Innovation by accident

Tuesday | September 10, 2013 open printable version

open printable version

DB here:

The old drama is being reenacted before our eyes, and as often happens, Harvey Weinstein plays the villain. The American release version of Wong Kar-wai’s The Grandmaster, which has cut and changed the original, is being decried as a travesty, the dilution of an artist’s original conception in the name of what somebody thinks will sell.

I take up The Grandmaster in another entry. For now, I just want to point out the archetype goes back long before Harvey came on the scene. A screenwriter or director comes up with a fresh approach to telling the story. But a producer rules it out as something the audience won’t buy, or even understand. Moral: In Hollywood, the creative force is stifled by a money person who insists on doing things as usual.

The 1940s in Hollywood was an era of narrative innovation. It gave us weird dream sequences and insane protagonists and subjective point of view and byzantine flashbacks and talking houses and complicated replays of action we thought we understood. While working on a book on this era, I’ve begun to wonder what the limits of innovation might be. What could make the boss tell the filmmaker that a particular narrative choice just went too far?

Fasten your seatbelts, it’s going to be a bumpy production

A Letter to Three Wives (1949).

One example I found was purely anecdotal, but nifty nonetheless. In preparing the screenplay for Out of the Past (1947; aka Build My Gallows High), screenwriter Daniel Mainwaring wanted to have the story told by a deaf-mute boy. Apart from the fact that the boy plays a minor role in the opening of the film as it was finished, the idea of someone who cannot hear or speak serving as narrator proved to be something of a stretch for the time. Mainwaring reports that the idea was rejected.

That’s the kind of thing I wanted to find. Yet my searches sometimes came up with cases where the producer’s notes actually resulted in improvements. Take A Letter to Three Wives (1949), justly praised as one of the best films of the 1940s.

John Klempner’s original novella (published in 1945) and novel (1946), both titled A Letter to Five Wives, obviously involved two more couples. After some other writers had drafted versions, Vera Caspary was assigned to prepare a treatment. Probably with the input of producer Sol Siegel, she eliminated one couple. Her adaptation already contains much of what is distinctive about the movie as we have it. Instead of the many distributed flashbacks in the originals, the treatment consolidated them into three lengthy ones. At Siegel’s suggestion, Caspary brought the three women together on the boat. To Fox studio chief Darryl F. Zanuck we apparently owe the idea that one woman, Deborah, would be the primary vehicle of our sympathy and would initiate and resolve the mystery of whose husband has defected. Above all, Caspary’s treatment includes the unforgettable voice-over of the never-seen Addie Ross.

When director Joseph L. Mankiewicz saw Caspary’s final adaptation, in effect “A Letter to Four Wives,” he declared he “looked upon the Promised Land” and quickly turned it into a screenplay. After reading Mankiewicz’s screenplay, Zanuck intervened again , demanding that another wife be lopped off. Mankieiwicz called this “an almost bloodless operation.”

It’s probably irrelevant that A Letter to Three Wives won that year’s Academy Awards for best screenplay and best direction. Even if it hadn’t been honored, after reading the original tales and Caspary’s adaptation, I have to conclude that the film is the best version of the lot. I suppose it partly goes to show the old rule that bad or so-so books can make very good movies. (Exibit A: The Birth of a Nation; Exhibit B: The Magnificent Ambersons; Exhibit C: The Godfather. Defense rests.) But clearly, the cuts and changes demanded by Siegel and Zanuck improved the property. The “creatives”–Klempner, Caspary, Mankiewicz–were by force majeure steered toward good results.

You can argue, though, that no written version of the film tried to be innovative, except perhaps for the device of Addie’s spectral presence. And Mankiewicz declared himself happy to make the adjustments. What about cases in which genuinely bold ideas were curtailed by the powers above? So I looked into two titles that, when released in the producers’ cuts, were denounced by their writer-directors.

Two years after Preston Sturges finished and cut his film about the discovery of ether anesthesia, Paramount producer B. G. “Buddy” DeSylva supervised and released a reedited version called The Great Moment (1944). Sturges noted of the film:

It is coming out in its present form over my dead body. The decision to cut this picture for comedy and leave out the bitter side was the beginning of my rupture with Paramount. . . The dignity, the mood, the important parts of the picture are in the ash can.

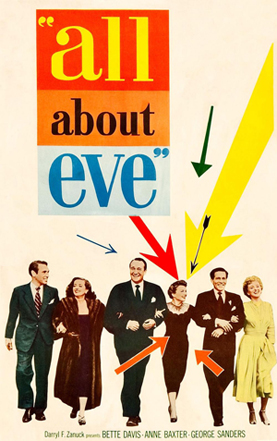

A second example is a more famous release, Twentieth Century-Fox’s All About Eve (1950). After the success of A Letter to Three Wives, Zanuck allowed Joseph L. Mankiewicz to film his three-hour screenplay as a “shooting draft.” When Zanuck saw the result, he insisted on cutting it to 138 minutes.

Throughout his life Mankiewicz was an angry man. His interviews and writings excoriate mothers, film festivals, doctors and nurses, Michelangelo Antonioni, television, the American male, theatre operators, Graham Greene, the AFI, PBS, Richard Nixon, Dennis Hopper, The Untouchables (film version), British craft unions, and other malefactors. High on the list was Darryl F. Zanuck. Long before the Cleopatra debacle, Mankiewicz was already carrying a grudge because Zanuck removed a replayed scene from All About Eve. He definitely didn’t consider that a bloodless operation.

Zanuck had final cut and he got bored with the same scene shot from different points of view.

Here, I thought, were sterling examples of creators bumping up against what was impermissible. Yet the more I looked, the more I found that the situation couldn’t be reduced to the daring director versus the philistine producer. I was forced to consider the possibility that the producers’ changes yielded not timid conformity but instead some unpredictable results–things that were themselves novel, in intriguing ways. The suits hadn’t intended to do something bold, yet in revising and patching up the films shot by two venturesome directors, they actually found themselves pulled in new directions.

Call it inadvertent innovation. Not surprisingly (this is the 1940s), it involved flashbacks.

Which great moment?

Kitty Foyle (1940).

By the early 1940s, movie flashbacks adhered to several conventions that we still recognize. Typically, we’re given a situation, the narrative Now, in which a character is recounting or simply remembering past events. We then move to those events, a shift often signaled by a track-in, a musical cue, a dissolve or other optical effect, and/or sounds from the next sequence mingling with the spoken transition. We may hear the voice-over remarks of the lead-in character at times during the action we see. Once the flashback action is complete, we return to the present, with the character who launched the flashback finishing the testimony or closing off the memory. And if the film includes several flashbacks, they are typically presented chronologically, so that the earliest events from the past are shown before later ones.

Kitty Foyle (1940) offers a clear example. In the present, Kitty recalls her romances. As they develop, we return to the present at key moments to gauge her reactions. For the sake of clarity, the romances themselves are shown to us in 1-2-3 order, tracing the events that lead up to the crisis that launched her memory journey.

Not all flashbacks respect chronology, though. Citizen Kane’s first flashback traces Kane’s career as the banker Thatcher knew it. His recollections show us Kane as a child, a young man, and then a much older man forced to sell his newspaper empire. The next flashback, as recounted by Kane’s business manager Bernstein, takes us back to show Kane as a young man assuming control of his first newspaper. Several years before Kane, Sturges had composed a script based on similarly shuffled chronology. The Power and the Glory (1933), directed by William K. Howard, presents an old man recalling episodes in the life of tycoon Thomas Garner, and those are presented out of 1-2-3 order. (I analyze that film here.)

Sturges was confronted by the problem of order in preparing Triumph over Pain. This project would tell the story of Dr. W. T. G. Morton, the popularizer of surgical anesthetic. Biographical films about scientists and inventors had become a successful cycle in the late 1930s, but Sturges wanted to stay fairly close to the facts. The problem was that Morton’s story couldn’t lead easily to a triumphant finale. Sturges noted dryly:

Dr. Morton’s life, as lived, was a very bad piece of dramatic construction. He had a few months of excitement ending in triumph and twenty years of disillusionment, boredom, and increasing bitterness. . . . To have a play you must have a climax and it is better not to have the climax right at the beginning.

Accordingly, Sturges had somehow to rearrange portions of Morton’s life.

Since [the writer] cannot change the chronology of events, he can only change the order of their presentation.

The title Sturges gave to his final version, Great without Glory, indicates its tone. A quasi-documentary prologue hails the modern benefits of anesthesia. We move to the late 1800s, when Morton’s friend Eben Frost finds a medal given to Morton now sitting in a pawnshop. He brings the medal to Morton’s widow Elizabeth, and as they sit in her parlor, the film’s first long flashback starts. It presents the public celebration of Morton’s triumph, as he and Eben are driven through the crowded streets.

The ensuing scenes trace the aftermath of his discovery—the fact that he could not patent it, his efforts to build a business on sale of ether bottles, a bout of illness, and then his receiving the medal while he is plowing on his farm.

Sturges’ version returns to the narrating frame, as Eben examines some more personal memoirs that Elizabeth has written. The second flashback initiates the play with chronology. It traces events leading up to the action we saw completed at the start of the first one. The plot takes us back to the couple’s courtship, the first years of Morton’s dentistry practice, and his arduous experiments with ether. He finds prosperity using it on his patients. Challenged to demonstrate his invention in a public surgical operation, he realizes that his demonstration will show his rivals his trade secret. He is about to leave the operating theatre when he sees the patient: a girl about to have her leg amputated. Unable to let her face agony, he turns back to reveal his discovery to his peers.

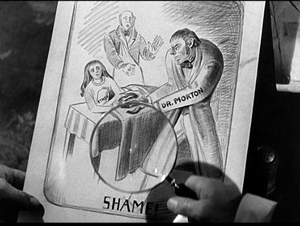

The plot’s true climax is Morton’s gesture of sacrifice. Sturges encourages us to see it as a contrast to the way the press and his profession vilified him. During the first flashback, a newspaper cartoon shows Morton preying on innocent patients, as typified by a girl on a gurney.

Sturges expected us, I think, to recall this image when Morton decides to help the girl. In his life, the cartoon came later, but showing it early in the film lets Morton’s gesture serve as a rebuke to those who are going to hound him.

After revealing Morton’s sacrifice, Great without Glory provides a bitter epilogue. The film ends with a return to the framing situation in Elizabeth’s parlor. Eben rises sadly, leaving Elizabeth alone.

Sturges could simply have built his film around Morton’s early life and his successful discovery, ending before the decades of poverty that followed. Instead, by focusing his biopic around our failure to appreciate and reward selfless research, he wanted to praise a man who achieved greatness but not the long-lived veneration accorded Edison or Pasteur. Yet showing Morton’s fall from grace after the crowd’s acclaim meant that the high point of a science biopic would be accomplished far too early in the plot. What we today call the “darkest moment”—Morton’s rejection by his public and his poverty—would come too soon. When Sturges showed his cut to his friend John Seitz, a great cinematographer, Seitz asked: “Why did you end the picture in the second act?”

According to Sturges, Buddy DeSylva said the same thing. He was already hostile to Sturges, and after some mixed preview results he set about reshaping the picture. The result is a good example, I think, of unintended innovation.

DeSylva did, as Sturges indicated, “leave out the bitter side” in certain respects. He lopped off the final scene showing the mourning of Eben and Elizabeth. The Great Moment doesn’t return to the narrating frame set up from the start of the picture. This is a little disconcerting structurally, but it wasn’t unknown at the period. Guest in the House (1944), Dillinger (1945), and other films “forget” the fact that they began with a character recalling the past.

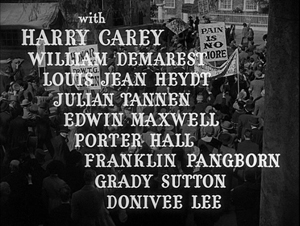

Nor did DeSylva start the plot with Sturges’ prologue and narrating frame. He offered something immediately upbeat: Morton and Eben descending to the cheering crowd and riding through the streets to acclaim. This action, surprisingly, takes place during the credit sequence.

By inserting the moment of Morton’s triumph at the very start of the movie, before we have even seen a flashback to it, or indeed even know who these people are, DeSylva seems to illustrate the film’s title. Our first impression is that Morton’s great moment is the public recognition of what the crowds’ placards announce is his conquest of pain.

Only after this “flashforward” does the release version settle down to something roughly like Sturges’ structure. Eben discovers the medal, brings it to Elizabeth, and elicits her recollections. Some of the scenes are rearranged from Sturges’ version; the placement of one, showing Morton sick in bed, seems calculated to lead in to his death (as it doesn’t in the Sturges cut). The newspaper cartoon is there, ready to form a parallel with the climax. As in the Sturges version, a return to the narrating frame shows Eben and Elizabeth in the present launching the second big flashback. With other alterations, we go through the couple’s romance and marriage, culminating in the discovery of ether and the prosperity of Morton’s practice.

DeSylva retains Sturges’ climax: the scene when Morton must choose whether or not to reveal his trade secret to his competitors in the public demonstration. Seeing the girl praying on the gurney, he decides to do it. The film ends with him striding into the operating theatre, about to share his discovery. It is here that DeSylva halts the film, without, as we’ve seen, returning to the frame featuring Eben and Elizabeth.

Both locally and more broadly, the effect is curious. Now Morton’s great moment is revealed, as Sturges wished, as the moment of his self-sacrifice, not the moment of his celebrity. But more strangely, without the final frame situation, the film ends just before the opening credits sequence. We could easily imagine the credits as an epilogue, with Morton’s entry to his colleagues dissolving to the parade in his honor before the final fade-out. Instead, the film halts and wraps back around itself like a Möbius strip: the last thing we see immediately precedes the first thing we saw.

I’m not trying to make this movie Memento or Primer, but there is something uncanny about the release cut’s looped structure. Sturges created a story that was depressing but tidy (prologue, carefully framed flashbacks, epilogue). DeSylva, unable to rewrite Morton’s history and apparently reluctant to junk the project, made the story more upbeat but also more untidy. Trapped by Sturges’ design, he re-carved it in a uniquely peculiar shape.

Sturges’ bold stroke was to switch the two chronological blocks of Morton’s life and to make us sense the injustice of Morton’s fleeting fame. DeSylva wanted to avoid the grim epilogue in the present and end on an upbeat note. But he did retain the split chronology, so that the contrast between obscurity and fame remains. He inadvertently innovated by making the opening credits preview a scene far ahead in the plot, and then letting the ending twist back to it. By playing the title over the parade, the release version shifts us across two moments, and meanings, of greatness: celebrity and self-sacrifice.

Did Buddy set out to be daring? I don’t think so. He faced constrained solutions whichever way he turned, just like us most of the time. More on this matter at the end.

As easy as C-A-C-B-C-B-C

As I mentioned, flashbacks usually sit comfortably in a frame, a well-established present situation that we depart from and return to. The shifts in and out of the past can be eased by various devices, one of which is a voice-over representing the character. The voice-over may be objective, as when a trial witness is testifying, or subjective, representing the “inner voice” of the person remembering what we have in the flashback.

Again, however, a film built out of flashbacks has many options. Coming to direction in the mid-1940s, Joseph L. Mankiewicz was in a position to try his own riffs on current experiments in storytelling.

So, for instance, in House of Strangers (1949), he frames a flashback without a voice-over. The camera coasts up a stairway to a window at night; dissolve to the window in daytime, and pull away to reveal the earlier scene. Our understanding of the time shift is aided by the comparison on the musical track: a phonograph record of a passage from the opera Martha fades out, and in the flashback, the Monetti family patriarch, now alive, is singing it.

Similarly, A Letter to Three Wives (1949) supplies the symmetrical structure in shifting from Deborah to her anxious memories and then back again.

But the voice-over varies from the usual. Instead of hearing her voice asking herself, “Is it Brad?” we hear the voice of Addie Joss, who also narrates the film. The suburban wives’ obsession with their rival, who may have run off with one husband, has allowed her to burrow into each woman’s consciousness. (In addition, her voice merges with the chugging of the ship to create distortions courtesy of Sonovox.)

House of Strangers is built around one long flashback; A Letter to Three Wives gives us three parallel ones. All About Eve yields yet another variant. Three characters at a banquet recall their experiences with Eve, the dazzling young actress to be given an award. There will be several flashbacks following Eve’s career chronologically and skipping from one remembering character to another. Given this plan, Mankiewicz’s long version planned for one moderate experiment and one fairly daring one.

The moderate experiment was to eventually eliminate the visual anchoring of the frames. He had planned to start with very clear bookends around the flashbacks and then gradually discard framing scenes. For instance, after Addison DeWitt’s voice-over introduces the other characters, including Margo and Karen sitting at his table, Karen’s voice-over intervenes. We leave the banquet to flash back to her meeting Eve.

In Mankiewicz’s “shooting draft” of the film, we then return to the banquet in the standard bookend fashion. Karen looks over at Margo much as Addison had looked at her. We hear Margo’s voice-over, and then her flashback is launched. Mankiewicz planned, in all, three of these base-touching intervals in the banquet. The later flashbacks are simply signaled by voice-overs only, interweaving the memories of Karen, Margo, and Addison as Eve rises in the theatre world. In short, Mankiewicz wanted to replace block flashbacks with “polyphonic” ones, but only after careful preparation.

The more daring experiment, and the one whose loss rankled for years, was the idea of replaying Eve’s famous “applause” monologue. We’re at Margo’s party, and several characters are perched informally on the staircase. Addison and Bill, Eve’s fiancé, have argued about the nature of the theatre. Then Eve launches on a brief but impassioned ode to the joys of acting. Applause amounts to “waves of love coming across the footlights and wrapping you up.” Mankiewicz wanted this to follow a scene between Karen and Eve in Margo’s bedroom. Introduced by Karen’s voice-over, this scene shows Eve pressing Karen to help her become Margo’s understudy. Following this, Eve’s monologue can be seen as a warm testimony to her dedication to the theatre—a confession that Karen watches dotingly from a higher step.

At this point, Margo enters from the kitchen and confronts Eve before insulting the other guests and flouncing off to bed.

Instead of showing this scene’s aftermath, Mankiewicz wanted to break chronology and skip back to the beginning of the party, with Margo’s voice-over now introducing things. After some scenes showing her efforts to get Eve out of her life, she was to stalk out of the kitchen and hear in the hallway the end of Eve’s monologue.

They [Margo and Lloyd] exit into the dining room. As they open the swinging door, the CAMERA REMAINS in the doorway. Margo and Lloyd walk toward the stairs. In the b.g., Eve is talking to the group.

How much she says is dependent on how long it takes Margo and Lloyd to reach her.

EVE (in the b.g.): Imagine,,, to know, every night, that different hundreds of people love you… They smile, their eyes shine—you’ve pleased them, they want you, you belong. Anything’s worth that.

Just as before, she becomes aware of Margo’s approach with Lloyd. She scrambles to her feet….

MARGO: Don’t get up. And please stop acting as if I were the queen mother.

And as Margo speaks—or before—we FADE OUT.

By following Margo’s efforts to cast Eve out, the effect of hearing part of the monologue is to confirm Margo’s suspicions that Eve’s demure obedience conceals her desire to compete on the stage.

What Mankiewicz wanted, it seems, was to use a replay for a new purpose. In Mildred Pierce and other 1940s films, the replaying of an action fills in missing material, usually with the purpose of dispelling a mystery or providing a surprise. Here the replay contrasts two characters’ reactions: Karen finds Eve’s speech touching, Margo finds it threatening. Most replays enhanced plot, whereas this emphasized characterization (which in turn advanced the plot).

Or might have. Zanuck, as we saw, cut it out. The incisions left some little scars, as you can see from the discontinuities in the final version. Eve, her trance broken, glances up and sets her expression into standard Alert-and-Deferential Eve mode, as if Margo were coming right at her. Then she gets to her feet. All this apparently happens well before Margo rounds the corner of the doorway.

So Zanuck eliminated Mankiewicz’s boldest step. But, in a reciprocal movement, he found Mankiewicz’s flashback anchorings over-cautious. Zanuck’s version simply cut out all the returns to the banquet except for the very last one.

One consequence is to give greater saliency to the final portion of the banquet ceremony, which has been halted, as if by magic, during Addison’s address to us. Other effects of Zanuck’s excisions waft through the whole film. The floating voice-overs that Mankiewicz had painstakingly prepared (according to the Rule of Three) now emerge at the very start. Voices slip in and out of scenes, more or less tied to what each speaker could have known at that point but never given the sharp boundaries of the standard blocked-and-framed flashbacks.

These floating voice-overs point ahead to the freedom our filmmakers have enjoyed since the 1990s. We no longer demand that explanatory voice-overs be anchored in any Now; they can braid together as ongoing commentaries on the action. From Hollywood to Wong Kar-wai, filmmakers take for granted that they can discard bookended narration in the way Zanuck did. Mankiewicz objected to Zanuck’s habit of cutting scenes “from peak to peak to peak.” But the boss, who always liked his movies fast-paced, explained: “I am way ahead of you and so will the audience be.”

The choice cascade

There’s a lot more to be said about these films and filmmakers, and I hope to develop some of those ideas in my book. For now, there are some interesting lessons.

First, in filmmaking, once you’ve made certain choices, others follow and some become forced on you. What historians of technology call “path dependence” comes into play. Just as computers use fundamentally the same QWERTY keyboard that came into being with early typewriters, initial choices about a project set limits to what you can do. A trajectory makes certain outcomes more likely than others, and it’s hard to reverse.

Once Paramount committed to releasing some version of Sturges’ Pain project, DeSylva had to work with the split chronology somehow. But Hollywood tradition demanded an uplifting ending, so one had to be salvaged, even if that meant snipping off the return to the frame story. Similarly, once Mankiewicz commits to presenting Eve’s ascent from the perspective of three outside observers, certain narrational processes didn’t need as much redundancy as he loaded in. Likewise, Mankiewicz’s prized replay didn’t create path dependency. It was a branch off the main line and could, as Zanuck saw, be lopped off.

Second, in a routinized film industry, we ought to expect that conflicting demands and changes of plan will yield not only well-wrought plots and narration, but also partial, fractured, even discordant narrative patterns. Snafus and compromises are part of the process.

Finally, film techniques seem innovative only in relation to the norms of a period. Most of the narrative strategies employed by Sturges, DeSylva, Mankiewicz, and Zanuck would have probably seemed startling in the 1930s. By the 1940s, such experiments seemed fresh but comfortable additions to a growing repertoire of storytelling techniques. The studios’ solutions were feasible because some flexibility had already emerged in handling frame stories and voice-over transitions.

The history of film forms springs from creative choices made by individuals within institutions. Those decisions have consequences, intended or not. Sometimes the producers don’t suffocate new things; sometimes they create them. If only by accident.

Don’t worry, though. I won’t be making such arguments about The Magnificent Ambersons.

Daniel Mainwaring mentions his plans for Out of the Past in Backstory 2: Interviews with Screenwriters of the 1940s and 1950s, ed. Patrick McGilligan (University of California Press, 1988), 199.

On A Letter to Three Wives, my comparison of Caspary’s adaptation with Mankiewicz’s shooting script was enabled by the Caspary collection at the Wisconsin State Historical Society. Thanks to Mary Huelsbeck and the staff of the SHS for helping me access Caspary’s papers. Mankiewicz’s remarks about the process and Zanuck’s request to delete one wife are quoted from Robert Coughlan, “15 Authors in Search of a Character Named Joseph L. Mankiewicz,” a 1951 Life magazine article available in Joseph Mankiewicz Interviews, ed. Brian Daugh (University Press, of Mississippi Press, 2003), 17. Caspary was inclined toward modular plotting, as is shown in detail in A. B. Emrys’ Wilkie Collins, Vera Caspary and the Evolution of the Casebook Novel (McFarland, 2011).

Brian Henderson provides painstaking comparisons among various versions of Sturges’ scripts and the final version of The Great Moment in Four More Screenplays by Preston Sturges (University of California Press, 1995), 241-360. My quotations from Sturges come from James Curtis, Between Flops: A Biography of Preston Sturges (Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1982), pp. 171-172. Another robust biography is Diane Jacobs, Christmas in July: The Life and Art of Preston Sturges (University of California Press, 1994). Essential as well is the autobiography Preston Sturges by Preston Sturges, ed. Sandy Sturges (Simon & Schuster, 1990).

Mankiewicz’s “shooting draft” of All About Eve has never, to my knowledge, been published. It is available on the Internet, God knows how, here. My extract is from p. 74. A screenplay closer to the finished film was published in 1951 by Random House. It is reprinted in More About All About Eve: A Colloquy by Gary Carey with Joseph L. Mankiewicz (Random House, 1972). Mankiewicz’s regrets over Zanuck’s deleting the replay are expressed in Andrew Sarris, “Mankiewicz of the Movies [1970],” in Dauth’s Mankiewicz Interviews, 31. The characterization of Zanuck’s “peak to peak to peak” cutting can be found in Sam Stagg, All About “All About Eve” (St. Martin’s, 2001), 171. Zanuck’s remarks about being ahead of his director’s screenplay are quoted in Mel Gussow, “The Lasting Allure of ‘All About Eve,'” New York Times (1 October 2000), AR13.

Two lively and careful critical studies are Kenneth L. Geist, Pictures Will Talk: The Life and Films of Joseph L. Mankiewicz (Scribners, 1978) and Bernard F. Dick, Joseph L. Mankiewicz (Twayne, 1983). Charyl Bray Lower and R. Barton Palmer’s Joseph L. Mankiewicz (McFarland, 2001) is an indispensable guide to the director’s work and writings about it. Both Sturges and Mankiewicz are discussed with polemical relish in Richard Corliss, Talking Pictures:Screenwriters in the American Cinema (Penguin, 1995).

I’m grateful to Laura Russo and particularly John C. Johnson of the Howard Gotlieb Archival Research Center of Boston University. Mr. Johnson kindly supplied valuable information about the version of the All About Eve screenplay held in the Bette Davis collection there.

Another case of the suits’ laying down demands to which a director responds creatively involves the final shot in Bill Forsyth’s wonderful Local Hero. Details here.

Finally, this entry is one in a series of spinoffs of my ongoing work on narrative in 1940s and early 1950s Hollywood. A gathering point for related blog entries is here, and a relevant web essay is here. As a coda to these 1940s films, it’s worth noting that in The Barefoot Contessa (1954) Mankiewicz did get to mount a replayed flashback scene, and in the 1960s he prepared a screenplay of Lawrence Durrell’s Alexandria Quartet that would have presented several characters’ perspectives on the central action.

All About Eve.