movie a more clear-cut narrative contour than Warhol would, with Jason’s monologue devolving from grinning self-assurance to stricken self-exposure.

Clarke and her crew acknowledge the act of filming, although they don’t emerge from behind the camera, as some do in The Connection. This recognition of artifice can encourage the subject to perform, to play up to the camera for the approval of the filmmakers and the audience. And a chance to perform is exactly what Jason wants. Now, he chortles, he can show off the nightclub act he’s been working on. The film is at once an audition and an effort to define himself. He’ll create “a picture I can save forever—one beautiful something that’s my own.”

So in the stage space between the day bed and the armchair, he strolls and poses. He fires off randy one-liners like “If I’d been a ranch, I’d be called Bar None.” Flipping his boa, he channels Mae West, Butterfly McQueen, Dorothy Dandridge, and Harry Belafonte. (Did he rename himself in honor of Judy Holliday?) He jiggles ice cubes in his glass with the winking panache of Dean Martin at the Sands. Clarke once said that in watching the rushes she was reminded of her choreography films: Jason seemed to be dancing.

To recover from his numbers, Jason flings himself offstage, flopping back on the daybed or sinking into the armchair as his cigarette burns down to the filter. In these moments, he seems to be candid. He admits that even with all the money he’s borrowed from friends, he’s not ready to take the show-business plunge. Drunk and giggling, he tells of childhood beatings with a razor strop: you mustn’t stick your butt up high but press yourself against the bed; that hurts less. His oscillations of mood are dislocating, passing from exuberance to frankness to self-mockery. Moments of self-celebration (“I’m a male bitch”) can also seem inadvertent glimpses of vulnerability–which may be exactly what Jason wants us to think. At one level Jason gives lessons in impression management.

I see his tears at the climax as born of authentic pain, but I can’t be sure. Earlier in the film he bragged: “When I do my pathetic bag, I’m really pathetic.” The layers of Jason’s one-queen show seem endless. Clarke said in an interview that everything he does on film—his jokes, stories, even the weeping—she had seen many times before. “His entire life is a role.” He seems to spill everything, but one of his mottos, delivered with finger snaps, is: “I’ll never tell.”

Treasure hunt

Wendy Clarke, Dennis Doros, and Maxine Fleckner Ducey.

How was this extraordinary film brought to light again? That was the story Dennis Doros told at our departmental colloquium the day before the screening. His company Milestone has specialized in reviving forgotten or neglected films of all types, including American independent work like Kent MacKenzie’s The Exiles and Charles Burnett’s Killer of Sheep. Simply trying to get a quality version of Portrait of Jason took him on a hunt that revealed, after many twists, that the closest thing to an original print was residing here in Madison, Wisconsin.

Back in the 1960s and early 1970s, our Wisconsin Center for Film and Theater Research made an effort to collect off-Hollywood cinema, including the works of East Coasters like Emile de Antonio, Doris Chase, and Shirley Clarke. Clarke’s collection, like several others, harbors vast amounts of personal papers and film material.

Clarke shot Jason on 16mm, but no negative has yet been found. There were 35mm prints made, and some wound up in archives, notably at the Museum of Modern Art. But among the material Clarke began giving the Center in 1973 were six reels of silent 16mm footage and several reels of sound recording. When they were inspected, the reels were believed to be either outtakes or stretches of a rough cut. We didn’t yet have a release print of Jason to compare them to.

Many years later, after searching high and low across the world, Dennis had the good idea of adding up the footage counts of our reels. The length was four minutes longer than the final running time of the film. After further research, our footage was revealed as Clarke’s original cut of summer 1967, which was trimmed and revised for the film’s official premiere at the New York Film Festival. This was, says Dennis, “the great irony in the search. Because Shirley Clarke had created a film that was meant to look unedited—filled with out-of-focus shots and black leader—Shirley’s 16mm fine-grain master was hidden all these years as outtakes!”

Our archivist Maxine Fleckner Ducey assisted Dennis throughout his quest. They found that the sound material, alas, was indeed outtakes, and Dennis still needed a good 35mm print of the Film Festival/release version for sound and final checking. More hunting ensued. Searching through the WCFTR collection, Dennis found an old telegram from Jacques Ledoux of Belgium asking permission to borrow a print from the Swedish Film Institute. Dennis contacted Jon Wengstrom at that archive, and soon he had a copy that could guide the restoration.

The whole process was enabled by funding from the Academy and from a Kickstarter campaign. To support that effort, Dennis and his wife and business partner Amy Heller made a video that traces their search for Jason. Their restored version had its world premiere at the Berlin Film Festival, and it will go on to other festivals and selected theatres. The image and sound quality far surpasses that of earlier versions in circulation.

A sort of epilogue came when Dennis and Wendy Clarke visited Madison last week. They dipped into Shirley’s vast collection, and in only two days they found treasures of a personal as well as professional nature. Perhaps some of their discoveries will surface as bonus materials on the eventual DVD release. Dennis and Wendy stayed on to introduce Friday’s premiere and take questions.

A charming pendant to Jason was the screening of a half-hour of Wendy’s Love Tapes series. In the 1970s Shirley shifted to making videos, and Wendy followed her path and became a major video artist. The series began as Wendy’s video diaries, but in 1977 she began recording people talking about what love means to them. Each person sat alone in a room, seeing her or his image on the monitor, and talked for three minutes. Over the years, the formats shifted from reel-to-reel tape to VHS to DVD, but the theme remained the same.

Wendy now has over 2500 tapes, shot in museums, schools, shopping malls, prisons, centers for battered women, and even in a booth at the World Trade Center. Ideally, she says, everyone on the planet should make one—a goal that isn’t so far-fetched thanks to smart phones and the Internet.

The Love Tapes assembly we saw with Jason was broadcast on PBS in 1982, and it was alternately grave and exhilarating. People celebrated love they’ve found but also mourned its passing and reflected on how it shaped their lives. Wendy has tried other themes, notably death, but love works best. “You talk about everything in it.” Sort of what happens in Jason too.

Thanks to Wendy Clarke and Dennis Doros for their visit to Madison, and to Jim Healy for facilitating it. Thanks also to Joe Lindner and Mike Pogorzelski, two graduates of our program, for enabling the Academy to take part in Milestone’s project. Maxine Fleckner Ducey was a great help on the Milestone project and, on a daily basis, makes us proud to have the WCFTR connected to our program. Thanks as well to current WCFTR director Vance Kepley for background information on the Clarke collection.

Project Shirley recently won Milestone an award from the National Society of Film Critics (the company’s sixth). Look for more Project Shirley material to surface from our holdings. And who, as Dennis asked in colloquium, will write the first book on this remarkable artist?

I drew Clarke’s comments about editing from Gretchen Berg, “An Interview with Shirley Clarke,” Film Culture 44 (Spring 1967), 55; and “A Conversation—Shirley Clarke and Storm de Hirsch,” Film Culture 46 (Autumn 1967), 47. The Newsweek review of Jason appeared in the issue of 6 November 1967, and the Variety review appeared on 25 October 1967.

The trailer for the new version of Jason is here; it includes side-by-side comparison of an archived 35mm print and the restoration. Clarke’s discussion of Jason’s role-playing is captured in an episode of the TV series Cinéastes de notre temps, by Noël Burch and André S. Labarthe. You can watch it here.

On The Connection, see J. Hoberman’s lively introduction on the New York Review of Books blog. Jason is a prototype of the portrait genre of documentary, a subject covered with care in Paul Arthur’s essay, “Identity and/as Moving Image,” Line of Sight: American Avant-Garde Film since 1965 (University of Minnesota Press, 2005), 24-44.

A sample of Wendy Clarke’s Love Tapes is here.

Love Tapes (1982).

16, still super

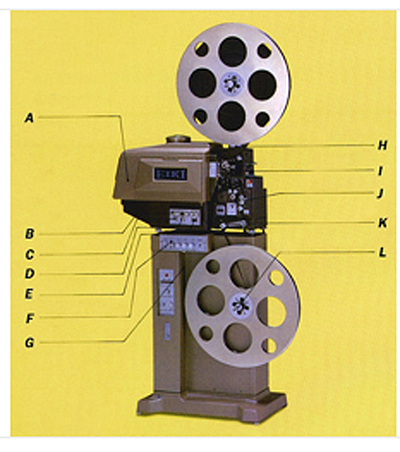

From Lost & Found Film Club.

DB back:

While I was semi-snowbound in Evanston, IL, messages kept rolling in. Many of them were responding to my account of surrendering my 16mm movies and gear. That post’s whiff of nostalgia was caught by Gary Meyer, co-director of the Telluride Film Festival.

Don’t get me started on 16mm memories. I started showing movies in 8mm at about ten years old and by thirteen I had two for changeovers on silent classics rented from Cooper Films in Chicago. For about $2 I got a full feature and short including postage. Using my parents’ record collection I could score the films. . . .

Graduated to 16mm in high school when a local church and the library each offered use of their projectors and I started collecting prints seriously. In college I got a job in the media center showing films, cleaning prints and projectors. When the department decided to buy Bell & Howell Auto-Shreds, they sold off the old projectors for $50. I knew each machine intimately and selected the quietest, gentlest RCA 400 which I still have in a booth in my basement. One of my favorite projectors.

With 16mm projectors I have shown movies on garage doors from my apartment, in a barn, an orchard or two, and most famously on clouds, which resulted in the police department getting many phone calls about aliens.

Gary reports that his former venue, the Balboa Theatre, has given its theatrical Eiki projector to the San Francisco State University film department, but it can be borrowed back if ever needed. A more acute sense of the passing of an era was reported by program curator and Czech arts consultant Irena Kovarova:

One of the sad moments in my film history was being invited to the Czech Embassy in Washington, DC to visit a room of 16mm film piles. I was asked to pick and choose which ones should be saved and which would be chucked away (the majority). It was a collection of films that the Embassy inherited from the Communist-era offices when the staff was shipped films for their entertainment (Czech popular comedies) and of course tons of “travel” and “propaganda” stuff. It was impossible to know what was really there and a lot was mediocre, but still such a sad thing that no one could really dig in and explore.

Secrets of the Incas, and non-Incas

Projection booth, Cleveland Cinematheque.

But there was good news too. In the course of that entry, I said that 16 was “nearly dead” as an exhibition format. Trust this blog’s alert readers to give a more upbeat emphasis and offer some weighty counterexamples. Don’t hesitate to use the hyperlinks!

I was confirmed in my belief that archives will keep the format going. I hear from our old friend Antti Alanen of the National Audiovisual Archive of Finland, that 16 flourishes in Helsinki.

We still keep screening 16mm regularly at Cinema Orion, and for the moment print access is still good. We recently showed three programs of Stan Brakhage movies (from Canyon Cinema) and one programme of Rose Lowder movies (from Light Cone of Paris), all in the original format of 16mm, all prints and colours perfect.

I haven’t seen Brakhage on DVD, but those who have remarked that it is not the same thing. There is something about the special sensuality of 16mm which is essential to the Stan Brakhage experience. All of those films fill up the senses.

Besides Canyon Cinema and Light Cone, LUX in London still seems to be well-stocked with good 16mm prints in commercial distribution.

Bracing news. Antti mentions as well that he used to be able to access 16mm films made for the Finnish Broadcasting Corporation, but now the agency has realized that the prints are irreplaceable and provide digibeta copies instead. The loss for showing is a gain for preservation.

I indicated as well that colleges, universities, and museums will probably maintain 16mm prints and showings. My correspondents have confirmed it, and offer some ripe local detail. Tracy Stephenson of the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, tells me that they have shown films since the 1930s and may be the only venue in Houston that still screens 16. They have a program of jazz shorts coming up in June.

Here’s John Ewing of Cleveland:

I still show 16mm on occasion (and two-projector 16mm at that) at both of my venues: the Cleveland Cinematheque and the Cleveland Museum of Art. In fact, I just ran the 16mm program from the 50th Ann arbor Film Festival tour last Thursday night at the Cinematheque. Last time I showed 16 at the art museum was in December when we screened an IB Tech print of Secret of the Incas, from the Academy Film Archive.

From the Oklahoma City Museum of Art, Brian Hearn writes:

We are pretty serious about 16mm and maintain a modest collection of about 500 prints, ranging from Lumiere Brothers shorts to studio features to avant-garde to educational films to 70s exploitation trailers. As the film medium dematerializes it makes me appreciate our collection even more, vinegar and pink fading prints included!

Calling a collection of 500 titles modest makes me grin (in envy). On the university side, Jon Vickers supplies other breathtaking information:

Indiana University Cinema programs from the University’s 16mm collection on a regular basis, with 16mm screenings at least once each month. In the IU Libraries Film Archives, there are over 80,000 items, the majority being 16mm. Within that collection is Lilly Library’s David Bradley Collection, spanning the history of cinema in the US and Europe, including classic, obscure, and some unique titles. We dedicate a series each semester to the holdings within the Bradley Collection (programmed by Film and Media Studies grad students), as well as program from the educational/non-theatrical collections and holdings.

We can’t imagine a day when we will stop screening 16mm.

With that treasure house, I can see why! Pablo Kjolseth of the University of Colorado at Boulder also defends the format resolutely. Pablo has written one of the most fiery and persuasive polemics on digital cinema. Not only does his program have an extensive library, but they are still actively collecting in 16. Moreover, as home to the annual Brakhage Center for Media Arts symposium on experimental film (coming up next week), Boulder’s campus relies constantly on 16.

Hipsters, nostalgics, and toddlers

Eiki EX-9100 Professional 16mm Sound Optical/Magnetic projector with 2000-watt lamp. Currently available on eBay for $8,500.

Perhaps the most cheering news comes from those enterprising programmers of films for public venues, both for-profit and not-. Barak Epstein of the Texas Theater uses Kodak Pageants (of my fond memory) with manual changeovers and a manual audio fader. Pittsburgh Filmmmakers, writes Gary Kaboly, uses its Kinoton and Eiki machines every couple of months. He adds:

Throwing around the idea of a “classic 16mm experimental” series in the fall. Young Hipsters see attending a 16mm show as an “event.” Old Hipsters always describe what an Art House was “back in the day.”

The Cinefamily venue of LA has established itself as home to what the local paper called “pathologically idiosyncratic programming,” and 16 adds sharp spice to the mix. Here’s Hadrian Belove, the Head Programmer, on his personal quest and the formation of the Lost & Found Film Club:

I’m definitely of an age that would be post-16mm collecting, but still got hooked. One of the great appeals of 16mm for me is it feels like the final frontier for discovering true rarities. . . . It’s kind of the ultimate format for a “digger.” Finding Christian experimental films, industrial films, student films, and copies of TV movies, episodes, and even theatrical features that simply never made it to any form of video is de rigueur.

Nothing gives me more pleasure as an explorer than trolling eBay for 16mm.

I began showing things I would buy after hours to the staff here at Cinefamily, and hadn’t even considered it as a public show. Over time, some of the “kids” on the staff started buying their own 16mm ephemera, and finally proposed taking our private show public. I thought what the hell, cost is low, and we were doing it anyway. I gave them a terrible time slot I wasn’t using (10:30 on a Wednesday).

They launched this:

https://www.facebook.com/LostFoundFilmClub

Anyway, the first show had 100 people, even at 10:30 on a Wed night. Maybe it’s those grilled cheese sandwiches!

Finally, I had noted that FOOFs (Fans of Old Films) had a noble tradition of gathering in annual conventions. Jessica Rosner, film scout extraordinaire, writes of screenings at the upcoming Syracuse Cinefest: “The majority of films will STILL be in 16mm and they will be films that are rarely available to be seen any other way.”

A further note from Pablo Kjolseth brings things back to Gary Meyer’s childhood and the FOOF in us all. Pablo hosts summer screenings in his back yard.

My Eiki Xenon projector shoots through a guest-room window to the screen in the backyard – transforming the guest room into a “projection booth” of sorts. The next [picture] is a nice ominous shot of Darth under stormy skies. . . . Although I’ve played around with some digital screenings, everyone prefers the 16mm shows. And this even though I don’t do reel-changes or employ a take-up tower – thus having small intermissions between each reel change. These intermissions are quite popular, as it allows folks time to refill their drinks, go to the bathroom, and comment on what they’ve seen so far.

As many as 60 people might show up for any screening. As the children in the neighborhood are always entranced by the projector, I try to make sure to have a couple family-friendly screenings every summer. My neighbors are great: they’ve even tolerated backyard screenings of such titles as DAWN OF THE DEAD and THE TEXAS CHAIN SAW MASSACRE – admittedly poor choices, given that in the summer heat most people sleep with their windows open and late at night they might not appreciate all the screaming and, well, chainsaws. But, so far, no complaints!

None from my end, either. Is it just me, or does Darth look more menacing here than in any other setting?

After reading these communiqués, two thoughts. First, a great many programmers are working very hard to track down and screen unusual items for their audiences. These folks and their peers are committed to exploring cinema along routes that bypass the multiplex. Who wouldn’t rather watch Secret of the Incas than, say, The Last Exorcism Part II?

My second thought comes with a pang. Was I wise to clear out my 16 collection? Our department and other collectors benefit, but still… A basement will dry out, but films that are gone are gone.

Thanks to all who wrote me, and to the Art House Convergence list serve for its stimulating conversations.