Archive for April 2013

The Maestro of Chagrin Falls

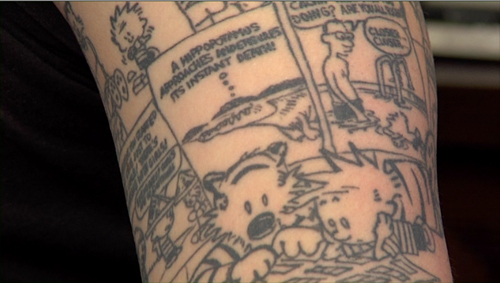

A fan’s tattoo, from Dear Mr. Watterson (2013).

DB here:

Bill Watterson, creator of Calvin and Hobbes, was probably the best cartoon draftsman since Carl Barks and Walt Kelly. His versatile line could be thick or thin, fluent or jagged. His coloring was rich, his layout experimental in the Herriman vein. His energetic picture stories provided zany humor and an unsentimental look at childhood imagination.

If Schulz treated kids as miniature adults, complete with obsessions and neuroses, Watterson saw Calvin as an adolescent in a child’s body, a rebellious teenager-to-be surrounded by adversaries and fools. Schulz’s Peanuts kids suffer in thin, wriggly lines, but Calvin’s mood swings from rage to rapture are rendered by manic exaggeration in the classic cartoon tradition. Meanwhile Hobbes, contrary to his name, exercises a gentling effect, becoming a tolerant Superego to Calvin’s Id.

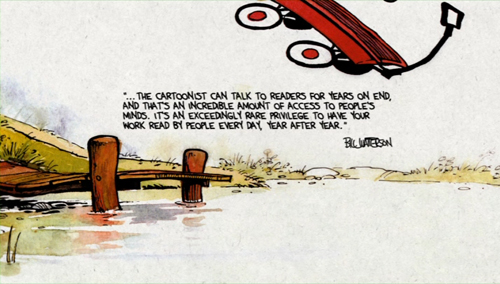

Watterson was the Pynchon of cartoondom. His studio in Chagrin Falls, Ohio yielded a solitude rare for a publishing celebrity. He almost never appeared in public and seldom answered mail. In one of his rare public gestures, he criticized syndicate power, the tired old strips put on life support, and the scramble for licensing deals. Accordingly, he permitted no merchandising beyond book collections. Any Calvin and Hobbes toys or T-shirts or decals you see around you are DIY handicraft. After ten years Watterson simply halted the strip, an abnegation that drove his millions of admirers to despair. And he has remained reclusive.

Dear Mr. Watterson, which won a Golden Badger award at our Wisconsin Film Festival, sprang from Joel Schroeder’s fondness for the strip. He realized early on that interviewing Watterson wasn’t in the cards. So he set out to find ordinary readers who would testify to their love for Watterson’s creation. He found plenty of eloquent ones, but the movie is no mere fanboy indulgence. Schroeder’s travels took him to many of today’s top cartoonists, from Berkeley Breathed to Stephan Pastis, as well as critics and syndicate executives.

By outlining the shape of Watterson’s achievement in comics history, Dear Mr. Watterson mutes its admiration with regret, and not merely because Watterson quit at the height of his popularity. The film shows that, as one interviewee puts it, Calvin and Hobbes is very likely the last great comic strip.

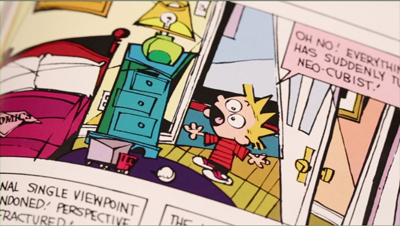

Why? The conditions of publishing have a lot to do with it. As newspapers got thinner and smaller, the space allotted to comics shrank. Complex compositions and spacious storytelling became difficult in the slots allotted to Sunday strips, while the daily panel formats were minuscule. Only the sketchiest drawing survives the reduction.

The squeeze was starting in Schulz’s day: Peanuts was the beginning of the “minimalist” look of Cathy and Fox Trot. Watterson’s bold drawing style and appetite for scale posed problems for publishing. Ironically, as Schroeder pointed out in his Q & A, the sort of freedom and flexibility Watterson sought would become available a decade later on the Net.

Something else suffocated comics creativity. Just as tentpole films need an array of ancillaries, a successful cartoon demands the womb-to-tomb merchandising that Watterson foreswore. Children need to be hooked on the franchise before they can read. Garfield clothes and toys introduce infants to a pudgy beast that will stalk them throughout their lives, on lunchboxes and calendars and mugs and mousepads and refrigerator magnets and TV shows and “Is it Friday Yet?” placards for office cubicles. Watterson realized, I think, that being surrounded forever by leering images of cute creatures was one version of Hell.

Schroeder, a graduate of UW—Madison, has made a smart, touching movie. It deserves wide circulation and even, I should say, a PBS airing. It’s at once a tribute to a fine artist, a probe into comics history, and a revelation of how integrity can be maintained in the era of Monetization. Turning down hundreds of millions of dollars, Watterson in effect said something that almost no one imagines possible today: I don’t need that much money.

One observer comments that when Calvin and Hobbes ceased, many critics expected its fan base to dwindle, because it wouldn’t be maintained by all the spinoffs. Instead, parents pass down their Watterson paperbacks as family heirlooms. Fans have the lavish three-volume compendium of the strips, which is selling briskly on Amazon, while school libraries are replenishing their holdings of the slim anthologies. Our children are following the adventures of the hyperkinetic brat and his imaginary tiger in the best way: By reading books.

P.S. 2 May: Chris Blunk of Through a Glass Productions writes this followup:

Coincidentally, this past Sunday I met John Glynn, who works at Andrews/McMeel promoting their properties to Hollywood (such as Garfield and Over the Hedge). He was at the Free State Film Festival in Lawrence, Kansas where he showed the Sundance-boosted Small Apartments, also based on an Andrews/McMeel property. He was the first person I’d ever met who has any kind of semi-regular contact with Watterson. Though Watterson retains nearly all ancillary rights to his characters, A/M-Universal consults him on book printings, electronic distribution, etc.

While there were several tidbits that thrilled a fan like me, one item he mentioned particularly pertained to your article. He claimed that traffic at the Universal comics website (www.gocomics.com) is by and large driven by the Calvin and Hobbes classic – i.e. rerun – strips. The majority of visitors to all other comics on the site – including popular current strips like Get Fuzzy, Pearls Before Swine, Dilbert, etc, – arrive through Calvin and Hobbes.

So in addition to being propagated through handed-down book collections, as you pointed out, Calvin has managed to attract new fans and dominate comics circulation even in the new frontier of the web that grew into being long after Watterson’s retirement. And this with no new strips published in the past 20 years.

He told a couple other anecdotes that were similarly surprising. Such as a time in the early 90s when Spielberg was involved in some animation projects (Tiny Toon Adventures, Family Dog, Animaniacs, etc) and made inquiries about the rights to Calvin and Hobbes. According to Glynn, Watterson turned down a direct phone call with Spielberg himself reasoning they had nothing to discuss.

Thanks to Chris for his thoughts and information, and for reading our blog.

P.P.S. 16 July 2013: Gravitas Ventures announces that it will be releasing Dear Mr. Watterson on theatrical and VOD in November.

Dear Mr. Watterson.

Scoping things out: A new video lecture

A Star Is Born (1954).

DB here:

Cripes! It’s video-lecture fever!

Well, maybe that’s an exaggeration. Still, we do have something new for you.

A video analysis of constructive editing showed up last fall, and a rather long one called “How Motion Pictures Became the Movies” was posted earlier this year. Now comes one on the aesthetics of early CinemaScope in the US.

It’s a new version of a talk now retired from the lecture circuit and snugly cached on the web. I’m hoping both viewers and filmmakers will be interested in this, particularly in its analyses of staging and composition. The piece makes a more general argument about how new technologies offer both advantages and constraints.

“CinemaScope: The Modern Miracle You See without Glasses!” runs about fifty minutes. It’s our first one in HD, so it looks pretty nice on many displays. It could be shown in classes, and I’d be happy if teachers wanted to use it. As with our earlier entries, it’s also available on Vimeo here, where you can leave feedback if you want.

I’m also providing the chapter on Scope from Poetics of Cinema. Think of the lecture as the DVD and the chapter as the accompanying booklet. You can go to the essay if you want to dig deeper into the subject, see other examples of what I’m talking about, or learn the sources for my arguments.

By the way, if you’re interested in the art and craft of widescreen cinema, I’ve posted a web essay on Hong Kong anamorphic here.

As usual, I’m very grateful to my creative tech wranglers Erik Gunneson, who produced the video, and Peter Sengstock. Thanks as well to our web tsarina Meg Hamel.

I’ll have to suspend production of these video lectures for a while, but Kristin and I are hoping to float another novelty soon, perhaps in the next couple of months.

Thanks for everyone who has supported our work through Tweeting, Facebooking, linking, or just telling their friends.

Wild River (1960). From 35mm frame.

Silent films, old and new

Blancanieves

Kristin here:

February and March have been good to silent cinema. Time for a round-up of some highlights as we impatiently anticipate Il Cinema Ritrovato, coming up in a little over two months.

Publications on Albert Capellani

In reporting on the 2010 and 2011 programs of Il Cinema Ritrovato, I highlighted one of the festival’s major revelations, that of the silent films of Albert Capellani. These generous doses of Capellani’s splendid films were put together by Mariann Lewinsky, who realized his importance after she included some of his shorts in her annual “Cento Anni Fa” programs. In my entries I argued that Capellani was revealed as one of the early cinema’s great masters. (The 2010 entry is here, and the 2011 one here.)

Not surprisingly, during the intervening years, scholars have been busy researching Capellani’s films and career. March 6 to 24 saw a major retrospective at the Cinémathèque Française. (Information on the program is still available online, as is a detailed press release.) Shortly before it began, the first biography appeared: Christine Leteux’s Albert Capellani: Cineaste du Romanesque, with a foreword by Kevin Brownlow.

Leteux discovered Capellani in May of 2012, thanks to seeing Notre-Dame de Paris and Les Misérables at the Forum des Images in Paris. Setting out to learn more about the filmmaker, she realized how thoroughly his memory had nearly vanished from film history. She sought out and received the cooperation of his grandson, Bernard Basset-Capellani, whom she describes as “intarissable” (inexhaustible) on the subject.

The result is a solid, traditional biography, with chapters mostly organized around the companies for which Capellani worked (Pathe, SCAGL, World, Mutual, and so on) and some of his key films (Les Misérables, The Red Lantern). The prose style is easily readable French, at least to someone like me with an average knowledge of the language. For an interview with Leteux concerning the book, see here.

The book is on sale at the Cinémathèque’s shop, which unfortunately does not sell online. It was supposed to be available on Amazon.fr, but so far is not. The easiest way for those outside France to order it is through three third-party book-sellers on amazon.fr, all offering it at the cover price of 14.90 €. Leteux’s book is a vital source for anyone interested in early cinema.

I was pleased to see that the last chapter ends with some quotations from my second entry on Capellani, ending with “With the end of the main retrospective, however, it is safe to say that from now on anyone who claims to know early film history will need to be familiar with Capellani’s work.”

The book includes a filmography and list of films available on DVD. These include a new one, a restoration of The Red Lantern by our friends at the Cinematek in Brussels, available on Amazon.fr or directly from the Cinematek’s shop.

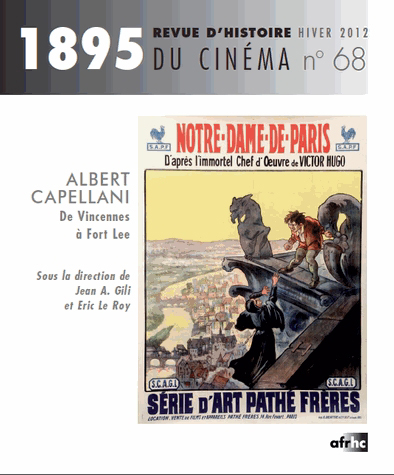

The French-language historical journal on cinema, 1895, timed its March, 2013 issue to coincide with the Cinémathèque’s retrospective. It is entirely devoted to Capellani. I have not had a chance to see it yet, but the table of contents is available here. The only online purchasing source for individual issues I have found is here; the page gives a lengthy summary of the contents.

Mariann continues to search for more surviving prints for restoration and eventual inclusion in future editions of Il Cinema Ritrovato. She has sent me some tantalizing news about recent discoveries and restorations. There will be a third Capellani season in 2014. This will probably include some of the director’s American films: Social Hypocrites (now restored), Flash of the Emerald (the one surviving reel), Inside of the Cup (surviving but so far with no projection print), Eye for Eye (two surviving reals), Sisters, and the French film Le Nabab. Other possible restorations include House of Mirth, La belle limonadiere, and Oh Boy!

A description of the 2013 Ritrovato festival is available here.

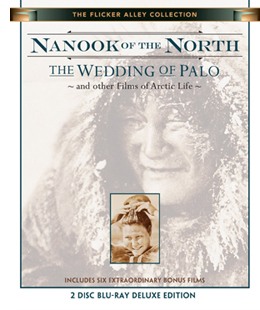

Nanook and friends

Early this year we posted our annual list of the ten best films of ninety years ago. It featured the classic early documentary, Robert Flaherty’s Nanook of the North. In March our friends at Flicker Alley released a two-disc Blu-ray edition of Nanook paired with the 1934 Danish feature, The Wedding of Palo (Palos Brudefærd). The latter is one of those titles that one occasionally encounters on the fringes of older historical surveys, but it has been difficult indeed to see. This new print is a 2012 restoration from a George Eastman House original 35mm nitrate copy.

Nanook is familiar enough, but The Wedding of Palo is not. It was made by the Danish explorer and anthropologist Knud Rasmussen, who appears in a brief introductory passage. Clearly he was influenced by Flaherty’s work. He combines a simple fictional narrative with documentary scenes of traditional Inuit life in eastern Greenland. The basic story involves the heroine Navarona, whose brothers are reluctant to lose their housekeeper by allowing her to marry. Two men of the tribe court her and come into violent jealous conflict. Interjected are sequences of a salmon hunt, a festival, a traditional song duel between the two rivals, and a polar-bear hunt. The staged dialogue scenes involve sound recording, with no subtitles but the occasional brief intertitle to translate.

Nanook is familiar enough, but The Wedding of Palo is not. It was made by the Danish explorer and anthropologist Knud Rasmussen, who appears in a brief introductory passage. Clearly he was influenced by Flaherty’s work. He combines a simple fictional narrative with documentary scenes of traditional Inuit life in eastern Greenland. The basic story involves the heroine Navarona, whose brothers are reluctant to lose their housekeeper by allowing her to marry. Two men of the tribe court her and come into violent jealous conflict. Interjected are sequences of a salmon hunt, a festival, a traditional song duel between the two rivals, and a polar-bear hunt. The staged dialogue scenes involve sound recording, with no subtitles but the occasional brief intertitle to translate.

As in Nanook, the non-professional actors are remarkably natural, especially the “actress” portraying the heroine. There is a cute young boy brought in at intervals for comic appeal, and the members of the village seem always to be laughing and enjoying a suspiciously carefree life. The film has the advantage of more spectacular scenery than that in Flaherty’s film, with huge mountains and glaciers in place of the vast ice-covered vistas (see bottom image).

As usual, the Flicker Alley team has gone beyond the call of duty with this release. It includes not only the two features, but six bonus films, as described in the press release:

Nanook Revisited (Saumialuk) by Claude Massot was made in the same locations used by Flaherty. It shows how Inuit life changed in the intervening decades, how Flaherty consciously depicted a culture which was then already vanishing, and how Nanook is used today to teach the Inuit their heritage. Nanook Revisited was produced in 1988 on standard definition video for French television. Dwellings of the Far North (1928) is the igloo-building sequence of Nanook re-edited and re-titled as an educational film; Arctic Hunt (1913) and extended excerpts from Primitive Love (1927) are by Arctic explorer Frank E. Kleinschmidt; Eskimo Hunters of Northwest Alaska (1949) by Louis deRochemont shows many activities seen in Nanook thirty years after, and Face of the High Arctic (1959) depicts the ecology of the region, produced by the National Film Board of Canada.

Altogether, the films run an impressive 281 minutes. There’s also a booklet with excerpts from Flaherty’s book, My Eskimo Friends, an essay by Lawrence Millman, “Knud Rasmussen and The Wedding of Palo,” and notes on the films.

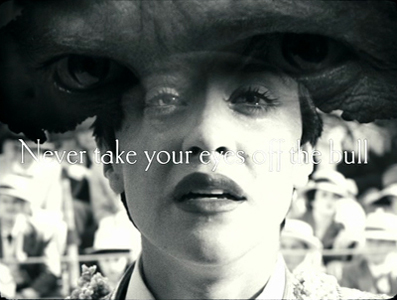

Snow White and the Seven (?) Bullfighting Dwarves

In 2011, a French film, The Artist, gained huge attention in the infotainment media as a modern version of silent cinema, winning yet another Best Picture Oscar for the Weinstein brothers. It was a reasonably successful imitation of mid- to late 1920s cinema during the transition to sound. Now a much better modern silent film has arrived, Pablo Berger’s Blancanieves, a loose version of the Snow White story transposed to 1920s Spain. A famous bullfighter is paralyzed after being gored in the ring. His wife dies in childbirth and his scheming nurse marries him. She keeps his daughter, Carmen, away from her father by setting her to work as a downtrodden servant in his country estate. Upon her father’s death, the evil wife schemes to have her killed, and she escapes to the protection of a troupe of six bullfighting dwarves who, possessing uncertain arithmetic skills, bill themselves as seven bullfighting dwarves.

While The Artist was a fairly good imitation of 1920s Hollywood filmmaking, Blancanieves is a pastiche of the 1928-29 era of European silent cinema. It draws on what I have termed the International Style of filmmaking, a late 1920s blend of influences from the French Impressionism, German Expressionism, and Soviet Montage movements. One could almost pass it off as a genuine film of the era.

At times there are subjective effects à la Impressionism. A superimposition conveys Carmen’s memories of her father’s crucial instructions to her, and superimposed images of hands waving handkerchiefs present the enthusiam of the crowd’s plea for the bull to be pardoned.

This was also the period in which the power of the wide angle lens, particularly in close-ups and in low-angle shots, was exploited, initially in Soviet cinema and then all over Europe. Blancanieves is full of such shots, as in the frame at the top of this entry and in these two shots from the opening scene:

There are also montage sequences, building up to flurries of very short shots. This accelerated-editing technique is typical of both Soviet and French filmmaking of the era.

The too-frequent use of handheld camera in Blancanieves detracts somewhat from the feeling of authenticity. In the late 1920s, cameras were too heavy to be handheld. They could be strapped to the body of the cinematographer with harnesses, but that creates a subtly different look. And during the late 1920s, shots with the camera holding on a character while the background spins around behind him or her would have been achieved by placing both camera and actor on a large turntable. (This effect apparently was pioneered in Germany in the mid-1920s). But the occasional dramatic lighting effects, particularly in the climactic scene, are distinctly reminiscent of German cinema.

In general, the narrative is charming and amusing. The heroine’s pet rooster provides exactly the sort of comic relief that is common in films of the 1920s, and the story has an effective fairy-tale quality. I found the ending a bit disappointing and certainly not typical of the films of the 1920s. Still, Berger has clearly watched an enormous number of 1920s European films and absorbed their styles. He can imitate the International Style remarkably well, telling a tale that is appropriate to the 1920s and yet has a touch of humor that doesn’t belittle the silent era.

Blancanieves was released in the US on March 29 and is currently making the rounds of art-houses and festivals.

Other entries discussing the International Style and wide-angle filming at the end of the silent era can be found here and here.

The Wedding of Palo

“We didn’t have a sense that VERTIGO was special”: Doc Erickson on classic Hollywood

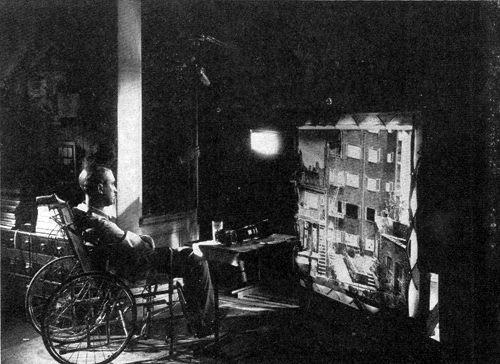

Rear Window (1954); illuminated transparency used to create the lens reflection.

Note: This entry was nearly finished when Roger Ebert died on 4 April. I had intended to send it to him in advance. I think he would want me to post it as I’d planned–just before this year’s Ebertfest.

DB here:

On 17 April, about 1500 people will gather at the Virginia Theatre in Urbana, Illinois, for a celebration of movie love known as Ebertfest. Among Ebertfest’s many guests will be C. O. “Doc” Erickson.

This genial man, who visits Ebertfest each year, is a Hollywood veteran. He was production manager for Alfred Hitchcock, Sidney Lumet, John Huston, Anthony Mann, Roman Polanski, and Ridley Scott. In later years he was associate or executive producer on Chinatown, Urban Cowboy, Popeye, Blade Runner, Looking for Bobby Fischer, Groundhog Day, Kiss the Girls, Windtalkers, and many other projects.

In short, he was an eyewitness to film history. During our visits to Ebertfest Kristin and I have often talked with Doc about his career, and last year I interviewed him for an hour. I thought it was time we set down some of the things we’ve learned. I’ve supplemented Doc’s remarks to us with quotations from Douglas Bell’s 2006 detailed, book-length interview with him.

Setting the scenes

Sunset Boulevard (1950).

Doc began working for Paramount Pictures in December 1944, a year after his graduation from the University of Illinois—Champaign-Urbana. This young man, not yet twenty-one, stepped into the studio that would harbor, across the next few years, The Lost Weekend, The Blue Dahlia, The Strange Love of Martha Ivers, Unconquered, I Walk Alone, A Foreign Affair, Sorry, Wrong Number, The Big Clock, The Heiress, The File on Thelma Jordan, The Furies, Sunset Boulevard, and several Bob Hope, Bing Crosby, and Martin and Lewis comedies.

Initially he worked on estimating the budgets for back-lot and set construction. Doc’s unit would try to give the director some leeway. “Ultimately, it wasn’t [a director’s] fault if the set went over budget. . . . We had to try to get enough money in there so that it wasn’t going to go over budget, because then we’d catch hell.” Then Doc and his colleagues would monitor the building of the set to make sure that the specifications were followed and the budget was adhered to.

Doc moved to stage management and supervision, which required him to plan how a production’s sets were arranged in a sound stage. Four or more sets would have to be fitted together, jigsaw-fashion. Doc would try out arrangements by shifting cutout sets on something like a bulletin board, marked with entrances, walls, and power sources. This was called “spotting the sets.” Spotting was much easier in the days of overhead lighting; lighting from the floor, which became more common as the decade went on, posed extra problems.

Once used, the sets might be dismantled, with different departments rescuing what they could use again. A whole set might be saved for another picture (“fold and hold”). B-pictures recycled sets from A pictures. At the other extreme, ornate interior sets might use units drawn from luxurious houses that had been dismantled. From New York mansions came pieces that were shipped to Hollywood and resassembled to create a salon or ballroom.

Paramount’s back lot included big standing sets, including a train station with some cars on the track. “Then, of course, you had pieces of the train in the scene dock, that could be dragged out and assembled on the stage.” A street at the south end of the lot was used for Westerns and featured a mountain that blocked the view of the adjacent RKO studio.

I’ve long been struck by the fact that articles from the classic period seldom talk about the look of sets for ordinary rooms. So I asked: What colors would be found on the sets in black-and-white movies? Doc smiled. “Black and white—or rather, shades of gray.” Sometimes a bit of green would be added. (I’ve read that sometimes snow was painted yellow to make it dazzle.) Pause and think about how hallucinatory it must have looked: actors moving through a three-dimensional black-and-white movie.

The crew was expected to average fifteen to twenty setups per day, at a period when shooting a top-line feature took anywhere from seven to twelve weeks, or even more. The Paramount policy was to press ahead and finish with a set quickly, even if not every shot was taken. Retakes were likely to be close views of the actors and could be picked up later without need for the full set. This flexibility was feasible because most productions were still shot inside the studio walls. Despite the trend toward location shooting in the late 40s, Doc says, “We weren’t off the lot very much.”

The 1940s saw the rise of the hyphenate filmmaker, and this trend was vigorous at Paramount. The studio roster boasted screenwriter-directors Preston Sturges and Billy Wilder and several director-producers, including Cecil B. DeMille, Mark Sandrich, Mitchell Leisen, and John Farrow. At Paramount, Doc recalls, “The director was king.” No wonder that one of the most kingly figures of the period wound up there for several years.

A step up

The Misfits (1961).

Doc had moved into the role of assistant unit production manager for Secret of the Incas (1954), directed by Jerry Hopper and starring Charlton Heston and Robert Young. His new job involved managing the day-to-day work of filming as a liaison between the production office and the shoot. A production manager works closely with the assistant director to keep the work on schedule and within budget.

When Hitchcock made his five-picture deal with Paramount and was preparing Rear Window, his assistant director, Herbert Coleman, found that all Paramount’s established production managers had been assigned. Coleman asked Doc to take the job, and Hitchcock approved. Doc’s experience with budget estimating and set supervision made him a natural choice for promotion.

Doc supported Hitchcock on several films, becoming a guest at the director’s home and traveling with him. After finishing Vertigo, Hitchcock shifted to studios that had their own personnel for production management. Hitch offered Doc a place on his television series, but Doc moved on to other Paramount pictures: “I wanted to remain in the feature film world.” He worked in Manhattan with Sidney Lumet on That Kind of Woman (1959). Doc admired Lumet’s meticulous planning of every shot, as well as his insistence on table readings of the whole film before shooting.

Doc then teamed up with John Huston. In 1959 Huston was trying to launch The Man Who Would Be King, and for location scouting he took Doc and other team members on a forty-day trip around the world, paid for by Universal. But that project was put on hold. Doc went on to manage production for The Misfits (1961), Freud (1962), and Reflections in a Golden Eye (1967). On the latter two films, Elizabeth Taylor lobbied for Montgomery Clift—winning on Freud, losing on Reflections. (Brando got the part.)

Knowing my interests, Doc pointed out some of Huston’s directorial touches, including some striking uses of deep space. In the image above, Montgomery Clift’s quarrel with the rodeo judge is framed in the car window while Marilyn Monroe frets that he could have died in his fall from the bull. Doc also thinks that Huston showed adroit staging in the Reflections scene showing Brian Keith wiping lipstick off his mouth while Elizabeth Taylor, in the back seat, uses the rearview mirror to help her repaint her lips.

The movie industry was pushing toward ever more spectacular projects, and Doc sometimes went epic. After a production manager on 55 Days at Peking (1963) quit, the film’s editor, Robert Lawrence, suggested Doc. The film’s direction was credited to Nicholas Ray, but the bulk of the footage was shot by Andrew Marton. There followed Doc’s stint on The Fall of the Roman Empire (1964). He recalls Anthony Mann’s excellent eye for composition. The most tangled production was Cleopatra (1963), which had begun shooting in 1960 and was plagued with constant delays. Doc was there for the last eight months of shooting, up to August 1962. He worked under Lewis Merman, the Fox production manager (“one of the greatest human beings I’ve ever known”). Merman was also known as Doc, so the production had both a Big Doc and a Little Doc. It needed even more docs.

Hitch

For my current research I asked Doc a lot about 1940s studio practices, but I couldn’t avoid touching on what everybody asks him about. How was working with Hitchcock? Hitchcock productions have been chronicled in detail by many writers, so I’ll just pick some bits that Doc brought out for me.

On Rear Window (1954), Doc’s expertise in squeezing sets into a sound stage came in handy. The script demanded that the camera be confined to Scottie’s apartment and that we see only what could be seen from that room. Remarkably, Doc recalls no matte shots being used on the production. The apartment, the courtyard outside, and the apartment building opposite were all installed on a single stage.

Doc was struck by the lighting limitations of this complex and confined set. The color film stock was quite slow, and so illumination levels were very high. He told Douglas Bell:

We had to pour so much light into those apartments, up where Raymond Burr was, it almost put him on fire. It was terrible. Or you would never be able to see him, from where we were shooting. . . . But today it would be nothing, it would be a cinch.

Lens length was also a problem because the camera couldn’t easily simulate the telephoto view of the apartment across the courtyard. Doc found a way to mount the camera outside the window to get a little closer to the opposite building and suggest the enlargement provided by Scottie’s long lens.

Hitchcock had claimed he would need only twenty-four days to shoot Rear Window, but it ran to thirty-six, and its cost was considerably beyond what he had estimated. So great was Hitchcock’s standing in the industry that Paramount didn’t object, knowing the result would be a major picture. Doc was on the set every day. Hitchcock would position the actors and frame the shot, but then return to his chair to watch.

Hitchcock liked Doc and picked him again for To Catch a Thief (1955). For this they left the studio and shot on the Riviera for several weeks—Doc’s first location shoot. After the on-site filming was finished, Hitchcock returned to Paramount for studio scenes and Doc stayed to oversee helicopter shots of the roadways with special-effects specialist Wallace Kelly. The team followed the famous Hitchcock lists and storyboards for such second-unit footage.

Without a break Hitchcock drafted Doc for The Trouble with Harry (1956). Originally to be set in England, the story was transposed to New England. Despite some location work, there were a surprising number of studio exteriors (as are quite obvious to our eyes today). Doc supervised the building of woods on Stage 14, but then scattered around leaves brought in from Vermont and New Hampshire.

Doc was involved in scouting locations in Marrakech and London for The Man Who Knew Too Much (1956), along with assisting Coleman and Hitchcock in the usual way. Hitchcock clashed with John Michael Hayes on the project, and according to Doc, Steven Derosa’s account of the contretemps in Writing with Hitchcock does justice to the complexity of the situation.

Doc’s memories of the master’s next production, Vertigo, are detailed, but they and other participants’ accounts are chronicled in Dan Auiler’s Vertigo: The Making of a Hitchcock Classic. What I found surprising were two of Doc’s responses to the project. Doc found that the production went very easily. He thinks that was because he had learned so much about location shooting with the overseas demands of To Catch a Thief and The Man Who Knew Too Much. My second surprise: “We had no sense that Vertigo was special.”

I’m out of step with the world’s critical consensus. I wouldn’t consider Vertigo the best film of all time, or even the best film by Hitchcock. (My votes would go to Shadow of a Doubt, Notorious, Rear Window, and Psycho. All seem to me perfect, endlessly exhilarating pictures.) To a great extent, I think that American Hitchcock never stopped being a 40s director, so I tend to see Vertigo as an uneven mix of plot elements and visual ideas from that wild era. Good as the film is, I think, the expository scenes are rather flatly filmed and lack the flair that Hitchcock brought to such scenes in his earlier films.

But thanks to the undeniable brilliance of many other scenes, along with the revolution of taste promoted by the Cahiers du cinéma critics and the long suppression of the film (making it a sought-after treasure), Vertigo has become a holy grail of obsessional cinema. Its plot premise has fed cinephiles’ fantasies. In the history of taste, a fairly creaky tale of murderous deception has become the ultimate vessel of filmic fascination. One hero’s delusion now epitomizes all movie-made illusion.

Give Doc the last word: “When we finished Vertigo, we never thought of it as being the film that everybody thinks it is today. It’s become bigger than life itself.”

Thanks to Doc Erickson for affable and informative conversations.

Being mostly interested in the Old Hollywood, Kristin and I didn’t question Doc about his work of more recent decades. Those activities are covered in Douglas Bell’s extensive interview, recorded in An Oral History with C. O. Erickson (Los Angeles: Academy of Motion Picture Arts, Margaret Herrick Library, 2006). I’ve drawn much information from this volume. I thank Jenny Romero, Special Collections Department Coordinator at the Herrick Library, for facilitating access to it, and to Kristin for examining it for me during her recent visits to Los Angeles.

For a detailed account of the division of labor on 55 Days at Peking, see Bernard Eisenschitz, Nicholas Ray: An American Journey, trans. Tom Milne (Faber, 1993), 378-389. Andrew Marton, who took over the shoot after Nicholas Ray was dismissed, estimated that sixty to sixty-five percent of the finished film was his work. See Andrew Marton Interviewed by Joanne D’Annunzio: A Directors Guild of America Oral History, 413-418.

Herbert Coleman’s book The Hollywood I Knew: A Memoir: 1916-1988, revisits his AD work with Hitchcock in considerable detail, and many of the anecdotes he recounts involve Doc Erickson. For more on the production of Hitchcock’s films, see Patrick McGilligan’s Alfred Hitchcock: A Life in Darkness and Light and Bill Krohn’s Hitchcock at Work.

Without any planning, the last six months or so have been this blog’s Hitchcock period. The entries include items on Dial M for Murder (screened at the Toronto International Film Festival last September), on David O. Selznick, on the first Man Who Knew Too Much, and on the rise of the suspense thriller during the 1940s. On Lumet, for whom Doc also worked, you can see this entry. The production photographs in today’s entry are taken from Arthur S. Gavin, “Rear Window,” American Cinematographer 35, 2 (February 1954), 76-78.

Kristin and Doc Erickson, Ebertfest 2009.