Archive for March 2014

Dispatch from another 35mm outpost. With cats.

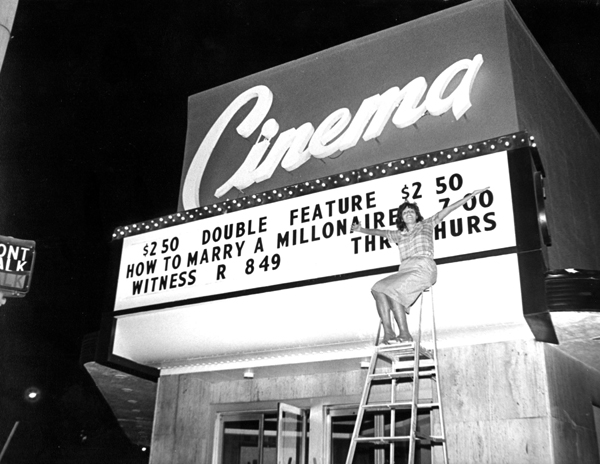

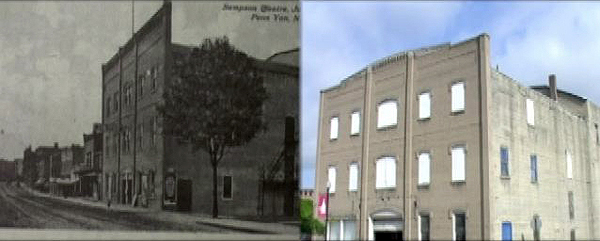

Cinema Theater, 1985, with JoAnn Morreale.

DB here:

For a while now I’ve been tracking the consolidation of digital cinema. After a blog series, I melded the entries with other information and created the e-book Pandora’s Digital Box. (To the readers who bought it, thanks!) Last year, in a blog called “End Times” I updated the information. Now we’re at post-End Times, I suppose.

David Hancock, who keeps meticulous account of these things, issued an IHS Technology Profile report on the state of things at end 2013.

*Of the world’s nearly 129,000 screens, over 112, 000, or 87%, are digital in some format. Most screens are compliant with the Digital Cinema Initiative standard used in the US, but India has pioneered the cheaper “electronic cinema” formats. Many of these e-screens will upgrade to the DCI standard.

*The UK and France have fully converted, along with most smaller European countries. Those countries benefited from various degrees of government support for the conversion.

*China now contains over half of the 32,642 digital screens in Asia.

*High concentrations of 35mm venues remain in Egypt, Morocco, Greece, Portugal, Ireland, and other areas with economic troubles. Other analog countries, such as Slovakia and Slovenia, lack public funding and contain mostly single-screen venues. The more multiplexes a country has, the greater the pressure to go DCI.

*In North America, out of about 40,000 screens, close to 93% have converted. That leaves about 3200 analog venues. It’s hard to know how many of those have closed or will close soon.

Most of the surviving analog sites, I suspect, are subsequent-run, like the five 35mm screens at our Landmark/Silver Cinemas ‘plex. And our Cinematheque and student-run Marquee continue to find and show excellent film prints. But clearly the moving finger has written. We at the University are striving for funding to make the changeover.

So too is a wonderful cinema I visited back in January. A family trip carried me back to my stomping grounds in New York’s Finger Lakes. I’ve already retailed some information about my hometown cinema, and a 1915 film that was discovered there. For now, let me tell you about a theatre I visited during a few days in Rochester.

Let George do it

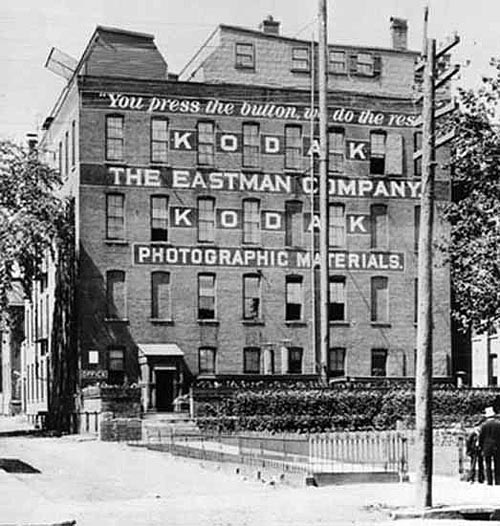

Eastman Company, 1892.

Before there was Hollywood film production there was New York film production. Before that, there was West Orange, New Jersey, where Mr. Edison and Mr. Dickson devised a movie machine. And somewhat before that, before movies themselves, there was Rochester.

Rochester was the home of the George Eastman company, founded in 1880. Eastman pioneered consumer still photography; he made up the word “kodak” to suggest the click of the shutter button. The company manufactured the flexible 35m film stock that formed the basis of the American cinema industry. Another Rochester industry, the venerable Bausch & Lomb provided camera and projector lenses, including those for CinemaScope in the 1950s.

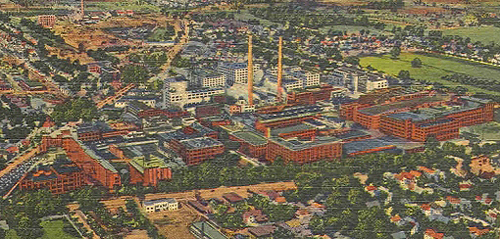

I suppose most people under thirty have never used a film-based camera, and for them the firm’s cheery yellow-and-red logo looks the way an ad for Packards looked to me in my teen years. Throughout most of the twentieth century, though, Eastman Kodak was one of America’s great technology firms. Here’s the Kodak Park facility ca. 1940.

The firm’s tragic decline will eventually get book-length treatments, but a short version is here.

Despite having invented the first digital camera, Kodak was overwhelmed by faster-moving competitors in that realm. As the firm mounted huge losses, the CEO, Antonio Perez, sought to leverage cash through Kodak’s many patents, but that tactic couldn’t stave off disaster. By 2011 Kodak stock was selling at about $1, down from the $25 it had been at when Perez arrived. In the same year, he was appointed to President Obama’s Council on Jobs and Competitiveness. Kodak filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy in the following year.

Kodak has tried to reinvent itself, but its collapse has damaged Rochester badly. Growing up, I encountered in Kodak a supreme example of paternalistic capitalism; George Eastman even paid for dental care for all of Rochester’s children. In the 1980s over 60,000 people in Rochester worked at the firm; now fewer than 7,000 do. As the company imploded, its pension funds fell behind. During my stay I met former employees who had counted on a secure retirement and are now struggling to make ends meet. There were also plenty of salty epithets aimed at Perez, who is said to receive an annual salary of over $1 million, along with millions more in other compensation.

Some argue that Rochester as a whole is recovering. If so, it’s a slow climb.

Still, for cinephiles, Rochester remains a remarkable city. There is the historic Little Theater. It’s one of the oldest art houses in the country and now has several screens, all but one of them digital. The theatre has been taken over by the local NPR outlet and presents indie and foreign titles, along with some live music events. There’s also the magnificent Dryden Theatre operating under the auspices of the George Eastman House, one of the world’s great archives. Its programming has always been stellar, and it continues to bring rare films to the city.

Then there’s a real survivor: the Cinema Theater.

The South Wedge upstart

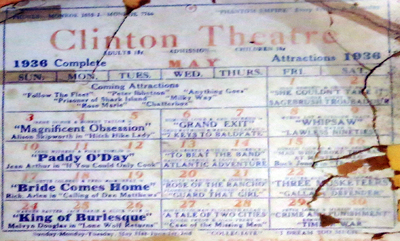

The Clinton Theatre, mid-1930s. The features are In Old Kentucky (1935) and The Return of Peter Grimm (1935).

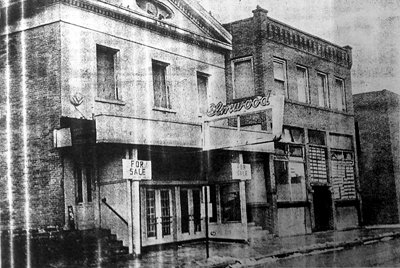

It opened in 1914, smack in that period when motion pictures became the movies. It was initially called the Clinton Theatre because it occupies the corner of South Clinton Avenue and South Goodman Street. It offered minimal comforts. Donovan A. Shilling, in his colorful and nostalgic Rochester’s Movie Mania, tells of wooden benches and a dirt floor.

Those amenities couldn’t easily compete with the offerings of the Clinton’s more splendid rivals.

There was, for instance, the Piccadilly, opened in 1916. Advertised as a million-dollar house, the Piccadilly was built with a grand stairway and an orchestra pit for a sixteen-piece ensemble. Its auditorium could seat 1500 people in what the trade press announced as exceptionally comfortable seats. A beautiful exterior photo is here. Eventually the Piccadilly became the Paramount. Rochester was a pretty rich city then.

The Clinton closed in 1916, reopened briefly, closed again, and reopened in 1918. This time it held on. Located outside the central theatre district, in a neighborhood known as South Wedge or Swillburgh, the Clinton was a classic neighborhood second-run house. You might have to wait quite a while to see a release, which would play the downtown theatres first. But at least you benefited from a swift turnover. During one week of February 1929, you could see The Big Killing and Bachelor’s Paradise (on a double bill), Uncle Tom’s Cabin, Tim McCoy in Wyoming, The Crowd, and While the City Sleeps, starring Lon Chaney. These titles had been released in spring and early fall of the previous year.

The Clinton wasn’t part of a chain, but it hung on through Hollywood’s biggest studio years. In 1934 it was one of thirty-two Rochester theatres, some of them huge. The Century could hold 2500 people, the RKO Palace 3000. (Of course many such theatres hosted live shows as well.) With capacity of only 500 (about the same as the Little), the Clinton was in the same category as the Aster, the Broad, the Empress, the Hudson, the Lyric, the Majestic, and the Rexy. Admission was typically $.15, and that usually got you two pictures. Bills changed three times a week, with the big pictures running three days.

Surprisingly by our standards, the major films weren’t playing Friday and Saturday. I can’t prove this, but I’ve read that Sunday afternoons and evenings yielded the big audiences for neighborhood theatres–possibly because many people worked six-day weeks. (See the codicil for more information.)

But, as mentioned in an earlier entry, the late 1940s were problematic for exhibitors because attendance plummeted. In 1949, the Clinton was taken over by Jo-Mor Enterprises, a major Rochester chain. Renovated with the Art Deco façade it now has, the newly named Cinema played arthouse fare as well as subsequent-run Hollywood films.

The Cinema was headed for closure in the mid-1980s when it was saved by an unlikely heroine. Earth Science teacher JoAnn Morreale bought it and spent over $100,000 in improvements. She did everything from negotiating with distributors to cleaning toilets.

Her energy made the theatre what it had been in its heyday, a center for community activity. Locals came in with gifts and home-made treats. Some spent the day there, watching the double-feature matinee and the double-feature evening show. Six bucks got you four movies. Here’s the old beauty in 1992.

Two years ago the Cinema was bought by John Trickey. The house is still a second-run venue, but unlike most it still offers double bills. The night I visited with my sister Diane you could have seen Mandela and Gravity in one go. The prices have gone up only a little since the 1980s: $5 for adults, $3 for seniors, students, and kids under 12.

We met the Cinema’s majordomo Benjamin Tucker. By day Ben is a Curatorial Assistant at Eastman House, but he loves film history and is happy to help out the theatre.

The shows are still in 35mm, although Ben is coordinating a crowdfunding campaign to help out digital conversion.

Princesses

We met the staff, including the projectionists and the ticket lady Pat Russo, who has worked there for about ten years. She gives you real pasteboard tickets, not those flimsy, curly multiplex printouts.

And there’s the proud lineage of Cinema Theater cats, starting with Princess to Princess the second (ruling for about fifteen years) up to Sue, who’s been in residence about six months.

The Princesses would circulate among the seats, startling patrons by rubbing up against their legs or leaping onto their laps. Sue has a habit of settling down for a snooze in the middle of the line at the concession stand, forcing customers to step over her on their way to the popcorn.

I never visited the Cinema in my salad days (the 1960s). It wasn’t playing so much arthouse fare, I think, so I tended to visit the Little or the Dryden. I wish I had sought out the Cinema. This is one of the oldest continuously operating theatres in the country. Long may it flourish.

Thanks to Ben Tucker for information and images, to Jim Healy for tipping me off to the theatre, and to Diane and Darlene Bordwell for their company.

The image of the mid-1930s Clinton comes from Shilling’s Rochester’s Movie Mania; Carl Baxter supplied the original photo. More Clinton/Cinema Theatre memories here. The Rochester Subway site hosts stupendous, recently discovered photos of the RKO and Loew’s picture palaces.

PS 16 March 2014: Alert reader Andrea Comiskey supplies some background on the Clinton’s scheduling three programs per week during the classic years.

Mae Huettig (Economic Control of the Motion Picture Industry, 1944) says that only theaters that did not have to block-book (majors’ affiliates, members of large chains, etc.) got to choose films’ playdates. Whether this was really as absolute as she makes it sound, who knows? But what this means for when the “best films” (typically the A pictures) would tend to appear is tough to determine. On the one hand, you could imagine that distributors would want the strongest, most appealing films showing on the weekends when they could bring in the biggest crowds. On the other hand, you could imagine distributors trying to force underperforming/weaker films onto bills on the busier days since there’d be higher baseline business regardless of the merits of the films on the program. Exhibitors that didn’t get to pick playdates certainly did complain.

In an interview published in Kings of the B’s, (1975) Monogram’s Steve Broidy says that Saturday is the busiest day, at least for small-town exhibs. He also says that these exhibs liked flat-rate rentals on Saturdays so they could run up the profits and echoes the idea that the particular film didn’t matter a ton since people were going out to the movies regardless.

As was the case with your Rochester example, theaters that changed programs 2 or more times a week (which, at least in big cities, were more likely to be sub-run houses) often split the weekend days across two programs, with many theaters adding an extra feature exclusively for the Saturday kiddie matinee. I’ve seen just about every possible permutation, but for a twice-weekly changeover, Sun-Wed & Thurs-Sat was a pretty common pattern. For thrice-weekly, Sun-Tues, Wed-Thurs, & Fri-Sat was common. But I’ve also got plenty of examples of theaters that showed the same program Sat. & Sun.

Andrea is writing a dissertation about distribution and playdate patterns in the 1930s. I’m happy to get her clarification here, which shows, as usual, that film history is always more complicated than it seems at first.

The Cinema, 2014. Photograph by Darlene Bordwell.

You can go home again, and maybe find an old movie

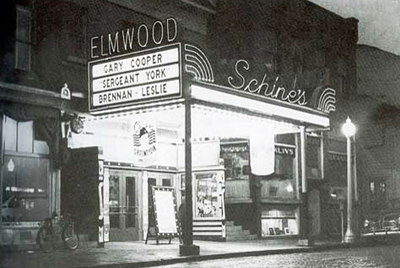

Schine’s Elmwood Theatre, Penn Yan, New York, late 1954-early 1955. Photo courtesy Yates County History Center.

DB here:

Nowadays when a theatre closes or goes digital, it says farewell by screening The Last Picture Show. That hadn’t yet become a tradition when the Elmwood Theatre of Penn Yan, New York presented Bogdanovich’s movie on its final day in November 1972.

Six people showed up.

The Elmwood had been going downhill for years. “I think the theatre building is an eyesore,” declared the chairman of the town’s Urban Renewal Agency. Once part of the powerful Schine circuit, the theatre had been acquired in the mid-1960s by the Rochester-based Panther chain, later renamed Countrywide. That firm seems to have specialized in low-budget genres and X-rated fare. In Penn Yan, the UR officer declared, most of the Elmwood’s programs were rated “restricted,” adding: “Yet it is claimed by some that it is a recreational facility for our children.” Disney films were screened at the Elmwood during those years, but local moviegoer Robert Brainard noted: “They were getting all the junk and nobody was going, not even the kids.”

When the theatre was finally closed, it stood vacant. Vandals broke the windows, and pigeons roosted inside. It had come a long way from the 1940s.

In 1974, two businessmen paid $11,000 for the building and turned it into a racquet club. That business operated for some years, but in 2003 the entire structure was demolished and a new village hall was built on the site.

By then a small three-screen mall cinema had set up business elsewhere in town. I report on a visit here.

In January, I was back in Penn Yan and naturally I sniffed around. Thanks to John H. Potter and Lisa M. Harper of the Yates County History Center, and my sisters Diane and Darlene, I came away with some precious information about the theatre I attended for the first eighteen years of my life.

I also came away with an extremely rare film.

Broadway Melodies and Cherry Blossom Queens

Captain Harry Morse ran steamboat trips on Lake Keuka. He was a legendary figure. Some said that as a boy he had caught a lake trout on his nose. (I know: How could you do that? Supposedly he bent over the side of a boat and a trout leaped up and glommed on.) More prosaically, Morse invested in Penn Yan movie houses, and in 1920 he bought the Shearman House Hotel, a popular stopover for visiting vaudevillians. Morse turned the Shearman House into a theatre.

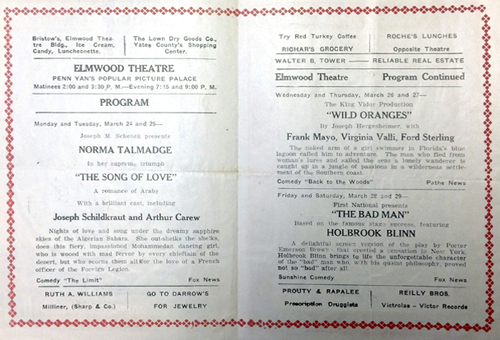

The Elmwood Theatre opened in 1921. It held at least 700 people. That’s pretty big for a town of 4500 people, but as the county seat and a business center, Penn Yan brought in farm families. Many shows were accompanied by printed programs listing coming attractions and carrying advertisements for local businesses. This one, for Song of Love, is from 1923.

Admission was typically 11 cents for matinees and 17 cents for evenings. “Specials” like Chaplin’s The Kid boosted ticket prices to 17 and 28 cents. In 1936 the Schine chain acquired the house.

The Elmwood benefited from the projection expertise of Nathaniel P. “Nat” Sackett. Nat had begun his film career in 1908 at another local movie house, vocalizing with the song slides shown between reels. He became a projectionist before joining the Elmwood in 1923. He stayed on for several decades. According to Nat, The Broadway Melody was the first sound film the Elmwood played. During World War II, he worried that too many theatres were running triple features. If the fad continued, production couldn’t keep up. For Penn Yan, one feature was good enough—especially if it was something like How Green Was My Valley or Captains of the Clouds.

A small-town movie house often became a community center. Elmwood patrons remember talent shows and holiday parties, with gifts and contests before the screenings. In 1940 a housewife attending I Love You Again could join an hour-long cooking class (with prizes) just before the show. Young women would be named Apple Blossom Queen or Cherry Blossom Queen. Halloween screenings included costume contests and of course sudden blackouts and scary sound effects. During the war, with no television or Internet, people flocked to the theatre for newsreels. Customers were steered in and out by ushers; the Elmwood employed them well into the 1950s.

“Today,” remembered Nancy Gillette, “most people cannot imagine a theatre as large as the Elmwood, which included a large balcony, being full most of the time.” By the 1930s, admission prices had come down a bit for children. Ten cents admitted Nancy to the Saturday marathon matinees: “Gene Autry, Hopalong Cassidy, Roy Rogers, Charlie Chan, the newsreel and one or two cartoons—WOW!” Lines of kids stretched down the block. In the 1950s, Diane and I were among them, watching the same cowboy heroes, along with Tarzan and Martin and Lewis.

Romances and marriages were forged at the Elmwood. In 1933, a young man taking tickets let a young woman slip out to retrieve the keys she left in her car. Over the next few days he began to drive by her house. Her cousin knew the young man and said, “Margaret, I am taking you out when Sam comes along, and I’ll stop his car and introduce you to him.” After two years of dating, Margaret and Sam married and eventually had three children. The Elmwood manager gave Sam’s mother and Margaret free passes.

Local kids like Sam found good work at the theatre. Being an usher got you free movies and a chance to flirt with the concession girls and those who came “solo.” After movies there was pizza at the Den below the theatre. But among the ushers’ tasks was the very onerous one of changing the marquee. Jerry Nissen remembered:

First you had to do layout on paper what the marquee was to say. Then, working from the last letter in the last row, fill a heavy wooden box until you get to the first letter of the first row. The solid metal letters were stored in the basement and you hauled them up to the street. Now imagine, if you will, climbing a rickety old step ladder in the rain or snow and taking down the old message and then letter by letter placing the new message on the two-sided marquee. Brrrr, it used to get very cold. Also on occasion we were the targets of some nice vocal comments and snowballs coming from the T & C Tavern across the street.

DIY movies, 1915

Wheat and Tares (Penn Yan Film Corporation, 1915).

Penn Yan had theatres before the Elmwood went up. In the ‘00s and ‘10s Nat Sackett sang at Theatorum and another theatre, both owned by the Wickham brothers. For a time Nat took over ownership of them. Before Captain Morse built the Elmwood, he was showing movies at the old Sampson legitimate theatre, as well as in the Cornwell, located above a department store. The town apparently had four screens in 1911.

With so many films playing within a couple of blocks, it’s perhaps not surprising that a local businessman decided to make one of his own.

Edward R. Ramsey owned a local paper mill and a factory that manufactured electrical cable. The story goes that when Ramsey observed that Hollywood, California was buying a great deal of his cable, he decided to try moviemaking. Ramsey sold his cable plant and started the Penn Yan Film Corporation.

After making some shorts, Ramsey tied his first feature production to a fund-raising effort by Keuka College. The college’s aim was to provide advanced education to rural students who couldn’t to go to a big university. Ramsey’s film would demonstrate the virtues of going to college. All the talent was local, including the cameraman, who was Ramsey’s brother. From outside, Broadway actor and occasional film director George E. LeSoir was recruited to direct the show.

Shot in the summer of 1915, Wheat and Tares traces the story of two young men. Both Jim Watson and Will Beggs read dime novels, but Jim is encouraged by Alice Corwin, daughter of a Penn Yan businessman, to improve himself. Uplifted by literature, Jim leaves the farm for Keuka College. There he learns enough to become an auto salesman. At the same time, Will (who stuck to pulp fiction) falls in with a gang of layabouts and petty crooks. Their fates converge when Jim discovers oil. A crooked realtor hires Will to put Jim out of action long enough for the site option to expire. But Alice renews the option, and Jim’s family becomes rich. Meanwhile, Will’s life of crime catches up with him, and he is sentenced to a prison road gang. Jim and Alice, now married and with a child, stop when they see Will on the road. Jim vows to help his old friend go straight.

Despite its opening-night success at the Sampson playhouse, Wheat and Tares didn’t have legs. Keuka College closed in fall 1915 and didn’t reopen until 1921. Ed Ramsey died in an auto accident in June 1916. The film may have gotten no distribution outside the region. Stored in the Ramsey home, it was discovered decades later when the house was prepared for demolition. The film was transferred to safety stock and eventually to DVD. That’s the version I have seen.

In the moralizing manner of its day, the full title, Wheat and Tares: A Story of Two Boys who Tackle Life on Diverging Lines, contrasts the life paths of its two protagonists. A tare is a form of weed that infects a field of healthy wheat. Tares in their early stages look very much like wheat, so the metaphor implies that one must wait to see if a young man will turn out well or not. (The Biblical reference is a parable by Jesus, at Matthew 13: 34-35.)

The surviving copy of Wheat and Tares has lost its opening reel. What remains is a fairly ordinary 1915 film. The parallel stories of Jim and Will aren’t developed in tandem; we lose Will for most of the film. A great deal of the second reel is occupied with rich boys hazing Jim at college, which does teach him the manly art of self-defense, but to no special point: he doesn’t get to use his boxing skills later. Another undeveloped plot line involves a movie company filming in the vicinity.

Theme and plot don’t match very well. If you are trying to convince people that going to college will better them, why show your hero succeeding by stumbling onto an oil gusher? Jim would have been just as likely to find oil if he had stayed a sodbuster. The climax is particularly feeble: While Jim is recovering from the beating given him by Will and another thug, it’s Alice who saves the day. She does this not through extraordinary courage or sacrifice, but simply by having her father write a check that renews the option. The realtor, a very passive villain, does nothing, underhanded or otherwise, to block her maneuver.

Stylistically, you can hardly expect The Birth of a Nation, The Cheat, or Regeneration from this tiny Finger Lakes company. In most respects, the film resembles standard films of the period. Some filmmakers were exploiting the sort of crosscutting popularized by Griffith, but Ramsey and Le Soir take almost no advantage of it. There’s no fast cutting to pick up the pace. Most scenes are played in single shots, with close-ups used only to emphasize details, such as a deck of cards, that can’t be easily seen in the master framing. The closest shots of the principals occur during a phone conversation–again, a convention of the period.

Nor does the film exploit the sort of complicated staging we find in tableau cinema. There is one rather well-handled crowd shot, as well as a smooth track-in and-out when Will recruits a one-eyed thug to help him ambush Jim. Simple camera movements like this were by 1915 considered a fairly normal option.

There is an ambitious matte effect when Jim and his college chum Phil visit the movies, but even this fairly common device is somewhat bungled when the boys’ bodies become ghostly by crossing into the matte area.

Although Wheat and Tares exemplifies ordinary cinema of that day, like most films of the first great era of cinema it’s a pleasure to watch. Shooting on location yields spontaneous beauties. At one point Jim rides home on the trolley. In a film utterly lacking in calculated lighting effects, we get a lovely image. Not only do we see the town and wagons pass through windows, but after Will and his partner jump aboard, accidents of backlighting turn them into sinister shapes.

Trolley shots are among the glories of 1910s cinema; I don’t think I’ve ever seen a bad one.

Penn Yan must have been gorgeous then, with the main streets lined with elms.

The trees were felled by Dutch elm disease and other factors, I’m told.

As with any film shot in surroundings that you know, part of the fun comes in spotting familiar locales. John Creamer’s introduction juxtaposes some town landmarks. Here’s the Sampson Theatre, then and now.

Two locations that my sisters discovered pop up late in the film. For a chase, the camera was set up just around the corner from Ramsey’s house.

Ramsey’s house was demolished to add a building and a parking lot to the local hospital, but from that vantage point, we found the source of another shot. The camera was apparently set up in front of Ramsey’s home to frame Jim and Alice and their child in their chauffeur-driven Maxwell. The sidewalk in the foreground is gone, but the background area, including the fire hydrant, has stayed surprisingly constant.

And whatever the faults of Wheat and Tares, watching it gives you a glimpse of the entrance to Captain Morse’s Sampson Theatre (below). In the summer of 1915, Charlie Chaplin had sauntered into my home town. The show starts on the sidewalk, as they used to say.

I’m grateful to John and Lisa of the Yates County History Center for all their suggestions, for access to their files, and for the exterior photo up top and the shot of the Elmwood interior. You can read the local newspaper’s announcement of the Wheat and Tares premiere, with a teaser synopsis, here. Thanks also, of course, to Darlene and Diane. The picture of Penn Yan’s town hall was supplied by Darlene, whose photography site is here.

A DVD copy of Wheat and Tares is available for $15 from the Yates County History Center. You can email Lisa M. Harper, ycghs at yatespastdotorg, or call (315) 536-7318. Credit cards accepted.

The indispensable guide to the theatres in this region is Norman O. Keim’s Our Movie Houses: A History of Film and Cinematic Innovation in Central New York (University of Syracuse Press, 2008). You can read about the Schine chain there, or here.

Wheat and Tares is a prime example of an orphan film. Dan Streible of NYU is a moving force behind retrieving and restoring these elusive items, and a new Orphan Film Symposium is coming up in Amsterdam.

Wheat and Tares (1915). The sign on Charlie’s crotch reads” “Meet Me at the Sampson Program.”

Somewhere it’s always GROUNDHOG DAY

Phil earns his groundhog halo.

Kristin here–

Back in 1999, my book Storytelling in the New Hollywood (Harvard University Press) was about to be published. It was an attempt to suggest that, contrary to the talk of “post-classical” or “post-Hollywood” norms having taken over American filmmaking, the most important classical principles that had been at work since the 1910s were still going strong.

I outlined those principles in the opening chapter, discussing character goals, deadlines, dialogue hooks, unity, and the like. I also argued that, based on my analysis of many films from the 1910s to the 1990s, the vast majority of features followed a structure involving four large-scale parts, or acts–not three, as the popular Syd Field model would have it.

To do that, I analyzed the techniques of ten films usually considered to be models of unified, sophisticated narrative structure: Tootsie, Back to the Future, The Silence of the Lambs, Groundhog Day, Desperately Seeking Susan, Amadeus, The Hunt for Red October, Parenthood, Alien, and Hannah and Her Sisters.

The book was not intended to be a screenplay manual as such, though I know it has been used in some classes and by some aspiring screenwriters.

Ordinarily the press would have asked me to name some prominent film scholars who could be asked to write blurbs for the cover. It occurred to me, though, that it might be better in this case to take each chapter and send it to its director and to its main screenwriter and ask them for blurbs instead.

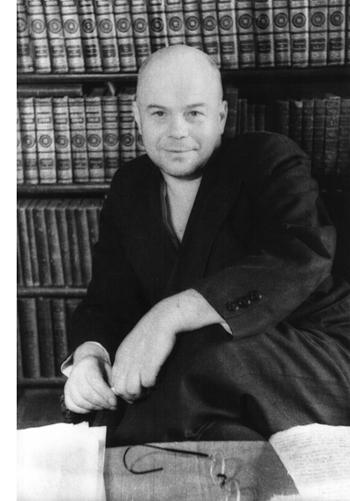

That turned out to work pretty well. Several didn’t answer, and other answered too late to be included. I ended up with three blurbs of which I am very proud, from Ted Tally for The Silence of the Lambs, Susan Seidelman for Desperately Seeking Susan, and from Harold Ramis for Groundhog Day.

Ramis’ recent death prompted me to dig out that old file. He had written back to my editor not with a sentence or two to use as a blurb, but with a page-and-a-half letter on the subject; it included a blurb down toward the bottom. It’s a letter that reflects how kind and smart Ramis was, and how much he had thought about writing and narrative–even though the process of writing screenplays was probably largely an intuitive one. It shows that he knew something about academic film studies, even if he had some “quibbles” with them. I certainly never meant to suggest that everything I pointed out in the films I analyzed was intended by the director and/or screenwriter. I would say that everything I pointed out was a result of their skill and experience. Even when something happens by accident during filming, someone has to decide whether or not to keep it in.

Rather than just sticking the letter back in the file, I thought I would share it with you. Having a little more of Ramis available can’t be a bad thing.

Dear Lindsay,

Thanks for sending the chapters of Kristin Thompson’s book Storytelling in the New Hollywood and please convey my thanks to Ms. Thompson for including Groundhog Day among the “modern classics.” My only quibble with scholarly film analysis is the occasional tendency to read more significance into certain details than was actually intended, or to think that certain accidents of production, on-set discoveries, or improvisational dialogues were planned and scripted. I realize, from a Deconstructionist point of view, it hardly matters what I think anyway, so let me set aside my minor quibbles and congratulate Ms. Thompson on her new book. If you would, please pass this letter along to her.

I am not a student of screenwriting so I’m afraid I can’t comment intelligently on Ms. Thompson’s theoretical model. Certainly, the fact that most movies are about two hours long will determine to a large extent the length of the set-up, the placement of the crisis, the climax, and the denouement, but rather than look at films in terms of “acts,” I prefer to think in terms of “actions,” as if the narrative line were a string of pearls, dramatically linked, each taking the audience forward to the next point. If any particular action doesn’t advance the plot or contain some new information, it doesn’t belong in the narrative. As a writer I generally proceed more intuitively than structurally. As Ms. Thompson suggests, I suspect that most of us have simply absorbed the classical film structure during our formative years as members of the audience.

When I was hired to write my first Hollywood screenplay, Animal House, the producer handed my collaborators and I paperback copies of Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, and said, “This is what a good screenplay looks like. Just do that.” More than twenty years later, my only useful conclusion about structure is that nothing will work if you don’t have interesting characters and a good story to tell. One can argue for or against the three-action structure, but, whether or not there are consistent rules about the :well-made” screenplay, it’s already true that there are more well-constructed, formulaic screenplays than there are good ones. Also, one must always keep in mind that Hollywood films are almost invariably rewritten by additional (though not always credits) writers. One writer may be thought of as strong on structure, good for a solid first draft, another may be known for his dialogue, others for punching up action or comedy. Also , the Hollywood writer is always responding to script notes from studio executives, story departments, his producers, the director, and from his principal actors. In this convoluted and often tortured process, it’s sometimes impossible to attribute the final screenplay to the calculated intentions of one writer or team, and it’s often left up to a panel of Writers Guild arbiters to determine screen credit.

I didn’t intend to write such an inflated letter but there’s a lot to say on the subject and I have a considerable amount of experience.

If it’s useful to you, you may quote me as saying that Ms. Thompson’s insightful analysis of Groundhog Day and of the screenwriting process in general should be fascinating to both writers and audience alike. More thoughtful writing and more discerning audiences can’t help but lead to better movies, and this informative and provocative book is a step in that direction.

Best of luck on the publication of Storytelling in the New Hollywood and please feel free to contact me if you need any further comments.

Sincerely,

Harold Ramis

Harold Ramis as Allan “Crazy Legs” Hirschman (SCTV, “Indecent Exposure,” 1982).

Pulverizing plots: Into the woods with Sondheim, Shklovsky, and David O. Russell

American Hustle (2013).

The different writers, who live in different times, come across the same pattern, the same chain of circumstances, which reveal themselves in different ways in each time.

This is how plot travels through time.

Viktor Shkovsky, 1981

DB here:

Besides writing some fine tunes and cunning rhymes, Stephen Sondheim has been an audacious experimenter with storytelling on stage. Do you know Into the Woods? It’s a bittersweet mashup of fairytales. Instead of presenting each one separately, like the vignettes of Japanese history in Pacific Overtures, here Sondheim’s collaborator James Lapine has woven them into one elaborate super-story. Rapunzel turns out to be the sister of the baker who sells bread to Red Riding Hood to take to Grandma. The princes pursuing Cinderella and Rapunzel are brothers who eventually turn their affections to Snow White and Sleeping Beauty. And so on. It’s an ingenious contraption, and I look forward to the film version to be released this year.

Even before that, we can learn something useful from what Sondheim has done. In effect, he has offered us a nifty audiovisual aid for understanding some ideas about storytelling advanced by the Russian Viktor Shklovsky. Shklovsky is surely the most eccentric literary critic of the twentieth century. He is also one of the greatest.

Thanks to Maria Belodubrovskaya and web tsarina Meg Hamel, we’ve just posted the first English translation of a rare Shklovsky essay elsewhere on this site. Today I want to consider a couple of Shklovsky’s many provocative ideas.

All the reverses

Shklovsky wasn’t an ivory-tower aesthete. He fought in World War I, joined the 1917 February Revolution that overthrew the Tsar, and continued an army career. As a Social Revolutionary, he initially opposed the Bolsheviks and spent several years in hiding and in exile in Germany. In 1923 he returned to the USSR and settled in to work as a professional writer.

Abandoning university life (he never took his exams), he wrote countless journalistic essays and several film scripts for Soviet classics: By the Law (1926), Bed and Sofa (1927), The House on Trubnaya Square (1928), and the documentary Turksib (1929). His novels were experimental efforts, mixing memoirs with speculations on literature. Zoo, or Letters Not About Love (1923) subverts the form of the epistolary novel by including letters that are not to be read. (A red X crosses them out.)

Abandoning university life (he never took his exams), he wrote countless journalistic essays and several film scripts for Soviet classics: By the Law (1926), Bed and Sofa (1927), The House on Trubnaya Square (1928), and the documentary Turksib (1929). His novels were experimental efforts, mixing memoirs with speculations on literature. Zoo, or Letters Not About Love (1923) subverts the form of the epistolary novel by including letters that are not to be read. (A red X crosses them out.)

He became known for a porous, cryptic approach to writing. He can be repetitious, puzzling, tedious, and maddening; outlining one of his essays is a wrestling match. His jittery style mobilizes brief paragraphs, some consisting of a single short sentence, much as Eisenstein and other directors used short film shots: as a percussive device to assail the reader.

A quick phrase can swing into a digression, a tactic Shklovsky relied on even more as he advanced into his eighties. The man who thought Tristram Shandy was “the most typical novel in literature” had a soft spot for delay and detour. Some variations:

To take a break, I am inserting here a page from one of my old manuscripts.

After such an opening, one can digress in any direction.

Being the theorist of “baring the device,” Shklovsky naturally accentuates the artifice of his technique. “It’s not easy to enact a change of theme,” he says, doing it while talking about it. Later we get a hint of the arbitrariness of organization. “I’ll repeat–continuity can be started from any place.”

Shklovsky’s most enduring fame came through his association with what has become known as Russian Formalism. While studying at St. Petersburg, Shklovsky and some friends formed OPOYAZ, the “Society for the Study of Poetic Language.” They were convinced that the literary history they were being taught failed to get at the essence of “literariness”—the specific quality that made literature a distinct domain. Historians could compile names and dates, speculate on biographical influences and social pressures, but this still wouldn’t distinguish literary forms from non-literary ones. What makes a poem different from a grocery list, a courtroom drama different from a trial transcript?

In the late teens and early twenties, Shklovsky and his colleagues set forth a new approach to literature. That approach was called, by its enemies, “Formalism,” and the name has stuck.

In English, of course, the word has so many meanings that it should probably be retired. Sometimes it means studying “form” and neglecting “content”; that was part of what the Stalinist hacks meant when they insisted that Shklovsky & Co. weren’t advancing the class struggle by emphasizing ideology. Today, to use “formalism” as a slam is often to suggest something similar—that a formalist ignores “content” like race, class, gender, and nation. But the Formalists didn’t neglect content. What others considered content they treated as material that is shaped by the literary work.

Following up Formalist theory fully would take me far afield. Instead, I want to turn to Shklovsky for some thoughts on plot structure that are fairly different from those I floated here a little while ago. Consider it a fuller test drive than my entry from a while back discussing how Shklovskian theory helps us understand the evolution of John le Carré’s career.

Once upon a time

The Formalists were among the founders of “narratology,” the systematic study of storytelling. They gave us the foundational distinction between story and plot, or fabula and syuzhet. The fabula consists of the events in the story world as they’re arranged according to time, space, and causality. The syuzhet consists of the story events as we encounter them in the finished narrative. Flashbacks furnish the most obvious example of how plot structure rearranges story order. Sondheim’s Merrily We Roll Along is more unusual: its plot presents its story episodes in reverse order, so that the last thing we see is the earliest scene in the fabula.

My essay, “Three Dimensions of Film Narrative,” and the accompanying blog post on The Wolf of Wall Street, reflected my basic take on narrative analysis, which is holistic. I try to get a sense of the overall architecture, and see how particular elements slot into that. For instance, by suggesting that The Wolf has a five-part act structure, I traced a development from part to part as Jordan sets up his trading firm, conducts an affair that destroys his marriage, launches an IPO and attracts the attention of the Feds, expands his scheme to offshore money laundering, and eventually comes to ruin….and resurrection. My analysis traced action patterns that unfold like musical melodies through the movie.

Most people would defend a holistic approach in another way. The Wolf of Wall Street runs 173 minutes without credits. Its admirers argue that it needs to be so long because it has to accommodate all the plots and counterplots. True, maybe some scenes are a bit stretched (notably Jordan’s and Donnie’s hilarious Quaalude orgy), but on the whole Scorsese and his screenwriter Terence Winter could say that telling Jordan’s story adequately demanded a long running time.

Shklovsky asks us to think of storytelling less holistically, or at least to think of a different sort of whole. He takes us through the looking glass.

*Instead of treating a narrative as a linear chain of events—say, the adventures of an egoist like Jordan—let’s think of it as a point of intersection of various materials. Not a linear flow, but a collage of items brought in, trimmed, or discarded as needed.

*And instead of taking a narrative as determining the time it takes to unfold, let’s think of the time as determining the narrative. Think of the narrative as built to scale, with a predetermined size into which material has to be fitted.

Every knot was once straight rope

The Decameron (1971).

Shklovsky thinks that a narrative is like a collage because historically, short narratives aren’t cut-down long ones. Instead, long texts have been woven out of short ones. He and his colleagues were much influenced by studies in folklore, which showed that folktales were often built out of familiar pieces, or motifs. A motif might be a character, such as a jealous stepmother; an object, such as a magical ring; or an action, such as a test or competition. Storytellers could combine these motifs to create their plots. This is, on a big and self-conscious scale, what Sondheim has done in Into the Woods.

Shklovsky extends the idea of motif-assembly to the novel, which he claims grew out of collections of shorter stories. One example is The Golden Ass, an ancient Latin novel of the first or second century AD. In this tale a traveler undergoes some adventures but he also encounters characters who tell him their own stories. (Some of those may be based on folktales.) Similarly, the fourteenth-century Decameron of Boccacio consists of tales exchanged among ten characters sequestered to escape a plague in their city.

We have such story-collections in cinema, though they’re not common. Most obviously, Pasolini’s “Trilogy of Life” (The Decameron, The Canterbury Tales, The Arabian Nights) drew upon the tradition that Shklovsky is charting. A Hollywood example would be O. Henry’s Full House (1952).

Finding a pretext for assembling stories exemplifies what OPOYAZ called motivation. Motivation, as I’ve discussed here before, involves creating a justification for a formal choice. Motivation isn’t just for actors who figure out why a character behaves a certain way. It’s for every artist, as when a cinematographer tells of needing to “motivate” a pattern of light by providing a lamp or window.

More broadly, motivation gives the audience a reason to accept a formal option. One of my favorite examples comes in Citizen Kane. Having decided to tell Kane’s story in flashbacks more or less chronologically, Herman Mankiewicz and Orson Welles confronted a problem in their frame story. After Kane’s death a reporter would naturally turn to his surviving second wife before contacting friends or associates. But if Susan recounted her memories of Kane before the other witnesses did, her episodes would come from late in his life and throw off the chronology. Therefore the script makes Susan too drunk and angry to talk to the reporter Thompson when he calls. He must proceed to the Thatcher library, where he’ll learn about Kane’s earliest years. Later, when Susan is more sober, she recounts her flashback in its proper, chronological place.

Motivation is everywhere in cinema, and it assumes different guises. Sometimes filmmakers motivate their choices by realism. Susan, being an alcoholic, might well angrily refuse to talk to the reporter. Filmmakers also appeal to genre-driven factors, as when people sing and dance in a musical; presumably this will be the rationale for the musical numbers in the movie of Into the Woods, as they are in the play. Very often the motivation springs from what the plot demands. In a mystery, to keep viewers in the dark, you can attach the action to an investigator who gradually discovers what’s really going on.

Sometimes style needs motivation. In the recent vogue for first-person films like End of Watch, Chronicle, and the Paranormal Activity series, the makers find excuses for the characters to use their video cameras to record what’s happening.

Foreshadowing is a sort of motivation too. In The Wolf of Wall Street, Naomi’s aunt Emma comes to the couple’s wedding. In realistic terms, inviting a relative to the ceremony is plausible, but it’s there for structural reasons. The plot needs to introduce a character living overseas whom Jordan can later use to hold his smuggled money. This might seem a cold-hearted way to view a character, but the plot treats her just as heartlessly, killing her off at just the moment that precipitates a climax.

In sum, Shklovsky’s engineering approach prods us to ask why something is in this tale—not according to character psychology or thematic statement, but as part of a system of materials and their motivations. Perhaps Shklovsky thought he could motivate his late-period digressions by the reader’s knowledge of his age: the Grandpa Simpson alibi.

I’m in the wrong story

Wine of Youth (1924) publicity still.

How to motivate the sort of story-collections we started with? Minimally, you can create a framing situation in which one or more persons share a tale with an audience; that’s the Decameron solution. You can go further by making the tales seem to belong together. Perhaps they parallel one another, either explicitly or implicitly. One might prove that crime doesn’t pay, while another disproves it. Shklovsky calls this “a debate of stories.” In the 1924 film Wine of Youth, a young woman hears from her mother and grandmother about their courtships. The similarities and differences across the generations create comic parallels to the young woman’s own romance.

You could also motivate the connection between the frame story and the embedded ones. Shklovsky mentions that the very act of telling can slow down the action in the frame story, as when Scheherazade keeps narrating every night to postpone her death. Or perhaps a discovered manuscript (the embedded story) will have an impact on the people finding it. You might try to somehow blend the told story with the act of storytelling. In the British film Dead of Night (1945) the separate stories all involve fantastic events, and the people telling the tales stand outside them. But the film’s climax seems to turn the frame story itself into such a fantasy, creating a sort of Mobius strip that twists the film back to its beginning.

I think, though, the greatest power of Shklovsky’s idea comes with the notion that any big narrative is really composed of smaller ones. He goes beyond episodic assemblies like The Decameron and Dead of Night to suggest that even the most “organic” or tightly-designed plots can be considered well-disguised story collections. In other words, my holistic assumption is countered by one that treats a well-shaped whole as a heavily motivated collage of different stories. From Shklovsky’s perspective every narrative of any complexity is like Into the Woods.

We can imagine a continuum of the ways in which fairly distinct story lines are woven into one big one. You might bring the characters together in a single space, such as an inn. Cervantes used this tactic in Don Quixote, and the great Chinese filmmaker King Hu revived it in several of his films. Grand Hotel, Hotel Berlin, The VIPs, Nashville, and many other ensemble films gather different story lines within a single space and let them intertwine. Sondheim and Lapine brought their fairy-tale plots together in the same locale, the primeval woods. Often the linkage is one of time as well, with the action compressed into a few hours or days.

Given a unity of time and locale, we expect that the story lines will affect one another, which indeed happens in the films I’ve mentioned. This puts us in the land of what I’ve called “network narratives” and what Peter Parshall studies in his book Altman and After.

Apart from spatial connections and concentrated time connections, you can hook up your source-stories more tightly. Most complex narratives assign the characters roles in different story lines. For instance, Into the Woods ties its fairy-tale figures together by friendship, acquaintance, love, and kinship. Characters create goals that involve other characters. Rapunzel’s mother the witch demands ingredients for a potion, and these bring in Red Riding Hood, Jack and the Beanstalk, and Cinderella.

The implication is that every plot of any complexity, no matter how smoothly all its parts seem to fit together, is a paste-up, a virtual recombination of simpler action lines sewn together by motivations. A romantic comedy with a main couple and a secondary one? It’s essentially two separate plots joined by the simple strategy of making the couples friends with each other. The detective story in which various characters tell us their alibis? Separate plots hooked up by the need to involve them in the murder investigation. The heist movie that follows all the characters partnering in a single robbery? It compiles plots about different thieves and welds them together by a shared knockover.

Any path . . . so many worth exploring

For Shklovsky, even a novel’s protagonist can serve as a motivating device for connecting the various stories he or she encounters. “Gil Blas is not a human being at all. He is a thread, a tedious thread, by means of which all the episodes of the novel are woven together.” Likewise, in The Wolf of Wall Street, Jordan is not given a lot of depth. Some viewers have criticized this tactic, since he doesn’t change his attitude or ethical outlook, and seems to learn nothing from his rise and fall. Shklovsky could suggest that he’s chiefly a device for hooking together a string of episodes about the giddy high life of stock trading. Showing a weasel behaving like a weasel for three hours—some viewers have found him indeed “a tedious thread”—isn’t especially edifying in itself, but the film’s fascination comes chiefly from the escalation of excess we’re invited to witness.

From this angle, The Wolf of Wall Street somewhat resembles another current release, The Great Beauty. This film is more explicit in using the protagonist to combine plots that represent a cross-section of a society. We’ve had other films that use one character to survey, fresco-fashion, different milieus. Mizoguchi’s Life of Oharu is one such plot, and La Dolce Vita, to which The Great Beauty has often been compared, is another. Usually, though, the protagonist responds to what she or he encounters and changes as a result; in The Great Beauty Jep’s wanderings create a sort of ephiphany. Perhaps the novelty of the plot of The Wolf of Wall Street is that after being introduced to high-flying hedonism Jordan rushes in and never looks back.

Of course we could imagine other versions of The Wolf—an apprentice plot showing us Jordan learning the ropes at length from Mark Hanna, or a multiple-protagonist plot in which Donnie, Teresa, Naomi, and other characters get much more attention. Shklovsky reminds us of what screenwriters know instinctively: plot unity is often a matter of ruthlessly chopping out all those intriguing alternatives. Every complex tale is yanked and snipped out of a vast network of potential plots.

Consider American Hustle, much more of an ensemble piece than The Wolf. (Spoilers ahead.) I see it as a romantic comedy with a crime ingredient. Three principal love triangles are interlocked (Irving-Sydney-Rosalyn, Irving-Sidney-Richie, Irving-Rosalyn-Pete). These are pushed forward thanks to the doubled plotline characteristic of classical Hollywood cinema: work and love so intertwine so that the sting operation develops along with the romantic complications. David O. Russell and co-screenwriter Eric Warren Singer use many well-practiced comic conventions, including overheard conversations that precipitate crises. (As usual, no coincidence, no story.) In its unfolding American Hustle fits Kristin’s four-part-plus-epilogue model tidily.

In contrast to my perspective, Shklovsky invites us to consider how several conventional plots are squeezed into Russell’s film. Here are some.

*A husband has an affair with another woman, and his wife learns of it.

*A woman is a man’s mistress but another man is attracted to her. She leads both of them on.

*A con artist fleeces gullible people with the aid of a confederate.

*A dutiful father tries to protect his son from the mother, who’s a little crazy.

*A man betrays his friend and feels the need to confess it, even though it will ruin their friendship.

*A cop tries to bring down big-time crooks, against the wishes of his supervisor.

*A cop has captured a crook and wants to use that crook to get to higher-ups.

*A wife, feeling ignored by her husband, seeks the attention of other men.

*A man has a fiancée approved by his mother, but he’s attracted to a more glamorous woman.

*A small-time crook tries to scam the Mafia, and the gangsters learn of it.

*A father warns his sons against fishing on thin ice.

These plots are blended by having a few characters play multiple roles in them. Even in this profusion, by rewriting the film we could go further—say, expanding the conflict between the cop Richie and his mother, or going back further into Sydney’s past. As with The Wolf, by developing the sub-stories, we could multiply story threads forever.

Narrative can flourish like kudzu. What curtails things? Among other things, the second factor I mentioned at the outset: format.

Slotted spoons don’t hold much soup

Shklovsky suggests that very often a story is created (or re-created) in order to be of a certain size. Instead of the old saw “form follows function,” Shkovsky suggests another: form follows format. The length of the narrative is dictated in large part by the sort of thing it’s going to be. A pop song isn’t an operetta, a short story isn’t a novel, a miniature isn’t a mural.

At first glance this notion seems too stringent. Surely a poem or play can be any length we want. There are gigantic symphonies and sprawling picture scrolls. Whitman seems to have had no problem adding more and more poetry to editions of Leaves of Grass. But these instances might be exceptional.

There will always be outliers, especially among the avant-garde, but most storytellers work in media that set limits and favor certain lengths. At the moment, three hours is sort of a maximum for a Broadway musical play like Wicked, The Book of Mormon, or Spider-Man: Turn Off the Dark. It makes sense that, given high ticket prices, audiences want a reasonably extended experience. They get one in Into the Woods: it standardly runs about three hours, including intermission.

Even a big name like Sondheim works within time constraints. When he and James Lapine were contemplating redoing a fairy tale, they made a discovery.

Fairy tales, by nature, are short; the plots turn on a dime, there are few characters and even fewer complications. This problem is best demonstrated by every fairy-tale movie and TV show since Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, all of which pad the lean stories with songs and side-kicks and subplots, some of which are more involving than the interrupted story itself. And those are all less than two hours long.

They needed to expand their material to Broadway length, and they did it by recalling an idea they’d concocted long before—a TV show that brought together characters from other TV shows.

Shklovsky’s suggestion is particularly attractive to those of us who study media because most artworks in commercial formats fit basic dictates of size. . US network TV episodes run 22 minutes or 45 minutes. Novels have roomier boundaries, but editors still have their preferences. According to a publisher’s marketer, in 2010 the ideal novel ran between 80,000 and 110,000 words. The doorstops bestowed on us by Rowling, Martin, and Stephen King are the market-tested, lucrative exceptions.

As for films, we still have pretty strong constraints outside avant-garde and festival pieces like Sátántangó (seven hours). A-level feature films in the 1940s typically ran between 80 and 120 minutes; B-films were typically 60 to 80 minutes. The longest running times were reserved for roadshow specials like Gone with the Wind and Duel in the Sun. I don’t know of a systematic study of changes in running times, but today there’s still apparently a two-tiered system. Program pictures (horror, action, raunchy comedy) with unknowns or minor stars (e.g., Jason Statham) can run around 85-100 minutes, with credits. The big releases can run two hours or more, but seldom more than three. When asked why originally The Grandmaster was 130 minutes, Wong Kar-wai is said to have replied, “All movies are 130 minutes now.”

Granted, directors’ cuts and alternative editions offer some flexibility. An initial four-hour cut of The Wolf of Wall Street had to be chopped down to a little less than three, but the long version may show up on disc or VOD. For all I know, it could become a mini-series. But even then its installments will be constrained by the running times of that format. And my other main example today, American Hustle, fits Wong’s point: Without credits, it runs 130:30.

Only three more tries

Lion King 1 1/2 (2004).

How is the format’s scale connected to Shklovsky’s idea about building your narrative out of pieces? This way: You find or create the pieces that will fill out the narrative to a conventional size. The format helps you decide how much to add or take away from the ongoing collage you’re creating of characters, actions, and story lines. Again it’s a matter of motivation, finding ways of justifying what you want to keep in or leave out.

Within the overall size of the piece, there are smaller chunks that need to be filled. A recent example is Anchorman 2.5, in which new gags replace old ones but still must be squeezed into the original scenes. Today’s screenwriting manuals, with their insistence on something big happening on certain pages, also indicate how storytellers are encouraged to invent material to be fitted into a fixed frame. Some people hate the idea of a “formulaic” screenplay, but Shklovsky the pragmatist would, I think, compare it to verse forms like the sonnet and the haiku, which dictate quite specific slots to be filled. In this respect, Kristin’s multi-part model of mainstream feature films is compatible with Shklovsky’s idea: She has made the format’s customary subdivisions explicit.

Very often, you may need to stretch out a story situation to fit the time allotted. To some extent, folding several mini-plots into your big plot gives you the chance to extend the whole thing. In particular, often the plots don’t blend but actually block one another. In American Hustle, Rosalyn’s jealous-wife storyline serves to prolong the action around Irving and Richie’s scam, especially when she starts flirting with the casino magnates at the big dinner. Similarly, Richie’s escalating schemes to go after bigger crooks keeps thwarting Irving’s plan to mount simple scams that will let him and Sydney skate.

What to do when you lack material? We have some historical examples. In cinema, Griffith found several ways to fill out the one- and two-reel formats. Instead of simply showing characters coming into a scene, he filmed simple, mostly undramatic “goings and comings” that followed characters leaving one spot, traveling, and arriving at another spot. He also discovered that he could stretch out a situation by crosscutting two simultaneous actions.

An Aristotelian could say that Griffith discovered that crosscutting could generate suspense in rescue situations, but Shklovsky starts from sheer delay as an engineering principle. Why do the villains in such situations take such an ungodly time to accomplish their villainy? In 1923, Shklovsky recognized the emerging conventions of action cinema, still going strong today.

Attempted rape in a modern film is almost canonized. The victim is struggling, her friends are far away, the villain is pursuing the woman, “meanwhile,” etc. In my opinion, the choice of the crime in this instance is explained not so much by the desire to play on the spectator’s interest in eroticism as by the actual nature of the crime, which requires for its completion a certain amount of time. Instead of rape, take murder by pistol shot. Such an act is too indivisible. That is why cinematic villainy is usually perpetrated by a method that requires a large amount of time—drowning, for example, with the victim suspended upside down in a cellar and water pouring in. Sometimes the victim is bound hand and foot, then tossed on the railroad tracks, or else immured. Also effective is abduction in all its varieties. Only minor characters, not involved in the plot, are killed off immediately.

He might have added that the hero may be given a weak friend, whose death can be a little more protracted (and motivate the hero’s quest for revenge).

We tend to think of delay as padding, but actually narratives need it. Delay can be unmotivated, as digressions are. More often it’s motivated. In folk tales, why does the hero have two brothers? So that they can try and fail at the task that he will accomplish. (Hollywood’s rule of three may have its roots in folklore.) Stretching out the intervals between major plot points allows other things to be inserted—gags, character exposition, musical numbers, witty dialogue. Tarantino is very accomplished at dialogue-driven retardation. Call it the Royale-with-Cheese tactic.

It sounds strange to think of a novel’s descriptions of what characters eat and wear and drive as filler material. Ditto weather reports and portraits of neighborhoods. But Shklovsky suggests that in most cases that’s what these portions are, more or less motivated bits that flesh out the plot and connect the bits that the story-maker has brought on for this occasion. They can be further elaborated to create motifs and bind the work more firmly.

It seems even stranger that the same purposes of filling out the format and delaying the main events should be fulfilled by character traits. We tend to think of characters as modeled on living people—simpler, but with recognizable traits, habits, temperaments, and the like. For Shklovsky, a character can be minimal or maximal, depending on how much time or pages you have to fill. If your plot material is thin, you can thicken it by expanding your character, and at some point you have a psychological novel.

In some cases, by searching for material to expand the tale, the artist discovers new depths in his characters, as Shklovsky thinks Cervantes did with Don Quixote. The Don, initially a compilation of clichés drawn from chivalric romances, becomes richer as the first book proceeds. By the second book there’s a new self-consciousness about Quixote and Sancho, who are now famous to the other characters as heroes of the first book. You might think of The Godfather Part II or the sequels to Back to the Future when Shklovsky notes that the sequels to novels often change their structure radically, taking the original as a pretext for other explorations. The ill-remembered Book of Shadows: Blair Witch 2 (2000) and the more ingratiating Lion King 1 ½ (2004) use the Quixote device of building a sequel around characters who know the first installment.

Similarly, characterization serves to freshen up the familiar plot ingredients in American Hustle. Irving isn’t a slick con artist but rather a passable klutz who needs the social grace injected by Sydney. Richie isn’t your usual cop on a mission but a working-class guy burning with ambition, and this leads him to expand the scam to a level he can’t handle. Rosalyn is the slightly batty wife who’s expert in passive-aggressive combat. I suspect that what a lot of audiences enjoy about the film is the way several conventional characters are given vigorous detailing by the writing and the performances.

Happy ever after

The act of combining and fitting stories to a format demands that the storyteller find an ending. Shklovsky doesn’t have a lot of respect for endings. Given that making and motivating a plot are fairly arbitrary, the wrapup is likely to seem even more so. Shklovsky says that Thackeray wished he could order his servants to compose the endings of his novels.

Part of the problem is that while beginnings and middles bristle with surprises, resolutions are fairly routine. There’s the tragic ending, in which the hero dies. Another option is the ABA pattern, or “Here we go again.” In The Wolf of Wall Street, Jordan starts over, selling not stocks but the very idea of selling. Something similar seems to happen at the close of Into the Woods. The main action springs from people yearning for more than they have, given in the opening number, “I Wish.” After all the mishaps and deaths, the characters seem to settle for what happiness they have. Hence the bustling closing number, “Into the woods…and happy ever after.” But just as that song resolves and closure seems complete, Cinderella pipes up with “I wish….” Here we go again.

Then there is what Shklovsky calls the “incomplete” ending, the sort of open structure that doesn’t fully tell us how things work out. Chekhov and Maupassant are Shklovsky’s examples. In such instances, he points out, our cue for conclusion is often a description of the setting or the weather. In a way, these inconclusive endings acknowledge a fact of art: all endings are equally conventional, pieces of high artifice. None captures real life, which is absolutely endless in a way a text can’t be. Individuals die, but human life continues, and fate is essentially indefinite.

Shklovsky realizes, however, that readers favor the happy ending. Lovers are united, usually by marriage, or the adventurer returns safely from peril (the end of Jaws). American Hustle, being at bottom a romantic comedy, concludes with the main couple back together and successful in their art business. There’s also the formation of a secondary couple, Rosalyn and the mobster Pete. The pay-to-play mayor, who wants genuinely to help his city, gets mildly punished, while the real loser is the cop Richie. He becomes the expelled lover in the Ralph Bellamy tradition.

I think that Shklovsky would enjoy the film’s self-consciousness about its neat wrapup. American Hustle parodies the model of the incomplete ending. We never learn the outcome, or the point, of Stoddard’s childhood memory of ice-fishing. And the film’s final line, heard in Irving’s voice-over, ties his forged-painting scam to the overall dynamics of the plot: “The art of survival is a story that never ends.”

By tracing the activity of linking materials and filling the format, Shklovsky isn’t, I think, trying to describe every storyteller’s creative process. Many writers simply pour the stuff out. What I think he’s proposing are the principles behind the process. A practiced writer does all this intuitively. I once asked Elmore Leonard if he planned the very long dialogue scene that runs for several chapters in Get Shorty. He said, “It just came out that way.” But I notice that without that long section, the book would be severely out of balance—and too short. It’s a virtuoso cadenza, at once pure retardation and a package of motifs that point both forward and backward in the plot.

We’re now quite at home with films that intertwine storylines, restart storylines (Groundhog Day, The Butterfly Effect, Source Code), present branching and forking-path storylines (Run Lola Run, The Girl Who Leaped through Time), or simply set barely connected stories side by side (Chungking Express, Flirt, Nine Lives). So we should be ready to see more traditional plots as heavily camouflaged attempts at combining smaller stories. We should likewise be ready to see how stronger or lesser motivation governs all the options. Source Code relies on a science-fiction premise and a thriller deadline, while Groundhog Day motivates its replays and variations by setting its action on the one day that posits that the future will turn out either this way or that way.

For my part, I confess myself both an Aristotelian and a Shklovskian. I think that we ought to look for a plot’s structural unity at many levels. I think as well that those levels may incorporate the most wayward materials. The pieces are pulled into place and held there, sometimes precariously, by the scale of the format, their local purposes, and the motivational pressure of other components. Vincent Vega’s Royale-with-cheese exposition does hook up with the Big Cahuna burger we encounter later.

And both approaches provide useful critical tools. Seeing Jordan as a pretext for a dissection of his Wall Street world opens up certain aspects of the film that might not be apparent if we kept expecting him to follow a learning curve. By seeing how American Hustle braids together many standard plot patterns, we can explain how the film can juggle its situations with such speed and how we can look forward to seeing certain patterns fulfilled (or not). Studying narrative from either a holistic or a “montage” perspective can only enhance our appreciation of all the different kinds of stories we encounter.

To save you scrolling back up, here is another link to Shklovsky’s “Monument to a Scientific Error,” posted in the Essays section of this site.

This entry’s primary accounts of Shklovsky’s thinking on narrative are drawn from his essays “The Structure of Fiction” of 1925 and “The Making of Don Quixote” of 1921. Both are included in his landmark book Theory of Prose, originally published in 1925 and available in translation from the ever-vigilant Dalkey Archive. Shklovsky talks about the distinction between form and material in the early chapters of the 1923 book Literature and Cinematography, trans. Irene Masinovsky (Champaign: Dalkey Archive, 2008); my quotation about villainy is drawn from p. 60. Other references are from the 1981 Energy of Delusion: A Book on Plot, trans. Shushan Avagyan (Champaign: Dalkey Archive, 2007).

French Structuralism borrowed considerably from the OPOYAZ school. Roland Barthes launched his own version of Shklovsky’s retardation thesis in both his “Structural Analysis of Narratives” essay (the distinction between kernel actions and satellites) and his S/Z (the distinction between the proairetic code and the semic code). For his part, Shklovsky was skeptical about Structuralism, not least because of its vocabulary. “People today get carried away with terminology; there are so many terms that it’s impossible to learn them all, even if you’re a young person on vacation” (Energy of Delusion, 177).

My quotation from Sondheim about the construction of Into the Woods comes from Look, I Made a Hat: Collected Lyrics (1981-2011) with Attendant Comments, Amplifications, Dogmas, Harangues, Digressions, Anecdotes and Miscellany (Knopf, 2011), p. 57.

For more on how the split-roads motif of folklore persists in modern storytelling, see this earlier entry. I consider how embedded stories and framing situations can tax our memories in this entry. The multiple-drafts plot of Source Code is considered here, while various motivations for first-person video style are explored in these pieces on Cloverfield and the Paranormal Activity cycle.

Into the Woods cast, San Mateo High School production of May 2006.