Albatros soars

Tuesday | May 21, 2013 open printable version

open printable version

Gribiche (1925).

Kristin here:

Lazare Meerson was one of the great set designers of the late silent period and into the 1930s. His name may not immediately ring a bell, but he designed the great French films of René Clair (La Proie du vent, An Italian Straw Hat, Les deux timides, Sous les toits de Paris, Le Million, À nous la liberté, and La Quatorze Juilliet) and Jacques Feyder (Gribiche [above], Carmen, Les Nouveaux Messieurs, Le Grand Jeu, Pensions Mimosas, and La Kermesse héroïque). He crossed paths with most of the major French Impressionist directors, sometimes in their post-Impressionist periods: Marcel L’Herbier (Feu Mathias Pascal, his masterpiece L’Argent, Le Mystère de la chambre jaune, and Le parfum de la dame en soi), Jean Epstein ( Les Aventures de Robert Macaire), and Abel Gance (Le fin du monde and Poliche). His credits include work with such French directors as Maurice Tourneur, Julien Duvivier, and Claude Autant-Lara.

Meerson was born in Russia and fled the Revolution. Making his way via Germany to Paris, he became the assistant to set designer Alberto Cavalcanti on Feu Mathias Pascal. That’s one of the five French films on a new Flicker Alley release, “From Moscow to Montreuil: The Russian Émigrés in Paris: 1920-1929.” Meerson’s illustrious career led him to England in the second half of the 1930s, where he designed several notable films, including Paul Czinner’s As You Like It, Clair’s Break the News, and Feyder’s Knight without Armour, as well as the classic The Scarlet Pimpernel. He died in 1938 at the young age of 38. (The best online source on Meerson is R. F. Cousins’ filmography, bibliography, and brief biography.) His influence lives on in the work of his most prominent student, Alexandre Trauner (Le jour se lève, among many others).

I begin with Meerson in order to stress how many important strands of film history come together in this very ambitious Flicker Alley set. It allows us to trace Meerson’s early years, from his first apprentice work, Feu Mathias Pascal, to his first and third projects for Feyder. That in itself would be enough to make this release notable, but the Albatros film studio in Paris during the 1920s hosted an amazing collection of talented people working in the cutting-edge styles of the era.

Here we also find three films starring the extraordinary Russian star Ivan Mosjoukine, known to most audiences by reputation only, and then only for the ephemeral Kuleshov experiment that used footage from an old film with Mosjoukine.  This experiment is not known to survive. In it a close view his impassive face reputedly was edited together with shots of a dead woman, a bowl of soup, a small child, or perhaps other subjects, depending on which report you read. Spectators supposedly credited Mosjoukine with a marvelous performance, based on eyeline editing rather than any changes in his expression. We shall probably never know the exact form this experiment took and who saw it. I have to believe that the shots of Mosjoukine were inserted at wide intervals in a feature film, not strung together one right after the other, as makers of modern “reconstructions” of the experiment seem to assume. It’s much more interesting to watch Mosjoukine in the three very different performances presented here: Le Brasier Ardent, Kean, and Feu Mathias Pascal. His face is anything but impassive

This experiment is not known to survive. In it a close view his impassive face reputedly was edited together with shots of a dead woman, a bowl of soup, a small child, or perhaps other subjects, depending on which report you read. Spectators supposedly credited Mosjoukine with a marvelous performance, based on eyeline editing rather than any changes in his expression. We shall probably never know the exact form this experiment took and who saw it. I have to believe that the shots of Mosjoukine were inserted at wide intervals in a feature film, not strung together one right after the other, as makers of modern “reconstructions” of the experiment seem to assume. It’s much more interesting to watch Mosjoukine in the three very different performances presented here: Le Brasier Ardent, Kean, and Feu Mathias Pascal. His face is anything but impassive

We can also appreciate Belgian-born director Jacques Feyder, who had begun his feature-film career with L’Atlantide (1921) and Crainquebille (on our 10-best list for 1922) and then suffered a box-office disappointment with the charming, poignant Visages d’enfants, making two notable films for Albatros. Gribiche contains the first performance by Françoise Rosay, Feyder’s wife, who became one of the grandes dames of French cinema.

Most of all, however, this set makes a big step in showing us what happened after the Revolution to the most important Russian production company, that of Josef Ermolieff. The founder, as Lenny Borger points out in the highly informative booklet accompanying the set, had French connections from the start. Ermolieff “begin his career as a technical assistant at Pathé’s Moscow branch, and by 1912 had moved up through the ranks to become Pathé’s sales agent in Russia. On the verge of the war, he founded his own company and studio and gathered around him a core of artists and technicians who later would become the Russian film colony of Paris.”

The Russian work of the Ermolieff company was revealed to modern audiences in the groundbreaking retrospective of pre-Revolutionary Russian cinema presented at the La Giornate del Cinema Muto festival in Pordenone, Italy in 1989. The flood of hitherto unknown films included great melodramas starring Mosjoukine and other wonderful actors who made their way to Paris in the wake of the Revolution.

Ermolieff initially took his company to Yalta, where in 1918-19, they made several films. The next stop was Constantinople, and finally Paris via Marseilles. Ermolieff purchased the old Pathé studio in Montreuil-sous-Bois and set up filmmaking. The first film entirely produced there, Yakob Protazanov’s L’Angoissante aventure (1920) is not included in the Flicker Alley set. It does survive, however. I remember it as an entertaining film with the added attraction of having a story built around filmmaking. Perhaps someday that, too, can be made available on DVD. In the meantime, the five films in the set show the Russian emigrés gradually merging with the French filmmaking establishment of the day and supporting the work of some of the important Impressionist filmmakers.

Ermolieff himself decided to set up shop in Germany, selling the studio to two of his colleagues, Alexandre Kamenka and Noë Bloch. Renaming the firm Les Film Albatros, they brought it into the mainstream of French cinema.

Le brasier ardent (1923)

Mosjoukine directed two films, of which this is the second. It has a reputation as an audacious, surrealist, and almost incomprehensible film. This may be due to the fact that prints available in archives during the 1970s and 1980s lacked intertitles. The opening nightmare sequence is indeed disturbing, but at least with intertitles, we understand that it is only a dream. It begins with a wild-eyed man tied to a stake where he is about to be burned. The heroine stands looking on, resisting as the man pulls on her long hair, apparently intent on dragging her into the fatal flames to accompany him in death. Subsequent scenes of the nightmare show the heroine encountering different men, all played by Mosjoukine, culminating in a man in evening dress stalking her along a vaguely Expressionist street until she escapes and wakes up in bed.

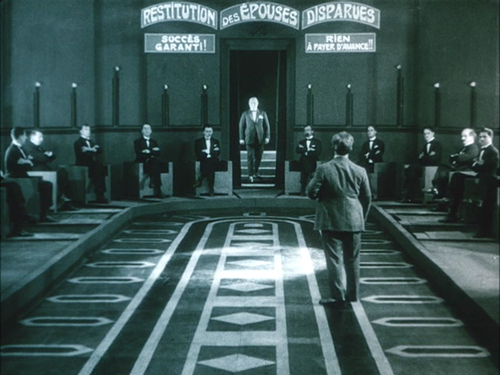

This nightmarish opening must have established vivid expectations in the spectators of 1923 as to what sort of film they were in for. After the heroine wakes up, however, what follows is quite different. The main plot is a stylized but quite amusing comedy. The heroine is a pampered wife, married to a rich man whom she does not love. She is faithful, but he is unreasonably jealous. He goes to a distinctly odd detective agency, one department of which is “Recovery of Lost Wives” (above), with “Success guaranteed!” and “Nothing to pay in advance!” Juxtaposed with the bizarre opening, this quirky humor might have eluded puzzled audiences of the day. Certainly the film itself was a failure, and Mosjoukine stuck to acting thereafter.

Unfortunately for the husband, Detective Z, whom he picks from the eccentric group pictured above, is the very man, again played by Mosjoukine, whom his wife has dreamed about. What follows is an odd tale with the detective and wife gradually falling love. Mosjoukine, known for his tragic, intense characters in the Russian cinema, plays such figures in the fantasy sequences–but in the main story he is allowed to play for laughs, gamboling and rolling on the floor like a puppy when the wife finally appears at his mother’s apartment and declares her love for him.

Mosjoukine should not, however, be allowed to overshadow his co-stars, Ermolieff actors who were also were to make their way into the wider French production of the day, including Impressionism. The wife is played by Nathalie Lissenko, one of the stars of the pre-Revolutionary cinema, who had acted opposite Mosjoukine in Russia. Among her 1920s roles was the protagonist of one of Epstein’s finest films, the largely unknown L’Affiche (1924). The husband is Nicolas Koline, who started his career with Ermolieff only after the company had left the Soviet Union. He will be familiar to silent-film fans from his performance as Tristan Fleury in Gance’s Napoléon.

Kean (1923)

Le Brasier ardent has definite touches of the Impressionist style, but Alexandre Volkoff’s big-budget biopic Kean went further in that direction. I have to admit that it’s not one of my favorite Albatros films. Borger points out that, although it was a prestige picture in its day and quite successful, it has not worn well. The fault in part may lay in the source material, a play co-authored by Alexandre Dumas. Still, the film is notable for Mosjoukine’s anguished performance as the great Shakespearean actor. It also contains one of the most famous sequences of the Impressionist movement, where Kean gets drunk and dances frantically. Borger describes it: “The increasingly frenzied cutting that translate his state of mind was not there by chance: since the trade screenings of Abel Gance’s La Roue [also released by Flicker Alley] a few months prior to the shooting of Kean, rapid-cutting had become all the rage in French films–look at some of the major commercial pictures produced after La Roue’s release and you will find at least one obligatory explosion of rapid editing. But Volkoff was Gance’s best imitator.”

Feu Mathias Pascal (1925)

To quote myself from an article in the issue of Griffithiana devoted to the 1989 Pordenone retrospective:

These two films abruptly brought the Albatros group to the attention of the Impressionist directors and to supporters of the French avant-garde cinema. After having virtually ignored the Russian emigrés to this date, Cinéa published a long article on Le Brasier ardent and an interview with Mosjoukine; Kean received similar attention, and articles in Cinéa-Ciné pour tous and Cinémagazine appeared reguarly thereafter. After this point, Mosjoukine starred in films by the French Impressionists as well as those by emigré directors: Le Lion des Mogols, for Epstein, Feu Mathias Pascal, for L’Herbier, and, nearly, in Napoléon, for Gance.

For decades Feu Mathias Pascal was the most familiar of L’Herbier’s films, at least in the USA, where an abridged version was part of the Museum of Modern Art’s circulating 16mm collection. By now his L’Argent (1928) has probably eclipsed the earlier film’s reputation, at least in the eyes of critics, historians, and silent-film enthusiasts. Feu Mathias Pascal is a more approachable film, though, and would be a good choice for teaching French Impressionism.

Adapted from a novel by Pirandello, it stars Mosjoukine as a character described at the outset: “From childhood Mathias Pascal, a tormented dreamer, has cherished a fantastic hope to free himself to become his own Master!” This paves the way for the many dreams, visions, and heightened emotional states that will be conveyed by the superimpositions, selective focus, camera movements, and fast cutting beloved of the Impressionists.

Pascal finds himself in exactly the sort of situation he hates: tormented by his overbearing mother-in-law and by a wife too weak to side with him against her. His mother and infant daughter both die, and grief-stricken, he flees. A large win at a casino and a mistaken identification of the body of a suicide as Pascal lead him to seize the opportunity to begins a new life.

Mosjoukine left Albatros after this film, pursuing his stardom in big-budget exotic historical films and melodramas, including work in Hollywood and Germany, before his death in 1939 at the age of 49. This was also Michel Simon’s first significant film; he appears in an important supporting role.

Gribiche (1925)

Gribiche is a charming film built around the talents of the boy actor Jean Forest, whom Feyder had discovered for a small role in Crainquebille.

He plays Antoine, nicknamed “Gribiche,” the son of a war widow who struggles to support him and keep him in school. As the film opens, Gribiche returns the dropped purse of a rich woman, Mme. Maranet (Françoise Rosay), and refuses the proffered reward. Maranet, having a scientific interest in children’s welfare, on a whim offers to adopt him. Knowing that his mother is being courted by Philippe Gavary, whom she hopes to marry, Gribiche pretends to want the private education promised by Maranet, and off he goes to live in her modern mansion (Meerson’s design, see top). There he is raised by servants and tutors to a strict schedule, with no time allowed for play. Meanwhile, his mother becomes engaged to her suitor.

The story contains some implausibilities. During a fairground outing with his mother and Gavary (above), Gribiche overhears the two discussing a possible marriage, but both seem worried about Gribiche. There is a hint that the man won’t propose if he has to take on a stepson. This scene motivates the whole chain of affairs. Yet Gavary seems to like the boy, and when Gribiche gets fed up with his sterile life with Maranet and runs away, Gavary is concerned and willing to take him in with no hint of discord between him and the mother. Still, the story on the whole is carried by Forest’s ability to play for both humor and pathos, the beautiful Meerson settings, and the comic business with the tutors and servants. Rosay remarkably creates a character who is friendly and sympathetic yet lacks the deeper warmth that would allow her to raise a child.

For those not familiar with Feyder’s early work, this and the next item are musts. His three most important earlier films are available on DVD, so much of the director’s silent career, previously little known, is now accessible.

Les Nouveaux Messieurs (1928)

This is a Feyder work well worth getting to know. Moving beyond his films based on stories of innocents oppressed (Crainquebille, Visages d’enfants, and Gribiche), Feyder made an adaptation of Carmen (1926) that is competent but not exciting and Thérèse Raquin (1928), which to the best of my knowledge does not survive.

Les Nouveaux Messieurs was an adaptation of a different kind, one which Borger quite rightly compares to René Clair’s late silent comedies. Taken from a popular play of the 1925-26 season, it is a satirical comedy about Jacques Gaillac, an electrician who runs for public office and briefly ends up as labor minister in a leftist government. Along the way he courts Suzanne, a ballerina who is the mistress of the wealthy Count of Montoire-Grandpré. The Count is an older man who is patiently resigned to fighting off her occasional suitors, and we see him pulling political strings on the sly.

Once again Feyder displays his talent for casting actors who can build sympathy for characters who would normally register as unpleasant. Gaby Morlay makes the mercenary ballerina appealing, someone we can believe the naïve electrician would fall in love with. Veteran actor Henri Roussell is remarkable as the Count, eschewing the obvious tropes of anger and jealousy. He is instead smart, amusing, and clearly so devoted to Suzanne that we half hope she will go back to him. The film again has Meerson settings and displays Feyder’s eye for striking visuals, both on location (above) and in the studio (below).

I recently mentioned in my discussion of Blancenieves that it was an excellent imitation of a European film made in 1928 or 1929. Les Nouveaux Messieurs is a good example of the kind of film it’s modeled on.

Coming up

Flicker Alley recently revealed that it has three releases nominated for awards in Il Cinema Ritrovato’s annual DVD awards for 2013, winners to be announced at the festival this year. Oddly, I can’t find a list of all the nominees online. When it appears, I’ll add it. The Flicker Alley nominees are: Nanook of the North/The Wedding of Palo, Feu Mathias Pascal, and “From Moscow to Montreuil.” Congratulations!

Now, if Flicker Alley will manage to release its long-rumored project, Albatros’s 1923 serial, La Maison du mystère, starring Mosjoukine, we will all be doubly grateful. For a bit of information on that and a great deal of information on various film-preservation topics, see this interview with David Shepherd, preservation expert and co-producer with Jeffery Masino of “From Moscow to Montreuil.” Nitrateville has posted a shorter interview with Shepherd, but one devoted entirely to the Albatros release.

Finally, readers who use Facebook should consider Liking Flicker Alley’s page. It lists public screenings of silent films, sponsored by itself and others alike, as well as other silent-film-related news and information about Flicker Alley releases.

The most comprehensive publication on Albatros is François Albera’s Albatros: des Russes à Paris 1919-1929 (Paris: Cinémathèque française, 1995), which contains numerous designs and on-set production photos.

My article is “The Ermolieff Group in Paris: Exile, Impressionism, Internationalism,” Griffithiana 35/36 (October 1989), pp. 50-57. (The quotation is from pages 52-53.) Lenny Borger’s “From Moscow to Montreuil: the Russian Emigrés in Paris 1920-1929,” appears in the same issue, pages 28-39, including a filmography.

Flicker Alley recently released Feu Mathias Pascal separately in a Blu-ray version.

Les Nouveaux Messieurs (1928).