Archive for May 2013

On the more or less plausible sneakiness of one Preston Sturges

The Miracle of Morgan’s Creek (1944).

DB here:

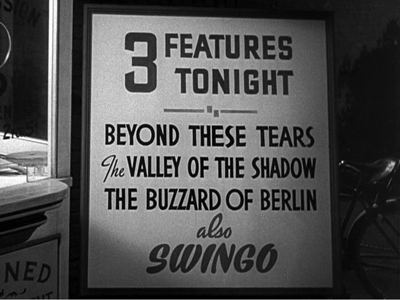

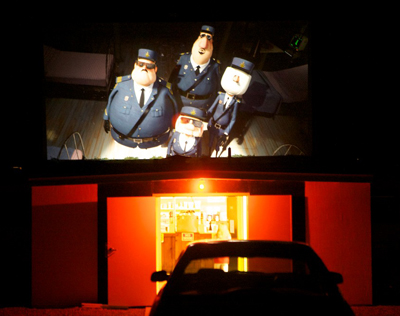

It’s no news that Preston Sturges occasionally mocked the film industry. Exhibit A is Sullivan’s Travels (1941), in which a director of escapist comedies decides to switch to serious social commentary. Sturges’ movie starts with a parody of a violent Hollywood climax that ends with two men plunging to their death. Next we’re told that Sullivan’s previous triumphs are Hey, Hey in the Hay Loft, Ants in Your Plants of 1939, and So Long, Sarong. At a later point we see a somewhat more somber triple feature:

“Swingo” is Sturges’ equivalent of Screeno and other 1930s Bingo-like games designed to lure audiences into theatres.

These gags are pretty straightforward. While working on my book on Hollywood in the 1940s, I found that The Miracle of Morgan’s Creek (1944) offers us something less obvious and more peculiar.

Three big fake features

Norval Jones (Eddie Bracken) has taken Trudy Kockenlocker (Betty Hutton) out on a date. They’ve told her highly combustible father (William Demarest) they’re going to the movies. Actually her plan is to sneak away and celebrate with soldiers about to be sent overseas. She convinces Norval to cover for her and to loan her his car. Trudy is gone all night. Drunk, pregnant, and now married to an elusive Ignatz Ratzkiwatzki, she drives up to find Norval sleeping curled up in the foyer of the movie house. In the two scenes around the Morgan’s Creek Regent theatre, Sturges wedges in some barely noticeable jabs and in-jokes.

Start with what’s playing. Four posters are in the foyer around the box office. One is sitting on an easel turned largely away from us. The other three are mostly blocked by actors, partially framed, or thrown out of focus. But by freezing the film we can make out the titles of these three fakes.

The most visible film is Chaos over Taos, clearly a Paramount release.

You can also make out The Private and the Public, which also bears the Paramount logo. Its poster is behind Norval. Much harder to discern is the title of the third feature on the program, Maggie of the Marines. It’s barely visible for a few frames, glimpsed over Trudy’s right shoulder.

Knowing Sturges’ penchant for playfulness, we can see two of these as parodies of Paramount releases. The Private and the Public seems clearly a reference to The Major and the Minor, directed by Billy Wilder and released in early fall of 1942. Sturges began shooting Morgan’s Creek in October of that year and finished in early 1943, so he would have been well aware of the Wilder film. As an extra fillip, the star of The Private and the Public is listed as Fred McMany, a reference to Paramount star Fred MacMurray.

Then there’s Chaos over Taos. The title is weird enough, relying on an eye-rhyme and being so tough to pronounce that no studio would ever choose it. The star names, Armando Torez and Maria Robles, don’t suggest any Paramount contract players to me, but this was the period when Hispanic and Latino stars began to headline Hollywood movies: Carmen Miranda, Lupé Velez, and Cesar Romero are the most famous. Emphasizing Latin American plots, players, and locations was part of Hollywood’s contribution to Roosevelt’s Good Neighbor policy. The effort was seen most famously in Disney’s wonderful Saludos Amigos cartoon (1942) but also in a series of Fox musicals with cities named in the titles (Down Argentine Way, That Night in Rio, Week-end in Havana). Chaos over Taos could be Sturges’ dig at a then-current trend in political correctness and at another studio’s production cycle. As for the genre, Chaos/Taos is a flyboy movie and Paramount made several of those—three B-films in 1941 alone (Flying Blind, Forced Landing, and Power Dive, all featuring Richard Arlen).

What then of Maggie of the Marines? It’s likely that Sturges grabbed the title from an October 1942 news story about a dog that wandered into a marine camp in the Panama Canal. Details are at the bottom of today’s entry. We can imagine the sort of heart-warming comedy it might have been, as long as Sturges wasn’t at the helm.

Etc., etc., and etc.

Finally, there’s a matter of exhibition. Just as in Sullivan, the theatre in The Miracle of Morgan’s Creek proclaims a very long show: “3 Big Features Tonight, Short Subjects, Newsreel, and Boxo” (another mockery of Screeno). Norval tells Trudy that the whole shebang is scheduled to end at about 1:10.

Unlike the bill of fare in Sullivan’s Travels, the long show at Morgan’s Creek motivates plot action. Trudy uses the pretext of a long triple feature to get her father’s permission to stay out late. But it may not be too much to see in Sturges’ interest in triple features another contemporary reference.

Triple features emerged in the mid-1930s, partly because of high output from the studios and partly because of competition among exhibitors. Dan Goldberg wrote in Variety in 1938:

In a wild scramble for immediate returns without any thought to the outcome, the exhibitors have tried freaks and stunts rather than policy and operation. There have been double features, triple features, bank nite, screeno, keeno, bingo, and giveaways of all kinds, including dishes, flatware, linenware, framed pictures, wall plaques, etc., etc., and etc. There are many houses around here [Chicago] which are getting a 15c and 20c admission and giving away merchandise valued at 11c and more.

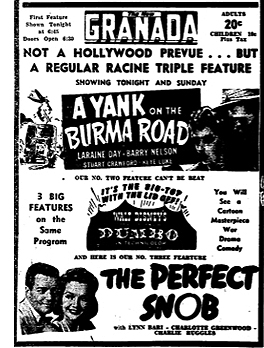

The studios hated double-feature programs but the public, voting its wallet, preferred them. Duals, as they were called, were largely a subsequent-run phenomenon, but because of the vast number of releases and block booking, they crept into first-run venues too. Triple bills were far less common and typically included two or even three B pictures. Most A-grade pictures aimed to come in under 100 minutes, and a B was typically sixty to seventy minutes long, so a triple feature of an A and two Bs wouldn’t be stupendously long. In the Racine triple feature on the right, two Bs flank Dumbo, a 62-minute movie, and the whole program, without shorts, trailers, and intermissions, would last only a little over three hours. Many triple bills seem to have consisted of three Bs. Sometimes the movies weren’t all features: a cartoon or a serial episode might be counted as one of the “Three Big Hits” advertised.

The studios hated double-feature programs but the public, voting its wallet, preferred them. Duals, as they were called, were largely a subsequent-run phenomenon, but because of the vast number of releases and block booking, they crept into first-run venues too. Triple bills were far less common and typically included two or even three B pictures. Most A-grade pictures aimed to come in under 100 minutes, and a B was typically sixty to seventy minutes long, so a triple feature of an A and two Bs wouldn’t be stupendously long. In the Racine triple feature on the right, two Bs flank Dumbo, a 62-minute movie, and the whole program, without shorts, trailers, and intermissions, would last only a little over three hours. Many triple bills seem to have consisted of three Bs. Sometimes the movies weren’t all features: a cartoon or a serial episode might be counted as one of the “Three Big Hits” advertised.

Triples were evidently less popular with audiences than duals. Perhaps people weren’t willing to spare such a big block of time, or they suspected that the lesser items on the bill weren’t worth watching. Jeff Smith suggests to me that adding a B to an A looks like a bonus, but two or three Bs look like a dumping ground. Interestingly, when Trudy tells Norval she plans to skip out on him, he protests: “I won’t do it! I won’t sit through three features all by myself.” Trudy asks plaintively: “Couldn’t you sleep through a couple of ’em?”

While Sturges was preparing Morgan’s Creek, he might well have noticed some Variety stories tracing a controversy about triple bills in the Midwest. A chain in St. Louis had shifted to this policy, and to retaliate a rival chain began four-hour shows consisting of two features and sixty minutes of shorts. In late 1940, a civic group, the Better Films Council of Greater St. Louis, put pressure on exhibitors to oppose long programs. The Council claimed that such bills were “a physical and mental strain on children and young people,” and that family-appropriate films were sometimes accompanied by “adult” ones. Getting no cooperation from the theatre circuits, the Better Film Council announced in early 1941 that it was going to introduce state legislation to ban triple features. This effort evidently came to nothing.

As if in response to bluenose worries about long programs, Sturges gives the lucky Morgan’s Creek patrons a movie banquet that ends in the wee hours. And ironically, Trudy would have suffered less “physical and mental strain” in the days and weeks thereafter if she’d gone to the movies and not kissed the boys goodbye. The Regent’s absurdly inflated program may be Sturges’ dig at both a contemporary trend and those who fretted about it.

Watching me rake these apparently innocuous frames, you may be asking: Is David going all Room-237 on us? Actually, I see today’s entry as in the spirit of an earlier one, which also has an enigmatic Sturges connection. I’m interested in the moments when Hollywood is talking to itself.

We tend to think that the studios made movies to communicate with the public, and that’s surely true. But we tend to forget that filmmakers were sometimes talking to each other. In the Zanuck-produced Hollywood Cavalcade (1939), a romance of silent-era moviemaking, director Don Ameche turns down Rin-Tin-Tin for a project. The obvious joke is that the pooch became a big star, but how many viewers would appreciate the in-joke that Zanuck launched his career at Warners writing scripts for Rinty? Did the public know that Slim and Steve, the nicknames swapped between Bogart and Bacall in To Have and Have Not, were the ones used by Hawks and his wife? Would ordinary moviegoers catch the reference to Archie Leach in His Girl Friday or notice Jed Leland’s column in the newspaper in The Magnificent Ambersons?

Some would have. Moviegoers of the day were better-educated than the populace in general, and the biggest fans went several times every week. But even if the audience missed these bits, the filmmakers’ peers might not. These movies were made by youngish people who liked to have fun–sometimes at each other’s expense—and nothing is more fun than very esoteric in-jokes.

The problem is that these other examples are highlighted in dialogue, but some of Miracle‘s in-jokes are almost completely buried. They’re more akin to the current vogue for Easter Eggs in sets and props. Unlike the recent instances, though, Sturges’s hints are hard to catch during projection, and he couldn’t have counted on viewers mulling over them frame by frame, as our directors can.

Perhaps he intended to show those posters more fully but had to forego that option during filming or cutting. Or perhaps he included them just for his own amusement–that is, not for the general public, nor even for his peers, but merely for the pleasure of putting in things that only he and his team knew about. If that seems implausible, let me ask: If you could do it, wouldn’t you?

The fourth poster, after some fiddling with the Skew and Perspective tools in PhotoShop, reveals itself as another aerial adventure: Eagle something…. Eagle Blood, maybe? For an example of a drama using real film titles in its movie marquees, see this entry.

On duals and triples, see “Triple Features Seen as Nabes’ Salvation,” Variety (22 January 1935), 3; Dan Goldberg, “Chicago Merry-Go-Round,” Variety 24 October 1938, p. 21; “Now It’s Duals, with Vaudeville, At the Loop Oriental,” Variety (25 January 1939), 5; “Single-Billing Idea Up Again But Practically It’s Still NSG,” Variety (26 August 1942), 13. On the St. Louis controversy, see “Better Film Council Queries St. L. Exhibs on Duals and Triples” Variety (23 October 1940), 21, and “St. Louis Group Seeks to Outlaw Triple Features,” Variety (26 February 1941), 21.

The embedded ad for a triple feature comes from The Racine Journal-Times (11 July 1942), 8.

No need to write me about the most obvious in-joke in Morgan’s Creek: the fact that it incorporates two major characters from The Great McGinty (1940) and doesn’t even bother to credit the actors. Cheeky, this Sturges fellow.

From The Daily Gazette (Berkeley , California, 19 October 1942).

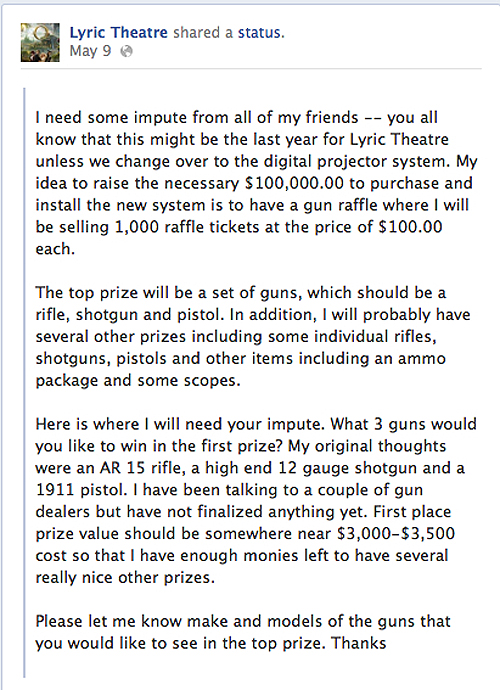

The annals of showmanship: Any popcorn or ammo with your Pepsi?

Albatros soars

Gribiche (1925).

Kristin here:

Lazare Meerson was one of the great set designers of the late silent period and into the 1930s. His name may not immediately ring a bell, but he designed the great French films of René Clair (La Proie du vent, An Italian Straw Hat, Les deux timides, Sous les toits de Paris, Le Million, À nous la liberté, and La Quatorze Juilliet) and Jacques Feyder (Gribiche [above], Carmen, Les Nouveaux Messieurs, Le Grand Jeu, Pensions Mimosas, and La Kermesse héroïque). He crossed paths with most of the major French Impressionist directors, sometimes in their post-Impressionist periods: Marcel L’Herbier (Feu Mathias Pascal, his masterpiece L’Argent, Le Mystère de la chambre jaune, and Le parfum de la dame en soi), Jean Epstein ( Les Aventures de Robert Macaire), and Abel Gance (Le fin du monde and Poliche). His credits include work with such French directors as Maurice Tourneur, Julien Duvivier, and Claude Autant-Lara.

Meerson was born in Russia and fled the Revolution. Making his way via Germany to Paris, he became the assistant to set designer Alberto Cavalcanti on Feu Mathias Pascal. That’s one of the five French films on a new Flicker Alley release, “From Moscow to Montreuil: The Russian Émigrés in Paris: 1920-1929.” Meerson’s illustrious career led him to England in the second half of the 1930s, where he designed several notable films, including Paul Czinner’s As You Like It, Clair’s Break the News, and Feyder’s Knight without Armour, as well as the classic The Scarlet Pimpernel. He died in 1938 at the young age of 38. (The best online source on Meerson is R. F. Cousins’ filmography, bibliography, and brief biography.) His influence lives on in the work of his most prominent student, Alexandre Trauner (Le jour se lève, among many others).

I begin with Meerson in order to stress how many important strands of film history come together in this very ambitious Flicker Alley set. It allows us to trace Meerson’s early years, from his first apprentice work, Feu Mathias Pascal, to his first and third projects for Feyder. That in itself would be enough to make this release notable, but the Albatros film studio in Paris during the 1920s hosted an amazing collection of talented people working in the cutting-edge styles of the era.

Here we also find three films starring the extraordinary Russian star Ivan Mosjoukine, known to most audiences by reputation only, and then only for the ephemeral Kuleshov experiment that used footage from an old film with Mosjoukine.  This experiment is not known to survive. In it a close view his impassive face reputedly was edited together with shots of a dead woman, a bowl of soup, a small child, or perhaps other subjects, depending on which report you read. Spectators supposedly credited Mosjoukine with a marvelous performance, based on eyeline editing rather than any changes in his expression. We shall probably never know the exact form this experiment took and who saw it. I have to believe that the shots of Mosjoukine were inserted at wide intervals in a feature film, not strung together one right after the other, as makers of modern “reconstructions” of the experiment seem to assume. It’s much more interesting to watch Mosjoukine in the three very different performances presented here: Le Brasier Ardent, Kean, and Feu Mathias Pascal. His face is anything but impassive

This experiment is not known to survive. In it a close view his impassive face reputedly was edited together with shots of a dead woman, a bowl of soup, a small child, or perhaps other subjects, depending on which report you read. Spectators supposedly credited Mosjoukine with a marvelous performance, based on eyeline editing rather than any changes in his expression. We shall probably never know the exact form this experiment took and who saw it. I have to believe that the shots of Mosjoukine were inserted at wide intervals in a feature film, not strung together one right after the other, as makers of modern “reconstructions” of the experiment seem to assume. It’s much more interesting to watch Mosjoukine in the three very different performances presented here: Le Brasier Ardent, Kean, and Feu Mathias Pascal. His face is anything but impassive

We can also appreciate Belgian-born director Jacques Feyder, who had begun his feature-film career with L’Atlantide (1921) and Crainquebille (on our 10-best list for 1922) and then suffered a box-office disappointment with the charming, poignant Visages d’enfants, making two notable films for Albatros. Gribiche contains the first performance by Françoise Rosay, Feyder’s wife, who became one of the grandes dames of French cinema.

Most of all, however, this set makes a big step in showing us what happened after the Revolution to the most important Russian production company, that of Josef Ermolieff. The founder, as Lenny Borger points out in the highly informative booklet accompanying the set, had French connections from the start. Ermolieff “begin his career as a technical assistant at Pathé’s Moscow branch, and by 1912 had moved up through the ranks to become Pathé’s sales agent in Russia. On the verge of the war, he founded his own company and studio and gathered around him a core of artists and technicians who later would become the Russian film colony of Paris.”

The Russian work of the Ermolieff company was revealed to modern audiences in the groundbreaking retrospective of pre-Revolutionary Russian cinema presented at the La Giornate del Cinema Muto festival in Pordenone, Italy in 1989. The flood of hitherto unknown films included great melodramas starring Mosjoukine and other wonderful actors who made their way to Paris in the wake of the Revolution.

Ermolieff initially took his company to Yalta, where in 1918-19, they made several films. The next stop was Constantinople, and finally Paris via Marseilles. Ermolieff purchased the old Pathé studio in Montreuil-sous-Bois and set up filmmaking. The first film entirely produced there, Yakob Protazanov’s L’Angoissante aventure (1920) is not included in the Flicker Alley set. It does survive, however. I remember it as an entertaining film with the added attraction of having a story built around filmmaking. Perhaps someday that, too, can be made available on DVD. In the meantime, the five films in the set show the Russian emigrés gradually merging with the French filmmaking establishment of the day and supporting the work of some of the important Impressionist filmmakers.

Ermolieff himself decided to set up shop in Germany, selling the studio to two of his colleagues, Alexandre Kamenka and Noë Bloch. Renaming the firm Les Film Albatros, they brought it into the mainstream of French cinema.

Le brasier ardent (1923)

Mosjoukine directed two films, of which this is the second. It has a reputation as an audacious, surrealist, and almost incomprehensible film. This may be due to the fact that prints available in archives during the 1970s and 1980s lacked intertitles. The opening nightmare sequence is indeed disturbing, but at least with intertitles, we understand that it is only a dream. It begins with a wild-eyed man tied to a stake where he is about to be burned. The heroine stands looking on, resisting as the man pulls on her long hair, apparently intent on dragging her into the fatal flames to accompany him in death. Subsequent scenes of the nightmare show the heroine encountering different men, all played by Mosjoukine, culminating in a man in evening dress stalking her along a vaguely Expressionist street until she escapes and wakes up in bed.

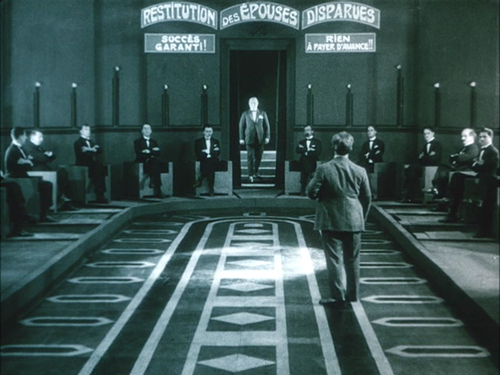

This nightmarish opening must have established vivid expectations in the spectators of 1923 as to what sort of film they were in for. After the heroine wakes up, however, what follows is quite different. The main plot is a stylized but quite amusing comedy. The heroine is a pampered wife, married to a rich man whom she does not love. She is faithful, but he is unreasonably jealous. He goes to a distinctly odd detective agency, one department of which is “Recovery of Lost Wives” (above), with “Success guaranteed!” and “Nothing to pay in advance!” Juxtaposed with the bizarre opening, this quirky humor might have eluded puzzled audiences of the day. Certainly the film itself was a failure, and Mosjoukine stuck to acting thereafter.

Unfortunately for the husband, Detective Z, whom he picks from the eccentric group pictured above, is the very man, again played by Mosjoukine, whom his wife has dreamed about. What follows is an odd tale with the detective and wife gradually falling love. Mosjoukine, known for his tragic, intense characters in the Russian cinema, plays such figures in the fantasy sequences–but in the main story he is allowed to play for laughs, gamboling and rolling on the floor like a puppy when the wife finally appears at his mother’s apartment and declares her love for him.

Mosjoukine should not, however, be allowed to overshadow his co-stars, Ermolieff actors who were also were to make their way into the wider French production of the day, including Impressionism. The wife is played by Nathalie Lissenko, one of the stars of the pre-Revolutionary cinema, who had acted opposite Mosjoukine in Russia. Among her 1920s roles was the protagonist of one of Epstein’s finest films, the largely unknown L’Affiche (1924). The husband is Nicolas Koline, who started his career with Ermolieff only after the company had left the Soviet Union. He will be familiar to silent-film fans from his performance as Tristan Fleury in Gance’s Napoléon.

Kean (1923)

Le Brasier ardent has definite touches of the Impressionist style, but Alexandre Volkoff’s big-budget biopic Kean went further in that direction. I have to admit that it’s not one of my favorite Albatros films. Borger points out that, although it was a prestige picture in its day and quite successful, it has not worn well. The fault in part may lay in the source material, a play co-authored by Alexandre Dumas. Still, the film is notable for Mosjoukine’s anguished performance as the great Shakespearean actor. It also contains one of the most famous sequences of the Impressionist movement, where Kean gets drunk and dances frantically. Borger describes it: “The increasingly frenzied cutting that translate his state of mind was not there by chance: since the trade screenings of Abel Gance’s La Roue [also released by Flicker Alley] a few months prior to the shooting of Kean, rapid-cutting had become all the rage in French films–look at some of the major commercial pictures produced after La Roue’s release and you will find at least one obligatory explosion of rapid editing. But Volkoff was Gance’s best imitator.”

Feu Mathias Pascal (1925)

To quote myself from an article in the issue of Griffithiana devoted to the 1989 Pordenone retrospective:

These two films abruptly brought the Albatros group to the attention of the Impressionist directors and to supporters of the French avant-garde cinema. After having virtually ignored the Russian emigrés to this date, Cinéa published a long article on Le Brasier ardent and an interview with Mosjoukine; Kean received similar attention, and articles in Cinéa-Ciné pour tous and Cinémagazine appeared reguarly thereafter. After this point, Mosjoukine starred in films by the French Impressionists as well as those by emigré directors: Le Lion des Mogols, for Epstein, Feu Mathias Pascal, for L’Herbier, and, nearly, in Napoléon, for Gance.

For decades Feu Mathias Pascal was the most familiar of L’Herbier’s films, at least in the USA, where an abridged version was part of the Museum of Modern Art’s circulating 16mm collection. By now his L’Argent (1928) has probably eclipsed the earlier film’s reputation, at least in the eyes of critics, historians, and silent-film enthusiasts. Feu Mathias Pascal is a more approachable film, though, and would be a good choice for teaching French Impressionism.

Adapted from a novel by Pirandello, it stars Mosjoukine as a character described at the outset: “From childhood Mathias Pascal, a tormented dreamer, has cherished a fantastic hope to free himself to become his own Master!” This paves the way for the many dreams, visions, and heightened emotional states that will be conveyed by the superimpositions, selective focus, camera movements, and fast cutting beloved of the Impressionists.

Pascal finds himself in exactly the sort of situation he hates: tormented by his overbearing mother-in-law and by a wife too weak to side with him against her. His mother and infant daughter both die, and grief-stricken, he flees. A large win at a casino and a mistaken identification of the body of a suicide as Pascal lead him to seize the opportunity to begins a new life.

Mosjoukine left Albatros after this film, pursuing his stardom in big-budget exotic historical films and melodramas, including work in Hollywood and Germany, before his death in 1939 at the age of 49. This was also Michel Simon’s first significant film; he appears in an important supporting role.

Gribiche (1925)

Gribiche is a charming film built around the talents of the boy actor Jean Forest, whom Feyder had discovered for a small role in Crainquebille.

He plays Antoine, nicknamed “Gribiche,” the son of a war widow who struggles to support him and keep him in school. As the film opens, Gribiche returns the dropped purse of a rich woman, Mme. Maranet (Françoise Rosay), and refuses the proffered reward. Maranet, having a scientific interest in children’s welfare, on a whim offers to adopt him. Knowing that his mother is being courted by Philippe Gavary, whom she hopes to marry, Gribiche pretends to want the private education promised by Maranet, and off he goes to live in her modern mansion (Meerson’s design, see top). There he is raised by servants and tutors to a strict schedule, with no time allowed for play. Meanwhile, his mother becomes engaged to her suitor.

The story contains some implausibilities. During a fairground outing with his mother and Gavary (above), Gribiche overhears the two discussing a possible marriage, but both seem worried about Gribiche. There is a hint that the man won’t propose if he has to take on a stepson. This scene motivates the whole chain of affairs. Yet Gavary seems to like the boy, and when Gribiche gets fed up with his sterile life with Maranet and runs away, Gavary is concerned and willing to take him in with no hint of discord between him and the mother. Still, the story on the whole is carried by Forest’s ability to play for both humor and pathos, the beautiful Meerson settings, and the comic business with the tutors and servants. Rosay remarkably creates a character who is friendly and sympathetic yet lacks the deeper warmth that would allow her to raise a child.

For those not familiar with Feyder’s early work, this and the next item are musts. His three most important earlier films are available on DVD, so much of the director’s silent career, previously little known, is now accessible.

Les Nouveaux Messieurs (1928)

This is a Feyder work well worth getting to know. Moving beyond his films based on stories of innocents oppressed (Crainquebille, Visages d’enfants, and Gribiche), Feyder made an adaptation of Carmen (1926) that is competent but not exciting and Thérèse Raquin (1928), which to the best of my knowledge does not survive.

Les Nouveaux Messieurs was an adaptation of a different kind, one which Borger quite rightly compares to René Clair’s late silent comedies. Taken from a popular play of the 1925-26 season, it is a satirical comedy about Jacques Gaillac, an electrician who runs for public office and briefly ends up as labor minister in a leftist government. Along the way he courts Suzanne, a ballerina who is the mistress of the wealthy Count of Montoire-Grandpré. The Count is an older man who is patiently resigned to fighting off her occasional suitors, and we see him pulling political strings on the sly.

Once again Feyder displays his talent for casting actors who can build sympathy for characters who would normally register as unpleasant. Gaby Morlay makes the mercenary ballerina appealing, someone we can believe the naïve electrician would fall in love with. Veteran actor Henri Roussell is remarkable as the Count, eschewing the obvious tropes of anger and jealousy. He is instead smart, amusing, and clearly so devoted to Suzanne that we half hope she will go back to him. The film again has Meerson settings and displays Feyder’s eye for striking visuals, both on location (above) and in the studio (below).

I recently mentioned in my discussion of Blancenieves that it was an excellent imitation of a European film made in 1928 or 1929. Les Nouveaux Messieurs is a good example of the kind of film it’s modeled on.

Coming up

Flicker Alley recently revealed that it has three releases nominated for awards in Il Cinema Ritrovato’s annual DVD awards for 2013, winners to be announced at the festival this year. Oddly, I can’t find a list of all the nominees online. When it appears, I’ll add it. The Flicker Alley nominees are: Nanook of the North/The Wedding of Palo, Feu Mathias Pascal, and “From Moscow to Montreuil.” Congratulations!

Now, if Flicker Alley will manage to release its long-rumored project, Albatros’s 1923 serial, La Maison du mystère, starring Mosjoukine, we will all be doubly grateful. For a bit of information on that and a great deal of information on various film-preservation topics, see this interview with David Shepherd, preservation expert and co-producer with Jeffery Masino of “From Moscow to Montreuil.” Nitrateville has posted a shorter interview with Shepherd, but one devoted entirely to the Albatros release.

Finally, readers who use Facebook should consider Liking Flicker Alley’s page. It lists public screenings of silent films, sponsored by itself and others alike, as well as other silent-film-related news and information about Flicker Alley releases.

The most comprehensive publication on Albatros is François Albera’s Albatros: des Russes à Paris 1919-1929 (Paris: Cinémathèque française, 1995), which contains numerous designs and on-set production photos.

My article is “The Ermolieff Group in Paris: Exile, Impressionism, Internationalism,” Griffithiana 35/36 (October 1989), pp. 50-57. (The quotation is from pages 52-53.) Lenny Borger’s “From Moscow to Montreuil: the Russian Emigrés in Paris 1920-1929,” appears in the same issue, pages 28-39, including a filmography.

Flicker Alley recently released Feu Mathias Pascal separately in a Blu-ray version.

Les Nouveaux Messieurs (1928).

Pandora’s digital box: End times

35mm projection booth at Market Square Cinema, Madison, Wisconsin; 10 May 2013.

DB here:

When exactly did film end? According to the mass-market press, here are some terminal dates.

July 2011: Technicolor closes its Los Angeles laboratory.

October 2011: Panavision, Aaton, and Arri all announce that they will stop manufacturing film cameras.

November 2011: Twentieth Century Fox sends out a letter asserting that it will cease supplying theatres with 35mm prints “within the next year or two.”

January 2012: Eastman Kodak files for bankruptcy protection.

March 2013: Fuji stops selling negative and positive film stock for 35mm photography.

Each of these events looked like turning points, but now they seem merely phases within a gradual shift. After all, the digital conversion of cinema has been in the works for about fifteen years. The key events–the formation of a studio consortium to set standards, the cooperation of technical agencies and professional associations, the lobbying for 3D by top-money directors–didn’t get as much coverage. Because so many maneuvers took place behind the scenes and unfolded slowly, digital cinema seemed very distant to me. To understand the whole process, I had to do some research. Only in hindsight did the quiet buildups and sudden jolts form a pattern.

On the production end, it seems likely that filmmakers will continue to migrate to digital formats at a moderate pace. Proponents of 35mm are fond of pointing out that six of 2012’s Oscar-nominated pictures were shot wholly or partly on film. (To which you might well respond, Who cares about Oscar nominations? I would agree with you.) Yet even 35mm adherent Wally Pfister, DP for Christopher Nolan, admits that within ten years he will probably be shooting digital.

What about the other wings of the film industry, distribution and exhibition? Put aside distribution for a moment. Digital exhibition was the central focus of the blog series that became my e-book Pandora’s Digital Box. There I try to trace the historical process that led up to the big changes of 2009-early 2012.

Today, a year after Pandora’s publication, everybody knows that 35mm exhibition of recent releases is almost completely finished. But let’s explore things in a little more detail, including poking at some nuts and bolts. As we go, I’ll link to the original blog entries.

Top of the world!

35mm print of Warm Bodies about to be shipped out from Market Square Cinemas, Madison, Wisconsin; 10 May 2013.

The overall situation couldn’t be plainer. At the end of 2012, reports David Hancock of IHS Screen Digest, there were nearly 130,000 screens in the world. Of these, over two-thirds were digital, and a little over half of those were 3D-capable.

Northern European countries have committed heavily to the new format. The Netherlands, Denmark, and Norway are fully digital, while the UK is at 93% saturation and France is at 92%. Both national and EU funds have helped fund the switchover. Hancock reports that in Asia, Japanese screens are 88% digital, and South Korean ones are 100%. China is the growth engine. Rising living standards and swelling attendance have triggered a building frenzy. Over 85%, or 21,407 screens are already digital, and on average, each day adds at least eight new screens.

In the US and Canada, there were at end 2012 still over 6400 commercial analog screens, or about 15% of the nearly 43,000 total. My home town, Madison, Wisconsin, has a surprising number of these anachronisms. One multiplex retains at least two first-run 35mm screens. Five second-run screens at our Market Square multiplex have no digital equipment. That venue ran excellent 2D prints of Life of Pi (held over for seven weeks) and The Hobbit: An Unexpected Journey. It’s currently screening many recent releases, including the incessantly and mysteriously popular Argo. In addition, our campus has several active 35mm venues (Cinematheque, Chazen Museum, Marquee). Our department shows a fair amount of 35mm for our courses as well; the last screening I dropped in on was The Quiet Man in the very nice UCLA restoration.

Unquestionably, however, 35mm is doomed as a commercial format. Formerly, a tentpole release might have required 3000-5000 film prints; now a few hundred are shipped. Our Market Square house sometimes gets prints bearing single-digit ID numbers. Jack Foley of Focus Features estimates that only about 5 % of the copies of a wide US release will be in 35mm. A narrower release might go somewhat higher, since art houses have been slower to transition to digital. Focus Features’ The Place Beyond the Pines was released on 1442 screens, only 105 (7%) of which employed 35mm.

In light of the rapid takeup of digital projection, Foley expects that most studios will stop supplying 35mm copies by the end of this year. David Hancock has suggested that by the end of 2015, there won’t be any new theatrical releases on 35mm.

Correspondingly, projectionists are vanishing. In Madison, Hal Theisen, my guide to digital operation in Chapter 4 of Pandora, has been dismissed. The films in that theatre are now set up by an assistant manager. Hal was the last full-time projectionist in town.

The wholesale conversion was initiated by the studios under the aegis of their Digital Cinema Initiatives corporation (DCI). The plan was helped along, after some negotiation, by the National Association of Theatre Owners. Smaller theatre chains and independent owners had to go along or risk closing down eventually. The Majors pursued the changeover aggressively, combining a stick—go digital or die!—with several carrots: lower shipping costs, higher ticket prices for 3D shows, no need for expensive unionized projectionists, and the prospect of “alternative content.”

The conversion to DCI standards was costly, running up to $100,000 per screen. Many exhibitors took advantage of the Virtual Print Fee, a subsidy from the distributors that paid into a third-party account every time the venue booked a film from the Majors. There were strings attached to the VPF. The deals are still protected by nondisclosure agreements, but terms have included demands that exhibitors remove all 35mm machines from the venue, show a certain number of the Majors’ films, equip some houses for 3D, and/or sign up for Network Operations Centers that would monitor the shows.

The biggest North American chains are Regal, AMC, and Cinemark. They control about 16,500 screens and own fifty-three of the sixty top-grossing US venues. The Big Three benefited considerably from the conversion. By forming the consortium Digital Cinema Solutions, they were able to negotiate Wall Street financing for their chains’ digital upgrade. They also formed National Cinemedia, a company that supplied FirstLook, a preshow assembly of promos for TV shows and music. Under the new name of NCM Network, the parent company now links 19,000 screens for advertising purposes. NCM also supplies alternative content to over 700 screens under the Fathom brand: sports, musical acts, the Metropolitan Opera, London’s National Theatre, and other items that try to perk up multiplex business in the middle of the week.

The digital conversion has coincided with—some would say, led to—a greater consolidation of US theatre chains. Last year the Texas-based Rave circuit was dissolved, and 483 of its screens, all digital, were picked up by Cinemark. More recently, the Regal chain gained over 500 screens by acquiring Hollywood Theatres. The biggest move took place in May 2012 when the AMC circuit was bought for $2.6 billion by Dalian Wanda Group, a Chinese real estate firm. Combined with Wanda’s 750 mainland screens, this acquisition created what may be the biggest cinema chain in the world. Wanda has declared its intent to invest half a billion dollars in upgrading AMC houses.

Meanwhile, vertical integration is emerging. In 2011, Regal and AMC founded Open Road Films, a distribution company. It has handled such high-profile titles as The Grey, Killer Elite, End of Watch, Side Effects, and The Host. Cinedigm, which began life as a third-party aggregator to handle VPFs, has moved into distribution too, billing itself as a company merging theatrical and home release strategies tailored to each project.

It has become evident that the digital revolution in exhibition permits American studio cinema a new level of conquest and control. Distribution, we’ve long known, is the seat of power in nearly all types of cinema. Whatever the virtues of YouTube, Vimeo, and other personal-movie exhibition platforms, film’s long-standing public dimension, the gathering of people who surrender their attention to a shared experience in real time, is still largely governed by what Hollywood studios put into their pipeline.

On the margins and off-center

View of Madagascar from the Sky-Vu Drive-In, 2012. Photo by Duke Goetz.

While the Big Three grew stronger, what became of smaller fry? John Fithian of NATO suggested that any cinema with fewer than ten screens could probably not afford the changeover, and David Hancock suggested that up to 2000 screens might be lost. Recent speculation is that drive-ins will be especially hard hit. Pandora’s Digital Box, as blog and then book, surveyed those most at risk: the small local cinemas and the art houses.

I fretted about the loss of small-town theatres, not least because I grew up with them. Data on such local venues are hard to get, so for the blog and the book I went reportorial and visited two Midwestern towns. The blogs related to them are here and here.

The long-lived Goetz theatres in Monroe, Wisconsin, consist of a downtown triplex and the Sky-Vu drive-in. They’re run by Robert “Duke” Goetz, whose grandfather built the movie house back in 1931. Duke is a confirmed techie and showman. He designs and cuts ads and music videos to fill out his show, and he personally converted all his screens to 7.1 sound. So it’s no surprise that he’s a fan of digital cinema. But back in December his digital upgrade took place during the worst box-office weekend since 2008–a bad omen, if you believe in omens.

Seventeen months later, Duke reports more cheerful news. Everything has gone according to plan and budget. The company that installed the equipment, Bright Star Systems of Minneapolis, has proven reliable and excellent in answering questions. Duke especially likes the fact that digital projection allows him to “play musical chairs with the click of a mouse.”

I can move movies from screen to screen in short order or download from the Theatre Management System to any and all theatres at one time, so when the weather is damn cold, for Monday -Thursday screening I’ll play the shorter movies in the biggest house. . . . I am now able to start the movies from the box office with software that accesses the TMS, so it’s just like being at the projector. It saves my guys time and keeps them where the action is.

Duke programs his offerings to suit the tastes of the town, and for the most part, he can get the films he wants. Attendance at the three-screener has increased, partly, he thinks, because of digital. Even marginal product gets a bit more attention when people find the image appealing. Duke says that Skyfall played so long and robustly partly because it was a strong movie, but also because the presentation was compelling. Thanks to his subwoofer, viewers could feel onscreen shotgun blasts in their backsides. Immersion goes only so far, however. Duke remains leery of 3D: “People are tired of paying the extra charge, and with the economy in my area I’ll still wait.”

Contrary to trends elsewhere, the Sky-Vu has benefited strongly from digital display. Duke’s was the first North American drive-in to sign up for the NEC digital system. People comment on how the bright, sharp image has improved their experience. The drive-in had “a tremendous summer,” with the first Saturday night of Brave, coupled with Avengers, proving to be the best night of the year. Measured by both box office returns and number of admissions, that show did better than Transformers the summer before. Last fall, when the Sky-Vu was the only area drive-in still open, some patrons traveled 2 1/2 hours from Illinois. The only problem with digital under the stars was that Duke couldn’t get a satisfactory VPF deal for an outdoor cinema because he doesn’t run it year-round.

While Duke runs the Goetz theatres as a family business, the JEM Theatre in Harmony, Minnesota is more of a sideline for its owner-operator Michelle Haugerud. A single screen running only at 7:30 on weekend nights, the JEM plays a unifying role in the life of the town. But it’s a small market. Harmony consists of only 1020 people (many of them Amish), and the median household income is about $30,000. Michelle had to finance the conversion through donations and bank assistance. The task was complicated by the unexpected death of her husband Paul, who ran the JEM with her.

Michelle reports that the digital conversion hasn’t increased business. Box office was about the same in 2012 as in 2011, and so far this year ticket sales have been down. It has been a slow winter and spring throughout the industry, and people are hoping the summer blockbusters will lift revenues. But the JEM faces particular problems that the Goetz doesn’t.

Michelle wants to show films in first run, as Duke does. But the distributors typically demand that she play a new movie for three weeks. That’s not feasible in her small town, so Michelle winds up missing out on films she knows would draw well. In addition, she’d be willing to screen two shows a day, the first a kid movie and the second an adult picture, but the companies don’t allow this double-billing. Moreover, she thinks that the shrinking windows–the speed with which films come out on Pay Per View, VOD, and DVD–are eroding her audience. “Many people are willing to wait for these releases since they now realize they will be out shortly after they hit the theatres anyway.”

Michelle and her family run the JEM as much for the community as for themselves. She is hoping for better times.

Converting to digital has made showing movies easier, and I have had no issues with the new equipment. However, it has not helped with ticket sales at all. I am holding on and committed to this year, but if I get to the point where it is costing me personally to stay open, I don’t think I will continue. I love having the movie theatre and would love to keep it going. I do feel if I had a say on what movies I showed and when, I would do so much better.

Kickstarting the arthouse

Robert Redford addresses the Art House Convergence, January 2013.

Several managers and programmers of arthouse cinemas around the country have formed an informal association, the Art House Convergence. It meets once a year just before the Sundance Film Festival, which many members attend. When I visited the conference in 2012, the digital transition was the central topic. It aroused curiosity, bewilderment, frustration, and some annoyance. This year, things were different.

Participants were calmly reconciled to the inevitable, and some looked forward to it. On one of the few panels that took up the subject, moderator Jan Klingelhofer of Pacific Film Resources began by asking: “How many of you are still on the fence about digital?” Just one hand was raised.

On the panel, technology experts from major companies showed how new projection systems could be installed even in offbeat venues. The New Parkway in Oakland was once a garage, and the Mary D. Fisher Theatre in Sedona is a converted bank. Panelists also gave information on choices of technology, from lamps and servers to the best screen materials for 3D. The teeth-gnashing is over, and now art-house leaders are focusing on practicalities: the best strategies suited for their business models.

A private, for-profit art house faces many of the problems faced by Duke Goetz and Michelle Haugerud, except that the art-house is screening films of narrower appeal. Because the audience is smaller and more select, many art houses have become not-for-profit entities created by community cultural organizations. They are dependent on donations, private or public patronage, and miscellaneous income from many activities, not only screenings but filmmaking classes, special events, and other activities. A good example of the diversity of outreach an arthouse can have is the Bryn Mawr Film Institute, whose director, the estimable Juliet Goodfriend, also coordinates the annual AHC survey. So the coordinators of the not-for-profit theatre must persuade boards of directors and generous patrons that the digital upgrade is necessary.

Small venues, whether private or not-for-profit, can’t benefit much from economies of scale. A multiplex can amortize its costs across many screens, but a big proportion of art houses boasts only one or two. Add to this the fact that multiplexes are encroaching on the art-house turf with crossover films like Moonrise Kingdom and upscale entertainment like opera and plays from Fathom. Even museums are starting to install digital equipment and play arts-related programming.

The chief task, of course, is paying for the upgrade. Last year’s AHC session was often about the money. Small local cinemas like the Goetz could benefit from VPF deals, but for many art houses such deals weren’t a good option. These houses don’t run enough films from the Majors to repay the subsidy. While they’re often eager to take something from Fox Searchlight, Focus Features, and the Weinstein company, they book a lot from IFC, Magnolia, and other independent distributors.

A common solution was to launch fundraising campaigns from the community, much as Michelle did in Harmony. One of the biggest initiatives was that conducted by the boundlessly energetic John Toner and Chris Collier of Renew Theaters in Pennsylvania. Without going for a VPF, they raised $367,000 to pay for converting three screens (one in 3D). John and Chris are vigorous advocates for the new format, and their “This Is Digital Cinema” series treats restorations of classics like Gilda and The Ten Commandments as showcases for the DCP. At AHC 2013, John and Chris provided an entertaining PowerPoint presentation on how they managed the switchover; for a prose version, you can read John’s account here.

Likewise, the Tampa Theatre raised $89,000 from its community. But what if your community can’t sustain such a big campaign? I hadn’t predicted in Pandora how powerful Kickstarter would be in the film domain, and the results are initially encouraging. Donations to the Cable Car Cinema and Cafe of Providence surpassed the goal by six thousand dollars, and the theatre is already preparing for the new equipment. The final 35mm program will be, what else?, The Last Picture Show, complete with pulled-pork sandwiches. The Crescent Theatre of Mobile won nine thousand more than it asked for, and Martin McCaffrey, venerable moving spirit of Montgomery’s Capri Theatre, followed suit and came out ahead by about the same amount.

Currently the Kickstarter site lists dozens of conversion projects, and many have met their goals–with Boston’s Brattle and LA’s Cinefamily hitting over a hundred thousand dollars. The pitches are pretty creative (“The Cinefamily is a non-profit movie theater with awesome programming, but crappy everything else”) and so are the giveaways (the Skyline drive-in of Everett, Washington offers a vintage speaker box that’s “clean and suitable for presentation”).

So maybe predictions were too pessimistic. Will we lose so many theatres to the switchover? Maybe not. But raising money for the initial conversion isn’t the whole story.

Technology: Running in place to keep up?

In the shift to digital projection, some would say the pivotal moment came with the success of Avatar and other 2009 3D releases (Monsters vs. Aliens, Ice Age: Dawn of the Dinosaurs, and Up). In 2009 there were about 7400 digital screens; a year later there were nearly 15,000. Then the acceleration began. Ten thousand screens converted in 2011 and eight thousand more the following year.

But I see 2005 as another major marker. In 2004, there were only 80 digital screens in the US. By the end of 2005, there were over 1500. The early adopters were pushed by the emergence of 3D, heavily touted by several major directors at NATO’s annual convention and the strong 3D releases of The Polar Express (2004) and Chicken Little (2005). So there were two bursts of digital adoption, both driven by 3D.

With 3D as a Trojan horse, digital entered exhibition. The format eventually settled on was the Digital Cinema Package, an ensemble of files gathered on a hard drive. The movie, with subtitles and alternate soundtracks, is wrapped in a thick swath of security files. The studios, petrified of piracy, had delayed the completion of digital cinema for some years until an ironclad system was protecting the movie. The DCP can be opened only with a customized key, delivered to the theatre separately from the hard drive. Typically the key is sent on a flash drive, so that the staff member need not retype the tediously long string of alphanumeric characters that make it up. Copying that key into the theatre’s server, its theatre management system, or the projector’s media block allows the film to be played on a certified projector.

A digital projector suitable for multiplex use relies on one of two available technologies. Sony’s proprietary system works only on its own projectors. Texas Instruments’ Digital Light Processing (DLP) technology was licensed to three manufacturers: Christie, Barco, and NEC. By fall 2010, all four companies had produced high-level, and quite expensive, machines capable of producing 4K displays. The rush to convert led to thousands of units being bought over a few months. This was great for business in the short term, but how could the manufacturers count on selling the product in the years and decades ahead? Michael Karagosian sketches the problem: “The big challenge today for technology companies is the massive downturn in sales that is destined to take place the last half of this decade as the digital installation boom ends.”

One way to expand the market was offered by cheaper machines. In fall of 2012, all the manufacturers introduced DCI-compliant projectors suitable for screens around thirty feet wide. The machines were still quite expensive, but they were marginally more affordable for the smaller or independent exhibitors who had been reluctant to convert or who had missed the deadlines for VPF financing. To maintain a quality difference from high-end machines, the cheaper versions typically lacked some features. They might be capable of only 2K, or they might not permit a wide range of frame rates, or they offered less brilliant illumination.

Another answer to a saturated market was continuous research and development. No sooner had exhibitors installed the “Series 2” projectors introduced in late 2009-early 2010 than speculation began about enhancements. How soon, for instance, might we expect 6K or even 8K resolution? Two other innovations were responding to problems with the dimness of digital 3D images.

One possibility was laser projection, which would be expected to brighten the image considerably. Laser projectors may start appearing in Imax cinemas later this year, but for most venues the current costs are prohibitive, running about half a million dollars per installation.

3D light levels could also be boosted by shooting and showing at higher frame rates than the standard 24. Peter Jackson famously experimented with 48-frame production on The Hobbit: An Unexpected Journey, and some theatres screened it that way. Response was mostly skeptical, with critics complaining of the hypersharp, “soap-opera” effect onscreen. The frame-rate issue has mostly quieted down, but it did trigger academic studies of the perceptual psychology involved in frame rates. In addition, James Cameron has insisted that his sequels to Avatar will be shot at an even higher frame rate. Most projectors require new software in order to increase frame rates.

Alongside developments in the projection market have come new devices for sound. As Jeff Smith pointed out in an earlier entry, innovative sound systems have been enabled by the switchover to digital presentation. 35mm film stock constrained the amount of physical space on the film strip that auditory information could occupy. Now that sound is a matter of digital files, sound designers can add many tracks for greater immersive effects—so-called “3D audio” platforms. Barco’s Auro 11.1 system and Dolby Atmos position several more speakers around the auditorium, including ones high above the audience. Costs of installation for these systems run from $40,000 to $90,000.

Still, projector and sound-system manufacturers can assume that business will continue because of the pressures for change inherent in digital technology. Experienced equipment installers suggest that a digital projector’s life is between five and ten years. Already the Series 1 projectors introduced in 2005 are becoming obsolete. Chapin Cutler, of Boston Light & Sound, notes:

A digital projector is a computer that puts out light. How many computers will you go through in the next ten years?

How many Series 1 projectors are still in use and supported by the manufacturers? Try buying parts for them. I know of one that was purchased four years ago that has been pushed into a corner. It has sat there for about two months so far, with no end in sight. (Thank heavens they still have their 35 mm gear!) It is broken and the manufacturer cannot supply parts; their customer service department doesn’t know about the machines, as they have only had to deal with the newer models; and the parts are not listed in their own internal parts book. Yes, four years old.

When replacement parts are available, they can be exceptionally pricey. A projector’s light engine, central to the image display, can run $22,000. And if an exhibitor buys a brand-new projector some years from now, the studios aren’t likely to launch a new round of VPF financing.

So even if a theatre can afford the expense of conversion today, upgrades and maintenance will demand big commitments of money in the years ahead. John Vanco, Senior VP and manager of New York City’s IFC Center, has put it well:

Many, many small, independent theatres, which are vital to the survival of non-studio films, will end up being fatally hobbled by the transition. They may be able to raise funds to cover the initial conversion, but what will crush many of them in the long term is the ongoing capital resources that will be necessary to continue to have DCI-compliant equipment in the next ten and twenty years. . . .

In the same way the current inexorable pattern of planned obsolescence forces consumers to continually repurchase computers, phones, etc., cinemas too are going to find that they have to spend much more for cinema equipment over the next twenty years than they did, say, from 1980 to 2000. . . . So these technological progressions will make it harder for those small theatres to survive.

Dylan Skolnick of Huntington, New York’s Cinema Arts Centre adds to Vanco’s point. “We have great supporters, but I can’t go back to them every five-to-ten years with a ‘Digital Upgrade or Die’ campaign.”

The problem is acute for small and art-house venues, but it isn’t minor for the Big Three either. Unless film attendance jumps spectacularly (it has been more or less flat for several years), exhibitors may need to raise ticket prices and the costs of concessions. This strategy may work in urban areas but won’t be popular elsewhere. Moreover, part of the boom in box-office revenues during recent years has been due to the upcharge for 3D features. But in the US, 3D revenues are currently leveling off at about $1.8 billion, a drop from the format’s 2010 peak of $2.14 billion. In 2012, 3D’s market share slipped as well. It isn’t clear that people would flock to 3D if the images were brighter. And if 3D television takes off, stereoscopic cinema will seem less compelling as a novelty.

Some observers hold out hope for glasses-free 3D technology in theatres, a change that would probably boost business. But the difficulties of creating 3D of this sort for multiplex venues are immense. The glasses-free platforms proposed by Dolby are aimed at small displays, like TVs, smartphones, and tablets. Of course, if 3D without glasses were devised for big screens, it would almost certainly demand yet another projector redesign.

No more silver bricks

When it comes to distribution, digital isn’t there yet. The UPS and Fed Ex corps still bring movies to multiplexes the old-fashioned way. The little briefcases are a lot lighter than hulking metal shipping cases, but we’re still dealing with physical artifacts.

At least for the moment. Festival submissions are already being placed in Cloud-based lockers like Withoutabox in an effort to replace DVD screeners. Online delivery is already being used for many of those operas, ballets, and other forms of “alternative content” flowing onto screens from various suppliers. A Norwegian distributor sent a 100 gigabyte local film, fully encrypted, to forty cinemas in the spring of 2012. This and experiments in other countries employ fiber-based networks, but the Digital Cinema Distribution Coalition, a joint venture among Hollywood studios and the Big Three exhibition chains, is exploring satellite systems.

So much for the impassive silver bricks in their cute pink beds on the cover of Pandora’s Digital Box. They may become as quaint as film reels and changeover cue-marks. For a time, the hard drives may survive as backup systems that will reassure exhibitors, but eventually no physical site may serve as the movie’s home. An exhibitor will download the film to the server, apply a decryption key sensitive to time, venue, and machine, and the movie will be, as they say, “ingested.”

In the Pandora book, I included chapters on other exhibition domains I haven’t revisited here. Take archives. More and more studios refuse to rent prints, will not prepare DCPs of most classic titles, and won’t let theatres screen Blu-ray discs commercially. So repertory cinemas turn to archives, seeking to rent 35mm copies that may be irreplaceable. In addition, archivists, laboring under tight budget constraints, are racing to preserve and restore their material on film, which remains the most stable support medium. At the same time, archives are expected to get involved in preparing high-quality digital versions of popular classics. Henceforth most restorations that you see will be circulated on 2K or 4K, as Metropolis, La Grande Illusion, and Les Enfants du Paradis have been in recent years.

Film festivals, as Mike King, one of our Wisconsin Film Festival programmers observes, are now file festivals. Cameron Bailey reported that of the 362 titles screened at TIFF last year, only fifty-one were on film. Last month, our annual event ran twenty-one new films on film; most were 16mm experimental items. The remaining 132 were on DCP, HDCam, Quicktime files, or DVD/Blu-ray. On the plus side, independent filmmakers are learning to encode their films in the DCI-compliant format, often without layers of security, so at least in this respect technology may not be a severe barrier to entry.

As for me, I’m still in the midst of churn. I watch movies on film, on DCP, on DVD and Blu-ray and VOD, even on laserdisc, and sometimes on my iPad. But my research will miss 16mm and 35mm. Some of the questions I like to ask can be answered only by handling film. Last weekend I sat down at a Steenbeck flatbed and counted frames in passages of Notorious and King Hu’s Dragon Inn. This sort of scrutiny is virtually impossible on DVDs and Blu-rays, which don’t preserve original film frames.

What I’ve lost as a specialist is offset by many gains. Since the arrival of Betamax and VHS, nontheatrical cinema has expanded to limits we couldn’t have imagined in the 1970s. Thanks to consumer digital formats, more people have more access to more movies of all sorts than at any point in history. Although some aspects of film-originated movies are hard to recover on digital playback, we can study cinema craft to an extent that wasn’t possible before. Digitization has allowed sophisticated visual and sonic analysis to bloom on websites around the world. See, among many examples, Jim Emerson’s Scanners and A. D. Jameson’s work on Big Other.

With the rise of nontheatrical consumption, though, what’s most at risk is theatrical cinema: film viewing as a public forum. Exhibition outside film festivals is already starting to narrow to recent releases and a few approved classics. We will be able to watch The Suspended Step of the Stork and Leviathan on our home screens for a long time to come, but very seldom on the scale that benefits them most.

As ever, the problem of technology isn’t only a matter of hardware. Technology develops within institutions. Hollywood has standardized a new technology favoring its goals. The institutions of minority film culture–festivals, art houses, archives, local cinemas, schools–need to be robust and resourceful to maintain all the types of cinema we have known, and the types we might yet discover.

Since Pandora was published, a very comprehensive guide to the mechanics of digital projection has appeared: Torkell Saætervadet’s FIAF Digital Projection Guide, and it’s a must. One rich treatise I didn’t cite in Pandora is Hans Keining’s 2008 report 4K+ Systems: Theory Basics for Motion Picture Imaging. Michael Karagosian’s website is an excellent general source on digital exhibition in the late 2000s.

Screen Daily provides a good overview of the new technology on display at CinemaCon 2013. For general background on industry trends after the changeover, see the Variety article “Filmmakers Lament Extinction of Film Prints.” As for archives, Nicola Mazzanti edited a very useful European Commission study, Challenges of the Digital Era for Film Heritage Institutions (Berlin/ UK, 2012). May Haduong surveys current problems of print access and film archives in “Out of Print: The Changing Landscape of Print Accessibility for Repertory Programming,” The Moving Image (Fall 2012), 148-161. The piece requires online library access, but a summary is here.

Much of the industry information in this entry came from proprietary reports published in IHS Screen Digest. Thanks to David Hancock for his assistance with other data, and to Patrick Corcoran of NATO for updated information on theatre conversion. Thanks as well to Chapin Cutler, Duke Goetz, Michelle Haugerud, and Dylan Skolnick for permission to quote them. I’m also grateful to Jack Foley of Focus Features and Joshua Hittesdorf of Market Square Cinemas. Finally, I want to thank Russ Collins and his colleagues at the Art House Convergence for mounting another splendid event and for inviting me back last January. I continue to learn from the discussions on the AHC listserv, and I’m particularly grateful to John Toner for his reports on independent cinemas’ funding efforts.

Other entries on this site offer material on the digital transition. There’s “It’s good to be the King of the World,” on James Cameron’s push for 3D TV; “ADD = Analog, digital, dreaming,” about the powers of photochemical cinema on display at the Toronto International Film Festival 2012; “Digital projection, there and here,” some notes on the situation in Western Europe; and “Side by side: Quick catchups,” includes notes on sources for studying digital cinema. In “16, still super,” veteran programmers talk about how they continue to rely on this format; in the process they convey their commitment to providing unusual fare.

P. S. 15 May 2013: Rebecca Hall of the extraordinary Northwest Chicago Film Society has posted a continually updated list of theatres that are dedicated to showing films in 16mm and 35mm.

P.P.S. 12 June: David Hancock has just presented a very full report entitled “Digital Cinema Worldwide: 35mm phased out in many countries, though some lag behind.” It is published in the June IHS Screen Digest. One of my remarks above has been corrected in light of some information in the report: I claimed that Belgium has fully converted, but David’s figures indicate 96.5% conversion.

David predicts that by end 2013, 90 % of world screens will be digital. Even India is making the move, as circuits relying on DVD or other low-resolution sources are converting to DCI-compatible equipment. Those regions slowest to convert include Italy, Greece, and Spain (not surprisingly, given recent austerity policies), as well as areas of South America and the Pacific (e.g., Thailand, the Philippines). Thanks to David and his team at IHS Screen Digest for their comprehensive coverage of this process.

Dragon Inn (King Hu, 1967). 35mm frame enlargement, taken on Fujichrome 64.