Archive for May 2013

Jack and the Bean-counters

Kristin here:

I don’t know about you, but back on January 16 about the last thing on my mind was the release, still six weeks away, of Jack the Giant Slayer. It wasn’t a film I was planning to see. Not many people were, as it predictably turned out. I was more concerned with a recent release, The Hobbit: An Unexpected Journey, and whether the decision to turn a two-part film into a trilogy had adversely affected the narrative. I posted my some-good-news-some-bad-news entry that day.

Not as giant as they might think

It turned out on that same day there were some fans of fantasy films and/or Bryan Singer, the director of Jack, who were exercised about the recently released poster for the film (reproduced above). I discovered this from a Hollywood Reporter story published in the wake of Jack’s disappointing opening weekend, when it grossed $27.2 million domestically. The story led off with an anecdote about the poster kerfuffle:

When Bryan Singer sat down at his computer in mid-January and read Internet comments criticizing a new Warner Bros. poster for his big-budget epic Jack the Giant Slayer, he fumed. He didn’t care for the cartoonish image of the film’s stars brandishing swords and standing around a swirling beanstalk. So Singer complained on Twitter. “Sorry for these crappy airbrushed images,” he wrote Jan. 16, irking Warners’ powerful marketing head Sue Kroll. “They do the film no justice. I’m proud of the film & our great test scores.” An insider confesses, “Bryan felt like he had to apologize to his fans.”

This gesture annoyed studio executives, who demanded that Singer take it down. He hasn’t. The apology won him some points with the fans, as some sample tweets in response show:

Do any current Warner Bros. executives know who Saul Bass was? More to the point, do the studios have any idea how much fan devotion is gained by directors like Singer, Peter Jackson, and Guillermo del Toro, who try to communicate directly with the fans as often as they are allowed to, and even sometimes when they aren’t? If the studios did have any idea, they would encourage directors to hold question-and-answer sessions on fan sites and communicate via social media far much more than they do now. I suspect studios give up tens of millions of dollars in free publicity by treating fans as potential spies, spoiler-mongers, and authors of vicious reviews based on trailers.

Ring? What Ring?

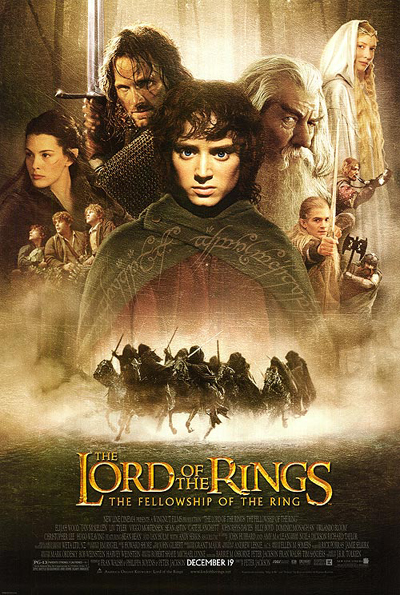

This disappointment with Jack’s poster reminded me of an incident that happened late in the filming of The Lord of the Rings. I describe it in The Frodo Franchise:

On 16 Dcember 2000, New Line’s president of domestic theatrical marketing, Joe Nimziki, met with the director concerning the Rings publicity campaign. One of his purposes in visiting Wellington was to meet the cast, who would be involved in the upcoming press junkets, parties, and premieres. The occasion soured when the filmmakers and actors saw the proposed poster design. Based on its audience research, New Line had concluded that Rings would appeal primarily to teenage boys, and the design was busy and garish. The actors backed Jackson up, threatening not to participate in the marketing campaign if it proceeded along those lines. Jackson had a mock-up poster made, featuring muted tones and a simply design centered on an image of the One Ring. The design was not used, but it gave New Line a sense of what the filmmakers considered appropriate. (p. 81)

When I made my first research trip to Wellington in 2003, I had no idea that this incident had occurred. Someone high in the production mentioned it to me out of the blue during an interview, which led me to think that this person considered it important and wanted me to mention it. After nearly three years, it obviously had remained a sore point. (I did describe the incident, but in general I portrayed the few mistakes I mentioned in my book as part of a learning curve that the studio benefited from.) Unfortunately I have never seen the offending poster design. I have seen one of what were apparently two mock-up copies of Jackson’s version made, on the basis of which I wrote the brief description above. The design was too muted in color and minimalist in layout to be useable, but it evidently served its purpose.

Obviously there’s a big difference between the handling of these two offending poster designs. New Line, which produced The Lord of the Rings, took the trouble to show the cast and crew the planned poster and acceded to their wishes about replacing it. As a result, the cast participated in the many press junkets and other publicity events. I’m not sure which poster design for The Fellowship of the Ring convinced the cast, but the one at the bottom of this entry was the main one used. Definitely better than the one for Jack at the top.

Warner Bros. presumably did not bother to show Singer the poster, or test it on fans, or do anything to make sure that it would boost rather than dampen potential moviegoers’ enthusiasm. It is as conventional a poster as one could imagine for such an expensive film.

The irony in all this is that New Line also produced Jack the Giant Slayer. Due to various post-Lord of the Rings failures, primarily The Golden Compass, New Line is now a production unit within Warner Bros. It doesn’t handle its own distribution or marketing, having been downsized by about 80 percent. Warners takes care of everything except the production itself.

Doesn’t amount to a hill of beans

Jack’s opening weekend’s gross was followed by a nearly 64 percent drop during its second weekend. It just went into second run last week, so its theatrical life is rapidly tapering off. In the same Hollywood Reporter story that alerted us to the poster tweets, author Pamela McClintock called Jack “the latest in a string of dismal 2013 domestic releases.” She added,

Revenue and attendance are both down a steep 15 percent from the same period in 2012, wiping away gains made last year. Jack may have cost far more than any of the other misses, but in assessing the carnage, there’s a collective sense that Hollywood is misjudging the moviegoing audience and piling too many of the same types of movies on top of one another.

I think that collective sense is shared by almost every ordinary viewer. Jack the Giant Slayer. Really? For that matter, Hansel and Gretel: Witch Hunters? Upon merely hearing these titles, I didn’t expect them to be hits. In the wake of The Lord of the Rings and the Harry Potter series, Hollywood has been pushing fantasy harder and harder, but there is a limit. I think that has been reached with the mini-trend toward adapting fairy tales with adults in the lead child roles. Making Jack a “giant slayer” (grammar-police note: this should be “giant-slayer”) doesn’t hide the fact that this is really “Jack and the Beanstalk” re-titled by committee.

Recently Variety reported that the success of Alice in Wonderland early in the year (it was released in March, 2010) has led studios to release films of the summer-tentpole type well before the traditional Memorial Day weekend opening of the summer season: “Warner Bros. started this year’s March madness with the pricey Jack the Giant Slayer, which never sprouted.” Disney’s Oz the Great and Powerful opened one week later.

Now there’s a film I wanted to see, and many others did, too. It’s currently still in first run and pushing toward the $500 million mark worldwide. With a reported $215 million budget plus publicity costs, that’s not a big hit (it’ll probably become profitable in Blu-ray, streaming, etc.), but it’s doing a lot better than Jack. Jack’s budget is reported at slightly under $200 million, with marketing costs of over $100 million. As of now it has grossed a little under $200 million worldwide. A week after Oz, The Croods appeared, aimed to some extent at the same audience as the two films that preceded it. In short, Hollywood is not only making a lot of children’s fantasies, adapted to a broader audiences including adults, but it is releasing them opposite each other.

Fans? what fans?

This is not to say that all such films fail. I found Oz a clever film, better than most critics have given it credit for. It presents an imaginative riff on the 1939 The Wizard of Oz as if it had been made using classical storytelling techniques but with digital technology.

But back to that claim that “Hollywood is misjudging the moviegoing audience.” It’s hard to imagine a group of executives sitting around a big table and seriously thinking that an expensive digital extravaganza based on “Jack and the Beanstalk” would bring people flocking to theaters, yet they did. Why? Possibly because they are out of touch with the fandoms they depend on.

Back when I was researching the Lord of the Rings online fandom and its relationship to New Line’s publicity department, it seemed that Hollywood was beginning to understand fans. It was a hard learning process, but New Line’s executives reluctantly gave some big websites occasional access to sets and once in a while sent them news exclusives. Such openness, grudging though it was, generated free publicity and goodwill. The studio also allowed Peter Jackson to interact with fans, though in strictly controlled circumstances.

Warner Bros. is a different animal altogether, and it has squandered much of what goodwill New Line gained in those days. The Jack the Giant Slayer poster controversy provides perhaps one clue as to how indifferent studios now are to their public and how much their insularity can damage their bottom lines.

The Hobbit: An Unexpected Journey, made by New Line under the tight control of Warner Bros., has of course done very well financially. It grossed over a billion dollars worldwide–though just barely, at $1,017,003,568. If we could adjust worldwide figures for inflation (impossible due to different inflation rates in different countries), each installment of The Lord of the Rings would undoubtedly turn out to have earned more. This despite all the surcharges for the many 3D screenings of The Hobbit.

Why didn’t it do quite as well as the previous entries in the franchise? Perhaps some people who had liked Rings were put off by their perception of The Hobbit as more of a children’s film. Perhaps it was partly the reviews, which were considerably less enthusiastic than for any of the three parts of Rings.

I wonder, though, if Warner Bros.’s lack of interest in the fans might have had something to do with it. Consider what New Line had done for fans in the marketing of Rings as compared to what Warner Bros. has done with The Hobbit. New Line started a pioneering website, managed by Gordon Paddison, that drew millions of fans long before The Fellowship of the Ring appeared. Gordon Paddison, now running his own publicity firm, has created a Hobbit website as well, but it’s primarily a large ad for the Blu-ray and DVD, with none of the free wallpapers and other items that were so popular on the Rings site. Even a live online event from March 24, during which Peter Jackson answered fan questions, was re-posted there without the brief preview footage from The Desolation of Smaug–an unkind cut that annoyed fans greatly. This was especially unfair because to log in to the live event, one needed a code enclosed in the Blu-ray/DVD package, and the Blu-ray release hadn’t occurred in many part of the world by March 24. Not good public relations.

The main online publicity venue for The Hobbit has been Jackson’s own Facebook page, where ten production vlog entries were posted at wide intervals. These later became the main supplements for the theatrical DVD release. Given the breezy, open tone of these vlog entries, it seems possible that they can be credited more to Jackson’s initiative than Warner Bros.’s.

New Line also licensed a company to create a fan club for The Lord of the Rings, complete with an excellent bimonthly magazine. A considerable amount of effort was put into the eighteen issues that appeared, including interviews not only with the filmmakers but with the makers of licensed tie-in products. Fans were encouraged to send in questions for the interviewees, and some of these got included. The names of the charter members of the club were run in a crawl after the credits of the extended-edition versions of the DVDs, a process that, even at a rather fast clip, ran for about twenty minutes. This won huge loyalty from fans, even those who joined later and didn’t get into that crawl-title.

For The Hobbit, there was no fan club and no magazine. I can imagine that the Rings fan club generated a relatively small income for New Line compared to the many other licensed items, but it created much enthusiasm among fans. The film’s official Facebook page is a feeble substitute.

For decades people have been saying that Hollywood executives are out of touch with their audiences, make too many movies, spend too much on their movies–especially in age of special-effects-based blockbusters. It’s an old complaint but one that may be a genuine and growing problem as executives with no personal film production experience control the output of studios owned by huge corporations.

The Hollywood Reporter story that began with the anecdote about Singer’s apologetic tweet ends with some insight:

Privately, studio executives concede that Jack was a feathered fish, neither a straight fanboy tentpole that Singer (X-Men, Superman Returns) is famous for nor a pure family play. “Sometimes you simply have a movie that is rejected,” laments one Warner executive, a common refrain these days in Hollywood. “You can spend as much as you want, market it a zillion different ways, and it still doesn’t work.”

Someone might point out that Jack and Rings are not comparable projects. Rings was adapted from a beloved classic and already had a significant fan base. Jack was not based on a novel and had no such fan base. But I believe that the big studios view fantasy as a genre with a broad, somewhat unified fan base consisting of people who will go to see just about any fantasy film. The failures of not only Jack and Hansel and Gretel but also of others like Mirror, Mirror show that that’s not the case.

The answer is out there

One solution to the studios’ isolation could be to get on the Internet, keep tabs of the huge amount of fan opinion already there and appearing every day, and get a sense of what the real audience wants.

One solution to the studios’ isolation could be to get on the Internet, keep tabs of the huge amount of fan opinion already there and appearing every day, and get a sense of what the real audience wants.

For a start, there is no “fantasy” fandom. There are fandoms around specific stories or series or movies or games. They create websites and Facebook pages and videos. Many fans are quite smart and understand the conventions of the fantasy genre. They know how the industry markets things to them. (Witness all the accusations that fly when a studio repackages a film yet again as a DVD/Blu-ray with only minimal changes in the supplements.) They know exactly what they want marketed to them and what they don’t want. Richard Taylor, the head of Weta Workshop, which designed many of the collectibles as well as the Rings and Hobbit films, is a hero to fans. Affluent Rings fans who get married can commission Daniel Reeves, the calligrapher for the franchise, to design their wedding invitations. Denny’s Hobbit meals, on the other hand, are viewed variously as merely amusing to downright offensive.

There are also rivalries among fandoms. Ask a Ringer and a Harry Potter fan who is the greater wizard, Gandalf or Dumbledore, and watch the feathers fly.

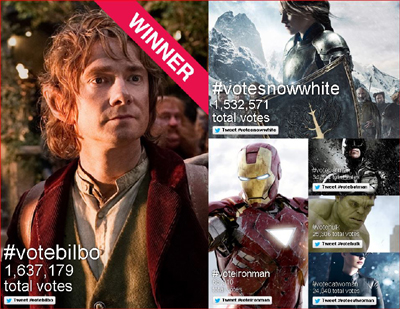

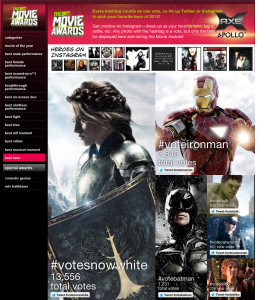

There was a vivid example of this just last month. The MTV Awards nominations for 2012 were posted for fans to vote on. In the Best Hero category there were Snow White (the Snow White and the Huntsman version), Batman, Catwoman, Iron Man, Hulk. and Bilbo Baggins. Shortly into the voting, Snow White was at first place with 13,556, with Bilbo dead last with 226 (left).

Snow White beating Iron Man and Batman? Ringers realized at once that this was not an overwhelming vote for Snow White but for Kristen Stewart, and it was happening because of the Twihards–the devotees of the Twilight series.

Rallying around, Ringers began trying to get people to Vote Bilbo. Fans created memes for tweeting and re-tweeting. TheOneRing.net, the biggest Tolkien website, got involved in helping coordinate individual efforts into a unified campaign to spread the word. Spiegel Ei posted a amusing video on Vimeo, “put a ring on it #VoteBilbo,” in which Bella Swan (Stewart’s character in the series) meets several Rings characters, reads Tolkien’s novel, researches it on the Internet, and abandons her world for Middle-earth. The short film was so clever that MTV’s website even featured a news story , linking to it–a strange case of bias that may have helped sway the voters. (The # symbol in the title comes from the fact that fans could vote only by tweeting for one of the six nominees.)

Even so, during the final exciting week, the MTV vote seesawed back and forth between Snow White and Bilbo, but the Ringers’ campaign won out, with Bilbo attaining a margin of just over 100 thousand:

Measured by the box-office records of all the films, Snow White would seem to be least popular. Yet it wasn’t the ticket-buying audience as a whole voting. It was the hardcore fans–and mostly fans from a different fandom at that.

Cliff “Quickbeam” Broadway has posted an excellent rundown of the campaign on TheOneRing.net, “When Fandom Comes Together: How #VoteBilbo Rallied the Ringers.” It conveys how a large number of devotees worked very hard for free to create an almost professional-level campaign for a character and film they loved. All this within the space of a few weeks.

I’m not saying that a studio marketer could go onto the Internet and find hard facts on fans’ likes and dislikes. It’s something one gets a feel for by looking at the message boards on TheOneRing.net or checking out The Leaky Cauldron (the biggest Harry Potter fansite) or liking a bunch of directors’ and films’ Facebook pages. By the way, it’s odd that Peter Jackson has a FB page that, with its nearly 800 thousand Likes, has become the main online publicity site for The Hobbit, while Bryan Singer doesn’t even have a FB page. Does that suggest any systematic approach in WB’s publicity campaigns? True, Jack has a FB page, but these days every film does.

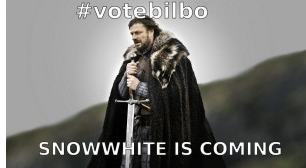

What sorts of things can you learn by looking at such sites and pages? It’s interesting, for example, that Cliff’s fandom story includes one of many images that were devised by fans for the twitter campaign for Bilbo, one not from Rings or The Hobbit, but from Game of Thrones (right). Ringers would instinctively know that Lord of the Rings fans would be far more likely to read George R.. R. Martin’s book series or watch the TV adaptation than would Twihards. Not only would they recognize the image shown (the character played by Sean Bean, who was Boromir in The Fellowship of the Ring), but they would know that “Snowwhite is coming” is a riff on a portentous line from Game of Thrones, “Winter is coming.”

What sorts of things can you learn by looking at such sites and pages? It’s interesting, for example, that Cliff’s fandom story includes one of many images that were devised by fans for the twitter campaign for Bilbo, one not from Rings or The Hobbit, but from Game of Thrones (right). Ringers would instinctively know that Lord of the Rings fans would be far more likely to read George R.. R. Martin’s book series or watch the TV adaptation than would Twihards. Not only would they recognize the image shown (the character played by Sean Bean, who was Boromir in The Fellowship of the Ring), but they would know that “Snowwhite is coming” is a riff on a portentous line from Game of Thrones, “Winter is coming.”

It is also interesting that TheOneRing.net catered to the slightly older-skewing demographic that is far more important in Rings fandom than in Twilight fandom. As Cliff says: “We have an audience that included older-generation folks who had never used Twitter, so we gave quick and easy instructions to help guide our friends toward their goal.” New Line’s audience research, which originally convinced them that teenaged boys were their primary audience, didn’t reveal that other big audience–which most Ringers would know about.

These little details may not be important in themselves, but picking up many of them from fan discussion adds up to an overall view of characteristics and attitudes. Fans are also quite clear on their likes and dislikes as far as directors and stars go. Just the other day on a thread on TheOneRing.net, Lusitano gave his opinion concerning future possible adaptations of material from Tolkien’s The Silmarillion and Unfinished Tales: “If in the future they end up being adapted, it is only sensible to give them to someone else [other than Peter Jackson]. Tim Burton, perhaps? ” Such an adaptation would, I think, be unwise, but a producer who went down that road ought to be interested in that opinion.

Clearly from the way most studios treat most fan sites, they aren’t particularly grateful for any of this. They also don’t seem to recognize that the most devoted fans working for such sites or posting on their own FB pages, YouTube, and Vimeo, have an extraordinary expertise concerning one fandom and often several.

Possibly the studios do closely monitor fansites. Certainly some people in the Rings filmmaking team read TheOneRing.net. When Guillermo del Toro was slated to direct The Hobbit, he even joined the Message Boards and participated in discussions fairly frequently. Naturally the fans adored him for it. If he had stayed on as director, would WB have allowed him to keep up that practice? Probably not unless he cleared every contribution with the studio publicity department.

I’m not saying that cruising online fan outlets would guarantee that the studios would get such a feel for their public that all the films they greenlight would be successes. There are always inexplicable flops. Why did audiences who flocked to Tim Burton and Johnny Depp’s Alice in Wonderland reject the same team when Dark Shadows appeared? Was it just the difference between the sources: a universally known classic book vs. an old TV show with a devoted but small cult following?

Still, when I hear about such incidents as the ones I’ve described here, I can’t help but feel that the fans are a far more valuable source about potential audiences than the studios realize. Why do studios not identify certain particularly knowledgeable and devoted fans as experts and hire them as consultants? Or at least quietly study what they say and do and benefit from it? Maybe then they would know what many of us already know: that the impending failure of some films, like Jack and Hansel and Gretel, is bone obvious from the start.

All this is not to say that Jack the Giant Slayer is a bad film and not worth seeing. It has gotten some surprisingly good, if not rave reviews, though its score on Rotten Tomatoes is only 52% (and 61% among fans). It’s just that WB should have known what they were getting into.

Atmos, all around: A guest post by Jeff Smith

Today we have a guest entry by our friend and colleague Jeff Smith. Jeff teaches here at the University of Wisconsin–Madison in the Film Studies area. He’s an expert on cinema sound, particularly music. His book The Sounds of Commerce: Marketing Popular Film Music is a trailblazing explanation of the ties between 1960s Hollywood and the music industry. It combines analysis of scoring with discussions of business decisions that shaped audience’s response to movie soundtracks. His forthcoming book is on how critics have understood the impact of the HUAC hearings and the Hollywood Blacklist, with emphasis on films that seem to comment on Cold War politics.

Jeff has written extensively on sound practices in contemporary American cinema. What better person to explain and analyze the newest sound technology in Hollywood movies?

Director Peter Jackson calls it “the completely immersive sound experience that filmmakers like myself have long dreamed about.” Mark Andrews, who made his feature film directorial debut with Pixar’s Brave, says, “It’s more 3D than 3D images.” “It” is Dolby Atmos, a new cinema sound system that promises to change the way you see and hear movies. Does it?

The buzz

Dolby Atmos made its debut with Brave at last year’s Los Angeles Film Festival. A handful of scenes from earlier films, including Rise of the Planet of the Apes and The Incredibles had been test-mixed in the new Atmos system for demonstration purposes. But Brave is the first film to use the new platform from start to finish.

If you haven’t heard of Dolby Atmos, you’re not alone. When Brave opened, there were only fourteen theatres in the country that were capable of showing the film in Atmos. These tended to be high-end movie theatres, such as AMC’s six Enhanced Theatre Experience venues, which typically charge a premium ticket price.

The list of theatres wired for Atmos has grown since then, but the number remains quite small. At this point, there are 37 theatres in the U.S. that feature Dolby Atmos, a tiny fraction of the country’s nearly 40,000 screens. A little more than a third of these theatres are located in California. Approximately another third are clustered in just five states: Florida, Illinois, New York, Texas, and Washington. Most of these theatres are in the suburbs of major metropolitan areas. True, the recently opened Palms Theatre in Muscatine, Iowa (population 22,886) incorporated an Atmos system in its XL Digital Auditorium, but presumably it was part of its building plan. For existing theatres, an upgrade carries a hefty price tag of between $30,000 and $100,000. So Dolby Atmos may not be coming soon to a theatre near you.

Yet more and more films are being mixed for Atmos. Dolby has announced that more than twenty films will feature the new platform in 2013, a significant increase over the twelve films distributed with this format in 2012. The roster includes three of the most eagerly anticipated studio tentpoles of the summer season: Paramount’s Star Trek Into Darkness, Pixar’s Monsters University, and Warner Bros. Superman reboot, Man of Steel. Still, does the new system justify the expensive theatre conversions and the higher ticket prices that will follow?

Two channels. Then five + one. Now, how about sixty?

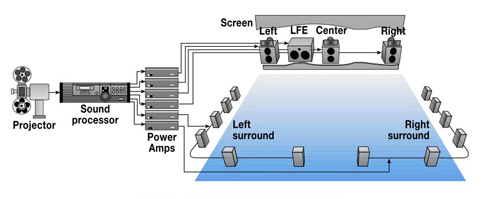

Dolby Digital Surround 5.1.

According to the Dolby website, Atmos grew out of the company’s efforts to introduce Dolby 7.1. For years, the flagship for Dolby’s digital surround sound technology was their 5.1 system. The digit 5 referred to the number of channels that could be used by sound mixers: three channels for speakers behind the screen (left, center, and right) and two channels for all the surround speakers that line the side and back walls of the auditorium (left surround and right surround). The .1 in 5.1 refers to the Low Frequency Effects channel (LFE) that sent sounds between 3 to 120 Hz to a subwoofer located behind the screen in the front of the auditorium. These low-frequency sounds trigger acoustic vibrations that add a kinesthetic kick to onscreen explosions and car crashes.

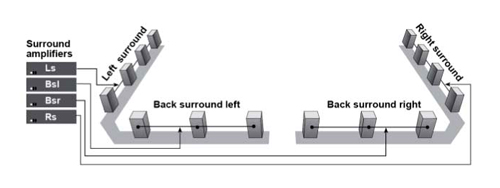

With Toy Story 3 in 2010, Dolby introduced two additional channels to their 5.1 platform. The 7.1 system subdivides the surround speakers. Instead of two channels for the surrounds (left surround and right surround), Dolby 7.1 offers sound mixers four channels (left side surround, left rear surround, right side surround, and right rear surround).

Dolby 7.1 came fairly late to the game, however. Sony already had introduced its own 7.1 system in 1993 with the premiere of John McTiernan’s Last Action Hero. Yet despite the eight-channel capability of Sony Dynamic Digital Sound, (SDDS), it never really caught on, largely because of the added expense of executing a 7.1 sound mix in addition to the standard 5.1 one. To date, more than 1400 films were mixed for the six-channel version of SDDS. Only 97 films received an eight-channel mix.

In the 2000s, Sony gradually began to phase out its 7.1 system. Filmmakers stopped building eight-channel mixes in SDDS in 2007. Moreover, about ten years after introducing SDDS, Sony stopped manufacturing decoders for SDDS content, citing decreased demand. SDDS had always lagged behind its competitors in the battle for screens, so Sony’s decision was not terribly surprising. Although new films continue to be mixed in SDDS to meet the needs of exhibitors that continue to use the system. Most theatre owners have replaced SDDS with one of Dolby’s systems. Sony promised exhibitors it would continue to make parts and service for current SDDS products available until 2014. But the electronics giant acknowledged that it was shifting its attention to digital cinema technologies that were already in development.

Considering Sony’s history and exhibitors’ reluctance to upgrade to an eight-channel system, it’s surprising that in 2010, Dolby would launch its own 7.1 counterpart. But maybe not so surprising, because Dolby’s new channels were differently placed. Sony’s 7.1 system had added channels to the speakers behind the screen. Instead of three front channels (left, center, and right), SDDS had five (left, left center, center, right center, and right). These extra sound sources probably made little difference to most moviegoers. Adding channels behind the screen made for smoother panning of sounds that seem to move across the space depicted in a shot, but it did nothing to increase the sense of spatial immersion.

In contrast, Dolby added its two extra channels to the surround areas. Its 7.1 platform treats the interior of the theatre as seven spatially distinct zones. The additional channels in the surround array enables mixers to position sound elements more precisely. This “zoning” of the surrounds offers mixers a wider variety of options for the placement of sounds, and it more closely approximates the way that sounds in real life come at us from several different directions.

Now Dolby Atmos pushes the premises of this aspect of Dolby 7.1 to the nth degree. While Dolby 7.1 makes a leap from six channels to eight channels, Dolby Atmos makes a leap from eight channels to sixty-four channels, a gigantic change from all of Atmos’ predecessors. Using the old nomenclature that described the sound platform as a ratio of speaker channels to LFE channels, we might call Dolby Atmos a 62.2 system! It offers more than sixty separate and distinct speaker channels as well as an optional channel for additional subwoofers located in the back corners of the auditorium. More importantly, with the vastly expanded number of speaker channels, Atmos enables mixers to position a single sound element in the theatre with unprecedented clarity and precision.

Say you have a screen door banging in the wind. In Dolby 5.1, if a mixer wanted to send that banging noise to the right surrounds, it went to every speaker in the array. In effect, it wouldn’t sound like a single door, but rather several doors banging in unison. In Atmos, however, if a mixer wants to position that banging sound in a particular part of the auditorium, he can treat it in a manner analogous to the way it would be heard in the real world. The sound is emitted from a single point of origin and is heard as a punctual effect rather than as aural ambience emanating from a broader area of the theatre.

All about the panning

Beyond its multiplication of channels, Dolby Atmos addresses certain limitations in earlier platforms. Simplifying a bit, we can say that for content providers Atmos is “all about the panning.” Atmos adds a couple of speakers on each side that are placed close to the screen to facilitate smoother pans for sounds that move from onscreen to offscreen.

The surround speakers in Atmos have a frequency range that closely matches that of the speakers behind the screen. This aspect of Atmos addresses a common complaint about more traditional digital surround systems. In those, the surround speakers have a narrower frequency range than the front ones. As a result, when sounds were panned from onscreen to offscreen, the audience could hear changes in timbre and fidelity. The extra subwoofers in Atmos ameliorate this problem since they help to “bass manage” the surrounds, thereby allowing sounds in them to have a much “fatter” low end.

Besides adding subwoofers to increase the number of LFE channels, theatre owners have the option of adding left center and right center channels to the speakers behind the screen. This allows for smoother pans of sounds made by characters or objects that move across the screen. In this respect, Atmos combines the best features of Dolby 7.1 and Sony’s eight-channel system.

Up in the air

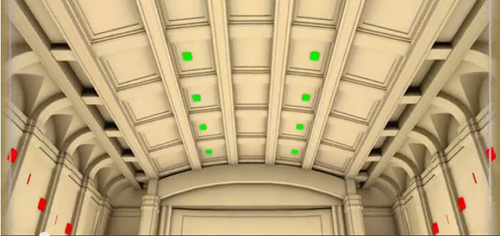

In platforms like Dolby 5.1, sound is situated almost entirely on one plane. The speakers behind the screen are at roughly the same height as are the surround speakers that line the sides and back wall of the auditorium. Dolby Atmos expands the auditory field by adding speakers to the theatre’s ceiling.

These additional speakers create an overhead sound plane, which enhances the sound mixer’s ability to localize sounds in the auditorium. In real life, of course, we hear all kinds of things overhead–bird calls, airplanes, building construction. Although mixers can use these ceiling speakers for sounds that are important in the story that unfolds onscreen, Dolby’s literature usefully reminds us that overhead ambient sound can enrich a film’s setting. A chirping cricket placed in one of the overhead speakers can convey the feeling of sitting at night beneath a forest canopy.

Admittedly, this new feature of Atmos technology merely represents a refinement of something filmmakers could do before. But previous sound technologies suggested an overhead sound plane through a psychological illusion. When the characters in Das Boot, for example, hear the pinging sounds of a British destroyer’s sonar system above their submarine, we might hear that sound originating above our heads. Yet its point of origin is no different from any other sounds that we hear in Das Boot.

Characters’ upturned gazes bias our response as we watch them anxiously awaiting the detonations of the depth charges released by the destroyer.

The extra surround channels and the overhead sources all create a more enveloping ambience and more punctual sound events—ultimately, a more realistic aural environment. Dolby’s innovations should be especially appealing for films projected in 3-D. Atmos, as its proponents note, offers a 3-D sound to match 3-D picture.

Is the recent popularity of 3-D cinema, though, the only factor in Dolby’s push to get more exhibitors on board with Atmos? Curiously, it comes right on the heels of Dolby’s introduction of its 7.1 system. Over the years, Dolby has continually pressed its R & D division to develop new sound technologies. But, in bringing both Dolby 7.1 and Atmos to the marketplace in about a two-year time span, I still have to wonder, “Why now?”

Backward compatibility

Fans of Atmos argue that it represents nothing less than a paradigm shift for cinema sound technology. That may prove to be true if more exhibitors decide to invest in it. But if we are witnessing a paradigm shift, it is one made possible by another paradigm shift, one of even greater historical import. I’m thinking here of the sweeping change that took place as theatres changed to digital projection.

David has written extensively on this topic, and you can find his account of this change in his e-book, Pandora’s Digital Box, a recasting of several blog entries under that name. Actually, the shift to digital projection didn’t demand Atmos. But it certainly made it possible.

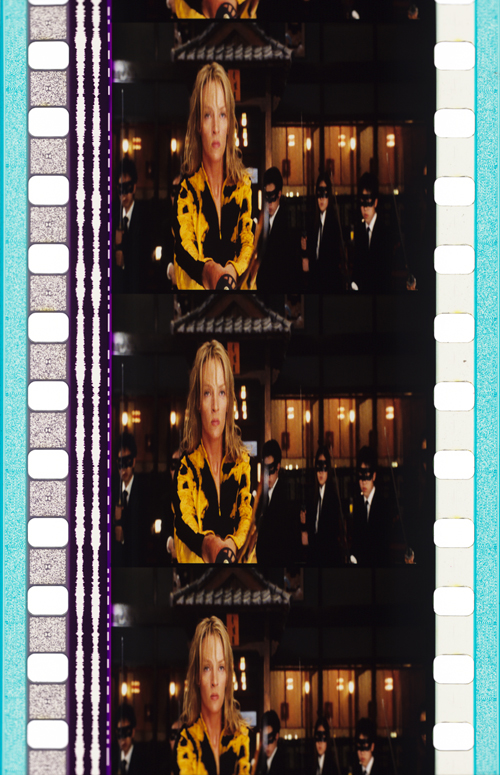

Look closely at a single frame of 35mm film. Like an archeological record, it preserves thirty-plus years of cinema sound innovation. Left of the picture area, you can see the twin optical sound stripes, encoded as wavy lines, that are used for older Dolby Stereo systems. Dolby continually refined its initial four-channel stereo system, ultimately introducing Dolby SR in 1986 as the last generation of its signature noise-reduction technology. (The SR stands for Spectral Recording.) These optical stripes on a 35mm print are still necessary for any theatre still using analog sound.

Just to the right of these optical stripes you can see dashed white lines used for DTS time code. DTS is a digital surround sound technology that uses compact discs to store and play back the film’s audio. The white lines maintain sync between picture and sound.

On the extreme left and right edges of the film strip, outside the perforations, is a speckled light blue stripe. That encodes the audio data for SDDS playback. The information in the two stripes is redundant, but that’s necessary because SDDS is decoded by a sound reader that mounts on the top of a 35mm projector. By putting the information on both sides of the frame, Sony’s design avoids any potential problems in threading the SDDS decoder.

Lastly, in between the sprocket holes on the left side, you can see the audio information for Dolby Digital. Like the SDDS stripes, these gray patches of Dolby Digital audio are encoded as data blocks that are read by a digital sound head. They send the information to a Dolby Cinema Sound Processor.

In our 35mm strip, a huge amount of audio information, along with the film image itself, is jammed into a space that’s less than an inch and a half wide. Throughout the 1990s and 2000s, this “quad track” – that is, one analog system and three digital formats – proved to be very versatile. The audio could be played back in any theatre, regardless of the particular type of sound system that is used. The quad track allowed studios to avoid the distribution nightmare of having to match prints to screens using different audio systems. The one-size-fits-all approach also enabled multiplex exhibitors to move a print from one screen to another without worrying about compatibility.

But suppose we had to add another type of audio data to 35mm film, one that is capable of supporting more than sixty different audio channels. There just isn’t enough empty space on a 35mm print to make such an innovation possible. So even if Dolby’s engineers envisioned the potentiality of an overhead sound plane and of a cinema sound processor capable of supporting 64 different outputs, there was no practical way to add the audio information needed for Dolby Atmos and retain the compatibility offered by the quad-track 35mm.

Enter the Digital Cinema Package. With the large-scale conversion to digital projection, the prospect of innovating a system like Dolby Atmos suddenly took on new life. The audio files for Dolby Atmos are embedded in the DCP alongside the files for 5.1 and 7.1. Like the audio in 35mm film, the DCP is designed for maximum compatibility. The Dolby Atmos files are ingested into the theatre’s server along with all of the other audio and picture files found in a DCP. But for any theatre that is not wired for Atmos, the server simply ignores the Atmos files and uses the main audio track file for standard playback. More importantly, if there is any communication problem between the server and the Atmos sound processor, the system simply reverts to a Dolby Surround 7.1 or 5.1 mix, ensuring that a show can continue without delay. Even more impressively, the Atmos system even detects a damaged speaker or amplifier. Its flexible rendering system automatically works around the faulty component, sending the necessary audio data to other parts of the replay chain. So a show will continue despite a technical problem, and a narratively important sound effect or line of dialogue will not be lost due to a damaged speaker or amplifier.

The backward compatibility found in the Atmos system has long been an aspect of Dolby’s business strategy. When Dolby introduced its four-channel Stereo technology in 1975, it did so in a way that accommodated the needs of theatre owners who wanted to retain their existing sound systems. Dolby Stereo used a matrix system that mixed four channels of audio information down to the binaural optical stripes found on a standard 35mm print. After the projector’s sound head read these optical soundtracks, the information contained in them was then sent to a sound processor that “unpacked” the binaural stereo and sent the signals to the appropriate speakers in the auditorium. Dolby’s matrixing system, though, was prone to certain amount of cross-talk between the screen channels, and it occasionally caused a sound to be sent to the wrong output in the four-channel mix.

As a company concerned about backward compatibility, Dolby was willing to live with trade-offs. On one hand, the Dolby matrixing system avoided the kinds of format complications found in multi-channel systems that used magnetic striping. On the other hand, because of the potential for bleed between channels, some sound editors were reluctant to experiment with directional sounds in Dolby Stereo mixes. In practice, the surround channel in Dolby Stereo was reserved mostly for ambient noise, things that added texture to a film’s aural environment but that did not flaunt the precise directionality made possible by multi-channel playback.

Sound historians Jay Beck and Mark Kerins point out that such timidity has also characterized a good deal of sound work in the Digital Surround era. Contemporary sound designers strive to create immersive audio environments for films, but they also opt not to localize specific sounds that would draw our eyes away from the screen. In particular, designers shy away from assigning sudden loud sounds to the rear surround channels. Because the sound originates behind the audience, viewers are likely to be startled, which can be inappropriate to the mood of the story. Worse, the audience may turn to see what caused the unexpected noise. This is called the “exit-door” effect, because it pulls the viewer out of the story as if somebody had slammed the emergency exit.

Sound editors are much bolder about localizing individuated or punctual sounds in an Atmos mix. With 64 different channels to play with, Atmos offers myriad possibilities for audio experimentation. For content-providers, Atmos presents a “brave new world” for cinema sound. But this leads to a larger question: What is it like to see a film in Atmos?

Multi-channel sound with a Scottish lilt

While I was in Los Angeles last August doing research, I decided to spend a sunny Sunday morning at the movies. The City of Angels has a bevy of terrific movie theatres showing Hollywood’s latest, but the choice was easy. I headed to see Pixar’s Brave at Hollywood’s El Capitan Theatre, then one of only ten theatres in the country wired for Dolby Atmos.

El Capitan opened in 1926 as one of three theatres run by legendary showman Sid Grauman. Unlike Grauman’s nearby Egyptian and the famous Chinese Theatre, El Capitan was a venue for live performances. After a decline in attendance in the late 1930s, El Capitan was refurbished and reopened as the Hollywood Paramount Theatre. For several years, it remained a flagship for Paramount Pictures until the late 1940s, when the U.S. Supreme Court and the Justice Department forced all of the studios to divest their exhibition holdings. Until 1991, El Capitan was owned and managed by a series of different companies, including the Pacific Theatres Circuit.

That all changed in the late eighties when Disney offered to lease El Capitan from Pacific Theatres with an eye toward using it as a venue for premiering new films. Disney spent millions restoring the theatre’s original décor, although it seems to have been “imagineered” into a faux 1920s picture palace, complete with a Mighty Wurlitzer organ. Disney also restored El Capitan’s original name perhaps in an effort to sever the theatre from its earlier associations with Paramount. El Capitan is now Disney’s own flagship theatre in Hollywood and is fully integrated with their other businesses. Indeed, the Sunday morning that I attended Brave I was surrounded by families visiting it as one of the stops in Disney tour packages.

As a premium venue, El Capitan offers much more than your usual movie experience. As I walked in to find a seat, a talented organist played a medley of songs from classic Disney films, like Pinocchio’s “When You Wish Upon a Star,” and from more recent titles, such as Toy Story’s “You’ve Got a Friend in Me” and The Lion King’s “Circle of Life.”

There was plenty of other pre-show entertainment.: a couple of trailers, a brief light show, and song and dance numbers featuring costumed Disney characters. Unlike the organ medley, though, these live performances did not use music from Disney films, but instead drew from the Great American songbook. Mickey and Minnie danced to Astaire-Rogers tunes, followed by patriotic songs, including George M. Cohan’s “You’re a Grand Old Flag” and “The Yankee Doodle Boy.” The program culminated with a short medley of Scottish songs that introduced Disney’s newest princess, Merida.

This final number provided a more or less seamless segue into the start of Brave.

I didn’t know quite what to expect from the film, which has hailed as a change of pace for Pixar, a company that had developed a reputation for targeting a “family film” demographic centered on pre-teen boys. Despite the fact that Pixar had broken new ground with the film’s red-haired, tartan-clad heroine, Brave received middling reviews. By August, it was perceived as a bit of an underperformer, having earned “only” half a billion dollars worldwide. (Such is the high bar set by Pixar titles.)

I quite enjoyed Brave, not least because it was in Atmos. For the most part, Atmos lived up to the hype, offering a sonic experience that was unlike anything I’d heard in theatres before. In a way, Atmos simply refines things that could be accomplished in Dolby 5.1 or 7.1. Yet certain moments of Brave lived up to the promise of a fully three-dimensional sound that matches a film’s 3-D images. I’m not an audio engineer or sound technician. I’m really just a guy who likes going to the movies, albeit one who is a tad more attuned to the vagaries of digital surround sound mixes. So I’m offering some “in the moment” impressions of the Atmos system. If I’ve made any grievous errors in description, chalk it up to either faulty memory or the power of cognitive illusion.

I first became aware of Atmos as something different early on during a rather ordinary scene in which Merida receives “princess training” from her mother. As Merida recites a poem, the Queen, standing above her, instructs her to project her voice saying, “Enunciate! You must be understood from anywhere in the room or it’s all for naught.”

Cut to Merida. When she replies under her breath, “This is all for naught,” the Queen shoots back “I heard that!”

During this brief shot that holds on Merida, Emma Thompson’s mellifluous response as the Queen issues from one of the left rear surround speakers.

The localization of the Queen’s voice creates a brief “point of audition effect” as it realistically places us in the middle of the diagonal space that separates Merida from her mother. The moment also playfully demonstrates the Queen’s instruction to Merida to be heard from “anywhere in the room.”

Another example of Atmos’ innovative use of offscreen sound occurs during the family dinner scene in which Fergus is retelling the story of his confrontation with Mordu. After Merida sits down at the table, Fergus is about to take a bite from a leg of poultry. At this moment, we hear the sound of barking dogs swiftly panned through the right side surround speakers in the auditorium.

The dogs then burst into the frame from off right.

The use of spot sound effects in the surround speakers is quite conventional, but the panned barking had a smoothness and swiftness that I had not heard before.

This moment is interesting for another reason. Although this is admittedly a bit speculative, I believe it showcases Atmos’ ability to exploit a kind of aural correlate of the Phi Phenomenon. The Phi Phenomenon refers to an optical illusion involving the movement of light. Gestalt psychologist Max Wertheimer noticed in experiments conducted in the early 1910s that when two lights were flashed on and off rapidly enough, subjects saw them not as two flashing lights, but rather as a single light that appeared to move back and forth. Many neon signs exploit this perceptual illusion.

The same is true of this rapidly panned sound in Dolby’s Atmos, which is made possible by the system’s “pan-through array.” Because the sound editor can use positional metadata to send the sound of the bark to each of the right side surround speakers for just a couple milliseconds of time, our mind does not hear it as a group of fragmented sounds, but instead hears it as a single sound that zips through the space of the auditorium.

Later, while galloping in the woods, Merida finds herself thrown into the middle of a Stonehenge-like circle. As Merida gets her bearings, we hear a breathy, echoey, high-pitched sound coming from one of the right surround speakers. Cueing us by Merida’s glance into the space off right, director Mark Andrews cuts to a shot over Merida’s shoulder that shows a blue wisp off in the distance.

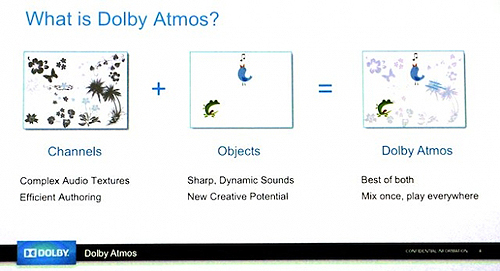

The use of a sound effect in the surround channels to steer our attention to offscreen space may be one of the most conventional aspects of digital sound aesthetics. Yet this moment is a bit unusual. It positions one localized sound effect against a bed of ambient sounds that are sent to all of the speakers in a geographical zone. In fact, this is an aspect of Atmos that Dolby showcases to content-providers. Unlike systems that are wholly channel-based, Atmos allows sound editors to locate a single sound effect in an individual speaker at the same time that other groups of sounds are fed to the system as a channel-based submix. The combination of “beds” and aural objects is captured in a visual diagram provided by Dolby.

The graphic of the bed shows a variety of gray-colored flora and fauna. The aural objects are represented as a green frog and a blue songbird. When the two images are combined, the green frog and blue bird stand out as individually colored objects set off against the bed of gray background elements. Background and foreground effects can all be developed individually and then blended at a later stage of postproduction. Atmos refines the creative possibilities found in other digital surround sound systems in a way that preserves current workflows.

Up until now, I have not said much about Atmos’ ability to exploit an overhead plane of sound. This may strike you as a bit curious since the legendary sound designer, Gary Rydstrom, discussed this aspect of Atmos in the Hollywood Reporter as one of the technology’s most appealing features. Describing a scene where Merida goes to retrieve an arrow that she has launched, Rydstrom says:

You hear the arrow ‘swish’ go through the theatre and land way back behind the audience. Then she goes into the forest. I love putting sound in the ceiling, things like scary forest birds. For a little girl, the forest feels even taller and more imposing if you can have weird sounds way up high.

Rydstrom’s description beautifully captures the way this moment from Brave works onscreen. Yet because I had read his comments before seeing the film, it was a little less powerful than some other events on the overhead sound plane. A moment I found more striking comes when the queen realizes that a magic spell has turned her into a bear. The bear flails about the room, ultimately falling backward onto her four-poster bed.

After falling through the bottom of the bed, the bear then bolts upright to smash through the canopy. Aurally, this moment is rendered as a loud crash located in the speakers suspended from the ceiling. The placement of the sound beautifully punctuates the bear’s sudden upward thrust, adding a sonic punch to the sight gag.

Probably the most vivid demonstration of Atmos’ capability comes in a scene in which Merida is caught in a thunderstorm. Sitting in the balcony of El Capitan, I felt pulled into the thick of events unfolding onscreen. If you shut your eyes, you could almost feel the patter of raindrops, the whoosh of the wind, and the violent clamor of thunderclaps.

Admittedly, such scenes can seem pretty powerful in a theatre using a more conventional digital surround system. A Dolby 5.1 or 7.1 mix can create comparable aural immersion by simply sending submixes of the storm’s sounds to different zones within the theatre. I suspect that the impact of the Atmos mix came less from its ability to isolate particular sound effects than it did from the additional subwoofers placed in the back corners of the theatre. With three subwoofers, loud sounds seem flung at you from all directions. Thanks to the additional LFE channel, the sound waves from those thunderclaps triggered even stronger shakes and rumbles. (The extra subwoofers also enhanced Mordu’s ferocious roars during the epic confrontation, shown up top, that resolves Brave’s plot.) The overhead speakers also played a subtle role in creating the feeling of being caught in a storm. The sense of a three-dimensional environment is undoubtedly heightened by the sound of rain droplets falling and spattering above one’s head.

Is Dolby Atmos the great leap forward for cinema audio that its proponents claim? The answer depends upon the weight you place on potentiality vs. established practice. Atmos definitely creates opportunities for precise placement of sounds in the auditorium. That in turn offers new prospects for audio/visual coherence. As Dolby puts it in the white paper: “If a character on the screen looks inside the room toward a sound source, the mixer has the ability to precisely position the sound so that it matches the character’s line of sight, and the effect will be consistent throughout the audience.”

Yet the specific purposes to which Atmos was put in Brave – the use of spot sounds to activate offscreen space; the use of surround speakers for panned or moving sounds; the creation of a immersive, 3D aural environment; the use of loud noises to viscerally impact the audience – are all things that its predecessors accomplished, going all the way back to Dolby’s pioneering four-channel system. Atmos does these things either a little better or a lot better, depending upon the specific system you’re comparing it with.

Perhaps my description of Brave suggests that the advantages of Atmos are more subtle than spectacular. Perhaps you feel that contemporary movies are sound-polished enough already. If so, Atmos probably won’t hold much appeal for you as a moviegoer.

The bigger question for me is whether it will be widely adopted by theatre owners. A key aspect of Dolby’s sales pitch for Atmos is that it is scalable to almost any size of theatre. If your theatre is too small for a 62.2 configuration, you can reduce the speaker array and get some of the benefits of Atmos’ improved surround definition and overhead sound plane. Dolby says its minimum configuration for Atmos is 9.1. But if the best that you can do for your theatre is 9.1, then perhaps Dolby’s 7.1 system is a more sensible option.

The exhibitor’s ability to mix and match components in Atmos was something I experienced firsthand during a recent visit to the ShowPlace ICON in Chicago. The ICON has two screens wired for Atmos, but those auditoriums weren’t equipped with the optional subwoofers that were in the system at El Capitan. Why? With two additional subwoofers, there is increased risk of sound bleeding over to the neighboring auditoriums of a multiplex. This wasn’t a problem for El Capitan, a huge, standalone theatre.

In any case, the costs to upgrade all the screens in a multiplex would be prohibitive, particularly at a time when many theatre owners are still smarting from expenditures of converting to digital projection. For that reason, Atmos may be introduced as 3D was, with one or two screens per venue at first. The decision to do an Atmos upgrade may devolve upon the question of what particular sound system is good enough to meet the needs of both theatre owners and patrons.

Yet the threshold for “good enough” is not static, and theatre owners may find themselves under increasing pressure as home theatre technologies become ever more sophisticated. If Quentin Tarantino is right that watching digital projection in a movie theatre is like watching a giant television screen in someone’s living room, then Atmos really offers exhibitors something to differentiate the multiplex from the home theatre. With 4K televisions already showing up at big-box retailers, cinema audio may provide exhibitors with the best means of luring movie fans out of their living rooms. After all, are you really ready to deploy a couple of dozen speakers around your walls and from your ceiling?

At several points in this post, I cited information made available in a white paper prepared by Dolby that explains the key features of Atmos to content providers and exhibitors. Additionally, Dolby’s website offers lots of other information about their Atmos system: a list of theaters wired for Atmos, a roster of films mixed in the process, and a short video explaining some of the differences between Atmos and other systems.

Information about Brave in Atmos can be found in two articles published by The Hollywood Reporter that are available here and here. There’s also a video interview with Brave’s sound design team. A brief history of the El Capitan can be found on the theatre’s website.

Film scholars Jay Beck and Mark Kerins both have written excellent histories of Dolby’s Atmos’ predecessors. Beck’s 2003 Ph.D. dissertation, “A Quiet Revolution: Changes in American Film Sound Practices, 1967-1979,” offers a terrific account of Dolby’s innovation of its pioneering four-channel stereo system. For a sampling of Beck’s analysis of Dolby Stereo aesthetics, see his essay, “The Sounds of ‘Silence’: Dolby Stereo, Sound Design, and Silence of the Lambs” in Lowering the Boom: Critical Studies in Film Sound, coedited by Beck and Tony Grajeda. Kerins’ work, on the other hand, focuses more squarely on Dolby 5.1 and what he calls a “digital surround sound style.” See Kerins’ Beyond Dolby (Stereo): Cinema in the Digital Sound Age.

For more on Atmos, see Eric Dienstfrey’s excellent explanation on our UW media blog, Antenna.

Wanda, the biggest cinema chain in China and purchaser of the AMC chain in the US, recently announced a major commitment to Atmos in its Mainland cinemas.