HKIFF: Firebirds soar and MOTHER returns

Monday | April 7, 2014 open printable version

open printable version

Firebird Young Cinema Award winners and jury members, Hong Kong International Film Festival, 2014. For photos of all winners and jurors, go here.

DB here:

As my Hong Kong trip nears its end, I realize I’ve been too busy to blog properly. So when the wobbly net connections in my hotel permit, I’ll offer some quick entries on things I’ve seen and done.

Prizing movies

First, the big news. The festival hosts several annual awards. There are prizes from SIGNIS, the World Catholic Association for Communication, and FIPRESCI, the International Federation of Film Critics. The festival has established its own prizes as well: for best documentary, best short film, and for young filmmakers. The complete list of winners is here.

The jury for the Firebird Young Cinema Competition consisted of Bong Joon-ho, Karena Lam Ka Yan, Christopher Lambert, and me. We faced some hard choices, but we finally settled on three winners.

Special Mention went to Forma, by Ayumi Sakamoto. It’s a slow-burning thriller shot in mostly distant long takes and displaying a backward-looping time scheme that makes you rethink the first half. It also displays one virtue of video production: its crucial scene consists of a single shot, only apparently haphazardly composed, that lasts over 22 minutes!

We gave the Jury Prize to Tsuto Tetsuichiro’s Tale of Iya. It’s an extraordinarily ambitious film shot in 35mm Scope in a great variety of locales and weather conditions. It’s about the rigors of rural life, the need for ecological understanding, and a young woman’s growing awareness of her duties to her past. Some scenes recalled the great Japanese widescreen films of the 1950s and 1960s.

The top prize, the Firebird Award, went to Macondo, a very assured job of storytelling from Sudabeh Mortezai. The plot concerns Chechen refugees in Vienna struggling to get asylum status. At the film’s center is the remarkable performance of Ramasan Minkailov as a shrewd boy who has lost his father in the Chechin war. It’s a coming-of-age film, I suppose, but it also touches on issues of responsibility and loyalty without moralizing.

Serving on the jury was a treat for me, and I learned a lot from talking with my fellow jurors. Karena is famous for her roles in July Rhapsody and Inner Senses. More recently she has published Voyages, a remarkable book of Polaroid photographs. Christopher, as both actor and producer, has several new projects, including Electric Slide, coming to Tribeca. Joon-ho’s Snowpiercer will be released on 27 June in the US; after prolonged wrangling with Harvey Weinstein, this will be the director’s cut. The release will be limited, but it will pass to VOD thereafter.

Black and white is the new black

While finishing Snowpiercer, Bong took on a pretty intriguing side project. He told his cinematographer, Hong Kyung-pyo, that he’d always wanted to make a black-and-white film but that no producers would finance one nowadays. Hong suggested that they remake Mother (2009) in black-and-white. So during postproduction on the big film, they used spare days to redo the color data from the older one. It wasn’t simply a matter of hitting a button. They performed color correction shot by shot so as to control the exact degree of tonality and contrast.

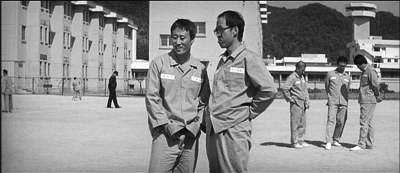

The result, already released on Blu-ray in South Korea and world-premiered at Mar del Plata, had its Asian premiere here in Hong Kong. It is exactly the same film, but without full color. Punning aside, it really does become more of a film noir–harsher, bleaker, and more somber.

The original film has a fairly muted palette, with lots of grays, beiges, soft blues, and earthy browns. In black and white you lose the nicely distinguished grayish-blues of a shot like this. (My monochrome frames are rough approximations derived from Photoshopping the color DVD; I don’t yet have the Blu-ray.)

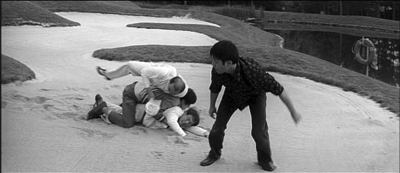

At the same time, the performances seem more highlighted in the new version. Bong noted that certain colors, such as the green on the golf course, were a little opulent in the original. In the new version they don’t overwhelm the characters, and the abstract elements of the composition become a bit more apparent.

Bong also observed that some viewers have said that the characters’ eyes—pure black—are more prominent in black and white. I had never thought about it, but in old films the actors’ gazes do seem more gripping. At times, the mother’s face becomes more haunted, and haunting.

Just as striking, a clue (I’d hate to call it a red herring) depends on a crimson smear on a golf club. Rendered in black-and-white it becomes even more ambivalent.

Bong said in the Q & A that the project satisfied an urge he discovered while watching Nosferatu at an archive screening without any music. “It was a very purified experience.” He wondered if he could go back to “a very pure state of film, like a salmon swimming upstream.” Yet the new version still harbors one visual surprise.

The monochroming of Mother seems to me a rewarding experiment; I look forward to comparing the two versions and seeing how each can suggest different sides of a scene or summon up different expressive qualities. At the moment, I prefer the black-and-white version, and Bong suggested that he was starting to do the same. After Nebraska and Mother, maybe filmmakers will rediscover what black-and-white can do—and producers and audiences will let them.

Forma (2013).